Abstract

The communist AKEL (Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού) party governed the Republic of Cyprus from February 2008 to February 2013. During this period, AKEL had to deal with grave economic problems. This article uses the European Elections Study (2009) data and presents a statistical model that explains up to 70 per cent of the variance. We show that retrospective sociotropic evaluation of the economy by the Greek Cypriots has a significant effect on their intention to vote or not for the incumbent party. On the basis of this result, one may argue that the considerable amount of votes lost by AKEL in February 2013 presidential elections could be mainly because of the deteriorating economic situation since the party took office in February 2008.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

AKEL (Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού), the main left-wing party in the Republic of Cyprus is currently the second biggest party. Founded in 1926, AKEL defines itself as a communist party. However, AKEL has been on a slow path of transformation toward becoming a social democratic party since the 1990s (Charalambous, 2007, pp. 432–433; Dunphy and Bale, 2007, p. 29; Christophorou, 2008, p. 231). AKEL came to power first time on 24 February 2008. The party’s clear victory and 5 years of incumbency ended up with substantial decrease in its vote share in the second round of the presidential election on 24 February 2013. AKEL’s election bid resulted in a bitter loss to the centre-right candidate Nikos Anastasiades. Before the elections, AKEL had to deal with grave economic problems. This article shows that these economic issues could be one of the main deciding factors in AKEL’s loss in share of its votes in the February 2013 election. First, we describe the deteriorating economic situation during AKEL’s incumbency. Then, we use the European Elections Study (2009) data to show that retrospective evaluation of the economy by the Greek Cypriots has a significant effect on their intention to vote or not for the incumbent party.

This article aims to contribute to knowledge in three different ways. First, it contributes to the emerging literature on the domestic politics of the Republic of Cyprus. In particular, it adds to the debate on the transformation of politics, which manifested itself in declining voter turnout and reappearance of far right as a result of the economic crisis (Christophorou, 2012; Kanol, 2013; Katsourides, 2013). Second, it is the first research that tests economic voting in Cyprus. Although focus on economic voting has recently shifted toward Southern European countries (Lewis-Beck and Nadeau, 2012), Cyprus is still exempted from scholarly analysis. Third, it provides results for comparing the magnitude of economic voting in times of economic crisis once new data become available. New data will cover the period after the catastrophic economic crisis in Cyprus that spurred the Eurozone area. Thus, this article goes beyond presenting the first evidence for economic voting in Cyprus or explaining the vote intention in February 2013 election for AKEL. It also presents evidence in favor of the economic voting hypothesis and provides results that can contribute to the discussion about the variance in the magnitude of economic voting during economic crises (see Singer, 2011a; Anderson and Hecht, 2012; Belluci et al, 2012; Marsh and Mikhaylov, 2012; Nezi, 2012).

Economic Woes of the Republic of Cyprus

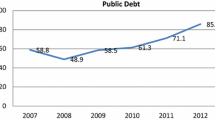

The economic situation in the Republic of Cyprus deteriorated during AKEL’s term in office which started on 24 February 2008 and ended on 24 February 2013. Public debt monotonicly increased from 48.9 per cent in 2008 to 85.8 per cent in 2012 (see Figure 1) and unemployment rate monotonicly increased from 4.2 per cent in February 2008 to 14.8 per cent in February 2013 (see Figure 2). These statistics were not the only disturbing news. A huge blast of ammunitions in July 2011 next to a power plant left the country with limited electricity supply for a long period. This hit the deteriorating economy even further and created pressure on the government (Theodolou, 2011). Dependence of the financial sector on stumbling Greece exacerbated these serious problems. Cyprus’ credit rating was reduced to junk status in June 2012 by Fitch. This was followed by similar moves from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (Howarth, 2012; USA Today, 2012; Hufftington Post, 2012). The country was seeking bailout money both from the European Union (EU) and the Russian Federation during the incumbency of the AKEL government.

Total public debt (% of GDP, 2007–2012).

Source: EUROSTAT (2013a).

Unemployment rate (seasonally adjusted, 2007–2013).

Source: EUROSTAT (2013b, 2013c).

