Abstract

Background

The Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) model of human functioning uses the behavioral processes of acceptance, mindfulness, and values, which together compose psychological flexibility, the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being and to either change or persist when doing so serves valued ends. To increase the effectiveness of interventions in the medical treatment of diabetes, it is important to examine the effects on patients with type 2 diabetes of promoting the active component patterns of ACT. This study explores these points.

Methods

Questionnaires were administered to type 2 diabetes patients who were registered in the database of a research service provider, and data was collected and analyzed from a total of 211 patients (mean age ± SD was 58.84 years old ±10.25, 14.69% were females).

Results

Cluster analysis yielded four clusters: “Average” (average levels of acceptance, mindfulness, and values), “Flexibility” (high levels of acceptance, mindfulness, and values), “Values/low” (average levels of acceptance and mindfulness, and a low level of values), “Values/high” (average levels of acceptance and mindfulness and a high level of values). Patients in the “Flexibility” and “Values/high” clusters had significantly fewer depressive symptoms than the other clusters. However, members of the “Values/high” cluster demonstrated significantly higher glycated hemoglobin levels than those in the other clusters.

Conclusions

The results above indicate that each part of the ACT model is necessary for managing diabetes treatment while improving quality of life. The importance of values is emphasized in ACT for diabetes patients, but we argue, given our results, that acceptance and mindfulness are very important for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. This study is limited to Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. In further research, the subject population must be expanded to people from other areas and of different racial backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Control of diabetes depends greatly on self-management, meaning that attention must be paid to self-care activities. Factors largely influencing self-care behaviors are the patient’s way of thinking, emotions, stress, diabetes complications, support from medical staff, family, school, work place members, region, and health care systems, etc. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the patient’s psychological and social problems in addition to physical problems to achieve satisfactory glycemic control.

For this reason, many psychological interventions have been conducted for diabetes patients, many of which have proven effective but costly. A meta-analysis found that most such studies used 10 or more treatment sessions and that, on average, 24 h of intervention was needed to reduce HbA1c levels by 1% [1]. Thus, in clinical practice, psychological therapies are generally not used due to the time and effort they require [2].

Recently, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) has received increasing recognition as a viable alternative to other psychological therapies [3]. It has been shown that a one-day workshop style of ACT intervention is effective for diseases such as type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis [4], migraine [5, 6], obesity [7], vascular disease [8]. These studies suggest that focusing on the ACT behavioral process could possibly solve the problems concerning intervention duration and the amount of effort.

The ACT model of human functioning includes the behavioral processes of acceptance, mindfulness, and values, which together compose psychological flexibility, the ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being and to either change or persist when doing so serves valued ends [9]. Acceptance is the voluntary adoption of an intentionally open, receptive, flexible, and nonjudgmental posture with respect to moment-to-moment experience. Mindfulness helps one consciously center oneself in the here and now. It is a grounded awareness of one’s experience instead of identifying with it, resisting it, or rejecting it. Values promotes awareness of positive reinforcement that one is engaging in acting according to one’s values and enables one to focus on processes rather than results, motivating one to pursue personal goals.

Most psychological studies involving the application of cognitive-behavior therapy have concentrated on decreasing, changing, or stopping negative thoughts and emotions related to diabetes. However, the ACT model focuses on the acceptance of negative thoughts and emotions, which emphasizes values and personal goals [9].

One study found that patients receiving a one-day ACT intervention were more likely to report superior self-care activities and have glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values in the target range of under 7% 3 months after the intervention than patients who only received diabetes education [10]. Mediational analysis showed that increases in acceptance mediated improvement in HbA1c values. Because of the intervention effects of a one-day ACT workshop, as indicated by that study, the introduction of psychological therapeutic interventions into the medical treatment of diabetes on reasonable terms can be expected to become a direction of therapy. A one-day workshop ensures treatment adherence and completion, the lack of which is often the greatest obstacle to effective delivery of mental health services. In fact, a meta-analysis of 125 studies of outpatient psychotherapy found that 50% of patients prematurely terminate participation, with nearly 40% dropping out after only the first or second visit [11, 12].

