Abstract

There is paucity of evidence-based data on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). We performed a multicenter propensity-matched case-control study to compare HRQOL of newly diagnosed CML patients treated with front-line dasatinib (cases) or imatinib (controls). Patient-reported HRQOL was assessed with the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the EORTC QLQ-CML24 questionnaires. The impact on daily life scale of the EORTC QLQ-CML24 was selected a priori in the protocol as the primary HRQOL scale for the comparative analysis. Overall, 323 CML patients were enrolled of whom 223 in therapy with imatinib and 100 in therapy with dasatinib. Patients treated with dasatinib reported better disease-specific HRQOL outcomes in impact on daily life (Δ = 8.72, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.17–14.27, p = 0.002), satisfaction with social life (Δ = 13.45, 95% CI: 5.82–21.08, p = 0.001), and symptom burden (Δ = 7.69, 95% CI: 3.42–11.96, p = 0.001). Analysis by age groups showed that, in patients aged 60 years and over, differences favoring dasatinib were negligible across several cancer generic and disease-specific HRQOL domains. Our findings provide novel comparative HRQOL data that extends knowledge on safety and efficacy of these two TKIs and may help to facilitate first-line treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Imatinib, the first generation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has been introduced into clinical practice since 2001 laying the foundations for targeted therapies in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [1]. Clinical advances that have been made in this cancer area over the last two decades are outstanding, indeed life expectancy of these patients now approaches that of their peers from the general population [2].

After imatinib approval by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), other two TKIs, that is, dasatinib and nilotinib, were also approved for first-line use in CML, based on two pivotal randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [3, 4]. More recently, based on the results from another large RCT [5], also bosutinib has been approved as possible first-line treatment by the FDA.

Although these three newer approved TKIs have shown, to a different degree, higher and faster cytogenetic and molecular responses compared with imatinib, no major differences exist with regard to survival outcomes [6]. For example, long-term efficacy results of the phase III ENESTnd study indicated that 5-year estimated progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 92 and 91% and 94 and 92% for nilotinib (300 mg bid) and imatinib (400 mg bid), respectively [7]. Similarly, long-term results of the DASISION study indicated that 5-year estimated PFS and OS were 85 and 86% and 91 and 90% for dasatinib (100 mg qd) and imatinib (400 mg qd), respectively [8]. This scenario briefly illustrates why front-line treatment selection in newly diagnosed chronic phase (CP) CML patients has become one of the most critical challenges of patients’ management in routine practice [9].

Whilst there is substantial comparative data on efficacy and safety of newer TKIs versus imatinib as first-line therapy, no full paper comparing health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes has yet been published [10]. This lack of HRQOL data limits a full understanding of the potential advantages and disadvantages of currently available first-line treatment approaches. Indeed, the availability of comparative evidence-based information from the patient’s standpoint would further enhance physicians’ ability to make more informed treatment decisions.

Therefore, we performed a multicenter study to compare HRQOL profile of CP-CML patients treated with front-line imatinib or dasatinib therapy in real life. Secondary objectives were: to describe patient-reported symptom prevalence between treatment groups and examine HRQOL differences by age groups.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

This was an academic multicenter propensity-matched case-control study sponsored by the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA), which enrolled patients in Italy and Germany and involved 38 centers. Inclusion criteria included adult (≥18 years) patients with a diagnosis of Philadelphia chromosome positive and/or BCR-ABL positive CML confirmed by cytogenetic and/or molecular analysis and in first-line treatment with either dasatinib or imatinib for no more than 3 years. Also, patients had to be at least in complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) as documented by chromosome banding analysis of marrow cell metaphases or in major molecular response (≤0.1% BCR-ABL IS) at the time of study entry. Main exclusion criteria were: major cognitive deficits or psychiatric problems hampering a self-reported evaluation and having received any CML treatment prior to therapy with imatinib or dasatinib for more than three months.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committees of each participating center and all patients provided written informed consent. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02164903).

Study logistic

Eligible patients were approached in the hospital and invited to participate by their own treating physician. Investigators had to inform patients that possible non participation in this study would not have any consequence on their follow up care. All eligible patients were then explained the purpose of the study and those consenting were given a Survey Booklet, including a set of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) questionnaires, along with a self-addressed stamped envelope. Patients were requested to completing it at home, at their earliest convenience and returning them to an independent Data Center (i.e., GIMEMA Data Center in Italy). All clinical and laboratory information were taken from Hospital medical records and all data were then centrally collected and analyzed at GIMEMA Data Center. In case report forms, we also collected information on the availability of drugs in order to only include, in the main analysis, those patients for whom imatinib and dasatinib were equally available as treatment option at the time of diagnosis in the participating centers.

