Abstract

Sweden has actively pursued internationalisation policies at national level, in parallel to the pursuit of internationalisation strategies of individual universities. This article focuses on university responses towards internationalisation, and the interplay between external higher education environments and institutional positioning. We draw on empirical qualitative research in two of Sweden’s largest universities, to examine institutional responses to internationalisation, expressed through documentary material and interviews with 32 senior leaders. Our findings suggest that the global research environment acts as a strong discursive driver for internationalisation actions, manifested in the strategic partnerships pursued by the two institutions. An equally powerful driver, is the national higher education sector as a context of constant comparisons and competition but also as a source of collaborative learning and exchange. The two universities exhibit strategic autonomy in their reading of the internationalisation imperative, and in constructing their actions and responses, although these are significantly framed by size and geography. In the Swedish higher education landscape, these two dimensions constitute a constraining physical and discursive context, underpinning the links between a global, internationalised environment, and the universities’ self-image and positioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The last 20 years have seen rapid transformations to the environment of higher education institutions (HEIs) across Europe and beyond, with cross-border circulation of ideas, knowledge production, people and practices. Engaging with global discourses and models of teaching and research is now relatively easy, with technological solutions allowing policy learning, shifting patterns of academic prestige, exchange of ideas, and research dissemination (Kwiek 2020). At the same time, these transformations bring about pressures on individual institutions and whole nations to appear in the increasingly institutionalised and highly questionable university rankings (Decuypere and Landri 2021; Marginson and van der Wende 2007), as a signal of excellence and competitiveness in the national and international arenas (Elken et al. 2016).

The landscape of intensified international interconnectedness and the increasing expectation that universities will become global players, turn national and institutional internationalisation policies into instruments that drive competition between universities within the same country and beyond (de Haan 2014; Hazelkorn 2018). There are of course exceptions, visible in patterns of cooperation, more commonly associated with European HE systems (Marginson and Wende 2007), or, in more politicized reactions against globalization and towards shifts to nationalism (Tange and Jæger 2021). The higher education literature acknowledges the role of national and organisational cultures in mediating university positions towards globalization and internationalisation (Agnew and van Balkom 2009; Burnett and Huisman 2010; Johnstone and Proctor 2018), and in designing strategies that account for the different contexts that filter globalized discourses (Buckner 2019; Iosava and Roxå 2019).

In Sweden, there is a renewed interest and focus on internationalisation as an important objective for the higher education sector. This is evidenced by the publication of a commission inquiry outlining the vision of the country as a knowledge nation (SOU 2018: 3; SOU 2018: 78), and by a recent revision of the Higher Education Act (SFS 1992: 1434, 1 kap.5§) to strengthen universities’ commitment to international activities, in order to strengthen the quality of education and research and to contribute to national and global sustainable development (c.f. Prop. 2020/21:60, p.179ff).

Sweden is a particularly interesting country for internationalisation studies. It has a highly developed education system, under conditions of a strong and open economy, and has been extending its ambitions in the global higher education sphere (SOU 2018: 3). The rationales for engaging with it are different to those in many highly internationalised HE systems, since the process is not primarily driven by the commercialisation of student recruitment. Still, Swedish institutions face reputational pressures that emanate from national and international contexts and emphasise particular attributes and standards (Börjesson 2005; Forstorp and Mellström 2018), often defined by research performance. However, despite the general scholarly interest in internationalisation and higher education, institutional responses to and filtering of internationalisation still remain under-researched in the Swedish HE policy field. The positioning of universities towards internationalisation, and the ways in which institutions engage with related discourses, illustrate how they perceive the value of internationalisation and the benefits for the institution (Pinheiro et al. 2014), as well as their projected profile and image in order to gain legitimacy, status, or competitive advantage (Gavrila and Ramirez 2018; Silander and Haake 2017). This article focuses on the interplay between external higher education environments and internationalisation as a university response. Our aim is to explore how universities within the same national space adopt internationalisation discourses and respond to particular contexts. The key questions for this study are (1) how do Swedish universities interpret the environment within which they operate in relation to internationalisation? and, (2) how do they position themselves and construct particular levels of ambition towards internationalisation?

The Swedish HE System and Internationalisation Policies in Brief

As in other Scandinavian countries, the Swedish HE system follows a mass public model, supported by high government funding and having comparatively high enrolment rates. There is overall political consensus on the important economic role played by universities in combination with an orientation to promote social justice and mobility, in line with general traits of a social democratic welfare state regime (Bleiklie and Michelsen 2019; c.f. Nokkala and Bladh 2014). There are almost 50 HEIs in Sweden and 17 of them are Universities which are more research intensive than the generally smaller/more specialised University Colleges. As a result, they get larger government funded grants since they carry out most of the research activities. All HEIs also receive public funding based on the number of enrolled students and students’ achievements, with the amount per-student differing according to subject area. For the students, HE is free of charge but in 2011 tuition fees were introduced for non-EU/EEA citizens. This initially meant a sharp decrease in incoming non-EU students even if the share has gradually increased. In contrast to Anglo-Saxon countries where fees are a substantive economic incentive, Swedish HEIs have a limited financial interest to increase the intake of fee-paying students because the fee only covers the actual cost for tuition (SOU 2018:3). Still, HEI funding is connected to numbers of students, so there is a general incentive for HEIs to attract students (domestic or international) up to the government-set financial cap.

