Abstract

Background

Studies have reported frailty as an independent risk factor of mortality in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). However, no systematic review and meta-analysis has been conducted to determine the relationship of frailty and IBD. We aimed to investigate the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD and the impact of frailty on the clinical prognosis of these patients.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Ovid (Medline), Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library from database inception until October 2022. This systematic review included observational studies describing IBD and frailty. We performed meta-analysis for the frailty prevalence in patients with IBD. We analyzed primary outcomes (mortality) and secondary outcomes (infections, hospitalizations, readmission, and IBD-related surgery).

Results

Nine studies with a total of 1,495,695 participants were included in our meta-analysis. The prevalence of frailty was 18% in patients with IBD. The combined effect analysis showed that frail patients with IBD had a higher risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio = 2.25, 95% confidence interval: 1.11–4.55) than non-frail patients with IBD. The hazard ratio for infections (HR = 1.23, 0.94–1.60), hospitalizations (HR = 1.72, 0.88–3.36), readmission (HR = 1.21, 1.17–1.25) and IBD-related surgery (HR = 0.78, 0.66–0.91) in frail patients with IBD.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that frailty is a significant independent predictor of mortality in patients with IBD. Our work supports the importance of implementing frailty screening upon admission in patients with IBD. More prospective studies are needed to investigate the influence of frailty on patients with IBD and improve the poor prognosis of patients with frailty and IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Frailty refers to a clinically identifiable state of increasing vulnerability in older adults. Sarcopenia is defined by low muscle strength and low muscle quantity or quality. Age-related declines in function and physiological reserves of multiple organ systems can lead to frailty [1]. Frailty may occur in patients of any age but is more common in elderly patients [2]. Frailty is common in community and clinical settings and can predict many various adverse health outcomes, including mortality [3], disability [4], worsening mobility [5], loneliness [6], falls [7], fractures [8], hospitalization [8], lower quality of life [9], depression [10], dementia [11], cognitive decline [12], and nursing home admission [13]. The connection between mortality and frailty has been verified in many studies and involves many settings and sub-populations [14,15,16].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic systemic inflammatory condition and includes ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn disease (CD), and indeterminate colitis. IBD can cause various symptoms, such as diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, nausea, vomiting, and joint pain [17]. Between 1990 and 2017, the number of individuals with IBD rose from 3.7 million to over 6.8 million, and the global prevalence of IBD increased by 85.1% [18]. The burden of IBD in elderly individuals is increasing with population aging [19]. Approximately 25%–35% of individuals with IBD are over age 60 years [20, 21]. In this age group, the incidence rates of UC are almost universally higher than the rates of CD. The incidence rates of UC range from 1.8 to 20 per 100,000 in the United States and Europe; the incidence rates in the Asia–Pacific region are much lower. The incidence rates of CD range from 1–10 per 100,000 in Europe and more than 50 per 100,000 in New Zealand; the incidence of CD is much lower in the rest of the Asia–Pacific region [22].

Population-based studies indicate that mortality is higher among patients with IBD than among the general population [23, 24]. Thus, it is important to identify the mediators of IBD risk. One study demonstrated that frailty was more prevalent in approximately one-third of hospitalized adults with IBD [25]. Frailty is a substantial physiologic driver of IBD outcomes, including therapy-related infection complications, death, and hospital readmission, according to certain studies [26,27,28]. However, no in-depth analysis has been conducted regarding whether frailty in patients with IBD and all-cause mortality are related. We therefore carried out this systematic review and meta-analysis to investigate how frailty affects outcomes of patients with IBD.

Method

We followed the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guideline in this systemic review [29].

Search strategy

We comprehensively searched several databases and websites, including PubMed, Cochrane, Medline (via Ovid), Embase (via Ovid), and Web of Science, from inception of each database to July 28, 2021. We conducted an updated search in October 2022. Our search strategy included suitable Medical Subject Headings (Mesh) and free-texts words to identify frailty and IBD; the detailed search strategy and search terms can be found in the supplement. We also manually searched the reference lists of all identified studies.