Psychological flexibility includes the behavioral processes of acceptance, mindfulness, and values; however, the above-mentioned study assessed acceptance but not mindfulness, and values. It is not yet known how these behavioral processes relate to one another in support of their mutual effectiveness. To create more efficient interventions that are suited to the medical treatment of diabetes, it is important to examine the retention pattern of behavioral processes of ACT relative to diabetes. An emphasis on values may be more relevant for medical conditions such as diabetes that require significant self-management [12]. This study explores these points.

Methods

Participants

To gather data from a wide range of community samples, we used an online survey, conducted with the assistance of a marketing research service provider. From among approximately 13,203 responses by Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes registered in the database of the research service provider, we obtained valid responses from 211 individuals (mean age 58.84 years ±10.25, 14.69% female, mean illness duration 10.62 years ±8.41, rate of complication 18.14, 24.18% had cessation of treatment).

Measures

Demographics

Sociodemographic information on age, sex, complications, and treatment status were obtained via the self-reported questionnaires.

Acceptance

The Acceptance and Action Diabetes Questionnaire (AADQ), an 11-item instrument, measures the acceptance of diabetes-related thoughts and feelings and the degree to which they interfere with valued action [9]. The Japanese version of AADQ was used [13]. For psychometric concerns, three items were excluded, leaving eight-items for analysis. Respondents rated the items on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = never true of me to 7 = always true of me).

Mindfulness

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) is a 15-item instrument that measures to what extent respondents pay mindful attention to and are aware of their present experiences [14]. If we do not pay deliberate attention to our thoughts and feelings, which is a function of the observer self, we will almost automatically act. For example, if you notice a high-calorie food in front of you, you will eat it, or if the TV is on, you will sit down and watch without thinking. The MAAS includes items such as “I snack without being aware that I’m eating.” It is an appropriate scale to measure the mindfulness of diabetes patients. In this study, the Japanese version of MAAS was used [15]. The respondents rated the items on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = almost always to 6 = almost never).

Values

The Values Clarification Questionnaire for Patients with Diabetes (VCQD) is a 15-item instrument that measures progress toward living one’s values [16, 17]. The questionnaire has excellent internal consistency (α = .90) and has criterion-related validity with the Valuing Questionnaires [18, 19] and the Short Form-8 Health Questionnaire (SF-8) [20, 21]. The statistical results were as follows (Valuing Questionnaires Progress: r = .58, Valuing Questionnaires Obstruction: r = −.22, SF-8 physical-related quality of life: r = .30, SF-8 mental-related quality of life: r = .27). In this study, the respondents composed a diabetes-related value description following the instruction given and then rated items on a 7-point Likert scale (0 = not at all true of me to 6 = completely true of me) to answer the questions. The instructions, as well as examples of items, are given in the following. Instructions: Write down why and for what purpose/reason you would alter your lifestyle. Refer to the following questions. What kind of life would you like to live if your disease stopped progressing and your body were as free as you wish? What way of spending your time and energy would make you happiest? Examples: “It is rewarding to take steps in accordance with my values even though I have difficulties” and “I feel vigorous when taking steps in accordance with my values.”

Diabetes self-management

The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure (SDSCA) is a 17-item instrument that measures the frequency of the performance of diabetes self-care over the last 7 days, including diet, exercise, blood glucose testing, foot care, and tobacco use [22]. In this study, the subscales of the Japanese version of SDSCA on diet and exercise were used [23]. The respondents marked the number of days on which the indicated behavior was performed on an 8-point Likert scale (from 0 to 7 days).

Diabetes-specific distress

The Problem Areas in Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (PAID) is a 20-item instrument that measures diabetes-specific distress [24]. In this study, the Japanese version of PAID was used [25]. The respondents rated items on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not a problem for me to 4 = a serious problem for me).

Depressive symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item instrument that measures depressive symptoms in the general population [26]. In this study, the Japanese version of CES-D was used [27]. The respondents rated items on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = rarely or none of the time to 3 = most or all of the time).

Hemoglobin A1c

Patients’ hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels were given as self-reported data. HbA1c is the most common assessment of glycemic control. It reflects average blood glucose over the past 3 months.