Public HEIs base their work on an agreement with the government via the Ministry of Education and Research but have extensive autonomy in determining the organisation of work, internal resource allocation and staffing. The 1993 HE Act was designed to offer more local autonomy and flexibility, and decisions on planning and content of study programmes were transferred from the state and its agencies to universities. Still, the responsibility to determine the goals for degrees remains with the government and parliament (SFS 1992:1434). Recent reforms, similar to those of other EU/OECD countries, have targeted HEI internal management aiming to achieve increased efficiency and improved outcomes. The so-called autonomy reform from 2011 is one example (c.f. Puaca 2020). While more discretion was granted to universities, the reform also increased demands for quality assurance and results-based management, including audits and intensified national evaluations (Segerholm et al. 2019).

Internationalisation is not a new policy issue in Swedish HE. In the 1970s, it was a topic of several reports from the national agency for HE, and the 1977 HE Act included an aim to promote understanding of international contexts—a goal that remained in the revised legislation from 1993. Joining the EU and Erasmus Programme, the 1990s boosted internationalisation efforts in the sector. In addition, the 2000s and the Bologna process, initiated a number of adjustments and reforms. In 2005, the first explicit internationalisation strategy, clearly oriented towards Europe, was endorsed by the Parliament (Govt. Bill 2004/05:162). This strategy was largely reconfirmed in the 2009 Bill “Knowledge without borders-higher education in the era of globalisation” (Govt. Bill 2008/09:175). A decade later, a more thorough revision was initiated and in 2018, a new national strategy was proposed. This work had, as we shall expand on more below, an explicit comprehensive approach to defining internationalisation (SOU 2018:3).

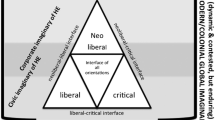

University Environments and Positionings

University responses to internationalisation expectations, and their own positioning, depend on (a) the nature of the environment they operate in, and their interpretation of that environment, and, (b) how they view ‘themselves’ and their possibilities for action. It is the interplay between these two considerations that define the strategic reading of particular institutions in terms of who they are, where they are, what they can aim at. These ideas are rooted in neo-institutional views of organisations that respond to environmental changes through internal processes of translation and mediation. These responses are filtered through organisational histories, identities, and norms of sub-systems such as academic faculties and departments, as well as the intentionality of individual actors (March and Olsen 2006; Scott 2013). The degree of matching of external expectations and pressures (such as internationalisation policies in the HE field) to organisational dynamics, goals and directions, decides to a large extent which of these external expectations will be adopted, and in what form. Scott (2013) saw organisations as affected by their environments but at the same time as capable of strategic and creative responses to external influences, an observation particularly pertinent for universities that deal in the production and dissemination of knowledge, through the work of highly autonomous professionals. We elaborate on these points further.

The Environment

For HEIs the operational environment consists of a range of discursive, legal, policy and contextual settings that steer and regulate university missions and practices, some by limiting options, others by furthering horizons for strategic positioning. First, as a discursive framework, internationalisation presents a rich external global environment for universities, full of information and ideas about other countries’ and institutions’ approaches to teaching, research and operational activities. Universities face pressures to adapt in processes that involve emulating others, especially those they consider similar to themselves (Labianca et al. 2001), responding to projected ‘university identities’ and images of success (Gioia et al. 2013), or, engaging with either superficial (re)branding or more systematic structural change (Stensaker 2007). Second, in addition to international developments, the environment for universities includes national regulative frameworks (Shattock 2014) defined primarily by governments through legislation, inspections and financing, but also government agency work that relate to issues of quality, research performance and student outputs (Neave 2000; Segerholm et al. 2019). Within this national policy space, and depending on the nature of governance and financing of the sector, several HEIs offer diverse provision in terms of education, research, and connections to local settings. This diversity can lead to different degrees of vertical diversification in relation to reputation, quality and selectivity (Teichler 2015). Finally, in Sweden as in many European settings, governments expanded higher education provision in a process of ‘geographical decentralisation’ intending to facilitate access to HE and develop various regions beyond ‘the traditional university cities’ (Kyvik 2009: 61). This opens up interesting questions in relation to how universities beyond the usual national ‘centers’ for higher education construct their profile and project ambitions in the local, national and international arenas of action.

Institutions and Positioning

How individual universities respond to external environments depends not only on the national policies and higher education landscape but also on several dimensions connected to the organisation’s own characteristics (Barbato et al. 2021). Universities often enjoy high degrees of autonomy in relation to their governance, management and finances, and hence, a considerable scope for interpreting internationalisation discourses and designing strategies according to their own institutional needs (Luijten-Lub et al. 2005), certainly the case in Sweden (c.f. Silander and Haake 2017). As such, they have agency to shape their profile, strategic approaches, and horizons of action, in relation to internationalisation (Thoenig and Paradeise 2016). In this article, we adopt Fumasoli and Huisman’s (2013) definition of ‘positioning’ as a ‘process through which universities try to locate themselves in specific niches within the HE system’ (p.164). This process captures the ‘relation between intentionality and environmental influence’ (ibid., 164) and is shaped by the balance that universities keep between the pressures to respond to outside influences (of a global, legal, or policy nature), their own core tasks, as well as what other universities are doing.

The recent Swedish inquiry on internationalisation in universities (SOU 2018:3) endorsed Hudzik’s (2011) concept of ‘comprehensive internationalisation’ that refers to infusing ‘international and comparative perspectives throughout the teaching, research and service missions of HE’ and permeates all aspects of university ‘leadership, governance, faculty, students, academic service and support units’ (in SOU 2018:3, p. 68). Given the complexity of universities, and the multiple dimensions of internationalisation as an organisational objective, it is important to recognize that there is a multitude of actors within universities that contribute to the interpretation of these dimensions and their embedding in the governance and missions of the institution (Chou et al. 2017). In addition, there are different stakeholders involved in the HE policy process at national and sub-national levels (Fumasoli 2015), not all pursuing the same priorities. Different or even conflicting agendas across these actors and stakeholders may result in several approaches to internationalisation and its coordination. The high degree of university autonomy, however, means that they are actors that ultimately decide how to define internationalisation, design strategies, implement and evaluate them. This perspective emphasises what Barbato et al. (2021) call ‘the organisational dimension in university positioning’ (p. 1356), an acknowledgement of the significance of organisation structures, resources, identities and location within the sub-national university scene, in strategic decision making.

