Abstract

Introduction

Nursing students experienced various types of bullying and abuse in their practice areas. This study aims to assess the incidence, nature, and types of bullying and harassment experienced by Jordanian nursing students in clinical areas.

Methodology

A cross-sectional, descriptive design was used, utilizing a self-report questionnaire. A convenient sampling technique was used to approach nursing students who are in their 3rd or 4th year in governmental and private universities.

Results

Of 162 (70%) students who reported harassment, more than 80% of them were females and single. Almost 40% of them reported that males were the gender of the perpetrator. Almost 26.5% of them reported that patient’s relatives or friends were the sources of harassment. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment (79%). Findings showed that there was a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on gender and type of the university. Also, there were significant negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life.

Conclusion

Harassment in the clinical area is affecting the professional and personal lives of students, who lack the knowledge of policy to report this harassment.

Key messages

1. Most of the students who reported harassment were females and single.

2. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment.

3. Psychological/verbal harassment affected the students’ professional and personal achievements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The healthcare sector is one of the most subjected sectors to violence among all sectors. Between 8 and 38% of healthcare providers exposed to workplace violence (WPV) in their career [1]. Nationally, the chief of the Jordan Medical Association declared that about 10 attacks on healthcare workers are recorded every month [2]. Among all healthcare workers, nurses and physicians are the most vulnerable personnel to WPV [3, 4], as nurses have more contact with patients and their families or relatives.

Not only nurses are susceptible to WPV, but nursing students also are subjected to various types of violence, bullying, and harassment in their practice areas [5,6,7,8,9]. The prevalence of bullying among nursing students varies based on many factors. There were significant variations in the prevalence of bullying among nursing students, ranging from 9 to 96%, according to an integrative literature review that included 30 articles and examined the issue in addition to other factors [10]. In Australia, a study reported that half of 888 nursing students experienced bullying in the last year [6]. Similarly, an Omani study found that 53.4% of 118 nursing students experienced at least one incident of bullying during their practice period [5].

Nursing students experienced various types of bullying and abuse in their practice areas including verbal, emotional, physical, sexual, and racial abuse [5, 8, 11,12,13,14]. The most common form of abuse nursing students experienced was verbal abuse [6, 8, 12]. Students are mostly bullied by other nursing or medical students, nurses, physicians, other healthcare teams, school faculty, or their instructor [15], patients or their families [6, 8, 11, 12], other hospital workers [6].

All forms of bullying and harassment have negative consequences on students, personally, physically, and emotionally; they might feel anxiety [12, 16,17,18], sickness, low self-esteem [12, 17, 18], anger [12, 17, 19], fear, depression [12, 15, 19]. Additionally, bullying and harassment have an impact on students’ performance; they may cause them to be hesitant to visit clinical areas, doubt the quality of care they provide because it undermines their confidence, or reconsider their careers as nurses [5, 6, 12, 15, 19].

With all the negative consequences of bullying, most nursing students don’t report the incidents of bullying they have experienced [6, 11, 13, 20]. Many students consider it to be part of the nursing profession [6, 11], i.e. the “normalization” of bullying and violence [13]. Other students hated to be seen as victims [6], and others think that even if they reported the harassment, no action would be taken [6, 20].

There is little known about nursing students’ experience, consequences, and reporting of bullying and harassment. Based on the literature review, there are many Jordanian studies on violence against nurses, but there is no published study investigating nursing students’ experience of bullying and harassment in Jordan, [21]. This study aims to assess the incidence, nature, and types of bullying and harassment experienced by Jordanian nursing students in clinical areas.

Materials and methods

Design

Utilizing a self-report questionnaire, a cross-sectional, descriptive design was used, as very little is known about bullying and harassment of nursing students in Jordan.

Settings

The study was conducted at Nursing Faculties in five governmental and five private universities. Governmental universities are located in the north, middle, and south of Jordan. Four of them have the largest number of nursing students among all governmental and private universities. Three private universities are located in the Capital and two are in the north of Jordan. There are very few private universities outside the Capital. Approached private universities have the largest number of nursing students among all private universities.

