Abstract

Psychotic symptoms, defined as the occurrence of delusions or hallucinations, are frequent in Alzheimer disease (AD with psychosis, AD + P). AD + P affects ~50% of individuals with AD, identifies a subgroup with poor outcomes, and is associated with a greater degree of cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, compared to subjects without psychosis (AD − P). Although the estimated heritability of AD + P is 61%, genetic sources of risk are unknown. We report a genome-wide meta-analysis of 12,317 AD subjects, 5445 AD + P. Results showed common genetic variation accounted for a significant portion of heritability. Two loci, one in ENPP6 (rs9994623, O.R. (95%CI) 1.16 (1.10, 1.22), p = 1.26 × 10−8) and one spanning the 3′-UTR of an alternatively spliced transcript of SUMF1 (rs201109606, O.R. 0.65 (0.56–0.76), p = 3.24 × 10−8), had genome-wide significant associations with AD + P. Gene-based analysis identified a significant association with APOE, due to the APOE risk haplotype ε4. AD + P demonstrated negative genetic correlations with cognitive and educational attainment and positive genetic correlation with depressive symptoms. We previously observed a negative genetic correlation with schizophrenia; instead, we now found a stronger negative correlation with the related phenotype of bipolar disorder. Analysis of polygenic risk scores supported this genetic correlation and documented a positive genetic correlation with risk variation for AD, beyond the effect of ε4. We also document a small set of SNPs likely to affect risk for AD + P and AD or schizophrenia. These findings provide the first unbiased identification of the association of psychosis in AD with common genetic variation and provide insights into its genetic architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychotic symptoms, defined as the occurrence of delusions or hallucinations, constitute a phenotype within Alzheimer disease (AD + Psychosis, AD + P) that affects ~ 40–60% of individuals with AD and is associated with poor outcomes [1]. In comparison to AD subjects without psychosis (AD − P), AD + P subjects have greater cognitive impairments and experience more rapid declines in cognition and function that begin prior to psychosis onset [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. AD + P is also often associated with increased rates of concurrent neuropsychiatric symptoms, including agitation [10], aggression [11, 12], and depression [5, 13,14,15]. As a consequence, AD + P is associated with increased rates of other poor outcomes, including greater distress for family and caregivers [16], higher institutionalization rates [17,18,19,20], worse health [21], and increased mortality [22] compared to AD − P patients.

The AD + P phenotype is well suited for genetic studies when careful attention is paid to excluding potential phenocopies of both AD + P and AD − P. For example, we have shown that the heritability of AD + P is greatest when requiring the presence of multiple or recurrent psychotic symptoms, rather than a one-time occurrence of a single symptom [23]. Similarly, because psychotic symptoms typically emerge in the transition from mild to moderate stages of AD [5], individuals without psychosis who are still in the early stages of disease may later manifest psychosis, and therefore, need to be excluded from the analysis. Using these approaches to phenotypic characterization, we have previously reported familial aggregation of AD + P [24], which has since been replicated in two independent cohorts [5, 25]. We further estimated the heritability of the presence or absence of psychosis in AD at 61% [23, 26].

Thus, AD + P is likely to be strongly influenced by genetic variation. To date, no study has identified genome-wide significant associations with AD + P, largely due to the small sample sizes of prior studies. However, in prior reports we identified negative genetic correlation of AD + P risk with risk for schizophrenia [27, 28]. We now report a large genome-wide association meta-analysis of 12,317 AD subjects with and without psychosis. We identified two loci with genome-wide significant associations with AD + P, in ENPP6 and SUMF1. In gene-based analyses, only APOE (p = 1.23 × 10−6) reached the criterion for genome-wide significance. AD + P was negatively genetically correlated with educational attainment and positively with depressive symptoms. Surprisingly, AD + P was not significantly genetically correlated with schizophrenia, but it was negatively correlated with bipolar disorder. Analysis of polygenic risk scores derived from schizophrenia (PRSSZ), and bipolar disorder (PRSBP) GWAS, support these genetic correlations. However, the relationship of schizophrenia risk to AD + P appears subtle, with some established risk SNPs for schizophrenia likely to confer risk for AD + P, while others confer protection.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study analyzed samples from 12,317 subjects diagnosed with possible, probable [29], and when available, autopsy-confirmed definite [30] Alzheimer disease (for subject characteristics see Table 1a). Diagnoses were made based on diagnostic evaluations, cognitive testing, and in some cases neuropathologic assessment, conducted during subjects’ participation in the following eight source programs as previously described: the Fundació ACE Barcelona Alzheimer Treatment and Research Center (ACE/GR@ACE) [31,32,33], a Consortium of National Institute on Aging Alzheimer Disease Centers (ADC) [34], Eli Lilly and Company (LILLY) [35, 36], the Norwegian, Exeter and King’s College Consortium for Genetics of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Dementia (NEXGENS) [37,38,39,40,41,42], the National Institute on Aging’s Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study (NIA-LOAD) [5, 26], the National Institute of Mental Health Genetics Initiative AD Cohort (NIMH) [24], the University of Pittsburgh Alzheimer Disease Research Center (PITT ADRC) [43, 44], and the MRC genetic resource for Late-onset AD included in the Genetic and Environmental Risk in AD Consortium (UK-Cardiff) [27, 31, 45]. Collection of clinical data and genetic samples were approved by each source program’s local Institutional Review Board or Medical Ethics Committee, as appropriate.

Characterization of psychosis

Subjects were characterized for the presence or absence of delusions and hallucinations within the individual source programs (including their sub-studies) using the CERAD behavioral rating scale [46] (PITT ADRC and NIA-LOAD), Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q [47], NIA-LOAD, ADC, NEXGENS), NPI-Q Spanish Language Version [48] (ACE/GR@ACE), NPI [49] (UK-Cardiff, NEXGENS, LILLY), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale [50] (NIMH). Each of these instruments has established reliability in AD [5, 51], and we have previously used all successfully in analyses of psychosis in AD subjects [4, 5, 7, 23, 43]. AD + P was defined by the presence of persistent hallucinations or delusions throughout the course of dementia, AD − P was defined by the absence of all symptoms at all assessments. However, because psychotic symptoms typically emerge in the transition from mild to moderate stages of AD [5], individuals without psychosis, but who were still in the early stages of disease at their last assessment (CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument [52] score <1, mini-mental state examination score [53] >20), were considered to be at substantial risk of developing AD + P later in their course. Thus, these individuals were excluded from the analysis. We have used these approaches to characterizing and defining AD + P and AD − P in multiple studies demonstrating the heritability and association with genetic variation of the AD + P phenotype [5, 23, 24, 26,27,28, 54].