Study selection

Two researchers independently screened all titles and abstracts to confirm the eligibility of relevant studies. Next, the full texts of studies warranting further investigation were assessed independently by two researchers. We resolved all disagreements in discussion with a third researcher until consensus was reached. We used the following inclusion criteria for studies: (1) the study population was mainly patients with IBD; (2) frailty was a risk factor; (3) the prevalence of frailty in the study population was recorded; (4) data on clinical outcomes of frailty in patients with IBD were available in the included studies; (5) the original research was observational research. We excluded the following studies: (1) studies that did not have a cohort of patients with IBD grouped according to frailty and non-frailty; (2) no data on patients with IBD were reported separately in the study; (3) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), reviews, and conference abstracts.

Data extraction

Two researchers independently extracted and reviewed the data. We collected the following information for each study: author, country, study design, percentage of men, mean age, sample size, frailty criteria, assessment of frailty, type of IBD, follow-up period (cohort studies only), primary outcome (mortality), secondary outcomes (infections, hospitalizations, readmission, and IBD-related surgery), and prevalence of frailty.

Assessment of quality

We used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to evaluate the quality of the included studies. The NOS is a nine-point scale with three domains. Four points were allocated for study population selection, two points for comparability, and three points for outcome. We considered studies with NOS ≥ 8 to be of high quality. The comparability score depends on the relevant confounding factors that are corrected. One point was obtained if only correcting confounding factors affecting the outcome or only correcting other critical confounding factors. If both are corrected, two points were given; no score was given if neither is corrected. Two independent investigators discussed any disagreement in the quality assessment.

Statistical analysis

We performed a meta-analysis for the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD using Stata 12 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). According to the heterogeneity of relevant studies, we selected corresponding effects models. We used the chi-squared test and the I2 statistic to identify heterogeneity [30]. When the former test had a value of p ≤ 0.05 and the latter a value of I2 ≥ 50%, this indicated significant heterogeneity. We used a forest plot to estimate the effect size and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Because the content in data extraction can lead to heterogeneity, we used meta-regression to calculate more reliable combined statistics and analyzed the sources of heterogeneity after subgroup analysis. We conducted sensitivity analyses after removing studies that did not report effect size in the meta-analysis of clinical outcome for patients with IBD. We used Egger’s test and Begg’s test to assess publication bias (p < 0.05) by visually inspecting the funnel plots [31, 32]. Additionally, we used the trim-and-fill method to explain publication bias.

Results

Study selection

In our initial search (July 2021), we identified 799 articles in PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, Medline, and Web of Science (Fig. 1). Of these, we excluded 402 duplicate articles and 56 ineligible publications (nine comments, 18 reviews, seven animal studies, two conferences, two non-English studies, six case reports, six guidelines, and six RCTs). We checked the title and abstract of each remaining article in preliminary screening according to the established criteria, and identified 31 publications related to the research topic. Among them, 12 were excluded owing to unavailability of the complete text, 11 of the 19 articles with full text were excluded after reading the entire text in detail, according to the predetermined criteria. Additionally, we performed an updated database search from July 2021 to October 2022. Finally, this study included nine publications.

Summary of studies

The included studies comprised seven retrospective cohort studies and two prospective cohort studies (Table 1). The study populations in the original research were from well-documented databases, including two from a cohort of 11,001 patients with IBD, one from an administrative claims database, two from the Nationwide Readmissions Database, two from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program database, one from a cohort of patients with CD or UC using electronic health records, and one from the Nationwide Patient Register database. Of the nine enrolled studies, seven both CD and UC in IBD types, one included only CD and one included only UC. The nine studies included a total of 1,495,695 participants, and 175,154 were identified as having frailty at the time of inclusion, with a frailty rate of 11.71%. Table 1 shows the overall traits of the included studies.

Study quality

The included publications were all cohort studies without randomized controlled studies. Quality evaluation was conducted using the NOS scale. The overall quality of the studies was good, with scores ranging between 7 and 9. Studies with NOS scores ≥ 8 were deemed to be high quality. After being included in the research participation score, seven articles were considered high quality, and two articles were rated with 7 points. The quality score was also good. Additional file 1: Table S1 shows the quality assessment.

Prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD

Among 1,495,695 study participants in the nine included studies, a total of 175,154 patients had frailty. We performed a meta-analysis of the frailty prevalence in the populations included in the nine studies, and the final pooled prevalence was 18% (95% CI: 12–24%, p = 0.000) (Fig. 2). Because I2 = 99.9% and p < 0.001, we choose the random-effects model to assess prevalence.

