Key Points

-

Suggests that patient reported outcome and experience measures can provide useful information to providers to improve both the quality of care delivered and the overall patient experience.

-

Highlights that questionnaires require careful design to ensure that relevant data is captured and that it is easy to interpret. They should be easy and quick to complete to avoid 'feedback fatigue'.

-

Proposes revised and improved questionnaires for oral surgery that incorporate the validated NHS Friends and Family Test.

Abstract

Introduction With the expansion of oral surgery services into the primary care sector there is a need to monitor the quality of the care provided. The Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine proposed a set of questions to be used as patient related experience and outcome measures (PREMs and PROMs).

Aim The British Association of Oral Surgeons (BAOS) primary care group (which includes the authors) were tasked by the Chief Dental Officer for England to test the suitability of these PREMs and PROMs.

Method The questions as published in the commissioning guide were piloted in primary care oral surgery practices and patient feedback was sought. The authors then proposed and implemented an amended series of questions that they felt would be more practical as generic templates for oral surgery services.

Results Our data demonstrates that the revised questions have produced data that is easy to interpret and attracted a greater number of feedback comments from patients.

Discussion and conclusion The revised questionnaires incorporate the NHS Friends and Family Test as the collection of this data is normally a contractual requirement for providers of NHS services. They also use questions from other validated healthcare satisfaction survey tools. The use of Likert scales provides a richer data set which makes the interpretation of data easier and highlights areas for improvement. It is important to note that the data provided by PREMs and PROMs is subject to a number of biases and should be used for local quality improvement and longitudinal analysis of outcome data rather than comparison between providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Primary care oral surgery services (PCOS) expanded following the Medical Education England Review of Oral Surgery Services and Training in 2010. This review concluded that 'there is considerable support for the expansion and extension of oral surgery services in the primary care setting to support local delivery of services'.1

This expansion in the number of providers means that robust methods for quality assurance are essential to ensure optimal patient care. The Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine2 (published in 2015) provides a framework for commissioning these services in a consistent and coherent way.

A section of this document is concerned with quality and outcome key assessment areas, two of which are patient reported experience measures (PREMs) and patient reported outcome measures (PROMs). The document recommended a standard set of PREMs and PROMs for oral surgery practice which will be used as part of a broad range of performance metrics for quality assurance and contract management. Whilst PREMs focus on the humanity of care, such as involvement in decision making and being treated with kindness and compassion, PROMs seek to measure functional status, health-related quality of life and patients' views of their symptoms. In England, they were first used nationwide to measure outcomes of mastectomy and breast reconstruction but have since been introduced for many elective surgical procedures including hip and knee replacements, groin hernia repair and varicose vein surgery.3 The use of these measures to compare the performance of different providers has been controversial given potential bias from collection format, case-mix, late or non-responders, socio-economic deprivation and ethnicity.4,5

The British Association of Oral Surgeons (BAOS) was tasked by the Chief Dental Officer for England to look at these generic PREMs and PROMs with a view to ascertaining their fitness for purpose. The BAOS primary care group (which includes the authors) planned to evaluate these in three different primary care practices. A second trial was then carried out with a set of amended PREMs and PROMs (based on the results of the first cycle) in an effort to generate generic, useful templates fit for oral surgery practice.

Materials and methods

There were two rounds of data collection, the first with the questionnaire as described in the commissioning guide2 and the second with modifications agreed by the authors. Patients were asked to complete the PREMs form prior to departure from the practices. Patients having sedation were included although they were only presented with the form once fitness for discharge was established. In the first round the requirement for two of the practices to collect NHS Friends and Family Test (NHS FFT) data meant that patients had to fill in two questionnaires. In the second round the incorporation of the NHS FFT questions into the PREMs form meant that only one form was necessary.

PROMs were collected by telephoning patients and the process differed between the two rounds. In the first round, all patients were contacted within 24 hours of the procedure and in the event of the patient being unavailable, a second and final contact was attempted the following weekday. In the second round patients having simple, non-surgical extractions where the surgeon had no concerns about healing and recovery were not contacted. The window for the first attempt at contacting the patient was also explicitly extended to up to 72 hours after the procedure.