Sample

Non probability, convenient sampling technique was used. We approached nursing students who met the inclusion criteria: who were in their 3rd or 4th year of study and willing to participate. The sample size was determined based on Cohen power primer [22]. Using a conventional power of 0.8, medium effect size of 0.25, level of significance of 0.05, and Pearson Correlation, the minimum sample size would be 134. Using G-power 3.1.9.2, and using the power of 0.8, medium effect size (0.25), and level of significance of 0.05 and Pearson r, the minimum total sample size would be 138 [23].

Study Tool

The questionnaire in the current study was adapted from Hewett [24]. The questionnaire consists of six parts, including (a) demographic (including Age, Gender, Marital Status, and Wearing Hijab for females) and educational data (including Year of Study, Type of Program, and University type), (b) verbal (12 items), physical (8 items), and sexual harassment (6 items) in clinical areas, (c) data about the perpetrator (12 items) and the settings (3 items) where the harassment occurred, (d) impact of harassment on personal life (8 items) and professional achievement (5 items), (e) reporting of harassment in clinical areas (one question about if the student reported the harassment or not and 6 items about the reason behind not-reporting the incident), and (f) management of violence in clinical areas (one open-ended question). The tool consists of 67 items; each item rated the occurrence of harassment or the impact of harassment on a four-point Likert scale (0 ―Never to 3 – Often: more than 5 times). Items about reporting the harassment were yes or no questions. The internal consistency of the questionnaire revealed Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. Originally, the tool was developed in English. It was translated in compliance with WHO translation guidelines [25]. Community health and mental health nursing professionals evaluated the questionnaire after it had been translated and before the pilot study was carried out to ensure the study instruments’ content validity. The research process - from distributing questionnaires to receiving data - was tested, and no problems were found.

Data collection

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Applied Science Private University’ committees, the principal investigator approached the deans of Nursing Faculties and explained the study’s purpose and procedure. Then, a poster about the study with a barcode of the online questionnaire was displayed in the hall of all nursing faculties. The participant read the cover letter before filling out the questionnaire, which explained the purpose of the study, the role of the participants, their right to withdraw from the study, and all their information would be anonymous and confidential.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approvals from the Applied Science Private University as well as from all other participating universities were obtained before commencing the research. Besides, this research was conducted under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 25). The study sample and their responses were described using descriptive statistics. Differences in participants’ scores based on their characteristics were assessed by running a series of t-tests. Further, Pearson coefficient was used to detect relationships between the participants’ characteristics and harassment scores.

Results

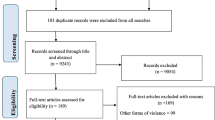

In this study, 268 nursing students were approached, 244 consented and 230 of them fully completed and returned the questionnaires; those were involved in the final analysis. All nursing students involved in this study have attended at least one clinical placement course and were either in their third or fourth year of study. Data was divided into two groups (i.e. group one: students who reported facing harassment; and group two: students who did not report any type of harassment).

Description of the participants

Table 1 shows the characteristics of nursing students based on the occurrence of harassment. Concerning the total participated nursing students (the two groups), approximately, 70% (N = 162) of them reported that they faced harassment. Female students formed almost 80% of the overall sample. Most of the students were single with a mean age of 22.37 ± 3.156. Participated students were enrolled in the university either in the regular program or bridging program with almost half of the students from governmental universities and half of them from private universities.

Regarding the group of students who reported harassment (i.e. group one), more than 80% (N = 182) of them were females and single. Almost 40% (N = 65) of them reported that males were the gender of the perpetrator. Nursing students were asked about the source of harassment and almost 20% (N = 33) of them showed that doctors were the sources of harassment, 17.9% (N = 29) reported that patients were the source of harassment, 37.7% (N = 61) were patients relatives or friends and 19.8% (N = 32) administrative staff were the source of harassment. Almost two-thirds 66% (N = 107) of those who stated they were harassed didn’t know about the policy of reporting harassment. Psychological/verbal harassment was the most reported type of harassment, representing approximately 79% (N = 142) of those reported harassment.

The difference in harassment based on the characteristics of the participants

Several independent sample t-tests were conducted to examine the difference in psychological/verbal harassment; physical harassment, and sexual harassment based on the gender of the student, marital status, type of the university, type of the program, and previous work experience. These statistical tests were only conducted for students who reported the occurrence of harassment (group one). Findings showed that there were no statistical differences in physical and sexual harassment based on all previous variables.

