Abstract

Research suggests that single-issue groups and labor unions have been incorporated into one of the two US party coalitions (Karol in American gridlock: the sources, character, and impact of political polarization, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 68–85, 2015; Lacombe in J Polit, 10.1086/704329, 2019). But political scientists have not examined whether other types of groups, including trade and professional associations, have experienced such incorporation. I argue that some groups are closely aligned with one of the political parties, but others choose not to affiliate for strategic reasons rooted in their membership and policy goals. I develop a new measure—Party Proximity Index—to plot a unique dataset of 2040 interest groups on a partisan scale that provides valuable information about variation in interest group lobbying strategies, the ways interest groups mobilize their members, and groups’ relationships to parties over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Political science research suggests that single-issue groups and labor unions have chosen to affiliate with one of the two major US political parties (Karol 2015; Lacombe 2021). We see evidence of this phenomenon in groups’ contribution patterns, changes in electoral endorsement practices, and communication by groups like the National Rifle Association (Grossmann and Dominguez 2009; Bonica 2014; Karol 2019; Lacombe 2021). While this phenomenon among single-issue and labor groups is well-documented, political scientists have not fully explored whether other types of groups have been incorporated into the party system. In fact, some research suggests that some groups stay nonpartisan for strategic reasons (Walker 1991; Bonica 2013).

In a polarized political climate, why would interest groups avoid aligning with a political party? I argue some groups intentionally refrain from affiliating with one of the party coalitions for strategic reasons. The driver behind the decision to maintain nonpartisan status or affiliate with a political party has its core in organizational goals and interest group leaders’ determinations about the best way to achieve those goals. These organizational goals—particularly goals centered around member retention—drive interest groups’ public policy strategy, which leads groups to make different decisions about how closely to associate with political parties.

While the idea of interest group incorporation into political party coalitions has been explored in political science literature, there is currently no measure that allows scholars to determine the extent to which interest groups have been incorporated into one of the party coalitions. This project provides a novel measure that can be used to identify the extent to which a range of interest groups align themselves with a party. I develop a continuous measure of interest groups’ proximity to the political parties called Party Proximity Index (PPI). I use data on contributions from 2,040 interest groups to partisan committees from 2015 to 2020 obtained from the Federal Election Commission (FEC).

This measure uncovers important variation in how interest groups position themselves with respect to parties and reflects the fact that PAC contributions serve as a signal to elected officials and interest group members about interest group partisan preferences. I find varying degrees of party proximity, with some groups located at the inner core of a party coalition, others closer to one party but maintaining distance from the core party coalition, still others that are distant from both parties with slight preferences toward one or the other party, and a significant number that maintain complete neutrality.

PPI scores show that groups’ relationships to parties vary in systematic and significant ways. Confirming previous studies, labor unions and issue advocacy nonprofits tend to fall closer to the party coalitions. Professional associations tend to be located farther from the party coalitions, while trade associations and firms vary, with some falling closer to neutral and others leaning toward the Republican party. Additionally, PPI scores confirm that groups that produce scorecards or endorse candidates are not reflective of all interest groups, but rather are more likely to be partisan compared to groups that do not issue scorecards or endorse. I also compare PPI scores with Crosson et al.’s (2020) IGScores and find that the two scores measure related but distinct concepts. PPI uncovers the reality of how interest groups associate with political parties in today’s polarized climate, which is more varied than conventional wisdom dictates.

For scholars exploring interest group incorporation into political parties, PPI is an important development that more directly captures the relationship between groups and parties. By using partisan contribution patterns of interest groups, this measure of party affiliation contrasts with existing measures, which rely upon ideology as a proxy for political party (Bonica 2013; Crosson et al. 2020). It is important to note that, given that not all interest groups make political contributions, PPI does not assign a party proximity to all interest groups. Some scholars estimate that a minority of interest groups operate PACs (LaPira and Thomas 2017). However, when compared with the Crosson et al. measure, the PPI dataset contains scores for 1403 (67.77%) interest groups that are not present in Crosson et al.’s dataset. As a result, PPI provides an opportunity to evaluate a greater share of the interest groups landscape.

PPI provides new evidence of a nuanced relationship between interest groups and parties and has implications for future work, including understanding the role these groups play in polarizing or depolarizing their members. Contrary to conventional wisdom, there are a significant number of interest groups that are unaffiliated with either political party. PPI will also allow scholars to study, at a large scale, how interest group proximity to party shifts over time rather than relying on single cases.

Interest group incorporation into the party system

Walker (1991) theorized that as the interest group system grows, it becomes more polarized. Walker identified a tendency for groups to incorporate into political parties when he wrote, ‘Interest groups, as they struggle to advance their own problems, are steadily being drawn into the orbit of one of the two major parties, thus experiencing the consequences of electoral political and conflict within communities’ (Walker 1991, p. 146). Walker noted, however, that some groups engage in activities that are inherently nonpartisan. Some operate in niche fields that are not affected by partisan changes in government. Others can do business no matter which party holds power. However, even in 1991, Walker observed that the presence of these groups was declining.

Party scholars have also investigated the relationships between interest groups and political parties. Modern scholarship suggests that parties are made up not only of candidates, but also of ‘intense policy demanders’ like interest groups and party activists (Cohen et al. 2008; Bawn et al. 2012). Karol (2009) finds that labor unions and single-issue groups have been incorporated into party coalitions. He also suggests that although some groups have fully incorporated into one of the two parties, groups vary in the degree to which they have been incorporated into party coalitions (Karol 2009). For example, environmental groups and abortion-related groups are more closely tied to parties than groups representing farmers or veterans (Karol 2009, 2017, 2019). Krimmel (2017) finds that political leaders during the mid-twentieth Century worked to incorporate religious groups into the Republican coalition. In this work, she suggests that the US political system has been moving toward party/interest group alignment since this time (Krimmel 2017).

