Abstract

Background

The technique of percutaneous aortic valve implantation (PAVI) for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis (AS) has been introduced in 2002. Since then, many thousands such devices have worldwide been implanted in patients at high risk for conventional surgery. The procedure related mortality associated with PAVI as reported in published case series is substantial, although the intervention has never been formally compared with standard surgery. The objective of this study was to assess the safety of PAVI, and to compare it with published data reporting the risk associated with conventional aortic valve replacement in high-risk subjects.

Methods

Studies published in peer reviewed journals and presented at international meetings were searched in major medical databases. Further data were obtained from dedicated websites and through contacts with manufacturers. The following data were extracted: patient characteristics, success rate of valve insertion, operative risk status, early and late all-cause mortality.

Results

The first PAVI has been performed in 2002. Because of procedural complexity, the original transvenous approach from 2004 on has been replaced by the transarterial and transapical routes. Data originating from nearly 2700 non-transvenous PAVIs were identified. In order to reduce the impact of technical refinements and the procedural learning curve, procedure related safety data from series starting recruitment in April 2007 or later (n = 1975) were focused on. One-month mortality rates range from 6.4 to 7.4% in transfemoral (TF) and 11.6 to 18.6% in transapical (TA) series. Observational data from surgical series in patients with a comparable predicted operative risk, indicate mortality rates that are similar to those in TF PAVI but substantially lower than in TA PAVI. From all identified PAVI series, 6-month mortality rates, reflecting both procedural risk and mortality related to underlying co-morbidities, range from 10.0-25.0% in TF and 26.1-42.8% in TA series. It is not known what the survival of these patients would have been, had they been treated medically or by conventional surgery.

Conclusion

Safety issues and short-term survival represent a major drawback for the implementation of PAVI, especially for the TA approach. Results from an ongoing randomised controlled trial (RCT) should be awaited before further using this technique in routine clinical practice. In the meantime, both for safety concerns and for ethical reasons, patients should only be subjected to PAVI within the boundaries of such an RCT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

The first human percutaneous aortic valve implantation (PAVI) has been performed by Cribier in April 2002[1]. The initial antegrade transvenous technique through the interatrial septum later on was replaced by the retrograde transarterial approach. For patients in whom vascular access was rendered impossible due to severe atheromatous disease, the transapical route was designed, where PAVI occurs directly through the left ventricular apex, involving a mini-thoracotomy. So far, results from over 3500 PAVIs have been made public[2, 3]. Although both European[4] and American[5] professional organisations emphasise safety issues, many single or multiple case series continue to be reported. We recently performed a Health Technology Assessment on PAVI[6]. The safety issues emerging from this review are discussed here.

Methods

On December 15, 2008, both authors searched Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, and CRD databases, using relevant subject headings and a collection of text words representing the concept of PAVI. Furthermore, internet-based sources dedicated to dissemination of results from cardiovascular trials http://www.tctmd.com, http://www.medscape.com were searched. We also contacted interventional cardiologists and manufacturers. Full details of the search strategy have been described elsewhere[6] and are accessible from our website http://www.kce.fgov.be/index_en.aspx?SGREF=10504%26CREF=12227. To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to report experience with transarterial or transapical PAVI in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS). Transvenous PAVI was not considered. Single-case reports were excluded because of their obvious anecdotal nature. Only devices that have been granted European CE marking were taken into consideration: the Edwards Lifesciences device (or any of its predecessors) and the CoreValve Revalving System. The CE marking denotes a formal statement by the manufacturer of compliance with EU directives requirements. Unlike the pharmaceutical sector, where new drugs have to undergo series of regulatory clinical trials during development, the evaluation of medical devices is less demarcated and no pre-market clinical trials are required for obtaining CE marking[7].

The following data were extracted: operative risk score, valve type and approach, number of patients in the series, time frame of the series, implantation success rate, procedural (defined as 30-day) mortality, and longer term mortality if available.