We performed a subgroup analysis of study design, male proportion, sample size, participants, frailty criteria, and follow-up (Additional file 1: Table S2). Meta-regression showed that the sex ratio was a possible source of heterogeneity (β = − 0.223, standard error = 0.068, p = 0.011) (Additional file 1: Table S3). In the subgroup by sex, the prevalence of male proportion ≥ 50% was 0.36 (95% CI: 0.29–0.43) and that of male proportion < 50% was 0.14 (95% CI: 0.07–0.20). Additionally, we performed subgroup analysis for age, but there were insufficient data to confirm that age was responsible for differences in the prevalence of frailty among patients with IBD (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Our funnel plot was symmetrical (Additional file 1: Fig. S1), and the Begg’s test (p = 0.371) and Egger’s test (p = 0.242) also indicated no publication bias. Additionally, sensitivity analysis showed no significant change in the pooled results after excluding individual studies one by one. This proved that the results were stable (Additional file 1: Fig. S2).

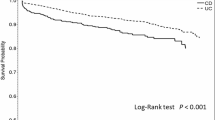

Primary outcome

In the nine included studies, we focused mainly on clinical outcomes associated with frailty factors in patients with IBD. The primary outcome is mortality in our study. We extracted the hazard ratio (HR) of mortality from the included studies and subsequently performed corresponding meta-analysis. Two studies [25, 36] reported mortality in frail IBD patients (n = 16,771) and in non-frail IBD patients (n = 41,221). Combined effect analysis showed that frailty increased the risk of mortality in patients with IBD compared with patients who had IBD without frailty (adjusted HR 2.25, 95% CI: 1.11–4. 55).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes included infection, hospitalization, readmission, and IBD-related surgery. In this study, we did not have sufficient data to confirm that frailty increases the risk of infection (adjusted HR 1.23, 95% CI 0.94–1.60) and hospitalization (adjusted HR 1.72, 95% CI: 0.88–3.36) in patients with IBD. One of the studies [25] reported that frail patients with IBD were more susceptible to readmission treatment (adjusted HR 1.21, 95% CI: 1.17–1.25), and frailty reduced the risk of IBD-related surgery (adjusted HR 0.78, 95% CI: 0.66–0.91) (Table 2).

Discussion

In our study, we found that frailty was common in patients with IBD. Compared with the general population, patients with IBD have a higher prevalence of frailty [36]. Our results also showed that frailty was associated with increased mortality risk in patients with IBD. However, frailty reduces the risk of IBD-related surgery perhaps because doctors do not recommend surgical treatment for frail patients with IBD. We included high-quality studies, adjusted the corresponding confounding factors, and conducted subgroup analysis and meta-regression analysis to deal with the heterogeneity among different studies such that our study findings were stable and reliable.

In the long-term process of the inflammatory bowel disease disease, there is a decline in the reserves of multiple physiological systems and a chronic increase in the level of circulating inflammatory markers. In a cross-sectional study of 117 participants aged 62–95 years, frailty was associated with increased serum interleukin 6, soluble tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-αreceptor-I as well as soluble TNF-αreceptor-II, suggesting an association of frailty with circulating markers of inflammation [37]. Another study showed that signs of frailty and circulatory inflammation are associated with the incidence of multiple complications and infections [38]. Immunosuppressive drugs are often used to treat IBD. Patients using such drugs have a weak immune response, which is one reason for frailty and an increased risk of infections [39]. Additionally, frailty patients have a reduced ability to recover, and an increased probability of complications [40], which may make the treatment of patients with IBD more difficult [41] and reduce the possibility of recovery to baseline, increasing the chance of hospitalization [42,43,44]. Frailty is a stress response owing to the imbalance of immune, endocrine, and energy response systems, Frailty is dynamic, but its specific biological basis has not been fully clarified. According to the existing evidence, frailty is related to increased systemic inflammatory markers [45,46,47]. Thus, there is reason to believe that the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD is higher than in those without IBD.

