Abstract

It is well-established that value framing can be a powerful rhetorical tool for politicians to influence voters’ expectations of policies and muster support. The effects that such policy framing may have on people’s reactions to subsequent policy information, however, remain largely unexplored. This paper addresses this question by investigating whether value framing of policy proposals can influence the aspects that people consider important when they receive (and evaluate) information regarding policy outcomes, as well as their satisfaction with them. A survey experiment (N = 2378) demonstrates that, when individuals have been exposed to information on outcomes, they sometimes consider the framed values more important than the actual policy measures. The experiment also indicates that value framing may sometimes influence satisfaction with the outcomes. However, these effects are in the positive rather than the hypothesized (negative) direction. Both effects primarily appear when the frames are charged with humanitarian values. Implications of the findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Today we are bombarded with messages that are framed in ways aimed at maximizing our expectations. Producers frame their products to increase their sales figures, employers frame decisions to enthuse their employees, and political parties present policies and promises to increase voter support. In politics, value words, such as freedom and fairness, have been described as particularly “powerful and reliable weapons in the persuader’s arsenal” (Nelson and Garst 2005, p. 490), and it is well known that politicians use such words when communicating their policies to voters (ibid; Domke et al. 1998). While research provides ample evidence that value framing can influence voters’ expectations of policies and muster support (e.g. Nelson et al. 1997; Schemer et al. 2012), how it may affect their responses to subsequent policy information is rarely theorized or empirically studied. This paper addresses this knowledge gap, focusing on (a) how frame-induced expectations of policies can affect what people consider important when evaluating information about the outcomes and (b) their satisfaction with said outcomes.

Research on democratic accountability shows that voters’ expectations on future policy measures can influence their evaluations of policy outcomes, and in particular that negative discrepancies can lead to negative retrospective evaluations (e.g. Naurin et al. 2019; Seyd 2016). For political parties interested in maintaining stable support from their voters, it should thus be of interest to understand how frame-induced expectations can affect subsequent performance evaluations, and how they can affect voter satisfaction, in particular. Moreover—regardless of consequences for voters’ satisfaction—when politicians provoke policy expectations using rhetoric, there are normative implications if these expectations extend beyond the policy content. According to mandate models of representation (e.g. Manin et al. 1999), voters’ policy preferences are connected to parties’ policy intentions via policy pledges, which makes shared beliefs about future policy actions and their outcomes crucial.

To investigate whether value framing affects how individuals evaluate subsequent policy information, a survey experiment was conducted in which participants were randomly shown different versions of a policy proposal followed by a report on ostensible outcomes. The experiment revealed some expected effects regarding considerations on the policy outcomes, but also some unanticipated (positive) effects regarding satisfaction. While the findings from this one-wave experiment can only provide information about immediate effects and not those that occur in more realistic settings in the longer term, it offers important contributions to existing research. First, the study contributes to the framing literature—which usually targets evaluations of the original policy message (Lecheler and de Vreese 2019)—by examining any unintended effects that this may have on people’s responses to subsequent policy information. As people will likely be exposed to additional policy information in real life, the assessment of such secondary framing effects should be of interest, both to framing researchers and to policymakers, and this study provides first steps in that direction. Second, the study contributes by delving into a different type of framing effect than those usually investigated—attitudes and considerations of competing values—by assessing whether the use of frames makes people assign a higher importance to values than to the actual policy measures. Third, beyond extending framing research to evaluations of secondary information, the study connects the framing literature to research on democratic accountability which examines the role of expectations in accountability processes (e.g. Markwat 2021a; Seyd 2016). This paper contributes to this literature by addressing not only whether expectations matter to performance evaluations, but whether it matters how these expectations were formed—something that is rarely addressed (Malhotra and Margalit 2014, p. 1000).

Finally, while policy results are primarily seen in long-term, situations, where short-term effects can also be decisive, are not uncommon. Between elections, governing parties often update policy decisions or formulate new ones in order to respond to changing events and demands (Narud and Esaiasson 2013). Welfare demands, for example, can change between elections and require the immediate reallocation of public resources. Likewise, unexpected situations can occur which demand urgent and invasive policy actions, such as a sudden economic downturn, the influx of refugees, or a contagious viral outbreak (e.g. Christensen and Lægreid 2020; Karremans and Lefkofridi 2020). If framing generates expectations beyond what is promised during such instances, it can have direct consequences for people’s behavior, from the likelihood of complying with economic measures to vaccinating against infectious diseases. The results from this study should thus be viewed in two ways. They should be seen as a first step in exploring the potential effects of framing beyond reactions to the original policy message—whose long-term persistence must be explored in the future—and as findings that may also be relevant in the short-term, when the timing between political decisions and their outcomes can be swift.

Value framing and expectations on policies

While scholars have yet to agree on a conclusive definition of framing, most studies define it as a message in which certain beliefs are activated and connected to a target object, making those beliefs appear particularly relevant (Lecheler and de Vreese 2019). Value framing, here, refers to a message that establishes an association between a certain value (e.g. freedom of speech) and an object. The current literature offers substantial evidence that this type of framing can influence people’s appreciation of policies for diverse issues such as abortion laws (Domke et al. 1998), immigration policies (Lecheler et al. 2015; Schemer et al. 2012), welfare policies (Shen and Hatfield-Edwards 2005; Slothuus 2008), gay rights policies (Brewer 2002, 2003), and school policies (Nelson and Garst 2005).

While value framing is expected to alter the perceived importance of potentially relevant considerations about a target object through changes in the applicability of certain values (Chong and Druckman 2007a; Nelson et al. 1997), its effects on attitudes to the object have been explained using an “expectancy value model” of opinion formation (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980). It is assumed here that social issues usually encompass multiple dimensions, which people may have different beliefs on. Each belief can be divided into two components; a “cognitive” component, which refers to the information that a person has about an object, and an “evaluative” component, which refers to the positive or negative valence that the person assigns this information (Petty and Cacioppo 1986). When people form their judgments, the model stipulates, they assign different weights to different dimensions, and their overall attitude becomes the weighted sum of their evaluative beliefs of the object on each dimension (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980).