Results

CRD and the Cochrane database revealed no systematic reviews on PAVI. No data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified. The National Institutes of Health clinical trials registry http://www.clinicaltrials.gov mentioned one RCT in progress. Our selection process resulted in 15 case series that further in this review are referred to as "published series". Extracted data are depicted in Table 1.

Unpublished data were obtained through contacts with manufacturers and from webposted 2008 conference proceedings: EuroPCR08, Transcatheter Valve Therapy, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery and Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics. These unpublished data are referred to as "presented series" further in this review. Thirteen case series (Table 2) with a dedicated acronym were identified; reference to these in the published series rarely occurred. Based on the names of participating authors and on the time window of patient recruitment, it seems that most of the cases that have been discussed in published papers are part of the presented series. Patient characteristics and outcome data from presented series are provided in Table 2. Data from 2692 patients were identified, 76% of which were treated via the transfemoral (TF) and 24% via the transapical (TA) route. Their mean age was about 82 years. In all series operative risk was estimated by means of the logistic EuroSCORE http://www.euroscore.org. Some series did also provide the risk by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk tool http://www.sts.org. The EuroSCORE of TF treated patients was lower than that of TA treated subjects. Data related to the same registry were not always identical from different sources. In Table 2, we entered the most recently presented data that we could identify. Technical success of PAVI was not always defined in the same way among different registries. For example, in a report of the PARTNER EU registry, Lefèvre reports a 96.3% success rate (52/54), although PAVI was reportedly aborted in 6 patients out of 60 planned because of vascular access problems, a failed balloon valvuloplasty or the detection of endocarditis[8] Incorporating these data would result in a success rate of 86.7% (52/60).

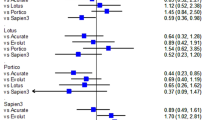

In order to reduce the impact of technical refinements and the procedural learning curve, a summary estimate of PAVI safety is calculated from series starting recruitment in April 2007 or later (n = 1975). In these registries, one-month mortality rates range from 6.4 to 7.4% in TF and 11.6 to 18.6% in TA series. From all identified PAVI series, six-month mortality ranges from 10-25.0% following TF and 26.1-42.8% following TA procedures.

Discussion

By introducing a percutaneous approach for aortic valve insertion, it was hypothesised that elderly and frail patients in whom this less-invasive procedure was performed would run a lower procedural risk than when treated by conventional aortic valve replacement (AVR)[9]. Since the first PAVI in 2002, many thousands such devices have been implanted worldwide. In the initial antegrade transseptal approach a procedure attributable mortality risk of 25% was noted,[10] which initiated the development of the less demanding retrograde TF technique. The latter can however be hampered due to difficulties to advance large catheters through tortuous and diffusely diseased femoral and iliac arteries, often encountered in elderly people. These restrictions have led to the development of the TA approach where the same device is introduced from the cardiac apex via a mini-thoracotomy. Due to this selection process, patients treated by the TA route mostly have a higher risk profile than those treated by the TF approach which is reflected in their higher EuroSCORE.

The available data demonstrate that even at experienced centers, PAVI remains a risky procedure. In series starting recruitment in April 2007 or later, i.e. after European market approval, one-month mortality rates range from 6.4 to 7.4% in TF and 11.6 to 18.6% in TA series. In these patients, it is uncertain what their survival would have been if they had been operated conventionally or treated medically. It also remains unclear to what extent a patient's overall quality of life is improved by the procedure, provided he or she survives the intervention. There are no sound criteria to assess the appropriateness to proceed to correction of a symptomatic AS (whether by surgery or PAVI) in frail elderly patients with substantial co-morbidities. Depending on the pre-procedural clinical condition that remains unaffected by correcting the AS, the quality of life may hardly be altered by a successful PAVI. In this respect, recent guidelines state that "valve replacement is technically possible at any age, but the decision to proceed with such surgery depends on many factors ... Deconditioned and debilitated patients often do not return to an active existence, and the presence of the other comorbid disorders could have a major impact on outcome[11]."

