Abstract

In recent years, U.S. community colleges have seen a surge in implementing apprenticeships, particularly within their degree programs in the form of degree apprenticeships (DAs) (Browning and Nickoli, Supporting Community College Delivery of Apprenticeships. Jobs for the Future, 2017). Despite their role as champions of vocational education, the school-based nature of existing vocational programs at these institutions often lacks employer involvement. DAs engage employers as primary stakeholders, creating a robust form of work-based learning. This qualitative case study explores mentoring in DAs, a crucial component for apprentice success. Harper College, known for its DA programs in modern occupations in the greater Chicago area, serves as the research site. Findings reveal Harper’s two-tier mentoring approach: First, Harper provides coaching for apprentices, ensuring academic success and bridging school-to-work learning. Second, employers also provide mentoring in the workplace, but this experience varies greatly based on the company’s resources, size, and culture. A recurring theme for effective workplace mentoring is that it involves a collective effort, encompassing both formal and informal mentoring. Finally, Harper, as an apprenticeship sponsor, supports new employers by offering workplace mentor training—an essential service, given that most U.S. employers are relatively new to apprenticeships. This case study provides valuable insights into structuring mentoring in DAs to create an integrated learning experience within the U.S. context. However, due to the inherent limitations of a case study for generalizing findings, future research is recommended to encompass a broader range of cases, thus generating more comprehensive strategies and best practices for mentoring within DAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, apprenticeships, after a period of relative neglect, have received renewed interest in the U.S. as an effective means to prepare young people for the modern workplace. Apprenticeships became formally recognized in the U.S. with the passage of the National Apprenticeship Act in 1937 as part of efforts to overcome the Great Depression (Klor De Alva and Schneider 2018). However, they have mainly existed within construction trades and unions as secondary options for low-perform high school students, and have never fully been established as a viable career pathway (Lerman 2013). This contrasts to German-speaking countries where apprenticeships have been an integral part of the overall education system, contributing to the low youth unemployment rate and the strong economy (Hoffman 2015). The U.S. education system has rather focused on academic preparation with an emphasis on pursuing higher education, assuming that more academic achievement will improve career readiness (Hoffman 2011; Lerman 2013; Hamilton 2020).

Amidst growing concerns among educators and employers that U.S. schools are not adequately preparing young people for the demands of contemporary work (Kuchinke 2013; Hart Research Associates 2015; Helper et al. 2016; Hamilton 2020), there has been an increasing number of initiatives aimed at reestablishing apprenticeships with modern occupations and integrating them into the formal education system. Notably, there is a surge in community colleges offering registered apprenticeships, formally recognized apprenticeship programs by the U.S. Department of Labor (Browning and Nickoli 2017), within their degree programs, referred to as degree apprenticeships (DAs). Community colleges, serving as the primary vocational education and training providers in the U.S., play a significant role in enhancing the employability of students (Klor De Alva and Schneider 2018). Given their established position in U.S. vocational education, community colleges are well-suited to take the lead in institutionalizing dual apprenticeships through DAs—apprenticeships offered in collaboration with both educational institutions and employers.

One of the crucial components of DAs is the mentor-apprentice relationship (Roberts et al. 2019). The essence of apprenticeships is that young people interact with and learn from experienced workers. Scholars (Hamilton 1990; Hamilton and Hamilton 1997; Helper et al. 2016) have indicated that mentors not only assist apprentices in acquiring technical skills at the workplace, but also coach them on general workplace competencies such as punctuality, responsiveness to supervision, and communication. Additionally, mentors often provide young people with advice on personal and professional growth, and form emotional connections (RTI International n.d.). For these reasons, Helper et al. (2016) argue that the mentor-apprentice relationship is the single most important success factor of on-the-job training.

However, DAs are a relatively new phenomenon and little research has explored how mentoring in DAs is implemented at U.S. community colleges. Roberts et al. (2019) suggests that mentoring in DAs should provide a thorough induction to the company; set workplace expectations of professionalism; facilitate learning within and outside of the workplace; encourage development of professional networks; and support the achievement of the job functions and competencies required for the completion of apprenticeships. However, given that the primary purpose of a workplace is to produce goods and services, it cannot be taken for granted that employers have the capability to effectively provide workplace mentoring in partnership with higher education institutions (HEIs) (OCED 2018). Rather, employers should be supported through policy and relevant training to play the mentoring role successfully.

During the past three years, more than one hundred community colleges have joined the Expanding Community College Apprenticeships (ECCA) initiative (American Association of Community Colleges n.d.) to offer degree apprenticeships in both modern and traditional occupations. The growth of DAs is not unique to the United States. Countries without strong traditions of apprenticeship are also adopting DAs as a strategy to modernize apprenticeships and attract students and companies. For instance, the United Kingdom has witnessed rapid growth in DAs since the formulation of Degree and Higher Level Apprenticeships (D&HLAs) in 2014. In the 2019/20 academic year, 26% of newly launched apprenticeship programs were DAs, reflecting a 7% increase compared to 2018/19 (Hubble and Bolton 2019). With the increasing interest in DAs both in the U.S. and beyond, it is both meaningful and timely to examine the implementation of DA mentoring.

Purpose of the study

The purpose of this qualitative case study is to explore design and delivery of mentoring in DAs at a community college based on perceptions of primary stakeholders—community college, employers, and apprentices. By doing so, this study provides practical insights into effective mentoring for higher education institutions and employers interested in offering DAs. In a broader sense, this study also offers implications for apprenticeship research and policy, and raises awareness of the recent growth of DAs in the U.S. among international scholars.