The Study

We follow a qualitative, exploratory methodology in the form of a case study (Yin 2018) of universities’ interpretation of their external environment and positioning in relation to internationalisation. Drawing on the literature, our proposition is that the size, academic profile, and location of universities, shape their position towards internationalisation (Agnew and van Balkom 2009; Burnett and Huisman 2010). This principle underpins our selection of two universities, largely following a ‘most similar cases’ approach (Berg-Schlosser and De Meur 2009), where the two cases share a similar profile within the overall Swedish HE context in relation to size and (mostly) comprehensive education and research profiles, in different geographic locations. Of course, we are aware that ‘similarity’ between two large and complex organisations is always approximate. Our research adopts an iterative process of data collection and analysis in the two cases, in order to add in-depth knowledge on how the university responses to internationalisation are framed, and how they contribute to the emergence of similarities and differences in positioning.

The universities are large public institutions, one located in the south of Sweden listed in the world’s top 200 by the QS Global World Ranking, the second, in the north, listed in the world’s top 350. Both universities are described as having a ‘very high’ research output, and a ‘strong international orientation’:

North: A 1960s university with: 39 departments, 16 research centers, 4,6 billion SEK revenue (2019) approximately 36,000 students, appr. 2000 teaching and research staff, student/faculty ratio 7

South: A nineteenth century university with: 65 departments, 15 research institutes, 5,3 billion SEK revenue (2019), approximately 39,000 students, appr. 2500 teaching and research staff, student/faculty ratio 12

For each university we collected two types of data. First, we reviewed selected strategic documents such as (i) internationalisation strategies; (ii) university-wide strategies and statements of vision; and, (iii) action plans for the different faculties (for the period 2019–2022). Second, we conducted 32 interviews with central university actors (in the positions of: vice-chancellor/deputy vice-chancellor, senior leadership at central and faculty levels, and senior administrative staff in central support, student, and internationalisation services). In our approach to the data, the perceptions of the environment within which universities operate are mediated by organisational ‘views’ as expressed in official university documents, and articulated by the senior leadership (Stensaker et al. 2020). These views in turn describe the position that the university occupies within this environment, and set the parameters for action. The interview agenda addressed the research questions in relation to the organisational approaches to internationalisation. In particular, we explored (a) the dimensions of positioning towards the national and international higher education arenas, (b) the explicit and implicit connections made between the external environment and the self-image of the university attributes, and, (c) the articulation of university ambitions regarding current and future internationalisation strategies.

The interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes, were fully transcribed, and anonymised. We analysed the material through thematic coding and the generation of abstract thematic categories that captured the meaning of the interviews (Alexiadou 2001; Hsieh and Shannon 2005). The analysed interview data were then connected to the documentary texts, and all this material was related to the research questions. The emerged high-level categories “international environment”, “national policy context—the sector”, and, “the official national policy context” capture the data and provide a structure for the presentation of the findings.

Findings

The International Environment

Linking to the Global—International Partnerships and Strategic Actions

Both universities in our study have a clear orientation towards the global environment, and its importance for the university mission. In the various official documentations of the two institutions, there are references to the United Nations Agenda 2030, and their commitment to contribute to the sustainable development goals through research, education and collaborations (Strategy document, South; Vision document, North). In several of the more operational-level documents produced by faculties and international offices, these commitments are connected to research development and capacity-building through connections with development nations, as well as with systematic quality work through strategic partnerships (South, Regional study report; North, written consultation response to SOU 2018: 78; North, Social Science Faculty Decision 2020). The documentation of both universities, combines the ‘softer’ goals of Agenda 2030, with discourses around competitiveness and the expected benefits from ‘research collaborations with emerging countries and countries with strong growth potential’ (South, Regional study report), also visible in the interview material. These responses also reveal an acute sense of the competitive nature of academic reputations in the world stage, and the need for the particular universities to maintain and increase their individual performance and international presence, mainly through establishing strategic partnerships.

For senior leaders in both universities, the twin discourses of social responsibility and competitiveness are discussed in relation to three international contexts: the regional, the European, and the global, and across (mostly) the areas of research and building partnerships.

...many countries are doing efforts to grow as knowledge nations. It’s not just the old typical countries, but many Asian and African countries push in that direction. Therefore, Sweden needs to not stand still but develop. The European Commission has been pushing for Internationalisation strategies, they asked countries to develop that …the Nordic countries are always important to look at because we are quite similar but sometimes the similarity means that we don't learn that much from each other… …the comparisons with those countries where student recruitment is very commercial, was a little bit off topic for us, that’s not what Swedish Universities want (South, 12)

The EU features as important in several interviews, primarily in connection to the Erasmus+ scheme, as well as a source of funding and research partnerships. It also features through the European Universities Initiative that has seen 11 Swedish HEIs in EU-funded university collaborations, including University South (South, 6, 7, 16).