Frailty is an important measure of functional status [48]. It is considered a biological syndrome with reduced reserves caused by the cumulative decline of multiple physiological functions or a risk index based on the accumulation of health defects [2, 49]. Its relevant definitions include diagnoses related to dementia, visual impairment, bedsores, fecal incontinence, social support needs, action capability, and nutritional problems [50]. Although many well-validated methods for assessing frailty have been developed in the general adult and elderly populations, there are no fully validated tools for assessing frailty in the population of patients with IBD [51, 52]. The nine cohort studies included in this review used several different frailty assessment tools. Surprisingly, even with the same frailty assessment tool, the cut-off in frailty assessment differed among cohorts. This may be because there is no gold standard to assess frailty to date. Because of differences in the data sources of the original research, different studies used different assessment tools and diagnostic criteria for frailty, which may be one reason for the large heterogeneity in our included studies. This also suggests that more research is needed to improve diagnostic criteria as well as more systematic evaluation of frailty in patients with IBD.

Bedard et al. [54] published a systematic review that described the clinical outcomes of frailty in patients with IBD. Our study is the first systematic assessment and meta-analysis of frailty in patients with IBD in recent years. We described the relationship between frailty and various clinical outcomes of IBD diseases, including mortality, infection, readmission, hospitalization, and IBD-related surgery. This work further supports frailty as an important prognostic factor, independent of age and comorbidity. Frailty is a crucial risk stratification factor in patients with IBD to help identify particularly high-risk adverse events in this population and determine the best treatment for improving outcomes in frail patients with IBD. Our work also supports the value of clinical frailty screening in patients with IBD at admission to better treat the disease.

Our study adds to the existing literature on frail patients with IBD and has several advantages. An important strength is that we examined the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD and the relationship between frailty and clinical outcomes in these patients; this is more efficient and valuable than research of single effect estimates. We found a higher prevalence of frailty and greater risk of mortality in patients with IBD. This highlights the need for clinicians to pay greater attention to frailty in patients with IBD and to intervene early in these patients to prevent adverse outcomes, reduce health care expenditures, and increase the life expectancy of patients with IBD. Another advantage of this study is the inclusion of a large population of patients with IBD. We performed a pooled analysis of prevalence using a large sample size. This facilitates more accurate estimates of the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD. Our study is limited in that we did not perform subgroup analysis of clinical outcomes in the included cohort studies because of insufficient data on the impact of frailty on clinical outcomes in patients with IBD. Also, the small number of included publications may affect the credibility of the results. Further studies are warranted to confirm our results in the future.

Conclusions

In the present meta-analysis of nine cohort studies based on the population with IBD, we found that frailty is increasingly prevalent among patients with IBD and that frailty is a significant and independent predictor of mortality in these patients. Our work highlights the value of implementing frailty screening in patients with IBD on admission. Further research to identify gold standard criteria for diagnosing and evaluating frailty is needed, as well as prospective studies focused on the impact of frailty in patients with IBD, to improve the poor prognosis of frail patients with IBD.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Chen X, Mao G, Leng SX. Frailty syndrome: an overview. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:433–41.

Hoogendijk EO, Afilalo J, Ensrud KE, Kowal P, Onder G, Fried LP. Frailty: implications for clinical practice and public health. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1365–75.

Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(2):719–36.

Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of disabilities among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(19):1897–908.

Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146-156.

Hoogendijk EO, Suanet B, Dent E, Deeg DJ, Aartsen MJ. Adverse effects of frailty on social functioning in older adults: results from the longitudinal aging study Amsterdam. Maturitas. 2016;83:45–50.

Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of future falls among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1027–33.

Ensrud KE, Ewing SK, Taylor BC, Fink HA, Stone KL, Cauley JA, Tracy JK, Hochberg MC, Rodondi N, Cawthon PM. Frailty and risk of falls, fracture, and mortality in older women: the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(7):744–51.

Kojima G, Iliffe S, Jivraj S, Walters K. Association between frailty and quality of life among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(7):716–21.

Soysal P, Veronese N, Thompson T, Kahl KG, Fernandes BS, Prina AM, Solmi M, Schofield P, Koyanagi A, Tseng PT, et al. Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;36:78–87.

Kojima G, Taniguchi Y, Iliffe S, Walters K. Frailty as a predictor of alzheimer disease, vascular dementia, and all dementia among community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(10):881–8.