Brief history and missions of U.S. community colleges

Before discussing DAs at community colleges, this section provides a brief history of this post-secondary sector and their mission. Community colleges are a unique part of the U.S. higher education system, which promote broad access to postsecondary education (Baker III 1994; Baime and Baum 2016). Initially established as junior colleges, their main purpose in the early 1900s was to provide the first two years of the baccalaureate degree so that four-year universities could focus on their research mission. In addition to academic programs, these colleges also offered vocational courses to serve local business and industry needs (Jacobs and Worth 2019; Vaughan 1985). The vast expansion of community colleges came from 1950 to 1975, spurred by the Truman Commission in 1947 that promoted job skills programs at community colleges for returning G.I.s. The local desire for greater postsecondary education for the broad middle class also contributed to the rapid expansion. Later, the changing social context from the 1960s through the 1980s influenced community colleges to fulfill the needs for lifelong learning and support for economic development (Baker 1994). In the 1990s, community colleges confronted new challenges of globalization and technology innovation. These forces have placed a great emphasis on work-based learning and training to increase student employability and global competitiveness (Boggs 2010).

Due to changing political and economic conditions, the mission of community colleges has evolved over time (Grubbs 2020). Currently, their core mission can be organized into three broad functions: academic transfer, remedial/development education for underrepresented populations, and vocational education (Baker 1994; Baime and Baum 2016). First, community colleges are to fulfill their most traditional role of preparing students for four-year colleges or universities by offering academic courses. Second, with their open admissions policies, community colleges provide remedial/developmental education for those who do not possess college-level skills, such as high school dropouts, immigrants with limited English proficiency, and illiterate adults. Lastly, but certainly not least, community colleges offer vocational programs, both short- and long-term, which include industry licenses and certifications to improve the job readiness of their students (Levin 2001). This role, as providers of career technical education (CTE), which is the U.S. brand for vocational education, is of particular interest in this study. The following section discusses the current development of CTE and how DAs can enhance the overall career technical education in the U.S. through strong involvement of employers in providing workforce education.

Career technical education and degree apprenticeships

Traditionally, vocational education in the U.S. has been regarded as a less ideal option for those who did not thrive at school. Perceived as a separate realm from general education, vocational students were stigmatized as those who “work with their hands” (Rosenstock 1991). Later, in 1990, the Carl D. Perkins Vocational and Applied Technology Act (Perkins II) attempted to fix this dualism by emphasizing the integration of both academic and occupational skills in vocational education (Hayward and Benson 1993). In 2006, a further effort was made to rebrand vocational education as career and technical education (CTE), which now serves as the primary vocational education training at the secondary, postsecondary, and adult education levels. The new term, CTE, was formally adopted by the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Improvement Act of 2006 (Perkins IV) to demonstrate the intent for reforming U.S. vocational education (Kuchinke 2013).

Currently, the CTE curriculum offers 79 Career Pathways across 16 Career Clusters including agriculture, architecture, business, communications, health science, hospitality, information technology, public administration, and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) (Advance CTE n.d.). Also, it has increased the rigor of the curriculum to overcome the previous perception of less demanding programs for low-performing students (Xing et al. 2020). As a result, research (Dougherty 2016; Xing et al. 2020) indicates that the transformation and rebranding of CTE has had some positive impact in reaching more students.

However, CTE is primarily delivered in a school-based setting, without significant involvement from employers in providing workplace training (Renold et al. 2018). Consequently, while taking a few CTE courses at school might help students explore some career options, it is not sufficient to fully prepare them for the world of work (Kuchinke 2013). Moreover, CTE is still stigmatized as being of less value than an academic program even among employers (Gauthier 2020).

In this regard, the recent growth of degree apprenticeships at community colleges is noteworthy. DAs combine degree programs with apprenticeships, the strongest form of workplace learning (Hamilton 2020), and involve a tripartite work-based learning partnership, with higher education institutions (HEIs), employers, and students as the main stakeholders (Basit et al. 2015). DAs enable young people to gain real-world work experience while pursuing higher education with little or no debt (Universities UK 2017). Registered apprenticeships in the U.S. require 2,000 hours of on-the-job training in addition to 144 hours of related in-class instruction (U.S. Department of Labor n.d.-a). It is the strong involvement of companies in training young people that differentiates apprenticeships from existing CTE programs. As apprenticeships are gaining renewed attention, there has been a growing interest in connecting CTE to apprenticeships to create an integrated vocational education pathway (Kreamer and Zimmermann 2017; U.S. Department of Education 2017).

Mentoring in degree apprenticeships

Successful implementation of dual apprenticeships requires several interconnected features in place. First, the workplace should be utilized as a learning environment (Fuller and Unwin 1999; Bailey et al. 2004; Darche et al. 2009; Hamilton 2020). Second, learning should be planned and delivered both at work and at school with a goal of acquiring vocational knowledge and expertise (Fuller and Unwin 1999). Third, connecting work experience to academic learning is essential for a successful apprenticeship experience (Hamilton and Hamilton 1997; Darche et al. 2009). Another crucial component of DAs is the mentor-apprentice relationship, the focus of this study. Given that workplace mentors have more interactions with apprentices than anyone else involved in apprenticeships, the importance of mentoring for successful apprenticeship experiences cannot be stressed enough.

Mentoring is broadly defined as support and guidance provided by a member of the work community to develop a mentee’s competence in acquiring knowledge, skills, and self-confidence over time (Hastings and Kane 2018). While previous research has interchangeably used various terms related to interventions occurring at workplaces, such as coaching, mentoring, and supervision (Mikkonen et al. 2017), it commonly suggests that workplace mentoring is a collective and collaborative process that involves numerous social relations (Tanggaard 2005; Filliettaz 2011; Mikkonen et al. 2017). While mentoring is typically provided by experts to novices, as suggested in situated learning theory (Lave and Wenger 1991), it is also often exchanged among fellow learners. The collective nature of workplace mentoring indicates the socio-cultural nature of vocational learning (Filliettaz 2011), where learning is regarded as an ongoing process shaped by participation in social practice (Billett 1998) and social relations play a significant role in workplace mentoring (Holland 2009).

Workplace mentoring can take different forms, depending on the extent of planning involved. It can be structured, with pre-defined objectives and implementation plans, or unstructured, involving learning that takes place through everyday work activities and interactions between experienced workers and peers (Jacobs and Park 2009). Even when unstructured Billett (2002) argues that learning from such mentoring is not incidental or ad hoc, since it is a result of the learning culture and situational factors of the workplace that contribute to opportunities for participation in learning.