Existing work also suggests variation in the degree of proximity between groups and the parties. Victor and Reinhardt (2018) find that party coalitions are dynamic and can change over time, which means that any measure that charts interest group incorporation into political parties should take these shifting allegiances into account. To date, we do not have the ability to measure party proximity or how party proximity might vary over time.

Measuring interest group incorporation

While Karol and others open a door for measuring incorporation of interest groups into party coalitions, large-scale efforts to measure interest groups have thus far focused on ideology. Scholars have used a variety of approaches to measure the ideological focus of interest groups, including congressional scorecards, candidate endorsements, lobbying data, and political contributions.

One method for measuring ideology involves analyzing data from interest group endorsements and scorecards. McKay (2010) develops a measure of interest group ideology based on the ideological content of bills included in interest group scorecards and finds that centrist groups avoid using scorecards due to interest group member retention concerns (McKay 2010).

A second potential source of data involves using issue positions to impute ideology. Crosson et al. (2020) create a measure of interest group ideology by identifying ideal points based on group positions on congressional bills with roll-call votes. Crosson and his colleagues find that groups making political contributions are more likely to take moderate or centrist positions on issues, and groups that focus on public position taking are more polarized than groups that lobby or make political contributions (Crosson et al. 2020).

While federal lobbying data may seem like a possible source for a measure of ideology, a drawback of using lobbying data to derive ideology is that interest groups are required to disclose topics covered during congressional meetings—not the group’s issue positions—in federal lobbying disclosure reports. Scholars have addressed this shortcoming by inferring ideology from state-level lobbying disclosure data in three states that require issue position on disclosure reports (Thieme 2020). While this information is helpful for analyzing the behavior of state-level interest groups, the findings do not necessarily translate to the federal level.

Interest group political contributions offer another method for measuring interest group ideology. This method is particularly useful since we can distinguish access-oriented interest groups from ideological groups by looking at political contribution patterns. While earlier scholars believed that political contributions represented a quid pro quo, with legislators taking specific actions in exchange for political contributions, later scholars proposed an access-based contribution strategy for interest groups (Snyder 1992; Wright 2002). Using political contributions from labor unions, business associations, and trade associations, Snyder finds these groups contribute to incumbents more than challengers (Snyder 1992). Fouirnaies and Hall (2014) clarify by suggesting that while some groups use access-based strategies, others focus on promoting a certain cause or ideology. Access-oriented groups are more likely to support incumbents, while ideological-oriented groups are more likely to support challengers (Fouirnaies and Hall 2014).

Scholars have also used campaign finance data to understand the relationships between groups and parties. McCarty and Poole (1998) use campaign finance data to develop their PAC-NOMINATE score, which helps to explain how legislators choose between positions favored by interest groups and those favored by voters. Baker (2018), in her study of the efficacy of Federal PACs, uses contributions to the national party committees as a proxy for a group’s party proximity (Baker 2018). Barber and Eatough (2020) use political contribution data to investigate the extent to which different industries or issue areas have been politicized, which can drive different donation patterns by PACs. Groups representing issue areas that have not been politicized tend to be access-oriented givers, while groups representing issue areas that are polarized tend to be ideological givers.

Bonica (2013) uses state and federal contribution data to develop a CFScore, which identifies ideological ideal points for political candidates and contributors. Since the unit of analysis in Bonica’s work is the contributing political committee, not the interest group, this measure provides information about the ideology of candidates, PACs, and individual donors. For instance, Bonica (2013) finds that corporate and membership PACs are located in the center of a left–right distribution and that business-related PACs give strategically instead of ideologically when contributing to campaigns. However, since interest groups often have multiple committees at the state and federal level, CFScore data cannot be used to impute information about interest groups.

Despite this rich literature on capturing interest group ideology, there has not been similar attention paid to understanding groups’ links to parties, which are similar to but distinct from ideology (Ellis and Stimson 2012). While ideology and partisanship are related, there are some important theoretical differences that merit a separate measure for interest group party proximity. Importantly, parties, not ideology, hold power in Congress and dictate legislative agendas (Cox and Mccubbins 1993). As interest groups seek to influence policymaking in Congress, it is important to understand the relationships between parties and interest groups apart from ideology. These differences can sometimes lead to misclassification if relying on ideology as a measure for partisanship. For example, the group Republican Majority for Choice (RMC), a nonconnected PAC that supports pro-choice Republican candidates, gives exclusively to Republicans (Center for Responsive Politics 2022). This giving pattern would place RMC among groups that have been fully incorporated into the Republican party on a party proximity scale. However, since the recipients of RMC contributions are more ideologically moderate than the median Republican member of Congress, the group would fall close to the center of an ideological scale. Both measures might be accurate, but they lead to different conclusions since they are measuring two distinct concepts.

This research addresses the need to understand interest group party proximity by developing a continuous variable that allows scholars to measure an interest group’s distance from the political parties. A group’s proximity to one of the political parties can provide valuable insights about a group’s strategic objectives, membership mobilization strategies, and the way it goes about achieving its policy goals.

A theory of interest group party proximity

To develop the theory of party proximity, I build on existing literature and draw from my years of experience working with interest groups. I expect that there will be a significant number of interest groups choosing not to affiliate with a party. The driver behind the decision to maintain nonpartisan status or affiliate with a political party is centered around the group’s organizational goals and group leaders’ determinations about the best way to achieve those goals. These organizational goals, especially those related to member maintenance, drive an interest group’s public policy strategy, which leads groups to choose their proximity to the political parties. If a group fails to deliver on these incentives, the group risks dissolving (Salisbury 1992). Since different types of organizations have different goals, we see varying patterns of affiliation based on interest groups’ organization types.