The set of evaluative beliefs that affect an individual’s attitudes has been called a “frame in thought” (Chong and Druckman 2007a). By activating selected beliefs that people have stored in their long-term memory and connecting them to a target object, framing can affect these frames in thought, making the activated beliefs seem particularly relevant to consider when making a judgment of the object (e.g., Chong and Druckman 2007a; Nelson et al. 1997). If the activated beliefs have a positive valence, exposure to the frame will increase the importance of positive considerations (relative to other, potentially less positive ones) for people’s overall judgment, leading to a relatively higher appreciation of the same. Consider, for example, a proposal to introduce surveillance cameras in public places. Let’s say that “public safety” and “individual integrity” are two values that can be seen as potentially relevant dimensions of surveillance cameras, and that the public finds both of these values desirable. Say also that surveillance cameras can be seen as positive for public safety, but negative for individual integrity. If proponents of the surveillance cameras connect them to public safety, this “public safety” frame should, if successful, make people perceive their (positive) beliefs about the public safety aspects of the cameras as particularly important when they form their judgments about the cameras. This, in turn, would lead the recipients to appreciate the cameras more than they would have, had they not been exposed to this frame.

When it comes to the political domain, empirical studies have largely supported the expectancy value model. They have shown that frames, by making considerations about widely held values appear more important than other potentially relevant considerations when people evaluate policies, can increase their overall appreciation of these policies (Lecheler and de Vreese 2019). Based on this evidence, the following hypothesis is stipulated:

H1a

By framing their policies with widely held values, policymakers can increase voters’ appreciation of the same.

While positive effects on voters’ appreciation of policies are predicted on the aggregate level when these are framed with widely held values, it is important to keep in mind that frames work by altering the perceived relevance of those values, not the valence people assign to the same (whether they consider the values to be positive or negative; Petty and Cacioppo 1986). If a recipient does not consider a framed value desirable, they may acknowledge that the value and a policy are connected but disregard it when forming their judgments (Baden and Lecheler 2012, p. 365) potentially appreciate the policy less. In fact, even when an individual shares a value and finds it positive, she may not assign weight to it when forming her attitudes. Existing studies convincingly argue that individuals organize values hierarchically and prioritize different values (e.g. Nelson et al. 1997) when they make political judgments. Since those priorities are often based on positioning on ideological dimensions (Jost et al. 2009; Thorisdottir et al. 2007), frames that emphasize widely held values may still render more pronounced effects among those whose ideological predispositions align with the values—something which previous studies have supported (e.g. Brewer 2002; Nelson and Garst 2005; Schemer et al. 2012; Shen and Hatfield-Edwards 2005). This paper thus poses a second, moderating hypothesis:

H1b

The effects of value framing on appreciation of policies will be stronger among individuals whose ideological predispositions align with the framed values.

Having predicted the effects of framing on people’s initial policy evaluations—which essentially replicates previous research—this paper offers predictions regarding which “secondary” effects framing might have on people’s evaluations of the policy outcomes.

Framing, policy expectations, and evaluations of policy outcomes

Research on democratic accountability shows that expectations on policy measures can affect voters’ satisfaction with subsequent results. The predominant model for predicting such effects, the “expectancy (dis)confirmation model,” suggests that evaluations of outcomes are shaped by people’s perceptions of these outcomes, adjusted for their initial expectations (Markwat 2021a; Seyd 2016). This model corresponds with the mandate model of democratic representation (e.g. Manin et al. 1999), according to which voters hold governments accountable by comparing their predictions of parties’ policy intentions with the government’s policy performance (ibid, p. 29). Expectations, here, serve as a standard against which policy performance is compared, with perceived discrepancy (or concordance) between the two shaping voters’ evaluations. When government performance matches expectations, they should have little effect on evaluations, as the government will be perceived as having done what it should. When performance surpasses expectations, there will be a positive discrepancy inducing positive evaluations, and, finally, when performance fails to live up to expectations, this will yield a negative discrepancy, thereby triggering negative evaluations.

While some important exceptions should be noted,Footnote 1 most studies find support for the expectation (dis)confirmation model, and, in particular, that negative discrepancies can produce negative evaluations. Policy outcomes that fail to live up to voters’ expectations can lead to political disappointment (Seyd 2016), negative evaluations of public services (Morgeson 2013), and the government’s performance (Naurin et al. 2019; Waterman et al. 1999), and reduced voter support (Malhotra and Margalit 2014). If framing can influence voters’ expectations of policies and increase their appreciation of the same (H1a), while higher appreciation increases the likelihood of people becoming disappointed with the subsequent results, the following hypothesis can be stipulated:

H2a

By increasing appreciation of policy proposals, value framing will, indirectly, increase the likelihood of voters experiencing disappointment when they receive information on the policy outcomes.

Although few studies have explored the conditional effects of ideological predispositions on the relationship between expectations and satisfaction, there is some existing evidence indicating connections between ideology and values. Specifically, Seyd (2016, pp. 338–339) found that individuals whose ideological predispositions and values aligned with the governing party’s (individuals with leftist values, and a Labor party in government) were more likely to experience a negative discrepancy between expectations and outcomes, and to express disappointment, than were individuals with the opposite (right) positioning. Based on these findings, and the fact that framing research has repeatedly shown that ideological predispositions can moderate value framing effects, H2a should be refined, similarly to H1a. Specifically, it is hypothesized that:

H2b

The indirect (negative) effects of value framing on satisfaction through changes in appreciation of policy proposals will be stronger among individuals whose ideological predispositions align with the framed values.

While the expectation (dis)confirmation model has dominated research on expectations and retrospective evaluations in politics, when predicting framing effects on such subsequent evaluations, the expectancy value model (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980) should also be taken into account. In particular, it is important to consider how the framing of a policy proposal may influence the relative importance that people assign different considerations about the policy measures when evaluating subsequent outcomes.

In order for frame-induced expectations to matter when people evaluate subsequent information, the initial frames must have produced some cognitive changes in people’s perceptions of which aspects of an object are important to consider (Baden and Lecheler 2012). If frames have produced such cognitive changes, then the considerations relayed by the original frame should form the “knowledge environment” wherein subsequent information is processed (Ibid, p. 374). Assuming that this is the case, two outcomes can be anticipated for subsequent judgments. First, since frames are presumed to increase the relative importance of considerations emphasized by the frame, we can expect the recipients to perceive considerations regarding the framed values as more important when evaluating the policy outcomes than they would have, had they not been exposed to the frame (Chong and Druckman 2007a; Nelson et al. 1997). Second, given that frames affect people’s overall assessment of an object by changing (or reorganizing) the relative weights of all potential considerations they may have about it (ibid), we can expect people to also assign considerations regarding other (less emphasized) aspects—including the specific policy content—relatively less weight when evaluating the outcomes. Consider again the example with surveillance cameras discussed above. If a frame increases the weight of certain (value-related) considerations—such as “public safety”—when people make their summary assessments of the policy outcomes, the relative weight of other potential considerations—including the installation of the cameras per se—should decrease. Hence, it is hypothesized that:

H3a

Individuals exposed to value framing of policy proposals will perceive considerations about those values as relatively more important (1) and considerations about the specific policy measures as relatively less important (2) when they evaluate information on the policy outcomes.

