Abstract

Background/objectives

Hospital malnutrition is a common problem worldwide. This study aims to assess the validity of widely used nutritional screening tools for hospitalized adults in acute care settings in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Subjects/methods

Participants in this study were 693 adult patients from six general public hospitals, in a multi-center survey undertaken in April and May, 2016. The criterion validity of the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST), Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), Nutrition Risk Screening (NRS-2002) and Mini Nutrition Assessment—Short Form (MNA-SF), modified MST (MST combined with low BMI), and BMI as independent tools were assessed using Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) or low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) as the reference method. Area under curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated using the ROC curve method to determine the validity of screening tools.

Results

NRS-2002, modified MST (MST + low BMI), MUST, and BMI at 21 kg/m2 showed moderate/fair validity compared to the reference method (SGA or BMI). MST alone and MNA-SF showed poor validity due to low sensitivity (41.8 and 35.0% for MST and MNA-SF, respectively).

Conclusions

Based on specificity and sensitivity, the first choice for the most appropriate screening tool for use in Vietnam is the NRS-2002, following by the MST + BMI, MUST, and BMI alone at the cut-off value of 21 kg/m2. Further investigation on the feasibility and acceptability are required to determine the most appropriate screening tools for use within the Vietnamese context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition in acute care settings is a common problem worldwide with prevalence varies from 20.0 to 50.0% [1]. According to a survey in Ho Chi Minh city (HCMC) Vietnam, at least one in three adults (34.1%) in acute care settings were malnourished, representing a significant health issue [2]. Many studies have confirmed the severe impact of malnutrition during hospitalization on morbidity and mortality [3, 4].

In order to identify, prevent, and manage malnutrition, all patients should be screened for risk of malnutrition as soon as possible on or after hospital admission. Nutrition screening should be conducted using validated screening tools ensuring that it is simple enough to enable it to be used by general trained non-nutrition hospital staff [5]. In Western countries, there are a variety of validated screening tools recommended for use in acute care settings such as the: Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST) [6]; Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) [7]; Mini Nutrition Assessment Short-Form (MNA-SF) [8]; and Nutrition Risk Screening 2002 (NRS-2002) [9]. However, most of these validated screening tools have been developed for Caucasian populations, such as Australia (MST), United Kingdom (MUST), European countries (NRS-2002), and the United States (MNA-SF). In Asia, NRS-2002 and MNA-SF have been validated in one study in Singapore but only within elderly populations[10]. For adult populations in Asian countries, although international screening tools have been used [11], studies on their validity are limited. In Vietnam no malnutrition screening tools have been developed, validated, or recommended for use. With differences in body composition [12], cultural context, variability in accessing hospital resources and differences in population-wide nutrition issues, the validity of international screening tools in the Vietnamese hospital context are unknown. The validity of a screening tool can also be influenced by other local factors, such as a higher prevalence of underweight before hospital admission; disease patterns and socio-economic status [2].

In order to improve the nutritional status of patients in hospitals, health authorities in HCMC need to know the most valid screening tools for identifying risk of malnutrition in hospitalized patients that are relevant to this population for development of policies related not only to screening for malnutrition but also to the nutritional assessment and treatment of hospitalized patients in HCMC.

Materials and methods

Patients

Participants in this study were adult patients from six general public hospitals in HCMC who were a subsample of a multi-center survey on the prevalence and associated risk factors of hospital malnutrition undertaken in April and May 2016 [2]. General hospitals can be divided into three levels (one, two, or three), based on the technical qualifications of medical staff, specialities catered for, equipment and infrastructure, with Level on the highest. This survey used a stratified multi-stage cluster sampling strategy. First, general public hospitals in HCMC were divided into three strata: Level 1 general public hospitals, Level 2 general pubic hospitals, and Level 3 general public hospitals. Second, in each stratum, two hospitals were selected on a convenience basis that represented three geographic zones (urban, semi-urban, and rural) of the city. Third, in each of the selected hospitals, internal medicine and surgical wards were selected on a convenience basis to cover wards from different medical specialities. Finally, In each of the selected wards, the number of patients proportionate to the number of beds in that hospital strata were recruited. Participants were adult patients over 18 years old who presented at selected wards during the study period except those who were critically ill, palliative, pregnant, or unable to give informed consent. The invitation to participate, written information sheet and consent forms were given to all eligible patients one day prior to data collection.

Measurements

Body weight was measured using Tanita™ electronic scales to the nearest 100 g and body height was measured using a portable World Health Organization (WHO) recommended standard height scales to the nearest 0.1 cm. All measurements were taken using standard procedures according to WHO guidelines [13]. If height or weight were not measurable, participants were excluded from the analysis of this study.

