Abstract

This chapter shows that (1) the financial situation of the country in the 1990s deteriorated significantly; (2) the financial deterioration of the country in the 1990s had an adverse effect on local public finance, and the trinity reform was implemented before the adverse effect was corrected; and (3) the need for a Do-shu-system has increased due to the increase in “non-residential villages” or “non-residential areas” due to the decrease in migration.

This paper is based on a report made at the 44th Annual Meeting of the Japan Section of the Regional Science Association. I sincerely appreciate the contributions of the very valuable comments that I received from the debaters at the annual meeting, Prof. Hirotada Kono (professor emeritus at Tsukuba University) and Prof. Isao Hara (Hokkai Gakuen University), and the referees’ valuable indications.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The local systems in Japan have entered a period of great reform. The first Omnibus Decentralization Act was enacted in the year 2000. In December 2006, to facilitate a new Omnibus Decentralization Act, the Promotion of Decentralization Reform Act was enacted, and the Committee on the Promotion of Decentralization Reform was launched in April 2007. In terms of public finances, a trinity reform was carried out from 2004 to 2006, but economic reforms have not stopped there, and a new trinity reform is now set to be implemented. Regarding the revision of local tax allocations, a pillar of the trinity reform, not only has the scale of these allocations been reduced, but in April 2007, a new kind of tax allocation was implemented to simplify allocation standards. Because the trinity reform has reduced financial resources, we are currently in the midst of a great Heisei period merging of municipal governments for reformation purposes. Discussion around reforming the prefectures by integrating them into a smaller number of states has also begun in earnest. Furthermore, to facilitate plans for national land development, the former Comprehensive National Land Development Act was revised in 2005 and was renamed the National Spatial Planning Act. Thus, the reform of various local government systems is now underway.

In this paper, I clarify that (1) a lack of moderation in the 1990s precipitated a change in tone in public finances, (2) fiscal measures conducted in the 1990s took a form that dragged in local governments and therefore harmed local public finances, and (3) before this harm could be corrected it was first considerably worsened through the implementation of the trinity reforms. Furthermore, I identify the possibility that the decentralization of power and integration of the prefectures may produce new problems if they are implemented without assurances of economic support.

2 The Changing Tone of National Finances

2.1 The Rapid Increase in the National Debt

The national finances deviated from the doctrine of balanced budgets when government bonds were issued in the revised budget for the 1965 fiscal year. Following the inclusion of the issuance of construction bonds in the initial budget for the following fiscal year, the issuance of special bonds known as deficit bonds were included in the revised budget for 1975 (the 50th year of the Showa era). These special bonds were scheduled to be repaid in 10 years. However, the repayment period was extended to 60 years, similar to construction bonds, because the poor economic climate of 1985 had resulted in insufficient financial resources (Showa 60). Furthermore, the issuance of refunding bonds was permitted to ensure the necessary financial resource availability. However, efforts were made to suspend the issuance of special bonds as soon as possible, an objective that was realized in the fiscal year 1990 (Heisei 2) after the fortunate support of the natural increase in tax revenues caused by the bubble economy.

In the 1990s, the economic climate worsened because of the collapse of the bubble economy, and the Heisei recession began. However, the government emphasized that it had been able to bring the issuance of special bonds to zero through great pains and was reluctant to embark on new ambitious fiscal policies. Therefore, monetary policy replaced fiscal policy, with cuts made to the official discount rate. However, monetary policy was insufficient as an economic measure following the collapse of the bubble and the economic climate continued to worsen. Criticized for their inept response to the Heisei recession, the era of single-party government by the LDP collapsed with the establishment of a coalition government in August 1993 (Heisei 5).

The confusion of Japanese politics in the 1990s destabilized the administration; financial rules loosened, the budget deficit expanded each year, and the national debt increased rapidly, resulting in fears of the financial collapse of Japan (Kaizuka and Krueger 2007, pp. 5–20).

