Abstract

Antithymocyte globulin (ATG) is commonly used for graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis in unrelated donor allogeneic transplantation (Allo-HSCT). However, its use is still controversial in matched sibling donor (MSD) Allo-HSCT, notably after reduced intensity conditioning (RIC). ATG dose may influence the outcome, explaining in part the discordant conclusions in MSD Allo-HSCT. We, therefore, analyzed the impact of ATG doses in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission undergoing RIC Allo-HSCT from a MSD. We analyzed 234 patients from the EBMT registry and compared outcome according to given ATG dose (high dose: ≥ 6 mg/kg, n = 39 or low dose: < 6 mg/kg, n = 195). No difference was found in the cumulative incidence of acute (grade 2–4: high dose vs. low dose: 21% vs. 13%, p = 0.334; adjusted hazard ratio (HR): 1.20, p = 0.712) and chronic GVHD (extensive: high dose vs. low dose: 19% vs. 18%, p = 0.897; adjusted HR: 1.01, p = 0.980). In contrast, high dose of ATG significantly increased the incidence of relapse (52% vs. 26%, p = 0.011; adjusted HR: 1.31, p = 0.001) leading to impaired outcome (HR progression-free survival (PFS): 1.23, p = 0.002; HR overall survival (OS): 1.17, p = 0.029; HR GVHD and relapse-free survival (GRFS): 1.20, p = 0.005). We conclude that an ATG dose <6 mg/kg is sufficient for GVHD prophylaxis, while higher doses impair disease control and outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of antithymocyte globulin (ATG) as a part of the conditioning regimen was reported as effective for prophylaxis of graft-vs.-host disease (GVHD) without increasing the risk of relapse in the setting of unrelated donor myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Allo-HSCT) [1,2,3,4]. However, the role of ATG for HLA-identical sibling Allo-HSCT is still controversial after reduced intensity conditioning (RIC). A large CIBMTR analysis suggested that the use of ATG after RIC reduced the incidence of GVHD but increased the risk of relapse when a matched sibling donor (MSD) is used, leading to worse outcome compared with patients who did not receive any in vivo T-cell depletion [5]. In contrast, the EBMT comparison, focused on acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients undergoing RIC Allo-HSCT from a MSD in first complete remission (CR1), showed that the use of ATG reduced the incidence of GVHD without increasing the risk of relapse [6]. These discordant conclusions could be explained by the different median doses of ATG used, 7 and 5 mg/kg in the CIBMTR and EBMT studies, respectively. Thus, we hypothesized that the dose of ATG is a critical issue and could be a major determinant of outcome after Allo-HSCT. This was previously suggested in different retrospective analyses, but the relative low number of patients and/or the heterogeneity in baseline characteristics (donor, graft source, GVHD prophylaxis) did not allow drawing strong conclusions [7,8,9,10]. Here, we investigated the impact of the ATG dose as part of a RIC regimen on the outcome of patients transplanted for CR1 AML, in the specific setting of MSD.

Materials and methods

Data collection and selection criteria

This retrospective study was performed by the Acute Leukemia Working Party (ALWP) of the European society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Patients with the following criteria were included for this analysis: (1) first Allo-HSCT between January 2000 and February 2013; (2) AML in CR1; (3) peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) from a MSD as graft source; (4) RIC regimen using ATG (Thymoglobulin); and (5) cyclosporine A (CsA) alone as post-graft immunosuppression. Patients receiving ex vivo manipulated graft were excluded. Data were collected using the EBMT minimum essential data forms and additional information concerning the dose of ATG was provided using specific request forms. Forty-three voluntary EBMT centers participated in this study (Supplemental File). The study was approved by the scientific committee of ALWP of EBMT, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki for clinical research. All patients gave signed informed consent for data collection and participation in retrospective database analyses.