Risk of malnutrition was measured using the MST [6], MUST [7], NRS-2002 [9], and MNA-SF [8]. These screening tools were selected because they were found to be validated to predict malnutrition in hospitalized patients in acute care settings [4, 14,15,16,17]. The parameters, as well as the cut-off values, to define risk of malnutrition for each of the screening tools are presented in Table 1. Questions that were duplicated across tools (BMI, weight loss, and poor dietary intake) were only asked once and then inferred in different tools to reduce the burden for participants.

The cross-cultural adaption process from Beaton et al. [18] which comprises six steps, including translation, synthesis, back translation, expert committee review, and committee appraisal, was used to translate all questions into Vietnamese for this study.

Data was collected by medical doctors, nurses, and bachelor of public health staff of the Nutrition Centre, HCMC Vietnam. Inter-rater reliability on the use of the screening tools among different research assistants was evaluated through a pilot on 30 patients in one hospital and all research assistants show consistent reliability (with interclass correlation coefficient = 0.72). SGA was assessed by the principal researcher, who is a medical doctor with clinical nutrition training employed by the Nutrition Centre HCMC. The principal researcher was trained and had experience in using SGA [19]. All screening tools were assessed in each participant by a single researcher.

Determination of malnutrition

Nutritional status of participants was measured using the assessment tool Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) [20]. SGA was used as the diagnostic tool as its parameters align with elements in diagnostic criteria from the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) [21]. In addition, according to the diagnostic criteria from the European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN), patients are diagnosed with malnutrition if they also have a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 [22]. Therefore, participants were defined as malnourished if they were classified as a “B” or “C” on SGA, or they had a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (SGA or BMI).

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using the statistical package STATA version 10.0 (2007, Stata corporation, TX, US) [23] and weighted for the strata and cluster sampling design. Sampling weights for the number of participants in each hospital were calculated to account for the difference in stratified cluster sampling design. The weights were calculated by using W1 × W2 where W1 is the weight of hospital in each hospital level stratum and W2 is the weight of patients in each selected hospital. W1 of each of hospital was calculated by using the total number of beds in that hospital divided to the average number of bed per hospital in that stratum. Similarly, the W2 of each of hospital ward was calculated by using the number of patients in that wards divided the average number of patients per wards in that hospital. Sampling weight process helps to provide more representative prevalence.

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, area under the ROC curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and percentage of correctly classified were calculated for each screening tool using SGA or BMI as reference standards.

AUC was utilized to determine the criterion validity of a screening tool, and to compare the two screening tools on the same subject [24]. The screening tools with the highest AUC, acceptable sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and percentage of correctly classified participants were considered as the most valid screening tools for use.

Regarding the validity rating, a screening tool was classified as “good” if both sensitivity and specificity were >80% or AUC was >0.8;”moderate/fair” if sensitivity or specificity are <80% but both were >50% or AUC was in the range of 0.6–0.8. The tool was classified as poor if sensitivity or specificity was <50%, or AUC was <0.6 [15].

Ethics

The protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Queensland University of Technology, Australia (Approval number 1500001156) and by Health Department HCMC Vietnam with approval number 2157/SYT-NVY.

Results

Among 887 participants in the survey, 194 (21.9%) participants, who had incomplete data or could not be measured weight and height directly (due to being bedridden, their medical condition or a severe decrease in functional capacity), were excluded from the analysis. The final sample size is 693 participants. In this survey, participants were more likely to be female (62.0%), and had lower socio-economic status compared to the general population, with 63.4% completing primary school or below, 24.4% belonging to households experiencing poverty or marginal poverty, and 56.3% not working in the last 6 months.

Characteristics related to malnutrition

Characteristics related to malnutrition among participants are presented in Table 2. The majority of participants had problems with acute weight loss and poor dietary intake. Almost half of participants had lost weight recently without trying (46.8%) and this mostly took place within the last month (46.3%). However, a majority of the weight losses were <5% of body weight (57.9%). Similarly, poor dietary intake was identified as an important issue with half of participants indicating a poor dietary intake (53.8%), and a majority of this decrease had occurred in the last week (44.9 %) with one-half (51.5%) consuming <50% of their normal requirement.

Gastrointestinal symptoms and neuropsychological problem were not a significant issue among the hospitalized adults sampled, and the prevalence of these issues was 12.3% and 9.7%, respectively.

Validity of screening tools

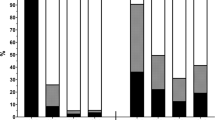

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV, and percent of correct classification for each nutrition screening tool, different cut-off values of BMI as an independent tool and the modified screening tools (MST + BMI) are presented in Table 3.

