Abstract

Prior work on the sources of public punitiveness and the expansion of the penal state emphasizes the importance of various anxieties associated with late modernity. Specifically, theorists posit that the expansion of neoliberal policies has been attended by animus against marginalized social groups, anxieties about economic and social conditions, and fear of crime—public sentiments which have legitimized the expansion of a penal apparatus that has undermined democracy. In the present study, we extend the traditional focus on punitiveness to include support for authoritarian forms of state power. Using of cross-national survey data (n = 13,071) from 16 Latin American countries collected during a period of democratization and the region’s “punitive turn,” we find that the social sensibilities from late modernity also drive support for autocratic forms of government. Further, our analyses reveal an indirect association between these attitudes and authoritarianism that operates through punitiveness. Our findings also suggest a “democracy paradox.” Examining country-level moderating factors, we find that these associations are more salient in countries with higher levels of democratization and social inclusion, which are thus particularly vulnerable to the democracy-eroding pressures of “governing through crime.” We discuss the implications of these findings for Latin America as well as democracies in the Global North.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The punitiveness literature has documented the myriad social changes that contributed to the expansion of the penal stateFootnote 1 (Alexander, 2010; Beckett, 1997; Enns, 2016; Garland, 2001; Simon, 2007; Wacquant, 2009, 2010). Although there are differences in how researchers have portrayed the punitive turn that began in latter portion of the twentieth century, scholars generally agree that public punitiveness played an important role in the “get tough” era by driving and legitimizing the adoption of punitive approaches to crime control (Beckett, 1997; Enns, 2016; Frost, 2010). While this literature originated in the Global North to explain social processes occurring in the U.S. and Europe, it has more recently been used to describe changes occurring across the Global South (Carrington et al., 2016; Garland, 2005; Sozzo, 2016, 2017a).

Scholars have examined the many ways in which the penal state, a mode of governance centered in crime control, undermines democracy. First, felony disenfranchisement laws that directly remove electoral rights from large portions of the population have consequences that reach beyond those disenfranchised, reducing political participation and fostering legal estrangement among marginalized communities (Alexander, 2010; Bell, 2020; Clear, 2007; White, 2019). Second, as Simon (2020, p. 60) notes, the mandate of individual responsibility and the excluding logics of “governing through crime” creates support for policies that undermine the “infrastructure of democracy.” Defunding welfare and education and legitimizing regressive tax policies that expand inequality changes the balance of democracy, concentrating wealth and power among the “overclass” (Beckett & Western, 2001; Wacquant, 2010). Moreover, the broad public support for the expansion of state control, punishment, and even the discretionary power of state actors attests to the democratic character of this mode of governance. Indeed, Enns (2016) describes the process through which politicians respond to public sentiments regarding crime and punishment by enacting punitive policies as “democracy at work.”

A large body of scholarly work has been focused on understanding the main drivers of punitive sentiments. Garland’s (2001) conceptualization of the “culture of control” describes punitive sentiments as stemming from the anxieties of late modernity, including crime, victimization, and a conservative response to broader social transformations. Relatedly, Wacquant (2009) explains the punitive turn as an attempt to govern and control a racialized urban marginality, in a context of expansion of neoliberal market-based policies that increase economic insecurity, inequality, job instability, and animosity towards racialized and marginalized groups (see also Alexander, 2010; Beckett, 1997; Bobo & Thompson, 2010; Simon, 2007). A common theme in these explanations is the renewed emphasis on a culture of personal responsibility that blames the poor and marginalized for their own fate and constructs poverty as a moral and individual failure. This erosion of social solidarities conjunctly legitimated the rise of the penal state and the retraction of the welfare state, the latter of which not only was severely undercut but was reframed and subsumed within the logic of surveillance and punishment characteristic of the penal state (Beckett & Western, 2001; Garland, 2001; Wacquant, 2010).

Although the literature depicts the expansion of the penal apparatus and the “punitive turn” as originating in the Global North, scholars have acknowledged both the interconnectedness of social changes in a globalized world and the importance of country-level variation. An emerging line of research focuses on identifying commonalities between larger social changes—such as those from late modernity or the expansion of neoliberalism—and punitive orientations across the world. Historical traditions, social structures, and the institutions that shape larger social policies (e.g., the welfare state and labor regulations) are connected to specific penal policies and explain important cross-national differences in the quantity and quality of punishment (Garland, 2005, 2018; Lacey, 2013; Tonry, 2007; Wacquant, 2009). Still, as Carrington et al. (2016) argue, Global North narratives have failed to consider the penal and political configurations occurring within the Global South, and thus do not provide comprehensive frameworks that help to better understand penal policies across the world.

In this paper, we analyze data from sixteen countries in Latin America to explore the mechanisms through which the penal state may constrain democracy and foster authoritarianism. This region arguably has faced a democratization paradox in which the social changes brought by consolidating democracies may have fostered the conditions for their demise, fueling support for punitive approaches to control crime and broader authoritarian actions from the state. Accordingly, we conceptualize punitive attitudes as the lower end of a gradient of repressive forms of state power ranging from support for harsher penalties to support for several forms of autocratic power, including an “iron fist” government, military involvement in domestic security, an authoritarian leadership, the president’s closing of the supreme court or congress, and a military coup. Thus, in this study, we examine whether the sources of public punitiveness identified in the Global North literature explain support for the expansion of the criminal control apparatus as well as for repressive use of state power and autocratic forms of government in this region. Further, we examine how the salience of these features varies across Latin American countries to determine whether democratization itself makes these pressures more prominent.

The Social Sources of Public Punitiveness

While the “punitive turn” which led to unparalleled levels of state control was paramount in the U.S., most Western industrialized countries also embraced more punitive approaches to crime control (Garland, 2018; Tonry, 2007; Wacquant, 2009). In light of these trends, the sociology of punishment literature has focused on the consequences of the consolidation of the penal state and how it undermines democracy. Perhaps the most direct effect of this “democratic contraction” concerns the removal of voting rights from an increasing number of individuals processed through the criminal justice system (Uggen & Manza, 2002; see also Dhami, 2005; Uggen et al., 2009, 2020). Felony disenfranchisement—and criminal justice contact more broadly—has broader spillover effects, fostering legal estrangement within the communities to which prisoners return and undermining collective action and community organization (Alexander, 2010; Bell, 2020; Clear, 2007; Michener, 2019; White, 2019). A second, more indirect mechanism through which the expansion of the penal apparatus affects democracy is the penetration of the penal logic into other spheres of public life, including the retraction of the welfare state and its reformulation into a system of surveillance and punishment. This new governmental approach furthered the stigmatization and marginalization of the (racialized) poor and legitimized the expansion of neoliberal policies that undermine the “infrastructure of democracy” (Beckett & Western, 2001; Wacquant, 2010).

Within this context of justice system expansion and concomitant democratic contraction, a vast amount of research has examined potential social sources of “penal populism” (Roberts et al., 2002) among members of the public (e.g., Beckett & Sasson, 2003; Cullen et al., 2000; Frost, 2010; Pickett, 2019; Ramirez, 2013; Unnever & Cullen, 2010b). One key pattern emerging from this body of work is that support for harsh criminal justice policy has been conflated with the neoliberal “war against the poor” (Beckett & Western, 2001; Piven, 2015; Simon, 2020; Wacquant, 2010). Indeed, the penal state was expanded over several decades with the clear goal of “not only hiding away criminal offenders, but also removing from sight those who challenge American ideals of individualistic achievement and prosperity” (Brown & Socia, 2017, p. 938). Accordingly, previous research has revealed a negative association between punitive sentiments and both support for welfare (Hogan et al., 2005; Pickett et al., 2013; Rubin, 2011) and egalitarian beliefs (Brown & Socia, 2017; Kornhauser, 2015; Unnever et al., 2008).