Statistical analyses

Patients who received ATG doses of 6 mg/kg or more constituted the high-dose group because this corresponds to more than 2 days of ATG at 2.5 mg/kg/day. The remaining patients formed the low-dose group. Both high-dose and low-dose groups were compared according to classical end points. Acute and chronic GVHD were classified using the Glucksberg and Seattle classical scales, respectively [11, 12]. The cumulative incidences of GVHD, relapse (CIR), and non-relapse mortality (NRM) were estimated using the Prentice methods, and the Gray test was used for univariate comparisons [13, 14]. Death from any cause before the occurrence of GVHD was considered as a competing event for the incidence of GVHD. Death in CR1 defined the event for the incidence of NRM and was considered as a competing event for the CIR. The Kaplan–Meier method and log-rank test were used to calculate and to compare the progression-free (PFS), overall survivals (OS), and GVHD and relapse-free survival (GRFS) [15]. In GRFS calculation, grade 3–4 acute GVHD, extensive chronic GVHD, relapse, and death were considered as relevant events [16]. All time-to-event calculations start at the time of Allo-HSCT. All patients were censored at last contact in the absence of relevant events. The impact of ATG doses (as continuous and categorical variable) was evaluated using a multivariate Cox model adjusted by cytogenetics (adverse vs. other), time from diagnosis to Allo-HSCT (≤ vs. >6 months), age at the time of Allo-HSCT (≤ vs. >55 years), RIC regimen types (busulfan-base vs. other), and transplantation period (2000–2008 vs. 2009–2013) [17]. Statistical analyses were computed using R-project 3.2.1 software.

Results

Patient and transplantation characteristics

We analyzed 234 consecutive patients with a median age of 55 years (range: 22–70; Table 1). Forty-one (18%) patients had unfavorable cytogenetics and 214 (90%) received a busulfan-based RIC regimen (total busulfan dose of 260 mg/m² or 6.4 mg/kg). ATG was given at the dose of 6 mg/kg or more to 39 patients (high-dose group), while 195 received lower dose (low-dose group). The median ATG doses in the high-dose and low-dose groups were 7.5 (6–10) and 5 (2–5.5) mg/kg, respectively. In the low-dose group, most of patients received 5 mg/kg of ATG, while only 35 patients (18%) had very low-ATG dose, below 3 mg/kg. The very low-dose group had similar disease risk of relapse compared with other groups according to cytogenetics (20% of adverse cytogenetics). Patients in the high-dose group were more frequently transplanted before 2009 (p = 0.022) and received slightly more frequently a RIC regimen without busulfan (p = 0.053). Age, time from diagnosis to Allo-HSCT, and cytogenetic risk groups were equally distributed in both high- and low-ATG dose groups.

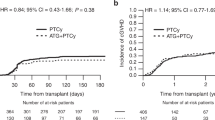

GVHD and NRM

In the whole cohort, the incidences of grade 2–4 and grade 3–4 acute GVHD at day +100 were 15% and 7%, respectively. No difference was found between the two dose groups (grade 2–4: high dose vs. low dose: 21% and 13%, p = 0.334; grade 3–4: high dose vs. low dose: 10% vs. 7%, p = 0.579; Table 2, Fig. 1a). At 2 years, the cumulative incidences in all patients of limited + extensive and extensive chronic GVHD were 40% and 18%, respectively, without significant difference according to ATG dose (limited + extensive: high dose vs. low dose: 40% vs. 40%, p = 0.824; extensive: high dose vs. low dose: 19% vs. 18%, p = 0.897; Table 2, Fig. 1b). Among low-dose group patients, those who received a dose of ATG lower than 3 mg/kg had a trend for higher incidence of chronic GVHD (54%) compared to those who received a dose between 3 and 5.5 mg/kg (37%, p = 0.054). The cumulative incidences of NRM on day +100 were 13% and 10% in the high-dose and low-dose groups, respectively, leading to similar 2-year NRM (high dose vs. low dose: 15% vs. 14%, p = 0.878; Table 2, Fig. 2a). Adjusted Cox model confirmed that both acute (hazard ratio (HR): 1.20, p = 0.712) and chronic (HR: 1.01, p = 0.980) GVHD, as well as NRM (HR: 1.49, p = 0.399) were comparable between both dose groups (Table 3).