For additional detail of each source program’s clinical assessment methodology and demographics, see Supplementary Material.

Genotypes

Six of the eight program sources provided us with either blood (ACE/GR@ACE) or DNA samples (PITT ADRC, UK-Cardiff, NIA-LOAD, ADC, NIMH), all of which were processed by the Genomics Core Lab at the University of Pittsburgh. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood samples using the Qiamp Blood Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). All DNA was quantitated by Pico Green (Thermo Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) and diluted to a DNA concentration of 23 ng/µl. Samples were genotyped at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHoP, Philadelphia, PA) using Illumina’s Global Screening Array (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Prior to genotyping, ChoP confirmed DNA concentrations by Pico Green assay, and performed WGA on samples when necessary.

In addition to the above-mentioned blood and DNA samples, ACE/GR@ACE, LILLY, and NIA-LOAD provided us with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data. For the ADC, SNP array data was provided by the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC). NEXGENS provided genome-wide association (GWA) statistics for the comparison of AD − P and AD + P. Additional details of the generation of SNP array data for all programs can be found in the Supplementary Material.

Analysis

Data from the eight program sources were processed as four cohorts (Phase 1, Phase 2, GR@ACE, and NEXGENS), based on timing of receipt of the data. Data processing, QC, and statistical analyses were uniform across three of the cohorts for which there were genotypes (Phase 1, Phase 2, GR@ACE), whereas only summary statistics were available for the fourth cohort (NEXGENS). All cohorts were analyzed separately for GWA, then statistics per SNP from these analyses were combined by meta-analysis using METAL [55]. Below we describe quality control procedures for the three genotyped cohorts. For more detail of other methods see the Supplementary Material. Additional details for the NEXGENS cohort have been described previously [56]. Methods were implemented within Plink [57, 58] unless otherwise noted.

Quality Control (QC) was completed by both genotype and by sample from Phase 1, Phase 2, and GR@ACE. After QC, 6,872 AD − P and 5,445 AD + P subjects, distributed across the four cohorts, remained for analysis (Table 1b). We determined ancestry using GemTools analysis [59] of a subset of autosomal SNPs with non-call rate < 0.001 and MAF > 0.05 for Phase 1, Phase 2, and GR@ACE. These SNPs were pruned such that, within a 50 SNP block and a 5 SNP step-size, the linkage disequilibrium r2 < 0.01. For each of the three cohorts, a different subset of SNPs was chosen for ancestry analysis, and the resulting ancestry plots were used to identify the samples in the major European ancestry cluster. Analysis of NEXGENS [56] was restricted to individuals of European ancestry using genetic principal components computed by EIGENSTRAT [60].

Genotypes were imputed using the Sanger Imputation Server [61], the 1000 Genomes Phase3 reference panel [62], and EAGLE2 for pre-phasing [63] for Phase 1, Phase 2, and GR@ACE. Before imputation, the genotypes were harmonized using the perl script HRC-1000G-check-bim-v4.2.5.pl. This resulted in 85,057,462 imputed or genotyped SNPs for each sample. QC of the imputed SNPs included the requirement that the INFO score for a SNP in each data set >0.81; MAF > 0.01; and, among all European ancestry subpopulations defined by GemTools, Fst <0.005. For NEXGENS phasing and imputation was done via the Sanger Imputation Service using the Haplotype Reference Consortium (r1.1) reference panel on all cohorts. After imputation, only SNPs with an imputation quality (INFO) score >0.4 and MAF > 0.05 were retained.

Separate GWA analyses were performed for the Phase 1, Phase 2, and GR@ACE cohorts, to contrast AD + P versus AD − P for the 9,200,578 SNPs using the Plink option –logistic and with adjustment for the three ancestry dimensions (Supplementary Fig. S1–S3). For chromosome X, an additional covariate for sex was included. For NEXGENS, separate logistic regressions, implemented in PLINK for each of the five NEXGENS consortium datasets, were used to contrast AD + P versus AD − P for each SNP, with adjustment for the first 10 ancestry principal components. METAL software was used to conduct inverse-variance weighted fixed effects meta-analysis across the five NEXGENS datasets, applying genomic control [55], to generate the summary statistics used in the current analysis. The four GWAS statistics (Phase 1, Phase 2, GR@ACE, NEXGENS summary), per SNP, were then meta-analyzed using METAL.

Heritability of AD + P using GenomicSEM was estimated from 1126,265 summary statistics from our METAL analysis. Of the 7,105,229 SNPs used for GWAS, 1,126,265 matched to those available on the GenomicSEM website. Also, using genome-wide complex trait analysis (GCTA) [64], heritability was estimated from 9,031 subjects of European ancestry drawn from the Phase 1, Phase 2, and GR@ACE cohorts for which individual genotypes were available (Table 1b). Two eigenvectors were used to control for ancestry, 9,97,105 SNPs were included in the analysis.

Individuals of European ancestry from all four cohorts were used to estimate genetic correlations using LD Score [65] and LD Hub (version 1.9.3) [66]. We selected phenotypes for analysis based on prior studies showing correlations with psychosis in AD (years of schooling, depressive symptoms) or genetic association with AD + P (schizophrenia), or because they are closely related with the above phenotypes. Specifically, we included intelligence, which is genetically correlated with years of schooling and bipolar disorder which is strongly genetically correlated with both depressive symptoms and schizophrenia. Finally, we included AD as it is a necessary condition of AD ± P, and two other neurodegenerative diseases, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Parkinson’s disease, each of which is associated with a neuropathology that may contribute to psychosis risk in AD.

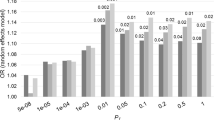

We evaluated how well three different polygenic risk scores could differentiate 9,031 AD + P and AD − P subjects of European ancestry. We used the pruning and thresholding approach [67] to compute a PRS for our subjects, developed from GWAS results for AD (PRSAD) [42], schizophrenia (PRSSZ) [68], and bipolar disorder (PRSBP) [69], separately. We used a set of GWAS p-value thresholds for SNP inclusion in each score (5 × 10−8, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5).

Gene-based analyses were performed on the summary association statistics using the most recent version (1.08b) of MAGMA [70]. For the primary analysis, SNPs were assigned to genes if they lay within the gene boundaries (as defined by NCBI) and the MAGMA “mean” method was used to derive the gene-wide association statistic (the sum of the squared Z statistics for individual SNPs). A secondary analysis assigned SNPs to genes if they lay within 35 kb upstream or 10 kb downstream of the gene boundary, to capture regulatory regions [71].

