Abstract

Background

Small cell osteosarcoma is an extremely rare histopathological variant of conventional osteosarcoma. Due to nonspecific symptoms, most osteosarcomas of the jaws are misdiagnosed as periapical abscesses and mistreated by teeth extraction and drainage.

Case presentation

We report, to our knowledge, the seventh case of small cell osteosarcoma in gnathic sites affecting the mandible of an old female with history of a large painful swelling related to the right mandibular molar area for 2 months. Cone-beam computed tomography scan showed an osteolytic lesion related to the lower molar area with involvement of the inferior alveolar nerve. An incisional biopsy was taken, and after histopathological examination and immunohistochemical staining, a diagnosis of small cell osteosarcoma was reached. Hemi-mandibulectomy was performed by a maxillofacial surgeon. No clinical evidence for recurrence was noted until manuscript writing.

Conclusion

Accurate diagnosis is very important, and general practitioners should be aware of this entity considering that small cell osteosarcoma has a poor prognosis when compared to conventional osteosarcoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small cell osteosarcoma(SCOS) is a histopathological variant of conventional osteosarcoma (COS) and is extremely rare accounting for about 1 to 1.5% of all COSs [1]. It was first described in 1979 [2] and has a similar distribution as COS but is more frequently seen in the diaphysis of long bones (up to 15%). Also, it was reported to have a slightly worse prognosis than COS [3].

The clinical presentation of SCOS is not specific and is usually similar to COS, manifested most commonly as a swelling. The presence of pain, paresthesia, and ulcerations is less common symptoms [4]. The radiographical examination usually shows an osteolytic, sclerotic, or mixed radiolucent-radio-opaque lesion. Under the microscope, sheets of round cells producing an osteoid matrix can be seen.

Jaw bones are the fourth most common site for COS (particularly the mandible), accounting for approximately 6% of cases [5]. Dentists are usually the first to diagnose osteosarcomas of the jaws approximately in 45% of cases. This is due to the nonspecific symptoms, as two-thirds of the cases are misdiagnosed as periapical abscesses and mistreated by teeth extraction, drainage, and/or antibiotics [6].

Epidemiologically, SCOS are more commonly seen in the 3rd decade [7]. However, in this case report, we present the seventh case to our knowledge in gnathic sites affecting the mandible of an old female with a review of the existing literature.

Case report

A 62-year-old female Egyptian patient attended to the outpatient clinic of the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department, Cairo University in October 2022, complaining of a large painful swelling related to the right mandibular molar area (Fig. 1). The patient reported to have this swelling for 2 months. The swelling was initially diagnosed as a periapical abscess and was mistreated by teeth extractions, multiple incisions, and suturing by the general practitioner. The patient was in good physical health status, without any known health condition or any genetic disorder detected, also with no history of irradiation.

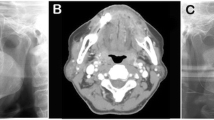

Intraoral examination revealed expansion of the buccal and lingual cortical plates related to the lower molars area with nonhealing mucosa due to the previous incisions. On palpation, a firm bony mass was felt. No fluctuation of mucosa or crackling was detected. There was no clinical evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy at the time of presentation. Cone-beam computed tomography scan showed a large radiolucency with indefinite margins related to the lower right molar area, with involvement of the inferior alveolar nerve (Fig. 2). PET scan did not reveal any evidence of distant metastasis.

An incisional biopsy was performed. Histopathological examination of hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections revealed sheets of round cells with an indistinct cellular outline. The cells had round-to-oval hyperchromatic nuclei, scanty cytoplasm, and distinct nuclear boundaries (Fig. 3). The malignant stroma had minimal osteoid deposition (Fig. 4).

The diffuse-positive nuclear immunohistochemical staining (IHC) of special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) marker confirmed the diagnosis of SCOS (Figs. 5 and 6). It was performed to exclude other small round cell tumors that occur in old age [8] such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma, small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma, and metastatic small cell carcinoma [9, 10].