Robertson DA, Savva GM, Kenny RA. Frailty and cognitive impairment—a review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev. 2013;12(4):840–51.

Kojima G. Frailty as a predictor of nursing home placement among community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2018;41(1):42–8.

Handforth C, Clegg A, Young C, Simpkins S, Seymour MT, Selby PJ, Young J. The prevalence and outcomes of frailty in older cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol. 2015;26(6):1091–101.

Kojima G, Iliffe S, Walters K. Frailty index as a predictor of mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):193–200.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, King E, Orandi B, Salter M, Gupta N, Chow E, Alachkar N, Desai N, Varadhan R, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2015;15(1):149–54.

Abraham BP. Symptom management in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(7):953–67.

Alatab S, Sepanlou SG, Ikuta K, Vahedi H, Bisignano C, Safiri S, Sadeghi A, Nixon MR, Abdoli A, Abolhassani H, Alipour V. The global, regional, and national burden of inflammatory bowel disease in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(1):17–30.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Donaldson T, Lasch K, Yajnik V. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in the elderly patient: challenges and opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(6):882–93.

Jeuring SF, van den Heuvel TR, Zeegers MP, Hameeteman WH, Romberg-Camps MJ, Oostenbrug LE, Masclee AA, Jonkers DM, Pierik MJ. Epidemiology and long-term outcome of inflammatory bowel disease diagnosed at elderly age—an increasing distinct entity? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(6):1425–34.

Nguyen GC, Sheng L, Benchimol EI. Health care utilization in elderly onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(4):777–82.

Sturm A, Maaser C, Mendall M, Karagiannis D, Karatzas P, Ipenburg N, Sebastian S, Rizzello F, Limdi J, Katsanos K, et al. European crohn’s and colitis organisation topical review on IBD in the elderly. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(3):263–73.

Nguyen GC, Bernstein CN, Benchimol EI. Risk of surgery and mortality in elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(2):218–23.

Wolters FL, Russel MG, Sijbrandij J, Schouten LJ, Odes S, Riis L, Munkholm P, Bodini P, O’Morain C, Mouzas IA, et al. Crohn’s disease: increased mortality 10 years after diagnosis in a Europe-wide population based cohort. Gut. 2006;55(4):510–8.

Qian AS, Nguyen NH, Elia J, Ohno-Machado L, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Frailty is independently associated with mortality and readmission in hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2021;19(10):2054-2063.e2014.

Kochar BD, Cai W, Ananthakrishnan AN. Inflammatory bowel disease patients who respond to treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents demonstrate improvement in pre-treatment frailty. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67(2):622–8.

Kochar B, Cai W, Cagan A, Ananthakrishnan AN. Frailty is independently associated with mortality in 11 001 patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52(2):311–8.

Kochar B, Cai W, Cagan A, Ananthakrishnan AN. pretreatment frailty is independently associated with increased risk of infections after immunosuppression in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(8):2104-2111.e2102.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–58.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101.

Stuck AE, Rubenstein LZ, Wieland D: Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Asymmetry detected in funnel plot was probably due to true heterogeneity. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 1998, 316(7129):469; author reply 470–461.

Faye AS, Wen T, Soroush A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Ungaro R, Lawlor G, Attenello FJ, Mack WJ, Colombel JF, Lebwohl B. Increasing prevalence of frailty and its association with readmission and mortality among hospitalized patients with IBD. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(12):4178–90.

Singh S, Heien HC, Sangaralingham L, Shah ND, Lai JC, Sandborn WJ, Moore AA. Frailty and risk of serious infections in biologic-treated patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27(10):1626–33.

Wolf JH, Hassab T, D’Adamo CR, Svoboda S, Demos J, Ahuja V, Katlic M. Frailty is a stronger predictor than age for postoperative morbidity in Crohn’s disease. Surgery. 2021;170(4):1061–5.

Kochar B, Jylhävä J, Söderling J, Ritchie CS, Ludvigsson JF, Khalili H, Olén O. Prevalence and implications of frailty in older adults with incident inflammatory bowel diseases: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol Off Clin Pract J Am Gastroenterol Assoc. 2022;20(10):2358-2365.e2311.