In DAs, employers partner with HEIs to offer workplace mentoring that facilitates apprentices to apply what is learned in class. However, when employers are new to apprenticeships, it cannot be assumed that employers are prepared to effectively lead apprentices in workplace mentoring in collaboration with HEIs (OECD 2018). For this reason, some more experienced HEIs provide short workshops and handbooks to support employers in workplace mentoring. Some HEIs also implement their own coaching/mentoring within the school to fill any potential gaps in workplace learning, since, depending on the company’s readiness and resources, apprentices are likely to have a varying range of workplace mentoring experiences (Rowe et al. 2017).

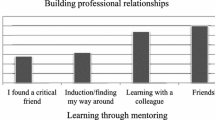

To support the learners in DAs effectively Roberts et al. (2019, p. 12) suggests mentoring should entail the following objectives. First, mentoring should provide thorough induction to the company. This includes establishing agreed ways of mentoring and identifying what areas of the organization apprentices need to understand immediately for successful onboarding. Second, workplace expectations of professionalism should be addressed by mentors. This indicates assisting apprentices in understanding the organizational culture, structure, and norms, and modeling professional behaviors expected at the organization. Third, mentoring should facilitate learning within and outside of the workplace. Mentors should regularly review apprentices’ work progress, assist them in setting goals, and facilitate reflection on the applications of knowledge and skills. Fourth, apprentices should be encouraged to develop professional networks beyond the organization. Finally, mentors should support apprentices to fulfill the job functions and competencies required for the completion of the apprenticeship.

Method

Research design

This study used a qualitative approach to explore how mentoring is designed and delivered in DAs at a U.S. community college. A qualitative study focuses on understanding how people interpret their experiences and make sense of them, rather than finding cause and effect or explaining the distribution of certain attributes in a target group (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). Since this research did not intend to test or prove a hypothesis about the design and delivery of mentoring in DAs (Creswell and Creswell 2017), a qualitative approach was the most appropriate. Also, a qualitative study is best-suited when a topic has not yet been well-researched in the literature, such as the topic of this study.

In addition, this study used a case study design. This allows the researcher to explore a case or cases—a process, program, or set of contemporaneous events—among individuals or groups to examine the complexity of social phenomena situated within a context (Stake 2005; Yin 2003). Apprenticeships are designed based on the available local businesses and resources, which affects relations among the various stakeholders. To explore in depth the complexity of how mentoring is implemented in DAs in collaboration with the stakeholders, this study focuses on the single case of a community college that offers DAs.

Case description

The selection criteria used for this study were (1) a community college with at least three to four years of experience implementing DAs in modern occupations, such as business, healthcare, and information technology and (2) whose programs were well-established to attract employers and students. I conducted an extensive online search to identify an ideal case using a combination of several keywords (e.g., community colleges, modern apprenticeships, degree apprenticeships), and reviewed exemplary stories of community colleges successfully offering DAs published by the U.S. Department of Labor (n.d.-b) and social policy research organizations, such as Jobs for the Future (n.d.-a) and Urban Institute (n.d.).

The case selected for this study was DA programs at Harper College in the Greater Chicago area in the State of Illinois. Harper received an American Apprenticeship Initiative (AAI) grant of $2.5 million in 2015 to form an apprenticeship team within their Workforce Solutions department. During the grant period (2015–2020), a team of five full-time members, in addition to several part-time marketing and sales specialists, was formed to implement DAs. During this period, the college successfully designed ten DAs in the areas of banking, marketing/sales, graphic art, supply chain management, and IT generalist. These programs with modern occupations take two years to complete. Apprentices typically spend Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at an assigned company and the other days at school focusing on coursework.

After several years of successfully implementing apprenticeships, Harper also hosted national apprenticeship conferences in 2018 and 2019 to share best practices with interested higher education institutions in the United States. As of 2021, Harper had worked with about 55 employers. Depending on their size and hiring strategies, some employers hired one or two apprentices at a time, but some hired in the double-digits to fill their entry-level opportunities each year. At Harper, companies covered college tuition and full-time salary for apprentices. This could add a financial burden to employers, but the State of Illinois provides a tax credit of $3500 per apprentice per year, which brings down the entire two-year apprenticeship tuition to approximately $5500. Overall, employers indicated a 94% satisfaction rate, and about 65% of companies have returned to hire additional apprentices.

Participant recruitment

Target participants were those who had been involved in implementing mentoring in DAs, including both apprenticeship team members at Harper and those who had served as workplace mentors at partner companies. In addition, apprenticeship graduates were targeted to capture their experience of mentoring in DAs.

Purposeful sampling was used to recruit target participants through emails, online introductions, and online search using LinkedIn, a large professional networking platform in the United States. Participation was voluntary without any incentives or compensation. Using the contact information on the Harper website (https://www.harpercollege.edu/apprenticeship), I first made a contact with the director and the manager of Harper apprenticeship programs in 2019. This led to more introductions through snowball sampling. Following the director’s recommendation, recruitment efforts were focused on DAs within the Department of Business, Entrepreneurship and Information Technology, which has the largest student enrollment among all the departments offering DAs.

The main challenge in participant recruitment was recruiting workplace mentors and graduates. Recruiting workplace mentors was done directly through email outreach by the Harper apprenticeship manager, and I did not have any control over the process. Nine workplace mentors were contacted, and only two who demonstrated interest were interviewed. Recruiting graduates also turned out to be somewhat challenging since some host company did not want their apprentices to share their experiences publicly. This created a nuanced tension, and, as a result, graduate recruitment was done solely through a LinkedIn search without any involvement from the Harper apprenticeship team. Twelve graduates were contacted on LinkedIn, and two volunteered to join the study.