Relapse and survivals

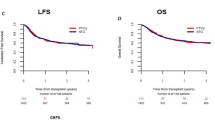

The CIR at 2 years was twofold higher in the high-dose compared to the low-dose group (52% vs. 26%, respectively, p = 0.011, Table 2, Fig. 2b). This led to significantly shorter PFS (high-dose vs. low-dose, 2-year estimates: 33% vs. 60%, p = 0.005; Table 2, Fig. 3a) and OS (high-dose vs. low-dose, 2-year estimates: 49% vs. 64%, p = 0.041; Table 2, Fig. 3b) in patients receiving high ATG doses. In addition, GRFS was significantly lower in the high-dose group (high-dose vs. low-dose, 2-year estimates: 28% vs. 50%, p = 0.023; Table 2, Supplement Fig. 1). Among the low-dose group patients, there was no difference between those receiving less and more than 3 mg/kg of ATG dose in CIR (p = 0.100), PFS (p = 0.179), OS (p = 0.289), and GRFS (p = 0.272). Adjusted multivariate model (Table 3) showed that the use of high ATG doses (as a continuous variable) was significantly associated with higher CIR (HR: 1.31, p = 0.001) and shorter PFS (HR: 1.23, p = 0.002), OS (HR: 1.17, p = 0.029), and GRFS (HR: 1.20, p = 0.005). In contrast, no difference was found in the incidence of both acute (HR: 0.98, p = 0.856) and chronic (HR: 0.96, p = 0.845) GVHD or NRM (HR: 1.05, p = 0.747). When analyzing ATG dose as a categorical variable, we found that the use of ATG ≥ 6 mg/kg was associated with significantly higher CIR, leading to significantly shorter PFS and GRFS, and to a trend for shorter OS (Table 3). Adverse cytogenetics was the only other independent factor that was significantly associated with higher CIR (HR: 2.71, p < 0.001) and shorter PFS (HR: 2.83, p < 0.001) and OS (HR: 3.16, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the role of the ATG dose as part of the conditioning regimen on the outcome after Allo-HSCT. To deal with confounding factors such as disease risk, GVHD prophylaxis, conditioning intensity, or donor and graft source, we focused on patients with CR1 AML undergoing PBSC RIC Allo-HSCT from a HLA-identical sibling donor. Patients who received GVHD prophylaxis other than CSA alone were excluded, on the basis that we previously reported worse outcome using CSA + MMF in this setting [18]. On this cohort of patients receiving ATG-based RIC regimen, we found low incidences of severe forms of acute and chronic GVHD (7% and 18%, respectively), supporting the use of ATG as an efficient GVHD prophylaxis in the setting of MSD Allo-HSCT. This is in line with a previously reported series of HLA-identical sibling Allo-HSCT showing 3–11% of grade 3–4 acute GVHD and 14–27% of extensive chronic GVHD when ATG is given as GVHD prophylaxis [6, 19,20,21,22]. Interestingly, we found no additional advantage using ATG doses ≥6 mg/kg, suggesting that ATG doses below are likely sufficient for GVHD prophylaxis.

In contrast, ATG doses ≥6 mg/kg were strongly associated with an increased incidence of relapse, leading to worse survivals. A similar conclusion was previously reported in the setting of unrelated Allo-HSCT [8]. These results underline the importance of ATG dosage on the outcome, and may partly explain the discordance between the conclusions from the CIBMTR and EBMT analyses, in which the median doses of ATG were 7 and 5 mg/kg, respectively. Indeed, a worse outcome was observed in patients receiving ATG in the CIBMTR study, while no difference was found in the EBMT study [5, 6]. In addition, high ATG doses may also impair outcome because of profound immunosuppression leading to higher incidence of infections. Indeed, we previously reported that high ATG doses increase the incidence of early CMV reactivations, while lower doses preserve anti-CMV-specific T cells [23,24,25]. In addition, it was shown that the use of ATG as part of RIC regimen is associated with significantly higher EBV reactivations, but did not significantly impair outcome when a rituximab preemptive treatment strategy is used (no PTLD was observed). [26] In a randomized trail evaluating the impact of ATG-Fresenius on outcome after myeloablative Allo-HSCT from MSD, no increased incidence of CMV or EBV reactivation was observed in the ATG arm [27]. This confirms that the use of low-ATG dose does not strongly impair immunological recovery against both CMV and EBV.

These results support the need for a fine tuning of ATG doses to obtain an effective GVHD prophylaxis without increasing the risk of relapse. On the basis of our data, we suggest that a total dose of about 5 mg/kg may represent a good balance, while the use of higher doses significantly increases the incidence of relapse. In contrast, very low doses of ATG (2.5 mg/kg) were previously reported as insufficient for GVHD prophylaxis compared to the 5 mg/kg dose, with ~30% and 70% of acute and chronic GVHD, respectively [28]. In our series, we found a trend for higher incidence of chronic GVHD when very low doses were given (54%, p = 0.054). The low number of patients receiving less than 3 mg/kg of ATG may explain in part that statistical significance was not reached in our study.

Taken together, the data suggest that, in the setting of HLA-identical sibling Allo-HSCT, the use of low doses (below 6 mg/kg) of ATG does not impair survival. Furthermore, the advantage of including ATG in GVHD prophylaxis may help preserving the quality of life after Allo-HSCT [29]. This aspect was objectively assessed and supported in a few prospective studies [3, 21]. It is important to notice that the good balance obtained here with low-dose Thymoglobulin cannot be translated easily in different situations. Schleuning et al. reported in the context of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia undergoing bone marrow myeloablative Allo-HSCT from unrelated donor that higher doses of ATG (Fresenius ≥ 60 mg/kg total dose) improved survival by reducing acute GVHD [30].