Some of the strongest correlates of punitive sentiments include racialized conceptions of crime, perceived economic competition with minoritized groups, and other dimensions of racial/ethnic resentment. Indeed, an extensive body of work revealed that anti-minority attitudes are associated with increased support for harsh sentences (e.g., Baker et al., 2018; Chiricos et al., 2004; Johnson, 2001; Lehmann et al., 2020; Unnever & Cullen, 2007, 2010a, 2012), punitive forms of juvenile justice (Metcalfe et al., 2015; Pickett & Chiricos, 2012), and strict enforcement of immigration policies (Buckler et al., 2009; Pickett, 2016; Stupi et al., 2016). Beyond animus against marginalized groups, however, there also is an anticipated theoretical connection between anti-LGBTQ and sexist attitudes and punitiveness. According to the “moral decline model,” one of its primary functions of punishment is to set “the tolerable moral limits of a society” (Unnever & Cullen, 2010b, p. 104) in order to shore up moral boundaries and strengthen social solidarity, especially when there is a shared sense that core institutions are under attack (Brown & Socia, 2017; Tyler & Boeckmann, 1997). These processes are likely to be especially salient in late modernity, as household and workplace structures become more precarious, increasing vulnerability and insecurity (Garland, 2001; Beckett, 2020).

A related line of inquiry focuses on economic anxieties, which can become conflated with feelings of anger and bitterness against social groups perceived as receiving “special treatment” via government financial assistance (Garland, 2001; Wacquant, 2010b). In the context of late modern societies where individualistic ideologies prevail and blame for crime and other social ills can be displaced onto marginalized groups, “diffuse anxieties” surrounding personal and societal economic conditions can fuel punitiveness (Costelloe et al., 2009; Hogan et al., 2005; Lehmann & Pickett, 2017; Ousey & Unnever, 2012). Finally, some prior research has found that fear of crime is associated with heightened punitive sentiments (e.g., Costelloe et al., 2009; Dowler, 2003; Kleck & Jackson, 2017; Singer et al., 2020; Sprott & Doob, 1997; Unnever et al., 2005). According to Unnever and Cullen (2010b), there is “a pervasive and deeply felt sense that anyone could be the next victim of the ever-escalating increase in criminality” but that “the welfare state no longer can be trusted to put victims’ interests ahead of offenders’ interests” (p. 103). Thus, like economic anxiety, fear of crime represents a key facet of neoliberal democracies, and “government through crime” strategies are engaged to placate public anxieties while simultaneously expressing authoritarian control (Garland, 2001; Simon, 2007).

Democratization and the Bottom-Up Erosion of Democracy

Despite this large body of work uncovering the drivers of public punitiveness itself, little attention has been paid to the potential role of the public in legitimizing increasingly authoritarian forms of state power. Scholars largely agree that the transformation of the penal apparatus was sustained and legitimized by the increasing punitive demands from the public—a sensibility that Garland (2001) terms the “culture of control” (Beckett, 1997; Enns, 2016; Frost, 2010; Hall, 1978; Simon, 2007, 2020). Although it remains unclear whether public opinion was a main driver of punishment policies (Enns, 2016) or whether the public was a manipulated recipient of fears induced by the media and political elites to gain legitimacy and advance their agendas (Beckett, 1997, 2020; Hall, 1978), scholars generally understand the dynamic between public opinion and punitive policies as entrenched within the functioning of liberal democracies. According to Simon (2020), the broad public support for “governing through crime” demonstrates its compatibility with democratic functioning; moreover, these public pressures are idiosyncratic of democratic societies where bottom-up pressures become relevant. Thus, the “culture of control” sensibilities represent a response to the democratization and individualization of social life brought by late modernity and the rejection of social welfarism it encompasses (Garland, 2001).

While this literature on the “punitive turn” has provided important insights into the social sources of public punitiveness, it remains unclear whether these patterns are expected to be universal or, instead, emerge only within specific societal configurations, that is, Western industrialized democracies. In the Spanish edition of his book The Culture of Control, Garland (2005, p. 20) broadens the scope of the impact of these changes and describes them as a global phenomenon:

The United States and Great Britain are not alone in regard to the development of new ways to respond to the risks and insecurities encompassed by the individualized freedoms of late modernity, even when they can differentiate themselves in regard to the penal solutions that they seek to impose. Mass incarceration and a generalized culture of control is a type of response to the problems of social order of this era.Footnote 2

In this article, we explore whether the social sensibilities that, according to the narratives from the Global North, configured this new culture of control and were instrumental in the expansion of the penal state also constitute sources of punitiveness in Latin America. Our study also seeks to expand on this literature by highlighting the potential broader consequences of the consolidation of the social sensibilities of the “culture of control” in triggering a bottom-up erosion of democracy. Thus, our study examines whether research on public punitiveness can indeed provide insights to understand the global democratic recession observed in recent years.

As Lührmann and Lindberg (2019) posit, the world seems to be immersed in a third wave of autocratization, driven not by regime changes but rather by generalized and subtle forms of democratic recession (see also V-Dem, 2021). Seeking keys to understand the bottom-up processes of democratic erosion across Europe, Norris and Inglehart (2019) theorize them to be the product of a “cultural backlash” in which authoritarian populist leaders capitalize on and reinforce an “authoritarian reflex” that emerges as a response to the sharp cultural changes brought by late modernity. This defensive response embraced by a weaning but still sizable portion of the population promotes a rhetoric of fear that privileges the collective security of a group deemed to be under attack. The policy solutions rely on and a way of governing that limits the autonomy and freedom of groups seen as morally and culturally threatening (immigrants, racialized minorities, LGBTQ + individuals) and privileges order and security over individual freedom. Importantly, the advent of a populist authoritarianism agenda not only poses a threat to even the most functioning democracies, but it is also produced precisely by the democratic advances made by liberal democracies.

Democratic Expansion and the Penal State in Latin America

Currently, Latin American countries seem to be leading the process of democratic recession observed across the world, and the challenges to the once-praised democratization processes are becoming increasingly apparent (EIU, 2020; Latinobarómetro, 2021; Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018; Lührmann & Lindberg, 2019; Pérez-Liñán et al., 2019). By the turn of the twenty-first century, most Latin American countries were transitioning from authoritarian regimes to relatively stable liberal and further consolidating democracies (Garretón, 2003; Iturralde, 2016; Kurtenbach, 2019; Weyland, 2004). Thus, Latin American experiences provided insight into the construction of democratic states and allowed for comparative research on the maintenance and functioning of democracies across the world. However, many of the democratization processes in Latin American countries have remained incomplete, characterized by relatively weak institutions, state dependency, unfulfilled economic and social achievements, and high levels of social exclusion (Garretón, 2003; Hilgers & MacDonald, 2017; Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2018; Weyland, 2004). Further, recent trends reveal a weakening public support for democracy and increasing levels of acceptance of a wide range of autocratic forms of government (military coups, authoritarian leaders, government control of media, etc.) in the region (Latinobarómetro, 2021; Zechmeister & Lupu, 2019).

Enduring high levels of violence have been a major challenge for Latin American democracies throughout their democratization process (Kurtenbach, 2019). According to Müller (2018, p. 172), there was a “qualitative shift from the supposedly ‘old,’ political violence of the military dictatorships towards a ‘new,’ predominantly criminal form of violence.” Further, the expansion of neoliberalism and market-based policies that constrained the welfare state undercut the infrastructure of democracy and concentrated power among the rich, thereby consolidating a penal state that exerted violence towards and further marginalized the racialized poor (Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2012; Pearce, 2010; Swanson, 2013; Wacquant, 2003). The punitive turn was especially harsh in Latin America—a region characterized by “democracies without citizenship” (Iturralde, 2016) with already weak welfare states and high levels of inequality and social exclusion. Müller (2012) notes that the intersection between neoliberal reforms and the democratization process bolstered “governing through crime” in the region and facilitated the rise of penal populism, as a tough approach to crime was viewed as needed.