About psychological/verbal harassment, Table 2 shows that there was a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on gender and type of the university. Female students reported significantly higher levels of psychological/verbal harassment (M = 22.14, SD = 7.29) than male students (M = 19.31, SD = 4.74); t (60.976) = -2.61, p-value 0.011. Eta squared was 0.04 indicating that the magnitude of the difference was small. Moreover, students from private universities reported significantly higher levels of psychological/verbal harassment (M = 22.60, SD = 7.06) than those from governmental universities (M = 20.42, SD = 6.73); t (155.086) = -2.008, p-value 0.046. Eta squared was 0.024 indicating that the magnitude of the difference was small. There were no statistical differences in psychological/verbal harassment based on marital status, type of the program, and previous work experience.

The correlation between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, personal life, and age of nursing students

Pearson r product-moment correlation coefficient was used to examine the relationship between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, personal life, and age of nursing students. Table 3 shows that there were statistically significant moderate negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life (r=-0.437, p-value < 0.001; r=-0.566, p-value < 0.001, respectively). An increase in psychological/verbal harassment was significantly associated with a decrease in the professional achievement and personal life of the students. The R-squared between psychological/verbal harassment, and professional achievement is 0.19 indicating that almost 19% of the change in the variance of professional achievement is explained by psychological/verbal harassment. Again, the R-squared between psychological/verbal harassment and personal life is 0.32 indicating that almost 32% of the change in the variance of personal life is explained by psychological/verbal harassment. However, findings showed that there was no significant correlation between age and psychological/verbal harassment.

Discussion

Nursing students spend around 20 h weekly in the clinical area after the first year. They are on the first line of encounter not only with patients and their relatives, but also with nurses, physicians, and other health team members. The study reveals that 70% (n = 162) of students in the sample were subjected to one or more types of harassment, which is considered a little bit lower than what was reported by Abd El Rahman and Mabrouk [17] who conducted their research in Egypt found that (88%) of the sample faced bullying during their clinical rotation. On the other hand, this result is higher than the Omani study which found that 53.4% of students experienced harassment at least once throughout their clinical rotation [5]. Also, it was higher than what was reported by Birks and colleagues; who compared Australian and British students and found that (50.1%) and (35.5%) respectively, were bullied among students in their sample [26]. Additionally, it was higher than a New Zealand study which revealed that 40% of students experienced harassment in clinical areas [16]. A higher percentage of bullying among nursing students could be attributed to underestimating student’s knowledge, skills, and experiences.

The study revealed that most of the bullied students (80%) were females. This is not strange as the majority of the sample were female too. These results are comparable with an Omani study [27]. However, a study found that Australian females were subjected to harassment more than male students, while this was not the case for British students [26]. Over the world, the nursing profession is considered a female profession; this could be the case because females are more compassionate and capable to care of people in health and sickness.

The study revealed that 40% of the reported gender of perpetrators were males. This was inconsistent with what was found by Palaz, who found that the majority of perpetrators were females (92.4%) [28]. Whereas, the perpetrators in the current study were 26.5% patient’s relatives or friends, 20% doctors, 18% patients, and 13.9% administrative staff. Omani study found that patients (42.3%) and their relatives (33.9%) were the major perpetrators, followed by other healthcare teams (31.4%), doctors (28%), and registered nurses (26%) [5]. Whereas, the key perpetrators of verbal abuse in Hong Kong were patients (66.8%), followed by hospital staff (29.7%), university supervisors (13.4%), and patients’ relatives (13.2%) [29]. The students have to contact with different individuals with varying educational backgrounds, cultural backgrounds, ethical perspectives, and value systems. However, many students have low self-esteem and limited communication skills, especially in clinical settings, as they are considered new and stressful areas [5].

Despite the large number of harassed nursing students, two-thirds of them don’t know about reporting harassment policy (66%). This was very close to a study conducted in Oman that found victims of harassment were unaware of any regulations against harassment in in college (60.2%) or clinical areas (65.2%) [11]. On the other hand, 36% of students in the current study reported that they didn’t report any incident as nothing would be done. Budden and colleagues reported that many participants knew about such policies, whether in the university (65.5%) or clinical settings (69%). Despite students’ knowledge of policies, these were not clear, they feared being mistreated, thought that nothing would be done if reported, didn’t know how and where to report, thought that the incidence was not significant to report [6], and the most frightening idea is that harassment is considered a normal part of the job [6, 11, 26].

