Abstract

The paper proposes a novel classification and analysis of the V-DE construction in Mandarin Chinese. On this proposal, the V-DE construction is divided into two types, predicative and non-predicative. The predicative type can be further divided into entity-predicative V-DE constructions and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions. With respect to the analysis of the V-DE construction, the paper identifies four different structures. It points out that the de-part (i.e. the part after and marked by 得 -de) in most V-DE constructions is a clause with or without an overt subject. Moreover, with respect to the cases where the de-part has an overt NP that can be interpreted as the Patient argument of the verb before -de and at the same time is semantically compatible with the VP or AP in the de-part, the paper proposes that the overt NP in such cases is syntactically the subject of the de-clause and syntactically is not the direct object of V-DE or the verb before -de. Finally, when the de-part of an entity-predicative V-DE construction has an overt NP between -de and the predicate of the de-clause, the AP or VP of the de-part generally needs to be predicated of the overt NP in the de-part. This constraint, however, can be occasionally relaxed to allow for a pragmatically-inducted interpretation when both of the following conditions are met: (i) the de-part is a well-formed clause in both form and meaning and (ii) the pragmatically-induced interpretation is pragmatically plausible.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The V-DE construction in Mandarin Chinese, as illustrated in 1–4, has been given various names and classifications.Footnote 1

-

(1)

张三跑得很快。

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__hen__kuai.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__ very__fast

-

Zhangsan runs very fast.

-

-

(2)

张三疼得很厉害。

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__hen__lihai.

-

Zhangsan__ache-de__ very__severe

-

Zhangsan has/had a terrible pain.

-

-

(3)

张三坐得背都疼了。

-

Zhangsan__zuo-de__bei__dou__teng-le.

-

Zhangsan__sit-de__ back__ emphasis__ hurt- perf

-

Zhangsan sat to the extent that his back hurt.

-

-

(4)

那个怪物吓得张三跳了起来。

-

Na-ge__guaiwu__xia-de__Zhangsan__tiao-le__qilai.

-

that-cl__monster__scare-de__ Zhangsan__jump- perf__ up

-

That monster scared Zhangsan and caused him to jump up.

-

For example, Li and Thompson (1981) call the V-DE construction the “complex stative construction” and divide the construction into two types according to whether the de-part, the part after and marked by 得 -de, expresses “manner” (e.g. 1) or “extent” (e.g. 3). This classification or distinction is also adopted by Shi (1990). For another example, Zhu 朱德熙 (1982) and Wang et al. 王理嘉等 (2004) name the de-part 状态补语 zhuangtai buyu ‘stative complements’ and 程度补语 chengdu buyu ‘degree complements’, with the latter covering both degree and state. Moreover, as far as the “complement” introduced by -de is concerned, Wang and Shi 王邱丕, 施建基 (1990) make a distinction between 程度补语 chengdu buyu ‘degree complements’ and 情状补语 qingzhuang buyu ‘situational stative complements’ and Liu et al. 刘月华等 (2001) distinguish between 程度补语 chengdu buyu ‘degree complements’ and 情态补语 qingtai buyu ‘situational stative complements’.Footnote 2

Following Huang et al. (2009), I simply call the construction illustrated by 1–4 the “V-DE construction”, in which “V” covers both verbs and adjectives. Importantly, −de in this construction, as a suffix, and the V right before it do not form a new lexical item (see below). The main purposes of this paper are (i) to review classifications and analyses of the V-DE construction by Li and Thompson (1981), Li (1990), and Huang et al. (2009) and point out their problems and (ii) to offer an alternative classification and analysis and further discuss previous proposals made with respect to this construction. In what follows, I will first discuss the three previous proposals and then offer my alternative classification and analysis.

2 Literature review

2.1 Li and Thompson’s (1981) classification and analysis

As mentioned above, Li and Thompson (1981) use the term “complex stative construction” to refer to the V-DE construction. According to them, the V-DE construction has the structure in 5. That is, the de-part may be a clause or a “verb phrase”, which actually includes adjectival phrases.

-

(5)

Li and Thompson (1981: 623)

Moreover, according to Li and Thompson, the part before -de and the de-part may have two different kinds of relationship: manner and extent. The manner interpretation is available when the stative “verb phrase” is an adjective used to describe “the manner in which the event described by the first clause of the complex stative construction occurs” (Li and Thompson 1981: 623). The following are three examples:

-

(6)

Li and Thompson (1981: 623–624, tones omitted)

-

a.

李四来得真巧。

-

Lisi__lai-de__zhen__qiao.

-

Lisi__come-de__real__coincidental

-

It was really a coincidence that Lisi came.

-

-

b.

我们睡得很好。

-

Women__shui-de__hen__hao.

-

we__sleep-de__very__good

-

We slept very well.

-

-

c.

她/他走得非常早。

-

Ta__zou-de__feichang__zao.Footnote 3

-

3sg__leave-de__extremely__early

-

S/He left really early.

-

-

a.

As for the extent interpretation, it becomes available when “the event in the first clause is done to such an extent” that the “result is the state” expressed by the part after -de (Li and Thompson 1981: 626). This is illustrated by the three examples in 7 below. Although Li and Thompson do not give an explicit structure for each example, it is clear from their discussion that they view 7a and 7b as involving a “stative verb phrase” and regard 7c as involving a stative clause.

-

(7)

Li and Thompson (1981: 626, tones omitted)

-

a.

她/他笑得站不起来。

-

Ta__xiao-de__zhan-bu-qi-lai.

-

3sg__laugh-de__stand-can’t-rise-come

-

S/He laughed so much that s/he couldn’t stand up.

-

-

b.

她/他教得累了。

-

Ta__jiao-de__lei__le.

-

3sg__teach-de__tired__crs

-

S/He taught so much that s/he is tired.

-

-

c.

我哭得眼睛都红了。

-

Wo__ku-de__yanjing__dou__hong__le.

-

I__cry-de__eye__all__red__crs

-

I cried so much that my eyes got all red.

-

-

a.

Finally, according to Li and Thompson (1981), a V-DE construction can be ambiguous and allow both a manner and an extent interpretation, as shown in 8. Recall that the manner inference, on Li and Thompson’s view, obtains only when the part after -de is an adjective. As a result, it seems that ambiguity can possibly arise only when the de-part has an overt adjective alone.

-

(8)

Li and Thompson (1981: 627–628, tones omitted)

-

a.

我们吃得很开心。

-

Women__chi-de__hen__kaixin.

-

we__eat-de__very__happy

-

(i) We ate very happily.

-

(ii) We ate to the point of being very happy.

-

-

b.

她/他哭得很伤心。

-

Ta__ku-de__hen__shang-xin.

-

3sg__cry-de__very__hurt-heart

-

(i) S/He cried very sadly.

-

(ii) S/He cried to the point of being very sad.

-

There are several problems with Li and Thompson’s classification and analysis of the V-DE construction. First, the structure in 5 fails to cover cases like 9, which involves an adverb phrase after -de (see further discussion below).

-

(9)

张三的衣服多得很。

-

Zhangsan-de__yifu__duo-de__hen.

-

Zhangsan-gen__clothes__many-de__very

-

Zhangsan has a lot of clothes.

-

Second, Li and Thompson’s use of “manner” and “manner inferred” to describe the relationship between the part before -de and the one after -de in examples like 6 is not accurate. This is due to the fact that ‘coincidental’ in 6a is not used to describe the manner of Lisi’s coming. Similarly, ‘very good’ in 6b is not used to describe the manner of our sleeping and ‘really early’ in 6c is not used to describe the manner of his or her leaving. What the de-part does in 6 is offer an evaluative or assertive comment about the eventualityFootnote 4 expressed by the verb immediately before de, which, according to Li and Thompson, is presupposed.Footnote 5 For example, ‘very good’ in 6b is about how the sleeping was, not about the manner or way in which the sleeping action took place. Moreover, a true manner phrase in Mandarin, which specifies the manner or way in which an action takes place, occurs before the verb or adjective it modifies, as shown in 10. For instance, 快速 kuaisu ‘quickly’, when used to specify the manner of the running action in 10a, must occur before the verb 跑 pao ‘to run’. Therefore, there are both semantic and distributional differences between true manner phrases and comment phrases or clauses marked by -de in the case of the V-DE constructions. In this respect, it is worth pointing out that Li and Thompson (1981: 625) themselves actually mention that “manner adverb sentences” like 10 “always refer to an action” and V-DE constructions like 6 “always refer to a state of affairs” (emphasis original).

-

(10) a.

他快速地向我跑过来。

-

Ta__kuaisu__de__xiang__wo__pao__guolai.

-

he__quickly__de__toward__I__run__over

-

He is running over to me quickly.

-

-

b.