In both institutions, there is extensive discussion of the kinds of connections with the world that they want to establish. Given their large size and diversity of research areas and education programmes, both North and South have many partnerships with international collaborators, but the nature of these is diverse, and of variable impact. The partnerships range from agreements that individual academics sign, often extended to department-level agreements (mostly with European and Nordic universities). Some of these partnerships are long-term and ‘alive’ but others are discussed as ‘dormant’. These collaborations with international academia are seen by most interviewees as valuable, bottom-up connections that are of great benefit to individuals and sometimes whole departments, but they are also seen to be ‘not stable’, ‘ad hoc’, and to ‘fade out’ when the individuals that initiated them retire or leave the university (North, 1, 11, 13; South, 1, 3). These individual/department-level collaborations will continue to be supported for individual researchers, with senior leaders in both universities viewing them in positive terms for the cumulative benefits they bring to the individuals and groups involved. But these are treated as distinct to the broader, centrally managed collaborations, instigated between universities.

University South has initiated a comprehensive strategic approach in developing international partnerships. Over the last 3 years, South has been reforming its international operations and upgrading this part of its administration, as well as reforming its policies on partnerships. As well as maintaining the several department-level agreements and collaborations, it has shifted its focus on a few core partnerships at central level that are ‘strategic’ in nature:

Pre-2012 we had a larger number of strategic partnerships but maybe not so deep. Now we decided to concentrate our resources on a deeper collaboration with fewer partners. It is much easier to work with… Strategic means you must put more effort into retaining the cooperation, and you can’t do that with 20 different universities, especially if you want the senior management to be part of it, which you should if you have strategic partnerships (South, 2)

Consolidating the many international agreements, and focussing on ‘few with central targeted money’ (South, 1) is viewed as an important step in becoming a ‘global actor’ (South, 17), although there are some voices from within the senior leadership that caution against the general nature of such agreements:

What is the added-value of choosing one university far away to collaborate? one problem with many of these organised collaborations is to define areas to collaborate... …you risk having general themes like ‘ageing population’, ‘human development’, ‘sustainability’... they are fine, but very broad. It may be scientifically not so productive. (South, 1)

Discussions on similar consolidations as in South and the creation of university-level strategic partnerships took place in the 2000s in University North, but their success varied. As a senior leader suggests “to point at certain universities from leadership level does not really work. It has to be bottom-up… which means sometimes we end up with agreements with universities that may not be the most strategic ones” (North, 3). Still, this is a continuing issue, where the problem of strategic internationalisation has been identified at the most senior level, and has been connected to the need for mapping research activities and international connections systematically:

we are looking at our many co-operations, and wonder to what extent they are strategic... if you go for strategic partnerships, you should think about why are they strategic. That would require that we know what we're doing research about. And we don't. I mean, at the faculty level the faculty knows what faculty is doing. But the university does not always know what the whole university is doing in research. Of course, we know certain researchers and areas are good. But, that is rather based on narrative evidence, than on facts… … fine to cooperate with South Africa, Japan etc. but why? (North, 2)

North currently pursues a strategy of forming a group of regionally based universities across three neighbouring countries, connected through geographical positioning (in the Arctic region), aiming to connect research and teaching levels. It also uses data platforms to map the university research activities (through publication outputs), and compare how the university profile matches that of other universities (North, 1, 2).

Despite the different stage at which the two institutions in our study find themselves in relation to strategic international partnerships, there are some interesting features that characterize their positioning towards the global HE field. These refer to questions of (a) size, and (b) geographic positioning and perceptions of ‘place’, that shape the degree of ambition towards future internationalisation goals.

Size — and the Narrative of Smallness

Size is a dimension of high significance in the representations of what is ‘feasible’ and what is ‘realistic’ in terms of setting the universities’ ambitions for internationalisation. It refers to three particular issues: the size of the country and university, the language of research and teaching, and how language connects to the research impact of the university. Interestingly, for universities that have 36-39,000 students, there is a perception amongst few of the senior leaders that their institution is ‘very small’ and not of sufficient interest to international big universities as collaborating partners (South, 12). For the purposes of international agreements, University South addresses this perceive limitation by ‘joining forces’ with two other institutions in the same city so as to form “a more complete group and be more interesting for international cooperation” (South, 12). Beyond organisational size in terms of numbers of faculties and academic staff, there is a widespread perception of ‘smallness’ in relation to language, with a distinct disciplinary dimension. For several senior leaders with a background in the social sciences or humanities, internal policies around internationalisation should be recast in the direction of internationalisation-at-home instead of shaping the university as an international player:

There are grand goals for internationalisation but we are a small minority language speaking nation in a far corner of the world... English is a second working language but we mostly do research on the Swedish context, and educate well in the Swedish context. Envisioning Swedish Universities as being hubs of internationalisation, is utopian. We could be far better at integrating (international) collaborations in research and education (North, 10)

Such critical approaches around size, also link to the usually uncontested assumption that internationalised research is high-quality research, and they come exclusively from senior leaders whose academic affiliation is in social sciences and humanities:

The Dean of the Sciences will say ‘the world is our field’ but it’s not the same for us…. If lawyers do an article in English, it’s an “overview”, that’s not research… we have to discuss what internationalisation really is. Is it always good for research? (North, 9)

These questions of the extent and nature of internationalisation regarding small countries and languages, and disciplines of a particularly national character (such as Law and Education), go against the widely shared discourses of research-knowledge universality and international relevance. To some extent, they affirm national, political and geographical boundaries around knowledge production and dissemination. They also highlight the many facets of these processes where different disciplines follow their own dynamics of internationalisation.