2.2 A Change in the Administration of Public Finances

A detailed look at the administration of public finances in the 1990s highlights a variety of problems. Among these, the next five points are particularly important. First, despite the considerable slump in tax revenues, a review of annual expenditure was postponed. Second, initial budgets attempted to maintain a zero ceiling. Third, full-scale economic policy was conducted in revised budgets (Fujioka 2009). Fourth, fiscal policy measures were conducted in a form that dragged in municipal governments. Fifth, loans to special accounts for local tax allocations and transfer taxes were used as local fiscal measures to increase financial resources (Higo and Nakagawa 2001, pp. 15–17). These five problem points were instrumental in causing the accumulation of a large national debt. In this sense, it might be said that the change in the tone of public finances occurred because of a loss of fiscal moderation.

A direction for fiscal reforms was revealed when it became impossible to ignore the change in national finances. The reforms included, first, the establishment of a framework for the total national annual expenditure, exemplified by the fiscal structure reforms implemented by the Hashimoto Cabinet. A second reform was a reduction in the amount of local tax allocations and subsidies to local governments, which was realized in the trinity reforms.Footnote 1 Third, local governments were asked to take on tasks previously handled at the national level, actualizing the decentralization of power (Hayashi 2005, pp. 27–41). Fourth, to reinforce local power, municipalities were merged and the integration of the prefectures came under consideration as a way to accomplish this more fully.Footnote 2 Fifth, the national development scheme that had been used for local development since the end of WWII was suspended and replaced by the introduction of a new local development scheme, the National Spatial Plan.

2.3 Problems with the Reforms

Despite having been appropriate for their respective individual goals, a comprehensive examination of these reforms raises questions. First, considering that the level of the burden taken on by the citizenry, including the social security burden, is still lower than the burden in European nations, one problem is that the reforms only rashly reduced the scale of annual expenditure. The relative relationship between reduced expenditure and increases in revenue caused by an increase in taxes must be considered. In this sense, including a consideration of tax increases in the combined reform of yearly revenue and expenditure is appropriate. Instead, they do not go beyond a mid-term perspective in that they merely aim to achieve the limited goal of primary balance. Second, the trinity reforms (Sato 2007, pp. 2–50) failed to address the problem of insufficient independent sources of local government funds. Therefore, an examination of not only the transfer of funds from the nation, but also increases in local taxes is necessary (Kuroda 2007, pp. 126–158). Third, whether long-centralized government activities can be swiftly decentralized is under question. Local government independence is required, which includes the problem of the lack of powers transferred from the nation. Fourth, whether the integration of the prefectures can stimulate independence in local governments is similarly under question. Securing economic power is necessary to increase this independence, but if the integration of the prefectures is implemented without it, then the disparities between regions may increase further.Footnote 3 Fifth, the regional division assumed in the prefectural integration system does not necessarily align with the regional division in the National Spatial Plan. As a result, the fear remains that further local development may be inefficient; this includes the division of government roles.

There are other important problems besides these. First, if economic activity does not recover, the various reforms will have been largely ineffective. The fact that the maintenance of annual expenditure is impossible if tax revenue cannot be collected also makes this clear. Second, economic activity is now strongly influenced by the effects of globalization. As a result, companies are able to cross national borders in choosing the optimal location for their business. Many local governments have failed by entrusting their hopes to offering reduced local taxes and subsidies in a bid to attract companies to their region. Third, the relative lack and loosening or abolition of restrictions is damaging. For example, the closed-off nature of Japanese agriculture and the resulting inaccessibility of Japanese agricultural products have hampered the conclusion of free trade agreements (FTAs) and economic partnership agreements (EPAs) that would promote the liberalization of manufactured goods. Japan is therefore disadvantaged in its attempts to compete not only with advanced countries, but also with developing ones.

Thus, although the reforms were intended to be beneficial, their lack of consistency and degree of implementation, among other problems, have instead led to weaker results.