Gene set enrichment analyses were performed in MAGMA [70], correcting for the number of SNPs in each gene, linkage disequilibrium (LD) between SNPs, and LD between genes. The measure of pathway enrichment is the MAGMA “competitive” test (where the association statistic for genes in the pathway is compared to those of all other protein-coding genes) [72].

Transcriptome-wide association (TWAS) was implemented using the FUSION package [73] was used to perform a TWAS using dorsolateral prefrontal cortex expression data from the CommonMind Consortium and expression data from 13 Brain tissues from the GTEx (Genotype-Tissue expression) consortium (v7) [74]. Results were corrected for multiple testing of multiple genes within each tissue using the Bonferroni method.

See Supplementary Methods for additional details of QC, PRS calculation, pathway analyses, and TWAS.

Results

Association analyses

A total of 12,317 subjects, 6,872 AD − P and 5,445 AD + P, were included in this GWAS analysis (Table 1a). Contrasting AD − P to AD + P genotypes across the genome revealed two significant loci (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table S1). One locus was at 4q24, mapping to an intron of ENPP6 (best SNP rs9994623, O.R. (95%CI) 1.16 (1.10, 1.22), p = 1.26 × 10−8). The other locus was at 3p26.1 (best SNP rs201109606, O.R. 0.65 (0.56–0.76), p = 3.24 × 10−8). This locus spans the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR) of an alternatively spliced variant of SUMF1 (SUMF1-204 ENST00000448413.5). None of the SNPs showing significant association in these loci are annotated as expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) in GTEx. Behavior of the association statistics, as assessed by probability-probability plot (Supplementary Fig. S4), is consistent with the expectation for such analyses, and the genomic control estimate [75], GC = 1.03, shows no evidence for confounding by ancestry.

A Manhattan plot. The x-axis shows genomic position for autosomes and the X chromosome. The y-axis shows statistical significance as −log10 (P). Each point represents an analyzed SNP. The dashed horizontal line represents the threshold for genome-wide significance (p = 5 × 10−8). B–C Zoom plots of the two genome-wide significant loci. The x-axis shows genomic position. The left y-axis shows statistical significance as −log10 (P). Each point represents an analyzed SNP, coded by degree of linkage disequilibrium relative to the most significant SNP within the locus. Recombination rate through the region is shown on the right y-axis. AD Alzheimer Disease, LD linkage disequilibrium, cM centimorgans, Mb megabase.

For the gene-based tests (Supplementary Table S2), only APOE (p = 1.23 × 10−6) reached the criterion for genome-wide significance (p < 2.5 × 10−6) [76]. This association was only significant for SNPs within APOE itself. When the 35/10 kb window around genes was used to assign SNPs, no genes reached genome-wide significance. There was substantial association signal for SNPs in and near APOE, however: the smallest p value achieved was at rs283811 (z = 5.15, p = 2.55 × 10−7), which falls in an intron of NECTIN2 (PVRL2 protein). The second smallest p value occurred for rs429358 (z = 5.12, p = 2.96 × 10−7), which is one of the two SNPs comprising the APOE risk haplotype ε4. These two SNPs, separated by 23,441 bp, were in modest LD (r2 = 0.52, D’ = 0.91 [77]) in the 1000 G CEU population sample. To determine if ε4 count could explain the AD + P association signal at this locus, we first analyzed a subset of our subjects who were characterized for the ε4 haplotype (2,414 AD + P and 2,509 AD − P) by logistic regression of AD + P status (yes/no) on ε4 count, after controlling for three eigenvectors for ancestry. The odds increased significantly with count of ε4 haplotypes (OR = 1.21; 95% CI: 1.11–1.31; p = 8.64 × 10−6). Of the 537 SNPs in this locus, none achieved a p value < 0.0001 in this logistic model after controlling for ε4 count and ancestry (rs2927472 achieved the smallest p value, 0.00053). Next, using the same subjects, we determined the LD of ε4, in terms of r2, with 120 SNPs in the APOE locus, all of which had association statistic |z| > 2.0 based on the GWAS of AD + P. We then regressed the statistics for these SNPs, |z|, on their LD with ε4, yielding a strongly positive slope (b = 3.14, p = 1.90 × 10−41) and explaining 78.5% of the variance in the observed AD + P z-statistics. Thus, we conclude that the preponderance of AD + P association signal in this locus arises from ε4.

For the pathway enrichment analyses (Supplementary Table S3), only the Pathway Interaction Database (PID) IGF1 pathway showed significant enrichment after correction for multiple testing (p = 1.17 × 10−6, q = 0.011), although it was no longer significant when the 35/10 kb window was used (p = 0.0469, q = 0.920). Interestingly, one of the pathways found to be significantly enriched for AD risk in Kunkle et al. [78] (GO:48156, tau protein binding) showed significant enrichment (p = 6.44 × 10−4 and p = 2.21 × 10−3 respectively), albeit not withstanding correction for multiple testing. Given that this pathway includes APOE, the enrichment analysis was repeated excluding genes within 1 Mb of APOE (a total of 70 genes), with results shown in Supplementary Table S3. Removing the genes in the APOE region greatly reduced the significance of GO:48156 (p = 0.0106), suggesting that its enrichment is mainly due to APOE.

TWAS comprised a total of 44,185 gene–tissue combinations (Supplementary Tables S4 and S5). No TWAS association was significant after correction for the number of tests performed in all genes and tissues combined (p < 1.13 × 10−6, Bonferroni correction for 44,185 tests). Two associations were significant after Bonferroni correction for the number of genes tested in their particular tissue: VN1R108P in GTEx7 hippocampus (p = 2.94 × 10−6) and FAM182B in GTEx7 cerebellum (p = 5.51 × 10−6). For both genes, an increase in gene expression was associated with the presence of psychosis.

SNP-based heritability

While earlier studies the AD + P phenotype have shown strong clustering in families and substantial heritability, SNP-based heritability has not been estimated. We estimated it in two ways. First, by analyzing our GWAS statistics using GenomicSEM, SNP-based heritability was estimated at 0.181 ± 0.064 (Chi-square = 8.0, df = 1, p = 0.005). An alternative approach, using the GCTA software, evaluated genotypes genome-wide to determine relationships among the samples and how they partitioned within and between AD + P and AD − P sets. This estimate was 0.312 ± 0.053 (Chi-square = 34.98, df = 1, p = 3.3 × 10−9). The larger estimate probably arises due to greater information contained in estimated genetic relationships, relative to our modestly powered GWAS, although the heritability estimates are not significantly different. The GCTA analysis focused on subjects of European ancestry, genetically determined, to avoid confounding of ancestry.