In the European Commission reports (2013), two points emerged that had to be addressed immediately. First, the imperative need for the recapitalization of banks in Cyprus and second, fiscal consolidation. The boards of the two largest banks in Cyprus (Bank of Cyprus and Cyprus Popular Bank) proceeded to buy Greek bonds in the middle of the Greek economic crisis. The result of this move was the spillover of the Greek crisis into the Cypriot economy (Agence France-Presse, 2013). The opposition accused the government for not being able to manage the economic crisis. On the other hand, the communist president accused the former governor of the Central Bank Athanasios Orphanides for not properly informing him in regard to the seriousness of the issue (Nicolaides, 2012). At a meeting between the Hellenic American Bankers Association and the Cyprus-US Chamber of Commerce, the governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus (Panicos Demetriades) stated that the Cypriot bailout as a proportion of the country’s total GDP would be the largest ever after the Indonesian bailout of 1997 (Famagusta Gazette, 2013a).

According to the estimations by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Cypriot banks needed around €10–12 billion to recover. After simultaneous downgrades from the three credit rating agencies, the Cypriot bonds have fallen into the category of junk and the country has not been able to borrow from the international markets to finance state expenses. Because of these developments, the government of the Republic of Cyprus approached Russia and managed to get a loan worth of €2.5 billion. Later, the Cypriot government attempted to receive an additional loan from Russia of €5 billion. This time, Russia denied the Cypriot government’s demand. This demonstrates the difficult economic situation that existed on the island. Moscow did not intend to offer an additional loan, doubting the Cypriot government’s ability to pay it back in the near future. Moscow repeatedly stressed that any assistance to the Republic of Cyprus should be in partnership with the EU (Tanas and Arkhipov, 2013).

The immediate spending cuts that were asked to be implemented by the Troika (The EU, The European Central Bank and the IMF) were mainly in the public sector. The biggest reaction in relation to measures taken by the Troika came from the workers in the public sector. The Troika declared that other than the banking problem, the ‘big state’ is creating a headache for the island’s economy (Famagusta Gazette, 2013b). When in power, the communist party stated many times that they would not accept the cost of crisis to be paid by workers. They argued that the neo-liberal measures proposed by the Troika could guide the country into a lasting recession as observed in other European countries. AKEL was ready to negotiate with the Troika in order to preserve the economic affluence of the country but they were not willing to compromise on their fundamental values (Fenwick, 2012). The Troika insisted on restructuring the economy by bringing some sensitive issues to the negotiating table. The Wage Indexation or Cost of Living Agreement (CoLA), the 13th month salary and the privatization of semi-private organizations were some of the controversial moves proposed by the Troika. AKEL opposed these measures and since there was no agreement on the issue, market distortions became a problem (Fenwick, 2012).

The salaries of government employees in Cyprus were the highest among the European countries (Πολεμιδιώτης and Χαρουτουνιάν, 2012, p. 318). Meanwhile, the number of staff employed in the public sector followed an increasing trend for decades (Πολεμιδιώτης and Χαρουτουνιάν, 2012, p. 332). Despite the bad economic situation of the island, the previous government continued to hire new civil servants (Cyprus News Report, 2011). Since the foundation of the Republic of Cyprus in 1960, the structure of the public service was based on clientelism (Faustmann, 2010). Each party that got in power helped their supporters by providing jobs in the public sector. They were abusing public office in order to secure votes in the next elections. The advantages that this corrupt public sector is offering, such as high wages and few working hours, contributed to the establishment of a system that costs too much but is neither efficient nor effective (Panayotou, 2013).

During the end of 2012, there was hard bargaining between the Troika and the Cypriot government. The Cypriot government had little leeway in discussions with the Troika. The European Commission, the European Central Bank and the IMF were ready to provide loan for the island to recapitalize its banks. However, providing this loan was not without conditions. The Troika reported that structural changes and budget cuts should be implemented before it can provide any loan to the island. In late 2012, the Cypriot government and Troika were close to signing a Memorandum agreement. However, they could not finalize this agreement as they were waiting for the report of an independent agency (PIMCO) which would clarify the exact amount needed for the recapitalization of the banks in Cyprus. The negotiations with the Troika created a great wave of reactions among trade unions which have for a long time been a close ally of AKEL. These unions argued that the achievements which were won with great sacrifices by the workers and the labor movement could go in wane as a result of the demands of the Troika (The Revolutionary Communist Manifesto, 2013). Despite the initial opposition from AKEL, the House of Representatives proceeded to implement some measures demanded by the Troika. The House of Representatives passed 28 bills that cut the salaries and pensions (Demetriades, 2013). The government was blamed for delaying further painful but necessary reforms demanded by the Troika. AKEL was nervous about implementing further austerity measures that would be contradictory with its left-wing ideology.