张三兴奋地跳上了舞台。

-

Zhangsan__xingfen__de__tiao-shang-le__wutai.

-

Zhangsan__excitedly__de__jump-onto-perf__stage

-

Zhangsan excitedly jumped onto the stage.

-

Third, there is evidence that the de-part is a clause instead of a phrase when it has an adjectival phrase (e.g. 6 and 7b) or verb phrase (e.g. 7a) but does not have an overt noun phrase. The following are two more such examples.

-

(11)

张三跑得很快。(=1)

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__hen__kuai.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__very__fast

-

Zhangsan runs very fast.

-

-

(12)

张三昨晚睡得很香。

-

Zhangsan__zuowan__shui-de__hen__xiang.

-

Zhangsan__last.night__sleep-de__very__sound

-

Zhangsan had a sound sleep last night.

-

I argue that the de-part in sentences like 11–12 is in fact a clause with a null subject because the overt constituent in these de-parts is not only predicative but also functions as the predicate of a clause.Footnote 6 This is supported by the following facts. First, 快 kuai ‘fast’ in 11, for example, is an adjective, not an adverb and there is evidence for it. The determination of the category of kuai in 11 is very important in this case because the same form may have both an adjectival and an adverbial use in Chinese. However, only the use of kuai as an adjective is predicative. As a result, to determine that kuai in 11 is predicative, we need to determine that it is an adjective. Crucially, there is evidence that kuai in 11 is indeed an adjective. Although the same form in Chinese may have both an adjectival and an adverbial use, the two uses are different and can be distinguished between each other with the following fact. When kuai ‘fast’ is used as an adjectival predicate (kuai 1 ), it needs to be modified in a non-contrastive context as far as declarative sentences are concerned. For a bare adjectival predicate to be meaningful, it has to be interpreted as forming a contrast, regardless of whether the other entity in contrast is overtly expressed or not. In the case of 13b below, it is grammatical only in a contrastive context. In a non-contrastive context, a form like 13a that involves the use of a degree modifier before kuai needs to be employed. However, when kuai ‘fast’ is used as an adverb (kuai 2 ), which cannot be predicative, the bare form cannot be used even in a contrastive context, as shown in 14a (cf. 14b). Interestingly, the use of kuai in 11 corresponds to the use of kuai 1 , not kuai 2 , as shown in 15, in which the bare form of kuai can be used and the whole sentence is grammatical only in a contrastive context. This strongly suggests that kuai in 11 is adjectival and predicative.Footnote 7

-

(13)

a. 现在火车很快。

-

Xianzai__huoche__hen__kuai.

-

now__train__very__fast

-

Trains are fast nowadays.

-

b.

火车快。(OK in a contrastive context; bad in a non-contrastive context)

-

Huoche__kuai.

-

train__fast

-

The train is fast.

-

-

-

(14)

a. *他快地向我跑过来。(Bad even in a contrastive context)

-

*Ta__kuai__de__xiang__wo__pao __guolai.

-

he__quickly__DE__toward__I__run__over

-

Intended: He was running over to me quickly.

-

b.

他很快地向我跑过来。

-

Ta__hen__kuai__de__xiang__wo__pao__guolai.

-

he__very__quickly__de__toward__I__run__over

-

He was running over to me quickly.

-

-

-

(15)

张三跑得快。(Grammatical only in a contrastive context)Footnote 8

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__kuai.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__fast.

-

ZHANGSAN runs fast. OR Zhangsan RUNS fast.

-

Second and more important, there is evidence that kuai in 11 functions as the predicate of a clause. For one thing, kuai can occur in the V-not-V form, as shown in 16 (cf. 17).

-

(16)

张三跑得快不快?

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__kuai-bu-kuai?

-

Zhangsan__run-de__fast-not-fast

-

Does Zhangsan run fast?

-

-

(17)

火车快不快?

-

Huoche__kuai-bu-kuai?

-

train__fast-not-fast

-

Is the train fast?

-

For another, kuai can also be suffixed with the aspect marker -le, as shown in 18 (cf. 19; see also 4 for the use of -le in the de-part).Footnote 9 This unambiguously shows that the part marked by de is a clause.

-

(18)

张三跑得比以前快了一点儿。

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__bi__yiqian__kuai-le__yidianr.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__than__before__fast-perf__a.little

-

Zhangsan (now) runs a bit faster than before.

-

-

(19)

火车比以前快了一点儿。

-

Huoche__bi__yiqian__kuai-le__yidianr.

-

train__than__before__fast-perf__a.little

-

The train (now) is a bit faster than before.

-

Moreover, kuai can be negated in the V-DE construction, as shown in 20 (cf. 21).Footnote 10

-

(20)

张三跑得不快。

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__bu__kuai.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__not__fast

-

Zhangsan does not run fast.

-

-

(21)

火车不快。

-

Huoche__bu__kuai.

-

train__not__fast

-

The train is not fast.

-

Taking into account all of the facts discussed above, I propose that V-DE constructions like 11–12 should be analyzed as having the structure in 22, in which the null element refers back to the eventuality expressed by the verb before -de. In the case of 11, for example, the null element refers to the running by Zhangsan.Footnote 11

-

(22)

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø AP ]]] (Ø=null element)

When the de-part only has an overt verb phrase (see 7a above and 23a below), it in fact involves a clause containing this verb phrase as well. For instance, 叫 jiao ‘yell, shout’, as a verb in 23a, is undoubtedly the predicate of a clause, as evidenced by the fact that jiao, for example, can be used in the V-not-V form (see 23b) and can be followed by the perfective marker -le (see 23c). As a result, V-DE constructions like 23a and 7a should have the structure in 24.

-

(23) a.

张三疼得直叫。

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__zhi__jiao.

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__continuously__yell

-

Zhangsan hurt so much that he yelled and yelled.

-

b.

张三疼得叫没叫?

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__jiao-mei-jiao?

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__yell-not-yell

-

Did Zhangsan yell due to his pain?

-

-

c.

张三疼得叫了又叫。

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__jiao-le__you__jiao.

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__yell-perf__again__yell

-

Zhangsan hurt so much that he yelled over and over.

-

-

-

(24)

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø VP ]]] (Ø=null element)

When 22 and 24 are taken together, it can be concluded that in fact all the V-DE constructions discussed by Li and Thompson involve a clause marked by -de.

2.2 Li’s (1990) classification and analysis

Li (1990) discusses two types of V-DE constructions. According to her, the first type, as illustrated in 25, involves a “descriptive expression”. As for the second type, it involves a “resultative expression”, as shown in 26.

-

(25)

他跑得很快。(Li 1990: 43)

-

Ta__pao-de__[hen__kuai].

-

he__run-de__very__fast

-

He ran fast.

-

-

(26)

他跑得很累。(ibid.)

-

Ta__pao-de__[hen__lei].

-

he__run-de__very__tired

-

He ran till very tired.

-

Li (1990) does not define “descriptive expression” and “resultative expression”, but it seems that her first type corresponds to Li and Thompson’s examples where, according to Li and Thompson, a “manner” interpretation arises. As for Li’s second type, it can be said to correspond to Li and Thompson’s V-DE constructions where “extent” can be inferred.

According to Li (1990: 44), descriptive and resultative expressions are of “different syntactic categories”. The former are APs and the latter are clauses, and they have different structures, as shown in 27. In this respect, Li (1990) and Li and Thompson (1981) assign different structures to a resultative V-DE construction whose de-part contains an overt adjective or verb phrase alone. This de-part is a clause to Li (1990), but a phrase to Li and Thompson (1981).

-

(27) a.

[S NP X [VP V de AP]] (descriptive) (Li 1990: 48)

-

b.

[NP1 [X [V1-de [(NP2) VP2]]]] (resultative) (Li 1990: 58)

Li (1990) claims that the categorical contrast between descriptive and resultative expressions is supported by the fact that, while resultative expressions allow an overt noun phrase, descriptive expressions do not. This is shown in 28, in which 28a involves a descriptive expression and 28b a resultative expression.

-

(28)

Li (1990: 43)

-

a.

*他跑得腿很快。

-

*Ta__pao-de__tui__hen__kuai.

-

he__run-de__leg__very__fast

-

-

b.

他跑得人很累。

-

Ta__pao-de__ren__hen__lei.

-

he__run-de__man__very__tired

-

He got tired from running.

-

-

a.

Li’s (1990) classification and analysis of the V-DE construction have the following shortcomings. First, the use of “descriptive” cannot really distinguish between the two types of V-DE constructions discussed by her, given the fact that a resultative expression of the V-DE construction is also a description of the result that arises from the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de. Second, Like Li and Thompson’s, Li’s description and analysis of the V-DE construction is incomplete in the sense that it fails to cover examples like 9 above, which involves an adverb phrase. Third, as can be concluded from the previous discussion of Li and Thompson’s analysis of V-DE constructions whose de-part has an overt adjectival phrase alone, Li’s (1990) “descriptive” de-parts in fact involve a clause.

