Abstract

Background

Although rates of total skin-sparing (nipple-sparing) mastectomies are increasing, the oncologic safety of this procedure has not been evaluated in invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC). ILC is the second most common type of breast cancer, and its diffuse growth pattern and high positive margin rates potentially increase the risk of poor outcomes from less extensive surgical resection.

Methods

We compared time to local recurrence and positive margin rates in a cohort of 300 patients with ILC undergoing either total skin-sparing mastectomy (TSSM), skin-sparing mastectomy, or simple mastectomy between the years 2000–2020. Data were obtained from a prospectively maintained institutional database and were analyzed by using univariate statistics, the log-rank test, and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

Of 300 cases, mastectomy type was TSSM in 119 (39.7%), skin-sparing mastectomy in 52 (17.3%), and simple mastectomy in 129 (43%). The rate of TSSM increased significantly with time (p < 0.001) and was associated with younger age at diagnosis (p = 0.0007). There was no difference in time to local recurrence on univariate and multivariate analysis, nor difference in positive margin rates by mastectomy type. Factors significantly associated with shorter local recurrence-free survival were higher tumor stage and tumor grade.

Conclusions

TSSM can be safely offered to patients with ILC, despite the diffuse growth pattern seen in this tumor type.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Preserving the skin of the nipple areolar complex during mastectomy is associated with improved quality of life compared with nonnipple-sparing techniques, and consequently rates of nipple-sparing mastectomy (NSM) have increased substantially.1,2,3 Despite higher utilization, controversy about oncologic safety persists.4,5 Several series have now reported on recurrence rates, nipple involvement, and positive margins in carefully selected patients undergoing NSM, and generally show these outcomes to be similar to those seen with other mastectomy techniques.6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15 However, no studies have investigated the safety of NSM in patients with invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC), the second most common type of breast cancer.

ILC lacks the adhesion protein E-cadherin and grows in a diffuse pattern with so-called “single file lines” of carcinoma cells.16 The combination of a diffuse growth pattern and the decreased sensitivity of imaging tools results in higher stages at presentation and increased rates of positive margins at surgical excision.17,18,19 Given these issues, patients with ILC may be at higher risk for worse oncologic outcomes from skin- and nipple-sparing techniques compared with nonskin-sparing mastectomies. Indeed, some published series that include patients with ILC appear to show a relatively higher rate of nipple involvement in these patients compared with other histologic subtypes, but small numbers of ILC patients make these findings inconclusive.10,20,21

Given the proclivity for margin involvement, and the lack of safety data for this subtype, we evaluated the oncologic outcomes in patients with ILC undergoing NSM (termed total skin-sparing mastectomy at our institution) compared with skin-sparing and nonskin-sparing mastectomies. Specifically, we evaluated time to local recurrence and positive margin rates across the three different mastectomy types in a cohort of patients with ILC.

Methods

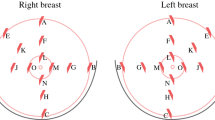

With approval from our Institutional Review Board, we queried a prospectively maintained institutional database and identified 700 cases of ILC. After excluding cases with de novo stage IV disease, less than 6 months of follow-up time, those undergoing breast conservation, and those treated before the year 2000, the study cohort consisted of 300 cases treated with mastectomy. Mastectomy type was defined as total skin-sparing mastectomy (TSSM) if the entire skin envelope, including the skin of the nipple areolar complex was preserved and immediate reconstruction performed, skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) if the nipple areolar complex skin was excised and immediate reconstruction performed, and simple mastectomy (SM) if the nipple areolar complex skin was excised, and no reconstruction was performed. Treatment era was analyzed in two equal time periods from the year 2000 until the year 2020 (2000–2010 and 2010–2020). TSSM has been utilized at our institution since 2001, with the majority performed through either periareolar or inframammary incisions. After early experience with higher skin flap loss in women with larger breasts, we developed institutional criteria for safely undergoing TSSM. As a general rule, good candidates for TSSM have C cup size or smaller and only up to grade 2 ptosis. For those with D cup or higher, or grade 3 ptosis, a reduction mammoplasty with subsequent TSSM 3-6 months later is offered if nipple preservation is desired. In some cases, acceptable results can be achieved in size D cup with grade 1 or less ptosis, whereas certain patients with grade 3 ptosis may never be good candidates. Additionally, gross tumor involvement of the nipple is a contraindication to TSSM at our institution, but otherwise no tumor size or location is uniformly excluded. Intraoperatively, the nipple areolar complex is sharply excised to the dermis, and retroareolar tissue is sent separately to pathology for histologic evaluation; frozen section is not routinely used. We collected margin status from clinical pathology reports and defined positive margins as ink on tumor per Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society of Radiation Oncology consensus guidelines.22