The current study revealed that most students 79% reported subjecting to psychological/verbal harassment. This result supports the previous studies conducted worldwide; such as 60% in Turkey [28], 73.3% in Iran [30], and 55% in Saudi Arabia [31]. Although a smaller percentage was reported for verbal harassment in Hong Kong (30.6%), it was higher than that for physical abuse (16.5%) [29]. Nursing students weren’t subject to physical harassment, they were subjected to psychological/verbal harassment or sexual harassment as gestures without reaching the point of physical harassment. Also, the perpetrator is subjected more to legal liability for this type of harassment.

Sexual harassment was reported only in 2.5% of nursing students in the current study, this result was less than what was reported by Tollstern and colleagues, who found that 9.6% of respondents training at a local hospital in Tanzania reported subjecting to sexual harassment [32]. Also, the results of a Chinese meta-analysis revealed that the incidence of sexual harassment among female nursing students was 7.2% [33]. On the other hand, a shocking high result of sexual harassment was reported in Korea, where it was found that 50.8% of the participants faced sexual harassment. The sexual harassment was reported as gender-linked harassment; as 98% of perpetrators were male [34]. Closing one’s way, touching one’s body on purpose, and attempting to have sex, all these fluctuating behaviors in reported sexual harassment might be related to cultural, religious, and behavioral differences between countries [32]. Furthermore, an integrative review revealed that sexual harassment among nursing students is exacerbated by near body contact care role of nursing, the perceptions of societies toward nursing as a women’s profession, the sexualization of nurses, and the imbalances in the workplace [35]. In our society, we are governed by customs and traditions emanating from our Islamic religion. Therefore, compared to other studies, the frequency of sexual harassment in the current study is considered very low.

Although our finding revealed no statistical differences in sexual harassment based on all variables in the study including gender, this could be connected to the low incidence of sexual harassment in the current study. However, the systematic review and other studies worldwide revealed that female nurses are facing a high prevalence of sexual harassment [35,36,37].

On the contrary to what was reported by Budden and colleagues and Cheung and colleagues, our results revealed a statistically significant difference in psychological/verbal harassment based on the gender and type of the university [6, 29]. This could be related to the fact that the sample consisted primarily of female students. Students at private universities reported much higher levels of verbal and psychological harassment than those at governmental universities. These governmental universities are located in areas considered conservative compared to those where private universities are located.

The current study found significant moderate negative correlations between psychological/verbal harassment, professional achievement, and personal life. Professional achievement and personal life tend to decrease as verbal harassment increases. These results are not surprising and are supported by what was found in a Chinese study, which reported a significant increase in sick leave taken after verbal abuse that lasted to ten days. Furthermore, the researchers revealed the presence of a significant negative effect of verbal harassment on personal feelings, clinical performances, and the extent to which they were disturbed by verbal harassment [29]. In the same context, Amoo and colleagues revealed that bullying caused a loss of confidence and the occurrence of stress and anxiety among nursing students [7].

Implications

The current study showed that most of the students who were subjected to harassment didn’t know that there was a policy that addressed this problem. Nursing faculty, health organizational administration, and nursing instructors are responsible for implementing strategies that will end the sequence of all types of harassment and promote a healthy work environment through; improving students’ communication skills, empowering them, establishing and planning goal-directed training programs related to harassment and harassment prevention in clinical area for nursing students before starting their training. Also, it is very important to teach students that harassment should never be tolerated, no matter how it manifests or where it comes from.

The nursing curriculum must be updated to add new topics such as communication skills, and how to deal with perpetrators of different types of harassment. Moreover, the clinical area must have clear policies regarding reporting harassment which should be declared to students. Furthermore, studies are needed regarding the psychological effects of harassment, and how to deal with the psychological effects, to help student manage their fears and negative feelings related to harassment. The literature indicated that many nurses quit or change careers as a result of harassment, so it’s critical to focus on adapting to a zero-harassment environment [38, 39].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include recruiting samples from all geographical areas in Jordan; north, middle, and south, and from governmental and private universities. Despite the strengths of this study, its results should be considering its limitations. There were not enough male students in the sample; further study may adequately recruit male students. Another limitation is not including nationality in the questionnaire, so generalization to all Arabic or other students might be limited. Therefore, it is recommended to replicate this study among various Arabic populations.