Practices entered data individually into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets which were then combined. Each practice was identified by a code. Feedback from each round of data collection was sought from surgeons and the nurses carrying out the PROMs telephone calls to identify any questions that could be improved upon or any difficulties with recording data accurately.

Results

PREMs

Round 1 data

The first round used the exact PREMs questions found in the commissioning guide.2 These questions are shown in Figure 1.

The data demonstrated an overwhelmingly positive view, with four out of six questions receiving unanimous approval from patients (Table 1). All but one patient responded positively to question two on the understanding of the risks and benefits of surgery. The final question (relating to explanation of medication side effects) was the only one that demonstrated any disagreement, with one negative response and nine patients saying they weren't sure. Whilst all the surgeons routinely recommended suitable analgesics, none routinely dispensed them to patients and this may explain the response, especially for patients already taking prescribed analgesia for other conditions.

In this first round, 102 out of 219 patients made a written comment in the space provided.

Modifications

There was general agreement that a paper questionnaire immediately following treatment was an appropriate method for collecting this data and the administration of the PREMs was straightforward. Whilst the data demonstrates an encouragingly high performance from the practices involved, this also demonstrates the limitations of an agree/disagree question design in failing to uncover degrees of opinion. Given the enormous potential for bias in surveys of this type, the data provided is likely to be wholly unsuitable for the purposes of comparing providers as the differences will not approach significance.

Two of the practices were required to collect NHS Friends and Family Test (FFT) data and used locally adapted forms of this. As this was a contractual requirement the FFT continued in tandem with the PREMs form. This duplication increases the burden on patients and may contribute to non-response bias for both the FFT and the PREMs.

The final questionnaire (Fig. 2) combines the FFT with questions used in the National Outpatient Survey and in primary care patient satisfaction surveys such as those provided by the survey company IWantGreatCare. These validated questionnaires have been designed to be easy to understand and complete. They cover similar domains of experience as in the round 1 questionnaire but the questions are broader in scope. No question is included that specifically addresses medication side effects, but there is a question relating to the receipt of timely information about care and treatment. The use of a Likert scale provides a much richer data set which then makes identification of areas for improvement far easier.

Round 2 data

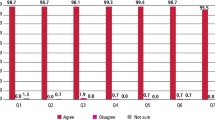

Although the experience measures once again showed very high satisfaction (Table 2), there was greater heterogeneity in the data as no single question received unanimous responses. 157 out of 202 (78%) patients made comments, which was a considerable improvement on the first round (47%) and may be a result of having a single form to complete. A selection of these comments are shown in Box 1.

PROMs

Round 1

The questions used are shown in Table 3. The first round was completed following the instruction that phone calls should be completed within 24 hours wherever possible. For treatment taking place on a Friday calls were made the next working day, which was normally Monday. Only 106 out of the 219 patients could be contacted in the two prescribed call attempts (48.4%). The data is shown in Table 4.

The feedback from this round demonstrated some significant problems with the structure of the questionnaire. The first question asks if the patient needed to seek any advice or assistance hours or days after the procedure. Given the intention that only 24 hours had elapsed, the reference to days is clearly inappropriate; nor is it obvious why the question does not ask about presence of a complication, rather than whether the patient has needed advice or assistance with it. Thirteen patients (12.2%) reported complications. The complications identified were within the expected ranges within the commissioning guide2 and the two patients reporting altered sensation to the lower lip following surgery were contacted again within a week and full resolution was reported.