Genetic correlation, polygenic risk score, and risk SNP analyses

Subjects of European ancestry were also used to estimate genetic correlations of AD + P with select phenotypes available from LD Hub (Table 2). Consistent with clinical observations, AD + P is significantly genetically correlated with “Years of Schooling” (and nearly so with the related phenotype, “Intelligence”) and with “Depressive Symptoms”. In contrast, AD + P was not significantly genetically correlated with AD (Table 2). Nor was AD + P significantly genetically correlated with the two other neurodegenerative disorders evaluated, ALS and Parkinson disease (Table 2).

We previously found a significant relationship between risk for AD + P and schizophrenia [28]. Specifically, we genotyped 94 of 128 SNPs that showed genome-wide-significance for association with schizophrenia in a sample of AD + P subjects. We constructed a predictive score for schizophrenia risk from these SNPs, then assessed whether this score predicted AD + P status in the AD sample. There was a significant negative correlation between the risk score for schizophrenia and AD + P status, which we then replicated by genotyping 60 of the 94 risk SNPs in an independent sample. Now, using SNPs from across the genome and a larger set of AD subjects, results from LD HUB show a negative, but non-significant, genetic correlation with schizophrenia, while showing a negative and significant genetic correlation with bipolar disorder (Table 2). In fact, no SNP with p value < 10−4 for association with psychosis in AD had a p value < 10−5 in the 108 loci associated with schizophrenia [79].

Because bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are genetically correlated, we next asked if our original result for the 94 SNPs could be explained by an overlap of risk SNPs for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. To do so, we tested whether the odds ratios for the association of these SNPs for these disorders [69, 79] were independent. They were not (Supplementary Fig. S5); 91 of 94 SNPs had odds ratios exceeding one for both disorders, whereas 47 were expected under independence (sign test, p = 5.8 × 10−20).

Given the somewhat surprising results for the genetic correlations of AD + P with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and AD, we examined whether PRS scores for each of these disorders could differentiate AD + P versus AD − P subjects. In agreement with the genetic correlation, the PRSBP differentiated AD + P from AD − P, whereas PRSSZ showed little ability to differentiate AD + P from AD − P subjects (Table 3).

By contrast, the PRSAD did not agree with the genetic correlation of AD and AD + P from LD Hub. PRSAD significantly predicted AD + P status, in the direction of increased risk for AD + P (Table 3). Even when we removed the SNP representing the APOE locus, predictions remained positive (Supplementary Table S6). Yet the genetic correlation between our AD + P GWAS and Alzheimer’s disease, as estimated in LD HUB, was negative, although non-significant. Notably, PRSAD was built on results from a larger AD GWAS [42] than LD Hub uses [45]. Thus, we conjectured perhaps sample size explains the difference. However, when we computed PRSAD using the GWAS data from [45], it predicts AD + P as well as PRSAD from the larger GWAS, if not better (cf Supplementary Table S7 with Table 3) Notably, when we analyzed the genetic correlation of the two AD studies in LD Hub, the genetic correlation was 0.9 with standard error of 0.11. Thus, it seems likely that the difference between the genetic correlation estimated by LD HUB and the results for PRSAD trace to the genetic architecture of AD and differences in power for each method.

Because “uncorrelated” is not the same as “independent”, we evaluated one more dimension of these data. Specifically, we evaluated the GWAS-significant SNPs (GWAS SNPs) for schizophrenia [68], bipolar disorder [69], and AD [42] to determine whether they also had signal in our AD + P GWAS. We approached this question in two ways. First, we queried the GWAS SNPs to determine if their p values for AD + P were less than 10−4: Eleven SNPs crossed the threshold, all in the APOE locus and all associated with AD. Next, we reasoned that if some GWAS SNPs also generated risk for or protection from AD + P, whereas others did not, then those AD + P statistics would be represented by a mixture of distributions. We found support for a mixture of distributions for schizophrenia and separately for AD (Supplementary Fig. S6–S8), while for bipolar disorder there were too few independent GWAS SNPs to have any confidence in our results (See Supplementary Methods for details). Curiously, while AD GWAS SNPs were consistent in their effects on AD and AD + P, effects of schizophrenia GWAS SNPs were not. Instead, risk alleles for schizophrenia could impart risk or protection for AD + P (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Fig. S9). In addition, using the mixture model results, we identified a small set of SNPs likely to affect risk to AD + P and either AD or schizophrenia (Supplementary Table S8).

Discussion

We identified evidence of genome-wide significant association with psychosis risk in AD at SNPs within ENPP6, and in the 3′-UTR of an alternatively spliced transcript of SUMF1. Exploration of multiple data sets did not reveal any current evidence linking the SNPs at these loci to variation in expression of ENPP6, SUMF1, or other genes. Similarly, although the alternatively spliced SUMF1-204 transcript is expressed in brain [80], AD + P risk SNPs in the SUMF1 locus were not associated with brain expression of SUMF1-204 (S. Sieberts, Personal Communication). Nor were SNPs at these loci linked to other potential genetic mechanisms, such as variation in epigenetic modifications. However, we note that for SUMF1, the locus is in the 3′-UTR, a region that often serves a substantial role in regulating protein levels via post-transcriptional mechanisms [81].

ENPP6 encodes a glycerophosphodiesterase that is highly expressed in new oligodendrocytes as they differentiate from their precursors [82]. Recent data in mice have demonstrated that differentiation of oligodendrocytes from their precursors (as indicated by increased ENPP6 mRNA expression) is a necessary component of early [83], i.e. synaptic [84], phases of new (motor) learning. ENPP6 protein can be expressed both on the myelin membrane and as a soluble form that is found extracellularly [85, 86]. ENPP6 acts as a hydrolase that severs choline from substrates, including lysophosphatidylcholine, glycerophosphorylcholine, and sphingosylphosphorylcholine [86]. Of these, it has highest catalytic efficiency towards sphingosylphosphorylcholine [85], releasing both sphingosine and phosphocholine. Sphingosine is phosphorylated to generate sphingosine-1-phosphate, which signals via the g-protein-coupled sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor (S1PR1). It is of some interest, therefore, that the S1PR1 modulator, fingolimod [87], has been previously shown to increase excitatory synaptic transmission [88] and improve psychosis-associated behaviors in a genetic animal model of β-amyloid overproduction [89].