Professional associations are primarily interested in member maintenance, meaning that associations need to continually provide value to members to keep individuals happy and paying their association dues. This dynamic leads professional associations to focus on the reasons members join, and also leads associations to avoid alienating members for fear of losing them. Members of professional associations tend to join to earn material benefits, which can include journal access, professional credentials, insurance discounts, and other incentives (Clark and Wilson 1961; Olson 1965). These motivations lead members to value legislative priorities that forward individual members’ professional goals, many of which do not fall cleanly into one party’s platform. In addition, professional associations tend to have memberships that cut across party lines (Adamy and Overberg 2019). Favoring one party or the other can run the risk of alienating members, which provides a motivation for associations to maintain political neutrality. Since professional associations are composed of individual memberships, they are particularly vulnerable to losing members after alienating them.

These member and policy goals play out in a variety of ways for professional associations, most of which lead the organization to avoid affiliation with either political party. For example, the American Medical Association (AMA) has several priority issues championed by members of both parties. The No Surprises Act, a bill restricting surprise hospital billing, was included in the 2021 Omnibus Appropriations Act and was sponsored by the leading Republican and Democrat on the House Energy and Commerce Committee—Reps. Frank Pallone (D-NJ) and Dave Walden (R-OR). The AMA also advocates for updating the Medicare payment schedule. The bipartisan effort is led by Reps. Ami Berra (D-CA) and Larry Bucshon (R-IN)—both physicians in Congress (Robezneiks 2021). Securing support from both sides of the aisle for these initiatives ensures that the issues, which are often left unresolved during a session of Congress, have a chance at passage when Congress switches hands. Since the AMA’s public policy goals tend to be centered around nonpartisan issues, securing bipartisan cosponsors is an achievable task.

Like professional associations, trade associations also prioritize member maintenance. Trade associations tend to have diverse issue portfolios, which do not fall cleanly into one-party coalition or the other. For example, the National Corn Growers Association’s (NCGA) top issues include the Farm Bill, a wide-ranging bill that is reauthorized every five years, and the ethanol mandate, which receives periodic consideration from Congress and has regulations set by the Environmental Protection Agency each year. These issues tend to get support and opposition from both sides of the aisle. While corn growers tend to be white, rural Republicans, the NCGA maintains relationships with legislators on both sides of the aisle because this strategy helps the organization accomplish its legislative goals. There is no way to predict which party will control Congress when the Farm Bill is considered in Congress. As a result, the NCGA is incentivized to have relationships with both Democrats and Republicans, since both parties have an equal chance at being in control when the bill receives consideration. In addition, provisions within the vast bill are supported by the Democratic and Republican parties at different rates, requiring the NCGA to lobby both sides of the aisle to secure support for these provisions. Additionally, the membership of NCGA consists of businesses instead of individual members, which means the organization is more free to pursue access-oriented strategies due to a more stable membership base. Since most trade associations have situations similar to that of NCGA, I expect that trade associations will be likely to maintain political neutrality.

While members of trade and professional associations can become involved in public policy goals as a means to accomplish other objectives, members of issue advocacy nonprofits tend to join these organizations for the express purpose of policy advocacy—what Clark and Wilson (1961) call purposive goals. Scholars find that party coalition building efforts have led these types of groups to incorporate with one of the political parties (Karol 2009). These groups tend to have membership from one party or the other and lobby on issues that are supported by one party and opposed by the other. Consequently, issue advocacy nonprofits tend to side with the party that has absorbed their issue into its party coalition, with organizations focused on gun rights and restricting abortion access incorporating into the Republican party and gun safety, pro-choice, and environmental organizations working with the Democratic party. There are other issue advocacy nonprofits—disease groups, for example—that lobby on mostly nonpartisan issues. I expect that those groups will not affiliate with either political party.

Labor unions also have member maintenance goals. Labor unions maintain their membership by advocating for better working conditions for their members. The most common tool for accomplishing this goal is collective bargaining—a tactic that Democrats support and Republicans oppose. As a result, the only choice labor unions have is to affiliate with the Democratic party.

Firms have a different set of goals compared to other interest groups—to maximize profits. In the recent past, this motivation has led most firms to have a natural ally in the Republican party, which tends to support tax cuts and fewer regulations. However, corporate lobbyists tend to use access-oriented strategies to maintain relationships with members on both sides of the aisle (Wright 2002; Fouirnaies and Hall 2014). This approach helps corporations achieve their policy goals when Democrats control one or both chambers of Congress, and helps corporations build relationships with members of Congress who have corporate presence in their districts regardless of the member of Congress’s party affiliation. Recently, many companies have started to reassess profit-making strategies, focusing on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) priorities and more actively advocating for social issues (Business RoundTable 2019). As a result, many large corporations have found themselves in opposition to the Republican party on key issues. For now, however, most corporations pursue a nonpartisan public policy strategy that values access over ideology.

Interest groups are varied, and not all groups have the same organizational policy goals. But for all groups, the allocation of their financial contributions reflects their policy goals. Thus, not all groups have the same contribution strategies. I expect groups that choose not to affiliate with political parties will attempt to give equally to candidates on both sides of the aisle, compared to the percentage the party occupies in Congress. This strategy enables groups to build relationships with legislators from both parties, which accomplishes their goal of maintaining membership and achieving legislative goals regardless of party control in government. The strategy also allows groups to prioritize giving to whoever holds the majority in Congress, providing more resources for committee chairs, subcommittee chairs, and others responsible for determining legislative agendas.

Groups that have been incorporated into one of the party coalitions use a different strategy in accomplishing their policy goals. Karol (2019, p. 68) suggests that ‘party-aligned interest groups work within parties to advance their policy goals via candidate selection and lobbying elected officials.’ Consequently, when an aligned group’s party holds the White House or the majority in Congress, the group is able to accomplish its legislative goals. When their party is out of power, the group concentrates on fundraising and organizing so that the party can gain power during the next election. This strategy leads party-aligned groups to contribute almost exclusively to one side of the aisle, since those contributions will support the group’s goal of being part of the majority coalition in government.