Conclusion

This study indicates that harassment is a significant issue among Jordanian nursing students. Nursing students face different types of harassment all over the journey of clinical training. Results showed a high prevalence of psychological/ verbal abuse that affected the professional and personal lives of students. Despite the high incidence of harassment among nursing students, most students have not reported the harassment officially as they lack the knowledge of how to report this harassment or are not aware of the presence of policies regarding harassment, highlighting the importance of providing education to increase their awareness about such policies. The study highlights the role of universities in developing training programs and policies, if none, to prevent harassment in clinical areas and manage the effect of harassment among students. This will contribute in creating a safe, healthy, and supportive educational environment for nursing students.

Data availability

Data cannot be shared openly but are available on request from authors.

References

WHO. Preventing violence against health workers: World Health Organization. 2022. https://www.who.int/activities/preventing-violence-against-health-workers.

Why Physicians. and Nurses are Attacked? Jordan News. 2022.

Bernardes MLG, Karino ME, Martins JT, Okubo CVC, Galdino MJQ, Moreira AAO. Workplace violence among nursing professionals. Revista Brasileira De Med do Trabalho. 2020;18(3):250.

Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, Li L, Dwyer R, Lu K, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(12):927–37.

Qutishat MG, Kannekanti S. Bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students in clinical settings, and its implication to academic strategies and interventions. J Health Sci Nurs. 2019;4(9):56–62.

Budden LM, Birks M, Cant R, Bagley T, Park T. Australian nursing students’ experience of bullying and/or harassment during clinical placement. Collegian. 2017;24(2):125–33.

Amoo SA, Menlah A, Garti I, Appiah EO. Bullying in the clinical setting: lived experiences of nursing students in the Central Region of Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9):e0257620.

Samadzadeh S, Aghamohammadi M. Violence against nursing students in the workplace: an Iranian experience. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2018;15(1).

Jafarian-Amiri SR, Zabihi A, Qalehsari MQ. The challenges of supporting nursing students in clinical education. J Educ Health Promotion. 2020;9:216.

Fernández-Gutiérrez L, Mosteiro‐Díaz MP. Bullying in nursing students: a integrative literature review. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(4):821–33.

Qutishat MG. Underreporting bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students: a descriptive correlation study. Int J Mental Health Psychiatry. 2019;5(1).

Özcan NK, Bilgin H, Tülek Z, BOYACIOĞLU NE. Nursing Students’ Experiences of Violence: A Questionnaire Survey. J Psychiatric Nursing/Psikiyatri Hemsireleri Dernegi. 2014;5(1).

Hallett N, Wagstaff C, Barlow T. Nursing students’ experiences of violence and aggression: a mixed-methods study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;105:105024.

Ehsani M, Farzi S, Farzi F, Babaei S, Heidari Z, Mohammadi F. Nursing students and faculty perception of academic incivility: a descriptive qualitative study. J Educ Health Promotion. 2023;12(1):44.

Baraz S, Memarian R, Vanaki Z. Learning challenges of nursing students in clinical environments: a qualitative study in Iran. J Educ Health Promotion. 2015;4(1):52.

Minton C, Birks M, Cant R, Budden LM. New Zealand nursing students’ experience of bullying/harassment while on clinical placement: a cross-sectional survey. Collegian. 2018;25(6):583–9.

Abd El Rahman RM. Perception of student nurses’ bullying behaviors and coping strategies used in clinical settings. 2014.

Birks M, Budden LM, Biedermann N, Park T, Chapman Y. A ‘rite of passage?’: bullying experiences of nursing students in Australia. Collegian. 2018;25(1):45–50.

Hashim N, Aziz HAM, Amran MAA, Azmi ZN. Bullying among nursing students in UiTM Puncak Alam during Clinical Placement. Environment-Behaviour Proc J. 2020;5(15):49–55.

Albakoor FA, El-Gueneidy MM, El-Fouly OM. Relationship between coping strategies, bullying behaviors and nursing students’ self esteem. Alexandria Sci Nurs J. 2020;22(1):47–58.