2.3 Huang et al.’s (2009) classification and analysis of the V-DE construction

With respect to the V-DE construction, Huang et al. (2009) make a distinction between “manner V-DE” (see 29) and “resultative V-DE” (see 30) (cf. Li and Thompson’s (1981) “manner” interpretation and “extent” interpretation of the V-DE construction).

-

(29)

你唱得特别好听。(Huang et al. 2009: 87)

-

Ni__chang-de__tebie__haoting.

-

you__sing-de__especially__pleasant.to.listen.to

-

You sing especially well.

-

-

(30)

他气得我不想写信了。(Huang et al. 2009: 84)

-

Ta__qi-de__wo__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__annoy-de__me__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

He annoyed me so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

Huang et al. analyze the manner V-DE illustrated in 29 as having a structure in 31.

-

-

(31)

Ni chang [XP de tebie haoting] (cf. Huang et al. 2009: 89)

According to them, this analysis is motivated by “a conflict of requirements” due to the following two factors: (i) the “manner” de needs to be suffixed to a verb or adjective; (ii) the modification relation established between the verb or adjective and the “manner” phrase marked by -de does not allow the “manner” phrase to occur after that verb or adjective because in the case of verbal compounds the modifying part always precedes the modified element, as shown in 32. Moreover, according to Huang et al. (2009: 88), “[the] only way to resolve the conflict is for de and the verb to be separate constituents structurally but pronounced as a unit”. They further comment that, since de and the verb or adjective “do not form a structural unit in the sense of lexical word-formation, the compounding pattern shown in [32] becomes irrelevant” (ibid.; emphasis added). In this regard, Huang et al. seem to assume that, if de and the verb or adjective do form a structural unit, de and the part after de should follow the pattern of 32 and should be used before the verb or adjective which they “modify”.

-

(32)

飞快, 静坐, 生吃, 重视, 怒吼 (Huang et al. 2009: 88)

-

fei-kuai jing-zuo, sheng-chi, zhong-shi, nu-hou

-

fly-fast quiet-sit raw-eat heavy-view angry-shout

-

very fast sit quietly eat raw take seriously shout angrily

-

As for the resultative V-DE exemplified by 30, Huang et al. (2009) analyze the sentence as having the structure in 33.

-

-

(33)

He annoy-de me [S Pro not want write letter] (Huang et al. 2009: 86)

-

According to Huang et al., 我 wo ‘I, me’ in 30 should be analyzed as the direct object of 气 qi ‘to annoy’, as seen in the structure in 33.Footnote 12 This analysis is proposed on the basis of their observation that the interjection 呀 ya can be inserted between a verb and its clausal object (e.g. 34), but not between a verb and its postverbal NP object (e.g. 35a) (see also Li 1998 for the use of the same diagnostic). Moreover, as shown in 35b, ya, on the other hand, can be used after the verb and its postverbal NP object.

-

-

(34)

他说呀, 朋友去投奔亲戚了。(Huang et al. 2009: 85)

-

Ta__shuo__ya,__[S pengyou__qu__touben__qinqi__le].

-

he__tell__ya__friend__go__seek.refuge.with__relative__sfp

-

*He told, um, his friend to go to the relatives for shelter.

-

-

(35)

Huang et al. 2009: 85

-

a.

*他告诉呀, 朋友去投奔亲戚。

-

*Ta__gaosu__ya,__pengyou__[S Pro__qu__touben__qinqi].

-

he__tell__ya__friend__Pro__go__seek.refuge.with__relative

-

He said, um, that his friend went to the relatives for shelter.

-

-

b.

他告诉朋友呀, 去投奔亲戚。

-

Ta__gaosu__pengyou__ya,__[S Pro__qu__touben__qinqi].

-

he__tell__friend__ya__Pro__go__seek.refuge.with__relative

-

He told his friend, um, to go to the relatives for shelter.

-

-

a.

Given this and given the fact that ya can be added immediately after wo in 30 but not immediately before it and maintain the same interpretation (see 36), Huang et al. propose to assign the structure in 33 to 30. Crucially, according to Huang et al.’s analysis in 33, wo in 30 is not the overt subject of the clause after de, but the direct object of the main verb qi. Moreover, with respect to the resultative V-DE construction it should be pointed out that Huang et al. analyze it as involving a structural constituent composed of the V and de, a constituent that is analogous to a Mandarin resultative verb compound (RVC) like 洗干净 xi-ganjing ‘wash-clean’.

-

(36)

Huang et al. 2009: 85

-

a.

他气得我呀, 不想写信了。

-

Ta__qi-de__wo__ya,__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__annoy-de__me__ya__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

He annoyed me so much, um, that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

b.

#他气得呀, 我不想写信了。

-

#Ta__qi-de__ya,__wo__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__annoy-de__ya__me__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

#He was so annoyed that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

a.

There are several problems with Huang et al.’s classification and analysis of the V-DE construction. First, as discussed with respect to Li and Thompson’s (1981) “manner” interpretation, the part after -de in the so-called “manner V-DE” in fact involves an evaluative comment about the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective immediately before de. “Manner” in this case is a misnomer because on the one hand manner specifies the way in which an action takes place and on the other hand the de-part in 29, for example, does not specify the way of the action, but rather offers an evaluative comment about the singing action. Specifically, the de-part in 29 is about how the singing is, not about the manner or way in which the action takes place. In addition, as discussed earlier, a true manner phrase in Mandarin, which specifies the manner or way in which an action takes place, occurs before the verb or adjective it modifies.

Second, there is no good reason for Huang et al. to analyze the V and de in 29 and the ones in 30 in different ways. For one thing, semantically the de in 29–30 originally meant ‘to obtain’, from which the meaning of ‘to achieve’ was derived (see Huang 1988: 275; Sun 1996: 108, 112; Wang 王力 1980 [1958]: 299–302; Yang 杨平 1989: 133, 1990: 56). This achieve-de in both 29 and 30 occurs after the eventuality that leads to the achieved effect, quality, degree, result, or state, just as RVCs in Mandarin have the order of the result predicate appearing after the causing predicate (e.g. 拧干 ning-gan ‘wring-dry’, in which the wringing action causes something to become dry). For another, the current status of de is an inflectional suffix (Dai 1990), and -de is attached to the preceding verb in both 29 and 30.Footnote 13 As the phrase marked by -de in 29 serves as a comment on the eventuality denoted by the verb and not as a true manner expression (see above), there is no good reason for Huang et al. to expect that phrase to behave like a manner phrase. Still more, the data in 32 are irrelevant to the ordering of the verb, −de, and the phrase marked by -de in 29. This is because the examples in 32 are compounds while the verb, −de, and the phrase marked by -de in 29 do not form a compound, particularly given the fact that -de is an inflectional and grammatical suffix, not a derivational suffix. Therefore, there is no good reason for Huang et al. to treat the V and -de in 29 and the ones in 30 differently. Given the fact that -de is an inflectional suffix in both 29 and 30, I propose that 29 should have the structure in 37, not the one in 31. In 37, the main verb is chang ‘to sing’ and the subordinate clause S2 is licensed by the inflectional suffix -de. This subordinate clause functions as an adjunct or an argument-like adjunct (see Ernst 1996). Moreover, the null element in 37 is subcategorized for by haoting in S2.

-

(37)

[S1 Ni [VP change-de [S2 Ø tebie haoting]]] (Ø=null element)

Third, given the fact that -de is an inflectional suffix in 30 as well, Huang et al.’s analysis of the verb and the de in a resultative V-DE construction as a lexical compound analogous to an RVC does not hold.

Fourth, ya is not a reliable diagnostic for the structure of resultative V-DE’s like 30. Recall that, according to Huang et al. (2009), the interjection ya cannot be inserted between the verb and its postverbal NP object, though it can be used after that object. However, in 38b ya can be inserted between the verb 砸 za ‘to smash’ and the overt NP after -de even though this overt NP in this case is semantically the Patient argument of the verb. Following Huang et al.’s reasoning, 杯子 beizi ‘cup’ in 38a is not the object of the verb za. However, there is good reason to believe that Huang et al. would analyze 38a and 30 as having the same structure.

-

(38) a.

张三砸得杯子都碎了。

-

Zhangsan__za-de__beizi__dou__sui-le.

-

Zhangsan__smash-de__cup__all__break.in.pieces-perf

-

Zhangsan smashed all the cups into pieces.

-

-

b.

张三砸得呀, 杯子都碎了。

-

Zhangsan__za-de__ya,__beizi__dou__sui-le.