Patient-reported outcomes and a priori selection of primary scale for comparative analysis

The well validated cancer specific European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core30 (EORTC QLQ-C30) [11] and the recently developed EORTC QLQ-CML24 [12] were used to evaluate HRQOL and symptom burden. The QLQ-C30 consists of five functioning scales: physical, role, emotional, cognitive, and social; three symptom scales: fatigue, nausea/vomiting, and pain; six single-item scales: dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial impact; and the global health status/QoL scale. The items were scaled and scored using the recommended EORTC procedures [13].

The EORTC QLQ-CML24 was developed to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 [12] to comprehensively assess HRQOL in CML patients and its initial validation involved overall 655 CML patients in treatment with various TKIs from ten different countries (Europe, USA, and Asia) [12], and it is currently being further tested in another international study. This disease-specific questionnaire consists of the following six scales: impact on daily life, symptom burden, impact on worry/mood, body image problems, satisfaction with care and information, as well as satisfaction with social life. The impact on daily life scale was selected a priori in the research protocol as primary HRQOL scale for the comparative analysis, based on clinical grounds. Indeed, results from the development process of this questionnaire indicated that this scale was the most sensitive in reflecting differences in clinical response status and in performance status categories [12]. This scale consists of the following three items: (1) Have you had any difficulties carrying on with your usual activities because of getting tired easily? (2) How much has your treatment been a burden to you? (3) Have you needed social support (e.g., family, friends, or relatives) to undergo therapy or to cope with the disease?

Statistical analysis

We compared the mean scores of the impact of daily life scale (EORTC QLQ-CML24) [12] between CML patients treated with either dasatinib (cases) or imatinib (controls). To improve comparability between groups, cases and controls had been matched, before comparisons, on the estimated propensity scores by a 1:1 optimal pair matching [14]. The matching procedure included only those patients (n = 303) for whom both drugs were equally available as treatment option at the time of diagnosis. We estimated the propensity scores by a multivariable logistic model, based on the following key a priori selected variables measured at diagnosis: age (continuous), sex, living arrangements (living alone vs living with someone), comorbidity (yes vs no), ECOG performance status (0 vs ≥1), Sokal risk (low vs intermediate/high), and having received any previous treatment for CML (yes vs no). The prematching control group consisted of 206 imatinib patients and 97 subjects in the dasatinib group. Afterward, we obtained 94 matched case-control pairs performing an optimal nearest-neighbor matching. We assessed the postmatching balance between groups in all observed variables, by both computing the standardized mean differences (SMD) [15] and performing Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney tests [16, 17]. Based on previous work [18], for each variable we considered a postmatching SMD < 0.1 as an indicator of a good balance between groups. We further adjusted comparisons between matched groups by a linear mixed model performing a t-test for the null hypothesis of no difference between groups, including a treatment status indicator (dasatinib vs imatinib), education at study entry (low/compulsory school vs high) and months from treatment start [19]. We postulated these post-treatment variables as likely to have a potential impact on HRQOL outcomes but unlikely to have been affected by the type of drug [20]. We also performed the comparisons on the matched groups for all other HRQOL scales from both the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-CML24 questionnaires. Based on previous work [21], we also reported these adjusted comparisons separately for patients aged between 18 and 59 years or at least 60 years. In addition, we summarized individual symptoms from HRQOL questionnaires, as the proportions of patients reporting either any grade of or moderate to severe symptom severity. To this purpose, the continuous standardized scores (range 0–100) of multi-item symptoms from the EORTC QLQ-C30 were categorized as “not at all” if their score was 0 and “moderate to severe” if the score was at least 66 based on previous work [22]. For all other symptoms, severity was categorized as “not at all” and “moderate to severe” if the response to the single-item Likert scale was respectively “not at all” or “quite a bit/very much”. All statistical tests were two-sided at α = 0.05 level. Matching was performed using the MatchIt package in R software v.3.2.4 [23]. All analyses were performed by SAS software v 9.4. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between October 2014 and December 2016, 323 CML patients were enrolled but, for 11 patients, a HRQOL evaluation was not available. No statistically significant differences were found between patients with (n = 312) and without (n = 11) an HRQOL assessment with regard to key sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Details of patients included by treatment group and used in matching procedures are reported in Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patients’ enrollment and inclusion in primary analysis on propensity score-matched groups. aEleven patients did not return the HRQOL Survey Booklet to the Data Center but no statistically significant differences were found between these patients versus those who did (n = 312) with regard to key sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (data not shown)