Data were analyzed in Stata 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) using the Chi squared test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. We used Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log-rank test to evaluate time to local recurrence by mastectomy type, and multivariable Cox proportional hazards models, including all variables significant on univariate analysis and standard clinicopathologic factors as predictors. The primary study endpoint was time to local recurrence between the three mastectomy types; the secondary endpoint was positive margin rate.

Results

In this cohort of 300 cases of ILC treated with mastectomy, average age was 56 years (range 29–89), and nearly half the cohort had stage I disease (47.7%, Table 1). Most tumors were grade 2 (67.2%) and of the estrogen receptor (ER)-positive, progesterone receptor (PR)-positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative subtype (76.4%). Median follow-up time in was 5.0 years, ranging from 0.53 to 18.7. Mastectomy type was TSSM in 119 (39.7%), SSM in 52 (17.3%), and SM in 129 (43%).

Mastectomy type was associated with patient age and era of treatment. Those receiving either TSSM or SSM were significantly younger than those receiving SM (average age 54, 55, and 59 years respectively, p = 0.0007). Earlier era of treatment was associated with significantly higher rates of SM and lower rates of TSSM (p < 0.001). Among the 130 mastectomies performed from 2000 to 2010, 62.3% were SM and 17.7% were TSSM; and among the 170 mastectomies performed from 2010 to 2020, 28.2% were SM and 56.5% were TSSM. There was no significant difference in tumor receptor subtype, grade, stage, receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of postmastectomy radiotherapy, receipt of adjuvant endocrine therapy, or presence of lymphovascular invasion across the three mastectomy types (Table 1).

There were a total of 17 local recurrence events in the study cohort, with rate of 4.2% in the TSSM group, 5.8% in the SSM group, and 7% in the SM group. On univariate analysis, there was no difference in time to local recurrence by mastectomy types (Fig. 1). Similarly, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model for local recurrence, including age, tumor stage, receptor subtype, tumor grade, presence of lymphovascular invasion, receipt of radiotherapy, receipt of endocrine therapy, receipt of chemotherapy, and era of treatment as predictors, there was no association between mastectomy type and time to local recurrence. In this model, higher stage disease and higher tumor grade were significantly associated with shorter time to local recurrence (Table 2). However, receiving endocrine therapy resulted in significantly improved local recurrence-free survival (hazard ratio [HR] 0.24, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.06-0.95, p = 0.042; Table 2).

Lastly, we evaluated the rate of positive surgical margins by mastectomy type. Of the 300 cases, margin data was available for 287 (95.7%). Overall, 34 patients (11.9%) had positive margins. The rate of positive margins did not differ significantly among the TSSM, SSM, and SM groups (12.7%, 18%, and 8.4% respectively, p = 0.197). This remained a nonsignificant difference when TSSM and SSM combined was compared with SM. Among the TSSM group, positive margin location was available in 9 of 15 cases (60%), and of those, the nipple areolar complex was involved in 3 (33%).

Discussion

In this study of 300 patients with ILC undergoing either TSSM, SSM, or SM, we found no difference in time to local recurrence or rate of positive surgical margins by mastectomy type. These data support the safety of TSSM with immediate reconstruction in patients with ILC, a tumor type known to have a diffuse growth pattern and high positive margin rates.

Despite the absence of prospective data and continued controversy in the literature regarding optimal patient selection for NSM, utilization of this procedure continues to increase, largely driven by improved patient quality of life, cosmetic results, and several published series suggesting good oncologic outcomes.2,23,24 Although many large series of outcomes in NSM exist, combining these data is challenging because of heterogeneity in patient selection, surgical technique, and outcomes reported.6,25,26 This heterogeneity make meta-analyses difficult and have led some to conclude that there is insufficient data to determine the safety of NSM in general.5 However, the preponderance of data together support acceptable oncologic outcomes from this surgical procedure.