In conclusion, our results encourage the use of ATG as an efficient GVHD prophylaxis in RIC preparative regimen prior to PBSC Allo-HSCT from HLA-identical sibling donor, and caution against the use of higher doses (≥ 6 mg/kg), which significantly increase the risk of relapse. At present, this conclusion applies only to patients in CR1 AML using rabbit ATG Thymoglobulin. Different conclusions may be considered in other settings of disease and donor types, conditioning intensity, and/or ATG formulation. A prospective randomized trial of ATG vs. no ATG in matched sibling myeloablative Allo-HSCT was recently published, and also supports the use of ATG (Fresenius) as an effective GVHD prophylaxis, without impairing disease control, in this donor situation [27].

References

Finke J, Bethge WA, Schmoor C, Ottinger HD, Stelljes M, Zander AR, et al. Standard graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin in haematopoietic cell transplantation from matched unrelated donors: a randomised, open-label, multicentre phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:855–64.

Bacigalupo A, Lamparelli T, Bruzzi P, Guidi S, Alessandrino PE, di Bartolomeo P, et al. Antithymocyte globulin for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in transplants from unrelated donors: 2 randomized studies from Gruppo Italiano Trapianti Midollo Osseo (GITMO). Blood. 2001;98:2942–7.

Walker I, Panzarella T, Couban S, Couture F, Devins G, Elemary M, et al. Pretreatment with anti-thymocyte globulin versus no anti-thymocyte globulin in patients with haematological malignancies undergoing haemopoietic cell transplantation from unrelated donors: a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00462-3.

Soiffer RJ, Kim HT, McGuirk J, Horwitz ME, Johnston L, Patnaik MM, et al. Prospective, randomized, double-blind, phase III clinical trial of anti-T-lymphocyte globulin to assess impact on chronic graft-versus-host disease-free survival in patients undergoing HLA-matched unrelated myeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2017. doi:JCO2017758177.

Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, Kan F, Artz A, Champlin RE, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117:6963–70.

Baron F, Labopin M, Blaise D, Lopez-Corral L, Vigouroux S, Craddock C, et al. Impact of in vivo T-cell depletion on outcome of AML patients in first CR given peripheral blood stem cells and reduced-intensity conditioning allo-SCT from a HLA-identical sibling donor: a report from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:389–96.

Crocchiolo R, Esterni B, Castagna L, Fürst S, El-Cheikh J, Devillier R, et al. Two days of antithymocyte globulin are associated with a reduced incidence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease in reduced-intensity conditioning transplantation for hematologic diseases. Cancer. 2013;119:986–92.

Remberger M, Ringdén O, Hägglund H, Svahn B-M, Ljungman P, Uhlin M, et al. A high antithymocyte globulin dose increases the risk of relapse after reduced intensity conditioning HSCT with unrelated donors. Clin Transplant. 2013;27:E368–74.

Mohty M, Bay J-O, Faucher C, Choufi B, Bilger K, Tournilhac O, et al. Graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic transplantation from HLA-identical sibling with antithymocyte globulin-based reduced-intensity preparative regimen. Blood. 2003;102:470–6.

Storek J, Mohty M, Boelens JJ. Rabbit anti-T cell globulin in allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2015;21:959–70.

Glucksberg H, Storb R, Fefer A, Buckner CD, Neiman PE, Clift RA, et al. Clinical manifestations of graft-versus-host disease in human recipients of marrow from HL-A-matched sibling donors. Transplantation. 1974;18:295–304.

Shulman HM, Sullivan KM, Weiden PL, McDonald GB, Striker GE, Sale GE, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host syndrome in man. A long-term clinicopathologic study of 20 Seattle patients. Am J Med. 1980;69:204–17.

Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The analysis of failure times in the presence of competing risks. Biometrics. 1978;34:541–54.

Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–54.

Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81.

Holtan SG, DeFor TE, Lazaryan A, Bejanyan N, Arora M, Brunstein CG, et al. Composite endpoint of graft-versus-host disease-free, relapse-free survival after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood. 2015. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-10-609032.

Cox D. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220.

Rubio MT, Labopin M, Blaise D, Socié G, Contreras RR, Chevallier P, et al. The impact of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplant in acute myeloid leukemia: a study from the Acute Leukemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2015;100:683–9.

Wolschke C, Zabelina T, Ayuk F, Alchalby H, Berger J, Klyuchnikov E, et al. Effective prevention of GVHD using in vivo T-cell depletion with anti-lymphocyte globulin in HLA-identical or -mismatched sibling peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2014;49:126–30.