Sozzo (2016, 2017b) questions the applicability of the “neoliberal penality thesis” to the South American context by showing how incarceration rates continued to rise even in countries that entered a post-neoliberal era (see also Carrington et al., 2016; Lacey, 2013). To different degrees, post-neoliberal governments enacted a series of reforms that advanced social inclusion, increased the role of the state in the economy, enhanced the political participation and mobilization of marginalized populations, and helped to consolidate the democratization process. Despite their relative levels of success in halting the advance of neoliberalism in the region, they were unable to consistently scale back an already occurring punitive turn and, in some cases, even intensified it (de Azevedo & Cifali, 2017; Grajales & Hernández, 2017; Paladines, 2017; Sozzo, 2017b). Reflecting on these processes, Sozzo (2016, 2017a) is wary of global explanations of punitive changes that diffuse local variations, and he highlights the need to better understanding the institutional arrangements and political struggles that shape the penal field and make global processes relevant in specific contexts (see also Garland, 2018).

Public preoccupation about crime has been identified as a key factor driving and legitimizing the consolidation of the penal state in Latin America (Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2012, 2018; Wacquant, 2003). Public opinion surveys have also been illustrative of these processes, showing that the public places insecurity and crime among the most important national problems and as threats to future development (Hilgers & MacDonald, 2017; Sozzo, 2016). In line with findings from industrialized countries, studies of Latin America support the idea that the problem of crime and insecurity impacts attitudes towards criminal justice institutions and engenders support for more punishment for criminals (Singer et al., 2019; Bergman et al., 2008; Dammert & Salazar, 2009; Fernandez & Kuenzi, 2009). Some of this research also has addressed how this climate of insecurity influences regime legitimacy in incomplete democracies and fosters support for authoritarianism (Carreras, 2013; Hilgers & MacDonald, 2017; Iturralde, 2016; Malone, 2010; Pearce, 2010; Zechmeister, 2014). Thus, the expansion of “governing through crime” in Latin America may have political consequences that are substantially broader than increased public punitiveness (Müller, 2018). In fact, Sozzo (2017a, 2017b) acknowledges that bottom-up punitive waves operate as constraints to the political viability of a progressive crime control agenda, which is rendered unsustainable and too politically risky to governments that have exhausted their political capital.

The Current Study

This study explores the parallels between the emergence of the culture of control that led to the expansion of a populist punitive agenda and the more recent growth of authoritarian populism. We examine these processes in Latin America—a region that, at the time the data for this study were collected, was on a path of both democratic consolidation and penal expansion. Specifically, in this study, we explore whether the social sensibilities that are associated with increased support for punitive policies and have been identified as responsible for the configuration of the “culture of control” also drive public support for autocratic forms of government. In this scenario, the consolidation of the penal state would not only undermine democracy from the top down—by excluding large portions of the population from full citizenship and exerting an authoritarian and unequal use of state violence against marginalized populations—but would also be responsible for generating the social conditions that legitimize the progressive autocratization of democratic regimes from the bottom up. Thus, we assess the existence of a potential “democratization paradox” in the region, where the “culture of control” is byproduct of democratization itself and the opportunities it created for the development of a defensive authoritarian and punitive populist agenda that panders to the fears of the electorate.

Based on the previous literature on the topic, we hypothesize that the advances in democratization will intensify the direct and indirect association between the sources of public of public punitiveness described above—anti-welfare attitudes, racist views, anti-progressive attitudes, economic anxiety, and fear of crime—and support for a wide set of autocratic modes of government—an iron fist government, the militarization of security, an authoritarian leader, the closing of democratic institutions, and a military coup.

Data and Methods

This study uses data from the 2012 AmericasBarometer survey, a biennial survey collected in North, Central, and South American and Caribbean countries by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP). Respondents are representative of the non-institutionalized voting-age population of each country, and face-to-face interviews are conducted with one individual per household. The 2012 AmericasBarometer survey was administered to 41,632 respondents in 26 countries in the Americas; however, due to inconsistencies in the questionnaires across countries, only respondents from sixteen countries from Latin America (i.e., Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela) in which all relevant survey items were included are assessed (n = 13,071).

Country-level data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset from 2012 (Coppedge et al., 2021a, 2021b) are also included. These data provide a comprehensive set of more than 350 indicators measuring different aspects of democratic functioning in 177 countries. The V-Dem project seeks to advance a nuanced conceptualization of democracy that goes beyond democracy linked to elections. For that reason, they conceptualize six different “high-level principles of democracy,” collecting indicators that measure each of these principles: electoral, liberal, participatory, deliberative, egalitarian, majoritarian, and consensual democracy (Coppedge et al., 2021c). We also use 2012 data from the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The descriptive statistics for the study variables are presented in Table 1.

Dependent Variables

There are six dependent variables in this study that represent support for a variety of forms of state power, from harsh laws to autocratic forms of government. Each variable was made dichotomous for ease of comparison across outcomes. Support for harsher penalties was measured according to respondents’ agreement with the statement, “The best way to fight crime is to be tougher on criminals” (0 = somewhat or strongly disagree, 1 = somewhat agree or strongly agree). The second dependent variable, support for an iron fist government, was measured with the question, “Do you think that our country needs a government with an iron fist, or do you think that problems can be resolved with everyone’s participation?” (0 = “everyone’s participation,” 1 = “iron fist”). Support for military security was based on agreement with the statement, “The Armed Forces ought to participate in combatting crime and violence” (0 = disagree, 1 = agree).

Willingness to close institutions is also a dichotomous variable that measures support for the president of the country either closing the Congress/Parliament or dissolving the Supreme Court/Constitutional Tribunal and governing without them when the country is facing difficult times, or support for both (= 1). Support for authoritarian leader is coded according to reporting either “We need a strong leader who does not have to be elected” (= 1) or “Electoral democracy is the best” (= 0). Finally, supporting a military coup is measured based on agreement with several items. Those who indicated that a military take-over of the state would be justified when there is (1) high unemployment, (2) a lot of crime, or (3) a lot of corruption, as well as any combination of the three, were coded as 1.

Lastly, an autocratic measures index is created. Specifically, it adds support for military security, an iron fist government, closing institutions, an authoritarian leader, and a military coup. This variable counts the number of measures the individual supports and ranges from 0 to 5. The measure of support for harsher penalties is excluded from this index.

Independent Variables

The current study examines the influence of six key independent variables on the outcomes described above: (1) anti-welfare attitudes, (2) racist attitudes, (3) anti-LGBTQ attitudes, (4) sexist attitudes, (5) economic anxiety, and (6) fear of crime. Anti-welfare attitudes are measured with agreement to the statement, “Some people say that people who get help from government social assistance programs are lazy” (“Strongly disagree” = 1, “Strongly agree” = 7). Agreement with the statement, “Some say that, in general, people with dark skin are not good political leaders” ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 4 (“Strongly agree”) is used to measure racist attitudes. Anti-LGBTQ attitudes are measured averaging across the items, “How strongly do you approve or disapprove of (1) homosexuals being permitted to run for public office, and (2) same-sex couples having the right to marry?” (alpha = 0.71). These were each measured on a scale of 1 (“Strongly approve”) to 10 (“Strongly disapprove”).

Sexist attitudes are captured according to agreement (“Strongly disagree” = 1, “Strongly agree” = 4) with the statement, “Some say that, in general, men are better political leaders than women.” A survey item asking respondents to describe their overall economic situation as “Very good” (= 1) to “Very bad” (= 5) is used to measure economic anxiety. Finally, fear of crime was measured with an index of five dichotomous items asking about behavioral responses to fear of crime. Respondents were asked whether, out of fear of being a crime victim, in the last 12 months they (1) limited the places where they shop, (2) limited the places where they go for recreation, (3) felt the need to move to a different neighborhood, (4) organized with neighbors or their community, or (5) changed their job (alpha = 0.66).

