Abstract

Background

Subarachnoid hemorrhage has been traditionally ruled-out in the emergency department (ED) through computed tomography (CT) followed by lumbar puncture if indicated. Mounting evidence suggests that non-contrast CT with CT angiography (CTA) can safely rule-out subarachnoid hemorrhage and obviate the need for lumbar puncture, but adoption of this approach is hindered by concerns of identifying incidental aneurysms. This study aims to estimate the incidence of incidental aneurysms identified on CTA head and neck in an ED population.

Methods

This was a health records review of all patients ≥ 18 years who underwent CTA head and neck for any indication at four large urban tertiary care EDs over a 3 month period. Patients were excluded if they underwent CT venogram only, had previously documented intracranial aneurysms, or had intracranial hemorrhage with or without aneurysm. Imaging reports were reviewed by two independent physicians before extracting relevant demographic (age, sex), clinical (CTAS level, CEDIS primary complaint) and radiographic (number, size, and location of aneurysms) information. The incidence rate of incidental aneurysms was calculated.

Results

A total of 1089 CTA studies were reviewed with a 3.3% (95% CI 2.3–4.6) incidence of incidental intracranial aneurysms. The median size of incidental aneurysms was 4 mm (0.7–11) and 10 (27.7%) patients had multiple aneurysms. Patients with incidental aneurysms did not differ based on mean age, sex, and CTAS levels.

Conclusions

The “risk” of discovering an incidental aneurysm is 3.3%. Clinicians should not be deterred from using CTA in the appropriate clinical settings. These estimates can inform shared decision-making conversations with patients when comparing subarachnoid hemorrhage rule-out options.

Résumé

Contexte

L'hémorragie sous-arachnoïdienne (HSA) a été traditionnellement exclue au service des urgences (SU) par tomodensitométrie cérébrale (TDM) suivie d'une ponction lombaire si indiquée. Des preuves de plus en plus nombreuses suggèrent que la tomographie sans contraste avec l'angiographie par tomodensitométrie (l'angio-TDM) permet d'exclure en toute sécurité les HSA et d'éviter la ponction lombaire, mais l'adoption de cette approche est entravée par les craintes d'identifier des anévrismes accidentels. Cette étude vise à estimer l'incidence des anévrismes accidentels identifiés par l'angiographie de la tête et du cou dans une population d'urgences.

Méthodes

Il s’agissait d'une étude des dossiers médicaux de tous les patients âgés de ≥ 18 ans qui ont subi une angioplastie de la tête et du cou, quelle qu'en soit l'indication, dans quatre grands services d'urgence urbains de soins tertiaires sur une période de trois mois. Les patients étaient exclus s'ils n'avaient subi qu'une phlébographie par tomodensitométrie, s'ils avaient déjà eu des anévrismes intracrâniens documentés ou s'ils avaient eu une hémorragie intracrânienne avec ou sans anévrisme. Les rapports d’imagerie ont été examinés par deux médecins indépendants avant d’extraire les informations démographiques pertinentes (âge, sexe), cliniques (niveau CTAS, plainte primaire CEDIS) et radiographiques (nombre, taille et emplacement des anévrismes). Le taux d’incidence des anévrismes accidentels a été calculé.

Résultats

Un total de 1089 études angio-TDM ont été examinées avec une incidence de 3,3 % (IC à 95 % : 2,3-4,6) d'anévrismes intracrâniens accidentels. La taille médiane des anévrismes fortuits était de 4 mm (plage : 0,7-11) et 10 (27,7 %) patients présentaient des anévrismes multiples. Les patients présentant des anévrismes accidentels ne différaient pas en fonction de l'âge moyen, du sexe et des niveaux CTAS.

Conclusions

Le « risque » de découvrir un anévrisme fortuit est de 3,3 %. Les cliniciens ne doivent pas être dissuadés d'utiliser l'angio-TDM dans les contextes cliniques appropriés. Ces estimations peuvent éclairer les conversations de prise de décision partagée avec les patients lors de la comparaison des options d'exclusion de l'HSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What is known about the topic? |

The incidence of intracranial aneurysms identified on CT angiography (CTA) in an ED population is clinically important and currently unknown. |

What did this study ask? |

What is the rate of newly identified incidental intracranial aneurysms in an undifferentiated ED population undergoing head and neck CTA? |

What did this study find? |

This health records review found a 3.3% incidence of newly diagnosed incidental intracranial aneurysms on CTA. |

Why does this study matter to clinicians? |

New incidental intracranial aneurysms are infrequently identified on CTA and should not deter clinicians from using this useful clinical tool. |

Background

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is an established tool with several clinical indications in the emergency department (ED) including evaluation of suspected stroke syndromes [1].