The challenge of measuring an interest group’s party affiliation

When measuring interest group party affiliation, it is important to identify a method that will isolate partisanship for a large number of groups. Endorsement data, scorecards, and lobbying data all have their drawbacks. Endorsements and scorecards provide an incomplete look at the interest group universe, since many groups, particularly trade and professional associations, shy away from making such definitive statements in support or opposition to candidates. This trend is particularly pronounced in the past 20 years. Data gathered from Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA) filings do not provide issue positions, making it difficult to connect a lobbying visit and the group’s bill position. Using state-level data that provides support of legislation is a promising option, but given the unique dynamics in states—especially the presence of permanent majority parties in the states where such data are available—the ability to generalize to the federal level is somewhat limited.

Political contributions provide a promising way to understand the relationships between interest groups, legislators, and their parties. A large number of interest groups actively engaged in lobbying have Federal PACs, which means that using political contributions allows for the building of a large dataset of interest groups with representation from a variety of organization types. Unlike data gathered from federal lobbying disclosure reports, which record interactions, federal contribution data allow us to see statements of support.

It is important to capture the fullness of a PAC’s giving to all committees across an election cycle when assessing the relationship between group and party. PAC directors use their budgets for an entire election cycle to support their government affairs department’s legislative strategies. For this reason, for each group, I include all contributions across an election cycle, including hard money, independent expenditures, contributions to re-elects, leadership PACs, and party committees. This allows me to capture the full picture of interest group party preferences. Hard dollar contributions are the disbursements PACs make directly to FEC-registered committees, including candidates for office. These contributions are subject to contribution limits and are disclosed by PACs in regularly filed reports to the FEC. PAC contribution totals by party, which are often used in annual reports to PAC members to communicate a PAC’s partisan or bipartisan posture, are a public signal to interest group members and elected officials alike about the legislators with which the group hopes to build relationships. Thus it is easy to ascribe partisan leanings toward patterns of hard money contributions. Independent expenditures are direct campaign expenditures that PACs and other entities make on behalf of candidates for office. The expenditures typically take the form of advertisements or direct mail and expressly advocate for or against a candidate for office. While these contributions must be disclosed to the FEC, information about the funders for these contributions tends to be more opaque. While PAC hard dollar contributions are often used to secure access to incumbents, independent expenditures are used to influence election outcomes.

Since groups use independent expenditures to run ads that advocate for or against a candidate, I expect that such spending will reveal information about an interest group’s party preferences that might otherwise remain unknown. For example, the National Association of Realtors gives independent expenditures to candidates based on recommendations by volunteer-led advisory groups at the local level. These advisory groups tend to be led by Republicans, which means that a majority of independent expenditures from the National Association of Realtors go to Republicans. As a result, even though the National Association of Realtors gives evenly to the two parties through its hard dollar contributions, the group’s independent expenditures lean Republican. Taking both hard dollar and independent expenditure contributions into account allows us to see a fuller picture of the interest group—an access-oriented association that emphasizes building relationships with legislators from both parties but leans Republican due to the party affiliation of the group’s local leaders. More generally, I expect these two types of contributions to provide different information about group preferences. Taken together, the contributions can provide greater insights about a group’s party proximity.

Evaluating the Party Proximity Index

To measure an interest group’s distance from the political parties, I have developed a novel measure called Party Proximity Index (PPI), which plots interest groups on a continuous scale from −1 to 1. Groups closest to the Democratic party have a PPI approaching − 1. Groups closest to the Republican party have a PPI approaching +1. Groups with a score approaching 0 are equidistant from both parties. Since the hypotheses in this project involve the level of partisanship regardless of party, I use Folded PPI Index to test hypotheses. This variable uses the absolute value of PPI to determine the group’s distance from either the Democratic or Republican party.

Measuring party proximity

To develop PPI, I use data compiled from the FEC. For each of the 2040 interest groups in the dataset, I select PAC contributions to any committee with a partisan affiliation, which includes all candidate committees, leadership PACs operated by current candidates for office, and party committees. To execute this task, I use bulk data available from the FEC and select all contributions from political action committees during the 2015–2016, 2017–2018, and 2019–2020 election cycles, including PACs, independent expenditors, and Super PACs. To isolate interest groups that are engaged in political contributions nationally, I omit from the dataset party committees, individual contributors, committees controlled by a single federal officeholder, committees that contribute to a single candidate for office, and committees that represent subnational organizations. I then identify the interest group controlling each committee and consolidate all contributions from committees controlled by that interest group into a single unit of analysis. For example, if an interest group maintains a Federal PAC, a Super PAC, and an electioneering committee, contributions from all of those committees are aggregated into a single record in order to analyze behavior across all of the interest group’s committees. Independent expenditures are more difficult to trace than hard dollar contributions to candidate committees. All independent expenditures—direct mail or advertisements for example—must be reported to the FEC. This means that when an organization maintains its own Super PAC, as NARAL does with the NARAL Freedom Fund, it is possible to use FEC data to know the candidates an organization supports or opposes through its independent expenditures. These independent expenditures, which are available for bulk download from the FEC, are included in my dataset.

For each interest group, I calculate the total dollar amount of PAC contributions to committees affiliated with each party during an election cycle. Since independent expenditures involve contributions supporting or opposing an identified candidate for office, I isolate the contributions made in opposition to a candidate and switch the party for those contributions (contributions made opposing a Democrat are coded as Republican and vice versa). From those totals, I determine the percent of contributions made to Republican committees. I subtract the percent Republican contributions in the cycle from the percent Republicans in Congress for the cycle in which the contribution was made in order to compare the group’s contribution ratio to party ratio in Congress.