Van Epps P, Oswald D, Higgins PA, Hornick TR, Aung H, Banks RE, Wilson BM, Burant C, Graventstein S, Canaday DH. Frailty has a stronger association with inflammation than age in older veterans. Immun Ageing. 2016;13:27.

Ferrucci L, Fabbri E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15(9):505–22.

Fülöp T, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Human T cell aging and the impact of persistent viral infections. Front Immunol. 2013;4:271.

Hope AA, Gong MN, Guerra C, Wunsch H. Frailty before critical illness and mortality for elderly medicare beneficiaries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(6):1121–8.

Rajabali N, Rolfson D, Bagshaw SM. Assessment and utility of frailty measures in critical illness, cardiology, and cardiac surgery. Can J Cardiol. 2016;32(9):1157–65.

Joseph B, Pandit V, Zangbar B, Kulvatunyou N, Hashmi A, Green DJ, O’Keeffe T, Tang A, Vercruysse G, Fain MJ, et al. Superiority of frailty over age in predicting outcomes among geriatric trauma patients: a prospective analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(8):766–72.

Robinson TN, Eiseman B, Wallace JI, Church SD, McFann KK, Pfister SM, Sharp TJ, Moss M. Redefining geriatric preoperative assessment using frailty, disability and co-morbidity. Ann Surg. 2009;250(3):449–55.

McDermid RC, Stelfox HT, Bagshaw SM. Frailty in the critically ill: a novel concept. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):301.

Hubbard RE, O’Mahony MS, Savva GM, Calver BL, Woodhouse KW. Inflammation and frailty measures in older people. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13(9b):3103–9.

Collerton J, Martin-Ruiz C, Davies K, Hilkens CM, Isaacs J, Kolenda C, Parker C, Dunn M, Catt M, Jagger C, et al. Frailty and the role of inflammation, immunosenescence and cellular ageing in the very old: cross-sectional findings from the Newcastle 85+ study. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133(6):456–66.

Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH Jr, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R. Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106(5):506–12.

Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 2013;381(9868):752–62.

Ferrucci L, Gonzalez-Freire M, Fabbri E, Simonsick E, Tanaka T, Moore Z, Salimi S, Sierra F, de Cabo R. Measuring biological aging in humans: a quest. Aging Cell. 2020;19(2):e13080.

Goel AN, Lee JT, Gurrola JG 2nd, Wang MB, Suh JD. The impact of frailty on perioperative outcomes and resource utilization in sinonasal cancer surgery. Laryngoscope. 2020;130(2):290–6.

de Vries NM, Staal JB, van Ravensberg CD, Hobbelen JS, Rikkert MGO, Sanden MWN-VD. Outcome instruments to measure frailty: a systematic review. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(1):104–14.

Morley JE, Vellas B, van Kan GA, Anker SD, Bauer JM, Bernabei R, Cesari M, Chumlea WC, Doehner W, Evans J, et al. Frailty consensus: a call to action. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(6):392–7.

Telemi E, Trofymenko O, Venkat R, Pandit V, Pandian TK, Nfonsam VN. Frailty predicts morbidity after colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Am Surg. 2018;84(2):225–9.

Bedard K, Rajabali N, Tandon P, Abraldes JG, Peerani F. Association between frailty or sarcopenia and adverse outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Gastro Hep Adv. 2022;1(2):241–50.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Jianghua Zhou and Pan Huang for their assistance throughout the development of our study.

Funding

There was no funding support for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Author notes

Xiangting Huang and Mengmeng Xiao: Mainly participate in all the work of this project

Contributions

XH and PZ contributed to the conception and design of the study. XH and XX drafted the manuscript, MX and XX analyzed and examined the data. YC and XX participated in the literature search, quality assessment, and writing work. JW, XW, SY, SW, XT, and BJ participated in literature screening and data extraction. SW participated in the Modification. All the authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed to publish.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

: Table S1: The quality of included studies by NOS scale (cohort study). Table S2: Subgroup analysis for prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD. Table S3: Meta-regression for the prevalence of frailty. Figure S1: Funnel plot of prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD. Figure S2: Sensitivity analysis of the prevalence of frailty in patients with IBD.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Xiao, M., Jiang, B. et al. Prevalence of frailty among patients with inflammatory bowel disease and its association with clinical outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol 22, 534 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02620-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-022-02620-3