The locus on chromosome 3 maps to introns spanning the 3′-UTR of an alternatively spliced transcript of SUMF1. SUMF1 encodes formylglycine-generating enzyme, which serves as a master activator of lysosomal sulfatases by converting conserved cysteines to formylglycine in their active sites. As a consequence, genetic disruption of SUMF1 leads to a multiple sulfatase deficiency syndrome [90, 91]. Importantly, the transcript of SUMF1 (SUMF1-204, ENST00000448413.5), within which our locus is located, encodes an isoform of formylglycine-generating enzyme (isoform 3, Uniprot Accession Q8NBK3-3) lacking the enzymatically active Cys341 residue [92]. The functional consequences of this change are not established, but would be anticipated to reduce or eliminate the primary enzymatic function. The function of the novel sequence that replaces the c-terminal of formylglycine-generating enzyme in isoform 3 is also not known, and BLAST of this sequence against the UNIPROT database does not identify homologous proteins. Nevertheless, speaking to the potential functional impact in AD + P, ENST00000448413.5 is detectable in cerebral cortex [80].

Recently, an appreciation of how lysosomal storage dysfunction also leads to impaired autophagy has emerged [93]. It is not surprising, therefore, that selective depletion of SUMF1 in either astrocytes or neurons results in neurodegeneration [94]. How alterations in function of formylglycine-generating enzyme, due to a potential change in levels of isoform 3, may modify the course of AD through these mechanisms, and thus result in the AD + P phenotype, remains speculative. We have previously shown, however, that preservation of synaptic protein levels in the context of AD neuropathology is associated with reduced psychosis risk [89]. Thus, genetic alterations that impact degradation of synaptic proteins by the lysosome to autophagosome pathway are likely to influence risk of psychosis.

We and others [34] have previously evaluated the association of psychosis in AD with APOE risk haplotype ε4, finding inconsistent evidence of association [34]. Our current findings, obtained from by far the largest cohort to address this question, shed further light on these prior observations. We found that SNPs within APOE demonstrate gene-based significant association with AD + P, and that this association appears attributable to the presence of the ε4 haplotype itself, without a detectable contribution from other SNPs. Because the impact of ε4 on AD + P risk is not large, increasing the odds by 1.21, prior inconsistent associations with AD + P likely resulted from the much smaller sample sizes in all prior studies.

APOE ε4 has been shown to increase the accumulation of amyloid β and phosphorylated tau, and, even in the absence of Aβ overproduction, lead to reductions in dendritic markers and synaptic proteins [95]. For example, we have shown that human ε4 carriers and mice with targeted replacement of ε4 had down-regulation of numerous glutamate signaling and synaptic proteins [96]. Increased phosphotau and reduced synaptic proteins (but not altered amyloid β accumulation) have all been associated with psychosis in AD [97]. Future human and animal model studies of ε4 that control for the contribution of other loci to the genetic risk for AD + P would be helpful in determining the relative contributions of these mechanisms to AD + P.

We previously identified, and independently replicated, an inverse association between polygenic risk for schizophrenia, defined by a limited set of schizophrenia risk SNPs [79], and risk for psychosis in AD [28]. It was thus somewhat surprising that we saw a non-significant genetic correlation between these two disorders when considering both a larger set of SNPs and a substantially enlarged cohort of AD subjects with and without psychosis. Instead, we identified a negative genetic correlation with risk for bipolar disorder, a disorder that has substantial genetic overlap with schizophrenia. Because our prior analyses relied on a subset of SNPs significantly associated with risk for schizophrenia, and this set also shows enrichment for affecting risk for bipolar disorder (Supplementary Fig. S5), this overlap probably explains the discrepancy we now observe between our earlier results and the current results for genetic correlations. However, the lack of genetic correlation of AD + P with schizophrenia conceals an underlying complexity. We observed that schizophrenia risk SNPs evidenced significant mixture regarding AD + P risk, such that risk alleles for schizophrenia could impart risk or protection for AD + P.

In contrast, we observed a positive correlation between genetic risk for depressive symptoms and AD + P, consistent with clinical observations of co-occurrence of depressive and psychotic symptoms in AD patients [5, 13,14,15], and evidence that antidepressant medications may have some effect in reducing psychotic symptoms in AD [98, 99]. We also observed a significant negative genetic correlation of educational level with psychosis risk in AD, and a similar pattern, but not quite significant relationship with intelligence. Greater cognitive impairment increases the risk for psychosis in AD; moreover, psychosis in AD is further associated with a more rapid rate of cognitive decline [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] (see also review in [100]). The current findings extend these earlier observations, by showing genetic overlap with measures that may be better construed as indicative of cognitive reserve, as they reflect early life cognitive attainment. Cognitive reserve has long been recognized as protective against developing a degree of cognitive and functional impairment sufficient to lead to a diagnosis of AD [101]. However, somewhat counter-intuitively, once AD is diagnosed, individuals with greater cognitive reserve decline more rapidly [101]. Thus, the genetic correlations we observed may point to a biology underlying the presence of greater cognitive impairment in AD, but not the more rapid decline associated with AD + P.

The above findings are subject to several potential limitations. Although our analysis is the largest GWA study of AD + P to date, it is nevertheless modest in sample size in comparison to studies of related complex traits [78, 79]. As our heritability results show, a substantial increase in sample size will identify many additional loci as having a significant association with psychosis risk in AD. Similarly, increased sample size is needed to provide the necessary power to identify genes, transcripts, genetically correlated traits, and pathways in the corresponding analyses that derive from the SNP-based associations.

One of our GWAS-significant SNPs, rs201109606, falls in a genomic region marked as simple repeats. Perhaps because the SNP is difficult to impute, it did not pass QC for some of our data. Nonetheless, the largest two of the four datasets contribute to this result and the estimates of the odds ratios for the two data sets are remarkably similar, 0.684 and 0.637. Moreover, other SNPs at this locus also support the findings (Supplementary Table S1), although those associations are not quite GWAS significant. Thus, this result requires replication. For additional discussion of other findings and potential limitations, see Supplementary Material.

Currently established treatments for psychosis in AD patients are suboptimal, perhaps reflecting in part that these treatments were not derived to prevent or reverse an identified biology of AD + P [100]. The development of effective, specific, therapeutic targets will therefore require as a first step delineating this underlying biology. Our study provides the first unbiased evidence of association of specific genetic loci with psychosis in AD and can thus serve as an initial road map to AD + P biology. These findings, in conjunction with available functional genomic and post-mortem data, provide multiple links to mechanisms influencing synaptic function as contributors to psychosis in AD.