Given that value framing is likely to be more effective on individuals with corresponding ideological predispositions (e.g. Schemer et al. 2012), and that those individuals are more likely to use frame-related considerations when asked to make their judgments (e.g. Brewer 2002; Nelson et al. 1997), the effects are, again, refined to account for ideological predispositions:

H3b

The effects of value framing on the perceived importance of value-related considerations will be stronger among individuals whose ideological predispositions align with the framed values.

Finally, this paper predicts that value framing can reduce satisfaction with policy outcomes—not only by increasing the appreciation of the policy proposals (H2a)—but also by influencing the perceived importance of value-related considerations. To reiterate, traditional theory of democratic accountability stipulates that voters evaluate political results by comparing what they expected policies to attain before an election with what they attained after the election (e.g. Manin et al. 1999). Given that voters make such comparisons, and that value framing causes people to perceive considerations related to values—which are usually difficult to live up to (Giddens 1998)—particularly important when evaluating the policies (H3a), mismatches between what voters expect the policies to deliver substantively and what they deliver should be more likely. Together with studies that show that such mismatches can reduce voter satisfaction (Seyd 2016), it is assumed that value framing, by increasing the perceived importance of value-related considerations when assessing the outcomes, can indirectly increase their disappointment with the same:

H4a

By increasing the perceived importance of value-related considerations when evaluating information about policy outcomes, value framing will indirectly increase the likelihood of voters experiencing disappointment with said outcomes.

Finally, we can expect that the indirect effects that framing has on satisfaction, via its effects on the perceived importance of value-related considerations, will be moderated by ideological predispositions. Not only should individuals whose ideological predispositions do not align with the framed values be less likely to accept, store, and retrieve frame-related considerations when asked to make their judgments (e.g. Brewer 2002), they may simply not become disappointed if outcomes fail to live up to those values. Specifically, even if a frame has led an individual to perceive a value as an important aspect of a policy, if she does not strongly endorse or prioritize this value, she may disregard considerations of the same when making her assessments (Baden and Lecheler 2012), potentially becoming (more) content if the policy fails to deliver in this regard. Hence:

H4b

The indirect (negative) effects of value framing on satisfaction, through changes in the perceived importance of value-related considerations, will be weaker among individuals whose ideological predispositions do not align with the framed values.

Before proceeding to the empirical tests, some notes on limitations are in order. First, since the hypotheses rest on an assumption that the initial framing effects are in place when people evaluate subsequent information, the durability of framing effects should be discussed. At the individual level, prior and added knowledge have been identified as factors that may condition effect-durability. Scholars have argued that for frames to have a lasting effect on people’s cognitive states, they must have sufficient knowledge to understand a connection between the target object and the emphasized values, while still having sparse-enough knowledge to allow for significant changes (Baden and Lecheler 2012, p. 375). Hence, people with moderate levels of knowledge should be more likely to experience persistent framing effects than individuals with low or high knowledge (Brewer 2003; Lecheler and de Vreese 2011; Slothuus 2008). Another factor that may have an effect is the cognitive style with which frames are processed. Here, processing that favors the formation of confident beliefs, such as cognitively demanding and “online” processing, seems more likely to generate persistent effects than less cognitively demanding or memory-based processing (Chong and Druckman 2010, 2013). Furthermore, contextual factors, such as repeated exposure and prevalence over competing frames, may contribute to effect maintenance (Chong and Druckman 2007b, 2010, 2013; Lecheler and de Vreese 2013), as may frames that generate strong initial attitudes (Chong and Druckman 2013), and address widely available considerations and values (Brewer 2003; Chong and Druckman 2007b; Nelson et al. 1997).

Besides limitations in the persistence of framing effects, we should also take into consideration the fact that the expectation-based models target only selected mechanisms involved in the complex process when people evaluate outcomes. For example, there is a difference between not attaining an end goal and not generating change in the promised direction. People who are dissatisfied with the status quo may be content with any step in the right direction (Shanks and Miller 1990). Voters are also likely aware that governments often must compromise with other parties, which can make it practically difficult to fully attain what they have promised (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2005). Some may thus acknowledge the failure of specific policy measures but still appreciate value-driven attempts at policymaking (Burlacu et al. 2018) and reward parties for implementing policies that are in line with their personal preferences (Markwat 2021b). Furthermore, since people tend to be “dissonance-averse,” some may counterargue or reject information that could cause such dissonance between expectations and outcomes (Tavris and Aronson 2008), and other factors, such as identification with the incumbent party (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2005) and personal experience with the outcomes are likely to impact evaluations, as well. Since the expectancy value model is frequently referenced to explain framing effects on initial policy evaluations, it should be of value to explore whether the effects extend to evaluations of subsequent policy-relevant information. When discussing this study’s implications, it is however crucial to acknowledge the fact that other mechanisms are likely also involved.

Experimental study

The policy case: Swedish labor migration

The hypotheses are tested through a survey experiment with Swedish citizens, with labor migration functioning as the policy case. While in the past, Sweden’s labor migration policies have been quite restrictive, the past few decades have seen parties on both sides of the ideological left–right divide advocating for and taking concrete steps in a more liberal direction. The established Swedish parties have largely agreed on the liberalization measures, but the specific arguments have been more divided (e.g. Berg and Spehar 2013). The main differences come down to whether policies are motivated by humanitarian values (left/green parties) or by economic values (right parties) (ibid). In a government bill, for example, the four-party right-wing coalition government “the Alliance” referred to an EU directive, stating that “the intention is to make the Union more attractive to […] workers from around the world and promote its competitiveness and economic prosperity” (2013, p. 151, emphasis added by author). In the following year, the Left Party asserted that “Fair conditions for labor immigrants. […] the exploitation of foreign labor […] must stop” (2014, p. 3, emphasis added by author), and the Greens said that “we want to strengthen labor migrants’ rights and ensure that people are not exploited” (2014, p. 19, emphasis added by author). While the parties differ in terms of their rhetoric on labor migration, they also agree on certain values. Examples include well-functioning integration (the Alliance 2014, p. 53; the Greens 2014, p. 9), and opportunities for individuals and the society (Liberals 2014, p. 4; Left Party 2009, p. 2). Thus, labor migration policies in Sweden constitute a good case for testing the hypotheses of this paper, because (1) the effects of different types of value framing—framing that is charged with left- and right ideological, and “universal” left–right neutral values—can be tested, and (2) it is possible to assess whether the effects are conditioned on individuals’ ideological predispositions while keeping the treatments realistic in terms of the contemporary political discourse.