Comparing these two ratios is an important feature of the measure since the party ratio is what many groups use as a baseline when planning their PAC budgets. For example, if Republicans hold 60% of seats in the House and Senate during an election cycle, a nonpartisan group would give in ratios equal to the party ratio in the body by giving 60% of their PAC contributions to Republicans. If the ratio shifts to 40% Republican in another election cycle, a nonpartisan group would give in ratios equal to the party ratio in the body by giving 40% of their contributions to Republicans. Without comparing the party giving ratio to the party ratio in Congress, groups might appear to be swinging from favoring one party to the other when in reality, they are acting strategically with respect to the party ratios in Congress.

Since the maximum and minimum difference values will fluctuate depending upon the percent Republicans in Congress during a cycle, I rescale the variable to ensure consistent maximum and minimum values. To maintain a consistent midpoint of 0 and consistent end points of -1 and 1, I rescale the difference by dividing positive values by the absolute value of the maximum value and dividing negative values by the absolute value of the minimum value. To check that rescaling did not affect results, I also test all hypotheses using the un-rescaled PPI variable. Substantive conclusions do not change.

I use the average rescaled differences from the most recent three election cycles (2015–2016, 2017–2018, and 2019–2020) to calculate PPI. Using three cycles smooths out some of the variations that can happen in reaction to events in a particular Congress. For example, the events of January 6, 2021, will temporarily cause some PACs to give to fewer Republicans even when those PACs do not necessarily favor Democrats (Doyle 2021). Using the average across three election cycles, which will incorporate new contribution data every two years, also allows for party affiliation to change gradually over time, as has been suggested in party literature (Victor and Reinhardt 2018). I also operationalized the variable using only data from the 2020 election cycle. Substantive conclusions do not change.

Take for example the Agricultural Retailers Association (ARA). The group’s PAC gave a 0.85 proportion of their partisan PAC contributions to Republicans during the 2020 cycle. The proportion of Republicans in the chamber for the same period was 0.47, which means that ARA PAC’s chamber difference for 2020 is 0.38. The maximum chamber difference for that period was 0.53, which represents the chamber difference for PACs that gave all contributions to Republicans. During the 2018 cycle, ARA gave 0.82 of their partisan contributions to Republicans. The proportion of Republicans in the chamber for that cycle was 0.54, which means ARA’s chamber difference for 2018 was 0.27 out of a maximum of 0.46. During the 2016 cycle, ARA gave 0.89 of their partisan PAC contributions to Republicans, while the proportion of Republicans in Congress was 0.56. ARA’s chamber difference for 2016 was 0.32 out of a maximum of 0.44. The PPIs, which represent the rescaled party differences for 2016, 2018, and 2020, are 0.75, 0.60, and 0.72, leading to a final PPI of 0.69.

Upon initial inspection, PPI scores appear to reflect what we would expect of partisan proximity and interest groups. Groups with the closest proximity to the Democratic party include EMILY’s List, Unidos, Planned Parenthood, and the American Federation of Teachers, all with PPI scores of − 1.0. Groups most proximate to the Republican party include Citizens Against Government Waste (1.0), American Conservative Union (1.0), Family Research Council (0.98), and National Rifle Association (0.98). Associations occupying the midpoint of the scale include the Auto Care Association (0.02), the American Pharmacists Association (0.00), the American College of Cardiology (0.03), and the American Veterinary Medical Association (0.01).

Some trade associations lean Republican, including groups like the US Chamber of Commerce (0.68), National Federation of Independent Business (0.96), and associations representing the building trades. Other trade associations occupy more neutral territory, like the United Fresh Produce Association (0.05) and the Toy Industry Association (− 0.02). Labor unions like the National Treasury Employees Union (− 0.89) and Communications Workers of America (− 0.97) appear to be part of the Democratic coalition. Professional associations tend to occupy the middle of the distribution, including the American Optometric Association (0.02), American Institute of Architects (− 0.04), American Medical Association (− 0.03), and National Association of Realtors (0.14).

Stepping back, however, there is much more to interest groups’ relationship to parties. The distribution for PPI index, pictured in Fig. 1, indicates that the groups are fairly evenly distributed across the scale. The modal group is very close to the midpoint of the scale. In examining groups at the poles of the scale, it appears that more groups contribute to mostly Republicans compared to mostly Democrats, although these patterns vary depending upon group type. When examining PPI score distribution by group type in Figs. 3 through 8, we can see that distributions by group types conform to the expectations laid out in the theory. Professional associations are the most likely type of interest group to maintain a nonpartisan posture. Firms and trade associations are also more likely to be nonpartisan, while labor unions, issue advocacy nonprofits, and electoral organizations are more likely to be partisan.

The mean PPI score is 0.19, which means the average group gives fairly evenly to Democrats and Republicans with a Republican lean. The median PPI score is 0.19, which indicates a fairly even distribution with few outliers. Perhaps most interesting is that the standard deviation for PPI score is 0.52, which means 68 percent of values on the scale fall between − 0.33 and 0.71. Theoretically, this is significant since a large majority of interest groups maintain distance from both political parties. The mean Folded PPI score is 0.44. The median score is 0.37. The standard deviation is 0.34, meaning that 68 percent of groups fall within 0.10 and 0.78. In the distribution of the PPI folded variable in Fig. 2, groups with greater distance from the two political parties represent the modal value, with a significant number of groups clustered at the maximum of the range as well.