The current established practice of investigating suspected subarachnoid hemorrhage consists of a non-contrast CT Head for patients presenting within 6 h of symptom onset [2, 3] with subsequent lumbar puncture (LP) if time to presentation is greater than 6 h. However, LP’s have drawbacks including ED physician time, patient pain, technical difficulty, rare but serious complications, and diagnostic uncertainty even when completed [4]. Recent evidence has emerged promoting the potential utility of CTA as a part of a rule-out strategy for subarachnoid hemorrhage which would eliminate the aforementioned challenges [5].

A barrier to CT + CTA implementation cited by emergency physicians is a concern of detecting incidental asymptomatic aneurysms unrelated to the patient’s presentation [5]. This may be driven by awareness of the risks associated with interventions resulting from the discovery of a new and possibly inconsequential aneurysm. However, notwithstanding the fact that any aneurysm detected incidentally is at risk of subsequent rupture [6], the background rate of aneurysms in an ED population is likely overestimated. Unfortunately, the published data on the background rate of aneurysms is based largely on cadaveric studies, invasive angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) and therefore may not reflect the true incidence of incidental aneurysms that would be identified through CTA [7]. Furthermore, none of the studies on the incidence of incidental aneurysm on CTA have been specific to an ED population. The objective of this study was to fill this gap by estimating the incidence of incidental aneurysms identified on CTA head and neck in an ED population. Demonstrating a low incidence of incidental intracranial aneurysms may mitigate the concerns of emergency physicians and facilitate the clinical uptake of the CT + CTA strategy for investigating subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Methods

This was a health records review of all patients who underwent CTA head and neck for any indication between August 1st, 2019 and October 30th, 2019 at four large urban tertiary care hospitals in Calgary, Alberta, including the regional stroke referral center. This study was approved by the Calgary Health Research Ethics Board.

Population

The study population included all patients aged ≥ 18 years presenting to the ED with a complaint that resulted in them undergoing a CTA head and neck. Canadian Emergency Department Information System (CEDIS) presenting complaints included, but were not limited to symptoms of stroke, headache, dizziness, confusion, extremity weakness, and altered level of consciousness. Patients were excluded if they only had CT venogram, had previously documented aneurysms, had hemorrhage with or without identifiable aneurysm, or if they had missing CTA data.

Data extraction

A comprehensive search of the universal electronic medical record was conducted to identify all patients meeting inclusion and exclusion criteria who underwent CTA head and neck over the study period. Two independent emergency physician reviewers (BS, GB) then manually analyzed the relevant radiology reports read by staff radiologists to assess for the primary outcome. Charts were analyzed for demographic and clinical information including sex, age, Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) level and CEDIS presenting complaint. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus mediated by a third independent emergency physician (CW).

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was defined as the presence of newly diagnosed unruptured incidental intracranial aneurysm(s) identified by radiologist interpretation of arterial phase, contrast-enhanced CTA of the head and neck. To avoid misclassification of aneurysms as ‘incidental’, this label was only given following manual chart review of all relevant clinical documents from initial visit to the end of the study period to ensure no subsequent diagnoses or presentations occurred due to the identified aneurysm. Secondary outcomes included the number, size, and anatomic location(s) of the aneurysm(s).

Statistical analysis

Based on available evidence, the baseline prevalence of incidental intracranial aneurysm was estimated at 2% [6]. A sample size calculation determined that for a desired precision of 1% and a corresponding 95% confidence interval, we required a sample size of 1064 patients. Patients were compared across clinically relevant characteristics using two-sample t test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test with continuity correction for categorical variables (statistical significance level of α = 0.05). The incidence proportion of identified incidental intracranial aneurysms was calculated as the number of radiologic reports identifying aneurysms divided by the total number of analyzed reports. All 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were determined using the Clopper–Pearson method for exact binomial confidence intervals. Statistical analyses were completed using R version 4.0.0 (www.r-project.org) with the addition of the ‘tableone’ and ‘Desctools’ packages.

Results

A total of 1240 CTA head and neck studies were completed during the study period. The predominant reasons for exclusion were patients only undergoing CT venogram (n = 46) or because they had hemorrhage with or without an associated aneurysm (n = 86). Following exclusions, 1089 CTA head and neck studies were included in the analysis. The study cohort was 52.1% female with a mean age of 64.6 years (SD = 16.9). Patients presented with all CTAS levels with the large majority (80.1%) having CTAS 2 or 3. There were 57 unique CEDIS primary complaints leading to CTA with the most common being “symptoms of stroke” (34.0%) followed by “dizziness” (12.2%). Patients with an incidental intracranial aneurysm did not differ from those without on age, sex or CTAS level. The only difference was in CEDIS presenting complaint, with any statistically significant differences likely driven by small differences across many primary complaint categories. Further information on the cohort stratified by incidental intracranial aneurysm status can be found on Table 1.