-

Zhangsan__smash-de__ya,__cup__all__break.in.pieces-perf

-

Zhangsan smashed all the cups into pieces.

-

Moreover, as shown in 39b and 39c, ya can have the same use as in 36. That is, analogous to its use in 36, ya in 39 can be inserted after wo (see 39b) and cannot be inserted between chang-de and wo (see 39c). However, the NP in question in 39 is undoubtedly not the syntactic direct object of the verb 唱 chang ‘to sing’, as wo is not the entity being sung. This further shows that the insertion of ya is not a reliable diagnostic as to whether the NP in the clause marked by de is syntactically the direct object of the verb right before de. Footnote 14 In this regard, it should be stressed that Huang et al. (2009) incorrectly assume that, as long as ya can be used after the NP following de and cannot be used between V-DE and that NP, the NP in question should be analyzed as the direct object of the verb right before -de. This wrong assumption casts serious doubt on Huang et al.’s analysis of resultative V-DE constructions like 30.

-

(39) a.

那首歌唱得我哭了起来。

-

Na-shou__ge__chang-de__wo__ku-le__qilai.

-

that-cl__song__sing-de__I__cry-perf__inch

-

That song made me start to cry.

-

-

b.

那首歌唱得我呀, 哭了起来。

-

Na-shou__ge__chang-de__wo__ya,__ku-le__qilai.

-

that-cl__song__sing-de__I__ya__cry-perf__inch

-

That song made me start to cry.

-

-

c.

?那首歌唱得呀, 我哭了起来。

-

?Na-shou__ge__chang-de__ya,__wo__ku-le__qilai.

-

that-cl__song__sing-de__ya__I__cry-perf__inch

-

Intended: That song made me start to cry.

-

It should be pointed out that Huang (1988) discusses V-DE constructions like 40. There is good reason to assume that Huang would analyze 39a and 40 in the same way. However, Huang (1988, 1992) never explicitly says that Zhangsan in 40 is the direct object of zui. What Huang (1988) does claim is that Zhangsan is the “external object” of Vʹ in 41, Huang’s deep structure for 40. Huang (1988: 299) assumes that V1 in 41 can move to the position of “INFL” and then assign “Accusative Case” to Zhangsan. He, however, does not provide any motivation for the movement operation. Moreover, it is not clear how zui, an unaccusative verb, can have case-assigning capability. In any case, Huang’s analysis of 40 as 41 does not provide any support or evidence for a claim that Zhangsan in 40 is the direct object of zui or a claim that wo in 39a is the direct object of chang.

-

(40)

这瓶酒醉得张三站不起来。(Adapted from Huang 1988: 294)

-

Zhe-ping__jiu__zui-de__Zhangsan__zhan-bu-qilai.

-

this-bottle__liquor__drunk-de__Zhangsan__stand-cannot-up

-

This bottle of liquor got Zhangsan so drunk that he couldn’t stand up.

-

-

(41)

Deep structure for 40 (Huang 1988: 299)

Finally, while Huang et al. (2009: 85) claim that wo ‘me’ in 30 is the object of the verb qi ‘to annoy’, this claim seems to be incompatible with the underlying structure they propose for 30. As 42 shows, underlyingly ‘me’ is not the object of ‘to annoy’. Equally important, even after “annoy-de” moves from V to v, ‘me’ in 42 still is not the object of ‘to annoy’.Footnote 15

-

(42)

Underlying structure for 30 (Huang et al. 2009: 86)

3 An alternative classification and analysis of the V-DE construction

In this section, I offer an alternative classification and analysis of the V-DE construction, and we will start with its classification.

I propose that a classification of the V-DE construction can be made first on the basis of whether the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is syntactically predicative or not. That is, a distinction between predicative and non-predicative V-DE constructions can be made. In this classification, the non-entity part of the constituent after -de refers, for example, to hen xiang in 43a and to dou teng le in 43c.

-

(43) a.

张三昨晚睡得很香。(=12)

-

Zhangsan__zuowan__shui-de__hen__xiang.

-

Zhangsan__last.night__sleep-de__very__sound

-

Zhangsan had a sound sleep last night.

-

-

b.

张三吃得很胖。

-

Zhangsan__chi-de__hen__pang.

-

Zhangsan__eat-de__very__fat

-

Zhangsan ate to the effect of having become overweight.

-

-

c.

张三坐得背都疼了。(=3)

-

Zhangsan__zuo-de__bei__dou__teng-le.

-

Zhangsan__sit-de__back__emphasis__hurt-perf

-

Zhangsan sat to the extent that his back hurt.

-

Most V-DE constructions are predicative V-DE’s. First of all, 43a and 43b, whose de-parts have an overt AP alone, are predicative V-DE constructions. Previous accounts typically treat the de-part in examples like 43a as a phrase rather than a clause, as seen in previous analyses of such sentences by Li and Thompson (1981), Li (1990), and Huang et al. (2009) and in Shi’s (1990: 48) analysis of such examples as having the structure in 44.

-

(44)

NP [VP1 [VP2 V de] AdjP]

However, as argued above with respect to Li and Thompson’s analysis of V-DE constructions like 43a and 43b, the de-part in such sentences is in fact a clause with a null subject because the overt AP constituent in these de-parts is not only predicative but also functions as the predicate of a clause. We have seen evidence for this from the difference between adjectives and adverbs in Mandarin and from negation, the use of the perfective marker -le, and the use of the A-not-A form in the -de part.

Second, when the de-part has an overt VP alone, the V-DE construction is also predicative. As discussed earlier, jiao in 23a (repeated as 45a below) is undoubtedly the predicate of a clause, as evidenced by the fact that it can be used in the V-not-V form (see 45b) and can be followed by the perfective marker -le (see 45c).

-

(45)

a. 张三疼得直叫。

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__zhi__jiao.

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__continuously__yell

-

Zhangsan hurt so much that he yelled and yelled.

-

-

b.

张三疼得叫没叫?

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__jiao-mei-jiao?

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__yell-not-yell

-

Did Zhangsan yell due to his pain?

-

-

c.

张三疼得叫了又叫。

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__jiao-le__you__jiao.

-

Zhangsan__hurt-de__yell-perf__again__yell

-

Zhangsan hurt so much that he yelled over and over.

-

Finally, when the de-part is resultative and is a full-fledged clause (e.g. 43c), the AP or VP in the clause is obviously predicative. As a construction, the V-DE construction has its own syntax and semantics. As a constraint for this construction, the non-entity part of the constituent after -de generally must be about and syntactically predicated of one overt NP after -de when there is such an overt NP in a resultative de-part. So in the case of 43c, which involves an overt NP after -de, 疼 teng ‘hurt’ is predicative and the hurting needs to be about Zhangsan’s back.

As for non-predicative V-DE constructions, they are those cases in which the de-part has an overt adverbial phrase alone, as shown in 46. The adverbial phrase hen in 46, unlike an adjectival phrase seen in 43a and 43b, is not predicative and as a result does not share the characteristics of predicative adjectival phrases discussed in section 2. For example, the change of these adverbial phrases from their positive form to a negative form or vice versa often results in an ungrammatical sentence, as evidenced by the unnaturalness, if not ungrammaticality, of 47.Footnote 16

-

(46)

张三的衣服多得很。(=9)

-

Zhangsan-de__yifu__duo-de__hen.

-

Zhangsan-gen__clothes__many-de__very

-

Zhangsan has a lot of clothes.

-

-

(47)

?张三的衣服多得不很。

-

?Zhangsan-de__yifu__duo-de__bu__hen.

-

Zhangsan-gen__clothes__many-de__not__very

-

Intended: Zhangsan does not have a lot of clothes.

-

I propose that, in addition to the distinction between predicative and non-predicative V-DE constructions, a further distinction can be made within predicative V-DE’s according to whether the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is semantically about the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de or about a specific entity (i.e. participant). When the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is semantically about the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de, we have an “eventuality-predicative V-DE construction”. On the other hand, when the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is semantically about a specific entity, we have an “entity-predicative V-DE construction”. In both types of the predicative V-DE construction, the semantic predicative relationship established between the non-entity part of the de-part on the one hand and the specific entity or the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de on the other must be part of the meaning expressed by the V-DE construction in question.

As mentioned above, the V-DE construction has a constraint that, when there is an overt NP in a resultative de-part, the non-entity part of the constituent after -de generally must be about and predicated of this overt NP. As a result, such predicative V-DE constructions as 43c are also entity-predicative V-DE constructions. Moreover, when the de-part has an overt VP alone, the VP is also semantically predicated of a specific entity, presumably because of the anomaly of the semantic composition of the overt VP after -de and the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de. For example, in 45a what 叫 jiao ‘yell, shout’ is semantically predicated of is Zhangsan, not Zhangsan’s hurting. This is further due to the fact that semantically and pragmatically “Zhangsan’s hurting yells” is not well-formed.