Although histological subtype has been considered as a potential factor influencing outcomes after NSM, no published studies have specifically evaluated the outcomes for ILC.14,15,20 Interestingly, the literature contains subset analyses on small numbers of ILC patients that appear to show numerically worse results after NSM compared with invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). Brachtel et al. reported occult nipple involvement after NSM in 19% of patients with ILC versus 11% in those with IDC; while not statistically significant, this series had only 27 ILC patients, raising the question of sufficient power to identify such a difference. In an analysis of more than 600 therapeutic NSM by Tang et al., ILC was found in 18.6% of the 43 positive nipple margins, and IDC in 7%; although the total number of ILC patients was not reported, patients with IDC likely far outnumbered those with ILC given the prevalence of each histologic subtype. Whereas neither study specifically sought to evaluate the safety of NSM in ILC, findings such as these prompted us to investigate this issue. It is possible that larger studies comparing outcomes in ILC to IDC would in fact show a significantly higher positive margin rate in ILC. However, we chose instead to investigate the more clinically relevant question of how the type of mastectomy impacts oncologic outcomes within ILC, because this directly impacts surgical choice for patients with this disease. In addition to evaluating recurrence outcomes, we chose to include all positive margins, as opposed to nipple margins only, because differences in incision length and position between mastectomy types could potentially influence the ability to obtain clear margins at any location. Reassuringly, we found no difference in time to local recurrence or positive margins by mastectomy type. Our overall positive margin rate of 11.9% after mastectomy falls within the expected range, which is reported to be 9–14% for patients with invasive ductal carcinoma.27,28,29

Given the retrospective nature of this study, we do not know the reasons for selecting a particular surgical intervention, but it is possible that ILC patients with more aggressive features, such as lymphovascular invasion were recommended to undergo SM due to perceived recurrence risk. If patients with the most favorable tumors only were recommended for TSSM, this would limit our ability to compare the oncologic outcomes across mastectomy type. However, comparison of tumor stage, receptor subtype, and grade showed no difference across groups. Additionally, we used multivariate analysis to attempt to adjust for factors that differed, including age at diagnosis and era of treatment. Despite the limitations of this analysis, this study includes 119 ILC cases treated with TSSM, making it the largest series of ILC with surgical and recurrence outcomes data available.

Although ILC is known to have a diffuse growth pattern, which makes complete surgical excision more difficult, we found that performing TSSM is not associated with a higher risk of positive margins compared with other mastectomy types for this histologic subtype of breast cancer. Additionally, the oncologic outcome of time to local recurrence on both univariate and multivariate analysis did not differ by mastectomy type. This is the first series to report oncologic outcomes of TSSM in ILC and will hopefully contribute to improved options and outcomes for patients with this tumor type.

References

Wong SM, Chun YS, Sagara Y, Golshan M, Erdmann-Sager J. National patterns of breast reconstruction and nipple-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer, 2005–2015. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019;26:3194–203.

Romanoff A, Zabor EC, Stempel M, Sacchini V, Pusic A, Morrow M. A comparison of patient-reported outcomes after nipple-sparing mastectomy and conventional mastectomy with reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2909–16.

Bailey CR, Ogbuagu O, Baltodano PA, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes improve with nipple-sparing mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:219–26.

Agha RA, Al Omran Y, Wellstead G, et al. Systematic review of therapeutic nipple-sparing versus skin-sparing mastectomy. BJS Open. 2019;3:135–45.

Mota BS, Riera R, Ricci MD, et al. Nipple- and areola-sparing mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD008932.

Galimberti V, Morigi C, Bagnardi V, et al. Oncological outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy: a single-center experience of 1989 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:3849–57.

Sood S, Elder E, French J. Nipple-sparing mastectomy with implant reconstruction: the Westmead experience. ANZ J Surg. 2015;85:363–7.

Murphy BL, Hoskin TL, Boughey JC, et al. Outcomes and feasibility of nipple-sparing mastectomy for node-positive breast cancer Patients. Am J Surg. 2017;213:810–3.