The question regarding the need for additional surgery subsequent to the original procedure also seems inappropriate given the intention that the survey be carried out within 24 hours. No patients requiring emergency surgery at another unit were identified in this sample. The final question regarding the time taken to achieve restoration of normal activities or appearance (a mean of 1.2 days across all patients) is also problematic. It is unclear how patients who are recovering perfectly well but choosing to eat on the other side of their mouth should respond to this question or whether there is an expectation that such a patient should be contacted again to ensure restoration of normal function as suggested in the commissioning guide.2

Modifications

Whilst calls within 24 hours were considered useful for identifying early complications such as uncontrolled pain, bleeding or nerve injury, it is likely to be too soon to identify common late complications such as dry socket, infection, unintentional retention of tooth fragments or bony sequestra. Rather than a blanket requirement for a 24 hour call, the authors felt that a window of 24-72 hours was most appropriate and that this could be tailored for each individual patient. For example, patients on anticoagulants or those having high-risk mandibular third molars removed may benefit most from early contact whilst an immuno-compromised patient having a simple extraction may be more usefully contacted at 72 hours, with further home checks if a problem is reported.

The questions have been simplified to identify any immediate problems and establish whether advice or emergency treatment has been sought elsewhere.

The proposed questionnaire is shown in Table 5 and it was decided that telephone calls would only be carried out for patients having surgical procedures or if it was requested by the surgeon. This reflected the case-specific risk of complications and the comments received from patients in round one, many of whom felt the need for a home check telephone call after a straightforward procedure was unnecessary.

Round 2 data

In this round contact was attempted with 128 patients out of the 220 treated and the data is shown in Table 6. The response rate was 44.5% after two call attempts, a slight reduction on the first round. Out of the 71 patients who answered questions, 11 reported complications (15.5%). It is reassuring that the proportion of patients reporting complications increased slightly over the first round, suggesting that the concentration of resources on more complex or complication-prone cases has had little effect on the overall number of adverse outcomes reported in these cohorts. The comments for question 3 show that the majority of patients were seen in the specialist oral surgery practice but four patients had interventions from their own dentist or GP (in one case this was by prior arrangement due to long travel distances).

Discussion and conclusion

One of the principles that guided the development of the NHS FFT was that it should be quick and easy to complete in order to maximise the response rate. This should apply equally to PROMs and PREMs where much as clinicians may wish for very detailed data, the high level of response bias for a longer questionnaire may render it almost meaningless.

We proposed simplified questionnaires to maximise the response rate, minimise inconvenience to patients and provide high quality data so that individual practices have detailed information to support quality improvement projects. Our data demonstrates that the revised questions have produced data that is easy to interpret and have attracted a greater number of feedback comments from patients. We recognise that oral medicine providers may benefit from a modified version of these questionnaires. All the practices participating in this evaluation reported that the collection and collation of this data was time consuming and resource intensive and these additional administrative costs must be reflected in the procedural tariffs.

The review of the FFT4 repeatedly stresses that the test as currently administered is subject to a number of biases and consequently is of questionable validity. This means that the data are not fully comparable and unsuitable for performance management purposes. The same limitations would apply to PROMs and PREMs and their value may be greatest in driving local quality improvement and longitudinal analysis of outcome data rather than as a comparison between providers.

References

Medical Education England. Review of Oral Surgery Services and Training. 2010. Available at http://www.baos.org.uk/resources/MEEOSreview.pdf (accessed June 2017).

NHS England. Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine. 2015. Available at http://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-oral.pdf (accessed June 2017).

Black N . Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ 2013; 346: f167.

Hutchings A, Grosse Frie K, Neuburger J, van der Meulen J, Black N . Late response to patient-reported outcome questionnaires after surgery was associated with worse outcome. J Clin Epidemiol 2013; 66: 218–225.

NHS England. Review of the Friends and Family Test. 2014. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fft-rev1.pdf (accessed June 2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the nursing staff in the oral surgery practices for their diligence and hard work in collecting and collating this data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gerrard, G., Jones, R. & Hierons, R. How did we do? An investigation into the suitability of patient questionnaires (PREMs and PROMs) in three primary care oral surgery practices. Br Dent J 223, 27–32 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.582

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2017.582

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Effectiveness of registered nurses on patient outcomes in primary care: a systematic review

BMC Health Services Research (2022)

-

Patient-reported experience and outcome measures in oral surgery: a dental hospital experience

British Dental Journal (2020)