However, when the de-part has an overt AP alone, a more complex scenario arises. First, we may unambiguously get an entity-predicative V-DE construction or an eventuality-predicative V-DE construction. For example, 43b can only be an entity-predicative V-DE construction in which being fat is about Zhangsan. For another example, 43a can only be an eventuality-predicative V-DE construction in which being sweet and sound is about the sleeping by Zhangsan. Second, when the de-part has an overt AP alone, it is possible for at least some V-DE constructions to be analyzed either as entity V-DE constructions or as eventuality V-DE constructions, as shown in 48.Footnote 17

-

(48)

张三玩儿得很开心。

-

Zhangsan__wanr-de__hen__kaixin.

-

Zhangsan__play-de__very__happy

-

a.

Zhangsan played happily.

-

b.

Zhangsan played to the effect that he was very happy.

-

In this case, the distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions nicely captures Li and Thompson’s intuition as to the ambiguity in examples like 48, in which the first reading arises from an eventuality-predicative V-DE construction and the second one from an entity-predicative V-DE construction. As argued above, when the de-part has an overt AP alone, the de-part in fact is a clause containing the AP and a null subject. In the case of the first reading of 48, the null element refers to the eventuality of playing; in the case of the second reading, the null element refers to Zhangsan.

Meanwhile, the distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions nicely captures and explains Li’s (1990) intuition as to the difference between sentences like 43a and 43b. As far as the de-part is concerned, Li would analyze 43a as containing a descriptive expression and 43b as containing a resultative expression. Recall that she characterizes the de-part of 43a as an AP and the one of 43b as a clause. As discussed with respect to Li and Thompson’s (1981) classification and analysis of V-DE constructions, both examples like 43a and the ones like 43b involve a clausal de-part. On the basis of my distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions, 43a and 43b do not differ in the category of the de-part, but in what the overt AP is a predicate of and what the null element in the clausal de-part coreferential with. In the case of 43a, an eventuality-predicative V-DE construction, the overt AP is predicated of an eventuality and the null element in the de-part is conferential with the eventuality of sleeping by Zhangsan. In the case of 43b, an entity-predicative V-DE construction, the overt AP is predicated of a specific participant and the null element in the de-part refers to the entity of Zhangsan.

Recall that Li (1990) also mentions that “descriptive” V-DE constructions do not allow an overt NP in the de-part. However, she does not provide an explanation for this. My distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions, nevertheless, can also account for the observation mentioned by Li (1990). Specifically, Li’s “descriptive” V-DE constructions are eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions in my terms. When an overt NP is used to replace the null subject of the de-part in eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions like 43a, an entity-predicative V-DE construction arises as long as the de-part is semantically well-formed and pragmatically plausible and can be interpreted as an achieved effect of the eventuality before -de. In this case, the original eventuality-predicative V-DE construction ceases to be an eventuality-predicative V-DE construction and becomes an entity-predicative V-DE construction.

To summarize my classification of the V-DE construction, two types of V-DE constructions, predicative and non-predicative, can be distinguished according to whether the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is syntactically predicative or not. Moreover, within predicative V-DE constructions, a further distinction can be made between entity-predicative V-DE constructions and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions. The different types of V-DE constructions are functionally unified by the fact that the de-part in all the different types serves the function of providing a comment about what has been achieved by the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de, whether it is an achieved effect, quality, degree, result, or state. With respect to the distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions, it nicely captures the intuition behind Li and Thompson’s (1981) distinction between “manner” V-DE constructions and “extent” V-DE constructions and behind Li’s (1990) distinction between “descriptive” V-DE constructions and “resultative” V-DE constructions. Moreover, the distinction between entity-predicative and eventuality-predicative V-DE constructions offers a natural account of the ambiguity cases discussed by Li and Thompson as well as the fact of “descriptive” V-DE constructions not allowing an overt NP discussed by Li (1990).

With the classification of V-DE constructions settled, the next question is how to analyze the V-DE construction. With respect to this, let us first consider non-predicative V-DE constructions like 46 above. As mentioned earlier, the de-part of such V-DE constructions involve a non-predicative AdvP. As a result, these V-DE constructions have the structure in 49. In this structure, the AdvP is licensed by the inflectional suffix -de and is used as an adjunct that modifies the V.

-

(49)

[S NP [VP [VP V-de] AdvP]]

As for the structure of predicative V-DE constructions, let us first examine eventuality V-DE constructions exemplified by 43a. Given that the de-part in such V-DE constructions is a clause involving a null subject, I propose that these eventuality V-DE constructions have the following structure:

-

(50)

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø AP ]]] (Ø=null element=eventuality)

As seen with the structure in 37, the S2 in 50 is a subordinate clause licensed or subcategorized for by the inflectional suffix -de. This subordinate clause, like the AdvP in 49, functions as an adjunct that modifies the main predicate, namely the V in 50.

Note that not only sentences like 43a but also examples like 51a have the structure in 50.

-

(51) a.

张三疼得很厉害。(=2)

-

Zhangsan__teng-de__hen__lihai.

-

Zhangsan__ache-de__very__severe

-

Zhangsan has/had a terrible pain.

-

-

ᅟ

b. 双方的损耗都很厉害。

-

Shuangfang-de__sunhao__dou__hen__lihai.

-

two.sides-gen__loss__both__very__severe

-

The loss for both sides was very severe.

-

-

ᅟ

c. 双方的损耗都不厉害。

-

Shuangfang-de__sunhao__dou__bu__lihai.

-

two.sides-gen__loss__both__not__severe

-

The loss for neither side was severe.

-

-

ᅟ

d. 双方的损害都厉害不厉害?

-

Shuangfang-de__sunhao__dou__lihai__bu__lihai?

-

two.sides-gen__loss__both__severe__not__severe

-

Was the loss for both sides severe or not?

-

-

ᅟ

e. 双方的损耗比上次都厉害了很多。

-

Shuangfang-de__sunhao__bi__shangci__dou__lihai-le__henduo.

-

two.sides-gen__loss__than__last.time__both__severe-perf__much

-

The loss for both sides was much more severe than last time.

-

In the case of 51a, it has the structure in 50 because lihai in it, like xiang in 43a, is also adjectival and predicative and serves as the predicate of a clause marked by -de. This can be seen from the fact that lihai can be used as a predicate in a single clause (see 51b), can be negated (see 51c), can be used in the V-not-V form (see 51d), and can be used with the perfective marker -le (see 51e). Moreover, lihai in 51a (like xiang in 43a) is not only predicative but also semantically predicated of an eventuality, namely Zhangsan’s aching.

In addition, eventuality-predicative constructions like 52 and 53 also have the structure in 50.

-

(52)

张三跑得像旋风一样。

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__xiang__xuanfeng__yiyang.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__like__whirlwind__same

-

Zhangsan ran like a whirlwind.

-

-

(53)

?他跑得快到能追上兔子。(Huang et al. 2009: 87)

-

?Ta__pao-de__kuai-dao__neng__zhuishang__tuzi.

-

he__run-de__fast-till__be.able.to__catch.up.with__rabbit

-

He ran fast enough to catch up with a rabbit.

-

With respect to 52, it should be pointed out that xiang xuanfeng yiyang is an AP that is headed by the adjective yiyang. Moreover, it is semantically plausible for this AP to be predicated of the eventuality of Zhangsan’s running. As a result, the structure in 50 is assigned to examples like 52 as well. As for 53, kuai-dao neng zhuishang tuzi in it is an AP that is headed by the adjective kuai ‘fast’, although this AP is more complex than the one hen lihai in 51a, for example, in the sense that within it there is a clause introduced by dao. As a result, 53 can also be analyzed as having the structure in 50.

As for the structure of entity-predicative V-DE constructions, examples like 43b, whose de-part has an overt AP alone, have the structure in 54. This structure can be said to be the same as the one in 50. The two differ only in what the null subject refers to. In the case of 54, the null element refers to a specific entity, but the null subject in 50 refers to the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective right before -de.

-

(54)

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø AP ]]] (Ø=null element=entity)

Next, with respect to entity-predicative V-DE constructions like 45a whose de-part has an overt VP alone, they have the structure in 55. Like 54, the null element in 55 also refers to an entity. Moreover, in both 54 and 55, the S2 is a subordinate clause licensed by the inflectional suffix -de. This subordinate clause, like the one in 50, functions as an adjunct that modifies the V, the main predicate of the whole structure.