URLs

METAL http://csg.sph.umich.edu/abecasis/metal/index.html

GemTools http://www.compgen.pitt.edu/GemTools/GemTools.htm

PLINK https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2/

NCBI RS names https://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/snp/redesign/latest_release/VCF/

LD-Hub: http://ldsc.broadinstitute.org/LDHub/

Sanger Imputation Service: https://imputation.sanger.ac.uk

Psychiatric Genetics Consortium: https://www.med.unc.edu/pgc/

Imputation preparation: https://www.well.ox.ac.uk/~wrayner/tools/

CMC/AMP-AD eQTL Meta-analysis: https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn16984815

NCBI gene2go file: ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/DATA/

Reactome: https://reactome.org/download-data

Gene Ontology: http://geneontology.org/docs/download-ontology/

Molecular Signatures Database: https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp

R package qvalue: http://github.com/jdstorey/qvalue

LD Score Regression (LDSC) software v1.0.0: https://github.com/bulik/ldsc

HapMap 3 https://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/human/hapmap3.html

Common mind consortium: https://www.nimhgenetics.org/resources/commonmind

FUSION software http://gusevlab.org/projects/fusion/

References

Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Devlin B, Jeste DV. Psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer disease: evidence for a distinct phenotype. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:383–92.

Ropacki SA, Jeste DV. Epidemiology of and risk factors for psychosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 55 studies published from 1990 to 2003. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2022–30.

Weamer EA, Emanuel JE, Varon D, Miyahara S, Wilkosz PA, Lopez OL, et al. The relationship of excess cognitive impairment in MCI and early Alzheimer’s disease to the subsequent emergence of psychosis. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:78–85.

Emanuel JE, Lopez OL, Houck PR, Becker JT, Weamer EA, DeMichele-Sweet MA, et al. Trajectory of cognitive decline as a predictor of psychosis in early Alzheimer disease in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:160–8.

Sweet RA, Bennett DA, Graff-Radford NR, Mayeux R. Assessment and familial aggregation of psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease from the National Institute on Aging Late Onset Alzheimer’s Disease Family Study. Brain. 2010;133:1155–62.

Seltman HJ, Mitchell S, Sweet RA. A Bayesian model of psychosis symptom trajectory in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31:204–10.

Sweet RA, Seltman H, Emanuel JE, Lopez OL, Becker JT, Bis JC, et al. Effect of Alzheimer’s disease risk genes on trajectories of cognitive function in the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:954–62.

Koppel J, Sunday S, Goldberg TE, Davies P, Christen E, Greenwald BS. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease is associated with frontal metabolic impairment and accelerated decline in working memory: findings from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22:698–707.

Koppel J, Goldberg TE, Gordon ML, Huey E, Davies P, Keehlisen L, et al. Relationships between behavioral syndromes and cognitive domains in Alzheimer disease: the impact of mood and psychosis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20:994–1000.

Gilley DW, Whalen ME, Wilson RS, Bennett DA. Hallucinations and associated factors in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neuropsychiatry. 1991;3:371–6.

Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Beckett LA, Evans DA. Psychotic symptoms and physically aggressive behavior in Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:1074–9.

Sweet RA, Pollock BG, Sukonick DL, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, Klunk WE, et al. The 5-HTTPR polymorphism confers liability to a combined phenotype of psychotic and aggressive behavior in Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2001;13:401–9.

Wilkosz PA, Kodavali C, Weamer EA, Miyahara S, Lopez OL, Nimgaonkar VL, et al. Prediction of psychosis onset in Alzheimer disease: the role of depression symptom severity and the HTR2A T102C polymorphism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:1054–62.

Wilkosz PA, Miyahara S, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST, Sweet RA. Prediction of psychosis onset in Alzheimer disease: the role of cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and further evidence for psychosis subtypes. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:352–60.

Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JM, Steinberg M, Tschanz JA, Norton MC, Steffens DC, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease clusters into three groups: the Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1043–53.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, Masterman D, et al. Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: the neuropsychiatric inventory caregiver distress scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:210–5.

Rabins PV, Mace NL, Lucas MJ. The impact of dementia on the family. JAMA. 1982;248:333–5.

Lopez OL, Wisniewski SR, Becker JT, Boller F, DeKosky ST. Psychiatric medication and abnormal behavior as predictors of progression in probable Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:1266–72.

Magni E, Binetti G, Bianchetti A, Trabucchi M. Risk of mortality and institutionalization in demented patients with delusions. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1996;9:123–6.

Cummings JL, Diaz C, Levy M, Binetti G, Litvan II. Neuropsychiatric syndromes in neurodegenerative disease: frequency and signficance. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1996;1:241–7.

Bassiony MM, Steinberg M, Rosenblatt A, Baker A, Lyketsos CG. Delusions and hallucinations in Alzheimer’s disease: prevalence and clinical correlates. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:99–107.

Wilson RS, Tang Y, Aggarwal NT, Gilley DW, Mccann JJ, Bienias JL, et al. Hallucinations, cognitive decline, and death in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:68–75.

Bacanu SA, Devlin B, Chowdari KV, DeKosky ST, Nimgaonkar VL, Sweet RA. Heritability of psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Am J of Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:624–7.

Sweet RA, Nimgaonkar VL, Devlin B, Lopez OL, DeKosky ST. Increased familial risk of the psychotic phenotype of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2002;58:907–11.

Hollingworth P, Hamshere ML, Holmans PA, O’Donovan MC, Sims R, Powell J, et al. Increased familial risk and genomewide significant linkage for Alzheimer’s disease with psychosis. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:841–8.

Barral S, Vardarajan BN, Reyes-Dumeyer D, Faber KM, Bird TD, Tsuang D, et al. Genetic variants associated with susceptibility to psychosis in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease families. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:3116–3116.

Hollingworth P, Sweet R, Sims R, Harold D, Russo G, Abraham R, et al. Genome-wide association study of Alzheimer’s disease with psychotic symptoms. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:1316–27.

DeMichele-Sweet MAA, Weamer EA, Klei L, Vrana DT, Hollingshead DJ, Seltman HJ, et al. Genetic risk for schizophrenia and psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:963–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2017.81.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44.

Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86.

Seshadri S, Fitzpatrick AL, Ikram MA, DeStefano AL, Gudnason V, Boada M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic loci associated with Alzheimer disease. JAMA. 2010;303:1832–40.

Lambert MJ, Hatch DR, Kingston MD, Edwards BC. Zung, Beck, and Hamilton Rating Scales as measures of treatment outcome: A meta-analytic comparison. J. Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:54–9.

Moreno-Grau S, de Rojas I, Hernandez I, Quintela I, Montrreal L, Alegret M, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of dementia and its clinical endophenotypes reveal novel loci associated with Alzheimer’s disease and three causality networks: the GR@ACE project. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1333–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4950.