Comparing PPI to existing measures of interest group ideology

One important validation step is comparing PPI score with existing measures for interest group ideology. Since partisanship and ideology are related but separate concepts, I expect an interest group’s ideology to predict its PPI score with some theoretically significant exceptions for trade associations, firms, and labor unions. In order to test this expectation, I compare PPI scores to IGScores, a measure developed by Crosson, Furnas, and Lorenz using public positions taken on issues by 2510 interest groups (Crosson et al. 2020). Of the 2510 records in the IGScores dataset and 2040 records in the PPI dataset, 637 appear in both datasets. This indicates that there is a fair amount of overlap in the datasets, but also that focusing on different data sources leads to identifying a more comprehensive set of interest groups. Notably, 72.35 percent of organizations that take positions on issues do not make federal contributions to candidates, and 68.77 percent of organizations that make federal contributions to candidates do not take positions on issues. These differences suggest that there is a potential to use both datasets to have a better understanding of the interest groups universe in the US.

Comparing the 637 groups that have both IGScores and PPI scores, there is a strong correlation between the two scores (Pearson’s R = 0.61). Identifying the similarities and differences in the two scores is best accomplished by visualizing the comparison between IGScores and PPI scores, broken out by group type. Since electoral organizations do not lobby, there are no such groups with both PPI and IGScores. In Fig. 10, we can see that there is a strong relationship between IGScore and PPI score among issue advocacy nonprofits. This conforms with the expectation that most issue advocacy nonprofits align with the party that has adopted its issue into its party platform (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9).

As illustrated in Fig. 10, professional associations are the most likely interest group type to maintain nonpartisan status. However, among professional associations with more partisan PPI scores, there is a strong relationship between the two measures. This relationship reinforces the expectation that professional associations will have nonpartisan policy goals, but will also be responsive to demands to match member partisan preferences in order to maintain a membership that is relatively sensitive to political disagreements.

The relationship between IGScore and PPI score is less direct with firms, trade associations, and labor unions. Firms and trade associations have similar patterns, with many groups clustered in the center right of both distributions, which is something that Crosson et al. (2020) also discussed. However, observing the trend lines for firm and trade association panels in Fig. 10, we can see that as IGScores increase, the values for PPI score remain relatively stable. I argue that this is due to the tendency for companies and trade associations to use access-oriented strategies to accomplish their policy goals. Unlike professional associations, which must be sensitive to members’ party identities, trade associations and firms are more insulated from these pressures due to the nature of members’ relationships with the organizations and thus are more likely to use a bipartisan strategy that will provide access to decision-makers regardless of which party is in power.

Labor unions’ IGScores and PPI scores are predictably located in the left/Democratic quadrant for both distributions. However, the trend line illustrates that as IGScores move from the most ideologically liberal to a more centrist policy approach, PPI scores remain strongly Democratic. This trend supports the expectation that while some labor unions might have more or less liberal policy platforms than others, labor unions will remain reliably Democratic due to the party’s support for collective bargaining rights. Overall, the relationship between IGScores and PPI scores, when examined by group type, supports the expectations laid out in the current theory and suggests that there is utility in understanding both an interest group’s ideology and its partisanship, since these two dimensions measure separate but related concepts.

Comparing PPI to existing measures of ideology

In the preceding section, I establish face validity of PPI. Establishing that PPI correlates with other indicators of partisanship will provide an objective way to evaluate the measure. To accomplish this task, I test two hypotheses. The first relates to political endorsements and scorecards. As discussed in Grossman and Dominguez (2009), the candidates a group endorses can provide insights about the party with which the group is aligned. Nonpartisan groups have moved away from endorsements and, scorecards, which serve as proxy endorsements. Consequently, I expect that groups that endorse or publish scorecards will be more partisan than nonendorsing or scorecard producing groups.

The second comparison relates to the likelihood of different types of groups being incorporated into political parties. Scholars have identified issue advocacy nonprofits and labor unions as the types of groups most likely to have been incorporated into party coalitions (Karol 2019). Scholars also suggest that business-related groups are likely to engage in an incumbent-centered strategy (Wright 2002). Since firms, trade associations, and professional associations use access-oriented strategies to accomplish their organizational and public policy goals, I expect those groups to be less partisan than labor unions and issue advocacy nonprofits. Many trade and professional associations intentionally balance their political giving in order to appease members and secure relationships on both sides of the aisle.

Variables

Endorsements/Scorecards: To test the first hypothesis, I use data aggregated by Project Vote Smart (PVS) and collected from interest group websites to create an indicator variable for groups that endorse candidates for office or publish scorecards (Vote Smart API 2021). PVS is a common source of scorecard and endorsement data (McKay 2008; Koger et al. 2009; Broockman and Skovron 2018). Of the 2040 groups in the dataset, 221 of the groups endorse or publish scorecards (10.83%).

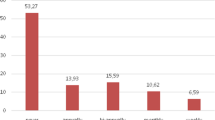

Group Type: Since the second hypothesis predicts that interest groups of certain types will engage varying partisan behavior, I created a variable for interest group type. I used information gleaned from each group’s website to assign groups to one of six types: labor union, trade association, professional association, firm, issue advocacy nonprofit, and electoral organization. I use the terminology issue advocacy nonprofit in lieu of single-issue group, which is language used by earlier scholars, because some groups are active in a variety of issues. I include the electoral organization group type in the dataset because of the relative prevalence of organizations that do not lobby or take positions on legislation, but get involved financially in electoral campaigns—EMILY’s List is a prominent example of such an organization. All groups fell cleanly into one of the six categories based on the following set of criteria. The dataset includes 97 issue advocacy nonprofits (4.75%), 66 labor unions (3.23%), 93 professional associations (4.56%), 416 trade associations (20.37%), 1236 firms (60.53%), and 132 electoral organizations (6.46%). The prevalence of firms is consistent with the long literature on the dominance of economic/business interests in the interest group universe (Schlozman 1984, 2010). A visualization of this distribution is provided in Fig. 9.