Among the available screening tools, MUST and NRS-2002 showed moderate/fair validity compared to the reference method (SGA or BMI) in this study. While MST and MNA-SF showed poor validity compared to the reference method because of the low sensitivity (with sensitivity of MST and MNA-SF 41.8% and 35.0%, respectively).

When MST was combined with low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2), findings indicated moderate/fair validity with significant improvements in AUC (0.74 vs. 0.62), sensitivity (66.8 vs. 41.8%), PPV (65.2 vs. 55.0%), NPV (82.1 vs. 72.7%), and percent of correctly classified (77.2 vs. 69.3%).

When BMI was examined as an independent tool, the AUC reached the highest level (0.73) at BMI 21 kg/m2. At this cut-off value, BMI also yielded the most optimal levels for sensitivity (64.6%), specificity (81.0%), PPV (64.3%), NPV (80.5%), and percentage of correctly classified (75.8%) compared to other cut-off levels.

Prevalence of risk of malnutrition

Prevalence of malnutrition (using SGA or BMI), risk of malnutrition using nutrition screening tools (MST, MUST, NRS-2002, and MNA-SF), and the risk of malnutrition using a modified tool (MST + BMI) and BMI alone (at the optimal cut-off of 21 kg/m2) are presented in Table 4. Prevalence of malnutrition risk varied significantly between different screening tools. The risk of malnutrition was highest with NRS-2002 (38.5%) and lowest with MNA-SF (18.1%). The prevalence of MST combined with BMI (36.0%) was closer to the prevalence from the reference (SGA or BMI) compared to prevalence from MST alone (27.2%). The prevalence BMI (at the cut-off of 21 kg/m2) (36.0%) was close to the prevalence of malnutrition using SGA or BMI as the reference method. The prevalence of malnutrition risk using a majority of the screening tools was lower than the prevalence of malnutrition (34.1%) except for the NRS-2002 (38.5%).

Discussion

The finding of moderate/fair validity of MUST and NRS-2002 in this study was comparable with other validity studies worldwide, where MUST and NRS-2002 were the most commonly tested tools, and showed fair to good validity in nutritional risk screening [14]. In Asia, this finding was also comparable to the finding from a validity study for an elderly Singaporean population in which NRS-2002 showed moderate/fair validity with AUC, sensitivity and specificity being 0.78, 69, and 79%, respectively [10]. Similarly, NRS-2002 also showed moderate/fair validity among cancer patients in Korea, with 62% sensitivity and 93% specificity [25].

In contrast, the results on the validity of the MST were different to those from the literature. While MST was also the most commonly tested tool and showed fair to good validity in a majority of validated studies internationally [14], it showed poor validity in this study. The poor validity of MST may be explained by the lack of BMI parameters in the tool compared to MUST and NRS-2002. This was a significant issue considering the high prevalence of low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) among Vietnamese hospitalized adults in this study (14%). This explanation was confirmed when the validity of MST improved significantly by combining it with BMI. The high prevalence of low BMI (<18.5 kg/m2) among Vietnamese hospitalized adults was also the explanation for the possibility of BMI as an independent screening tool in this study with moderate/fair validity.

MNA-SF showed poor validity in this study, with low sensitivity (35.0%). This may be due to the long reference duration (3 months) for the parameter on poor dietary intake. MNA-SF was not sensitive enough for this population where a majority of participants had short-term poor dietary intake (within 1 week). In addition, MNA-SF lacked sensitivity due to a majority of participants having a low prevalence of neuropsychological problems (9.7%). This was further explained by the exclusion of rehabilitation wards in this study.

When examining sensitivity, the sensitivity of NRS-2002 (74.6%), and MST + BMI (66.8%) were superior to the sensitivity of a BMI at 21 kg/m2 (64.6%) and MUST (63.4%). In ideal circumstances, higher sensitivity is preferred to enable the identification of malnourished patients as soon as possible for further assessment and intervention. This is especially important in acute care settings where patient length of stay routinely measured in days. Therefore, NRS-2002 and MST + BMI are more desirable compared to BMI alone and MUST.

When examining specificity, the specificity of MUST (85.2%) was better than the specificity of MST + BMI (82.0%), BMI at 21 kg/m2 (81.0%), and NRS-2002 (80.6%). In the context of limited resources, higher specificity is preferred because it will assist in reducing false positive cases, enabling resources to be mobilized to higher priority cases.