Jordanian Database for Nursing Research Jordan: School of Nursing, The University of Jordan. 2017. http://jdnr.ju.edu.jo/home.aspx.

Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155.

Faul F. G*Power. 3.1.9.2 ed. Germany2014. p. Statistical Power Analysis Program.

Hewett D. Workplace violence targeting student nurses in the clinical areas: Stellenbosch. University of Stellenbosch; 2010.

WHO. Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Birks M, Cant RP, Budden LM, Russell-Westhead M, Özçetin YSÜ, Tee S. Uncovering degrees of workplace bullying: a comparison of baccalaureate nursing students’ experiences during clinical placement in Australia and the UK. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;25:14–21.

Qutishat MEGM. Bullying and harassment perceived by undergraduate nursing students in clinical settings and its implication to academic strategies and interventions. J Health Sci Nurs. 2019;9(4).

Palaz S. Turkish nursing students’ perceptions and experiences of bullying behavior in nursing education. J Nurs Educ Pract. 2013;3(1):23.

Cheung K, Ching SS, Cheng SHN, Ho SSM. Prevalence and impact of clinical violence towards nursing students in Hong Kong: a cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2019;9(5):e027385.

Samadzadeh S, Aghamohammadi M. Violence against nursing students in the workplace: an Iranian experience. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2018;15(1):20160058.

Shdaifat EA, AlAmer MM, Jamama AA. Verbal abuse and psychological disorders among nursing student interns in KSA. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2020;15(1):66–74.

Tollstern Landin T, Melin T, Mark Kimaka V, Hallberg D, Kidayi P, Machange R, et al. Sexual harassment in clinical Practice—A cross-sectional study among nurses and nursing students in Sub-saharan Africa. SAGE Open Nurs. 2020;6:2377960820963764.

Zeng LN, Zong QQ, Zhang JW, Lu L, An FR, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of sexual harassment of nurses and nursing students in China: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15(4):749–56.

Kim TI, Kwon YJ, Kim MJ. Experience and perception of sexual harassment during the clinical practice and self-esteem among nursing students. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2017;23(1):21–32.

Smith E, Gullick J, Perez D, Einboden R. A peek behind the curtain: an integrative review of sexual harassment of nursing students on clinical placement. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(5–6):666–87.

Kahsay WG, Negarandeh R, Dehghan Nayeri N, Hasanpour M. Sexual harassment against female nurses: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2020;19(1):58.

Maghraby RA, Elgibaly O, El-Gazzar AF. Workplace sexual harassment among nurses of a university hospital in Egypt. Sex Reproductive Healthcare: Official J Swed Association Midwives. 2020;25:100519.

Yeh T-F, Chang Y-C, Feng W-H, sclerosis, Yang M. C-C. Effect of Workplace Violence on Turnover Intention: The Mediating Roles of Job Control, Psychological Demands, and Social Support. INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing. 2020;57:0046958020969313.

Hollowell A. Violence affects nursing recruitment, retention, NNU report finds. USA: National Nurses United; 2024.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Applied Science Private University for supporting this study. Also, the authors thank the participants and the deans of the nursing faculties.

Funding

Not Applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concepts: A.M. & R.M Design: A.M. & R.M Definition of intellectual content: A.M. & R.M Literature search: A.M. & R.R. Data acquisition: A.M. & R.M Data analysis: A.M. & R.M Statistical analysis: R.M. Manuscript preparation: A.M. & A.S Manuscript editing: A.M. & A.S Manuscript review: A.M. & A.S & R.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval was obtained from the IRB committee in Applied Science Private University (2021-2022-5-1). The principal investigator posted a poster about the study with a barcode of the online questionnaire in the hall of all nursing faculties. The participant read the cover letter before filling out the questionnaire, which explained the purpose of the study, the role of the participants, their right to withdraw from the study, and all their information would be anonymous and confidential. Filling out the questionnaire was considered as a consent form. So, informed consent was obtained implicitly from all subjects.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable (as explained before).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masadeh, A., Al-Rimawi, R., Salem, A. et al. Jordanian nursing students’ experience of harassment in clinical care settings. BMC Nurs 23, 587 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02146-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02146-x