In times of economic crisis, there are opportunities to implement structural reforms that can help the economy to emerge from recession. However, as we have seen with previous cases in Southern Europe, the necessary reforms have a political cost. Structural changes can lead to public outcry and put pressure on the political party in power. Reluctance of AKEL to implement structural reforms may have contributed to the country’s decline toward bankruptcy. Toward the end of its incumbency, there has been a blame game between AKEL and the opposition in regard to the handling of the economy. The reality is that all political parties had their share of responsibility because none of them wanted to bear the political cost of reforms and did not implement them when they were in power. The irresponsible actions of banks in conjunction with clientelism have led the Cypriot economy to the brink of collapse. At the same time, there is no doubt that there was flawed administration by AKEL.

Amidst these economic developments, AKEL had to face the electoral challenge on 17 February 2013, 5 years after it took office. The result for AKEL was devastating. Compared with the 33.29 per cent of the votes secured by AKEL’s candidate Demetris Christofias in the first round, Stavros Malas, who was backed by AKEL, could only get 26.91 per cent of the vote. That was 6.38 per cent less than what Christofias received 5 years ago. In the second round which took place on 24 February 2013, Nikos Anastasiades swept to victory with 57.48 per cent of the votes. Hence, AKEL was ousted by securing only 42.52 per cent of the votes in the second round. This was 10.85 per cent less than what the party received in February 2008. Could this defeat be caused by the deteriorating economy? Even though it might not be possible to exactly know the real determinants of vote choice due to lack of data, we can examine vote intentions by using the European Elections Study (2009) data. Therefore, our research question is as follows; how did the deteriorating economy influence the vote intention for AKEL in February 2013 election? We present the economic voting theory and the results of our statistical analysis in the next part.

Economic Voting

Cyprus problem is perceived by many Cypriots to be the most important issue when it comes to supporting political parties. Annan Plan referendum in 2004 which aimed to reunify the country by including Turkish Cypriots in governance was rejected by the Greek Cypriots. Political campaigns in the Republic of Cyprus have especially revolved around the positions on the Cyprus issue since then (Ker-Lindsay, 2006; Christophorou, 2007, 2008; pp. 229–230; Charalambous, 2009, p. 99). Other than this issue, socio-psychological issues could be cited as a motivation for vote choice in the Republic of Cyprus. In Cyprus, nearly everything is politicized (Charalambous, 2007, p. 444; Dunphy and Bale, 2007, p. 300; Vasilara and Piaton, 2007, p. 117). Politics penetrate into every aspect of the society including sports clubs and restaurants. The majority of the people have a strong sense of belonging to the left or right with very low volatility, strong party discipline and high numbers of party membership (Charalambous, 2003, p. 112; Charalambous, 2007, p. 443; Bosco and Morlino, 2006; Caramani, 2006; Christophorou, 2006, p. 517 and 527; Dunphy and Bale, 2007, p. 302). It is no wonder that the number of people who identifies themselves with political parties is very high and much higher than the EU average as shown in all the surveys to date. Most Greek Cypriots are partisans and partisanship might be one of the strongest determinants of vote choice in the Republic of Cyprus. The role of economic evaluations, however, is not cited as a factor for party choice. This can be due to the focus on the politicization of the Cyprus problem and/or the parties’ strong psychological ties with the voters but also due to the absence of economic crises.