Adam H, Bygdeson M, de Boniface J. The oncological safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy—a Swedish matched cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1209–15.

Brachtel EF, Rusby JE, Michaelson JS, et al. Occult nipple involvement in breast cancer: clinicopathologic findings in 316 consecutive mastectomy specimens. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4948–54.

D’Alonzo M, Martincich L, Biglia N, et al. Clinical and radiological predictors of nipple-areola complex involvement in breast cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:2311–8.

Margenthaler JA, Gan C, Yan Y, et al. Oncologic safety and outcomes in patients undergoing nipple-sparing mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;230:535–41.

Smith BL, Tang R, Rai U, et al. Oncologic safety of nipple-sparing mastectomy in women with breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;225:361–5.

Wu ZY, Kim HJ, Lee JW, et al. Breast cancer recurrence in the nipple-areola complex after nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction for invasive breast cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019.

Wang J, Xiao X, Wang J, et al. Predictors of nipple-areolar complex involvement by breast carcinoma: histopathologic analysis of 787 consecutive therapeutic mastectomy specimens. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1174–80.

Sledge GW, Chagpar A, Perou C. Collective wisdom: lobular carcinoma of the breast. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2016;35:18–21.

Fortunato L, Mascaro A, Poccia I, et al. Lobular breast cancer: same survival and local control compared with ductal cancer, but should both be treated the same way? Analysis of an institutional database over a 10-year period. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1107–14.

Winchester DJ, Chang HR, Graves TA, Menck HR, Bland KI, Winchester DP. A comparative analysis of lobular and ductal carcinoma of the breast: presentation, treatment, and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:416–22.

Johnson K, Sarma D, Hwang ES. Lobular breast cancer series: imaging. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:94.

Mallon P, Feron JG, Couturaud B, et al. The role of nipple-sparing mastectomy in breast cancer: a comprehensive review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:969–84.

Tang R, Coopey SB, Merrill AL, et al. Positive nipple margins in nipple-sparing mastectomies: rates, management, and oncologic safety. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:1149–55.

Houssami N, Macaskill P, Marinovich ML, Morrow M. The association of surgical margins and local recurrence in women with early-stage invasive breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:717–30.

Salgarello M, Visconti G, Barone-Adesi L. Nipple-sparing mastectomy with immediate implant reconstruction: cosmetic outcomes and technical refinements. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1460–71.

Wei CH, Scott AM, Price AN, et al. Psychosocial and sexual well-being following nipple-sparing mastectomy and reconstruction. Breast J. 2016;22:10–7.

Amara D, Peled AW, Wang F, Ewing CA, Alvarado M, Esserman LJ. Tumor involvement of the nipple in total skin-sparing mastectomy: strategies for management. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3803–8.

Haslinger ML, Sosin M, Bartholomew AJ, et al. Positive nipple margin after nipple-sparing mastectomy: an alternative and oncologically safe approach to preserving the nipple-areolar complex. Ann Surg Oncol. 2018;25:2303–7.

Yu J, Al Mushawah F, Taylor ME, et al. Compromised margins following mastectomy for stage I-III invasive breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2012;177:102–8.

Childs SK, Chen YH, Duggan MM, et al. Surgical margins and the risk of local-regional recurrence after mastectomy without radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84:1133–8.

Nguyen PL, Taghian AG, Katz, MS, et al. Breast cancer subtype approximated by estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER-2 is associated with local and distant recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26:2373–8.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Pamela Derish, MA, from the Department of Surgery at UCSF for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Laura Esserman—Dr. Esserman is an unpaid member of the board of directors of Quantum Leap Healthcare Collaborative, and received grant funding from QLHC for the I-SPY TRIAL; she is a member of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Medical Advisory Panel; she has a grant from Merck for an Investigator-initiated trial of DCIS.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Son, J.D., Piper, M., Hewitt, K. et al. Oncological Outcomes of Total Skin-Sparing Mastectomy for Invasive Lobular Carcinoma of the Breast: A 20-Year Institutional Experience. Ann Surg Oncol 28, 2555–2560 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09042-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09042-z