DeMichele-Sweet, MA, Lopez, OL & Sweet, RA. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease in the national Alzheimer’s disease coordinating center uniform data set: clinical correlates and association with apolipoprotein e. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;2011:926597. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/926597.

Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:311–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1312889.

Honig LS, Vellas B, Woodward M, Boada M, Bullock R, Borrie M, et al. Trial of Solanezumab for Mild Dementia Due to Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:321–30. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1705971.

Lovestone S, Francis P, Kloszewska I, Mecocci P, Simmons A, Soininen H, et al. AddNeuroMed-the European collaboration for the discovery of novel biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1180:36–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05064.x.

Roen I, Selbaek G, Kirkevold O, Engedal K, Testad I, Bergh S. Resourse Use and Disease Couse in dementia - Nursing Home (REDIC-NH), a longitudinal cohort study; design and patient characteristics at admission to Norwegian nursing homes. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:365. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2289-x.

Helvik AS, Engedal K, Saltyte Benth J, Selbaek G. Time from symptom debut to dementia assessment by the specialist healthcare service in Norway. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2018;8:117–27. https://doi.org/10.1159/000487233.

Eldholm RS, Barca ML, Persson K, Knapskog AB, Kersten H, Engedal K, et al. Progression of Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal study in norwegian memory clinics. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:1221–32. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-170436.

Bergh S, Holmen J, Gabin J, Stordal E, Fikseaunet A, Selbaek G, et al. Cohort profile: the Health and Memory Study (HMS): a dementia cohort linked to the HUNT study in Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:1759–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu007.

Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9.

DeMichele-Sweet MA, Klei L, Devlin B, Ferrell RE, Weamer EA, Emanuel JE, et al. No association of psychosis in Alzheimer disease with neurodegenerative pathway genes. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:555–511.

Weamer EA, DeMichele-Sweet MA, Cloonan YK, Lopez OL, Sweet RA. Incident Psychosis in subjects with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2016;77:e1564–e1569.

Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1452–8.

Tariot PN, Mack JL, Patterson MB, Edland SD, Weiner MF, Fillenbaum G, et al. The behavior rating scale for dementia of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1349–57.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12:233–9.

Boada M, Cejudo JC, Tarraga L, Lopez OL, Kaufer D. Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q): Spanish validation of a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric inventory (NPI). Neurologia. 2002;17:317–23.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The neuropsychiatric inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–14.

Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol. Rep. 1962;10:799–812.

Zubenko GS, Rosen J, Sweet RA, Mulsant BH, Rifai AH. Impact of psychiatric hospitalization on behavioral complications of Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:1484–91.

Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566–72.

Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98.

Bacanu SA, Devlin B, Chowdari KV, DeKosky ST, Nimgaonkar VL, Sweet RA. Linkage analysis of Alzheimer disease with psychosis. Neurology. 2002;59:118–20.

Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2190–1.

Creese B, Vassos E, Bergh S, Athanasiu L, Johar I, Rongve A, et al. Examining the association between genetic liability for schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9:273. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0592-5.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. https://doi.org/10.1086/519795.

Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience. 2015;4:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8.

Lee AB, Luca D, Klei L, Devlin B, Roeder K. Discovering genetic ancestry using spectral graph theory. Genet. Epidemiol. 2010;34:51–9.

Wang L, Zhang W, Li Q. AssocTests: an R package for genetic association. Studies. 2020;94:26. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v094.i05.

McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1279–83. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3643.

Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15393.

Loh PR, Danecek P, Palamara PF, Fuchsberger C, Y AR, H KF, et al. Reference-based phasing using the Haplotype Reference Consortium panel. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1443–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3679.

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: a tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.11.011.

Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh PR, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics, C. et al. LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2015;47:291–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3211.

Zheng J, Erzurumluoglu AM, Elsworth BL, Kemp JP, Howe L, Haycock PC, et al. LD Hub: a centralized database and web interface to perform LD score regression that maximizes the potential of summary level GWAS data for SNP heritability and genetic correlation analysis. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:272–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw613.

Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O’Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, et al. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009;460:748–52.

Pardinas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ, Escott-Price V, Ripke S, Carrera N, et al. Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50:381–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2.

Stahl EA, Breen G, Forstner AJ, McQuillin A, Ripke S, Trubetskoy V, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat Genet. 2019;51:793–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8.

de Leeuw CA, Mooij JM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. MAGMA: generalized gene-set analysis of GWAS data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2015;11:e1004219. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004219.

Network & Pathway Analysis Subgroup of Psychiatric Genomics, C Psychiatric genome-wide association study analyses implicate neuronal, immune and histone pathways. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:199–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3922.

de Leeuw CA, Neale BM, Heskes T, Posthuma D. The statistical properties of gene-set analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:353–64. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.29.

Gusev A, Ko A, Shi H, Bhatia G, Chung W, Penninx BW, et al. Integrative approaches for large-scale transcriptome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2016;48:245–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3506.

Consortium GT. The genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet. 2013;45:580–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2653.

Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004.

Kiezun A, Garimella K, Do R, Stitziel NO, Neale BM, McLaren PJ, et al. Exome sequencing and the genetic basis of complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44:623–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2303.

Devlin B, Risch N. A comparison of linkage disequilibrium measures for fine-scale mapping. Genomics. 1995;29:311–22. https://doi.org/10.1006/geno.1995.9003.

Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Abeta, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–30. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2.

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–7.

Gandal, MJ, Zhang, P, Hadjimichael, E, Walker, RL, Chen, C, Liu, S et al. Transcriptome-wide isoform-level dysregulation in ASD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Science. 2018;362, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat8127.

Tushev G, Glock C, Heumüller M, Biever A, Jovanovic M, Schuman EM. Alternative 3’ UTRs Modify the Localization, Regulatory Potential, Stability, and Plasticity of mRNAs in. Neuronal Compartments. Neuron. 2018;98:495–511.e496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.03.030.

Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, O’Keeffe S, et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34:11929–47. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1860-14.2014.

Xiao L, Ohayon D, McKenzie IA, Sinclair-Wilson A, Wright JL, Fudge AD, et al. Rapid production of new oligodendrocytes is required in the earliest stages of motor-skill learning. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1210–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4351.

Xu T, Yu X, Perlik AJ, Tobin WF, Zweig JA, Tennant K, et al. Rapid formation and selective stabilization of synapses for enduring motor memories. Nature. 2009;462:915–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08389.

Greiner-Tollersrud L, Berg T, Stensland HM, Evjen G, Greiner-Tollersrud OK. Bovine brain myelin glycerophosphocholine choline phosphodiesterase is an alkaline lysosphingomyelinase of the eNPP-family, regulated by lysosomal sorting. Neurochem Res. 2013;38:300–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-012-0921-z.

