Abstract

The aim of this study was to find the association between adherence to the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations (NNR) and glucose metabolism. Participants were 137 pregnant obese women or women with a history of gestational diabetes (GDM) from the Finnish Gestational Diabetes Prevention Study. Adherence to the NNR was assessed by the Healthy Food Intake Index (HFII) calculated from the first trimesters’ food frequency questionnaires. Higher HFII scores reflected higher adherence to the NNR (score range 0−17). Regression models with linear contrasts served for the main analysis. The mean HFII score was 10.0 (s.d. 2.8). The odds for GDM decreased toward the higher HFII categories (P=0.067). Fasting glucose (FG) and 2hG concentrations showed inverse linearity across the HFII categories (P(FG)=0.030 and P(2hG)=0.028, adjusted for body mass index, age and GDM/pregnancy history). Low adherence to the NNR is associated with higher antenatal FG and 2hG concentrations and possibly GDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Accumulating evidence suggests an association between non-optimal diet and gestational diabetes (GDM). Approached by dietary indices, lower risk of GDM has been associated with alternate Mediterranean diet score (aMed), Diet Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) and alternate Healthy Eating Index (aHEI).1 We recently showed that the Healthy Food Intake Index (HFII) can be used without detailed dietary data or energy adjustment for ranking the participants according to their adherence to the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations (NNR).2 The purpose of the present study was to assess whether adherence to the NNR at early pregnancy is associated with lower risk of GDM and better glucose metabolism at second trimester.

The participants were part of the Finnish Gestational Diabetes Prevention Study, a lifestyle intervention study in two Southern Finnish districts taking place between 2008 and 2014.3 In total, 496 Finnish obese (body mass index (BMI)⩾30 kg/m2) women, or women with a history of GDM were recruited. They were either ⩽20 weeks pregnant (n=293) or planning pregnancy (n=203). Exclusion criteria were age<18 years, overt diabetes diagnosed before pregnancy, medication affecting glucose metabolism, physical disability, multiple pregnancy, severe psychiatric disorder, current substance abuse and substantial communication difficulties. In order to exclude any interference by the lifestyle intervention, the present study included participants in the control arm (n=236, in the total RADIEL population). Only participants with normal 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) at the first trimester of pregnancy were included. Of the women recruited and randomized to the control group before pregnancy, 37 (38%) did not become pregnant, and 19 (19%) were excluded owing to pathologic first trimester OGTT. Among all control women, loss to follow-up was 7 (3%), miscarriage dropped was 9 (4%), second trimester OGTT was missing for 13 (5.5%) and dietary data were missing for 14 (6%) participants. The final number of participants was 137 (58% of the participants in the control arm). This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving human subjects were approved by The Ethics Committee of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. All participants provided written informed consent.

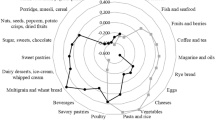

The dietary data were collected at the first trimester of pregnancy by a food frequency questionnaire. The HFII comprised the following components: snacks, low-fat cheese, fish, low-fat milk, vegetables, fruits and berries, sugar-sweetened beverages, high-fiber grains, fast food, fat spread and cooking fat.2 The highest score reflects highest adherence to the NNR. Background data were collected by questionnaires. Weight and height were measured at the first visit to the study nurse during pregnancy, and weight additionally at second trimester visit. The 75 g OGTTs were conducted at 6−18 weeks, and, if normal, the participants were included in the present study. The OGTTs were repeated at gestational weeks 24−28. One pathological value led to GDM diagnosis (thresholds: fasting plasma glucose (FG) ⩾5.3 mmol/l, 1-h ⩾10.0 mmol/l and 2-h glucose concentration (2hG) ⩾8.6 mmol/l).

The HFII scores were divided into three categories by setting zcut-off limits at ±1 standard deviation from the mean. Trends across the HFII categories were tested by one-way analysis of variance, Cochran-Armitage trend test, Cuzick’s trend test or general linear models with planned linear contrasts. The differences between the GDM-affected and non-affected groups were tested by two-tailed Student’s t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test or Pearson chi-square test. The associations between continuous HFII and glucose metabolism were studied by logistic regression and general linear models. Model 2 was adjusted for the following risk factors: BMI, age and GDM/pregnancy history,4 and Model 3 additionally for educational attainment, which may reflect differences in health status.5 Normality of the variables was tested by Shapiro–Wilk test, and equality of variance by Levene’s test. Stata 13.1, StataCorp LP (College Station, TX, USA) statistical package, was used for the analyses.