-

(55)

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø VP ]]] (Ø=null element=entity)

Finally, with respect to entity-predicative V-DE constructions like 56–57, 59, and Huang et al.’s (2009) example in 30 (repeated as 58 below), their de-parts are all semantically the achieved effect of the eventualities before -de and all have an overt noun phrase which the AP or VP in the de-part is predicated of. Recall that there is a constructional constraint of the V-DE construction that, if there is any overt NP between -de and the AP or VP in a resultative de-part, the AP or VP must generally be semantically and syntactically predicated of this overt NP. Given this, I propose that V-DE constructions like 56–59 all have the structure in 60, which involves a full-fledged de-clause. Like the structures in 50 and 54–55, the S2 in 60 is an adjunct modifying the main predicate, the V in the structure, and is a subordinate clause licensed by the inflectional suffix -de. Moreover, the NP2 in 60 is an argument of the verb or adjective in S2 and is subcategorized for by this verb or adjective.

-

(56)

张三坐得背都疼了。(=3)

-

Zhangsan__zuo-de__bei__dou__teng__le.

-

Zhangsan__sit-de__back__emphasis__hurt__sfp

-

Zhangsan sat to the extent that his back hurt.

-

-

(57)

张三跑得鞋都掉了。

-

Zhangsan__pao-de__xie__dou__diao-le.

-

Zhangsan__run-de__shoe__emphasis__fall.off-perf

-

Zhangsan ran to such an extent that his shoes fell off.

-

-

(58)

他气得我不想写信了。(Huang et al. 2009: 84)

-

Ta__qi-de__wo__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__annoy-de__me__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

He annoyed me so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

(59)

那段路走得他好累。

-

Na-duan__lu__zou-de__ta__hao__lei.

-

that-stretch__road__walk-de__he__very__tired

-

He walked on that stretch of road and that stretch of road made him very tried.

-

-

(60)

[S1 NP1 [VP V-de [S2 NP2 AP/VP ]]]

With respect to 56–59, 56–57 have the structure in 60 because bei ‘back’ is not an argument of zuo ‘to sit’ in 56 and neither is xie ‘shoe’ an argument of pao ‘to run’ in 57. Meanwhile, teng ‘to hurt’ in 56 is predicated of the back and diao ‘to fall off’ in 57 is predicated of the shoes. This clearly shows that both 56 and 57 involve a distinct clause after -de. In the case of 59, ta cannot be the syntactic object of zou ‘to walk’ because it is the Agent of the walking action and because zou is an unergative verb when it means ‘to walk’. Moreover, due to the fact that Mandarin is essentially an SVO language, there is no syntactic basis for ta to be the syntactic subject of zou. Given this and given the fact that lei in 59 is predicated of ta, ta should be analyzed as the syntactic subject of a distinct clause after -de, just as xie ‘shoe’ in 57 is analyzed as the subject of a separate clause after -de. Therefore, there are good reasons for analyzing 56–57 and 59 as having the structure in 60.

The question is why we also analyze 58 as having the structure in 60. The answer is that this analysis is motivated by the fact that de can introduce a clause and there is independent evidence for this from examples like 56–57. Moreover, related to this is the fact or constraint mentioned above, namely that, if there is any overt NP between -de and the AP or VP in a resultative de-part, the AP or VP generally must be semantically and syntactically predicated of this overt NP. This can be best seen from the contrast between 61a and 61b.Footnote 18 61a is grammatical because dun can be interpreted as being predicated of the knife. On the other hand, 61b is bad because the de-part is semantically odd and pragmatically implausible. Due to these observations and to the fact that bu xiang xie xin in 58 can be predicated of the overt NP wo right after -de, it seems reasonable to analyze the overt NP wo ‘I’ in 58 as being the overt subject of the de-clause. As for the fact that wo can be interpreted as the Patient argument of qi, it is simply due to the fact that this is pragmatically plausible and semantically compatible, and is not due to a syntactic configuration in which wo is analyzed as the direct object of the matrix verb.

-

(61) a.

张三砍得刀都钝了。

-

Zhangsan__kan-de__dao__dou__dun-le.

-

Zhangsan__cut-de__knife__emphasis__dull-perf

-

Zhangsan cut (it/them) with a knife to the extent that the knife became dull.

-

-

b.

*张三砍得骨头很累。

-

*Zhangsan__kan-de__gutou__hen__lei.

-

Zhangsan__cut-de__bone__very__tired

-

In this respect, it should be pointed out that, if 60 is the shared structure for 56–59, it can be seen that NP2 in 60 may or may not be a semantic argument of the matrix verb. As discussed above, xie in 57 is obviously not an argument of pao ‘to run’, though ta in 59 can be interpreted as an argument of zou ‘to walk’. Moreover, even in those cases where NP2 in 60 can be interpreted as an argument of the matrix verb, it is not necessarily a Patient. This can be seen from the contrast between 58 and 59. Although wo in 58 and ta in 59 both correspond to the NP2 in 60 and can both be understood as a semantic argument of the corresponding main predicate, ta in 59 semantically is an Agent argument of zou ‘to walk’ and wo in 58 can be interpreted as the Patient argument of qi ‘to annoy’. Therefore, NP2 in 60 is not necessarily a Patient argument of the matrix verb.

However, there are two things that 56–59 have in common. First, we have seen their shared structure in 60, in which NP2 is the subject of the clause right after de. Second, 56–59 are also unified by the fact that in their shared syntactic structure in 60, NP1 can be interpreted as a Causer and NP2 can be understood as a Causee. In this case, the main predicate and the predicate of the clause marked by -de semantically form a causative relationship (see also Huang 1988 and Li 1998), which can be regarded as part of the constructional meaning of V-DE constructions of this specific type. For example, in 57, the shoes’ falling off takes place as a result of Zhangsan’s running and is caused by Zhangsan’s running. In this case, Zhangsan can be regarded as the Causer and the shoes can be understood as the Causee.

The causative interpretation of the V-DE construction having the structure of 60 can be compared with the causative relationship between the two components of an RVC.Footnote 19 In fact, what is expressed by 56, 57, and 59 can also be roughly expressed by RVCs, as shown in 62, in which the three sentences correspond to 56, 57, and 59 respectively. In each of the three examples in 62, the first NP corresponds to NP1 in 60 and can be interpreted as the Causer, and the second NP corresponds to NP2 in 60 and can be understood as the Causee.

-

(62) a.

张三坐疼了背。

-

Zhangsan__zuo-teng-le__bei.

-

Zhangsan__sit-hurt-perf__back

-

Zhangsan’s back hurt as a result of his sitting (for too long a time).

-

-

b.

张三跑掉了鞋。

-

Zhangsan__pao-diao-le__xie.

-

Zhangsan__run-fall.off-perf__shoe

-

Zhangsan’s shoes fell off as a result of his running.

-

-

c.

那段路走累了他。

-

Na-duan__lu__zou-lei-le__ta.

-

that-stretch__road__walk-tired-perf__he

-

He walked on that stretch of road and that stretch of road made him very tried.

-

Note that it is not always the case that a V-DE construction with the structure of 60 can be expressed by an RVC. In fact, 58 cannot be expressed by an RVC. This observation leads to differences between the V-DE construction and the Mandarin RVC. First, the two components of an RVC form a compound, a word-level entity, but the matrix verb of a V-DE construction like 56 and the predicate of the clause marked by -de are not in the same clause and obviously do not form a compound. This difference can account for the fact that 58 cannot be expressed by an RVC. This is because an RVC, as a word-level entity, obeys the “Lexical Integrity Principle”, which says that “no phrase-level rule may affect a proper subpart of a word” (Huang 1984b: 60; cf. Di Sciullo and Edwin 1987: 49). For example, the result component 累 lei ‘tired’ in 走累 zou-lei ‘walk-tired’ in 62c can be modified with a degree modifier like hen ‘very’ when used separately, as shown in 63a.Footnote 20 However, the same component cannot be modified in the same way when used in an RVC, as shown in 63b (cf. 62c). In the case of 58, the verb xie ‘to write’ is preceded by xiang ‘to want’, which is negated by bu ‘not’, and there is no way for the matrix verb qi ‘to annoy’ to form an RVC with these three elements or with the first two (i.e. bu and xiang). As a result, 58 cannot be expressed by an RVC, as shown by the ungrammaticality of 64.

-

(63) a.

他很累。

-

Ta__hen__lei.

-

he__very__tired

-

He is/was very tired.

-

b.

*那段路走很累了他。

-

*Na-duan__lu__zou-hen-lei-le__ta.

-

that-stretch__road__walk-very-tired-perf__he

-

Intended: He walked on that stretch of road and that stretch of road made him very tried.

-

-

-

(64) a.

*他气不想写了我信。

*Ta__qi-bu-xiang-xie-le__wo__xin.

he__annoy-not-want-write-PERF__I__letter

-

b.

*他气不想了我写信。

-

*Ta__qi-bu-xiang-le__wo__xie__xin.