Method, sample, and design

The hypotheses were tested using a one-wave survey experiment with 2378 self-recruited members from a larger online panel of Swedish citizens, maintained by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg. The survey was fielded between December 2015 and January 2016. The sample was relatively diverse; however, it had certain biases in terms of politically interested and highly educated individuals (for demographic breakdowns, see supplemental file S:1) which are factors that may correlate with political knowledge (Highton 2009). Since knowledge may condition framing effects in both the short and long term (Baden and Lecheler 2012), these biases should be noted when discussing the study’s general implications. Because framing effects may be most pronounced among moderately knowledgeable individuals (Lecheler and de Vreese 2011; Slothuus 2008), it is important to consider that other, more diverse samples, may render more notable effects than this sample.

Randomization checks on demographics showed that the treatment groups were balanced regarding political interest and trust, sex, age, and left–right orientation (see supplemental file S:2). However, there was a slight imbalance in the level of education, and personal connection to migrant worker(s)—both relevant factors that could influence the levels of knowledge of the policy issue (labor migration). Hence, these have been controlled for in the analyses.

The experiment had a sequential design. Participants were first presented with a fictitious policy proposal about labor migration with corresponding questions (sequence 1). After having responded to the questions, they were shown an intervention with information on the policy outcomes, again with corresponding questions (sequence 2).

Treatments

The treatments were presented in the form of a flyer sent from a fictional party. Two policies to make the Swedish labor migration laws more liberal were outlined, (1) to extend the time that migrant workers have at their disposal to find a new job once their employment contract is canceled, and (2) to make employment contracts for migrant workers legally binding. Respondents were randomly assigned one of four versions of the treatments, which varied in type, and presence, of value-laden words.

The control version was formulated in neutral terms with value words omitted. The other versions were tailored to fit the context and resemble different types of values from the Swedish labor migration debate. The first treatment, the “humanitarian frame,” included values emphasized by left/green parties that corresponded with traditional left-leaning values (Fuchs and Klingemann 1990): “equality,” “fairness,” “solidarity,” “safety,” and “no exploitation.” The second version, the “economic frame,” included right-leaning market-oriented values (Thorisdottir et al. 2007) emphasized by Swedish right-leaning parties in the labor migration debate: “competitiveness,” “prosperity,” “attractive,” “competence,” “and “effectiveness.” The third treatment, the “integration frame,” included words such as “well-functioning integration,” “opportunities,” “future,” and “development,” which have a positive connotation in the Swedish labor migration debate across left–right divides and thus can be seen as left–right ideology-neutral values in this context. English translations of the treatments are presented in a supplemental file (S:3).

As a validity check, respondents were asked how realistic they found the policies to be. An ANOVA confirmed that respondents considered the policies to be fairly realistic; on a scale of 1 (Not realistic at all) to 7 (Very realistic), policies were rated close to the midpoint of 4 (MControl = 3.69; MHumanitarian = 3.77; MIntegration = 3.78; MEconomic = 3.63; F3,2191 = 1.18, P = 0.317). Respondents were also asked to rate the policies on an ideological scale ranging from 1 (Far to the left) to 7 (Far to the right). All treatment groups placed the policies somewhat to the right of the midpoint of 4 (MControl = 4.34; MHumanitarian = 4.10; MIntegration = 4.42; MEconomic = 4.45; F3,2324 = 7.69, P = 0.000). Hence, while similar policies have been proposed by parties on both the left and right in Sweden, liberal labor migration positions may still be perceived by Swedes to be somewhat right-leaning. Regardless the reason, what matters most is whether the frames influenced the respondents’ perceptions of the policies in the expected (left–right) directions. As anticipated, respondents who were exposed to the humanitarian frame placed the policies further to the left than the control group did (P = 0.012). Respondents exposed to the economic frame also placed the policies in the expected (right) direction relative to the control group, however, in this case, the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.560). This should be considered when conditional effects of respondents’ ideological predispositions are discussed. As expected, the group exposed to the integration frame did not differ in left–right placement relative to the control group (P = 0.782).

Intervention

Once the participants answered questions about the policy proposal, they were presented with a fictional news article that reported on policy outcomes. They were asked to imagine that three years had passed and that the pledge-making party was in office. All participants were given the same intervention.

To test the hypothesis that frames can create a discrepancy between voters’ policy expectations and subsequent outcomes by emphasizing abstract values, two criteria had to be met. First, expectations related to the specific policy content had to be confirmed; hence, respondents were informed that the government had (1) extended the time for migrant workers to find new jobs, and (2) made employment contracts for migrant workers legally binding. Second, it was important to fail to meet the expectations related to the framed values. This was achieved by including comments from experts bringing up negative aspects of the current situation for migrant workers, which related to values emphasized in the treatments without being direct outcomes of the policies. To avoid reminding respondents of the exact treatment wordings, the critique used similar terms while omitting the exact value words.

Unfulfilled expectations related to the humanitarian frame were conveyed by including comments from a labor attorney, saying that “many still work under poor conditions with low wages and long working hours.” Unmet expectations related to the economic frame were conveyed in comments made by a CEO who said that “under current conditions, we cannot expect more people to seek jobs in Sweden,” and by the labor attorney, who stated that the policies had “not made the conditions for migrant workers more appealing.” Finally, the expectations related to the integration frame were expressed by the labor attorney who said that “the government’s efforts to improve migrant workers’ chances of establishing themselves in the labor market are insufficient […] as this also requires a good understanding of the Swedish language, society, and laws.” The intervention concluded with a comment from a representative of the incumbent party, who commended the government for its implementation of the policies but cautioned that the effects of those measures can take time. For an English translation of the intervention, see the supplemental file (S:4).

Measurements

Appreciation of the policy proposal was measured by an index of two questions asked after exposure to the treatment but before the intervention: “How do you like the policy proposals about labor migration?” (7-point scale from 1 “Strongly dislike” to 7 “Strongly like”), and “How satisfied do you feel with the measures the Party pledges to take concerning labor migration?” (7-point scale from 1 “Very dissatisfied” to 7 “Very satisfied”). The index was normalized to range from 0 “Low appreciation” to 1 “High appreciation” (Cronbachs’ α = 0.92, M = 0.53, SD = 0.24).

To determine the importance assigned different considerations about the policy outcomes, respondents were, following the intervention, asked to rate the degree to which the policy pledge had been fulfilled, with a follow-up question: “What was important to you when you evaluated the degree to which the Party has fulfilled its pledges on labor migration?”. The follow-up question was closed-ended with eight items describing the situation for migrant workers. Six items related to the treatments (two items/treatment) and two items presented outcomes on the exact policies. The items, presented in randomized order, were: “Longer time for migrant workers to find a new job” and “Legally binding employment contracts” (specific policies), “Increased equality and less exploitation” and “Safe and fair working conditions” (humanitarian frame), “Well-functioning integration” and “Clear and concrete working conditions” (integration frame), “Increased competitiveness and competence” and “Attractive and favorable working conditions” (economic frame). For each item, respondents answered on a 7-point scale with designated endpoints of 1 “Not important at all” and 7 “Very important,” and a designated midpoint of 4 “Neither important nor unimportant.”