Control Variables

Variables that were identified as potential sources of punitiveness or authoritarianism and also are related to any of the key independent variables are also included in the analyses. First, victimization was measured based on respondents answering “Yes” (= 1) to a question asking whether they or a member of their household had been a victim of robbery, burglary, assault, fraud, blackmail, extortion, violent threats, or any other type of crime in the past 12 months.

Demographic control variables include marital status (partner via marriage or common law marriage = 1, other = 0), gender (male = 1), and age in years. Respondents’ socioeconomic status is captured with a measure that reflects how many goods out of 13 possible items (i.e., television, refrigerator, telephone, vehicle, washing machine, microwave oven, indoor plumbing, indoor bathroom, computer, internet access, flat panel TV, and a sewage system connection) are in the respondent’s home (alpha = 0.82). This measure is preferable to an income measure because differences in currencies across countries can compromise the reliability of the cross-national comparisons. Additionally, respondents identified their social class on a scale from “lower class” (= 1) to upper class” (= 5). We also account for education, measured by the number of years of schooling completed (“None” = 0, “18 or more” = 18).

An ordinal measure captures respondents’ personal religiosity (“Religion is not important at all” = 1, “Religion is very important” = 4). Political ideology is measured on a scale of left (= 1) to right (= 10), along with whether the respondent would either vote for the incumbent if an election were held next week (= 1). Finally, respondent’s race is measured with five mutually exclusive dummy variables: White, Native, Black, Mestizx, and Other, with Mestizx used as the reference category.

Country-Level Variables

Egalitarian democracy from the V-Dem data captures the egalitarian principle of democracy. It assumes that inequalities (material and immaterial) preclude individuals to access to full citizenship and exercise their rights. The egalitarian democracy index combines the electoral democracy and the egalitarian component indexes, the latter comprised of indexes representing equal protections, equal access to power, and the equal distribution of resources.

Liberal democracy also comes from the V-Dem dataset. It combines the electoral democracy index with the liberal democracy component. The Liberal democracy component is constructed by combining the three different principles that should be guaranteed for the principle of liberal democracy to be achieved: equality before the law and individual liberty, judicial constrains on the executive, and legislative constrains on the executive indexes.

The human development index (HDI) comes from the United Nations Development Programme data. It combines information on health (life expectancy), knowledge (education), and standard of living (GNI per capita). Finally, victimization rate comes from the 2012 LAPOP and is constructed aggregating victimization information at the country level. Thus, it reflects the proportion of individuals that reported personal or household victimization in the country. All country-level variables are standardized.

Statistical Analyses

The proportion of missing data in each variable was relatively lowFootnote 3; therefore, we performed multiple imputation using chained equations.Footnote 4 First, we examined the individual-level sources of different forms of state violence. To do so, we first estimated multilevel logit estimations of each of our dependent variables using country-level random intercepts. Specifically, we estimated six different models predicting support for (1) harsher penalties, (2) an iron fist government, (3) military security, (4) the closure of institutions by the president, (5) an authoritarian leader, and (6) a military coup. Second, we examined the direct and indirect effects of our independent variables on our autocratic measures index through support for harsher penalties (in its original scale ranging from 1 to 4) using a multilevel SEM.

In the second stage, we explored the country-level variation in these associations by first estimating null models predicting support for harsh penalties and autocratic measures and identifying the countries in which this support is more prevalent. Second, we examined the country-level characteristics that moderate the association between support for autocratic forms of state violence and punitiveness across the six independent variables. We estimated unrestricted models with country-level slopes for each of the independent variables of interest and created scatterplots with selected country-level variables (i.e., egalitarian democracy, liberal democracy, HDI, and victimization) to visually explore their associations with each of the random slopes considered. Then, we added a cross-level interaction between each independent variable and the country-level characteristic to our full models. These models included all the individual-level independent variables and controls. To avoid multicollinearity, we included only one interaction term between each independent variable considered and the country-level variable of interest, and the random slope for the variable included in the interaction. The models predicting support for autocratic measures also included an interaction between support for harsher penalties and the country-level variable considered, along with the random slope for harsher penalties.

Results

Individual-Level Analysis

We first examine the individual-level sources of support for different forms of state violence, and results from the multilevel logit estimation are shown in Table 2. Two key independent variables—anti-welfare attitudes and fear of crime—have consistent and statistically significant associations. For anti-welfare attitudes, while a significant and positive association was found for all the dependent variables considered, the strongest association was found for support for military security (b = 0.20). Fear of crime was also consistently associated with higher likelihood of support for all the dependent variables considered, with the of these associations being support for a military coup (b = 0.27).

Each of the other independent variables’ patterns were varied. Racists attitudes were shown to be significantly correlated with support for harsher penalties, an iron fist government, and an authoritarian leader. Anti-LGBTQ attitudes were shown to significantly predict support for four out of the six outcomes: harsher penalties (b = 0.21), iron fist policies (b = 0.07), military security (b = 0.11), and a military coup (b = 0.07). Finally, sexist attitudes and economic anxiety have a positive influence on three of the six dependent variables considered: support for an iron fist government (b = 0.10), closing institutions (b = 0.12), and an authoritarian leader (b = 0.12). Economic anxieties were a significant predictor of support for harsher penalties (b = 0.07), iron fist policies (b = 0.08), and a military coup (b = 0.07). Figure 1 provides a visual representation of these relationships.

Table 3 presents the results of the multilevel SEM predicting support for harsher penalties and the autocratic violence index. Support for harsher penalties was positively associated with support for autocratic measures. All the independent variables significantly predict support for more autocratic measures, even when controlling for support for harsher penalties. Fear of crime showed the highest association with support for autocratic measures (b = 0.14), followed by anti-welfare attitudes (b = 0.08). With the exception of racist attitudes, the results show an indirect path from the independent variables to support for autocratic measures through punitiveness. While the indirect path was smaller in magnitude than the direct one, it ranged from 8% of the direct association for sexist attitudes to 33% of the direct association for anti-LGBTQ attitudes, with the proportion of the effect for anti-welfare attitudes, fear of crime, and economic anxiety falling somewhere in between (10%, 12%, and 21%, respectively).

Country-Level Analysis

Variation in Country-Level Random Intercepts Using Scatterplots

The second stage of our analyses focuses on identifying how country-level characteristics shape the associations examined. First, we examine country-level differences in support for both harsher penalties and autocratic measures. Figures 2 and 3 show the country-level random intercepts from unrestricted models plotted against country-level variables (egalitarian democracy, liberal democracy, HDI, and victimization rates). Figure 2 shows the country-level random intercepts for support for autocratic measures and suggests an inverse relationship between the level of support for harsher penalties in a country and the levels of egalitarian democracy and HD; victimization rates and liberal democracy levels seem unrelated to punitiveness. A similar though less clear pattern is observed for liberal democracy, and an even more marked pattern is seen when analyzing the HDI. Likewise, a less clear pattern is observed for victimization rates. Figure 3 shows the random intercepts for support of harsher penalties. This figure does not show a clear association between levels of democratization, HDI, or victimization rates and punitiveness. In models predicting support for autocratic measures and harsher penalties that include each of these country-level variables separately, none of them achieves statistical significance.

Variation in Country-Level Random Slopes Using Scatterplots

Second, we examine how the sources of punitiveness and support for autocratic measures vary across countries. We estimated a set of unrestricted models with only a random slope and one of the independent variables of interest at a time modeled at the country level. We show the results for the first imputation. Figure 4 shows the scatterplot of the random slopes for harsher penalties on support for autocratic measures. The figure suggests that the association between support for harsher penalties and autocratic measures is stronger in countries scoring high on the egalitarian and liberal democracy indexes (such as Uruguay and Chile).