Correction rate of general account expenditure. (Based on data on general account initial and revised budgets in “Chapter 5 Public Finances” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Japan Statistics Bureau, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

3 Initial and Revised Budgets

3.1 Introducing the Correction Rate

Economic policy measures sometimes use initial budgets and sometimes revised budgets. If they use an initial budget, then the scale of economic measures can be understood by looking at the growth rate of the previous fiscal year’s initial budget (or in some cases, revised budget). However, the growth rate from the previous fiscal year’s revised budget is not appropriate if the policy measures employ a revised budget. We therefore introduce a “correction rate” as an indicator of how much the initial and revised budgets differ. The correction rate is obtained by subtracting the initial budget from the revised budget and then dividing by the initial budget.

This correction rate allows us to relatively compare the relationship between the size of the revised budget conducted during the fiscal year and the scale of the initial budget. A large correction rate means that a large revision was conducted in proportion to the scale of the budget. It may, therefore, indicate the scale of new government activity conducted during the fiscal year.

The correction rates for general account total annual expenditures for each fiscal year are shown in Fig. 9.1, illustrating that the correction rate of the nation’s finances increased considerably in the middle of the 1970s, at the end of the 1980s, and in the 1990s during the Heisei recession. We determine the reason for this by reexamining the change between the taxes and revenue in the initial and revised budgets as shown in Fig. 9.2. According to Fig. 9.2, the bubble economy period from the middle of the 1980s until the beginning of the 1990s produced a significant natural increase in tax revenues during the fiscal year. In fact, for the four fiscal years from 1987 to 1990, the revised budget included more tax revenue than the initial budget. Government expenditures were increased in the revised budget to consume this tax revenue and the correction rate therefore grew larger.

Tax and stamp revenues. (Based on data on general account initial and revised budgets in “Chapter 5 Public Finances” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Japan Statistics Bureau, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

The middle of the 1970s saw the oil crisis and the accompanying recession. As a result, excluding 1976, between 1975 and 1978 tax revenue in the revised budget decreased in comparison with that in the initial budget. Similarly, the Heisei recession in the 1990s following the bubble collapse resulted in a smaller tax revenue in the revised budget in comparison with the initial budget from 1991 to 1999, excluding 1996. Accordingly, the correction rate increased as a result of fiscal policy measures taken during both periods. Furthermore, during the Heisei recession, there were periods of continuous implementation of large-scale policy measures during the fiscal year. That is, in fiscal years 1993, 1995, 1998, and 1999, large-scale revised budgets were assembled for the fiscal policy purposes and the correction rate grew larger during these fiscal years.

From these facts, it can be said that full-scale economic policy measures were implemented twice in the post-war Japanese economy: during the period of slow growth that followed the oil crisis in the 1970s (October 1973) and during the Heisei recession after the collapse of the bubble in the 1990s (February 1991). However, despite the increased growth rate in the initial budget during the oil crisis, the scale of economic measures in the revised budget was comparatively small. Accordingly, we can say that the economic measures in the revised budget exceeded the growth rate in the initial budget only during the 1990s.

Growth rate of government bond and correction. (Based on data on general account initial and revised budgets in “Chapter 5 Public Finances” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Japan Statistics Bureau, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

3.2 Economic Monetary Policy and the Issuance of Government Bonds

Government bonds are issued to procure the necessary financial resources to implement policy measures, which are not only implemented in the initial budget, but also in the revised budget. Therefore, Fig. 9.3 shows the growth rate of the issuance of government bonds in the initial budget and the corrected rate of the issuance of government bonds. The growth rate and corrected rate are relatively small from the late 1960s to the 1970s because of the government bond issuance restraint policy of the Ministry of Finance. However, in August 1971, antirecession policies were implemented because of the Nixon Shock, as it was predicted that the Japanese economy would enter a recession. This resulted in increases in the corrected rate for the issuance of government bonds in 1971 and the growth rate for the issuance of government bonds in the initial budget of 1972. However, in terms of the issuance of government bonds, no economic monetary policy was undertaken between the first oil shock in 1973 and the initial budget of 1975. Finally, policy measures were once again undertaken in the revised budget for fiscal year 1975. This continued until the initial budget for the 1979 fiscal year. However, there was no further implementation beginning with the revised budget for the 1979 fiscal year, and, regardless of the second oil crisis in 1979, none were implemented until the initial budget of the 1982 fiscal year. The corrected rate for the issuance of government bonds in fiscal year 1982 and the initial budget for the issuance of government bonds in fiscal year 1983 both increased, and although measures were implemented, from 1984 to 1991 the growth rate of the issuance of government bonds continued to be negative. Starting with the revised budget in fiscal year 1991, the growth rate for the issuance of government bonds in initial and revised budgets for the implementation of policy measures increased.