Participants

In the end, a total of eight participants made up the study: two workplace mentors and two graduates, as mentioned above, and four Harper staff. These core apprenticeship team members were in the Workforce Solutions department at Harper during the grant period (2015–2020) and included (1) the director who supervised the entire DAs, (2) the manager who oversaw the operations and conducted regular workplace visits, (3) the academic coach who provided coaching for apprentices at Harper, and (4) the part-time mentor trainer who provided training for workplace mentors. Table 1 presents a list of the eight participates and their roles.

Data collection

Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, online observation, and document analysis. First, interview questions were designed based on the literature review to explore the design and delivery of mentoring in DAs. These questions included:

-

For Harper: Describe how mentoring in your DAs is designed and delivered. What types of support do mentors provide? What types of support does Harper provide for workplace mentors?

-

For workplace mentors: Describe how workplace mentoring is designed and delivered at your company. What types of support do you provide for apprentices through mentoring? How is it structured?

-

For graduates: Describe mentoring that you received during your apprenticeship. How was it structured? How did it help with your apprenticeship experience?

All the interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom. Recorded files were saved on my personal hard drive that is password-protected. Each interview lasted for 60–90 min on average. Recorded interview files were transcribed and shared with the participants to ensure accuracy.

In addition, I was invited to observe online mentor training conducted by Mentor Trainer. Since apprenticeships are still new to most employers in the U.S., Harper provided two half-day training sessions for new workplace mentors. Sessions were usually scheduled two weeks apart to allow some time for participants to apply what they learned and reflect between the sessions. The training was previously offered in-person, but due to the restrictions with COVID at the time of the study, it was handled virtually through Zoom. I attended both sessions in February 2021. The participants were fourteen female mentors from a healthcare provider that had just launched a nursing apprenticeship program with Harper. At the beginning of the first session, the mentor trainer introduced me and briefly explained the purpose of my participation. Once the sessions started, I turned off my microphone and camera not to interfere with their activities and conversations as an “observer as participant” (Merriam and Tisdell 2016, p. 144). Detailed field notes were recorded using word-processing software during the observation to retain the training topics, activities, questions from the mentors, responses and reactions, and my observations on the facilitation style and techniques.

Finally, the Train-the-Trainer (TTT) manual, a 28-page online document created by Harper College (2015) for the mentor training, was analyzed as a supplemental resource to verify findings from the online mentor training observation.

Data analysis

Data analysis in qualitative research is the process of meaning-making to answer research questions (Flick 2018). As suggested by Bogdan and Biklen (2011), data analysis occurred simultaneously with data collection to draw tentative themes that could then be followed up in subsequent interviews. I first transcribed and organized data in MAXQDA2020, qualitative data analysis software. Second, while reading through each transcript, I color-coded data with notes, reflections, and questions to observe themes. This was repeated until themes were identified and organized since data analysis in qualitative research is an iterative process (Merriam and Tisdell 2016). Finally, codes were grouped into three themes and nine subthemes to answer the research question.

To ensure validity and reliability, data was first collected from various stakeholders and through several resources for data triangulation. Next, the findings were further verified through email exchanges with the apprenticeship program manager at Harper for member checking (Creswell and Creswell 2017). Finally, the findings are presented here with thick and rich descriptions (Merriam and Tisdell 2016).

Findings

This study reveals that mentoring within Harper DAs adopts a two-tier approach: academic coaching provided by Harper and workplace mentoring from each employer. Academic coaching at Harper focuses on holding apprentices accountable for their academic progress, while workplace mentoring emphasizes the acquisition of both technical and soft skills essential for workplace success. However, the actual scope of their coaching/mentoring extends beyond these primary goals, bridging learning between school and work to create an integrated learning experience and jointly manage apprentices in DAs. Given that existing literature tends to focus more on mentoring taking place in the workplace (Giacumo et al. 2020), this two-tier approach constitutes a unique aspect of mentoring in DAs at Harper.

With this approach as the overarching theme, this study’ findings are organized into three themes and nine sub-themes. The first two themes explore the structure of DA mentoring through academic coaching at Harper and workplace mentoring on the job. The third theme investigates how Harper supports companies in implementing workplace mentoring by training their mentors, with an emphasis on their role in connecting learning at school and work.

Academic coaching at Harper—academic success and beyond

Support academic success for apprentices

The primary goal of academic coaching in Harper DAs is to ensure successful academic progress for apprentices since failed courses can lead to disqualification from the apprenticeship program. Staff 3, who served as the academic coach, met with apprentices on a regular basis, both as a group and individually, to check on their academic progress, encourage them to stay on track, and sometimes simply facilitate a group study. While academic coaching often occurs at community colleges to support learners, what sets it apart in the context is DAs is that Harper actively engages employers in this process, enabling an additional layer of accountability for the academic success of apprentices, as outlined in their agreement according to Staff 3:

I always tracked for all their grades. I had direct connection to all the instructors, so I knew if they were not going to class, if their behavior was not appropriate in class. And I immediately had to address these things with the company as well, because that was an agreement between this college and the companies, for them to have an idea what’s going on with their students.

Her interactions with employers would also bring up behavioral and/or performance issues of apprentices at work, which led to the extended scope of academic coaching at Harper as discussed in the next section.

Support apprentices to develop professionalism at work

While the primary goal of academic coaching in DAs at Harper is to ensure the academic success of apprentices, frequent interactions with apprentices also enabled Staff 3 to assist them in developing professional behaviors and navigating issues at work. For example, Staff 3 would arrange group coaching sessions to address workplace issues as they emerged. Topics were as simple as calling the boss when they became ill, being punctual at work, or commonly addressed soft skills topics such as SMART goal settings, time management, and leadership development. Staff 3 emphasized the importance of flexibility in adjusting coaching topics to address workplace issues in a timely manner:

I would advise the apprentice you need to talk to your manager, and this is how I would approach that situation. Coaching topics really depended on what was going on. If there were a lot of people really struggling with certain things, then, okay, next week, we’re going to get together and discuss that. I think that flexibility is key.