We acknowledge the importance of the Cyprus problem and socio-psychological processes as determinants of vote choice. However, we also argue that the Greek Cypriots are able to make judgments about the state of the economy and that these judgments influence the way they vote in the elections. The idea behind the economic voting hypothesis is simple. If the economy does well, the incumbent party benefits from this in the next elections, if not it suffers in the next elections (Fiorina, 1981; Lewis-Beck, 1990; Norporth, 1996). The vast economic voting literature clearly shows that voters are more inclined to make their choice based on the economic performance of the country (sociotropic voting) rather than the financial situation of their household (egocentric voting) (Kinder and Kiewiet, 1981; Kiewiet, 1983, p. 99; Lewis-Beck, 1990, p. 57). We expect to see the Greek Cypriots who perceive the national economy to be doing worse under AKEL’s leader Christofias’ incumbency to be less likely to express a vote intention for AKEL in the next election.

Hypothesis:

-

Greek Cypriots who perceive the national economy to be doing worse under AKEL’s leader Christofias’s incumbency are less likely to express a vote intention for AKEL in the next election.

We are aware of the recent debate between those who argue whether economic perceptions are endogenous or exogenous (Evans and Andersen, 2006; van der Brug et al, 2007; Lewis‐Beck et al, 2008; Evans and Pickup, 2010; Nadeau et al, 2012; Hansford and Gomez, 2013). Conflicting results probably suggest that simultaneous causality is in place. At this initial stage of studying economic voting in Cyprus, we are unable to measure two-way causality as we believe that doing so obliges us to collect panel data. We should note that political behavior is a nascent topic in Cyprus and panel data or time-series data do not yet exist. European Elections Study is the only data set that allows us to measure economic voting and we tend to shy away from using imperfect instruments for two-stage regressions. Therefore, we should caution the reader that the magnitude of economic voting that is observed in this article may be inflated to a certain extent. By the period between 9 June to 6 July 2009 when the fieldwork of the European Elections Study (2009) took place, the Greek Cypriot voters had a chance to evaluate the competence of the party in dealing with the economy. This survey was conducted around 15–16 months after AKEL won the election and the survey includes a question which allows the measurement of voters’ evaluation of the current economic situation compared with 12 months ago, which is right after the party got into office. In contrast to the endogeneity issue, we expect the magnitude of economic voting in this article to be deflated compared with the February 2013 election. This is because the magnitude of economic voting increases during the times of crisis and the Cypriot economy was doing much worse in February 2013 (Singer, 2011b; Freire and Santana-Pereira, 2012; Nezi, 2012; Fraile and Lewis-Beck, 2014).

Retrospective sociotropic economic voting was measured on a five-point scale. Asked about the general economic situation in the Republic of Cyprus compared with 12 months ago, the respondents who thought it was ‘a lot worse’ are coded as 0, those who thought it was ‘a little worse’ are coded as 1, those who thought it ‘stayed the same’ are coded as 2, those who thought it was ‘a little better’ are coded as 3 and those who thought it was ‘a lot better’ are coded as 4. This study controls for class and religiosity as potential sociological determinants of vote for AKEL. As it is a left-wing party, we expect working class and non-religious people to be more likely to vote for AKEL. Social class variable consisting of five cohorts is recoded and introduced into the model as dummy variables keeping working class as the base. These dummy variables are ‘upper class’, ‘upper middle class’, ‘middle class’, and ‘lower middle class’. Religiosity is measured with an ordinal scale consisting of 11 cohorts. The respondents were asked about how religious they consider themselves as. The possible answers ranged from ‘not at all religious’ coded as 0 to ‘very religious’ coded as 10.

In the Republic of Cyprus, left–right cleavage implies distinct stance on education reform, the role of the church, attitude toward Europe and the Cyprus problem (Charalambous, 2009, p. 112). Ideology (left–right scale) provides us an important control variable taking into account the psychology of the voter as well as his/her stance on important issues. We should stress here that ideology in the Greek Cypriot context is intertwined with party identification. Pearson’s correlation between an 11-point left–right scale and vote intention for AKEL is −0.72. Although party identification could be used as a control in other contexts, it does not provide enough statistical independence from the vote choice in the Republic of Cyprus. Greek Cypriots almost never vote for any other party than the ones they identify themselves with. The correlation between identification with AKEL and the vote intention for AKEL is 0.90. Ideology is measured with an ordinal scale comprised of 11 cohorts. When asked to place themselves on a political left–right continuum, the respondents could choose from 0 which is ‘left’ to 10 which is ‘right’.

Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1 and Table 2 provides a correlation matrix. Table 3 reports the results from the logistic regression. The results show that the effect of retrospective sociotropic economic voting is significant at 99 per cent confidence level. The model can explain up to 70 per cent per cent of variance if we rely on the Nagelkerke’s R 2. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 1.61 times less likely for Greek Cypriot citizens as evaluation gets worse on the 5-point scale. This finding is significant at 99 per cent confidence level. For a better demonstration of the effect, we graphed the predicted probabilities with 95 per cent confidence intervals which can be seen in Figure 3. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 1.19 times more likely as the voters report being less religious on the 11-point scale. This finding is again significant at 99 per cent confidence level. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 5.88 times less likely for the voters who see themselves as upper class compared with the voters who see themselves as working class. This finding is significant at 90 per cent confidence level. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 3.13 times less likely for the voters who see themselves as upper middle class compared with the voters who see themselves as working class. This finding is significant at 95 per cent confidence level. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 1.54 times less likely for the voters who see themselves as middle class compared with the voters who see themselves as working class. This finding is significant at 90 per cent confidence level. The probability of intending to vote for AKEL does not significantly differ for the voters who see themselves as lower middle class and the voters who see themselves as working class. The odds of intending to vote for AKEL are 1.96 times more likely as the voters become more leftist on the 11-point scale. This finding is significant at 99 per cent confidence level.

Discussion and Conclusion

We argued that the Greek Cypriots are able to make judgments about the state of the economy and that these judgments influence the way they intend to vote in the elections. If the economy does well, the incumbent government benefits from this in the next elections, if not it suffers in the next elections. We provided evidence for this argument by relying on public opinion data. On the basis of this result and the painstaking economic developments when former President Christofias was in office, we may argue that the substantial amount of votes lost by AKEL might be due to the deteriorating economic situation since it took office in February 2008.

At the time of writing, the Republic of Cyprus is going through one of the toughest economic crisis in its history. After the negotiations between the current right-wing President Nikos Anastasiades and the Troika, the Cypriot government agreed to implement a ‘haircut’ on deposits above €100 000 in The Popular Bank and the Bank of Cyprus. The exact amount of the ‘haircut’ for the deposits above €100 000 was expected to be 47.5 per cent (Cyprus Mail, 2013a). In return, the island secured €10 billion from the EU and the IMF. This deal was struck after the rejection of the first deal by the Cypriot parliament. The first deal was a plan to implement a haircut of 12.5 per cent of deposits above €100 000 and 6.7 per cent below €100 000. The combination of €10 billion and the money to be raised from the ‘haircut’ was thought to be sufficient to cover what the island needed in order to not go bankrupt. However, the most recent reports suggest that the figure needed to prevent the bankruptcy of the Republic of Cyprus was underestimated. The real figure that is needed is now agreed to be €23 billion (BBC News, 2013).

Public debt will be around 130 per cent of the country’s total GDP as a result of the loan the island will receive. The government may have to raise more money on its own by increasing the percentage of the ‘haircut’ that will be implemented as well as putting into action different measures aiming to restart the economy. Restarting the economy is needed not only for raising money in the short-term but to ensure the ability of the island to pay back its debt in the long-term. Such measures include raising the corporate tax by 2.5–12.5 per cent, allowing casinos to operate in the Republic of Cyprus in order to prevent Greek Cypriots from gambling in the northern part of the island that is not under the effective control of the Republic of Cyprus, attracting tourists to the island, privatization of semi-private organizations such as the Cyprus Electricity Authority (AIK) and Cyprus Telecommunications Authority (CYTA), and building of a liquefied natural gas station for extracting gas reserves that were found around the island. The benefits that will be raised from the gas reserves are the greatest hope the island has (Fenwick, 2013). Most analysts are wary of the Republic of Cyprus’s ability to raise the amount needed and to pay back its debt without further aid from the Troika (Cyprus Mail, 2013b).