Sakagami H, Aoki J, Natori Y, Nishikawa K, Kakehi Y, Natori Y, et al. Biochemical and molecular characterization of a novel choline-specific glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase belonging to the nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23084–93. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M413438200.

Chun J, Brinkmann V. A mechanistically novel, first oral therapy for multiple sclerosis: the development of fingolimod (FTY720, Gilenya). Discov Med. 2011;12:213–28.

Darios FD, Jorgacevski J, Flasker A, Zorec R, Garcia-Martinez V, Villanueva J, et al. Sphingomimetic multiple sclerosis drug FTY720 activates vesicular synaptobrevin and augments neuroendocrine secretion. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5958. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05948-z.

Krivinko J, Erickson S, MacDonald M, Garver M, Sweet R. Fingolimod treatment rescues psychosis-associated behavioral aberrations in Appswe/Psen1de9 mice. The Am J of Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;26:S144–S145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2018.01.175.

Dierks T, Schmidt B, Borissenko LV, Peng J, Preusser A, Mariappan M, et al. Multiple sulfatase deficiency is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the human C(alpha)-formylglycine generating enzyme. Cell. 2003;113:435–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00347-7.

Cosma MP, Pepe S, Annunziata I, Newbold RF, Grompe M, Parenti G, et al. The multiple sulfatase deficiency gene encodes an essential and limiting factor for the activity of sulfatases. Cell. 2003;113:445–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00348-9.

Holder PG, Jones LC, Drake PM, Barfield RM, Banas S, de Hart GW, et al. Reconstitution of formylglycine-generating enzyme with copper(II) for aldehyde tag conversion. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:15730–45. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.652669.

Seranova E, Connolly KJ, Zatyka M, Rosenstock TR, Barrett T, Tuxworth RI, et al. Dysregulation of autophagy as a common mechanism in lysosomal storage diseases. Essays Biochem. 2017;61:733–49. https://doi.org/10.1042/EBC20170055.

Di Malta C, Fryer JD, Settembre C, Ballabio A. Astrocyte dysfunction triggers neurodegeneration in a lysosomal storage disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2334–2342. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1209577109.

Wolfe, CM, Fitz, NF, Nam, KN, Lefterov, I & Koldamova, R The Role of APOE and TREM2 in Alzheimer’s Disease-Current Understanding and Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20010081.

Sweet RA, Macdonald ML, Kirkwood CM, Ding Y, Schempf T, Jones-Laughner J, et al. Apolipoprotein E*4 (APOE*4) genotype is associated with altered levels of glutamate signaling proteins and synaptic coexpression networks in the prefrontal cortex in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:2252–62.

Krivinko JM, Erickson SL, Ding Y, Sun Z, Penzes P, MacDonald ML, et al. Synaptic proteome compensation and resilience to psychosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:999–1009. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17080858.

Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, Mazumdar S, Blakesley RE, Houck PR, et al. A double-blind comparison of citalopram and risperidone for the treatment of behavioral and psychotic symptoms associated with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:942–52.

Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, Sweet RA, Mazumdar S, Bharucha A, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of citalopram and perphenazine for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances associated with dementia. Am J of Psychiatry. 2002;159:460–5.

Murray PS, Kumar S, DeMichele-Sweet MA, Sweet RA. Psychosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:542–52.

Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:1006–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(12)70191-6.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the following federal grants: AG027224 (RAS), MH116046 (RAS), MH057881 (BD), AG030653 (MIK), AG041718 (MIK), AG066468 (OLL). Authors in the NIA-LOAD Family Based Study Consortium are Tatiana Foroud, M. Ilyas Kamboh, Oscar L. Lopez, and Richard Mayeux. Authors in the Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) are Tatiana Foroud, Richard Mayeux, and Robert A. Sweet. A complete list of contributing individuals, consortia, and their grant support can be found in Supplementary Acknowledgements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Each author is expected to have made substantial contributions: (1) to the conception or design of the work; RAS, BD, MIK, CB, OLL. (2) to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; MAAD-S, LK, BC, JCH, EAW, LM, RS, IH, SM-G, LT, MB, EA-M, SV, YL, BH, DA, GS, SB, AR, IS, HKS, BE, ES, OAA, SD, LA, DS, BB, DA, GF, PM, AS, DDR, AP, JW, RM, TF, AR, CB, PH, OLL, MIK, BD, RAS. (3) to the creation of new software used in the work; YL. (4) have drafted the manuscript or substantively revised it. MAAD-S, JCH, LK, BC, LM, CB, PH, MIK, BD, RAS. Each author has approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author’s contribution to the study) and has agreed both to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and to ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and the resolution documented in the literature.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

YL and BH are currently employed by and holding stock in Eli Lilly and Company. CB reports grants and personal fees from Acadia pharmaceutical company, grants and personal fees from Lundbeck, personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Otsuka, personal fees from Biogen, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from AARP, grants and personal fees from Synexus, personal fees from Exciva, outside the submitted work. OLL served as a consultant for Grifols, Inc. IS has been investigator in the drug trial Boehringer‐Ingelheim 1346.0023. OAA is a consultant to HEALTHLYTIX, speaker honoraria from Lundbeck. AS is or has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants unrelated to the present work from: Abbott, Abbvie, Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Clinical Data, Boheringer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Innovapharma, Italfarmaco, Janssen, Lundbeck, Naurex, Pfizer, Polifarma, Sanofi, Servier. MB is a consultant to GRIFOLS, BIOGEN, ROCHE, LILLY, CORTEXYME, ARACLON, MERCK. Grants La Caixa, IMI, ISCIII. DS reports personal fees from Biogen.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the NIA-LOAD Family Based Study Consortium and Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics Consortium (ADGC) are listed in Supplementary information.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DeMichele-Sweet, M.A.A., Klei, L., Creese, B. et al. Genome-wide association identifies the first risk loci for psychosis in Alzheimer disease. Mol Psychiatry 26, 5797–5811 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01152-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01152-8

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

The role of neurotransmitter receptors in antipsychotic medication efficacy for Alzheimer’s-related psychosis

The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery (2024)

-

Unique transcriptional signatures correlate with behavioral and psychological symptom domains in Alzheimer’s disease

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

-

Distinguishing features of depression in dementia from primary psychiatric disease

Discover Mental Health (2024)

-

Targeting the post-synaptic proteome has therapeutic potential for psychosis in Alzheimer Disease

Communications Biology (2023)

-

A global view of the genetic basis of Alzheimer disease

Nature Reviews Neurology (2023)