This example indicates that coaching at Harper extends beyond ensuring academic success to connect school and work since successes at these locations are interconnected in DAs. This also demonstrates that coaching provided by Harper enabled the joint management of apprentices with employers, which is a crucial function of mentoring within DAs, as discussed in the following section.

Facilitate joint management of apprentices between Harper and employers

On-going interaction between Harper’s academic coach and employers facilitated joint management of apprentices as they discussed concerns over academic progress and workplace issues and sought to address them collectively. This was especially helpful since most employers in the program were still learning about how to best support apprentices to achieve their goal of cultivating a long-term talent, as demonstrated in Staff 3’s story:

I’d make sure that employers were doing what they’re supposed to be doing, because companies in the U.S. aren’t used to apprenticeships. So a lot of what I had to do was to work with them to figure out how to support apprentices, (sometimes) suggesting some ideas and thoughts. For example, we had an apprentice who was good with academics. But he had more insecurities and fear of messing up. I advised the company that you need to encourage him every single step of the way, telling him that he is doing a great job. As soon as the company changed their whole philosophy on how to coach him, they saw a total or complete change in him. After the summer, the student came back to me and said, I’ve really grown up, like I’m taking responsibility… And now he’s training all these other apprentices at his company.

The three sub-themes in academic coaching discussed so far indicate that the scope of coaching at Harper goes beyond academic success to bridge the educational institution and the workplace. This theme is also salient in workplace mentoring, which is discussed next.

Mentoring at the workplace—workplace success and beyond

Support workplace success for apprentices

The importance of workplace mentoring cannot be stressed enough since, as Mentor Trainer stated, “A mentor is the one person who has the most contact with the apprentices, so if the apprentice is going to be successful, it is going to be the direct result of the mentor.” Staff 1 also affirmed the importance of mentoring by simply stating, “Everyone knows that the better the mentors, the better the apprentices.”

To ensure workplace success for apprentices, workplace mentors established regular meetings with apprentices to check for appropriateness of work, coach for work skills as well as handling workplace issues and dynamics, and even offer support for issues outside of work, as Workplace Mentor 2 commented:

I go through their log. I make sure that their work is appropriate, and that it’s not clerical in nature, that it is driven by the position that they’re going to eventually move into once the apprenticeship is complete. I (also) want to be sure that they’re not struggling with any of the concepts, so if we need to spend more time on instruction we will. We (also) try to be as open as possible with all our employees to help them through the struggles they are having. I think they felt a lot more emotional support, especially in 2020.

Connect learning at school and at work

Another significant aspect of workplace mentoring in the context of DAs is “connecting what apprentices are learning at school and at work,” as mentioned by Staff 2. Harper emphasizes workplace mentors serving as the linkage between the academic and business world by helping apprentices apply in-class learning at the workplace. However, due to the structured and sequenced nature of academic courses, which may not always align with the specific job skills required in the workplace, linking school learning with on-the-job experience on a day-to-day may seem somewhat ambiguous, as Workplace Mentor 1 expressed:

As an employer, we need more structure and understanding how to better apply the skills they’re learning day to day to help them get where they need to go.

In this regard, Workplace Mentor 2 recognizes that the alignment of learning at school and work in DAs appears to be defined at a high level, in terms of general knowledge and competencies required for the occupation, rather than at a granular level:

Harper teaches more of general education… (while) the training that we do is a lot more specific to the job. We are not really able to arrange their work around their learning at Harper because their courses are more general, but they’re right in line as far as what they’re doing and what they’re learning.

This comment provides an important insight into what it entails to serve as the link between school and work as a workplace mentor: (1) being cognizant of what apprentices are learning at school, (2) making a connection at work when applicable, and (3) providing extra accountability for their academic progress when needed. This role as the link between school and work is emphasized in Harper’s mentor training, which is discussed further in the final theme section.

Structure of workplace mentoring varies greatly depending on companies

Exploring how employers structure workplace mentoring in this learn-and-earn degree pathway is certainly one of the key interests of this study. Interviews revealed that employers commonly implemented formal, regular touchpoints with apprentices, utilizing predefined agendas to monitor their progress. This practice was consistently observed in workplace mentoring in Dual Apprenticeships (DAs). In addition to these scheduled meetings, interviewees reported experiencing varying degrees of structured versus unstructured mentoring, depending on the company’s level of preparedness and available resources. For example, Graduate 1 described her mentoring experience at a large insurance company as highly structured with multiple mentors assigned whenever she rotated through different departments. Since her company hired a group of apprentices to train altogether, she undergone structured on-the-job training with her cohort of apprentices. In contrast, Graduate 2 was the very first and only apprentice at the local bank where he served. He expressed that he was “their guinea pig in the sense that they were all learning on the fly.” However, he added that in some ways, “everyone mentored” the only apprentice that they had. These comments seem to demonstrate that U.S. employers, still new to apprenticeships, are in the process of establishing best practices for themselves.

Who serves as a mentor also varies among companies. While manager-level employees appear to be commonly assigned as a mentor, this was not always the case in the study. Workplace Mentor 2, the vice president of her company, initially served as a mentor herself, until the company learned how apprenticeship works and assigned one of the supervisors to take up the role. In Workplace Mentor 1’s company, the HR department plays an official role as a mentor. This has been working well, since it allows apprentices to have “consistent mentorship throughout their program” even when they move between different departments and managers.

Regardless of how mentoring is structured, a common theme emerged that gives a sense of what creates successful workplace mentoring experiences, which is discussed below.

What creates effective workplace mentoring experience

One notable observation I made regarding successful workplace mentoring is that it requires a concerted effort through both formal and informal mentoring within the organization. While a registered apprenticeship in the U.S. mandates an assigned mentor to work with an apprentice, in reality, it takes more than one mentor to help apprentices to grow their skills and become acclimated to the company. Workplace mentoring is a team effort. An assigned mentor is formally responsible for checking apprentices’ work progress to ensure their accomplishment of the required competencies. At the same time, other colleagues may support apprentices through informal mentoring to help them onboard with the job, understand the organizational culture and norms, model professional behaviors, and teach specific job skills (Roberts et al. 2019).