Figure 5 shows the scatterplots of the random slopes of each of the six independent variables and support for autocratic measures at different levels of egalitarian democracy. The results for the other variables are presented in the appendix. The slopes for anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, and fear of crime are positively associated with the level of egalitarian democracy. In countries with high levels of egalitarian democracy, such as Uruguay—and, to a lesser extent, Argentina and Chile—these factors are more strongly associated with support for autocratic measures. Figure 6 shows the scatterplots of the random slopes predicting support for harsher penalties. The pattern is less clear: only the slopes for anti-LGBTQ attitudes—and to a lesser extent anti-welfare attitudes—seem to be higher in countries with higher levels of egalitarian democracy.

Formal Tests of Moderating Effects Using Cross-Level Interactions

We explore these associations formally by including cross-level interactions (as well as a random slope) in our multilevel models. Panel A of Table 4 shows a summary of the results of the models predicting support for autocratic measures. Consistent with the scatterplots, harsher penalties are more strongly associated with support for autocratic measures in countries with high levels of both egalitarian and liberal democracy. Egalitarian and liberal democracy levels also increase the salience of the two most consistent correlates of punitiveness: anti-welfare attitudes and fear of crime; the slope of the latter also moderated by the HDI (b = 0.03 p = 0.05). Further, the slope of anti-LGBTQ attitudes is also moderated by the level of egalitarian democracy and HDI, while HDI and the liberal democracy score moderate the association between sexist attitudes and support for autocratic measures. The slope of economic anxiety is only moderated by the level of liberal democracy. Notably, the victimization rate does not significantly moderate any of these associations.

Panel B of Table 4 displays select results of the cross-level interactions of each of our independent variables and the country-level variables of interest on support for harsher penalties. Only the slopes of anti-LGBTQ attitudes and economic anxiety are moderated by both egalitarian democracy and HDI. The slope of anti-welfare attitudes on egalitarian democracy is statistically significant, and the slope of anti-LGBTQ attitudes is associated with liberal democracy at the p < 0.10 level.

Examining the Conditions in Which the Associations Become Significant Using Marginal Effects

Figure 7 shows the marginal effects of the expected slope for harsher punishment on autocratic measures across different levels of the four country-level variables. The figure shows that support for harsher penalties is positively and significantly associated with support for autocratic measures across different types of countries. However, there are substantial differences in the strength of this association. For example, for countries two standard deviations below the mean of the egalitarian democracy score, the expected slope is 0.13 (p < 0.05), while for countries 2 standard deviations above the mean the predicted slope is 0.33 (p < 0.05). In contrast, the association between support for harsher penalties and support for autocratic measures is roughly similar across countries with different levels of victimization, ranging from 0.24 (p < 0.05) to 0.22 (p < 0.05) for countries two standard deviations below and above the mean, respectively.

Figure 8 shows the marginal effects of changes on the level of egalitarian democracy on the association between our independent variables and support for autocratic measures. The figure shows that the slope of anti-welfare attitudes on support for autocratic measures is non-significant in countries 2 standard deviations below the mean score of egalitarian democracy (b = 0.01, p > 0.10) but achieves statistical significance for countries one standard deviation below the mean (b = 0.04, p < 0.05), reaching its highest value 2 standard deviations above the mean (b = 0.14, p < 0.05). The association between racist and anti-LGBTQ attitudes, economic anxieties, and fear of crime and support for autocratic measures is only significant in countries at or above the mean in egalitarian democracy scores, while the association between sexist attitudes and support for autocratic measures is significant in countries with egalitarian democracy scores at and above one standard deviation below the mean.

Finally, Fig. 9 displays the marginal effects of the slopes of the independent variable of interest at different levels of egalitarian democracy. The figure shows a significant association between anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, and economic anxiety only in countries at or above the mean in egalitarian democracy scores. Sexist and racist attitudes are not significantly associated with support for harsher penalties at any level of egalitarian democracy scores. Fear of crime, on the contrary, is significantly associated with support for harsher penalties across countries, but no substantial variation in its predicted association is observed across values of egalitarian democracy.

Discussion

In this paper, we explore the role of the consolidation of the penal state in the erosion of democracy in Latin America, which drove the third wave of democratization and is arguably in a process of democratic recession (EIU, 2020; Pérez-Liñán & Polga-Hecimovich, 2017; Pérez-Liñán et al., 2019; V-Dem, 2021). We depart from more traditional analyses of the penal state that focus on the configuration of the penal field, the expansion of incarceration, and the unequal administration of justice (Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2012, 2018; Sozzo, 2016), examining the social conditions that gave public legitimacy to penal states across the Global North to understand support not only for punitive measures but for a wide range of autocratic measures in Latin America. Thus, we highlight a different mechanism through which the penal state may undermine democracy: by fostering broad support for autocratic modes of government. Overall, our findings provide support for our hypothesis; the public sensibilities that configurate the culture of control are both directly associated with support for authoritarian forms of government and also indirectly associated through increased punitiveness, which is itself associated with support for authoritarian measures. Importantly, these associations seem to be moderated by country-level characteristics, being more salient in countries with higher levels of democratization (measured through Egalitarian and Liberal Democracy Index) and social achievements (measured but the Human Development Index). Below we parse out our results and discuss their meaning and implications.

The Punitive Turn in Latin America: General Explanations of Punitive Attitudes

The literature on punitiveness has discussed the importance of anxieties and animosity towards marginalized groups in late modernity. Indeed, our results show that support for harsher punishment in Latin America seems to be driven by animosity towards marginalized groups (anti-welfare and racist attitudes) and a range of social, economic, and criminal anxieties associated with the advent of late modernity (anti-LGBTQ attitudes, economic anxiety, and fear of crime). Sexist attitudes, however, were not associated with support for harsher penalties. There is ample debate in the literature about the specific components that configure a late modern sensibility and under what circumstances they fuel punitive attitudes (Beckett, 2020; Garland, 2001; Wacquant, 2009, 2010). Our findings suggest that individuals who oppose new societal configurations are more likely to support harsh penalties. It is unclear, however, whether these views stem from a general sense of insecurity about social norms and a “moral decline” produced by late modernity or are part of a conservative worldview, a “philosophy of life,” that is correlated with support for traditional forms of authority (Beckett, 2020; Kuhn, 1993).

This region provides a valuable context to explore these issues because of the heterogeneity in the expansion of democratization. We paid particular attention to differences in the quality of democracy across countries, moving beyond a formalistic notion of democracy to account for country-level differences in adscription to two key democratic principles: egalitarianism and liberalism (Mechkova & Sigman, 2016). Egalitarian democracy is particularly related to the principles that the penal state is deemed to erode according to punishment and society scholars (Beckett & Western, 2001; Garland, 2001; Wacquant, 2010). Our findings suggest that the sensibilities that promote a “culture of control” that privileges punitiveness as a way to resolve social issues matter in some countries more than others. These associations appear particularly salient in countries with higher levels of egalitarian democracy, such as Uruguay, Chile, and Argentina. Cross-level interactions showed that this is the case particularly for anti-LGBTQ attitudes and economic anxieties. Our marginal effects analyses suggest that anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LBTQ attitudes, and economic anxieties are only relevant in countries with at least mean levels of egalitarian democracy, while fear of crime matters in every country.

Our findings suggest that the association between anti-progressive views and punitiveness—as well as support for autocratic measures—is stronger in contexts where the penetration of the new social arrangements brought by late modernity and the democratization of everyday life are higher. Importantly, punitiveness per se seems not to be idiosyncratic of more democratic societies or those with higher levels of development. Rather, our findings reveal that the processes described by Global North narratives of punitiveness—anti-progressive attitudes and animus towards marginalized populations—seem to be more applicable to describe punitiveness in societies that more closely resemble those in the Global North. Note also that victimization rates—a proxy for crime rates—seem not to moderate these associations, suggesting that crime itself is not what drives bottom-up punitive waves.