Results

As observed in the previous section, groups that endorse or publish scorecards are more likely to be partisan than those that do not engage in those activities. Therefore, if PPI is a valid indicator of an interest group’s proximity to one of the political parties, then Folded PPI score will be positively correlated with the indicator variable for political endorsements and scorecards. I test this hypothesis using OLS regression with Folded PPI score as the dependent variable and the indicator variable for endorsements/scorecards as the independent variable.

OLS results in Model 1 of Table 1 indicate that endorsements and scorecards have a positive and statistically significant relationship with Folded PPI (p < 0.05). The model predicts groups that do not endorse or publish scorecards will have a mean Folded PPI score of 0.40, while groups that endorse will have a mean Folded PPI score of 0.83. In other words, moving from nonendorsing to endorsing results in an increase of more than one standard deviation in Folded PPI score. Referencing Fig. 11, which plots predicted PPI scores for both endorsing and nonendorsing groups, we can see groups that endorse or publish scorecards have PPI scores among the most partisan of groups in the dataset, while groups that do not endorse are more likely to be politically neutral or lean slightly toward a party.

I test the second hypothesis using OLS regression with Folded PPI score as the dependent variable and organization type as the independent variable. Since it is conventional wisdom among interest group practitioners that professional associations, trade associations, and firms tend to be less partisan than labor unions and issue advocacy nonprofits, I expect to see higher Folded PPI scores among labor unions, issue advocacy nonprofits, and electoral organizations and lower Folded PPI scores among trade associations, professional associations, and firms.

The results in Model 2 of Table 1 indicate that the relationship between organization type and Folded PPI score is positive and statistically significant (p < 0.05). The relationship is also substantively significant. The baseline value for organization type is professional association, which the model predicts would have a Folded PPI score of 0.26—the least partisan of all organization types. Trade associations are predicted to be slightly more partisan but still fairly neutral with a predicted Folded PPI score of 0.38. Firms have a score similar to trade associations, with a predicted Folded PPI score of 0.39. Labor unions are expected to have a closer proximity to one of the parties with a predicted Folded PPI score of 0.78. Issue advocacy nonprofits are predicted to be the most partisan type of group, with a predicted Folded PPI score of 0.83. Electoral organizations have a similarly high predicted Folded PPI of 0.80. In Fig. 12, we can see that trade associations, professional associations, and firms have lower predicted Folded PPI scores than issue advocacy nonprofits, labor unions, and electoral organizations.

Model 3 in Table 1 includes a full model with variables for endorsements/scorecards and organization type. The relationship between party proximity and endorsement practices remains statistically significant, as does the relationship between party proximity and organization type (p < 0.05). With the results of this model, we can see that the most partisan type of group is an electoral organization that endorses or produces scorecards (predicted Folded PPI score of 0.93, which approaches the top of the range of values), while the least partisan type of group is a professional organization that does not endorse or produce scorecards (Folded PPI score of 0.22, which is relatively neutral). This model has an adjusted r-square of 0.44, which indicates the best fit compared to the other models. I expect that this better model fit is due to Model 3 better explaining the variation in labor unions and trade associations, both of which have a good amount of variation in Folded PPI score. By isolating the labor unions and trade associations that produce scorecards and endorse, we can better predict the partisanship of those types of groups.Footnote 1

Conclusion

The model results provide evidence that PPI is a way to conceptualize an interest group’s proximity to one of the two major US political parties. Groups that engage in partisan activities like endorsements and issuing public scorecards are likely to have highly partisan PPI scores. Labor unions, issue advocacy nonprofits, and electoral organizations also have highly partisan PPI scores. Evidence suggests that trade associations, professional organizations, and firms are the least partisan groups, although some trade associations lean toward one party or the other for strategic reasons. Ultimately, these findings support the theory that groups go about accomplishing their policy goals in different ways—some by affiliating with a political party and others by building relationships with policymakers on both sides of the aisle.

The findings in this paper provide opportunities for future extensions. Given the primacy of policy goals behind a group’s partisan lean, we might use PPI score to learn more about lobbying behavior in groups with different partisan dispositions. I expect that including PPI in models of interest group decision-making will shed additional light on the strategic decisions of interest groups at different positions on the PPI scale. Scholars can use PPI scores across multiple election cycles to track possible realignment among business groups—a nascent trend that has been identified in media accounts of corporate involvement in politics (Ball 2021). PPI score can also help us understand the strategies groups use to mobilize members. Given that interest groups are prevalent and influential in the policymaking process, there are many questions to be explored, and PPI offers a new and unique way to investigate those questions.

These findings are promising, but there are some limits to using PPI score to impute partisanship. We are unable to assign scores to groups that do not make federal political contributions. So while the American Farm Bureau Federation, for example, is an influential group in the area of agriculture policy, we are unable to assign a PPI score to the group since it has no Federal PAC. However, PPI provides insights into a variety of other groups that are not present in other datasets including the Farm Credit Council, the American Pharmacists Association, and the American Maritime Officers Union. Given the complexity of the interest group landscape, it may be that multiple measures/approaches are necessary to capture the totality of interest groups involved in policymaking and politics.

Second, the focus on contributions means that this measure may produce different results during different campaign finance regimes. We might expect different behavior, for example, before passage of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002, which banned interest groups from making soft money contributions to national party committees, or prior to the Citizens United decision, which loosened regulations on independent expenditures. For this reason, additional study is needed to understand how PPI might perform over time.

Notes

A model that includes a variable for PAC size has no statistically significant effect on the effect of organization type and endorsement practices on party proximity.

References

Adamy, J., and P. Overberg. 2019.‘Doctors, once gop stalwarts, now more likely to be democrats. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/doctors-once-gop-stalwarts-now-more-likely-to-be-democrats-11570383523

Baker, A.E. 2018. Are federal PACs obsolete? Interest Groups and Advocacy 7 (2): 105–125. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-018-0034-4.