In a literature review on AVR in the octogenarian, operative mortality of isolated AVR varied between 4.3 and 10.3%[12]. Very recently operative results of 1000 "minimally invasive" (i.e. parasternal approach or hemisternotomy) AVRs were reported. Among 160 patients of 80 years or older undergoing isolated AVR, operative mortality rate was 1.9%[13]. Svensson et al. report the fate of 163 patients that were referred to their institutions for potential PAVI because of putative inoperability[14]. Twenty nine of them were treated by conventional AVR with no operative deaths. High-surgical-risk and operability status are poorly defined concepts and complicate the interpretation of outcomes from observational data. The operative risk of patients contemplated for PAVI have mostly been estimated through the EuroSCORE but its performance in high-risk patients has been critisised [15–19]. Recent observational data from surgically treated patients indicate that the EuroSCORE severely overestimates postoperative mortality in high-risk patients undergoing an isolated AVR. In a surgical series from the Mayo Clinic, a predicted 30-day mortality of 23.6% sharply contrasted with an observed mortality of only 5.8%[20]. By comparing this figure with 30-day mortality rates observed in PAVI (Table 2), it could be argued that patients with AS that are considered at high risk for conventional surgery, may actually run a higher mortality risk if treated by means of PAVI than when treated surgically. Only data from an RCT would enable to clarify this.

Six-month mortality of patients treated by PAVI, reflecting both procedural risk and mortality from underlying co-morbidities, is also very high and ranges from 10-25.0% in TF series and 26.1-42.8% in TA series (Tables 1 and 2). The wide range in the observed short term mortality rate may result from the chosen interventional approach for PAVI and from differences in patient selection. The EuroSCORE does not take into account several conditions that are often encountered in elderly patients, yet are determinants for both life expectancy and quality of life, even following successful PAVI: coronary artery disease, heart failure, diabetes, presence and degree of mitral regurgitation, arrhythmias, previous stroke, renal failure on dialysis[21, 22]. This might explain that in a series of 50 patients reported by Webb, 6-month survival of 7 patients in whom PAVI failed (86%) was similar to 6-month survival of 43 successfully treated cases (81%)[23].

One-year survival after PAVI ranges from 65-80% in TF series and from 54.7-66% in TA series. In an observational study encompassing 277 elderly patients (> 80 years) 80 underwent surgical AVR and 197 were treated medically. One-year survival among patients with AVR was 87%, compared with 52% in those who had no AVR[24]. Data from the European Heart Survey showed a 1-year survival among 72 patients (> 75 years old) with severe symptomatic AS in whom it was decided not to operate, of 84.8 ± 4.8%[25]. In a US series of 75 unoperated patients aged 68.1 ± 15.0 years, with severe symptomatic AS, one-year survival was 62%[26]. The poor one-year survival of patients following PAVI overlaps with that of patients treated conservatively. This can at least partly be explained by a high procedural mortality rate and the very poor general condition with inherent competing mortality risk of the patients involved, questioning the appropriateness of an intervention directed towards a correction of the AS in this population.

The major shortcoming of published series and cases presented at international meetings, the data of which are summarised here, is the lack of randomisation of eligible patients to an intervention group treated with PAVI, versus a control group. Moreover, data published in peer reviewed journals reflect the experience of specified authors, whereas the data from compiled PAVI series presented at meetings are entirely under control of the manufacturers involved. Participation in some of the registries and the reporting of outcomes in some instances is on a voluntary basis only. We were unable to verify the completeness and the correctness of reported mortality rates. One-year mortality rates that are referred to in this paper obviously stem from earlier series, and may not be applicable to more recent experience. Therefore, the results of our study and from any non-randomised trial should be interpreted with caution.

Although data from an increasing number of patients are published in journals and presented at meetings, they do not add to our understanding of the potential of this new technology. The methodological shortcomings prevailing in all these series remain unaltered, i.e. the data are merely observational from selected and unrandomised patient groups.