In the 1990s government bonds were issued on a large scale in the name of economic policy measures each fiscal year, so the national debt increased rapidly. The national debt was expected to reach 547.722 trillion JPY in 2007.

4 Worsening Local Finances

4.1 The Initial and Revised Budgets of Local Governments

To begin, it must be noted that local government budgets have different characteristics than national budgets. The initial budgets of local governments are called “skeleton budgets” and are compiled without sufficient information. This is because, despite the finances of local governments being largely dependent on subsidies and local tax allocations, the official amount of these allocations cannot be confirmed until some later point in the fiscal year. When the receipt of a given subsidy or other source of revenue from the nation is confirmed, a revised budget is compiled. Revised budgets are therefore compiled often. Because of national circumstances, subsidies may become available as late as March, meaning that a revised budget must be hurriedly compiled at the end of March. Accordingly, the compilation of revised budgets for local governments is different than the compilation of a revised budget for the nation and does not reflect the intentions of the local government. As a result, the consideration of correction rates, which has meaning at the national level, is not appropriate for local governments.

Furthermore, because the compilation of local government budgets may be controlled by subsidies or the allocation of taxes, it is even possible for the behavior of the local government to be manipulated by national trends or inclinations.

4.2 The Relationship Between Public Works Spending and Normal Construction Funds

To confirm the use of the normal construction funds of local government finances in national economic policy measures, we examine the public works spending in the initial budget and revised budgets and its relationship with local governments’ normal construction funds.

To begin, examining these three correlations in budgets from fiscal years 1965–2004, the correlation between normal construction funds and public works spending in revised budgets (0.959) is slightly higher than the correlation with public works spending in initial budgets (0.943), but the difference is not large. However, looking at the initial and revised budgets for public works spending from fiscal year 1990 to fiscal year 2000 and their correlations with normal construction spending, it can be seen that the correlation between normal construction spending and public works spending is clearly higher (0.728) for public works spending in revised budgets than public works spending in initial budgets (0.554). Accordingly, normal construction funds may be manipulated by the nation to cooperate with economic policy measures.

4.3 The Role of Local Tax Allocations

Local tax allocations are a general subsidy system established as a national special account system that transfers funds from the national government to local governments (Ishihara 2000). What is important in the role of the local tax allocation is its financial adjustment function, which corrects disparities in resources between local public entities. Its next most important function is the function of assuring financial resources. However, with respect to the function of assuring financial resources, a problem has been identified in which local governments receive tax allocation distributions in proportion to how small they are, meaning that smaller governments receive a wealth of public services (Okamoto 2002, pp. 57–63). The same problem exists for the other important role of local tax allocations, the financial resources adjustment function.

For example, according to the results of the “Annual Local Government Financial Statistics Report” (2006 edition), of the 47 prefectures, Tokyo was the only government body not allocated ordinary tax allocations. The other 46 prefectures were distributed some local tax allocations. Thus, the fact that all prefectures with one exception were subject to allocations must be called a major flaw in the system.

In order to examine how disparities changed as a result of adjustments caused by the local tax allocation system, we define an indicator called the degree of deviation from the mean.

Degree of deviation from the mean is:

Based on this indicator, it is possible to compare local governments with large- and small-scale finances in the same way.