Statistical analysis

Single regression analysis, model-based cluster analysis, and one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted in three steps. All analyses were conducted using HAD16_202 [28].

Step 1: Single regression analyses were conducted to examine age, sex, duration of illness, complications, and cessation of treatment as possible predictors of diabetes-related outcomes.

Step 2: Improved k-means cluster analysis was conducted to derive the patterns for acceptance, mindfulness, and values for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Improved k-means cluster analysis was originally developed as an improvement to traditional cluster analyses that allows test and comparisons of the fit of a number of cluster solutions using log likelihood, the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and the Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) as indicators of the relative fit of different cluster solutions. Substantive differences in patterns within the clusters were also considered.

Step 3: After determining the optimal number of clusters, one-way ANCOVA controlling for age, sex, duration of illness, complications, and cessation of treatment found in the preliminary analyses, were conducted to test for differences in diabetes-related outcomes among clusters. Post-hoc tests were conducted using the Holm method, used to control for type I errors. In addition, the index for cohen’s d was calculated in effect size, serving as a standardized indicator unaffected by sample size.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Waseda University Academic Research Ethical Review Committee (2017–227). Informed consent was obtained by all the study participants. The study protocol followed the guidelines for Epidemiological Studies in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Results

In the first step, preliminary single regression analyses were conducted to determine which demographic characteristics were predictive of outcomes. These included the direct effects of age, sex, duration of illness, complications, and cessation of treatment (Table 1). Age predicted SDSCA diet (β = 0.21; p < .01), SDSCA exercise (β = 0.25; p < .01), PAID (β = − 0.19; p < .01), and CES-D (β = − 0.39; p < .01). Sex (female) predicted SDSCA diet (β = 0.18; p < .01). Cessation of treatment (yes) predicted CES-D (β = − 0.19; p < .01). Complications (yes) predicted PAID (β = 0.30; p < .01).

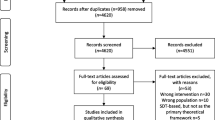

In the second step, improved k-means cluster analysis was conducted to derive the retention patterns for acceptance (AADQ), mindfulness (MAAS), and values (VCQD) for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Three- to six-class models with equal indicator variances were estimated without problems. Using solely fit statistics (log likelihood, BIC, and AIC), as the number of clusters increased and the retention pattern of behavioral processes became more subdivided, the model fit became worse. The three-class model was found to be the statistically preferred model; however, it is also important to consider substantive differences in patterns within clusters. The four-class model provided four characteristic patterns with clearly differentiated values between the clusters (Fig. 1). In contrast, because z-scores of three scales in the three-class model were similar in each cluster, the clusters were merely average, high, and low in all scales without significant information of behavioral processes related to ACT (Fig. 2). In the identification of possible intervention targets, it was considered optimal to determine four distinctly different process patterns. Taking into consideration both fit statistics and process patterns, the freed-variance four-class model was found to be the most appropriate (Table 2). Standardized z-scores were calculated for each measure within each cluster to examine the conceptual differences among clusters. Labels for the clusters were created by examining these differences. Cluster 1 (“Average” N = 66) described patients who had average levels (− 0.50 < z-score < 0.50) of acceptance, mindfulness, and values. Cluster 2 (“Flexibility” N = 59) described patients who exhibited high levels (z-score > 0.50) of acceptance, mindfulness, and values. Cluster 3 (“Values/low” N = 38) described patients who exhibited average levels (− 0.50 < z-score < 0.50) of acceptance and mindfulness and low levels (z-score < − 0.50) of values. Cluster 4 (“Values/high” N = 48) described patients who exhibited average levels (− 0.50 < z-score < 0.50) of acceptance, mindfulness, and high levels (z-score > 0.50) of values. In this study, a z-score higher than 0.50 was defined as “high” and a score lower than − 0.50 as “low”. The mean scores of the AADQ, MAAS, and VCQD in each cluster were as follows. In cluster 1, AADQ 39.20, MAAS 62.33, VCQD 61.55; in cluster 2, AADQ 48.78, MAAS 77.70, VCQ 77.25; in cluster 3, AADQ 40.24, MAAS 64.63, VCQD 42.45; and in cluster 4 AADQ 40.50, MAAS 65.15 and VCQD 83.55.