Conclusion

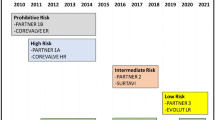

The safety issues pointed out above reinforce the contention that an RCT is badly needed to clarify the safety and the performance of PAVI in frail and elderly patients. In the years to come, evidence will be provided by an ongoing RCT, the PARTNER-IDE (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00530894)[3]. One might wonder whether in the meantime subjecting patients to PAVI can be justified.

References

Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, Borenstein N, Tron C, Bauer F, Derumeaux G, Anselme F, Laborde F, Leon MB: Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case description. Circulation. 2002, 106: 3006-3008. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000047200.36165.B8.

CoreValve ReValving Clinical Experience Post CE Mark Expanded Evaluation Registry. (accessible after free registration at tct.com), [http://www.tctmd.com/Show.aspx?id=73400]

The Edwards-Sapien Transcatheter AVR System: Patient Selection, Device and Procedural Evolution, Implant Success and Complications, and Long-Term Durability. (accessible after free registration at tct.com), [http://www.tctmd.com/txshow.aspx?tid=2458%26id=70880%26trid=2380]

Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, Butchart E, Dion R, Filippatos G, Flachskampf F, Hall R, Iung B, Kasprzak J, Nataf P, Tornos P, Torracca L, Wenink A, Task Force on the Management of Valvular Hearth Disease of the European Society of C, Guidelines ESCCfP: Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: The Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. European heart journal. 2007, 28: 230-268.

Rosengart TK, Feldman T, Borger MA, Vassiliades TA, Gillinov AM, Hoercher KJ, Vahanian A, Bonow RO, O'Neill W: Percutaneous and minimally invasive valve procedures: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group, and Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008, 117: 1750-1767. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.188525.

Van Brabandt H, Neyt M: Percutaneous heart valve implantation in congenital and degenerative valve disease. A rapid Health Technology Assessment. 2008, Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), Brussels, Belgium

Vinck I, Neyt M, Thiry N, Louagie M, Ghinet D, Cleemput I, Ramaekers D: A framework for the assessment of emerging medical devices. 2006, Belgium Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), Brussels, Belgium

Have the Outcomes Changed after CE Approval? Update from the PARTNER EU and SOURCE Registries. (accessible after free registration at tct.com), [http://www.tctmd.com/txshow.aspx?tid=2550%26id=73392%26trid=2380]

Vahanian A, Alfieri O, Al-Attar N, Antunes M, Bax J, Cormier B, Cribier A, De Jaegere P, Fournial G, Kappetein AP, Kovac J, Ludgate S, Maisano F, Moat N, Mohr F, Nataf P, Pierard L, Pomar JL, Schofer J, Tornos P, Tuzcu M, van Hout B, Von Segesser LK, Walther T, European Association of Cardio-Thoracic S, European Society of C, European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular I: Transcatheter valve implantation for patients with aortic stenosis: a position statement from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). European heart journal. 2008, 29: 1463-1470. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn183.

Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, Bauer F, Agatiello C, Nercolini D, Tapiero S, Litzler PY, Bessou JP, Babaliaros V: Treatment of calcific aortic stenosis with the percutaneous heart valve: mid-term follow-up from the initial feasibility studies: the French experience. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2006, 47: 1214-1223. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.049.

American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G, Society of Cardiovascular A, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and I, Society of Thoracic S, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, de Leon AC, Faxon DP, Freed MD, Gaasch WH, Lytle BW, Nishimura RA, O'Gara PT, O'Rourke RA, Otto CM, Shah PM, Shanewise JS, Smith SC, Jacobs AK, Adams CD, Anderson JL, Antman EM, Faxon DP, Fuster V, Halperin JL, Hiratzka LF, Hunt SA, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Page RL, Riegel B: ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): developed in collaboration with the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2006, 114: e84-231. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857.

Iung B: Management of the elderly patient with aortic stenosis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2008, 94: 519-524.

Tabata M, Umakanthan R, Cohn LH, Bolman RM, Shekar PS, Chen FY, Couper GS, Aranki SF: Early and late outcomes of 1000 minimally invasive aortic valve operations. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2008, 33: 537-541.