-

he__annoy-not-want-perf__I__write__letter

-

Intended for both: He annoyed me so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

b.

Second, as the predicate of the clause marked by -de in the case of the V-DE construction does not form a compound with the matrix predicate, it is more flexible in the sense that it can be modified by degree modifiers or can be extended in some other way. For example, 累 lei ‘tired’ in 59 can be modified with 好 hao ‘very’, a degree modifier in this case. Third, when both the Causer and the Causee are overtly expressed, they are expressed in the same clause in the case of an RVC, but are realized in two distinct clauses in the case of a V-DE construction. For example, Zhangsan and xie are in two distinct clauses in 57, a V-DE construction, but they are in the same clause in 62b when an RVC is used.

After a little digression devoted to a comparison of RVCs and V-DE constructions,Footnote 21 let us come back to the examples in 56–59 and their shared structure in 60. In this case, it should be pointed out that the analysis of 58 as having the structure in 60 is not complete without considering the fact that wo in 58 can be introduced by 把 ba (see 65) and can be used before 被 bei (see 66), a passive morpheme in Mandarin. This is because these facts are often used to support an analysis that treats wo in 58 as the syntactic object of the verb qi (see, for example, Li 李临定 1963, Loar 2011, Shi 1990). The underlying assumption is that the NP introduced by ba and the syntactic subject of a passive sentence formed with bei both correspond to the direct object of the active counterpart or to the “O” of the counterpart with an SVO order. However, as shown in 67–68, this assumption is invalid. This is because neither the ba-NP in 67 nor the NP before bei in 68 can be said to correspond to a postverbal direct object of the verb in its active form. In fact, the direct object, if any, is the postverbal NP in 67 and 68. Furthermore, 65–66 do not really cause a problem to my analysis in 60 because on my account 65 and 66 have a different structure than 58 and both involve a null subject instead of an overt subject in the de-part.

-

(65)

他把我气得不想写信了。

-

Ta__ba__wo__qi-de__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__ba__me__annoy-de__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

He annoyed me so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

(66)

我被他气得不想写信了。

-

Wo__bei__ta__qi-de__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

I__pass__him__annoy-de__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

I was annoyed by him so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

(67)

张三把枪口对准了敌人。

-

Zhangsan__ba__qiangkou__duizhun-le__diren.

-

Zhangsan__ba__gun.point__point-perf__enemy

-

Zhangsan pointed the gun at the enemy.

-

-

(68)

他被歹徒下了毒手, 不幸牺牲了。(Lü et al. 吕叔湘等 1999: 68; glosses and translation mine)

-

Ta__bei__daitu__xia-le__dushou,__

-

he__PASS__gangster _put.down-PERF__murderous.scheme__

-

buxing__xisheng__le.

-

unfortunately__die__SFP

-

Murderous hands were laid on him by the gangsters and he sadly died.

-

As seen earlier, one of the important gains of analyzing 58 as having the structure in 60 is that we can give a unified analysis of the syntactic structure of all the examples in 56–59 and see the causative relation shared by such V-DE constructions. Taking into account all the structures in 49, 50, 54, 55, and 60 (repeated as 69a, 69b, 69c, 69d, and 69e respectively), we can summarize the structures of the V-DE construction as 70.

-

(69) a.

[S NP [VP [VP V-de] AdvP]] (=49)

-

b.

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø AP ]]] (Ø=null element=eventuality) (=50)

-

c.

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø AP ]]] (Ø=null element=entity) (=54)

-

d.

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø VP ]]] (Ø=null element=entity) (=55)

-

e.

[S1 NP1 [VP V-de [S2 NP2 AP/VP ]]] (=60)

-

b.

-

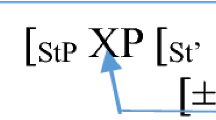

(70)

Structures of the V-DE construction

-

a.

[S NP [VP [VP V-de] AdvP]] (e.g. 46)

-

b.

[S1 NP [VP V-de [S2 Ø PredP ]]] (Ø=null element) (e.g. 43a, 43b, 45a)

-

c.

[S1 NP1 [VP V-de [S2 NP2 PredP ]]] (e.g. 57–58)Footnote 22

-

a.

In 69, 69a is the structure for the non-predicative V-DE construction and 69b-69e are for the predicative V-DE construction. Among 69b-69e, 69b is the structure for the eventuality-predicative V-DE construction and the rest are for the entity-predicative V-DE construction. In 70, 70a is identical to 69a, and 70b incorporates the structures in 69b, 69c, and 69d. Moreover, I use “PredP” in 70b (and also 70c) to stand for a predicate phrase, which, in Mandarin, is typically an AP or VP. With respect to 70c, the PredP in the de-clause can be a VP as seen from examples like 57–58. Moreover, it can also be an AP if words like 红hong ‘red’ are analyzed as adjectives in sentences like 71.

-

(71)

张三气得脸都红了。

-

Zhangsan__qi-de__lian__dou__hong-le.

-

Zhangsan__angry-de__face__emphasis__red-perf

-

Zhangsan was so angry that his face even turned red.

-

In both 69a and 70a, the AdvP is licensed by the inflectional suffix -de and it functions as an adjunct that modifies the V. In 69b-d and 70b, the null element is subcategorized for by the verb or adjective in S2, which is licensed by -de and is a subordinate clause modifying the main predicate, namely the V in the structures. Likewise, in 69e and 70c the NP2 is subcategorized for by the verb or adjective in S2. This S2, like the other ones, is a subordinate clause licensed by the grammatical morpheme -de and serves as an adjunct modifying the main predicate of the V-DE construction. It should also be pointed out that the NPs in 69a-d and 70a-b and the NP1’s in 69e and 70c are the subject of the clause that has the verb or adjective right before -de as its main predicate.Footnote 23

Several points need to be made clear as to my analysis of the V-DE construction. First, the analysis is consistent with Huang’s (1988) analyzing the verb or adjective before -de as the main predicate of the whole V-DE construction. In this regard, it should be pointed out that Huang (1988, 1992) does not discuss cases like 46 or their structure. However, even the structure of 70a is consistent with the spirit of Huang’s analysis, as the AdvP after -de is not predicative and is by no means the main predicate of the whole V-DE construction.

Second, in all the structures of 70, -de is an inflectional suffix attached to the verb or adjective right before it. As an inflectional suffix, -de of the V-DE construction serves the grammatical function of marking the V-DE construction. It is the indicator of the V-DE construction just as bei is an indicator of the passive construction in Mandarin. Moreover, if it is right to derive the suffix -de from the verb de meaning ‘to obtain’ (see above), then its change from a verb to a verbal suffix is consistent with a well-established path of grammaticalization, namely a verb’s gradual change into an affix (see Hopper and Traugott 2003 for discussion). The fact that the de-part of the V-DE construction expresses an achieved effect, quality, degree, result, or state is consistent with the proposal that the suffix -de is historically derived from a verb that means ‘to obtain’. This historical relationship, however, does not lead to any conclusion that de in the V-DE construction is currently still a verb. Crucially, if de were really a regular verb in the contemporary V-DE construction, its ubiquitous combination with adjectives and verbs would be a mystery no matter how compounding is productive in Chinese. In this regard, note also the fact that true compound verbs formed with de like 取得 qude ‘to achieve’ and 获得 huode ‘to get, to obtain’ are not large in number. In addition, the fact that -de in the V-DE construction is pronounced with the neutral tone also casts doubt on any proposal that it is a regular verb.

Third, as sentences like 58 (repeated as 72 below), on my proposal, also have the structure in 70c, my analysis of such V-DE constructions differ from Huang et al.’s (2009). Recall that, when the verb right before -de is transitive and when there is an NP after -de that is semantically the Theme or Patient argument of this verb, Huang et al. (2009) analyze the NP after -de as the direct object of the verb before -de and propose that there is a “Pro” in the clause after the overt NP. As discussed earlier, there is no convincing evidence for such an analysis. When there is no evidence for a more complex structure and when a simpler structure can account for the same set of linguistic facts in a neat way, the simpler structure should he preferred. If my proposal is on the right track, my analysis of 72 as having the structure in 70c is incompatible with Huang et al’s (2009: 88) descriptive generalization in 73. If my analysis is right, Huang et al.’s characterization of the overt NP as “object” is not appropriate.

-

(72)

他气得我不想写信了。(Huang et al. 2009: 84)

-

Ta__qi-de__wo__bu__xiang__xie__xin__le.

-

he__annoy-de__me__not__want__write__letter__sfp

-

He annoyed me so much that I didn’t want to write the letter.

-

-

(73)

Huang et al’s descriptive generalization (2009: 88)

-

A phonetically overt NP object is permitted postverbally only in the resultative V-de construction.