We can argue that the magnitude of economic voting in the Republic of Cyprus is likely to increase substantively after the catastrophic crisis in early 2013. The crisis will not be the only factor in influencing the magnitude of economic voting. Kayser and Wlezien (2011) found that as party identification decreases, the magnitude of economic voting increases. Party identification is decreasing rapidly in the Republic of Cyprus. It was 96.17 per cent in 2004, 71.27 per cent in 2006, 68.24 per cent in 2008 and 56.49 per cent in 2010 according to International Social Survey (ISSP Research Group, 2012) and European Social Survey (2006, 2008, 2010) data. This may combine with the current economic crisis to produce a sharp increase in the magnitude of the impact of economic perceptions on the vote choice.

References

Agence France-Presse (2013.) Cyprus launches criminal probe into banking crisis, 5 July, http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/afp/130705/cyprus-launches-criminal-probe-banking-crisis, accessed 15 July 2013.

Anderson, C.J. and Hecht, J.D. (2012.) Voting when the economy goes bad, everyone is in charge. and no one is to blame: The case of the 2009 German election. Electoral Studies 31(1): 5–19.

BBC News (2013.) Cost of Cyprus bailout ‘rises to 23 bn Euros’, 11 April, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-22106194, accessed 15 July 2013.

Bellucci, P., Costa Lobo, M. and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (2012.) Economic crisis and elections: The European periphery. Electoral Studies 31(3): 469–471.

Bosco, A. and Morlino, L. (2006) What changes in South European parties? A comparative introduction. South European Society and Politics 11(3): 331–358.

Caramani, D. (2006) Is there a European electorate and what does it look like? Evidence from electoral volatility measures, 1976–2004. West European Politics 29(1): 1–27.

Charalambous, G. (2003) A European course with a communist party: The presidential election in the republic of Cyprus, February 2003. South European Society and Politics 8(3): 94–118.

Charalambous, G. (2007) The strongest communists in Europe: Accounting for AKEL’s electoral success. Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 23(3): 425–456.

Charalambous, G. (2009) The February 2008 presidential election in the republic of Cyprus: The context, dynamic and outcome in perspective. The Cyprus Review 21(1): 97–122.

Christophorou, C. (2006) Party change and development in Cyprus (1995–2005). South European Society and Politics 11(3–4): 513–542.

Christophorou, C. (2007) An old cleavage causes new divisions: Parliamentary elections in the republic of Cyprus, 21 May 2006. South European Society and Politics 12(1): 111–128.

Christophorou, C. (2008) A new communist surprise – What’s next? Presidential elections in the republic of Cyprus, February 2008. South European Society and Politics 13(2): 217–235.

Christophorou, C. (2012) Disengaging citizens: Parliamentary elections in the Republic of Cyprus, 22 May 2011. South European Society and Politics 17(2): 295–307.

Cyprus Mail (2013a) Our view: It will take much more than positive statements to restore confidence, 31 July, http://cyprus-mail.com/2013/07/31/our-view-it-will-take-much-more-than-positive-statements-to-restore-confidence/, accessed 31 July 2013.

Cyprus Mail (2013b) Risks of a new Cyprus default remains elevated, says Moody’s, 13 July, http://cyprus-mail.com/2013/07/13/risk-of-a-new-cyprus-default-remains-elevated-says-moodys/, accessed 15 July 2013.

Cyprus News Report (2011) Number of public employees rises 1.9% in 2010, 29 April, http://www.cyprusnewsreport.com/?q=node/4030, accessed 05 July 2013.

Demetriades, P. (2013) Cyprus: Not blameless but misunderstood. Financial Times 22 June, http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a7a24b3e-64b6-11e2-934b00144feab49a.html#axzz2LHs2Jz9h, accessed 5 July 2013.

Dunphy, R. and Bale, T. (2007) Red flag still flying? Explaining AKEL – Cyprus’ communist anomaly. Party Politics 13(3): 287–304.

EES (2009) European parliament election study 2009, Voter study, advance release, 7/4/2010, http://www.piredeu.eu.

ESS Round 3: European Social Survey Round 3 Data (2006) Data file edition 3.4, Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data, accessed 15 July 2013.

ESS Round 4: European Social Survey Round 4 Data (2008) Data file edition 4.1, Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data, accessed 15 July 2013.

ESS Round 5: European Social Survey Round 5 Data (2010) Data file edition 3.0, Norwegian Social Science Data Services, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data, accessed 15 July 2013.