Ball, M. 2021. How Big Business Got Woke and Dumped Trump. Time Magazine. https://time.com/6111845/woke-big-business-dumps-trump/.

Barber, M., and M. Eatough. 2020. Industry politicization and interest group campaign contribution strategies. Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1086/707493.

Bawn, K., et al. 2012. A theory of political parties: Groups, policy demands and nominations in American politics. Perspectives on Politics 10 (3): 571–597. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592712001624.

Bonica, A. 2013. Ideology and interests in the political marketplace. American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 294–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12014.

Bonica, A. 2014. Mapping the ideological marketplace mapping the ideological marketplace ideology. American Journal of Political Science 58 (2): 367–386.

Broockman, D.E., and C. Skovron. 2018. Bias in perceptions of public opinion among political elites. American Political Science Review 112 (3): 542–563. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055418000011.

Business Roundtable (2019) Statement on the purpose of a corporation.

Center for Responsive Politics (2022) Republican Majority for Choice Summary, Open Secrets.

Clark, P.B., and J.Q. Wilson. 1961. Incentive systems: A theory of organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 6 (2): 129–166.

Cohen, M., et al. 2008. The party decides. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cox, G., and M. Mccubbins. 1993. Legislative Leviathan: Party Government in the House. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Crosson, J.M., A.C. Furnas, and G.M. Lorenz. 2020. Polarized pluralism: Organizational preferences and biases in the American pressure system. American Political Science Review 114 (4): 1117–1137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000350.

Doyle, K.P. 2021. ‘PAC giving to GOP Dives ascompanies retrench after Jan. 6 Riots’. Bloomberg Government. https://about.bgov.com/news/pac-giving-to-gop-dives-as-companies-retrench-after-jan-6-riots/#:~:text=6%20Riots,-Contributions%20to%20congressional&text=Political%20action%20committee%20contributions%20to,6%20Capitol%20riot.

Ellis, C., and J. Stimson. 2012. Ideology in America.

Fouirnaies, A., and A.B. Hall. 2014. The financial incumbency advantage: Causes and consequences. Journal of Politics 76 (3): 711–724. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381614000139.

Grossmann, M., and C.B.K. Dominguez. 2009. Party coalitions and interest group networks. American Politics Research 37 (5): 767–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X08329464.

Karol, D. 2009. Party position change in American Politics: Coalition management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karol, D. 2015. Party activists, interest groups, and polarization in American Politics. In American gridlock: The sources, character, and impact of political polarization, ed. J.A. Thurber and A. Yoshinaka, 68–85. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karol, D. 2017. ‘Parties and leadership in American politics. In Leadership in American politics, ed. J.A. Jenkins and C. Volden, 141–166. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt207g569.9.

Karol, D. 2019. Red, green, and blue: The partisan divide on environmental issues. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Koger, G., S. Masket, and H. Noel. 2009. Partisan webs: Information exchange and party networks. British Journal of Political Science 39 (3): 633–653. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123409000659.

Krimmel, K. 2017. The efficiencies and pathologies of special interest partisanship. Studies in American Political Development 31 (2): 149–169. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898588X17000104.

Lacombe, M.J. 2019. The political weaponization of gun owners: The national rifle association’s cultivation, dissemination, and use of a group social identity. Journal of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1086/704329.

Lacombe, M.J. 2021. Firepower: How the NRA Turned Gun Owners into a Political Force. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

LaPira, T.M., and H.F. Thomas. 2017. Revolving door lobbying: Public service, private influence, and the unequal representation of interests. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Mccarty, N.M., and K.T. Poole. 1998. ‘An empirical spatial model of congressional campaigns author (s): Nolan M . McCarty and Keith T . Poole Published by : Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Society for Political Methodology Stable. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25791581 An Em’, 7, pp. 1–30.

McKay, A. 2008. A simple way of estimating interest group ideology. Public Choice 136 (1–2): 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-008-9281-2.

McKay, A. 2010. The effects of interest groups’ ideology on their PAC and lobbying expenditures. Business and Politics. https://doi.org/10.2202/1469-3569.1306.

Olson, M. 1965. The logic of collective action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Robezneiks, A. 2021. Solid house majority backs stopping medicare physician pay cliff. New York: American Medical Association.

Salisbury, R.H. 1992. Interests and institutions: Substance and structure in American politics. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Schlozman, K.L. 1984. What accent the heavenly chorus? Political equality and the American Pressure System. Journal of Politics 46 (4): 1006–1032.

Schlozman, Kay L. 2010. Who sings in the heavenly chorus? The shape of the organized interest system. In L. Sandy Maisel, Jeffrey M. Berry, and George C. Edwards (eds), The oxford handbook of american political parties and interest groups (2010; online edn, Oxford Academic, 2 May 2010), https://doi-org.proxyum.researchport.umd.edu/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199542628.003.0022. Accessed 5 Aug 2023.

Snyder, J.M. 1992. Long-term investing in politicians; or, give early, give often. Journal of Law and Economics 35 (1): 15–43.

Thieme, S. 2020. Moderation or strategy? Political giving by corporations and trade groups. Journal of Politics 82 (3): 1171–1175. https://doi.org/10.1086/707619.

Victor, J.N., and G.Y. Reinhardt. 2018. Competing for the platform: How organized interests affect party positioning in the United States. Party Politics 24 (3): 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068816678888.

Vote Smart API. 2021. Project Vote Smart.

Walker, J. 1991. Mobilizing interest groups in America. Mobilizing Interest Groups in America. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.12845.

Wright, J.R. 2002. Interest Groups and congress: Lobbying, contributions, and influence. New York: Pearson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author is an employee of an organization that has interest groups as members.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Meli, A.D. Party people? Measuring interest groups’ proximity to political parties. Int Groups Adv 12, 364–387 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-023-00193-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-023-00193-4