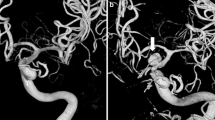

We identified 36 incidental intracranial aneurysms resulting in an incidence proportion of 3.3% (95% CI 2.3–4.6). 10 (27.8%) of the patients had multiple aneurysms (1–4). Locations of the identified aneurysms varied with 23 located in the internal carotid artery, 9 in the middle cerebral artery and 8 in the anterior cerebral artery. The median size of the incidental aneurysms was 4 mm (0.7–11.0).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to estimate the incidence of incidental intracranial aneurysms in ED patients undergoing CTA head and neck. We determined that incidental aneurysms were identified in 3.3% (95% CI 2.3–4.6) of patients. Individuals with incidental aneurysms did not differ from patients without in age, sex or acuity.

The incidence proportion of 3.3% identified in our analysis of an ED population is well aligned with previous studies in other groups looking at the prevalence of intracranial aneurysm [7].

The main limitation of this study is that the population studied was not specific to the population of clinical interest, namely patients presenting with severe headaches. We would have been unable to obtain adequate statistical power by limiting the search to the CEDIS complaint of “headache”, although the aneurysm incidence in this subpopulation in our study (3/108; 2.8%) was comparable to our overall finding. The number of CTAs performed for “headache” that are extractable on a chart review are limited, given established guidelines do not recommend CTA for headaches. A prospective, randomized trial would therefore be necessary to capture this population.

Limitations inherent to the clinical utility of CTA is that CTAs are not available at all centres, and that the sensitivity of CTA decreases for intracranial aneurysms < 4 mm in size [8].

Furthermore, the longer-term clinical relevance (i.e., whether they present acutely later) of the finding of supposedly incidental aneurysms on CTA in the ED remain unknown and warrants further study.

The clinical utility of our findings is contingent on a high diagnostic accuracy of a CT + CTA strategy for the rule-out of subarachnoid hemorrhage, as well as the safety profile compared to the alternative CT + LP strategy. Multiple studies have concluded that a negative non-contrast CT followed by a negative CTA rules-out subarachnoid hemorrhage with a post-test probability of < 1% [9]. From a safety perspective, complications related to CTA are very rare and relatively benign, typically related to acute kidney injury or allergic reaction [5]. While complications of LP are also uncommon, qualitative studies show that patient acceptability of this procedure is low [10], giving more reason to explore the less invasive CT + CTA diagnostic approach.

In conclusion, we determined that incidental intracranial aneurysms are identified in 3.3% of all ED patients being investigated with CTA head and neck. This finding combined with an equivalent diagnostic accuracy for subarachnoid hemorrhage and a higher acceptability among patients suggest that a CT + CTA strategy for ruling-out subarachnoid hemorrhage may be a safe, fast, and non-invasive alternative to the traditional CT + LP strategy. These findings may also expand diagnostic options for patients presenting beyond the 6 h window required to use non-contrast CT alone. At minimum, this information can be presented to patients in a shared decision-making conversation guided by their values and preferences.

References

Mayer SA, Viarasilpa T, Panyavachiraporn N, et al. CTA-for-all. Stroke. 2020;51:331–4. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.027356.

Blok KM, Rinkel GJE, Majoie CBLM, et al. CT within 6 hours of headache onset to rule out subarachnoid hemorrhage in nonacademic hospitals. Neurology. 2015;84:1927–32. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001562.

Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti MLA, et al. Sensitivity of computed tomography performed within six hours of onset of headache for diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343: d4277. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4277.

Migdal VL, Wu WK, Long D, et al. Risk-benefit analysis of lumbar puncture to evaluate for nontraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage in adult ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1597-1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.06.048

Probst MA, Hoffman JR. Computed tomography angiography of the head is a reasonable next test after a negative noncontrast head computed tomography result in the emergency department evaluation of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:773–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.009.

Hurford R, Taveira I, Kuker W, et al. Prevalence, predictors and prognosis of incidental intracranial aneurysms in patients with suspected TIA and minor stroke: a population-based study and systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:542–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2020-324418.

Vlak MH, Algra A, Brandenburg R, et al. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysms, with emphasis on sex, age, comorbidity, country, and time period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011;10:626-636. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(11)70109-0

McKinney AM, Palmer CS, Truwit CL, et al. Detection of aneurysms by 64-section multidetector CT angiography in patients acutely suspected of having an intracranial aneurysm and comparison with digital subtraction and 3D rotational angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2008;29:594–602. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0848.

Meurer WJ, Walsh B, Vilke GM, et al. Clinical guidelines for the emergency department evaluation of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Emerg Med 2016;50:696–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.07.048.

Scotton WJ, Mollan SP, Walters T, et al. Characterising the patient experience of diagnostic lumbar puncture in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a cross-sectional online survey. BMJ Open. 2018;8: e020445. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020445.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, C.K.H., O’Rielly, C.M., Sheppard, B. et al. The emergency department incidence of incidental intracranial aneurysm on computed tomography angiography (EPIC-ACT) study. Can J Emerg Med 24, 268–272 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00267-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43678-022-00267-3