Satisfaction with policy outcomes was measured by the question: “In sum, how satisfied do you feel with the outcomes of the labor migration policies?” Respondents answered on a 7-point scale with designated endpoints of 1 “Very dissatisfied” and 7 “Very satisfied,” and a designated midpoint of 4 “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied” (M = 3.35, SD = 1.32).

To gauge conditional effects of value predispositions, finally, a traditional left–right measure was used. Specifically, prior to being exposed to the treatments, respondents were asked: “Political parties are sometimes placed on a political left–right scale. Where would you place yourself on such a scale?” Respondents answered on an 11-point scale with designated endpoints of 0 “Far to the left” and 10 “Far to the right,” and a designated midpoint of 5 “Neither to the left nor the right” (M = 4.78, SD = 2.44). Although positions on a left–right scale can be a rather simplistic measure of value predispositions and people may hold more pluralistic views, this ideological dimension is known to capture a wide range of political values in western democracies, including those used in this experiment (Fuchs and Klingemann 1990; Thorisdottir et al. 2007). It has proven to be theoretically useful and to offer empirically valid information in an efficient manner (Jost et al. 2009, p. 312).

Two covariates were included for control in all analyses, level of education and connection to labor migrant(s), as some treatment groups were unbalanced on these variables. Prior to analyses, all continuous variables were normalized to range from 0–1, and were mean-centered.

Analytic strategies

To investigate whether the frames influenced respondents’ appreciation of the original policy proposals (H1), and the weight they assigned different considerations after exposure to the policy outcomes (H3), appreciation of the proposals, as well as each item depicting different aspects of the policy outcomes were regressed on each treatment group against the control group. The level of satisfaction with policy outcomes was also regressed on the treatments, to assess the frames’ total effect on satisfaction. To determine whether the frames had indirect effects on the respondents’ level of satisfaction with the policy outcomes via initial appreciation of the proposals (H2), and the weight they assigned different considerations on the outcomes (H4), a method proposed by Hayes (2013) was applied. This method, which is common in contemporary studies of indirect framing effects (e.g. Lecheler et al. 2015), employs bootstrapping (or resampling) to generate empirically derived confidence intervals for the indirect effect, thereby relaxing the normal distribution assumption. To assess the moderating effects of ideological predispositions, respondents’ left–right predispositions were included in all regression models. The SPSS macro PROCESS (model 59) created by Hayes (2013) was used for all estimates.

Methodological limitations

To assess indirect framing effects on satisfaction with policy outcomes through policy expectations (H2 and H4), it was necessary to measure levels of satisfaction and expectations following exposure to the treatments. This type of “post-treatment” design for studying indirect effects comes with some limitations. First, directional causality can only be established between the treatments (value framing) and the mediators (policy appreciation and importance of considerations), and between the treatments and the outcome variable (satisfaction), respectively, not between the mediators and the outcome variable, themselves (Imai et al. 2011). Hence, reversed causality between expectations and satisfaction cannot be ruled out. Second, because the indirect effects of the frames on satisfaction are conditioned on appreciation and considerations (mediators), which are measured post-treatment and thus not randomized, omitted variable biases cannot be ruled out for those effects. As would be the case with a cross-sectional study, therefore, inferences about the causal indirect effects of value framing on satisfaction must be made with a degree of caution.

Results

Value framing and appreciation of policy proposals

The first hypotheses stipulate that value framing can increase voters’ appreciation of policy proposals (H1a), particularly among individuals whose ideological predispositions align with the framed values (H1b). Results from OLS regression analyses (Table 1) reveal a main effect of the humanitarian frame on appreciation. Respondents exposed to this frame expressed greater appreciation of the policies than the control group did, however, there was no interaction with ideological predispositions. The results for the other two frames revealed no main effects, but significant interactions between exposure to the frames and ideological predispositions. In both cases, the interaction terms indicated that the association between framing and appreciation becomes more positive with an ideological right orientation.

Because the analyses revealed interactions between the integration- and the economic frames and ideological predispositions, conditional effects of those frames were estimated for individuals with different positions on the left–right scale (at the mean and ± 1 SD from the mean). The results showed that the integration frame had a positive effect on appreciation of the policies among individuals leaning to the right (B = 0.049, SE = 0.020, P = 0.017), but not among individuals around the center (B = 0.024, SE = 0.015, P = 0.116) or to the left (B = − 0.014, SE = 0.023, P = 0.539). The economic frame also had conditional effects on appreciation, but only among individuals to the left and, for those individuals, the effects were negative (B = − 0.057, SE = 0.023, P = 0.011). No effects were found for individuals around the center (B = − 0.002, SE = 0.015, P = 0.890) or to the right (B = 0.035, SE = 0.021, P = 0.091).

In sum, the humanitarian frame rendered a positive effect on appreciation (H1a supported) which was not conditional on ideological predispositions (H1b not supported). The integration frame did not increase appreciation generally (H1a not supported), but conditionally among individuals to the right (H1b supported). The economic (rightist) frame yielded no results in the hypothesized directions. Perhaps this frame has been more salient in the Swedish debate and made economic considerations chronically accessible to respondents. The lack of effects on right-leaning individuals may then be due to this frame being “redundant” among the participants (Baden and Lecheler 2012), while the negative effects on left-leaning respondents could be due to right-of-center partisan cues rather than a negative attitude to the economic values, per se (e.g. Armstrong and Wronski 2019). While previous research indicates that partisan cues can moderate framing effects, however, they do not seem to eradicate them—not even among strong partisans (Nelson and Garst 2005; Slothuus 2010)—which may make the latter as a single explanation less probable. Regardless, the results on the economic frame fail to confirm both H1a and H1b, and the hypotheses are thus rejected in this case.

Value framing and evaluations of information on policy outcomes

The remaining hypotheses target the effects that value framing of policy proposals has on how people evaluate policy outcomes. H3a stipulates that value framing will increase the weight voters assign considerations that relate to the values, while simultaneously decreasing the weight they assign the specific policy content when they evaluate the outcomes. The hypotheses were tested by regressing each “consideration” item on each treatment group against the control group, including left–right predispositions as an interaction variable (H3b). The results are presented in Table 2.