After matching procedures, we achieved an optimal balance in all covariates used to estimate the propensity scores, each showing a postmatching SMD of <0.1 (Table 1). Mean age at diagnosis in both treatment groups was 58 years and 65 (69%) patients in both groups had an ECOG performance status of 0. There were 45 (48%) and 46 (49%) of patients having at least one comorbidity in the dasatinib and imatinib group, respectively. Patients’ characteristics, overall and by therapy, are reported in Table 1.

Disease-specific HRQOL differences between imatinib and dasatinib therapy

We found a statistically significant difference in the prespecified primary HRQOL scale between the two propensity score-matched groups. Patients treated with dasatinib reported a statistically significant lower mean score on the impact on daily life scale being 18.82 (SD, 19.98), compared with those treated with imatinib who reported a mean score of 26.22 (SD, 23.29) (Δ = 8.72, 95% confidence interval [CI] of 3.17 and 14.27, p = 0.002).

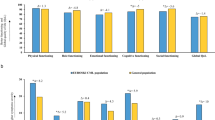

Analysis of other CML specific HRQOL outcomes, showed further statistically significant differences with regard to satisfaction with social life (Δ = 13.45, 95% CI of 5.82 and 21.08, p = 0.001) and symptom burden (Δ = 7.69, 95% CI of 3.42 and 11.96, p = 0.001) which favored patients treated with dasatinib compared those treated with imatinib. The estimated mean score differences between the two groups for all HRQOL scales of the EORTC QLQ-CML24 questionnaire are displayed in Fig. 2.

EORTC QLQ-CML24 scores and adjusted mean differences (95% CIs) between dasatinib and imatinib therapy. SD standard deviation. Imatinib and dasatinib patients had been previously matched on the propensity scores estimated on characteristics at diagnosis, i.e., age, sex, living arrangement, comorbidity, ECOG performance status, Sokal risk, and previous treatment for CML. Comparisons were further adjusted by education (low vs high) and months from treatment start. A higher score represents a higher burden in impact on daily life, symptom burden, impact on worry mood, and body image problems. To ease readability, mean adjusted differences of these scales were presented in the graph as multiplied by −1. In satisfaction scales, a higher score represents a higher level of satisfaction

Cancer generic HRQOL differences between imatinib and dasatinib therapy

Statistically significant differences favoring patients treated with dasatinib were found for: cognitive functioning (Δ = 5.76, 95% CI of 0.24 and 11.28, p = 0.041), social functioning (Δ = 8.10, 95% CI of 1.91 and 14.30, p = 0.011), pain (Δ = 8.77, 95% CI of 2.60 and 14.95, p = 0.006), nausea/vomiting (Δ = 4.97, 95% CI of 0.66 and 9.29, p = 0.024) and diarrhea (Δ = 9.42, 95% CI of 2.35 and 16.49, p = 0.009). However, patients treated with dasatinib reported statistically significant worse problems of constipation (Δ = −7.43, 95% CI of −14.28 and −0.57, p = 0.034) compared with the patients treated with imatinib. No significant differences were found in other scales. The estimated mean score differences by type of therapy of all scales of the EORTC QLQ-C30 are depicted in Fig. 3.

EORTC QLQ-C30 scores and adjusted mean differences (95% CIs) between dasatinib and imatinib therapy. EORTC European Organization for Research and treatment of Cancer, QLQ Quality of Life Questionnaire, SD standard deviation. Imatinib and dasatinib patients had been previously matched on the propensity scores estimated on characteristics at diagnosis, i.e., age, sex, living arrangement, comorbidity, ECOG performance status, Sokal risk, and previous treatment for CML. Comparisons were further adjusted by education (low vs high) and months from treatment start. In functional scales a higher score represents a better health status, while in symptom scales a higher score represents a worse symptom problem. To ease readability, mean adjusted differences of symptoms scales were presented in the graph as multiplied by −1

Patient-reported symptom prevalence by type of therapy

The prevalence of fatigue (i.e., with any level of concern) was similar between groups being reported by 78 (83%) and 74 (79%) patients treated with dasatinib and imatinib, respectively. In the imatinib group, there were more than one-fifth of patients who reported eight symptoms as moderate to severe. Conversely, in the dasatinib group, only one symptom (i.e., aches or pains in muscles or joints) was reported as moderate to severe by just one-fifth of patients. Further details on patient-reported symptom prevalence for the two propensity score-matched groups are reported in Table 2.