Based on the combination of IHC evidence of osteoblastic differentiation of the tumor cells along with the presence of small round cells-producing bone matrix led to the final diagnosis of SCOS. Hemi-mandibulectomy with a 10-mm clear surgical margin was performed by maxillofacial surgeon. The reconstruction plate was used to join the condyle with the remaining part of mandible. After 6 months, the patient had undergone free fibula microvascular flap reconstruction. No adjuvant chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy was done. The histopathological examination and IHC staining results obtained from the received specimen were similar to the results of the earlier incisional biopsy. Follow-up of the patient showed no clinical evidence of recurrence until manuscript writing.

Discussion

In the recent 5th edition of the WHO classification of soft tissue and bone tumors, small cell osteosarcoma was merged under COS as a histopathologic variant [5]. Before that, it was considered as a stand-alone subtype of osteosarcoma for a long time. It is a rare variant, comprising about 1.5% of all osteosarcomas, first described by Sim et al. [11] as a distinct entity osteosarcoma with small cells simulating Ewing’s sarcoma.

The documented cases of SCCO were reported in several sites of the skeleton, such as pelvis and humerus [7]. However, to the extent of our knowledge, in gnathic sites (maxillary and mandibular jaws), there are only 6 reported cases in the English language literature (Table 1), whereas 5 cases were reported in the mandible and only one in the maxilla. We report the seventh case of gnathic sites affecting the mandible of a 62-year-old female. The reported median age of diagnosis was 26.7 affecting both sexes almost equally [6, 12,13,14,15,16].

To date, there is no specific molecular genetic alteration for SCOS. However, in some documented cases, there were many patients who had either Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 (EWSR1) or BCOR that encodes the BCL-6 corepressor protein rearrangements reported [17,18,19,20]. Interestingly, Noguera et al. reported one case of translocation (11; 22) [21]. In addition, by genomic sequencing of the breakpoint between EWSR1 and CREB3L1, Debelenko et al. confirmed the chimeric fusion gene transcripts [22].

All the documented cases of SCOS shared the same histopathological criteria which are sheets of small round cells with indistinct cellular outlines separated by dense fibrous tissue. The tumor cells usually have scant eosinophilic cytoplasm with nuclei that are generally small to medium and round to oval in shape. The presence of osteoid in the stroma is considered a cornerstone for SCOS differentiation from other small round cell tumors. In our case, the diagnosis was challenging because the malignant stroma had minimal osteoid deposition arranged in a lacelike fashion.

SCOS stain positively to considerable number of IHC markers such as CD99, vimentin, osteocalcin, osteonectin, and cytokeratin [5, 16, 23]. These markers also stain several round cell tumors. The special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) is an important transcription factor for osteoblastogenesis and is considered a highly sensitive marker for osteoblast lineage differentiation. In our case, it was used to rule out the other undifferentiated round cell sarcomas such as Ewing and the so-called Ewing-like sarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma (these previous tumors usually occur in the pediatric age) [7, 18]. Moreover, the positive staining helped us to exclude other round cell tumors that share various degrees of similarity with SCOS like non-Hodgkin lymphoma, metastatic small cell melanoma, poorly differentiated synovial sarcoma, small cell carcinoma, neuroblastoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma [7].

Surgical resection with clear margins was done for the patient, and this is considered the treatment of choice [5]. Aggressive lesions with local invasion needed adjuvant therapy like chemotherapy and radiotherapy [15]. Follow-up of our patient did not show any evidence of recurrence until writing this manuscript. It is worth mentioning that, in three of the documented cases, the recurrence was not recorded [12, 14, 16], two of the documented cases showed no evidence of recurrence [13, 23], and one case showed local recurrence in the orbit after 1 year and a half [15]. The use of SATB2 could be a possible strength point in this study, as it is considered a highly sensitive marker for osteoblast lineage differentiation. However, the absence of diagnostic molecular genetic testing and short follow-up period could be the limitation.