Svensson LG, Dewey T, Kapadia S, Roselli EE, Stewart A, Williams M, Anderson WN, Brown D, Leon M, Lytle B, Moses J, Mack M, Tuzcu M, Smith C: United States feasibility study of transcatheter insertion of a stented aortic valve by the left ventricular apex. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2008, 86: 46-54. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.049. discussion 54-45.

Bridgewater B, Keogh B: Surgical "league tables": ischaemic heart disease. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2008, 94: 936-942.

Dewey TM, Brown D, Ryan WH, Herbert MA, Prince SL, Mack MJ: Reliability of risk algorithms in predicting early and late operative outcomes in high-risk patients undergoing aortic valve replacement. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008, 135: 180-187. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.011.

Antunes MJ: Percutaneous aortic valve implantation. The demise of classical aortic valve replacement?. European heart journal. 2008, 29: 1339-1341. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn180.

Grover FL, Mayer JE, Kouchoukos N, Guyton R, Edwards F, Bavaria J: Letter by Grover et al regarding article, "Percutaneous implantation of the CoreValve self-expanding valve prosthesis in high-risk patients with aortic valve disease: the Siegburg First-in-Man study". Circulation. 2007, 115: e612-10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675645. author reply e613.

Collart F, Feier H, Kerbaul F, Mouly-Bandini A, Riberi A, Mesana TG, Metras D: Valvular surgery in octogenarians: operative risks factors, evaluation of Euroscore and long term results. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2005, 27: 276-280.

Brown ML, Schaff HV, Sarano ME, Li Z, Sundt TM, Dearani JA, Mullany CJ, Orszulak TA: Is the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation model valid for estimating the operative risk of patients considered for percutaneous aortic valve replacement?. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008, 136: 566-571. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.091.

Walther T, Simon P, Dewey T, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Falk V, Kasimir MT, Doss M, Borger MA, Schuler G, Glogar D, Fehske W, Wolner E, Mohr FW, Mack M: Transapical minimally invasive aortic valve implantation: multicenter experience. Circulation. 2007, 116: I240-245. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.677237.

Roques F, Michel P, Goldstone AR, Nashef SAM: The logistic EuroSCORE. European heart journal. 2003, 24: 881-882. 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00799-6.

Webb JG, Pasupati S, Humphries K, Thompson C, Altwegg L, Moss R, Sinhal A, Carere RG, Munt B, Ricci D, Ye J, Cheung A, Lichtenstein SV: Percutaneous transarterial aortic valve replacement in selected high-risk patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2007, 116: 755-763. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.698258.

Varadarajan P, Kapoor N, Bansal RC, Pai RG: Survival in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis is dramatically improved by aortic valve replacement: Results from a cohort of 277 patients aged > or = 80 years. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2006, 30: 722-727.

Iung B, Cachier A, Baron G, Messika-Zeitoun D, Delahaye F, Tornos P, Gohlke-Barwolf C, Boersma E, Ravaud P, Vahanian A: Decision-making in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis: why are so many denied surgery?. European heart journal. 2005, 26: 2714-2720. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi471.

Bach DS, Cimino N, Deeb GM: Unoperated patients with severe aortic stenosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007, 50: 2018-2019. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.011.

Webb JG, Chandavimol M, Thompson CR, Ricci DR, Carere RG, Munt BI, Buller CE, Pasupati S, Lichtenstein S: Percutaneous aortic valve implantation retrograde from the femoral artery. Circulation. 2006, 113: 842-850. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.582882.

Grube E, Laborde JC, Gerckens U, Felderhoff T, Sauren B, Buellesfeld L, Mueller R, Menichelli M, Schmidt T, Zickmann B, Iversen S, Stone GW: Percutaneous implantation of the CoreValve self-expanding valve prosthesis in high-risk patients with aortic valve disease: the Siegburg first-in-man study. Circulation. 2006, 114: 1616-1624. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.639450.

Berry C, Asgar A, Lamarche Y, Marcheix B, Couture P, Basmadjian A, Ducharme A, Laborde JC, Cartier R, Bonan R: Novel therapeutic aspects of percutaneous aortic valve replacement with the 21F CoreValve Revalving System. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions: official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2007, 70: 610-616.