Treatment difference by age groups (18–59 vs 60 years or older)

Further analyses examining mean score differences between patients treated with dasatinib versus those treated with imatinib, indicated that differences were larger in patients aged between 18 and 59 years compared to those aged 60 years or older across all HRQOL domains. With regard to symptom aspects, the burden of dyspnea was markedly different by age, with younger patients reporting better outcomes with dasatinib therapy (Δ = 8.58) and older patients reporting better outcomes with imatinib therapy (Δ = −7.99). Regardless of age, problems of constipation were worse for patients treated with dasatinib (Fig. 4c). Further details on patterns of HRQOL mean differences by the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the QLQ-CML-24 questionnaires by age group categories are reported in Fig. 4.

Health-related quality of life adjusted mean differences between dasatinib and imatinib therapy by age groups. EORTC European Organization for Research and treatment of Cancer, QLQ Quality of Life Questionnaire. Imatinib and dasatinib patients had been previously matched on the propensity scores estimated on characteristics at diagnosis, i.e., age, sex, living arrangement, comorbidity, ECOG performance status, Sokal risk, and previous treatment for CML. Comparisons were further adjusted by education (low vs high) and months from treatment start. A higher score represents a higher burden in impact on daily life, symptom burden, impact on worry/mood and body image problems from EORTC QLQ-CML24 and in EORTC QLQ-C30 symptoms. To ease readability, mean adjusted differences of these scales were presented in the graph as multiplied by −1. A higher score in functional scales from EORTC QLQ-C30 represents a better health status. In satisfaction scales of EORTC QLQ-CML24, a higher score represents a higher level of satisfaction

Discussion

We found that CML patients treated with first-line dasatinib, who were able to reach at least a CCyR, report a significantly lower impact of therapy on their daily life compared to their peers treated with imatinib.

Our analysis of individual symptoms, indicated that patients treated with dasatinib, not only reported a lower prevalence (with any level of concern) of many symptoms compared to patients treated with imatinib, but also that this difference was often larger than that documented by previous physician-reported adverse events (AEs) [8, 24]. For example, muscle cramps were reported by 66 (70%) and 28 (30%) patients treated with imatinib and dasatinib, respectively. However, it is important to note that the prevalence of fatigue, which is a key symptom for CML patients [25, 26] was similar between the two groups, and constipation was markedly less prevalent in patients treated with imatinib. Inspection of prevalence of moderate to severe symptoms indicated a substantial burden of therapy in both groups, but prevalence was still broadly lower for patients treated with dasatinib. Our analysis also revealed differences with regard to new specific treatment-related symptoms and problems that were not previously documented in AEs reporting [27]. These included: problems of frequent urination, acid indigestion or heartburn, dry mouth, constipation, and excessive sweating.

Although regulatory stakeholders consider HRQOL and other PROs as key aspects to determine clinical benefit of new drugs [28], very little is known with regard to the different impact of various TKIs on patient’s wellbeing [10]. Unfortunately, out of all the pivotal RCTs that led to the approval of currently available front-line TKIs, full HRQOL results were only reported for the IRIS Study, which compared imatinib versus interferon therapy [29, 30]. To the best of our knowledge, the only comparison of HRQOL outcomes between imatinib and dasatinib therapy was presented in an abstract form by Labeit and colleagues in 2015, indicating no HRQOL differences between treatment arms [31]. However, it is difficult to compare their data [31] with our results, as a number of information regarding the methodology used to assess HRQOL are not available being an abstract. While several reasons could explain the difference with our findings, it is plausible that one relates to HRQOL questionnaires used. Labeit et al. [31] used a set of HRQOL questionnaires that were not specifically validated in CML patients receiving TKIs, therefore possibly limiting the sensitivity to capture important symptoms or health domains for this population. In our study, we used the EORTC QLQ-CML24 that was specifically developed in a large international sample of CML patients, thus ensuring a high content validity of relevant health concerns for this population [12]. In the current CML arena, it is likely that only PRO questionnaires specifically developed for this population may best capture differences across various TKIs.