According to the result values for prefectures in 2004, in contrast to the prior degree of deviation in local taxes per resident capita of 0.72, the degree of deviation from the mean of the “later per resident capita local tax + local tax allocation + local special allocation funds” was 0.9. That is, the prior degree of deviation of 0.72 was expanded to 0.9 after the allocations. Accordingly, the local tax allocation system is not fulfilling its function of adjusting financial resources and is instead expanding differences between regions.Footnote 4

As for why the local tax allocation system is not fulfilling the financial resources adjustment function, it seems that it has come to perform excessive transfers of financial resources through the expansion of the financial security system. Accordingly, it is important to curtail the financial security function of the present local tax allocation system to bring back the financial resources adjustment function.Footnote 5

4.4 Special Accounts in the Local Tax Allocation System

Why has the local tax allocation system changed from fulfilling a financial resources adjustment function to a financial security function? This is because, during the long Heisei recession of the 1990s, local governments suffered from a lack of financial resources. The Japanese government held huge fiscal deficits and could only obtain financial resources through the issuance of government bonds, initially conducting a policy of public investment and later increasing the local tax allocation. Direct fiscal policy measures could be taken by expanding national expenditure on public works. However, the discussion becomes somewhat complicated with respect to increases in local tax allocations. This is because the local tax allocation system has adopted a special accounting system in which funds are transferred from the national treasury to a special account and then distributed from that account to each local government as local tax allocations.

The funds for local tax allocation are transferred into a special account, but if these resources are insufficient then the special account may also allowed obtain its own loans. Accordingly, it is possible that the amount of national local tax-allocation expenditure and the local tax allocation distributed to local governments do not coincide. Therefore, by comparing the amount of national expenditure on local tax allocation and the amount of local tax allocation distributed to local governments, we can examine how the special account for local tax allocations has been managed. Therefore, the amount of local tax allocation assumed in local fiscal plans will be used as the distributed amount of local tax allocations. We then examine the deviation rate between the amount of allocated tax in the local fiscal plans and the national expenditure on local tax allocation.

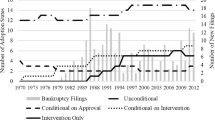

Changes in this deviation rate are as shown in Fig. 9.4.

Local allocation tax and divergence rate. (Based on data on local tax allocations from “Chapter 5 Public Finances” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Japan Statistics Bureau and “Local Financial Plans” of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

As is clear from Fig. 9.4, the deviation rate for local tax allocations is high briefly in the 1970s, but from fiscal year 1984 onward, it instead becomes negative. It then continues to be negative until the beginning of the 1990s. In the 1990s, it once again increases before becoming negative in 2004. This shows that even if the special accounts for local tax allocations borrow money to increase the amount distributed to local governments, over the long term this borrowing eventually stops, after which the amount distributed to local governments decreases in order to repay the borrowed amount. In addition, the period during which the disagreement rate for local tax allocation is negative continues for as long as it takes the loans to be repaid. During the 1980s exactly this happened, as local tax allocations that should have been distributed to local governments were reduced to aid in the repayment of loans. Furthermore, similar to the 1970s, the 1990s were a period when local tax allocations were distributed widely to local governments through borrowing in the special accounts. In the 2000s, this kind of irregular financial management was short-lived, instead turning more toward the repayment of the loans borrowed by the special accounts. As a result, the amount of local tax allocations distributed to local governments was smaller than the amount of national expenditures on local tax allocations.

5 Changes in Local Populations

5.1 Population Increases

Population increases are composed of two elements: natural and social increases. Whether the population of a given area is increasing or not is determined by whether the combined total of natural and social increases is positive or negative. A high natural increase in population occurred in Japan during the period of high economic growth, but the social increases were far larger than this natural increase. The migration rate at this time was usually above 7% and sometimes even above 8%. This means that the entire population of Japan moved once within a 12.5-year period. This was truly a period of great migration. Today, the migration rate has fallen to only 2.35% in 2006. This means that for the national population to move once it would take 42.6 years. Yet, an annual migration of 5.56 million people is still notable. Population migration is a vital factor in regional development.

5.2 The Population Increase Rate

The increase rates of the post-war population for the three major metropolitan areas (the Tokyo area, Osaka area, and Nagoya area) and the regional areas (prefectures aside from the three major metropolitan areas) are shown in Fig. 9.5.