Grube E, Schuler G, Buellesfeld L, Gerckens U, Linke A, Wenaweser P, Sauren B, Mohr FW, Walther T, Zickmann B, Iversen S, Felderhoff T, Cartier R, Bonan R: Percutaneous aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis in high-risk patients using the second- and current third-generation self-expanding CoreValve prosthesis: device success and 30-day clinical outcome. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007, 50: 69-76. 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.047.

Lichtenstein SV, Cheung A, Ye J, Thompson CR, Carere RG, Pasupati S, Webb JG: Transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation in humans: initial clinical experience. Circulation. 2006, 114: 591-596. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632927.

Ye J, Cheung A, Lichtenstein SV, Pasupati S, Carere RG, Thompson CR, Sinhal A, Webb JG: Six-month outcome of transapical transcatheter aortic valve implantation in the initial seven patients. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2007, 31: 16-21.

Marcheix B, Lamarche Y, Berry C, Asgar A, Laborde JC, Basmadjian A, Ducharme A, Denault A, Bonan R, Cartier R: Surgical aspects of endovascular retrograde implantation of the aortic CoreValve bioprosthesis in high-risk older patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2007, 134: 1150-1156. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.031.

Walther T, Falk V, Borger MA, Dewey T, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Schuler G, Mack M, Mohr FW: Minimally invasive transapical beating heart aortic valve implantation--proof of concept. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2007, 31: 9-15.

Walther T, Falk V, Kempfert J, Borger MA, Fassl J, Chu MWA, Schuler G, Mohr FW: Transapical minimally invasive aortic valve implantation; the initial 50 patients. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2008, 33: 983-988.

Zierer A, Wimmer-Greinecker G, Martens S, Moritz A, Doss M: The transapical approach for aortic valve implantation. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2008, 136: 948-953. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.06.028.

Descoutures F, Himbert D, Lepage L, Iung B, Detaint D, Tchetche D, Brochet E, Castier Y, Depoix J-P, Nataf P, Vahanian A: Contemporary surgical or percutaneous management of severe aortic stenosis in the elderly. European heart journal. 2008, 29: 1410-1417. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn081.

Rodes-Cabau J, Dumont E, De LaRochelliere R, Doyle D, Lemieux J, Bergeron S, Clavel M-A, Villeneuve J, Raby K, Bertrand OF, Pibarot P: Feasibility and initial results of percutaneous aortic valve implantation including selection of the transfemoral or transapical approach in patients with severe aortic stenosis. The American journal of cardiology. 2008, 102: 1240-1246. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.061.

Largest Single-Center Experience with the Edwards-Sapien Balloon-Expandable Transcatheter Aortic Valve. (accessible after free registration at tct.com), [http://www.tctmd.com/txshow.aspx?tid=2550%26id=73384%26trid=2380]

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a state-of-the-art. (accessible after free registration at europcronline.com), [http://www.europcronline.com/fo/lecture/view_slide.php?idCongres=4%26id=4738]

TranscatheterTranscatheterAortic Valve Aortic Replacement: Clinical Indications, Technology Update, Clinical Trial Outcomes, and Future Directions. (accessible after free registration at tct.com), [http://www.tctmd.com/show.aspx?id=68490]

Transapical Valve Data: Climbing Survival Rates Speak to Improved Skill, Technology, and Patient Selection. (accessible after free registration at medscape.com), [http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/581520]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/9/45/prepub

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

Both authors are employees of KCE http://www.kce.fgov.be, an independent semi-governmental Health Technology Assessment agency and member of INAHTA http://www.inahta.org. We have no ties with industry or any other commercial organisation. We have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' contributions

Both authors contributed equally to this work.

Hans Van Brabandt and Mattias Neyt contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Brabandt, H., Neyt, M. Safety of percutaneous aortic valve insertion. A systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 9, 45 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-9-45

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-9-45