Another finding emerged from the propensity-matched HRQOL comparisons, performed by age group categories. We found that younger patients (18–59 years) typically reported larger HRQOL differences favoring dasatinib therapy, with respect to older patients (≥60 years). Notably, differences favoring dasatinib in older patients were negligible across several key HRQOL aspects, including: body image problems, role functioning, and fatigue severity. This finding has important clinical implication as it suggests that younger CML patients are those who may benefit the most from dasatinib therapy, at least in some specific HRQOL domains. Previous reports in CML patients treated with imatinib [21] showed that older patients (≥60 years) have a similar HRQOL profile than that of their peers from the general population and this might partially explain our finding.

This study has limitations. As this is not a RCT, we could not account for possible bias in treatment assignment due to unobserved variables at diagnosis. Also, given the cross-sectional design, we could not speculate whether HRQOL differences favoring patients treated with dasatinib found in some key domains, persist over the long-term period and, therefore, prospective comparative HRQOL studies are needed. Indeed, further research is warranted to confirm our findings.

This study also has key strengths. Our propensity score matching approach, allowed the comparison of two optimally balanced patient groups in terms of key clinical and sociodemographic characteristics. Also, we provide the first HRQOL comprehensive analysis and evidence-based data on the impact of two first-line TKIs from the patients’ standpoint, therefore facilitating a more patient-centered treatment decision-making approach. Indeed, main currently available comparative data between imatinib and dasatinib therapy stem from laboratory-based and clinician-reported information.

In conclusion, current findings indicate that newly diagnosed CML patients at least in CCyR treated with front-line dasatinib, broadly report better disease-specific HRQOL outcomes compared to their peers treated with imatinib therapy. However, in patients aged 60 years and over, differences favoring dasatinib were negligible across several HRQOL domains. Our HRQOL results extend current knowledge on safety and efficacy data of dasatinib versus imatinib and can help both patients and physicians to make more informed treatment decisions.

References

Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, Radich JP, Branford S, Hughes TP, et al. Long-term outcomes of imatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:917–27.

Bower H, Bjorkholm M, Dickman PW, Hoglund M, Lambert PC, Andersson TM. Life expectancy of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia approaches the life expectancy of the general population. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2851–7.

Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, le Coutre P, Etienne G, Lobo C, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2251–9.

Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, Cortes J, Shah S, Ayala M, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2260–70.

Cortes JE, Gambacorti-Passerini C, Deininger MW, Mauro MJ, Chuah C, Kim DW, et al. Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: results from the randomized BFORE trial. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:231–7.

Rosti G, Castagnetti F, Gugliotta G, Baccarani M. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic myeloid leukaemia: which, when, for whom? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:141–54.

Hochhaus A, Saglio G, Hughes TP, Larson RA, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Long-term benefits and risks of frontline nilotinib vs imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: 5-year update of the randomized ENESTnd trial. Leukemia. 2016;30:1044–54.

Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, Baccarani M, Mayer J, Boque C, et al. Final 5-year study results of DASISION: the dasatinib versus imatinib study in treatment-naive chronic myeloid leukemia patients trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2333–40.

Shah NP. Front-line treatment options for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:220–4.

Efficace F, Cannella L. The value of quality of life assessment in chronic myeloid leukemia patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2016;2016:170–9.

Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365–76.

Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Saussele S, Abel G, Caocci G, et al. International development of an EORTC questionnaire for assessing health-related quality of life in chronic myeloid leukemia patients: the EORTC QLQ-CML24. Qual Life Res. 2014;23:825–36.

Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, on behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. The EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001.

Rosenbaum P, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. Constructing a control group using multivariate matched sampling methods that incorporate the propensity score. Am Stat. 1985;39:33–8.

Pooler JA, Srinivasan M. Association between supplemental nutrition assistance program participation and cost-related medication nonadherence among older adults with diabetes. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:63–70.

Kwon IG, Son T, Kim HI, Hyung WJ. Fluorescent lymphography-guided lymphadenectomy during robotic radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:150–8.