Regarding the structure of screening tools, NRS-2002 has been developed with two parts that serve as both screening and assessment. This means, it can be mobilized as an assessment tool in environments with limited resources to perform both screening and assessment. Regarding the determination of unintentional weight loss, MST is more practical than MUST as it provides direct weight loss categories rather than requiring calculation of percentage weight loss as seen in MUST.

Considering sensitivity, specificity and the structure of the screening tools, NRS-2002 would be the preferred choice following by MUST + BMI, with MUST and BMI alone at 21 kg/m2 in order of preference.

Body mass index at cut-off value 18.5 kg/m2 is currently the commonly used indicator for malnutrition screening in hospitals in Vietnam. This study, however, demonstrates that the routine use of BMI alone at this cut-off value is absolutely not appropriate to identify malnutrition in hospitals in Vietnam due to its very low sensitivity (39.6%) and low PPV (39.4%). BMI at 21 kg/m2 had better validity compared to BMI at cut-off value 18.5 kg/m2 although it had lower validity compared to screening tools. This study, therefore, showed that a screening tool is better than BMI alone to identify malnutrition among hospitalized adults in Vietnam. The use of BMI if applicable, should be at the cut-off value of 21 kg/m2 and should be reserved in a very rare circumstances/ environments where the resources are very constrained and/or works are overload.

Although MST, NRS-2002 and MUST have all been used as nutrition screening tools for adult populations in acute care settings in Asian countries [11], they were rarely validated for use in these populations. Instead, most of studies in Asian countries focused on the development and validation of screening tools for use in predominantly elderly populations as seen in the Chinese Nutrition Screen CNS (China) [26], the Malnutrition Risk Screening Tool – Hospital or MRST-H (Malaysia) [27], and the validation of NRS-2002 and MNA-SF in Singapore elderly [10]. In our study, we found some widely used international screening tools and their modification were valid for use among Vietnamese adult populations. Their validity and applicability among other adult populations in Asian countries needs further exploration.

For adult population in Asian countries, a nutritional screening tool was developed for use in acute care setting in Singapore (the 3-min nutrition screening or 3-min NS) [28]. This screening tool contains three questions on unintentional weight loss, nutritional intake and muscle wastage. BMI was not included in this tool due to the practical issues associated with measuring BMI. Although being used at different cut-off points, the 3-min NS showed that questions on unintentional weight loss and nutrition intake were valid for use in nutritional screening in a hospitalized Singaporean population. In addition, the 3-min NS also showed that the use of only two questions on unintentional weight loss and nutritional intake did not demonstrate adequate validity unless combined with a question on muscle wastage. This is similar to our findings where the combination of unintentional weight loss and nutritional intake with BMI increased the validity of screening tools for use in a Vietnamese population.

Validity in terms of specificity and sensitivity is not the only issue to be considered in deciding on an appropriate screening tools for hospitalized adults in HCMC Vietnam. Currently the resources for and focus on nutrition care in general and nutrition screening specifically are very limited in healthcare facilities in HCMC Vietnam. Therefore, selection of an appropriate screening tool for use in Vietnam hospitals will not only depend on the validity of the screening tools themselves but will also depend on other factors such as the acceptability and feasibility of the screening tools as administered by the proposed administrators (in this case medical doctors and nurses) in hospitals. This study has established the validity of the most used international screening tools, however, acceptability, and feasibility need to be further investigated.

The current study had some strengths, such as using a highly representative sample for hospital patients population, a high response rate (98.7%), data collection by staff with experience in nutrition and research, and strong support from leaders, staff, and patients from participating hospitals, weight, and height were taken directly by research team rather than collected from medical notes. The results from nutritional assessments (using SGA) were not blinded to the nutrition screening results (using screening tools) was limitation.

In conclusion, based on specificity and sensitivity, the first choice for the most appropriate screening tool for use in Vietnam is the NRS-2002, following by the MST + BMI, MUST, and BMI alone at the cut-off value of 21 kg/m2. A prospective study is required to validate the screening tools found in this study.

References

Norman K, Pichard C, Lochs H, Pirlich M. Prognostic impact of disease-related malnutrition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:5–15.

Cuong TQ, Banks M, Hannan-Jones M, Diep DTN, Gallegos D. Prevalence and associated risk factors of malnutrition among hospitalized adults in a multisite study in Ho Chi Minh City Vietnam. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 2017, https://doi.org/10.6133/apjcn.042018.07.

Braunschweig C, Gomez S, Sheean PM. Impact of declines in nutritional status on outcomes in adult patients hospitalized for more than 7 days. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100:1316–22.

Barker LA, Gout BS, Crowe TC. Hospital malnutrition: prevalence, identification and impact on patients and the healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:514–27.