Population growth rate. (Created from the author based on data in Table 3 of “Chapter 2 Population” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Japan Statistics Bureau, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

The three major metropolitan areas have a significant population increase rate from the 1960s until the first half of the 1970s during the period of rapid economic growth. The Taiheiyo Belt was formed during this period. Cued by the first oil shock, the population increase rate falls rapidly beginning in the second half of the 1970s up until 1980. Entering the 1980s, it rises slightly. However, from about the middle of the 1980s, it once again begins to fall, and during the Heisei recession after the collapse of the bubble, it falls once again. Beginning in 1995, the rate rises again, after which it tends to continue to rise.

The population increase rate in the regional areas is low in the 1960s, but begins to increase in the 1970s and stays at a high level throughout the decade. However, entering the 1980s, the regional rate falls to a much lower level than that in the three major metropolitan areas. During the bubble period, it maintains a low level of approximately 0.1%. Once the bubble collapses and the Heisei recession begins, it rises slightly, exceeding the metropolitan rate marginally in both 1994 and 1995. However, after 1995, the regional rate begins to fall, reaching a negative growth rate in 2000.

The population increase rate in Tokyo begins to fall after the rapid economic growth period and maintains a negative growth rate from 1977 until 1980, becoming positive again in the 1980s. This was the period of overconcentration in Tokyo. However, when the bubble economy begins, Tokyo’s population increase rate falls, only returning to a positive growth rate in 1991, with an otherwise negative rate from 1987 until 1996. From 1997 onward it becomes positive and remains positive during the 2000s. Today, the population increase rate is even higher than during Tokyo’s overconcentration period, signaling a new overconcentration period in Tokyo.

5.3 In-Migration Rates in Large Cities

The in-migration rate in 16 large cities in 2005 and 2006 is shown in Fig. 9.6. It is clear from Fig. 9.6 that in 2005 and 2006, Yokohama, Shizuoka, Sapporo, Kawasaki, Sendai, the special wards of Tokyo, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Chiba, Kobe, Kitakyushu, and others have positive in-migration rates. In comparison, Fukuoka, Osaka, Nagoya, Saitama, and others have negative in-migration rates. Looking only at these numbers, Fukuoka, Nagoya, Saitama, and other cities have populations that are socially decreasing and might be considered regions in decline. However, looking at in-migration rates by prefecture, the prefectures where each of these cities is located all have increasing populations. Accordingly, it is appropriate to think of the residents of these cities as in the process of moving from the city center to the suburbs. That is, these cities have entered a new stage of population movement.

Population growth rate of 16 major cities. (Created from the author based on data in Table 3 of “Chapter 2 Population” of the “Long-term Japan Statistical Series” at the homepage of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, http://www.stat.go.jp/data/guide/download/index.htm)

Thus, there is currently a concentration of the population in Japan’s central cities.

5.4 The Merging of Municipalities and Discussions Around Integration of Prefectures (Introducing a Do-Shu System)

Today, the great merging of the Heisei era is taking place. That is, given the expectations of an increase in municipalities that cannot continue resident services because of a future decrease in population, attempts are being made to increase the efficiency of administration through the merging of municipalities to deal with the lack of financial resources. However, municipal mergers that take place without taking steps to deal with the negative assets, or municipal bonds, that they inherit in the process do not contribute to improving financial circumstances. An increase in efficiency is being attempted through these mergers, but there is no guarantee that their effects will be sufficient to offset these negative assets (Miyazaki 2008, pp. 17–18).

The future financial burden represented by municipal bonds can to some extent be seen in local tax allocations. However, even if the scale of local tax allocations does not change, if the portion of financial resources used to repay municipal bonds increases, the remaining financial resources will diminish. If the scale of the local tax allocations is curtailed in the future, the portion of financial resources available for purposes aside from municipal bonds will decrease even further. As such, these bonds weigh heavily on local governments.