-

Finally, the part introduced by de, in most cases, contains a predicate. It should be noted that not all de-parts contain a predicate (see 70a). I will use [+Predicative] to refer to a de-part that contains a predicate and use [−Predicative] to mean a de-part that does not contain a predicate. As the de-part in both 70b and 70c is predicative, it can be concluded that the de-part in the V-DE construction is predicative in most cases. Moreover, we can use two features to characterize a V-DE construction. One feature is [±Predicative] and the other is [±Entity]. When the non-entity part in the constituent after -de is semantically about a specific participant rather than about the eventuality expressed by the verb or adjective before -de, the V-DE construction carries the [+Entity] feature. Otherwise, it has the [−Entity] feature. With the features of [±Predicative] and [±Entity], there are four logical combinations: (i) [+Predicative; +Entity] (e.g. 72), (ii) [+Predicative; −Entity] (e.g. 43a), (iii) *[−Predicative; +Entity], and (iv) [−Predicative; −Entity] (e.g. 46). Among the four possibilities, three are attested. As for the third possibility, it is unattested due to the fact that, when the non-entity part of the constituent after -de is semantically about a specific entity, it is always predicative and carries the [+ Predicative] feature. This is so, regardless of whether this specific entity in question is overtly expressed in the de-part or not. Given the incompatibility of [−Predicative] and [+Entity], the third logical possibility is thus unattested.

4 A remaining issue: 好心焦 hao xinjiao ‘so anxious’ and other cases

Any comprehensive account of the V-DE construction needs to take the grammaticality of sentences like 74 into consideration.

-

(74)

我等得他好心焦。

-

Wo__deng-de__ta__hao__xinjiao.

-

I__wait-de__he__very__anxious

-

I waited for him so anxiously.

-

On my account 74 should have the structure in 75a, and on Huang et al.’s (2009) account it would have the structure in 75b.

-

(75) a.

[S1 Wo [VP deng-de [S2 ta hao xinjiao]]]

-

b.

Wo deng-de ta [S Pro hao xinjiao]

However, sentences like 74 pose a problem to both accounts. Specifically, 74 is problematic for my account because the interpretation of the sentence is not consistent with the expected meaning from the structure in 75a. It is potentially also problematic for Huang et al’s account if they adopt the same assumption made in Huang (1992), namely that the interpretation of the Pro in 75b obeys the Minimal Distance Principle (MDP), by which the Pro should be controlled by the minimal or closest c-commanding noun phrase. While Huang et al. (2009) do not explicitly mention the MDP when discussing the V-DE construction, the fact that they offer a similar structure (see 42) to the one proposed by Huang (1992) and resort to this principle when discussing the passive construction formed with bei leads to a reasonable conclusion that, with respect to the V-DE construction, Huang et al. (2009) do adopt the MDP. Given this, examples like 74 also pose a problem for Huang et al.’s analysis. This is because the structure in 75b leads to the interpretation that he was anxious, given that the closest NP co-commanding the Pro is ta. However, on the attested interpretation of 74, it was me who got anxious.

Given the meaning of 74, one might be tempted to dispense with the MDP and allow the Pro in 75b to be coreferential with the matrix subject as well as long as such an interpretation is semantically and pragmatically warranted. However, such a move turns out to be undesirable because it would leave the ungrammaticality of examples like 76 (see also 61b) unaccounted for.Footnote 24

-

(76) a.

*张三踢得球很累。

-

*Zhangsan__ti-de__qiu__hen__lei.

-

Zhangsan__kick-de__ball__very__tired

-

Intended: Zhangsan kicked the ball and as a result he became very tired.

-

-

b.

*张三看得书很烦。

-

*Zhangsan__kan-de__shu__hen__fan.

-

Zhangsan__read-de__book__very__vexed

-

Intended: Zhangsan read books and as a result he became very vexed.

-

Now let us turn to examples like 77. Importantly and interestingly, in addition to the (b) reading, 77 also allows the (a) reading, in which Zhangsan’s hand became numb. When examples like 77 are also taken into account, one might be again tempted to adopt Huang’s (1992) and Huang et al’s (2009) proposal on which there is a Pro in a clause starting after Lisi. Then to accommodate the (a) reading, one is again tempted to do away with the MDP and allow the Pro in the clause after Lisi to be coreferential with the matrix subject as well. This move, however, again turns out to be unattractive because they leave the ungrammaticality of examples like 78 unaccounted for.

-

(77)

张三打得李四手都麻了。

-

Zhangsan__da-de__Lisi__shou__dou__ma-le.

-

Zhangsan__hit-de__Lisi__hand__emphasis__numb-perf

-

a.

Zhangsan hit Lisi to such an extent that Zhangsan’s hand became numb.

-

b.

Zhangsan hit Lisi to such an extent that Lisi’s hand became numb.

-

-

(78)

*张三踢得球脚都肿了。

-

*Zhangsan__ti-de__qiu__jiao__dou__zhong-le.

-

Zhangsan__kick-de__ball__foot__emphasis__swollen-perf

-

Intended: Zhangsan kicked the ball to the extent that his feet got swollen.

-

Therefore, Huang et al.’s (2009) proposal would not be able to account for the reading of 74 and the first reading of 77. Moreover, given the ungrammaticality of sentences like 76 and 78, it would be an undesirable move to dispense with the MDP while following Huang’s (1992) and Huang et al.’s (2009) proposal of a Pro in the de-clause. In fact, this move would turn out to be too undesirable because it would lead to too much generation of ungrammatical strings.

Admittedly, the reading of 74 and the first reading of 77 are also problems for my analysis of the V-DE construction. However, as discussed above, proposing a Pro in the de-clause for examples like 74 and 77 instead of proposing a simpler structure without positing such an empty category does not solve the problem. The point again is that when there is no convincing evidence for a more complex structure, a simpler structure that can account for the same set of facts should be preferred.

With respect to examples like 74 and 77, it should be pointed out that they are seldom mentioned or discussed in the literature on the V-DE construction, particularly the literature written in English.Footnote 25 Ding 丁恒顺 (1989) and Sun 孙银新 (2005) are two of the first to characterize such sentences. According to Ding, the matrix verbs that are used in sentences like 74 generally express meanings such as looking for, waiting for, or hoping for. This, to a large extent, is a right characterization. However, it should be clear from 77 that verbs used in these special “subject-oriented” V-DE constructions are certainly not confined to the semantic domain mentioned by Ding 丁恒顺 (1989).

In any case, there is still the question of how to account for the grammaticality of 74 and the first reading of 77 and for the ungrammaticality of 76 and 78. As a step towards a successful account of these interesting but challenging facts, I propose that the data discussed in this section actually sheds further light on my analysis of sentences like 71 and 72 as having the structure in 70c, which does not have a null subject. Note again the fact that 74 is grammatical and 76 is not and the fact that the first reading of 77 is allowed and the intended reading of 78 is not. I would like to suggest that these facts actually show that it is desirable to analyze the resultative de-part as a full-fledged clause. As a clause, the de-part should be a string that is allowed by the grammar of Mandarin Chinese and should be semantically coherent and pragmatically plausible. Given this, 76a, for example, is bad because the de-part, a full-fledged clause starting from qiu, is semantically odd and pragmatically implausible. For another example, 78 is ill-formed because the de-part, a full-fledged clause starting also from qiu, is an ungrammatical string in Mandarin.Footnote 26 In this respect, it should be pointed out that my own account of the ungrammatical sentences like 76 and 78 is simpler and more direct than Huang et al.’s (2009) in that mine does not resort to the use of Pro and the MDP and relies directly on the well-formedness of the full-fledged clause in the de-part.

As for the well-formedness of the reading of 74 and the first reading of 77, note that, as far as the de-part is concerned, it is grammatical in both 74 and 77. Following the same reasoning behind the structure in 70c, I propose that 74 and 77 have the structure in 79a and 79b, respectively. In both structures, the S2 is a well-formed string in Mandarin in both form and meaning.

-

(79) a.

[S1 Wo [VP deng-de [S2 ta hao xinjiao]]]

-

b.

[S1 Zhangsan [VP da-de [S2 Lisi shou dou teng-le]]]

The problem is that the structure of 79a leads to the interpretation that he became anxious. This interpretation results from the systematic default interpretation of a resultative de-part with an overt NP. This systematic default interpretation, in turn, results from one constructional constraint of the V-DE construction mentioned above, namely that, when the de-part is resultative and has an overt NP between -de and the predicate of the de-clause, the AP or VP of the de-part generally needs to be predicated of one of the overt NPs in the de-part.

The constructional constraint of the V-DE construction also guides the interpretation of 79b and it correctly gives rise to the default reading of 79b, namely the second reading of 77. However, the structure of 79b itself cannot successfully account for the first reading of 77, just as the structure in 79a itself cannot successfully account for the reading of the example in 74.