Mueller C, Compher C, Ellen DMASPEN. Clinical guidelines: nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2011;35:16–24.

Ferguson M, Capra S, Bauer J, Banks M. Development of a valid and reliable malnutrition screening tool for adult acute hospital patients. Nutrition. 1999;15:458–64.

Elia M. The 'MUST' report. Nutritional screening for adults: a multidisciplinary responsibility. Developmentand use of the 'Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool' (MUST) for adults. BAPEN, UK, 2003.

Rubenstein LZ, Harker JO, Salvà A, Guigoz Y, Vellas B. Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M366–72.

Kondrup J, Rasmussen HH, Hamberg OLE, Stanga Z, Grp EW, Ad Hoc EWG. Nutritional risk screening (NRS 2002): a new method based on an analysis of controlled clinical trials. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:321–36.

Lim YP Malnutrition and clinical outcomes in elderly patients from a Singapore acute hospital. PhD Thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, QLD, 2010.

Higashiguchi T, Arai H, Claytor LH, Kuzuya M, Kotani J, Lee S-D, et al. Taking action against malnutrition in Asian healthcare settings: an initiative of a Northeast Asia study group. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2017;26:202–11.

Deurenberg P, Deurenberg-Yap M. Differences in body-composition assumptions across ethnic groups: practical consequences. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4:377–83.

Lohmann TG, Roche AF. Anthropometric standardization reference manual. Martorell Reditor. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1988.

Platek ME, Hertroijs DFL, Nicholson JM, Parekh N, Sensitivity and specificity of malnutrition screening tools used in the adult hospitalized patient setting a systematic review. Topics Clin Nutr. 2015;30:289–301.

van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Guaitoli PR, Jansma EP, de Vet HCW. Nutrition screening tools: does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin Nutr. 2014;33:39–58.

Anthony PS. Nutrition screening tools for hospitalized patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:373–82.

Skipper A, Ferguson M, Thompson K, Castellanos VH, Porcari J. Nutrition screening tools: an analysis of the evidence. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012;36:292–8.

Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000;25:3186–91.

Hanna KL, Glen KD, Lau BT, Tran CQ, Truong NT, Gallegos D. Relationship between malnutrition and selected risk factors in two hospitals in Vietnam. Nutr Diet. 2016;73:59–66.

Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson RA, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1987;11:8–13.

White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, Malone A, Schofield M. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:730–8.

Cederholm T, Bosaeus I, Barazzoni R, Bauer J, Van Gossum A, Klek S, et al. Diagnostic criteria for malnutrition - an ESPEN consensus statement. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:335–40.

StataCorp. 2007. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP..

Hajian-Tilaki K. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis for medical diagnostic test evaluation. Casp J Intern Med. 2013;4:627–35.

Kim JY, Wie GA, Cho YA, Kim SY, Kim SM, Son KH, et al. Development and validation of a nutrition screening tool for hospitalized cancer patients. Clin Nutr. 2011;30:724–9.

Woo J, Chumlea WC, Sun SS, Kwok T, Lui HH, Hui E, et al. Development of the Chinese nutrition screen (CNS) for use in institutional settings. J Nutr Health Aging. 2005;9:203–10.

Sakinah H, Suzana S, Noor Aini MY, Philip Poi JH, Shahrul Bahyah K. Development of a local malnutrition risk screening tool-hospital (MRST-H) for hospitalised elderly patients. Malays J Nutr. 2012;18:137–47.

Lim S-L, Tong C-Y, Ang E, Lee EJ-C, Loke W-C, Chen Y, et al. Development and validation of 3-minute nutrition screening (3-MinNS) tool for acute hospital patients in Singapore. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:395–403.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank (1) Staff of Department of Nutrition and Dietetics from six participating hospitals, and staff from Nutrition Centre Ho Chi Minh City for their time and effort in helping collect data for this study; (2) statisticians Edward Gosden for his statistical advices; (3) Dr. Ekta Agarwal for her advices on the development of a protocol at an early stage. TQC was supported by an Australia Award PhD scholarship.

Author contribution

This study was done as part of PhD project of TQC and was supervised by DG, MHJ, MB, and DTND. The Project was planned and designed by TQC, DG, MB, MHJ, and DTND. Data was collected, analyzed by TQC. The original manuscript was written by TQC and then all authors participating in editing and revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tran, Q.C., Banks, M., Hannan-Jones, M. et al. Validity of four nutritional screening tools against subjective global assessment for inpatient adults in a low-middle income country in Asia. Eur J Clin Nutr 72, 979–985 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0217-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0217-8

- Springer Nature Limited