Our study thus provides keys to understanding the narratives that promote the translation of social and political anxieties into demands for order, control, and authoritarian actions from the state. Our results provide support for Garland’s idea that cultural sensibilities related to late modernity are important. We found that fear of crime and, to a lesser extent, economic anxieties are positively associated with support for punitiveness. Resentment towards marginalized populations is also associated with greater support for punitive policies as well as autocratic measures. Still, it is unclear whether these insecurities are an expression of the new anxieties characteristic of everyday life in late modern societies or are the results of other phenomena, such as the expansion of market-based neoliberal policies throughout the region.

The relationship between democratization and neoliberalism has been explored in Latin America (Weyland, 2004) and linked to the consolidation of the penal state (Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2012, 2018). However, as Sozzo (2016, 2017a) argues, even when many countries in Latin America embarked in a post-neoliberal era—where left-leaning governments enacted a variety of anti-neoliberal reforms, promoted social inclusion, expanded the welfare state, and advanced the process of democratization—incarceration rates continued to increase. Sozzo calls for more research analyzing the proximate causes (e.g., institutional arrangements, political struggles) that shape the penal field. Our analysis departed from an institutional study of the configuration of the penal state to offer a different perspective to this debate. While the social anxieties that Garland (2001) attributes to late modernity can also be associated with the expansion of neoliberalism in the region and the precarization of labor associated with it, the expansion of neoliberalism per se seems insufficient to explain the transformation of the penal field in Latin America and the political pressures from the public faced by elected officials.

Understanding the social sensibilities regarding crime and punishment and the predominant narratives that articulate a solution to those problems is crucial. Notably, in countries where transitional democracies were more consolidated and achieved higher levels of inclusion of marginalized populations and better living conditions, the ontological insecurities and social resentments seem more strongly associated to punitive attitudes. Our analyses are based on data obtained in 2012, where most of the post-neoliberal governments described by Sozzo (2016) were still in power. However, public punitiveness remained remarkably high. The level of support for harsher penalties was 88% in the region—with especially high levels in the countries described by Sozzo as post-neoliberal, including Argentina (85%), Brazil (93%), Ecuador (90%), and Uruguay (77%). As Sozzo (2017a, 2017b) suggests, absent a strong counter-narrative about the problem of crime, the pressures of “governing through crime” likely constrained the political viability of a progressive crime control agenda.

The Overarching Consequences of the Punitive Turn

Scholars have discussed how the social conditions promoting ontological insecurities and the expansion of “othering narratives” facilitate the dismantling and reconfiguration of welfare policies and the expansion of the punishment apparatus (Beckett & Western, 2001; Garland, 2001; Simon, 2007; Wacquant, 2009, 2010). This process has also been linked to the consolidation of populist authoritarian parties in the Global North, which threaten democratic institutions from within (Norris & Inglehart, 2019). Our study expands upon these findings to show that public claims emerging in this context are not limited to the legal exercise of state power within a democracy. Rather, they cascade into support for more aggressive responses that broaden the legitimacy of autocratic modes of government. Specifically, our results show considerable overlap between the sources of punitiveness and the correlates of support for a wide range of autocratic measures, lending credence to the notion that the correlates of punitiveness have overarching consequences.

Importantly, not all variables predicted every outcome. All independent variables were associated with support for an iron fist government, but only three were significantly correlated with support for the militarization of security (anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, and fear of crime) and the president’s closing of institutions under certain circumstances (anti-welfare attitudes, sexist attitudes, and fear of crime). Further, only economic anxiety and anti-LGBTQ attitudes did not predict support for an authoritarian government. Anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, economic anxiety, and fear of crime were all associated with support for a military coup, while sexist and racist attitudes were not. Two variables were consistently correlated with all variations of state power: anti-welfare attitudes and fear of crime.

Additionally, our multilevel SEM models showed that punitiveness is a predictor of support for autocratic measures. Beyond the direct association between our independent variables and autocratic measures, we found an indirect association between anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, sexist attitudes, economic anxiety, and fear of crime on support for autocratic measures that operates through increased support for harsher punishments. The only exception in this case was racist attitudes, which were directly associated with support for autocratic measures but did not operate through punitiveness. Additional analyses, available upon request, revealed that support for harsher penalties is predictive of each of the autocratic measures considered.

In all cases, both anti-welfare attitudes and fear of crime remain consistently associated with higher likelihood of support for each measure. Together, our findings suggest that the social sensibilities from late modernity undermine democracy by promoting the consolidation of a penal state that excludes citizens from full participation in democracy and further marginalizes the poor (Iturralde, 2016). Moreover, they also allow for a bottom-up erosion of democratic institutions by engendering support for autocratic modes of governance. Importantly, the mere promotion of punitiveness sets a path through which this culture of control also indirectly operates. The elements of the culture of control predict support for autocratic measures directly and indirectly by increasing support for punitive claims, which are, in turn, associated with greater support for autocratic measures. Our study underscores how the social sensibilities that drove the consolidation of the penal state in Latin America may have set limits to its democratization by promoting autocratic claims from the public. Therefore, the most salient mechanisms that explain the legitimation of autocratic measures are anti-welfare attitudes, fear of crime, and punitiveness itself.

The heterogeneity across Latin American countries allows us to identify the contexts in which the “governing through crime” pressures become more salient for promoting support for autocratic modes of government. Our cross-level interaction analyses show that the association between support for harsher penalties and autocratic modes of government is stronger in countries with higher levels of both egalitarian and liberal democracies. It is in societies that have achieved higher levels of egalitarian and liberal democracy where the specific “governing through crime” pressures translate more strongly into support for autocratic measures. Thus, though none of the country-level variables considered was significantly associated with higher country-level support for autocratic measures in our multilevel models, more democratized societies seem to be particularly vulnerable to the democracy-eroding pressures of “governing through crime.” However, our marginal effects analyses show that harsher penalties are significantly associated with support for autocratic modes of government across all levels of egalitarian democracy, suggesting that the pressures of this mode of governance foster support for autocratic measures across different contexts, though with different levels of saliency.

Finally, our cross-level interactions reveal that egalitarian democracy increases the association between anti-welfare attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, and fear of crime and support for autocratic measures. Anti-welfare attitudes, sexist attitudes, economic anxiety, and fear of crime are also more strongly associated with support for autocratic measures at higher levels of liberal democracy, while anti-LGBTQ attitudes, sexist attitudes, and fear of crime are moderated by HDI. Notably, victimization rates do not moderate any of the associations. Our marginal effect analyses also suggest that the sensibilities of the “culture of control” become relevant only in specific contexts. For example, anti-welfare attitudes do not appear significantly associated with support for autocratic measures in countries with extremely low scores of egalitarian democracies (i.e., two standard deviations below the mean), while racist attitudes, anti-LGBTQ attitudes, and economic anxieties translate into higher support for autocratic measures in countries with at least mean levels scores of egalitarian democracies. Fear of crime, on the other hand, is consistently associated with support for autocratic measures, suggesting that, though its relevance may be exacerbated by advances in democratization, it remains a mechanism of pervasive importance. The association between racist and anti-LGBTQ attitudes, economic anxieties, and fear of crime and support for autocratic measures is only statistically significant in countries at or above the mean in egalitarian democracy, while the association between sexist attitudes and support for autocratic measures is significant in countries with egalitarian democracy scores at and above one standard deviation below the mean.