Finding a Niche — Geography and Positioning

The external environment and location of institutions seems to present unique and distinctive contexts that have a direct impact on internationalisation questions. First, it is interesting to note that none of our two study-universities see themselves as primarily serving the needs of the local region as a core institutional objective. Both of them have of course several local and regional connections and functions, but in their literature (mission statements, strategies, stated visions), and interviews with senior leaders there is a lack of the ‘local’ as an important dimension. The ‘self-narrative’ in both cases is one of a national and international institution, although the particular geographic location gives the two an interesting contrasting perspective. University South is positioned in the midst of the political, economic and geographic ‘center’ of the country, geographically south. Given also its large size, interviewees and strategies from this institution present an international, ‘global’ university of high ambitions, with the reputational capital necessary to extend these and to further activities, partnerships, research projects and centres, far beyond Sweden. However, next to this confident narrative and planning for future actions, exists an awareness that, at the international arena, the university needs to find the ‘right level’ of collaborations, a clear concern for both universities despite their different location:

As a university, you want to have partnership relations with good universities… on about the same level. To develop formal contacts with Stanford... They are on a slightly higher level. I mean, you need to find your friends… (South, 3)

The narrative of ‘finding our niche’ was particularly important for University North, with its spatial location adding “a function of being in a periphery” (North, 2) to the descriptions of the limits to internationalisation:

Somewhere in the 1980s we started looking more international. We can say now we are an international University... but we're not top-tier. And the question is ‘do we want to be a top-tier international University’? I would argue no, we shouldn't be. Part of that argument is geography, it will always work hard against us. In some research areas we are internationally top-tier, absolutely. But the University as a whole I think we're at the spot we're supposed to be at. To spend the kind of money required to get us to be a top-tier University, would be cost-prohibitive. (North, 11)

These centre—periphery dimensions of positioning the university towards the international environment, are also visible to some extent in the way senior leadership discuss the national context and in particular the connections between the university and other institutions in the country.

National Policy Context — The Sector

There are primarily two important national contexts and actors that the universities in our study are attentive to. These are, first, the national agencies and associations that are of direct and indirect significance to university work, and second, other universities that are seen as sources of both competition and learning. These contexts are not particularly visible in the documentary material, but feature highly in the interviews with senior leaders in both institutions.

Informal Policy Contributors

The Association of Swedish Higher Education Institutions (SUHF) is an important setting for some of the discussions around internationalisation, as an arena for national discussion and knowledge exchange. The association has an expert group on internationalisation, with an explicit assignment to share experiences across HEIs, act as a broker towards international organisations, and respond to formal and informal queries from the Ministry of Education (North, 15). Even if there are also some critical comments in the data on SUHF for ‘not having a clear agenda… or a focus on quality as a dimension of internationalisation’ other than a vague offer of supporting initiatives (North, 5), the association is still appreciated for its networking possibilities amongst individuals with a strong interest in the internationalisation agenda. In addition, SUHF provides connections to national policy making, including the Ministry and its public inquiries:

This [SUHF expert group] has functioned as an informal reference group to the Public Commission on Internationalisation… [names of investigators] have been to every meeting and had a standing item on the agenda…. They have been very open, asking for input (North 15, also member in this expert group)

Further bodies and agencies discussed by a small number of interviewees as ‘important’ are, the Swedish Council for Higher Education (UHR), in the context of facilitating the Erasmus+ programme, and for the regular network meetings amongst HEI staff working with internationalisation issues (South, 10, 11, 15, 16), STINT (Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education), and the National Student Union (SFS), seen as ‘important but peripheral’ (North, 11) because of its frequently changing mandates (North, 5). Finally, the Swedish Institute is discussed by a small number of interviewees because it attracts resources from the central government in order to ‘promote Sweden not just as a study destination but also as a knowledge nation’ (North, 5, c.f. South, 12, 13), something that was also very strongly urged in the latest inquiry on internationalisation (SOU 2018:78) that “highlighted the need for improving Sweden’s positioning in the world academic stage through international collaborations and education exports” (Alexiadou and Rönnberg 2021:10).

Competition or Learning from Others?

Of high significance for the senior leadership of both universities are direct and indirect comparisons with other universities within Sweden, a process that has practical but also reputational dimensions. For all senior leadership, but especially for individuals with internationalisation as part of their responsibilities, such comparisons include any university that may take interesting initiatives. But, a more systematic process of ‘almost informal benchmarking’ (North, 11) takes place against the few big Swedish universities that are seen to lead internationalisation efforts. The attention to what other universities do is seen as important for instrumental reasons driven by competitiveness and the desire to ‘keep up’:

Pretty much every single question I ever took with university leadership always asks how we look in benchmarkings. Why are we talking about this and others are not? (North, 5)

The importance of ‘learning from others’ (North, 3, 5, 13; South, 1, 4, 8) and trying to improve own practice is expressed at both HEIs where there are both formalized collaborations with other HEIs, as well as learning practices via informal networking and meetings across the university sector. In addition, when large universities make reforms or appoint senior leaders to develop internationalisation this attracts attention for the implications on other universities, and the whole sector. This form of learning is underpinned by a combination of competitiveness but also considerations of reforming administrative and procedural approaches to facilitate better and further internationalisation:

In Universities Y, Z, that is not just rhetoric. Within two years they have policies. They actively recruit superior quality professors and the mandates of their international office have increased big time… Everybody says the same thing but what is happening on the ground is different and it's primarily because their leadership is pushing (North, 5)

For senior leadership at faculty level, these discussions are not merely strategic at high level, but have direct implications for the operational issues of designing courses:

We had a person from University-Y who came and presented what they do… they put a lot of emphasis on the promotion of their programmes, and make it easy (for students) to think of the move to Sweden and Y. And, we discussed internationalisation-at-home what it means in practice for our education – for example, should we change our learning outcomes to include internationalisation? A lot of things are already there, for example, exposure to international research and literature – but they are not in the learning outcomes. (South, 4)

Despite the frustration from certain senior interviewees on the lack of progress, this feedback and competitive-collaborative learning from other universities is seen as one of the most important drivers for the integration of internationalisation at the operational level for research and education (North, 12, 13; South, 4, 17).