The analyses yielded effects of the humanitarian frame on respondents’ considerations about the outcomes. In line with H3a, respondents exposed to this frame assigned more weight than the control group to considerations related to the humanitarian values, “Increased equality and less exploitation” and “Safe and fair working conditions.” Those in this group also assigned less weight to the exact policy to “Extend the time for migrant workers to find a new job.” However, the analyses also revealed an unanticipated effect. Compared to the control group, respondents in the humanitarian treatment group assigned more weight to the other policy measure, to “Make employment contracts for migrant workers legally binding.” In this case, the frame seems to have increased the focus on the specific policy content rather than decreased it. It is possible that “legally binding contracts” conformed with respondents’ interpretations of the humanitarian values, such as “safe” and “fair,” and that this resulted in the policy becoming more salient. Regardless, this result does not align with H3a. The analyses yielded no interactions between exposure to the humanitarian frame and ideological predispositions (H3b not supported).

The “integration” frame had no main effects on respondents’ considerations. In this case, however, exposure to the frame interacted with ideological predispositions for both items targeting values emphasized by the frame: “Well-functioning integration” and “Clear and concrete working conditions,” as well as for one associated with the economic frame, “Increased competitiveness and competence.” Analyses of the conditional effects of ideological left–right predispositions (at the mean and ± 1 SD from the mean) revealed that respondents on the right tended to assign more weight to “Well-functioning integration” (B = 0.064, SE = 0.024, P = 0.008) and “Increased competitiveness and competence” (B = 0.042, SE = 0.022, P = 0.049), while there was no effect on individuals close to the center and to the left. The analyses revealed no conditional effects on the weight assigned to “Clear and concrete working conditions” at the conventional 95% confidence level (positive effects were seen among right-leaning respondents at a lower, 90% confidence level, B = 0.041, SE = 0.021, P = 0.052). Finally, the analyses of the economic frame did not reveal any effects on respondents’ considerations, neither general nor conditional ones.

The remaining hypotheses stipulate that value framing of policy proposals can indirectly decrease satisfaction with policy outcomes, by raising appreciation of the policies (H2) and by increasing the relative weight assigned to considerations related to the framed values (H4). Such indirect effects entail two things: a significant relationship between the frames and the mediating variables (appreciation of policies and weight assigned to value-related considerations), as well as between the mediators and the dependent variable (satisfaction). The first condition was partly supported. The humanitarian frame influenced both appreciation of the policies (Table 1) and the weight respondents assigned value-related considerations about the policy outcomes (Table 2). The integration frame showed some effects in the expected direction on both mediators (fully conditional on ideological predispositions), and the economic frame had conditional effects, but only on appreciation of the policies. Table 3 presents results regarding the second condition, the relationship between mediators and satisfaction, as well as the effect of each treatment on satisfaction when mediators are omitted (see “Model 1” for each treatment).

The humanitarian frame had positive effects on satisfaction, but there were no effects of the other two treatments (neither on average nor in interaction with ideological predispositions). Since, however, indirect effects can exist without a bivariate relationship between treatment and the outcome variable,Footnote 2 further probing was done on all treatment groups.

The relationship between proposed mediators and satisfaction with policy outcomes was explored in three multivariate OLS regression analyses (one for each treatment group against the control group), with satisfaction as the dependent variable, all proposed mediators as independent variables, and left–right predispositions as a moderator (see “Model 2” in Table 3 for each treatment). All analyses revealed positive associations between the first mediator (appreciation of policies) and satisfaction, indicating that higher appreciation of the policy proposals generates higher satisfaction with the policy outcomes. Since all treatments had some effect on appreciation (either in general or conditional on ideological predispositions), the results suggest that value framing, by influencing appreciation of policy proposals, may also indirectly impact satisfaction with resulting outcomes. Regarding the second proposed mediator (weight assigned to different considerations), the analyses yielded no associations with satisfaction; hence, there are no indications of indirect framing effects via changes in considerations.

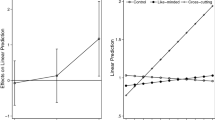

The relationship between treatments, proposed mediators, and satisfaction with policy outcomes are illustrated in Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Paths on the left-hand side depict treatment effects on appreciation of the policy proposals and the weight assigned different considerations about policy outcomes (mediators). Paths on the right-hand side depict the relationship between mediators and satisfaction with the policy outcomes. The path from treatment to satisfaction depicts the direct effects of the frames when accounting for indirect effects. Paths deriving from “left–right predispositions” (designated with an i) depict interaction terms. To facilitate reading, the figures only include those mediators that should be causally influenced by the respective treatment, according to the hypotheses. Coefficients are included in the figures when significant, with paths highlighted.

To assess the statistical significance of the indirect framing effects on satisfaction via appreciation, 95% bootstrapped confidence intervals were produced for the indirect effect of each treatment (effects can be considered significant when confidence intervals do not cross zero; Hayes 2013). To account for the conditional effects of ideological predispositions (H2b), the effects were estimated for individuals at the mean and ± 1 SD from the mean on the left–right scale. The results are presented in Table 4.

The results in Table 4 largely confirm the patterns depicted in Figs. 1–3. By influencing appreciation of the initial policy proposals, the humanitarian- and integration frames had positive indirect effects on policy outcome satisfaction. In both cases, the effects were conditional on ideological predispositions. Indirect effects of the humanitarian frame were seen among individuals placing themselves close to the center on the left–right spectrum, whereas indirect effects of the integration frame were seen among individuals on the right. The economic frame also had an indirect effect on satisfaction but, in this case, the effect was negative and seen among individuals on the left. Finally, and outside the scope of the hypotheses, the analyses revealed a positive direct effect of the humanitarian frame on satisfaction when indirect effects were accounted for (Table 4). Collectively, and contrary to the hypotheses, the results imply that value framing of policy proposals does not entail an indirect lower satisfaction with outcomes, either by influencing respondents’ initial appreciation of the policies (H2 rejected) or by influencing the weight they assign the emphasized values when evaluating the outcomes (H4 rejected).