Interviews clearly demonstrated the combination of formal and informal mentoring that contributes to the positive mentoring experience. This was also intentionally arranged by the assigned mentor. For example, Workplace Mentor 2 purposefully included a layer of colleagues, such as supervisors and co-workers, to invest in apprentices. This was one of the key strategies to get apprentices acclimated to the company’s culture and help them develop a sense of belonging:

I’m very involved (as an assigned mentor). And then the actual supervisor is talking to the apprentice constantly. So she’s much more involved in the day-to-day stuff. We also have their co-workers totally involved in this and we do it for a reason. Their co-workers know what their work is like, and they can help them to be a lot more efficient on the job. So I think that’s worked very well as far as getting them acclimated to our culture.

Informal mentoring could even involve an experienced apprentice mentoring a novice apprentice, as was the case with Graduate 2. When he started to feel stuck in a “monotonous tone with the position” during his 2nd year of apprenticeship, his manager encouraged him to mentor a new apprentice who had just graduated from high school. This peer mentoring relationship provided Graduate 2 with renewed motivation for his apprenticeship and turned out to be “one of the highlights of the apprenticeship program.”

Facilitating informal mentoring between an apprentice and existing employees has another advantage. It increases organizational commitment to the apprenticeship. For example, after an initial “disjointed” mentoring experience, Workplace Mentor 1 strategically involved other managers in the planning and hiring process to get them more invested and create a more integrated process:

If you’re involved in hiring the apprentice, you are going to be involved in managing and helping the apprentice to develop more like long term relationships. Previously, it was much more like our executive team hired the apprentices, and then handed them off. We’re taking away the handoff. This is going to be a very integrated program.

Mentor training provided by Harper

So far, I have explored a two-tier arrangement of mentoring in the Harper DA programs. Now, this section dives into how U.S. employers, who may not be familiar with the idea of degree apprenticeships, prepare themselves for workplace mentoring, and what role, if any, Harper plays in supporting them. Rowe et al. (2017) suggests that some experienced HEIs develop their own short workshops and handbooks to support employers in DAs. This is the case with Harper. Harper provides training to equip new workplace mentors to be successful in their roles. The last theme of the study explores the primary focus of mentor training at Harper.

Mentor Trainer stated that mentors are “teachers, role models, networkers, counselors and life-long learners.” They should be “people-oriented, open-minded, flexible, empathetic and collaborative” to facilitate the experience of apprentices. Harper College (2015) presents mentors’ responsibilities as: supervise and manage the apprentice’s OJT at the workplace; monitor their academic progress; motivate the apprentice by teaching them about the work, developing their skills, providing them with feedback and recognizing their achievements; and help them be aware of co-worker expectations, the company culture, and the organization’s policies and procedures.

These roles encompass both traditional workplace mentoring goals and unique objectives for DAs, such as monitoring the apprentice’s academic progress. According to the Mentor Trainer, the training is “not radically different from regular training for a new group of supervisors.” The agenda covers commonly addressed leadership and supervisory skills, such as communication, learning and coaching styles, delegation, and building trust. The main distinction lies in the emphasis on how to successfully support apprentices at work, especially by stressing the two goals described below.

Raise awareness of apprenticeships

First and foremost, the training should raise awareness of apprenticeships at the company since most participants join simply because they were told to do so by their supervisor, without any prior understanding of apprenticeships:

Their supervisor and manager came in, and said, we are gonna start apprenticeships, and I want you to become a mentor. So there is an eye-opening experience when I get to work with some mentors who didn’t really have any idea what this is all about…If there is no other reason to conduct this class, it is about the awareness of what apprenticeship is about.

This awareness includes that apprentices are less experienced than typical new hires, thus requiring an “extra level of attention,” especially at the beginning. For that, Mentor Trainer encouraged mentors to establish “how much time you should spend with your apprentice and what you should be doing.”

Help mentors serve as the linkage between the academic and business world

The second theme emphasized in the mentor training was to challenge mentors to serve as the linkage between the academic and business worlds. As the one who oversees apprentices at the workplace, a mentor needs to be cognizant of what apprentices are learning at school and be intentional about connecting it to their work, as described earlier. What is striking is that Harper takes this role one step further. Mentors are not just expected to understand and make connections to what apprentices are learning at school, but also to provide a certain level of accountability for their academic performance. This attribute of mentoring is unique for apprenticeships, and therefore needs to be reiterated throughout the training, as expressed by Mentor Trainer:

We have many case studies, “you received a call from the apprenticeship office. There is an issue in academic progress. What are you gonna do with it?” The first reaction that comes up is “why do I care? They are doing a good job in my place. It’s up to them to do a good job in the classroom.” That creates a case for us to say, you do have to care. That’s part of the unique attribute of the mentor. I always try to instill that accountability in my training.

However, Mentor Trainer added that this level of accountability is not necessarily “embraceable by some of the schools.” He is now providing mentor training for dozens of community colleges, but some colleges are concerned about emphasizing this level of accountability in the mentor training since “maybe they are not aware of that, or they don’t have the manpower to make that happen.” A mentor’s accountability for apprentices’ academic progress could certainly facilitate joint management of apprentices. However, the comments from Mentor Trainer appear to indicate that the level of expected alignment between school and work may look different among apprenticeship providers, and each needs to determine what level of alignment to pursue and evaluate their practice.

So far, this study explored the two-tier mentoring approach in DAs at Harper that enables joint management of apprentices and how Harper supports workplace mentors through training. Figure 1 below captures the key findings of the study.

Discussion

This qualitative case study provides an in-depth account of what mentoring in DAs entails at one U.S. community college. Based on the findings, I offer several suggestions for successful mentoring in DAs.