The Official National Policy Context

The legal framework within which universities operate is mentioned in connection to internationalisation, although it is repeatedly emphasized that universities have a high degree of operational autonomy. Still, within the broad parameters of the Higher Education Act and Ordinance it is pointed out that internationalisation is an expectation from the government:

If you ask me as a Dean, this is a very important issue for the whole faculty and I think that, in order to live up to the goals not only set by the university but also by the Swedish government and parliament, we have to work more systematically to reach a goal of internationalisation (North, 9)

The national goals for internationalisation have recently received political and Ministry attention, and the two public inquiry reports published in 2018 (SOU 2018: 3; SOU 2018: 78) provided an important official policy context for the senior leadership and administrators in the two institutions.

The Context of the Inquiry

In 2017, the government appointed a public commission, headed by an experienced chair, to investigate internationalisation in HE with a focus on its goals and strategies, how to include international perspectives in teaching and how to attract more foreign students. Its proposals included, amongst other things, a new national strategy for internationalising HE with setting up new national goals (SOU 2018: 3), and proposals for increasing the attractiveness of Sweden as a ‘knowledge nation’ (SOU 2018: 78). These reports provided an important focus for a number of our interviewees, especially those at the highest level (VC, and deputy rectors) and for those working specifically with internationalisation in the administration (staff working in central and faculty-based internationalisation offices). There were distinct positionings towards the reports in the interview data.

-

The Positive

The publication of the first report (SOU 2018:3) received overall positive comments from our interviewees, who saw the report as an additional ‘incentive’ for universities (South, 1, 17) to make internationalisation ‘more visible’ (South, 3, 8). There was still a certain ambiguity over the nature of recommendations, although most comments highlighted the positive views around the need for the whole sector to internationalise more, with better integration across management and operational structures, through collaborations and increased quality of education, research and partnerships (North 1, 3, 11, 15, South 2, 5, 11, 13). None of these areas of recommendations raise controversial topics for the participants in any of the two universities. The effectiveness of implementing these was however questioned, on the grounds of differing priorities within faculties:

There was a discussion in the education strategic committee but it's not one of the pressing issues, because quality assurance is so much on the agenda for us (Social Science faculty) (North, 10)

We are focussed much more on sustainability, this has been prioritized across the university… ... after sustainability, we focus on equality (North, 7)

Both universities held high-level meetings to discuss the Inquiry and its recommendations, and reported that the overall approach to internationalisation is already predominantly positive. There is, however, also the acknowledgement that beyond the senior leadership and central level actors involved in International Offices, few other University staff would be familiar with the content and recommendations of the Inquiry:

In many instances, it is like “preaching to the choir”, those already involved are those taking part in the discussions. It is hard to know if and how the inquiry spread to other people outside that immediate circle (South, 11)

In fact, several informants described that the discussions around the proposed reforms stayed at the highest leadership levels, that also were required to formally respond to the Inquiry recommendations, ‘it was not something people were reading at Department level’ (South, 2). So, this part of the external policy context is less visible for many of the other (still senior) leadership at faculty level. In both universities, it was common that persons responsible for research or teaching across faculties were not aware of the Inquiry (North, 7, 8; South, 8). It is notable also that for interviewees located in science faculties in both institutions, internationalisation is seen as ‘something natural in sciences’ (South, 1), with little need for additional attention. This relative lack of engagement at the faculty level seems to be due to a combination of practical questions of time and timing, as well as perceived relevance:

The first report I went and listened. I liked it. The second one…, someone from us went. We were expected to respond formally, but we were overloaded and decided, at (Science) faculty level, that we would not respond-it was so long. Good suggestions… but, hard to see the consequences (North, 8)

In these cases, in both institutions, the mostly positive perceptions of the Inquiry were often framed by pressures from other institutional commitments, or lack of time, and in the case of the Sciences, a questioning of the relevance of such an inquiry to the perceived already highly internationalised faculties: ‘I have not heard of it… we are so international, this is not for us’ (North, 7).

-

The Controversial

The Inquiry was not without critique. For some respondents it was not as ambitious as it could have been (North, 5,11) or did not approach the needed reforms in the sector in ways that could make them possible to implement, given the governance of Swedish universities:

[t]he whole document has 73 recommendations... not binding in any way. One recommendation was a change from “should” [“bör”] to “shall” [“ska”]. That’s pretty much dead on arrival. You cannot say “shall” to any university. So, just on principle, all the rectors said ‘no, sorry, leave it to us; we understand the weight of internationalisation’. (North, 5)

The general ‘danger’ in expressing force (“shall”) to the University sector was also identified by other interviewees, who emphasized the need for HEI autonomy over decisions and actions. In addition to this more generally held reluctance to regulation, other points regarded the lack of additional national funding for internationalisation, and not dealing with restricted migration law that negatively impacts university recruitment of staff and students:

we need a system of recruitment and possibility to hire, compatible with the international university market. And there is a lot of resistance towards that... I don't think they (government) understand what the situation is at universities. (South, 1)

A crucial point of resistance from both universities focussed on those proposals in the report seen to have resource implications, and to interfere in the way that universities decide on the allocation of their finances. The critique to how the report suggests a re-balancing of budgets to increase international student recruitment was framed primarily as political interference in terms of governance and institutional autonomy:

We dislike that. Particularly the idea that part of our surplus can be used for scholarships [for international students]… the state having suggestions on what universities should do with surplus money. So, our resistance against that is more of a principal nature. (North, 2)

These refer specifically to recommendations around the 2011 tuition-fees reform. The Inquiry addressed it following also requests from the university sector, although is suggestions were received in a uniformly skeptical way (North, 5, South, 3).