In addition, even when municipal mergers do take place, it is necessary to pay attention to the possibility of an inverse relationship between increasing administration efficiency and improving the quality of administrative services. Meticulous administrative services provided to residents are relative to how small the provisioning government is.Footnote 6 If the scale of the government increases, the possibility that problems with administrative services may occur also increases. Accordingly, in regions where municipal mergers have taken place, it is necessary to be prepared for a reduction in administrative services.

One problem with the municipal mergers that have recently taken place is that the municipalities themselves have not supported them. They have instead taken place for reasons of national convenience. Furthermore, they have been executed in a manner that does not search for the most appropriate combination of municipalities and instead merely combines municipalities wherever possible. However, considering the future full-scale decrease in population, it is preferable to implement municipal mergers strategically. The merger standards in these cases may or may not be connected to increases in economic power. If the mergers that do occur do not increase the economic power of the municipality, then they will cause outfluxes of residents and a decrease in population. As a result, any benefits of the merger may be offset by further decreases in efficiency.

Discussions around integrating the prefectures (introducing a Do-Shu system) are based on the same principle as municipal mergers: that merging prefectures and delegating national authority will encourage increases in the efficiency of administration in local governments (Fujita 2006, pp. 143–147). However, as with municipal mergers, there is no guarantee that administrative services and efficiency will be improved simply by integrating prefectures. In particular, the integration of prefectures without economic support will lead to entities that cannot support themselves, with most of the integrated states declining in influence.Footnote 7

The government is introducing other policies for regional regeneration aside from municipal mergers and the introduction of integrated prefectures. One of these is the Regional Revitalization Plan which was implemented beginning in April 2005. The government is also recognizing special deregulation zones, which were introduced around the same time, as experimental zones where regulations are loosened. However, a characteristic of this system is that it has a narrow range of operation. In comparison, the Regional Revitalization Plan allows for the delegation of authority, and the simplification of administrative procedures, among others, permitting a somewhat broad range of operation. As a part of the Regional Revitalization Plan, cross-ministry grants known as Regional Revitalization Infrastructure Reinforcement Grants have been established. However, as these subsidies are strongly dependent on national authority, they cannot be said to follow the trend towards decentralization.

5.5 Important Points Regarding Prefectural Integration

Considering that population concentration is occurring in the central cities of each region, the partition of regions in integrating the prefectures should be based on these shifts in population. By partitioning cities with concentrated populations as administrative centers, it will be possible to divide regions into integrated prefectures from a functional standpoint. For example, Shimonoseki is often classified as part of the Chugoku/Shikoku region, when its economic relationships are actually stronger with Fukuoka. Accordingly, classifying Shimonoseki as part of the Kyushu region will raise economic interdependence.

6 Conclusion

Japan’s local governments are currently facing many problems, the basis of which is economic. Accordingly, systemic reforms that are not accompanied by measures to resolve these economic problems will eventually end in failure. The current economic problems are strongly influenced by economic globalization, which must be considered when engaging with the problems of municipal mergers and prefectural integration.

Even if integrated prefectures are introduced, these newly formed states will merely lose population and have difficulty implementing independent administrative activities if they lack economic power. Accordingly, in introducing an integrated prefecture system, it is preferable to partition regions not according to the current population distribution but instead by promoting “regional overconcentration” centered on large cities whose population will become more concentrated in the future.

Based on the circumstances of loans in national and regional finances, financial flexibility is not expected to be possible for a number of years, so inducing population movements to certain regions by shuffling financial resources is not a desirable policy. It is therefore necessary to leave this redistribution to population movements caused by economic power and to endorse regional overconcentration and take it into account in considering regional policy.

Notes

- 1.

Konishi (2003), describes local tax allocation reforms based on reductions as preferable, and examines how and why the local tax allocation system is flawed. Regarding policies for reducing the amount of local tax allocations and shouldering these debts through extraordinary financial measure loans, see Umehara (2002).

- 2.

- 3.

Doi (2007) contains a theory supporting a transition to integrated prefectures (pp. 1–3) as well as an explanation of how a financial adjustment system between the newly formed states would function (p. 10).

- 4.