Nguyen TL, Collins GS, Spence J, Daures JP, Devereaux PJ, Landais P, et al. Double-adjustment in propensity score matching analysis: choosing a threshold for considering residual imbalance. BMC Med Res Method. 2017;17:78.

Cottone F, Anota A, Bonnetain F, Collins GS, Efficace F. Propensity score methods and regression adjustment for analysis of nonrandomized studies with health-related quality of life outcomes. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2019;28:690–9.

Rosenbaum PR. The consquences of adjustment for a concomitant variable that has been affected by the treatment. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1984;147:656–66.

Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Alimena G, Rosti G, Cottone F, et al. Health-related quality of life in chronic myeloid leukemia patients receiving long-term therapy with imatinib compared with the general population. Blood. 2011;118:4554–60.

Johnsen AT, Tholstrup D, Petersen MA, Pedersen L, Groenvold M. Health related quality of life in a nationally representative sample of haematological patients. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83:139–48.

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. J Stat Softw. 2011;42:1–28.

Kantarjian HM, Shah NP, Cortes JE, Baccarani M, Agarwal MB, Undurraga MS, et al. Dasatinib or imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: 2-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood. 2012;119:1123–9.

Phillips KM, Pinilla-Ibarz J, Sotomayor E, Lee MR, Jim HS, Small BJ, et al. Quality of life outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a controlled comparison. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21:1097–103.

Efficace F, Baccarani M, Breccia M, Cottone F, Alimena G, Deliliers GL, et al. Chronic fatigue is the most important factor limiting health-related quality of life of chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with imatinib. Leukemia. 2013;27:1511–9.

Radich JP, Deininger M, Abboud CN, Altman JK, Berman E, Bhatia R, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia, Version 1.2019, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Cancer Netw. 2018;16:1108–35.

Kluetz PG, O’Connor DJ, Soltys K. Incorporating the patient experience into regulatory decision making in the USA, Europe, and Canada. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e267–74.

O’Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, Gathmann I, Baccarani M, Cervantes F, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:994–1004.

Hahn EA, Glendenning GA, Sorensen MV, Hudgens SA, Druker BJ, Guilhot F, et al. Quality of life in patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia on imatinib versus interferon alfa plus low-dose cytarabine: results from the IRIS Study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2138–46.

Labeit AM, Copland M, Cork LM, Hedgley CA, Foroni L, Osborne WL, et al. Assessment of quality of life in the NCRI spirit 2 study comparing imatinib with dasatinib in patients with newly-diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukaemia. Blood. 2015;126:4024.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study. We also acknowledge Giora Sharf and Felice Bombaci from the CML Advocates Network for their help in the initial setting up of the study.

Funding

This study was supported in part by the Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS). BMS had no role in the design and conduct of this study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data presented; and preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: FE, FC, GR. Data analysis and interpretation: All authors. Statistical analysis: FC, FE. Manuscript writing: All authors. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

FE: Consultancy: BMS, Amgen, Orsenix, Incyte and Takeda. MBr: Honoraria: Novartis, BMS, Pfizer, Incyte, Celgene. MBo: Research funding: Novartis; Consultancy: Bristol Myers Squibb. FCa: Consultancy: Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Incyte; Honoraria: Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Incyte. MC: Honoraria: Incyte, Novartis, Celgene, Amgen. AP: Research funding: Novartis. SS: Research funding: Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte; Honoraria: Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Incyte, Pfizer. GB: Honoraria: Incyte, Pfizer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis. GR: Honoraria: Novartis, Bristol Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Incyte. MV: Consultancy and Advisory board: Jazz Healthcare, Millennium Pharmaceuticals. Educational meeting: Pfizer

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Efficace, F., Stagno, F., Iurlo, A. et al. Health-related quality of life of newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with first-line dasatinib versus imatinib therapy. Leukemia 34, 488–498 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0563-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-019-0563-0

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

A Comprehensive Overview on Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Insights into the Underlying Inflammatory and Oxidative Mechanisms

Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy (2024)

-

A predictive scoring system for therapy-failure in persons with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving initial imatinib therapy

Leukemia (2022)

-

Real-life comparison of nilotinib versus dasatinib as second-line therapy in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients

Annals of Hematology (2021)

-

Health state utility and quality of life measures in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in France

Quality of Life Research (2021)

-

Health-Related Quality of Life of Patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia as Measured by Patient-Reported Outcomes: Current State and Future Directions

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2021)