Conclusion

The research presented here reveals interesting dynamics about university responses to their external environments, and highlights the contextual and institutional character of internationalisation and its various interpretations. The way the two universities position themselves suggests a strategic approach to internationalisation shaped by how they ‘read’ the pressures and expectations of their environments, and their own particular characteristics.

First, we note that the international environment is very significant to both universities, and a strong driver for the ways in which they handle questions of internationalisation. At the same time, the Swedish HE sector and other ‘similar’ universities within, provide an equally strong context against which our two studied institutions position themselves. Both universities North and South are research-intensive, large institutions, and so, they construct internationalisation ambitions through implicit and explicit comparisons with other universities they see as similar to themselves. This is visible in the ambitious partnership strategies that seek to establish and strengthen international rather than regional or national connections. It is also manifested in their self-benchmarking against other similar research universities within Sweden, often framed in the language of learning rather than competing. In both university documents and interviews with senior leadership we observe the desire to be at the same level as other research universities (nationally and internationally), and, to do policy learning (‘what others do’) in relation to internationalisation. These are particularly relevant contexts and external environments for the HEIs in this study.

This does not mean, however, that the responses to internationalisation are the same. As other researchers find (Fumasoli and Huisman 2013; Stensaker et al. 2020), both North and South exercise significant strategic action in interpreting the international and national contexts and their positioning within. Our findings suggest that the framing of feasible and pragmatic internationalisation strategies is filtered through perceptions of size and geographic location. These two dimensions feature highly as shaping the strategic intent of the two universities. They are especially constraining North where the ‘peripheral’ location is a physical barrier that could only be overcome by what is expressed as unsustainable investments on internationalisation. University South is clearly in a better position to make strategic alliances to overcome the perceived size problems, as well as to construct discourses of global reach, although still within the (perceived) same-level niche of similar international partners. Significantly, we observe a variety of interpretations of these positionings within each institution, often filtered through a disciplinary prism. Also, there is more similarity of perspectives across the hierarchies of the institutions, than within. In both North and South, senior leadership at central levels, have more knowledge of and positive attitudes towards internationalisation (especially on research, and within the sciences) compared to the faculties, where we find more skeptical approaches towards national or university strategies to achieve it.

Our second observation refers to the relationship between the official policy context in relation to internationalisation and institutional autonomy. The national inquiry has clearly had an impact on the sector, by identifying issues and putting internationalisation firmly on the policy agenda. There is universal commitment to internationalisation discourses in official documents and most interviews, and consensual agreement about its significance. It is also clear, however, that the policy incentives and instruments provided for engaging further with internationalisation are not as endorsed across the central and faculty leadership of the two universities—although clearly more important to the staff working in international offices and some central services. Here, we observe greater diversity of positions, as well as readings of the internationalisation imperatives with more localised interpretations of what is optimal strategic action for these large and multi-faceted universities. The organisational autonomy of the university sector makes regulation of activities and priorities particularly challenging. So, more informal and voluntary national arenas for comparisons/competition and learning are crucial, to filter and respond to policy goals and demands. In fact, there is reluctance from university actors when ‘autonomy’ is perceived to be challenged. Even if all agree on the importance of internationalisation and the need for intensified institutional efforts to promote it, interviewees, in particular at strategic and high-level management, clearly prefer to develop the solutions and instruments themselves.

In conclusion, this study shows that universities’ positioning towards internationalisation is highly dependent on the balance between the external environments within which universities operate, the universities’ profile (including size, and location) and self-image, and how university actors interpret the core institutional commitments and tasks. Universities adopt a strategic approach to reading their environment and take positions that aim at differentiating them within the national higher education arena (Barbato et al. 2021; de Haan 2014).

References

Agnew, M. and van Balkom, W.D. (2009) Internationalisation of the university: Factors impacting cultural readiness for organisational change. Intercultural Education 20(5): 451–462.

Alexiadou, N. (2001) Researching policy implementation: Interview data analysis in institutional contexts. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Theory and Practice 4(1): 51–61.

Alexiadou, N. and Rönnberg, L. (2021) Transcending borders in higher education: Internationalisation policies in Sweden. European Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904120988383

Barbato, G., Fumasoli, T. and Turri, M. (2021) The role of the organisational dimension in university positioning: A case-study approach. Studies in Higher Education 46(7): 1356–1370.

Berg-Schlosser, D. and De Meur, G. (2009) 'Comparative research design: case and variable selection', in B. Rihoux and C.C. Ragin (eds.) Configurational Comparative Methods: Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Related TechniquesThousand Oaks, CA: Sage, pp. 19–32.

Bleiklie, I. and Michelsen, S. (2019) Scandinavian higher education governance — Pursuing similar goals through different organizational arrangements. European Policy Analysis 5(2): 190–209.

Buckner, E. (2019) The internationalisation of higher education: National interpretations of a global model. Comparative Education Review 63(3): 315–336.

Burnett, S.-A. and Huisman, J. (2010) Universities’ responses to globalisation: The influence of organisational culture. Journal of Studies in International Education 14(2): 117–142.

Börjesson, M. (2005) Transnationella utbildningsstrategier vid svenska lärosäten och bland svenska studenter i Paris och New York, Uppsala: Department of Education: University of Uppsala.

Chou, M.-H., Jungblut, J., Ravinet, P. and Vukasovic, M. (2017) Higher education governance and policy: An introduction to multi-issue, multi-level and multi-actor dynamics. Policy and Society 36(1): 1–15.

Decuypere, M. and Landri, P. (2021) Governing by visual shapes: University rankings, digital education platforms and cosmologies of higher education. Critical Studies in Education 62(1): 17–33.

Elken, M., Hovdhaugen, E. and Stensaker, B. (2016) Global rankings in the Nordic region: Challenging the identity of research-intensive universities? Higher Education 72: 781–795.