Concluding discussion

This paper has explored how value framing of policy proposals affects voters’ evaluations of subsequent policy-relevant information. It offers several key takeaways. First, it shows that value framing can sometimes affect the importance people assign to different considerations when evaluating policy outcomes, and that values can be considered more important than the actual policy content. These effects were mainly seen for one of three frames, which targeted left-leaning (humanitarian) values, and not at all for another, right-leaning “economic” frame. A first takeaway is thus that effects on considerations, which are common in “typical” framing studies that focus on evaluations of the original policy message (Lecheler and de Vreese 2019), may be less evident when evaluations are made on subsequent information. One explanation for this could be that voters are aware that it can be difficult for governments to achieve everything that has been promised (Jenkins-Smith et al. 2005), especially when it comes to abstract values (Giddens 1998), and therefore focus less on such values when evaluating policy outcomes. Another possibility is that the effects of values depend on the accessibility of the frames. If Sweden had experienced widespread economic rhetoric in terms of labor migration, for example, then respondents might already hold firm and accessible beliefs about the economy and liberal labor migration, making the economic frame less effective (Baden and Lecheler 2012). Similarly, if the leftist rhetoric about humanitarian values was less widespread or accessible, then that frame would have a greater opportunity to create new applicability links and thus also generate more notable effects on respondents. These scenarios lie outside the scope of this paper but could be explored in future research by replicating the study in other contexts and policy domains, or by including factors that could affect the availability of frames, such as political knowledge—a variable which this study’s sample could have been positively-biased towards.

The second key takeaway concerns the indirect effects of value framing on satisfaction with policy outcomes. First, the analyses showed no effects of the weight that people assigned different considerations on satisfaction; neither when the considerations were affected by the initial framing (humanitarian and integration frame), nor when they were not (economic frame). Hence, what voters expect the policies to deliver substantively seems to have little effect on how satisfied they feel with what is attained. Second, while the analyses indicated some indirect framing effects on satisfaction via the other proposed mediator (appreciation of the original policy proposal), those effects were small and conditional on respondents’ left–right predispositions. More striking, they were in the opposite direction to what the hypotheses predicted. When appreciation of the policies was positively affected by the frames, satisfaction with the policy outcomes increased (not decreased). These results suggest that, rather than having a negative impact when voters are informed of the results, value framing may, if anything, have minor positive effects on satisfaction. While most previous studies on the role of expectations for retrospective policy evaluations do not align with these results, a few studies do, showing that higher expectations may sometimes entail only weak, or even slightly positive effects (Malhotra and Margalit 2014; Markwat 2021a). Maybe people are motivated to avoid the cognitive dissonance that results from being exposed to information that contradicts previous expectations, and therefore, regardless of how these expectations were formed, reject any information that would cause such dissonance (Tavris and Aronson 2008). Another possibility is that people are able to differentiate between outcomes that a government can reasonably be held accountable for (specific policy measures) and results that they are less likely to be able to control (abstract values), and thus reward politicians for being idealistic in their campaigns even when outcomes fail to live up to the ideal (Burlacu et al. 2018). The effectiveness of policies in delivering may, in other words, play a lesser role in voters’ evaluations than whether the policies are perceived as being motivated by the “right” reasons. Yet another possibility is that values outside of the frames matter more to evaluations of the outcomes. Individuals that dislike “multiculturalism,” for example—or dislike immigration per se—may become quite satisfied when they learn that policies have failed to make migration to Sweden more appealing. Pre-measures of participants’ issue-specific attitudes should be included in future research to investigate this possibility.

This paper is one of the first attempts to explore what effects value framing can have beyond people’s reactions to the original (framed) message. However, the findings should be viewed as indicative rather than conclusive. First, participants in the study were exposed to the policy outcomes in direct response to the policy proposal. In reality, many policies have outcomes that are only revealed in the long term, which can make it difficult to compare the policy outcomes to the original policy message. On the other hand, an increasing number of studies have suggested that while framing effects may attenuate over time for certain individuals, others may experience quite persistent effects, depending on a variety of individual and contextual factors (Lecheler and de Vreese 2011, 2013; Chong and Druckman 2007b, 2010). In the future, studies should be done with time lags included between the initial exposure to the policy frame and the exposure to subsequent information. This would allow us to determine whether the results hold in more realistic settings. Those studies should also include individual moderators that could influence the persistence of framing effects, such as processing mode and issue-relevant knowledge. Finally, since political parties can be expected to compete not only in framing policies but also in framing the outcomes, it would be interesting to follow up on this study by randomly exposing individuals to positive or negative information on the outcomes.

While it is important to acknowledge the limited external validity of this experiment, it does offer some initial steps towards investigating an important part of framing effects in political communication that has thus far been largely unexplored: people’s evaluations of additional policy-relevant information. For now, the study adds to our knowledge of framing effects by suggesting that when policy proposals are framed with abstract values, people may (1) focus more on those values than the actual policy content, and (2) they may do so not only when evaluating the original policy message, but also when evaluating additional information. Furthermore, the study speaks to a growing literature that addresses the role of expectations for voters’ retrospective policy evaluations (e.g. Malhotra and Margalit 2014; Markwat 2021a; Seyd 2016). The results suggest that, above and beyond what a policy was expected to attain substantively, voters’ initial appreciation of the policy proposal (be it influenced by framing or not) determines their satisfaction with its outcomes. Future research should follow up on this study to determine under which conditions value framing of policy proposals can, and cannot, influence voters’ evaluations of subsequent, policy-relevant information.

Data availability

Data used in the analyses can be obtained from the author upon request.

Notes

Treatment effects can, for example, exist only indirectly through a mediator, or there may be several opposing indirect and/or direct effects that cancel each other out (MacKinnon et al. 2000).

References

Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 1980. Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Armstrong, G., and J. Wronski. 2019. Framing hate: Moral foundations, party cues, and (in)tolerance of offensive speech. Journal of Social and Political Psychology 7 (2): 695–725.

Baden, C., and S. Lecheler. 2012. Fleeting, fading, or far-reaching? A knowledge-based model of the persistence of framing effects. Communication Theory 22 (4): 359–382.

Berg, L., and A. Spehar. 2013. Swimming against the tide: Why Sweden supports increased labour mobility within and from outside the EU. Policy Studies 34 (2): 142–161.

Brewer, P. 2002. Framing, value words, and citizens’ explanations of their issue opinions. Political Communication 19 (3): 303–316.

Brewer, P. 2003. Values, political knowledge, and public opinion about gay rights: A framing-based account. Public Opinion Quarterly 67 (2): 173–201.

Burlacu, D., E. Immergut, M. Oskarson, and B. Rönnerstrand. 2018. The politics of credit claiming: Rights and recognition in health policy feedback. Social Policy & Administration 52 (4): 880–894.

Chong, D., and J. Druckman. 2007a. Framing theory. Annual Review Political Science 10 (1): 103–126.

Chong, D., and J. Druckman. 2007b. Framing public opinion in competitive democracies. American Political Science Review 101 (4): 637–655.

Chong, D., and J. Druckman. 2010. Dynamic public opinion: Communication effects over time. American Political Science Review 104 (4): 663–680.

Chong, D., and J. Druckman. 2013. Counterframing effects. The Journal of Politics 75 (1): 1–16.