The third step, a one-way ANCOVA controlling for significant interactions found in the preliminary analyses was conducted to test for cluster differences (Table 3). The ANCOVA for SDSCA diet and exercise did not produce significant results: F (3, 199) = 0.71, p = n.s.; F(3, 203) = 1.46, p = n.s. The ANCOVA for diabetes-specific distress (PAID) showed a significant trend, F(3, 195) = 2.24, p < .10. Using a Bonferroni correction, the results of post-hoc tests revealed that “Average” demonstrated more diabetes-specific distress than “Flexibility” (p < .01, d = 0.90), that “Values/low” demonstrated more diabetes-specific distress than “Flexibility,” (p < .01, d = 0.85) and that “Values/high” demonstrated more diabetes-specific distress than “flexibility” (p < .01, d = 0.68). The ANCOVA for depressive symptoms (CES-D) was significant: F(3, 203) = 3.07, p < .03. Using a Bonferroni correction, the results of post-hoc tests revealed that “Values/low” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Average” (p < .00, d = 0.67), “Average” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Flexibility” (p < .00, d = 1.18), “Values/low” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Flexibility” (p < .00, d = 1.85), and “Values/high” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Flexibility” (p < .01, d = 0.59). “Average” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Values/high” (p < .01, d = 0.59), and “Values/low” demonstrated more depressive symptoms than “Values/high” (p = .00, d = 1.26). The ANCOVA for HbA1c was significant: F(3, 203) = 2.64, p < .05. Using a Bonferroni correction, the results of post-hoc tests showed that “Values/high” demonstrated much higher HbA1c than “Flexibility” (p < .00, d = 0.77).

Discussion

This study investigated empirically derived patterns for acceptance, mindfulness, and values in a sample of Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes as indicators of psychological flexibility to examine the relations among these patterns and diabetes-related outcomes.

Regarding the influence demographic data have on diabetes related outcomes, single regression analysis results indicated that age is related to many diabetes related outcomes. The higher the age is, self-care behaviors such as dietary management and exercise are apt to be continued and depressive symptoms and diabetes related distress to be lower. It is reported that patients in late middle age are troubled by not being able to prioritize their dietary management because of “business relationships”, which includes eating and drinking with business partners [29]. It might be that this studies’ participants tended to experience difficulty in maintaining self-care behaviors, depressive symptoms, and diabetes related distress in their everyday lives because their average age was 58.84; middle-aged patients in their forties to fifties are busy with their work and engage in frequent wining and dining compared with older patients, including retirees in their sixties to seventies.

Also, it is indicated that the onset of diabetes complications is related to diabetes related distress, with patients having diabetes complications expressing stronger diabetes related distress compared with patients with no complications. A survey using PAID (diabetes related distress) given to 653 diabetes outpatients demonstrated that age, female sex, medication (especially insulin treatment), complications, hospitalization, hypoglycemia, and high HbA1c predicted higher PAID scores [30]. Some of these variables were not measured in this study, but similar results were found in terms of lower diabetes-related distress with older age and higher diabetes-related distress in patients with diabetic complications. Improved k-means cluster analysis results identified four clusters, Cluster 1 “Average” (average levels of acceptance, mindfulness, and values), Cluster 2 “Flexibility” (high levels of acceptance, mindfulness, and values), Cluster 3 “Values/low” (average levels of acceptance and mindfulness and a low level of values), and Cluster 4 “Values/high” (average levels of acceptance and mindfulness and a high level of values). Acceptance and mindfulness were at similar levels (z < .05) in Cluster 1 “Average”, Cluster 3 “Values/low”, and Cluster 4 “Values/high”. In other words, these clusters were classified according to the level of values. These results indicate that while a number of patients with only high levels in clarified values exist, there are only few patients showing high levels only in acceptance and mindfulness. In addition, it was also proven that while acceptance and mindfulness had a strong relation, this behavioral process had a weak relation with values clarification. This indicates that the ACT behavioral process is largely divided into the “mindfulness and acceptance process” and the “commitment and behavioral changing process”.