Expanding the Scope of Research on Punitive Attitudes

Our study is not without limitations. First, not all of the measures available in these data fully capture the concepts we quantify. For example, our “racist attitudes” measure is comprised of one item asking individuals whether they support “dark-skinned” individuals running for office. Future studies should aim at exploring these issues using instruments specifically developed to account for the constructs elaborated in the previous scholarship. Second, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow us to establish temporal order. The relationship between support for autocratic governments and the social anxieties of late modernity is likely self-reinforcing, with support for autocratic measures also influencing the sentiments we identified as our predictors of interest. Additional research is needed to disentangle the nuanced relationship between different attitudes and how they evolve over time, particularly in relation to political debates. While our cross-country analysis provides important insight into this issue by taking advantage of the heterogeneous democratization processes occurring in the region, future research also should focus on better specifying the particularities of each country, understanding how within-county changes in institutional contexts affect these relationships.

Finally, our analyses are circumscribed to the study of differences in the sources of public opinion across Latin American countries. Thus, they do not focus on explaining the institutional dynamics through which differences in attitudes across countries differentially translate into varied outcomes such as actual levels of punishment, authoritarian actions from state officials, or even support or election of specific authoritarian leaders and parties. Scholars highlight how punitiveness is not the only key to understand differences in levels of punishment across countries—even if public punitiveness may emerge from similar social sources—and how the specific institutional configurations, actors, and incentives within each country explain how public opinion translates into policy (Garland, 2018; Tonry, 2007, 2009). Future research should focus on better disentangling how public opinion processes promoting populist punitiveness as well as populist authoritarianism differentially impact the political and institutional landscape across countries and what are the factors that facilitate the actual enactment of both a punitive and an authoritarian agenda.

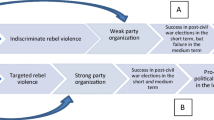

Our results suggest that the broad narratives that account for global transformations in sensibilities about crime and punishment do apply to the Latin American context and have important consequences. Figure 10 illustrates the conceptual model we build in our study and the expanded research agenda it promotes. Paying attention to the important differences that exist across Latin American countries, we also find that these processes become more salient precisely in those countries in which democracies are more consolidated and have achieved higher levels of equality and inclusion. Future research should also consider specific processes and institutions that constitute “proximate causes” of penal configurations and authoritarian turns (Garland, 2018; Pérez-Liñán et al., 2019; Sozzo, 2016; Tonry, 2007), including the role of public opinion, and identifying how certain elements may trigger support for different state responses.

The conclusions from this study are limited to Latin America, which is marked by historically unstable democracies and high levels of inequality, social exclusion, and violence—intensified by the expansion of neoliberal policies in the last decades of the twentieth century (Iturralde, 2016; Müller, 2012, 2018; Wacquant, 2010; Weyland, 2004). In fact, in the years that elapsed since these data were collected, several democratic disruptions took place in the region, such as the impeachment and removal of President Dilma Rousseff and the subsequent election of Jair Bolosnaro, a leader with a strong authoritarian rhetoric (Pérez-Liñán & Polga-Hecimovich, 2017; Pérez-Liñán et al., 2019).

Explanations of the punitive wave which emphasize the importance of the advance of late modernity and neoliberalism—and the erosion of democracy they generate—have originated in the Global North to account for changes in social sensibilities and modes of governance in Western industrialized societies. Our findings highlight how the social forces that allow for the expansion of “governing through crime” may not only consolidate a penal state but also plant the seed for public support for autocratic government. Importantly, it is not the weakest countries in the region that seem more vulnerable to these pressures but rather those with more consolidated and high achieving democracies. Future scholarship should incorporate these insights and expand the range of outcomes examined within studies of public punitiveness, particularly in a context of rising concerns about authoritarianism and the progressive erosion of democratic institutions from within (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018; Norris & Inglehart, 2019). Our study highlights how the “democracy at work” pressures may generate a bottom-up erosion of the institutions that make public claims relevant and may help consolidate progressively autocratic governments. Looking at the global South, we identify a larger set of political consequences that have been historically conceptualized as endemic problems of the region. Future research on the Global North should consider this mechanism and examine whether and how the “culture of control” sensibilities that legitimized the use of discretionary power from state actors at the expense of the marginalized may trigger a democratic recession within consolidated democracies. This endeavor seems particularly pressing given our finding that the identified elements appear to operate more strongly in those countries that resemble those from the Global North, where these mechanisms were originally identified.

Notes

The shifts in punishment discussed throughout this article have been characterized by different authors using two different but interrelated terms: the “carceral” and “penal” state. Both terms refer to a distinct set of actors and institutions that shape and enact penal policies and have been defined differently and sometimes interchangeably in the literature (Rubin & Phelps, 2017). In this article, we consistently refer to the”penal state” and understand it as encompassing a broader set of institutions and actors than those strictly carceral (jails and prisons).

Authors’ own translation from the original quote in Spanish.

Only 3 out of the 23 variables considered exceeded 10% of missing cases. Political ideology was the variable with most missing cases (18%) followed by vote for incumbent (16%) and support for closing institutions (11%). Estimations using (1) listwise deletion and (2) multiple imputation and then deletion of data originally missing on the dependent variables yield substantially the same results as those presented.

Following White, Royston, and Wood’s (2011) suggestion to generate as many imputed datasets as the maximum fraction of missing information (× 100), we imputed 30 datasets.

References

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim crow. Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. New Press.

Baker, J. O., Cañarte, D., & Day, L. E. (2018). Race, xenophobia, and punitiveness among the American Public. The Sociological Quarterly, 59, 363–383.

Beckett, K. (1997). Making crime pay: Law and order in contemporary American politics. Oxford University Press.

Beckett, K. (2020). The culture of control revisited. In C. Chouhy, J. C. Cochran, & C. L. Jonson (Eds.), Criminal justice theory: Explanations and effects (pp. 27–50). Routledge.

Beckett, K., & Sasson, T. (2003). The politics of injustice: Crime and punishment in America. SAGE.

Beckett, K., & Western, B. (2001). Governing social marginality. Punishment & Society, 3, 43–59.

Bell, M. C. (2020). Legal estrangement: A concept for these times. ASA Footnotes, 48, 7–8.

Bergman, M., Kessler, G., Delito, A. L., & Kessler, Y. G. (2008). Vulnerabilidad Al Delito y Sentimiento de Inseguridad En Buenos Aires: Determinantes y Consecuencias. Desarrollo Económico, 48, 209–234.

Bobo, L. D., & Thompson, V. (2010). Racialized mass incarceration poverty, prejudice, and punishment. In H. R. Markus & P. Moya (Eds.), Doing race: 21 essays for the 21st century (pp. 322–356). Norton.

Brown, E. K., & Socia, K. M. (2017). Twenty-first century punitiveness: Social sources of punitive american views reconsidered. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 33, 935–959.

Buckler, K., Swatt, M. L., & Salinas, P. (2009). Public views of illegal migration policy and control strategies: A test of the core hypotheses. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 317–327.

Carreras, M. (2013). The impact of criminal violence on regime legitimacy in latin America. Latin American Research Review, 48, 85–107.

Carrington, K., Hogg, R., & Sozzo, M. (2016). Southern criminology. British Journal of Criminology, 56, 1–20.

Chiricos, T., Welch, K., & Gertz, M. (2004). Racial typification of crime and support for punitive measures. Criminology, 42, 358–390.

Clear, T. R. (2007). Imprisoning communities. Oxford University Press.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Alizada, N., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Agnes Cornell, M., Fish, S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Hindle, G., Ilchenko, N., Krusell, J., Lührmann, A., Maerz, S. F., & Ziblatt, D. (2021a). V-Dem dataset v11.1. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Altman, D., Bernhard, M., Cornell, A., Fish, M. S., Gastaldi, L., Gjerløw, H., Glynn, A., Hicken, A., Lührmann, A., Maerz, S. F., Kyle, L., Mcmann, K., Mechkova, V., Paxton, P., & Sundtröm, A. (2021b). V-Dem codebook v11.1 (Issue March). Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Coppedge, M., Gerring, J., Knutsen, C. H., Lindberg, S. I., Teorell, J., Marquardt, K. L., Medzihorsky, J., Pemstein, D., Alizada, N., Gastaldi, L., Dle, G. H.-, Pernes, J., Römer, J. von, Tzelgov, E., Wang, Y., & Wilson, S. (2021c). V-Dem methodology v11.1 (Issue March). Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.