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. The mean HFII of the participants was 10.0 (s.d. 2.8). The incidence of GDM from lowest to highest category was 7 (29%), 18 (21%) and 4 (14%; P=0.39). The odds for GDM decreased toward the higher categories of the HFII (non-significant; Table 2). FG and 2hG concentrations across the HFII categories showed significant inverse linearity (adjusted for BMI, age and GDM/pregnancy history). Adjustment for educational attainment resulted in loss of significance for FG but not for 2hG. Models including leisure-time physical activity and weight gain showed no impact on the estimates (results not shown).

The present study suggests that high scores in the HFII, that is, high adherence to the NNR, may be associated with lower FG and post glucose load 2hG. The effect estimates of the HFII-GDM association were similar to the findings reported on GDM’s association with aMed, DASH and aHEI.1 The lack of statistical significance of the HFII-GDM association may have resulted from the small sample size. Previous similar studies have been larger.1 The significant associations of the HFII with FG and 2hG suggest that adherence to the NNR could be a determinant for GDM risk in Nordic countries. This is supported by data-driven dietary pattern analysis where dietary patterns high in fruits and vegetables, and low in meat, snacks and sweets are associated with lower risk of GDM.6

Possible mediating factor could be fruits and vegetables replacing red and processed meat or other harmful foods.7 Constituents of fruits, berries and vegetables may also affect glucose metabolism, and oppose free radicals and inflammation.8

We cannot exclude the possibility that diet during pregnancy was a reflection of pre-pregnancy diet,9 or poor reliability of self-reported physical activity.10 As a strength, the HFII was thoroughly validated for the present purpose.2 In addition, controlling for absent GDM diagnosis at first trimester confirmed GDM over unrecognized type 2 diabetes. That and confirming that diet preceded GDM diagnosis excluded the possibility of reverse causality. The results give ground for a larger study to confirm the association between the NNR and GDM.

References

Tobias DK, Zhang C, Chavarro J, Bowers K, Rich-Edwards J, Rosner B et al. Prepregnancy adherence to dietary patterns and lower risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 96: 289–295.

Meinila J, Valkama A, Koivusalo SB, Stach-Lempinen B, Lindstrom J, Kautiainen H et al. Healthy Food Intake Index (HFII) - Validity and reproducibility in a gestational-diabetes-risk population. BMC Public Health 2016; 16: 680.

Koivusalo SB, Rono K, Klemetti MM, Roine RP, Lindstrom J, Erkkola M et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus can be prevented by lifestyle intervention: The Finnish Gestational Diabetes Prevention Study (RADIEL). A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2016; 39: 24–30.

Teh WT, Teede HJ, Paul E, Harrison CL, Wallace EM, Allan C . Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus: implications for the application of screening guidelines. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011; 51: 26–30.

Mari-Dell'Olmo M, Gotsens M, Palencia L, Burstrom B, Corman D, Costa G et al. Socioeconomic inequalities in cause-specific mortality in 15 European cities. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015; 69: 432–441.

Schoenaker DA, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Callaway LK, Mishra GD . Pre-pregnancy dietary patterns and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: results from an Australian population-based prospective cohort study. Diabetologia 2015; 58: 2726–2735.

Aune D, Ursin G, Veierod MB . Meat consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Diabetologia 2009; 52: 2277–2287.

Hamer M, Chida Y . Intake of fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 2007; 25: 2361–2369.

Crozier SR, Robinson SM, Godfrey KM, Cooper C, Inskip HM . Women's dietary patterns change little from before to during pregnancy. J Nutr 2009; 139: 1956–1963.

Evenson KR, Chasan-Taber L, Symons Downs D, Pearce EE . Review of self-reported physical activity assessments for pregnancy: summary of the evidence for validity and reliability. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2012; 26: 479–494.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the women who participated in the study, the study nurses, research dietitians, and research scientists who contributed to this study. This work was supported by the Ahokas Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Disease, Special State Subsidy for Health Science Research of Helsinki University Central Hospital, Samfundet Folkhälsan, The Finnish Diabetes Research Foundation, Foundation for Medical Research Liv och Hälsa, Kulturfonden, Juho Vainio Foundation, State Provincial Office of Southern Finland and The Social Insurance Institution of Finland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meinila, J., Valkama, A., Koivusalo, S. et al. Association between diet quality measured by the Healthy Food Intake Index and later risk of gestational diabetes—a secondary analysis of the RADIEL trial. Eur J Clin Nutr 71, 555–557 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.275

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.275

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Exploration of Diet Quality by Obesity Severity in Association with Gestational Weight Gain and Distal Gut Microbiota in Pregnant African American Women: Opportunities for Intervention

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2022)

-

Association of rs10830962 polymorphism with gestational diabetes mellitus risk in a Chinese population

Scientific Reports (2019)