An analysis of the fiscal adjustment effects of normal tax allocation at the municipal level is contained in Chapter 4 of Takabayashi (2005).

- 5.

Yamashita et al. (2002) empirically suggest that the local tax allocation system may present a moral hazard for local governments.

- 6.

See Oates (1972) for the decentralization theorem that forms a basis for decentralization of power.

- 7.

Hashimoto and Yoshida (2004) argue that, based on the current system of government finances, even if an integrated prefecture system were introduced, all the newly formed states except for Tokyo would lack sufficient financial resources.

References

Boadway R (2004) And keen, “redistribution”. In: Atkinson AB, Bourguignon F (eds) The handbook of income distribution 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 677–789

Doi T (2007) A fiscal examination of the integrated prefecture system. In: JPSA 2007 annual research conference report, Oct 2007, pp 1–15

Fujioka A (2009) Changes in the structure of public works costs in initial and revised budgets. Q J Rissho Econ Soc 58(3):121–149

Fujita Y (2006) From municipal mergers to integrated Prefectures. Reg Stud 3(2):143–153

Hashimoto K, Yoshida M (2004) On the possibilities of regional fiscal reform and an integrated prefecture system. PRI Discussion Paper Series (No.04A-12), May 2004, p 21

Hayashi Y (2005) The economics of the new decentralization of power. Nihon Hyoronsha, May 2005, p 290

Hayashi K (2008) Problems with the integrated prefecture system from a legal perspective. Gyosei, Dec 2008, p 278

Higo M, Nakagawa Y (2001) Problems with local independence projects and the local tax allocation system–the positive and negative effects of providing financial support to local municipalities using local tax allocations. Bank of Japan Research and Statistics Bureau, pp 1–64

Ishihara N (2000) A new regional finance adjustment system theory. Gyosei, March 2000, p 546

Ito T (2009) The failures of power decentralization: the difficulties of integrated states. Gentosha Renaissance, March 2009, p 241

Kaizuka K, Krueger AO (eds) (2007) Tackling Japan’s fiscal challenges: strategies to cope with high public debt and population aging. Nikkei Publishing, Tokyo, p 228

Konishi S (2003) Directionality for the reform of local tax allocations. Sanken Ronshu (Kwansei Gakuin University) No. 30, March 2003, pp 1–12

Kuroda B (ed) (2007) The trinity reforms and the future–local taxes and local tax allocations. Gyosei, Jan 2007, p 292

Matsumoto H (ed) (2006) Studies of local autonomy systems. In The integrated prefecture system handbook. Gyosei, p 343

Miyazaki T (2008) Local tax allocations and municipal mergers. Hitotsubashi University Research Unit for Statistical Analysis in Social Sciences, Discussion Paper Series 239, Feb 2008, pp 1–26

Oates WE (1972) Fiscal Federalism. Harcourt Brace Javanovich, New York, pp 15–63

Okamoto M (2002) On the reform of regional finances. Gyosei, May 2002, p 245

Sato F (2007) The trinity reforms and the future–a general discussion and the burden placed on state assistance. Gyosei, May 2007, pp 236

Takabayashi K (2005) An analysis of fiscal disparities between regions. Yuhikaku, Feb 2005, p 234

The “White Paper on Local Public Finances” (n.d.) Annual Local Government Financial Statistics Report. “Annual System of National Accounts Report,” and “Public Financial Statistics” for each fiscal year have been used

Umehara E (2002) A study of measures to reduce local tax allocations and institute extraordinary financial measure loans. J Econ Osaka Univ 53(4):239–267

Yamashita K, Akai N, Sato M (2002) Latent incentive effects in local tax allocation systems. Policy Research Institute, Ministry of Finance. Financial Review, Feb 2002, pp 1–26

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fujioka, A. (2022). Budget Deficits of the Central Government and the Decentralization of Local Governments. In: Higano, Y., Kiminami, L., Ishibashi, K. (eds) New Frontiers of Policy Evaluation in Regional Science. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives, vol 52. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4501-3_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4501-3_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-16-4500-6

Online ISBN: 978-981-16-4501-3

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)