Forstorp, P.-A. & Mellström, U. (2018) Higher Education, Globalization and Eduscapes. Palgrave Macmillan

Fumasoli, T. (2015) ‘Multi-level governance in higher education research', in J. Huisman, H. De Boer, D.D. Dill and M. Souto-Otero (eds.) The Palgrave International Handbook of HE Policy and Governance London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 76–94.

Fumasoli, T. and Huisman, J. (2013) Strategic agency and system diversity: Conceptualizing institutional positioning in higher education. Minerva 51: 155–169.

Gavrila, S.G. and Ramirez, F.O. (2018) 'Reputation management revisited: U.S. universities presenting themselves online', in T. Christensen, Å. Gornitzka and F.O. Ramirez (eds.) Universities as agencies reputation and professionalization Cham: Springer, pp. 67–91.

Gioia, D.A., Patvardhan, S.D., Hamilton, A.L. and Corley, K.G. (2013) Organizational identity formation and change. Academy of Management Annals 7(1): 123–193.

de Haan, H. (2014) Can internationalisation really lead to institutional competitive advantage? – a study of 16 Dutch public higher education institutions. European Journal of Higher Education 4(2): 135–152.

Hazelkorn, E. (2018) Reshaping the world order of HE: The role and impact of rankings on national and global systems. Policy Reviews in Higher Education 2(1): 4–31.

Hsieh, H.-F. and Shannon, S.E. (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–1288.

Hudzik, K.J. (2011) Comprehensive Internationalisation: From Concept to Action, Washington, D.C.: Association of International Educators.

Iosava, L. and Roxå, T. (2019) Internationalisation of universities: Local perspectives on a global phenomenon. Tertiary Education and Management 25: 225–238.

Johnstone, C. and Proctor, D. (2018) Aligning institutional and national contexts with internationalisation efforts. Innovative Higher Education 43: 5–16.

Kwiek, M. (2020) What large-scale publication and citation data tell us about international research collaboration in Europe: changing national patterns in global contexts, Studies in Higher Education. Epub. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1749254.

Kyvik, S. (2009) Geographical and institutional decentralisation, The Dynamics of Change in Higher Education, vol. 27, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 61–80.

Labianca, G., Fairbank, J.F., Thomas, J.B., Gioia, D.A. and Umphress, E.E. (2001) Emulation in academia: Balancing structure and identity. Organization Science 12(3): 312–330.

Luijten-Lub, A., van der Wende, M. and Huisman, J. (2005) On cooperation and competition: A comparative analysis of national policies for internationalisation of higher education in seven western European countries. Journal of Studies in International Education 9(2): 147–163.

March, J.G. and Olsen, J.P. (2006) 'Elaborating the “New Institutionalism”', in R.A.W. Rhodes, S.A. Binder and B. Rockman (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Political InstitutionsOxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–20.

Marginson, S. and van der Wende, M. (2007) ‘Globalisation and higher education’, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 8, OECD Publishing.

Neave, G. (ed.) (2000) The Universities’ Responsibilities to Society: International Perspectives, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science.

Nokkala, T. and Bladh, A. (2014) Institutional autonomy and academic freedom in the Nordic context - Similarities and differences. Higher Education Policy 27(1): 1–21.

Pinheiro, R., Geschwind, L. and Aarrevaara, T. (2014) Nested tensions and interwoven dilemmas in HE: The view from the Nordic countries. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 7: 233–250.

Prop. 2020/21:60. Forskning, frihet, framtid – Forskning och innovation för Sverige, Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

Puaca, G. (2020) Academic leadership and governance of professional autonomy in Swedish higher education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2020.1755359

Scott, W.R. (2013) Institutions and Organizations. Ideas, Interests, and Identities, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Segerholm, C., Hult, A., Lindgren, L. and Rönnberg, L. (eds.) (2019) The governing- evaluation-knowledge nexus. Swedish Higher Education as a case, Dortrecht: Springer.

SFS 1992:1434. Högskolelag, Stockholm: Riksdagen.

Shattock, M. (ed.) (2014) International Trends in University Governance: Autonomy, Self-government and the Distribution of Authority, London: Routledge.

Silander, C. and Haake, U. (2017) Gold-diggers, supporters and inclusive profilers: Strategies for profiling research in Swedish HE. Studies in Higher Education 42(11): 2009–2025.

SOU 2018:3. En Strategisk Agenda för Internationalisering, Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

SOU 2018:78. Ökad attraktionskraft för kunskapsnationen Sverige, Stockholm: Norstedts Juridik.

Stensaker, B. (2007) The relationship between branding and organisational change. Higher Education Management and Policy 19(1): 1–17.

Stensaker, B., Frølich, N. and Aamodt, P.O. (2020) Policy, perceptions, and practice: A study of educational leadership and their balancing of expectations and interests at micro-level. Higher Education Policy 33: 735–752.

Tange, H. and Jæger, K. (2021) From Bologna to welfare nationalism: International higher education in Denmark, 2000–2020. Language and Intercultural Communication 21(2): 223–236.

Teichler, U. (2015) Diversity and diversification in higher education: Trends, challenges and policies. Educational Studies, Higher School of Economics 1: 14–38.

Thoenig, J.C. and Paradeise, C. (2016) Strategic capacity and organisational capabilities: A challenge for Universities. Minerva 54(3): 293–324.

Yin, K.R. (2018) Case Study Research and Applications Design and Methods, 6th edn, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alexiadou, N., Rönnberg, L. Reading the Internationalisation Imperative in Higher Education Institutions: External Contexts and Internal Positionings. High Educ Policy 36, 351–369 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-021-00260-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-021-00260-y