Russell JA, Turner AR, Larratt L, Chaudhry A, Morris D, Brown C, et al. Adult recipients of matched related donor blood cell transplants given myeloablative regimens including pretransplant antithymocyte globulin have lower mortality related to graft-versus-host disease: a matched pair analysis. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:299–306.

Blaise D, Devillier R, Lecoroller-Sorriano A-G, Boher J-M, Boyer-Chammard A, Tabrizi R, et al. Low non-relapse mortality and long-term preserved quality of life in older patients undergoing matched related donor allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a prospective multicenter phase II trial. Haematologica. 2015;100:269–74.

Bonifazi F, Bandini G, Arpinati M, Tolomelli G, Stanzani M, Motta MR, et al. Intensification of GVHD prophylaxis with low-dose ATG-F before allogeneic PBSC transplantation from HLA-identical siblings in adult patients with hematological malignancies: results from a retrospective analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:1105–11.

Mohty M, Jacot W, Faucher C, Bay JO, Zandotti C, Collet L, et al. Infectious complications following allogeneic HLA-identical sibling transplantation with antithymocyte globulin-based reduced intensity preparative regimen. Leukemia. 2003;17:2168–77.

Mohty M, Faucher C, Vey N, Stoppa AM, Viret F, Chabbert I, et al. High rate of secondary viral and bacterial infections in patients undergoing allogeneic bone marrow mini-transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26:251–5.

Mohty M, Mohty AM, Blaise D, Faucher C, Bilger K, Isnardon D, et al. Cytomegalovirus-specific immune recovery following allogeneic HLA-identical sibling transplantation with reduced-intensity preparative regimen. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;33:839–46.

Peric Z, Cahu X, Chevallier P, Brissot E, Malard F, Guillaume T, et al. Features of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) reactivation after reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia. 2011;25:932–8.

Kröger N, Solano C, Wolschke C, Bandini G, Patriarca F, Pini M, et al. Antilymphocyte globulin for prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease. New Engl J Med. 2016;374:43–53.

Devillier R, Crocchiolo R, Castagna L, Fürst S, El Cheikh J, Faucher C, et al. The increase from 2.5 to 5 mg/kg of rabbit anti-thymocyte-globulin dose in reduced intensity conditioning reduces acute and chronic GVHD for patients with myeloid malignancies undergoing allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:639–45.

Yu Z-P, Ding J-H, Wu F, Liu J, Wang J, Cheng J, et al. Quality of life of patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with antihuman thymocyte globulin. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:593–9.

Schleuning M, Günther W, Tischer J, Ledderose G, Kolb H-J. Dose-dependent effects of in vivo antithymocyte globulin during conditioning for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from unrelated donors in patients with chronic phase CML. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003;32:243–50.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all EBMT participating centers and their datamanagers (Supplemental file). We thank J.V. Melo (University of Adelaide, Australia, and Imperial College, London, UK) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Author’s contributions

DB, AN and MM designed the study. RD and ML performed statistical analyses. RD, ML, DB, AN, and MM analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. RD, PC, MPL, GS, AH, JHB, JYC, GRG, GM, DD, MM, NF, FC, FB, DB, AN and MM included patients. All authors commented and approved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MM, AN, JYC, FB, and DB received lectures honoraria and research support from Sanofi whose product is discussed in this manuscript. GS received lectures honoraria from Fresenius Biotech. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Arnon Nagler and Mohamad Mohty contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devillier, R., Labopin, M., Chevallier, P. et al. Impact of antithymocyte globulin doses in reduced intensity conditioning before allogeneic transplantation from matched sibling donor for patients with acute myeloid leukemia: a report from the acute leukemia working party of European group of Bone Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 53, 431–437 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-017-0043-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41409-017-0043-y

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

The role of anti-thymocyte globulin in allogeneic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) from HLA-matched unrelated donors (MUD) for secondary AML in remission: a study from the ALWP /EBMT

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2023)

-

Higher cyclosporine-A concentration increases the risk of relapse in AML following allogeneic stem cell transplantation from unrelated donors using anti-thymocyte globulin

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Outcomes of patients with hematological malignancies who undergo unrelated donor hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with ATG-Fresenius versus ATG-Genzyme

Annals of Hematology (2023)

-

Efficacy of low dose antithymocyte globulin on overall survival, relapse rate, and infectious complications following allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for leukemia in children

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2021)

-

Rabbit ATG/ATLG in preventing graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: consensus-based recommendations by an international expert panel

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2020)