Conclusion

In conclusion, SCOS is an extremely rare variant histopathological of COS of the head and neck area and has aggressive behavior with local invasion leading to difficulty in controlling the lesion and ultimately a high mortality rate. The takeaway lesson is that general practitioners must be aware of this entity that has no specific symptoms to avoid misdiagnosis and mistreatment as an abscess. The special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2) IHC marker is a helpful tool to reach a proper diagnosis, especially when osteoid production is minimal to differentiate SCOS from other histopathological mimickers’ tumors. The accurate diagnosis is very important to achieve an effective curative regimen that will improve patient survival, considering that SCOS has a poor prognosis when compared to COS (2).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COS:

-

Conventional osteosarcoma

- SCOS:

-

Small-cell osteosarcoma

- IHC:

-

Immunohistochemical

- SATB2:

-

Special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2

References

Nakajima H, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma of bone. Review of 72 cases. Cancer. 1997;79(11):2095–106.

Sim FH, et al. Osteosarcoma with small cells simulating Ewing’s tumor. 1979;61(2):207-215.

Ricotta F, et al. Osteosarcoma of the jaws: a literature review. Curr Med Imaging. 2021;17(2):225–35.

ElKordy MA, et al. Osteosarcoma of the jaw: challenges in the diagnosis and treatment. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2018;30(1):7–11.

WHO Classifcation of Tumours Editorial Board. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2022. (WHO classifcation of tumours series, 5th ed.; vol.9).

Kuo C, Kent PM. Young adult with osteosarcoma of the mandible and the challenge in management: review of the pediatric and adult literatures. J Pediatric Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(1):21–7.

Zhong J, et al. Clarifying prognostic factors of small cell osteosarcoma: a pooled analysis of 20 cases and the literature. J Bone Oncol. 2020;24: 100305.

Domanski HA. The small round cell sarcomas complexities and desmoplastic presentation. Acta Cytol. 2022;66(4):279–94.

Wei S, Siegal GP. Small round cell tumors of soft tissue and bone. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;146(1):47–59.

Zhuvithsii Z, et al. Histopathological study of round cell tumors of the head and neck region in a tertiary care hospital. J Pathol Nepal. 2022;12:1923–8.

Sim FH, et al. Osteosarcoma with small cells simulating Ewing’s tumor. JBJS. 1979;61(2):207–15.

Giangaspero F, et al. Small-cell osteosarcoma of the mandible Case report. Appl Pathol. 1984;2(1):28–31.

Harazono Y, et al. A case of highly suspected small cell osteosarcoma in the mandible. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2015;27(1):38–40.

Kim Y, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma similar to Ewing’s sarcoma in histologic findings and MIC2 expression: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 1999;33((3)):204–209.

Selvakumar AS, Rajalakshmi V. Small cell osteosarcoma of the maxilla. Indian J Pathol Oncol. 2017;4((4)):655–657.

Sethi AT, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma of mandible: a rare case report and review of literature. J Clin Exp Dent. 2010;2:96-99.

Kilpatrick SE, Reith JD, Rubin B. Ewing sarcoma and the history of similar and possibly related small round cell tumors: from whence have we come and where are we going? Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25(5):314–26.

Righi A, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular analysis of 36 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39(5):691–699.

Machado I, et al. Histopathological characterization of small cell osteosarcoma with immunohistochemistry and molecular genetic support. A study of 10 cases. Histopathology. 2010;57(1):162–167.

Dragoescu E, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma with Ewing sarcoma breakpoint region 1 gene rearrangement detected by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2013;17(4):377–82.

Noguera R, Navarro S, Triche TJ. Translocation (11;22) in small cell osteosarcoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1990;45(1):121–4.

Debelenko LV, et al. A novel EWSR1-CREB3L1 fusion transcript in a case of small cell osteosarcoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2011;50(12):1054–1062.

Uma K, et al. Small cell osteosarcoma of the mandible: case report and review of its diagnostic aspects. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15(3):330–4.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Faculty of Dentistry, Cairo University.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception, HA, SH, and HA. Design of the work, HA, SH, and HA. Investigation, HA. Formal analysis, HA. Supervision and visualization, HA and SH. Drafted the manuscript and data curation, HA. Critical revision of the manuscript, HA and SH. Final approval, all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This work was approved by the Research Ethical Committee at the Faculty of Dentistry, Cairo University, done in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration, and written informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor in chief of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Amer, H.W., Algadi, H.H. & Hamza, S.A. Mandibular small cell osteosarcoma: a case report and review of literature. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 35, 30 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-023-00191-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s43046-023-00191-2