Costelloe, M. T., Chiricos, T., & Gertz, M. (2009). Punitive attitudes toward criminals: Exploring the relevance of crime salience and economic insecurity. Punishment & Society, 11, 25–49.

Cullen, F. T., Fisher, B. S., & Applegate, B. K. (2000). Public opinion about punishment and corrections. Crime and Justice, 27, 1–79.

Dammert, L., & F. Salazar. (2009). ¿Duros Con El Delito?: Populismo e Inseguridad En América Latina.

de Azevedo, R. G., & Cifali, A. C. (2017). Public security, criminal policy and sentencing in Brazil during the Lula and Dilma Governments, 2003–2014: Changes and continuities. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 6, 146–163.

Dhami, M. K. (2005). Prisoner disenfranchisement policy: A threat to democracy? Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 5, 235–247.

Dowler, K. (2003). Media consumption and public attitudes toward crime and justice: The relationship between fear of crime, punitive attitudes, and perceived police effectiveness. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 10, 109–126.

EIU. (2020). Democracy index 2019: A year of democratic setbacks and popular protest. The Economist Intelligence Unit.

Enns, P. K. (2016). Incarceration nation. Cambridge University Press.

Fernandez, K. E., & Kuenzi, M. (2009). Crime and support for democracy in Africa and Latin America. Political Studies, 58, 450–471.

Frost, N. A. (2010). Beyond public opinion polls: Punitive public sentiment & criminal justice policy. Sociology Compass, 4, 156–168.

Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. University of Chicago Press.

Garland, D. (2005). Prefacio a la Edición en Español. In La cultura del control. Crimen y orden social en la sociedad contemporánea. Gedisa

Garland, D. (2018). Theoretical advances and problems in the sociology of punishment. Punishment and Society, 20, 8–33.

Garretón, M. A. (2003). Incomplete democracy: Political democratization in Chile and Latin America. University of North Carolina Press.

Grajales, M. L., & Hernández, M. L. (2017). Chavism and criminal policy in Venezuela, 1999–2014. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 6, 164–185.

Hall, S. (1978). Policing the crisis: Mugging, the state, and law and order. Macmillan.

Hilgers, T., & MacDonald, L. (2017). Introduction: How violence varies: Subnational place, identity, and embeddedness. In T. Hilgers & L. Macdonald (Eds.), Violence in Latin America and the Caribbean: Subnational structures, institutions, and clientelistic networks (pp. 1–36). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hogan, M. J., Chiricos, T., & Gertz, M. (2005). Economic insecurity, blame, and punitive attitudes. Justice Quarterly, 22, 392–412.

Iturralde, M. (2016). Democracies without Citizenship. New Criminal Law Review: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal, 13, 309–332.

Johnson, D. (2001). Punitive attitudes on crime: Economic insecurity, racial prejudice, or both? Sociological Focus, 34, 33–54.

Kleck, G., & Jackson, D. B. (2017). Does crime cause punitiveness? Crime & Delinquency, 63, 1572–1599.

Kornhauser, R. (2015). Economic individualism and punitive attitudes: A cross-national analysis. Punishment & Society, 17, 27–53.

Kuhn, A. (1993). Attitudes towards punishment. In A. Alvazzi del Frate, U. Zvekic, & J J. M. van Dijk (Eds.), Understanding crime. Experiences of crime and crime control (pp. 271–288). UNICRI.

Kurtenbach, S. (2019). The limits of peace in Latin America. Peacebuilding, 7, 283–296.

Lacey, N. (2013). Punishment, (Neo)liberalism and social democracy punishment. In J. Simon & R. Sparks (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of punishment and society (pp. 260–268). SAGE.

Latinobarómetro. (2021). Informe 2021: Adiós a Macondo. Corporación Latinobarómetro.

Lehmann, P. S., & Pickett, J. T. (2017). Experience versus expectation: Economic insecurity, the great recession, and support for the death penalty. Justice Quarterly, 34, 873–902.

Lehmann, P. S., Chouhy, C., Singer, A. J., Stevens, J. N., & Gertz, M. (2020). Out-group animus and punitiveness in Latin America. Crime and Delinquency, 66, 1161–1189.

Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. 2018. How Democracies Die. Crown.

Lührmann, A., & Lindberg, S. I. (2019). A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization, 26, 1095–1113.

Malone, M. F. T. (2010). The verdict is in : The impact of crime on public trust in central American Justice Systems. Journal of Politics in Latin America 4:99–128.

Mechkova, V. and R. Sigman. 2016. Varieties of democracy (V-Dem). Policy Brief. V-Dem Institute.

Metcalfe, C., Pickett, J. T., & Mancini, C. (2015). Using path analysis to explain racialized support for punitive delinquency policies. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 31, 699–725.

Michener, J. (2019). Policy feedback in a Racialized polity. Policy Studies Journal, 47, 423–450.

Müller, M. M. (2012). The rise of the penal state in Latin America. Contemporary Justice Review, 15, 57–76.

Müller, M. M. (2018). Governing crime and violence in Latin America. Global Crime, 19, 171–191.

Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, Brexit, and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press.

Ousey, G. C., & Unnever, J. D. (2012). Racial–ethnic threat, out-group intolerance, and support for punishing criminals: A cross-national study. Criminology, 50, 565–603.

Paladines, J. V. (2017). The “Iron Fist” of the citizens’ revolution: The punitive turn of Ecuadorian left-wing politics. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 6, 186–204.

Pearce, J. (2010). Perverse state formation and securitized democracy in Latin America. Democratization, 17, 286–306.

Pérez-Liñán, A., & Polga-Hecimovich, J. (2017). Explaining military coups and impeachments in Latin America. Democratization, 24, 839–858.

Pérez-Liñán, A., Schmidt, N., & Vairo, D. (2019). Presidential hegemony and democratic backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016. Democratization, 26, 606–625.

Pickett, J. T. (2016). On the social foundations for crimmigration: Latino threat and support for expanded police powers. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32, 103–132.

Pickett, J. T. (2019). Public opinion and criminal justice policy: Theory and research. Annual Review of Criminology, 2, 405–428.

Pickett, J. T., & Chiricos, T. (2012). Controlling other people’s children: Racialized views of delinquency and whites’ punitive attitudes toward juvenile offenders. Criminology, 50, 673–710.

Pickett, J. T., Mears, D. P., Stewart, E. A., & Gertz, M. (2013). Security at the expense of liberty: A test of predictions deriving from the culture of control thesis. Crime & Delinquency, 59, 214–242.

Piven, F. F. (2015). “Neoliberalism and the welfare state. Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy, 31, 2–9.

Ramirez, M. D. (2013). Punitive sentiment. Criminology, 51, 329–364.

Roberts, J. V., Stalans, L. J., Indermaur, D., & Hough, M. (2002). Penal populism and public opinion: Lessons from five countries. Oxford University Press.

Rubin, A. T. (2011). Punitive penal preferences and support for welfare: Applying the ‘governance of social marginality’ thesis to the individual level. Punishment & Society, 13, 198–229.

Rubin, A. T., & Phelps, M. S. (2017). Fracturing the penal state: State actors and the role of conflict in penal change. Theoretical Criminology, 21, 422–440.

Simon, J. (2007). Governing through crime: How the war on crime transformed american democracy and created a culture of fear. Oxford University Press.