Christensen, T., and P. Lægreid. 2020. The coronavirus crisis—crisis communication, meaning-making, and reputation management. International Public Management Journal 23 (5): 713–729.

Domke, D., D. Shah, and D. Wackman. 1998. Moral referendums: Values, news media, and the process of candidate choice. Political Communication 15 (3): 301–321.

Fuchs, D., and H.-D. Klingemann. 1990. The left-right schema. In Continuities in political action: A longitudinal study of political orientations in three western democracies, ed. M. Jennings and J. van Deth, 203–234. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Giddens, A. 1998. The Third Way: The Renewal of Social Democracy. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Green Party. 2014. Dags för en varmare politik!. Green Party election manifesto 2014, https://www.mp.se/sites/default/files/valmanifest_uppdaterad.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2021

Hayes, A. 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Highton, B. 2009. Revisiting the relationship between educational attainment and political sophistication. The Journal of Politics 71 (4): 1564–1576.

Imai, K., L. Keele, D. Tingley, and T. Yamamoto. 2011. Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review 105 (4): 765–789.

Jenkins-Smith, H., C. Silva, and R. Waterman. 2005. Micro- and macrolevel models of the presidential expectations gap. The Journal of Politics 67 (3): 690–715.

Jost, J., C. Federico, and J. Napier. 2009. Political ideology: Its structure, functions, and elective affinities. Annual Review of Psychology 60 (1): 307–337.

Karremans, J., and Z. Lefkofridi. 2020. Responsive versus responsible? Party democracy in times of crisis. Party Politics 26 (3): 271–279.

Lecheler, S., L. Bos, and R. Vliegenthart. 2015. The mediating role of emotions: News framing effects on opinions about immigration. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 92 (4): 812–838.

Lecheler, S., and C. de Vreese. 2019. News framing effects: Theory and practice. New York: Taylor & Francis.

Lecheler, S., and C. de Vreese. 2011. Getting real: The duration of framing effects. Journal of Communication 61 (5): 959–983.

Lecheler, S., and C. de Vreese. 2013. What a difference a day makes? The effects of repetitive and competitive news framing over time. Communication Research 40 (2): 147–175.

Left Party. 2009. Arbetskraftsinvandring. Left Party parliamentary bill, 5 October, https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/motion/arbetskraftsinvandring_GX02Sf326. Accessed 15 July 2021

Left Party. 2014. Vår välfärd är inte till salu. Left Party election manifesto 2014, https://www.vansterpartiet.se/assets/V%C3%A4nsterpartietValplattform2014.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2021

MacKinnon, D., J. Krull, and C. Lockwood. 2000. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science 1 (4): 173–181.

Malhotra, N., and Y. Margalit. 2014. Expectation setting and retrospective voting. Journal of Politics 76 (4): 1000–1016.

Manin, B., A. Przeworski, and S. Stokes. 1999. Elections and representation. In Democracy, accountability, and representation, ed. S. Stokes, A. Przeworski, and B. Manin, 29–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Markwat, N. 2021a. Pledge-based accountability: voter responses to fulfilled and broken election pledges. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg.

Markwat, N. 2021b. The policy-seeking voter: Evaluations of government performance beyond the economy. Springer Nature Social Sciences 1 (1): 1–21.

Morgeson, F. 2013. Expectations, disconfirmation, and citizen satisfaction with the US federal government: Testing and expanding the model. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 23 (2): 289–305.

Narud, H., and P. Esaiasson. 2013. Between-election democracy: The representative relationship after election day. Essex: ECPR Press.

Naurin, E., S. Soroka, and N. Markwat. 2019. Asymmetric accountability: An experimental investigation of biases in evaluations of governments’ election pledges. Comparative Political Studies 52 (13–14): 2207–2234.

Nelson, T., and J. Garst. 2005. Values-based political messages and persuasion: Relationships among speaker, recipient, and evoked values. Political Psychology 26 (4): 489–516.

Nelson, T., Z. Oxley, and R. Clawson. 1997. Toward a psychology of framing effects. Political Behavior 19 (3): 221–246.

Petty, R., and J. Cacioppo. 1986. Communication and Persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer.

Schemer, C., W. Wirth, and J. Matthes. 2012. Value resonance and value framing effects on voting intentions in direct-democratic campaigns. American Behavioral Scientist 56 (3): 334–352.

Seyd, B. 2016. Exploring political disappointment. Parliamentary Affairs 69 (2): 327–347.

Shanks, J., and W. Miller. 1990. Policy direction and performance evaluation: Complementary explanations of the Reagan elections. British Journal of Political Science 20 (2): 143–235.

Shen, F., and H. Hatfield-Edwards. 2005. Economic individualism, humanitarianism, and welfare reform: A value-based account of framing effects. Journal of Communication 55 (4): 795–809.

Slothuus, R. 2008. More than weighting cognitive importance: A dual-process model of issue framing effects. Political Psychology 29 (1): 1–28.

Slothuus, R. 2010. When can political parties lead public opinion? Evidence from a natural experiment. Political Communication 27 (2): 158–177.

Tavris, C., and E. Aronson. 2008. Mistakes were made (but not by me): Why we justify foolish beliefs, bad decisions, and hurtful acts. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The Alliance. 2013. Genomförandet av blåkortsdirektivet. The Alliance government Bill, 11 April, https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/FC7AE352-F689-4F0D-B0AD-5B1DA50EECCE. Accessed 15 July 2021

The Alliance. 2014. Vi Bygger Sverige. The Alliance election manifesto 2014. http://www.alliansen.se/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Vi-bygger-Sverige-Alliansens-valmanifest-2014-2018.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2021

The Liberals. 2014. Rösta för skolan. The Liberals Election manifesto 2014, http://www.forskasverige.se/wp-content/uploads/Folkpartiet-Valmanifest-2014.pdf. Accessed 15 July 2021

Thorisdottir, H., J. Jost, L. Ido, and P. Shrout. 2007. Psychological needs and values underlying left-right political orientation: Cross-national evidence from Eastern and Western Europe. The Public Opinion Quarterly 71 (2): 175–203.

Waterman, R., H. Jenkins-Smith, and C. Silva. 1999. The expectations gap thesis: Public attitudes toward an incumbent president. The Journal of Politics 61 (4): 944–966.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for comments provided by Peter Esaiasson, Elin Naurin, and the anonymous reviewers of Acta Politica. The author is also grateful to the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg, for their assistance with data collection.

Funding

The data collection was funded by the Laboratory of Opinion Research (LORE) at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, through their open application process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lindgren, E. (Un)Expected effects of policy rhetoric: value framing of policy proposals and voters’ reactions to subsequent information. Acta Polit 57, 836–863 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00229-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00229-0