European Commission (2013) European Commission Economic and Financial Affairs, http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/assistance_eu_ms/cyprus/index_en.htm, accessed 15 July 2013.

EUROSTAT (2013a) Public debt, http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/table.do?tab=table&init=1&language=en&pcode=tsdde410&plugin=1, accessed 20 April 2013.

EUROSTAT (2013b) Unemployment 1. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_PUBLIC/3-01072013-BP/EN/3-01072013-BP-EN.PDF, accessed 3 July 2013.

EUROSTAT (2013c) Unemplyment 2. http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=z8o7pt6rd5uqa6_#!ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=unemployment_rate&fdim_y=seasonality:sa&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=country_group&idim=country:cy&idim=country_group:noneu&ifdim=country_group&hl=en_US&dl=en_US&ind=false, accessed 20 April 2013.

Evans, G. and Andersen, R. (2006) The political conditioning of economic perceptions. Journal of Politics 68(1): 194–207.

Evans, G. and Pickup, M. (2010) Reversing the causal arrow: The political conditioning of economic perceptions in the 2000–2004 US presidential election cycle. Journal of Politics 72(4): 1236–1251.

Famagusta Gazette (2013a) Central bank governor says Cyprus will receive one of the largest bank bailouts ever, http://famagusta-gazette.com/central-bank-governor-says-cyprus-will-receive-one-of-the-largest-bank-bail-p17474-69.htm, accessed 20 April 2013.

Famagusta Gazette (2013b) Cyprus memorandum of understanding on specific economic policy conditionality, http://famagusta-gazette.com/full-text-cyprus-memorandum-of-understanding-on-specific-economic-policy-c-p18824-69.htm, accessed 15 July 2013.

Faustmann, H. (2010) Rousfetti and political patronage in the republic of Cyprus. The Cyprus Review 22(2): 269–289.

Fenwick, S. (2012) Troika talks: Still no agreement on CoLA, bank recapitalisation. Cyprus News Report, 11 February, http://www.cyprusnewsreport.com/?q=node/6294, accessed 15 July 2013.

Fenwick, S. (2013) President Anastasiades anounces measures to boost economy. Cyprus News Report, 20 April, http://www.cyprusnewsreport.com/?q=node/6652, accessed 15 July 2013.

Fiorina, M.P. (1981) Retrospective Voting in American Elections. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fraile, M. and Lewis-Beck, M.S. (2014) Economic voting instability: Endogeneity or restricted variance? Spanish panel evidence from 2008 to 2011. European Journal of Political Research 53(1): 160–179.

Freire, A. and Santana-Pereira, J. (2012) Economic voting in Portugal, 2002–2009. Electoral Studies 31(3): 506–512.

Hansford, T. and Gomez, B. (2013) Reevaluating the Sociotropic Economic Voting Hypothesis. Mimeograph, Universtiy of California, Merced.

Howarth, N. (2012) Standard & Poor’s dowgrades Cyprus to junk status. Cyprus Property News, 14 January, http://www.news.cyprus-property-buyers.com/2012/01/14/standard-poors-downgrades-cyprus-to-junk-status/id=0010359, accessed 11 July 2013.

Hufftington Post (2012) Moody’s downgrades Cyprus credit rating to junk on Greek exposure, 13 March, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/13/moodys-downgrades-cyprus-credit-rating-greek-exposure_n_1341230.html, accessed 15 July 2013.

ISSP Research Group (2012) International Social Survey Programme: Citizenship – ISSP 2004. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA3950 Data file Version 1.3.0, doi:10.4232/1.11372.

Kanol, D. (2013) To vote or not to vote: Declining voter turnout in the republic of Cyprus. The Cyprus Review 25(2): 59–72.

Katsourides, Y. (2013) Determinants of right reappearance in Cyprus: The national popular front (ELAM), golden Dawn’s sister party. South European Society and Politics 18(4): 567–589.

Kayser, M.A. and Wlezien, C. (2011) Performance pressure: Patterns of partisanship and the economic vote. European Journal of Political Research 50(3): 365–394.

Ker-Lindsay, J. (2006) A second refererandum: The May 2006 parliamentary elections in Cyprus. Mediterranean Politics 11(3): 441–446.