ANCOVA results showed that “Flexibility” had lower diabetes-specific distress and depressive symptoms compared with the other clusters. Thus, increasing flexibility via ACT interventions can improve quality of life among type 2 diabetes patients. However, no main effects of clusters were shown for self-care behaviors, such as diet and exercise. The difficulty in measuring self-care behaviors such as diet and exercise via retrospective questionnaires might be related to this result. Prince et al. (2008) conducted a systematic review of the measurement of physical activity and found that retrospective questionnaires and direct measures (e.g., accelerometers) were not consistent [31]. Measurements using retrospective questionnaires of everyday behaviors such as diet and exercise are susceptible to recall bias and therefore include the probability of undermined ecological validity. SDSCA is a globally used instrument to measure self-care behaviors, but the low relation its results have with glucose control levels has been noted [32, 33]. In diet, the mean for “Flexibility” with the most favorable HbA1c was 26.14, and the mean for “Value/high” with the most unfavorable HbA1c was 24.18, with little difference. Similarly, there was little difference in exercise, with the mean for “Flexibility” being 8.38 and the mean for “Value/high” 8.30. Therefore, little association was shown between diet, exercise in SDSCA and HbA1c (r = −.11, r = − 04). Based on these results, it may be necessary to measure self-care behavior using methods such as Ecological Momentary Assessment that record in real time [34]. For example, calorie intake can be calculated from a food diary using a Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), and exercise intensity (METs; Metabolic Equivalent of Task) can be calculated from physical activity using an accelerometer. These may show a better relation with HbA1c than retrospective questionnaires. Furthermore, the EMA will allow us to examine the true effectiveness of the ACT process. For example, we must examine whether patients with high levels of psychological flexibility tend to accept diabetes-related unpleasant thoughts and emotions occurring before meals, thus leading them to continue their appropriate caloric intake. We must also examine whether patients with high levels of value tend to exercise appropriately according to their own values while having negative thoughts and feelings such as “I am too lazy to move after eating”.

“Average” showed the same level of diabetes-related distress as “Values/low” and “Values/high”. The mean CES-D score for “Average” was 17.73 points; the cutoff for CES-D was 16 points and “Average” was above the cutoff [26]. The reason for this is that 32.4% of diabetic patients have depressive comorbidity, and depression is common among diabetic patients [35]. In Japan, Shumiya et al. measured CES-D in 75 patients who participated in a diabetes class [36]. The results showed that the mean was 15.8 (16.9 for men and 15.1 for women), which is around the cutoff and comparable to the “Average” of this study.

“Values/low” demonstrated greater degrees of depressive symptoms compared with other clusters. The average score of CES-D for Cluster 3 “Values/Low” was 23, far exceeding the cutoff. “Values/high” demonstrated fewer depressive symptoms than “Values/low”. However, diabetes-related distress was similar between “Values/high” and “Values/low” and HbA1c were the worst for “Values/high” among all clusters. This suggests that patients with a pattern of only high levels of value and not high levels of acceptance and mindfulness were not able to face the treatment of diabetes. They live a relatively full life, but their various activities may include many behaviors that worsen their glycemic control. On the other hand, patients with a pattern of low levels of value and not high levels of acceptance and mindfulness may have lower overall activity levels, including behaviors that may worsen glycemic control. This may have resulted in strong depressive symptoms, but not so poor HbA1c.

The importance of values is emphasized in ACT for diabetes patients, but we argue, given our results, that acceptance and mindfulness are very important, at least for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes.

This study indicated that each aspect of the ACT model is necessary for managing diabetes treatment while improving quality of life. However, considering that patients who demonstrate a high level of values only exist in a certain number while patients who demonstrate high levels of only acceptance and mindfulness do not exist, it might be helpful to emphasize acceptance and mindfulness in one-day ACT workshops.

