Abstract

Comments on the role current federal deficits and recent policy have on state and local government budgets. Specifically, current policies and deficit levels may leave less room or political will for federal aid to state and local governments during the next economic downturn.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I come to the topic of federal budget deficits from a slightly different perspective than the other session participants. My interest is in what federal policy actions mean for state and local governments.

During the depths of the Great Recession, state and local governments survived in part because the federal government supplemented state and local revenues better than they had in prior recessions. Indeed, additional federal payments for healthcare (especially covering the costs for expanded Medicaid coverage), K-12 education, and infrastructure saved states across the country from even more economic pain.

However, I am not sure the federal government has the fiscal flexibility or the political will to act so decisively next time—and there will be a next time.

1 Why federal aid to state and local governments matters—and why it is currently at risk

State and local governments are a big part of our economy, generating roughly one out of seven jobs—more than any other sector, including retail and health care—and 11 percent of national GDP. But unlike the federal government, state and local governments are required to balance their budgets, and cannot deficit spend their way out of a recession on their own.

In fact, their need to balance budgets, combined with rising demand for state spending programs such as health insurance, unemployment benefits, and higher education, increases during an economic downturn. Thus without federal help, state spending cuts during a recession can further contract the economy. And while many states began the last recession with reserve funds, these were quickly spent given the severity of the economic downturn.

In short, federal funds not only help maintain state and local services, but employment and economic growth.

This is why I am so concerned by the large increases in federal deficits in a period of sustained—though modest—economic recovery. Specifically, the 2017 tax cut, commonly referred to as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), increased our federal debt by $1.9 trillion over the coming decade. Further, if the tax bill is extended and current changes are made permanent, that figure would grow at least by an additional $600 billion.

As I noted above, federal deficit spending makes sense if it assists state and local governments or otherwise stimulates the economy during a recession. Or, as Doug Elmendorf said, deficit spending is appropriate if it is used to fix our infrastructure, invest in individuals, or fund other programs that spur long-run economic growth.

But that is not what the recent Federal tax bill did. Instead, we increased our deficit level at a time when the economy was doing well, and there is little evidence the reduction in revenue will lead to more growth or private investment in either capital or workers. There were some positive parts of the tax bill, mostly on the corporate side, which hopefully will help make our tax system more competitive. But the cost of the total tax cut means we likely will have less flexibility to increase spending during the next downturn.

2 The current state of state and local governments—and an uncertain future

State finances are performing relatively well at the moment, and most states entered fiscal year 2019 with budget surpluses. In fact, Moody’s, S&P, the Philadelphia Fed, and our own analysis at the Urban Institute, all find states are generally in good fiscal shape. States are passing budgets on time and putting money away in their rainy-day funds.

But the last fiscal year was unique, possibly fleeting, and the future is full of uncertainly. In just over the past year or so, states finances were jolted by major federal tax changes, Supreme Court decisions that allowed for the collection of online sales taxes (South Dakota v. Wayfair Inc.) and legalized sports betting (Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association), and a volatile stock market. These events were mostly positive for state finances, but all create further unpredictability. And there are still long-term obligations (like public pension payments for retirees) looming.

Further, balanced budgets have not resulted in public employment gains. While federal action during the Great Recession helped keep state and local governments afloat, state and local governments were still forced to lay off workers and not fill vacancies. In fact, state and local employment levels are still not back to where they were before the Great Recession. Indeed, 10 years later the number of state and local workers was still lower than the number before the start of the recession.

Lower public employment could be evidence of states’ streamlining, and using more technology, and possibly being more efficient, or could reflect lower levels of government services. However, given most state and local spending is on salaries and people, it does mean that states would have less room to cut during the next downturn, leading to any downsizing that needs to occur leading to larger effects on the provision of services.

And there are uncertainties outside the state capitals. As our economy changes, how should our tax systems evolve? How should state job training programs adapt? How should public colleges and other programs and institutions for skill acquisition change? We need to think differently about how we invest for the future rather than thinking about how we just protect the vested interests of the past. Although speaking of the past, states still have $1.5 trillion in unfunded pension liabilities. There is much work to be done.

3 Federal help can improve state and local policy—but it might not next time

So how does this all fit together? In general, we need to think about how all of these public policies interact and affect our economic and fiscal bottom line. This means thinking about how economic policies and tax and spending decisions overlap and sometimes conflict with one another. For example, the economic benefit of lower corporate taxes can be undone by restrictive trade policy, or immigration limitations that make it hard for firms to hire appropriate workers. And some federal policy can be undone by changing state actions. This can include tax policies that offset federal changes, as noted below, or state cuts in services or increased taxes during a recession that offset federal stimulus.

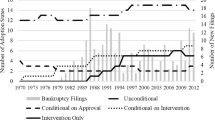

A federal–state or federal–local partnership could and should be part of this solution. One odd benefit of the last recession was that it improved some federal–state policies. Money was distributed throughout the country, both through increasing match rates for existing programs and more targeted funds to the places most affected by that downturn. Federal aid helped both red states and blue states, rich states and poor states, and rural areas and cities. Federal assistance during the Great Recession was much more effective than actions during the last two recessions. During the recession at the beginning of this century, largely related to the bursting of the dot-com bubble, effects were concentrated in specific states, and it was a relatively short downturn. Yet federal aid was distributed more slowly and largely on a per-capita basis to all states, though the formulas put into place in part led to the quicker roll-out during the Great Recession.

However, the politics surrounding TCJA might make collaboration seem less likely. Some states believe that the $10,000 annual cap on the federal deduction for state and local taxes was politically motivated and was a direct attack on their ability to raise revenues. Fearing that the loss of the deduction would cause a significant exodus of high-income taxpayers, they responded in kind by developing workarounds to the cap through the creation of charitable funds to support public social service programs (because charitable deductions are not subject to the cap) or taxing business rather than the income attributable to business owner or shareholders (because deductible business taxes are not subject to the cap). The Federal government responded, releasing guidelines that said any charitable deductions that were eligible for a state tax credit were not eligible for the federal deduction—affecting not only these new charitable incentives but also others that were already in place. This adversarial relationship does not bode well for future cooperative actions.

So could we see coordination across the federal and state and local governments following an economic downturn? It feels less likely, especially with the federal government swimming in debt for the foreseeable future. Further, I do not see there being a lot of appetite from the federal government to step in and fix state finances.

The lesson I would suggest to states is that given the recent surpluses (and depending on what revenues turn out to be this tax season) and, in addition to all the other uncertainties surrounding state and local government, it would be a prudent time for states to think hard about their fiscal futures and try to plan for the next five or ten-year period instead of just next year. That is, they would need to think about how they do their own recessionary smoothing in case the federal government forgets the lessons from the last recession.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These comments are largely based on remarks made at the 60th NABE Annual Meeting in Boston in a panel “The Outlook for US Public Debt and Its Fiscal and Economic Consequences.” I would like to thank the other session participants Jeff Holland, Lou Crandall, and Doug Elmendorf for a lively discussion and audience members for insightful questions and Richard Auxier, Howard Gleckman, Donald Marron, Mark Mazur, and Frank Sammartino for helpful comments. The views expressed and any errors are my own.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rueben, K. How federal deficits could hurt state and local governments. Bus Econ 54, 134–136 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-019-00126-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-019-00126-7