Kiewiet, D.R. (1983) Macroeconomics & Micropolitics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D.R. and Kiewiet, D.R. (1981) Sociotropic politics: The American case. British Journal of Political Science 11(2): 129–161.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. (1990) Economics and Elections. The Major Western Democracies. MI: University of Michigan Press.

Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Nadeau, R. (2012) Pigs or not? Economic voting in Southern Europe. Electoral Studies 31(3): 472–477.

Lewis‐Beck, M.S., Nadeau, R. and Elias, A. (2008) Economics, party, and the vote: Causality issues and panel data. American Journal of Political Science 52(1): 84–95.

Marsh, M. and Mikhaylov, S. (2012) Economic voting in a crisis: The Irish election of 2011. Electoral Studies 31(3): 478–484.

Nadeau, R., Lewis-Beck, M.S. and Belanger, E. (2012) Economics and elections revisited. Comparative Political Studies 46(5): 551–573.

Nezi, R. (2012) Economic voting under the economic crisis: Evidence from Greece. Electoral Studies 31(3): 498–505.

Nicolaides, P. (2012) The president and his banker. PSEKA International Coordinating Community ‘Justice for Cyprus’, 5 June, http://news.pseka.net/index.php?module=article&id=12415, accessed 15 July 2013.

Norporth, H. (1996) The economy. In: L. LeDuc, R. Niemi and P. Norris (eds.) Comparing Democracies: Elections and Voting in Global Perspective. CA: Sage Publications, pp. 319–342.

Panayotou, T. (2013) Eleven lessons from Cyprus’ bitter experience. Cyprus Mail, 30 June, http://cyprus-mail.com/2013/06/30/eleven-lessons-from-cyprus-bitter-experience/, accessed 15 July 2013.

Πολεμιδιώτης, Μ and Χαρουτουνιάν, Σ (2012) Δημόσια οικονομικά: προκλήσεις και προοπτικές. In: Α Ορφανίδης and Γ Συρίχας (eds.) Κυπριακή Οικονομία: Ανασκόπηση, Προοπτικές, Προκλήσεις, Κεντρική Τράπεζα Κύπρου. Nicosia, Cyprus: Κεντρική Τράπεζα της Κύπρου, pp. 303–356.

Singer, M.M. (2011a) Who says ‘It’s the economy’? Cross-national and cross-individual variation in the salience of economic performance. Comparative Political Studies 44(3): 284–312.

Singer, M. (2011b) When do voters actually think ‘it’s the economy’? Evidence from the 2008 presidential campaign. Electoral Studies 30(4): 621–632.

Tanas, O. and Arkhipov, I. (2013) Russia rejects Cyprus financial rescue bid as deadline looms. Bloomberg Businessweek, 22 March, http://www.businessweek.com/news/2013-03-22/cyprus-s-sarris-to-leave-moscow-without-russian-financial-help, accessed 15 July 2013.

Theodolou, M. (2011) Inquiry blames ‘carelesness’ of Cyprus PM for munitions explosion that killed 13, 4 October, http://www.thenational.ae/news/world/europe/inquiry-blames-carelessness-of-cyprus-pm-for-munitions-explosion-that-killed-13, accessed 14 July 2013.

The Revolutionary Communist Manifesto (RCIP) (2013) Cyprus: General strike against EU Troika diktat and austerity program!, 28 April, http://www.thecommunists.net/worldwide/europe/cyprus-general-strike-against-eu-troika/, accessed 15 July 2013.

USA Today (2012) Fitch downgrades Cyprus credit rating to junk, 25 June, http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/world/story/2012-06-25/cyprus-credit-down-to-junk/55804356/1, accessed 12 July 2013.

van der Brug, W., van der Eijk, C. and Franklin, M.N. (2007) The Economy and the Vote: Economic Conditions and Elections in Fifteen Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vasilara, M. and Piaton, G. (2007) The role of civil society in Cyprus. The Cyprus Review 19(2): 107–121.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanol, D., Pirishis, G. The role of voters’ economic evaluations in February 2013 presidential elections in the Republic of Cyprus. Comp Eur Polit 15, 1016–1029 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2016.2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2016.2