The limitations of this study are as follows. Firstly, because it was carried out by internet survey, items such as sociodemographic information and HbA1c were based on the participant’s self-report. This may be the reason for the low rate of diabetes complications. In addition, many mildly ill patients with relatively good HbA1c were included. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to critically ill patients with poorer HbA1c. Secondly, the subjects of this study were limited to Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is a disease showing wide disparities due to race and environment. For example, the average Japanese type 2 diabetes patient is less obese than the average in Europe and the United States. In further studies, we must extend our research subjects to include people from different areas and of different races. Thirdly, there was limited information on the attributes of the subjects. For example, we considered that employment status was related to the fact that older people were more likely to continue self-care behaviors such as diet control and exercise. However, we did not measure variables related to employment status, which limits our ability to examine this point. Self-care behavior is thought to be related to various attributes of the subjects. In the future, it will be necessary to examine the relation between psychological flexibility and self-care behavior by considering a wider range of subject attributes in addition to age, sex, duration of illness, complications, and treatment status.

Conclusions

The purpose of the present study was to examine the effects of promoting the active component patterns of ACT on Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. The findings of the present study indicate that patients who have “Flexibility” and “Values/high” had lower depressive symptoms. However, “Values/high” demonstrated diabetes-related distress and poor blood-glucose levels. Values is emphasized in ACT for diabetes patients, but this study indicated that acceptance and mindfulness are very important for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. It might be helpful to emphasize acceptance and mindfulness in one-day ACT workshops.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed are not publicly available due to the regulations of the ethics committee.

Abbreviations

- AADQ:

-

The Acceptance and Action Diabetes Questionnaire

- ACT:

-

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criteria

- ANCOVA:

-

Analyses of Covariance

- BIC:

-

Bayesian Information Criteria

- CES-D:

-

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- MAAS:

-

The Mindful Attention Awareness Scale

- PAID:

-

The Problem Areas in Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire

- SDSCA:

-

The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities Measure

- SF-8:

-

The Short Form-8 Health Questionnaire

- VCQD:

-

The Values Clarification Questionnaire for Patients with Diabetes

References

Norris SL, Lau J, Smith SJ, Schmidt CH, Engelgau MM. Self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(7):1159–71. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159.

Fall E, Roche B, Izaute M, Batisse M, Tauveron I, Chakroun N. A brief psychological intervention to improve adherence in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):432–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.003.

Dindo L. One-day acceptance and commitment training workshops in medical populations. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;2:38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.018.

Sheppard SC, Forsyth JP, Hickling EJ, Bianchi J. A novel application of acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosocial problems associated with multi sclerosis results from a half-day workshop intervention. Int J MS Care. 2010;12(4):200–6. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073-12.4.200.

Dindo L, Recober A, Marchman J, Turvey C, O’Hara MW. One-day behavioral treatment for patients with comorbid depression and migraine: a pilot study. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(9):537–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.007.

Dindo L, Recober A, Marchman J, O’Hara MW, Turvey C. One-day behavioral intervention in depressed migraine patients: effects on headache. Headache. 2014;54(3):528–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12258.

Lillis J, Hayes SC, Bunting K, Masuda A. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: a preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37(1):58–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9083-x.

Dindo L, Marchman J, Gindes H, Fiedorowicz JG. A brief behavioral intervention targeting mental health risk factors for vascular disease: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(3):183–5. https://doi.org/10.1159/000371495.

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy, second edition: the process and practice of mindful change. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, Glenn-Lawson JL. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Pyschol. 2007;75(2):336–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.336.

Pekarik G, Wierzbicki M. The relationship between clients' expected and actual treatment duration. Psychother Theor Res Pract Train. 1986;23(4):532–4. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085653.

Wierzbicki M, Pekarik G. A meta-analysis of psychotherapy dropout. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 1993;24(2):190–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.24.2.190.

Saito J, Shoji W, Kumano H. The reliability and validity for Japanese type 2 diabetes patients of the Japanese version of the acceptance and action diabetes questionnaire. Biopsychosoc Med. 2018;12(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-018-0129-9.

Brown KW, Ryan RM. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84(4):822–48. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822.

Fujino M, Kajimura S, Nomura M. Development and validation of the Japanese version of the mindful attention awareness scale using item response theory analysis. Jpn J Pers. 2015;24(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.2132/personality.24.61.

Saito J, Yanagihara M, Shima T, Iwata A, Honda H, Ouchi Y, et al. Development of the values clarification questionnaire and confirmation of its reliability and validity. Jpn J Behav Ther. 2017;43:15–26.

Saito J. Optimization of a psycho-behavioral approach to type 2 diabetes using ecological momentary assessment [dissertation]. Saitama (JPN): Waseda University; 2019.

Smout M, Davies M, Burns N, Christie A. Development of the valuing questionnaire (VQ). J Contextual Behav Sci. 2013;3(3):164–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.001.

Doi S, Sakano A, Muto T, Sakano Y. Reliability and validity of a Japanese version of the valuing questionnaire (VQ). Jpn J Behav Ther. 2017;43:83–94.

Ware JE, Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8 health survey. Lincoeln RI: Quality Metric Incorporated; 2001.

Fukuhara S, Suzukamo Y. Manual of the SF-8 Japanese version. Institute for Health Outcomes and Process Evaluation Research: Kyoto; 2004.

Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):943–50. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.7.943.

Daitoku M, Honda I, Okumiya A, Yamasaki Y. Validity and reliability of the japanese translated "the summary of diabetes self-care activities measure". J Jpn Diabetes Soc. 2006;49:1–9.

Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(6):754–60. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.18.6.754.

Ishii H, Welch G, Jacobson A, Goto M, Okazaki K, Yamamoto T. The Japanese version of problem area in diabetes scale: a clinical and research tool for the assessment of emotional functioning among diabetic patients. Diabetes. 1999;48:1397.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T, Asai M. A new self-report depression scale. Psychiatry. 1985;27:717–23.

Shimizu H. An introduction to the statistical free software HAD: suggestions to improve teaching, learning and practice data analysis. J Media Inf Commun. 2016;1:59–73.

Yasuda K, Matsuoka M, Fujita K, Koga A, Sato K. Difficulties for relationships in diabetic self-management: coping behaviors enabling change from difficult feelings to positive feelings. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2005;25(2):28–36. https://doi.org/10.5630/jans1981.25.2_28.

Fujii H, Karube N, Tokunaga R, Hakogi M, Nakama K, Hayashi M, et al. Clinical usefulness of “problem areas in diabetes survey (PAID)”. J Jpn Diab Soc. 2008;51:497–505.

Prince SA, Adamo KB, Hamel ME, Hardt J, Gorber SC, Tremblay M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-5-56.

Kamradt M, Bozorgmehr K, Krisam J, Freund T, Kiel M, Qreini M, et al. Assessing self-management in patients with diabetes mellitus type 2 in Germany: validation of a German version of the summary of diabetes self-care activities measure (SDSCA-G). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2014;12(1):185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-014-0185-1.

Mayberry LS, Gonzalez JS, Wallston KA, Kripalani S, Osborn CY. The ARMS-D out performs the SDSCA, but both are reliable, valid, and predict glycemic control. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;102(2):96–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2013.09.010.

Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2008;4(1):1–32. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415.

Gavard JA, Lustman PJ, Clouse RE. Prevalence of depression in adults with diabetes: an epidemiological evaluation. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(8):1167–78. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.16.8.1167.

Shumiya T, Kunimasa Y, Hishikawa C, Fujii M, Oba Y, Sawada C, et al. Usefulness of psychological testing in diabetic education. J Rural Med. 2003;52(4):726–32. https://doi.org/10.2185/jjrm.52.726.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by a Research Fellowship of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science for Young Scientists for the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JS and HK developed the study design. JS collected the data, performed the statistical analysis, drafted the article in whole. HK made critical revisions to the article. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Waseda University Academic Research Ethical Review Committee (2017–227). Informed consent was obtained by all the study participants. The study protocol followed the guidelines for Epidemiological Studies in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, J., Kumano, H. The patterns of acceptance, mindfulness, and values for Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a web-based survey. BioPsychoSocial Med 16, 6 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-022-00236-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13030-022-00236-3