First, to ensure successful mentoring in DAs, HEIs should be prepared to provide extra support for employer partners, particularly in countries without a strong apprenticeship tradition. The study highlights the crucial role played by Harper in supporting employers to offer workplace mentoring. Harper conducts two half-day training sessions for new workplace mentors, educating them on the vision and role of apprenticeship mentoring to set them up for success. Through ongoing interactions with partner companies, Harper reinforces the mentor’s role not only as a supervisor for on-the-job training but also as a guide to the company culture to help apprentices acclimate to the company. These responsibilities generally align with the five domains of mentoring in DAs suggested by Roberts et al. (2019). HEIs interested in offering DAs should assess the support needed for employer partners based on their preparedness and available resources.

Second, HEIs and employers should establish a mentoring structure to collectively oversee apprentices and develop communication plans. Harper achieves it through a two-tier approach, combining academic coaching at the college and workplace mentoring on the job. This collaboration involves both parties determining the desired level of alignment between the two training locations. For instance, based on their agreement, Harper involves employers in ensuring academic accountability for apprentices struggling with their grades. The level of alignment can vary across different DA programs, but it is essential for HEIs and companies to reach a mutual agreement on how to manage apprentices collaboratively through mentoring to ensure their success in DAs.

Third, employers need to be strategic about including a wider range of individuals, such as supervisors, entry-level employees, or even other apprentices, in mentoring apprentices both formally and informally. This study verifies that successful delivery of workplace mentoring requires a concerted effort. This finding is consistent with previous research (Tanggaard 2005; Filliettaz 2011; Mikkonen et al. 2017) that acknowledges the mentor’s role as a shared responsibility due to the socio-cultural nature of vocational learning (Filliettaz 2011). For effective workplace mentoring in DAs, companies should establish regular formal meetings with apprentices to check their progress toward predefined competencies and provide support for work-related issues. Simultaneously, companies should strategically expand their use of informal mentoring, as it not only helps apprentices acclimate to the company but also enhances organizational commitment to apprenticeships.

Finally, at the policy level, more resources should be allocated to disseminate best practices in mentoring that create integrated learning experiences within dual apprenticeships. One of the advantages of countries with a strong tradition of apprenticeship is that most skilled workers have been an apprentice themselves, therefore understanding how to guide apprentices at work (Hamilton 2020) and ensure the acquisition of competencies aligned with work-based learning curricula for their respective occupations. This is not the case in the United States. However, with the recent growth and interest in registered apprenticeships, the government has funded a variety of resources, including online courses, webinars, handbooks, and video tutorials, to assist employers in mentoring apprentices. These resources cover diverse topics, encompassing the role of mentoring, diversity and equity in apprenticeship mentoring, as well as strategies for retaining apprentices through effective on-the-job learning (WorkforceGPS 2023). While this represents a positive step toward establishing apprenticeships in the U.S., there remains a need for guidance on how schools and companies can collaborate to jointly manage apprentices through mentoring. For instance, this study indicates that U.S. employers may lack clarity on the day-to-day aspects of connecting learning in DAs in collaboration with schools. Addressing this lack of clarity, the findings highlight the mentor’s role in being aware of learning at school and making connections at work when applicable, all while recognizing that learning alignment generally occurs at a high level, rather than at a granular level. Disseminating this insight can enhance role clarity among key stakeholders managing learning in DAs.

Conclusion, limitation, and recommendations

As an exploratory study of a new learn-and-earn degree pathway, this research contributes to the limited body of existing studies on degree apprenticeships in the context of a U.S. community college. It delves into the dynamics of the tripartite relationship in work-based learning, with a specific emphasis on mentoring as a crucial element in fostering a successful learning experience. The findings of this study provide a foundational framework outlining the key features of mentoring in DAs, elucidating how these elements synergize to optimize learning in dual apprenticeships. These insights can be invaluable for practitioners and researchers seeking to enhance the quality of these educational initiatives.

While this case study has provided an in-depth description of a journey of one U.S. community college to design and deliver mentoring in degree apprenticeships, a case study is limited in generalizing the findings. Also, it only included a small number of workplace mentors due to the recruitment challenge. While the mentors who participated provided rich insights into the research question, which was also supplemented by interviews with graduates, I recommend that future research include more cases to have a greater in-depth analysis of challenges and strategies for mentoring in DAs. Such research could formulate evidence-based principles and recommendations for effective workplace mentoring as a guide for interested HEIs and employers. It could also enrich the experiences of student apprentices as more HEIs in the U.S. and beyond offer DAs to bridge the gap between school and work.

Data availability

The author confirms that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Advance CTE (n.d.) Career clusters. https://cte.careertech.org/sites/default/files/CareerClustersPathways_0.pdf

American Association of Community Colleges (n.d.) Expanding community college apprenticeships. https://www.aacc.nche.edu/programs/workforce-economic-development/expanding-community-college-apprenticeships/

Bailey TR, Hughes KL, Moore DT (2004) Working knowledge: work-based learning and education reform. Psychology Press

Baime D, Baum S (2016) Community colleges: multiple missions, diverse student bodies, and a range of policy solutions. Urban Institute. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED570475.pdf

Baker III GA (1994) A handbook on the community college in America: its history, mission, and management. Greenwood Press

Basit TN, Eardley A, Borup R, Shah H, Slack K, Hughes A (2015) Higher education institutions and work-based learning in the UK: employer engagement within a tripartite relationship. High Educ 70(6):1003–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9877-7

Billett S (1998) Understanding workplace learning: cognitive and sociocultural perspectives. In: Boud D (ed) Current issues and new agendas in workplace learning. NCVER, pp 43–59

Billett S (2002) Workplace pedagogic practices: co–participation and learning. British J Edu Stud 50(4):457–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8527.t01-2-00214

Bogdan R, Biklen SK (2011) Qualitative research for education: an introduction to theories and methods. Prentice Hall

Boggs GR (2010) Growing roles for science education in community colleges. Science 329(5996):1151–1152. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1194214

Browning B, Nickoli R (2017) Supporting community college delivery of apprenticeships. Jobs for the Future. https://www.jff.org/resources/supporting-community-college-delivery-apprenticeships/

Busemeyer MR, Trampusch C (2012) The comparative political economy of collective skill formation. In: Busemeyer MR, Trampusch C (eds) The political economy of collective skills formation. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199599431.003.0001

Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2017) Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage

Darche S, Nayar N, Bracco KR (2009). Work-based learning in California: opportunities and models for expansion. James Irvine Foundation. https://www.wested.org/online_pubs/workbasedlearning.pdf

Dougherty SM (2016) Career and technical education in high school: does it improve student outcomes? Thomas B. Fordham Institute. https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/career-and-technical-education-high-school-does-it-improve-student-outcomes

Flick U (2018) An introduction to qualitative research. Sage

Filliettaz L (2011) Collective guidance at work: a resource for apprentices? J Vocat Educ Train 63(3):485–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2011.580359

Fuller A, Unwin L (1999) A sense of belonging: the relationship between community and apprenticeship. In: Ainley P, Rainbird H (eds) Apprenticeship: towards a new paradigm of learning. Kogan Page Limited, pp 150–162. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315042091

Gauthier T (2020) A renewed examination of the stigma associated with community college career and technical education. Community Coll J Res Pract 44(10–12):870–884. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2020.1758835

Jacobs J, Worth J (2019). The evolving mission of workforce development in the community college. Community college research center working paper no. 107. https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-w5pw-eg92

Grubbs SJ (2020) The American community college: history, policies and issues. J Educ Adm Hist 52(2):193–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2019.1681385

Giacumo LA, Chen J, Seguinot‐Cruz A (2020) Evidence on the use of mentoring programs and practices to support workplace learning: a systematic multiple‐studies review. Perform Improv Q 33(3):259–303. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21324

Hamilton SF (1990) Apprenticeship for adulthood. Free Press

Hamilton SF, Hamilton MA (1997) Learning well at work: choices for quality. School to Work Opportunities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED411390.pdf

Hamilton SF (2020) Career pathways for all youth: lessons from the school-to-work Movement. Harvard Education Press

Harper College (2015) Trainer the trainer. https://www.harpercollege.edu/apprenticeship/pdf/TTT-Manual-1.2019.pdf

Hart Research Associates (2015) Falling short? College learning and career success. Association of American Colleges and Universities. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/files/LEAP/2015employerstudentsurvey.pdf

Hastings LJ, Kane C (2018) Distinguishing mentoring, coaching, and advising for leadership development. New Dir Stud Leadersh 158:9–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.20284

Hayward GC, Benson CS (1993) Vocational-technical education: major reforms and debates 1917-present. U.S. Department of Education Office of vocational and adult education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED369959.pdf

Helper S, Noonan R, Nicholson JR, Langdon D (2016) The benefits and costs of apprenticeships: a business perspective. U.S. Department of Commerce. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED572260.pdf

Hoffman N (2011) Schooling in the workplace: how six of the world’s best vocational education systems prepare young people for jobs and life. Harvard Education Press

Hoffman N (2015) High school in Switzerland blends work with learning. Phi Delta Kappan 97(3):29–33

Holland (2009) Workplace mentoring: a literature review. Work and Education Research & Development Services

Hubble S, Bolton P (2019) Degree apprenticeships. House of Commons Library. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8741/CBP-8741.pdf

Jacobs RL, Park Y (2009) A proposed conceptual framework of workplace learning: implications for theory development and research in human resource development. Hum Resour Dev Rev 8(2):133–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309334269

Jobs for the Future (n.d.-a) Center for apprenticeships & work-based learning. https://www.jff.org/what-we-do/impact-stories/center-for-apprenticeship-and-work-based-learning/

Jobs for the Future (n.d.-b) Apprenticeship training courses. https://www.jff.org/what-we-do/impact-stories/center-for-apprenticeship-and-work-based-learning/apprenticeship-training-courses/

Klor De Alva J, Schneider M (2018) Apprenticeships and community colleges: do they have a future together? American Enterprise Institution. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED585878.pdf

Kreamer K, Zimmermann A (2017) Opportunities for connecting secondary career and technical education (CTE) students and apprenticeship programs. U.S. Department of Education. https://cte.careertech.org/sites/default/files/files/resources/Opportunities_Connecting_Secondary_CTE_Apprenticeships.pdf

Kuchinke PK (2013) Education for work: a review essay of historical, cross-cultural, and disciplinary perspectives on vocational education. Educ Theory 63(2):203–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12018

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press

Lerman RI (2013) Expanding apprenticeship in the United States: barriers and opportunities. In: Fuller A, Unwin L (eds) Contemporary apprenticeship: international perspectives on an evolving model of learning. Routledge, pp 105–24

Levin J (2001) Globalizing the community college: strategies for change in the twenty-first century. Springer

Merriam SB, Tisdell EJ (2016) Qualitative research: a guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass

Meyer T (2009) Can “Vocationalisation” of education go too far? The case of Switzerland. Eur J Vocat Train 46(1):28–40. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ864788

Mikkonen S, Pylväs L, Rintala H, Nokelainen P, Postareff L (2017) Guiding workplace learning in vocational education and training: a literature review. Empir Res Vocat Educ Train 9(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-017-0053-4

OECD (2018) Seven questions about apprenticeships: answers from international experience. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264306486-en

Renold U, Caves K, Burgi J, Egg M, Kemper J, Rageth L (2018) Comparing international vocational education and training programs: the KOF education-employment linkage index. National Center on Education and the Economy, Washington, DC. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED589125.pdf

Roberts A, Storm M, Flynn S (2019) Workplace mentoring of degree apprentices: developing principles for practice. High Educ Ski Work-Based Learn 9(2):211–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-10-2018-0108

Rosenstock L (1991) The walls come down: the overdue reunification of vocational and academic education. The Phi Delta Kappan 72(6):434–436

Rowe L, Moss D, Moore N, Perrin D (2017) The challenges of managing degree apprentices in the workplace: a manager’s perspective. J Work-Appl Manag 9(2):185–199. https://doi.org/10.1108/JWAM-07-2017-0021

RTI International (n.d.) Work-based learning toolkit. https://cte.ed.gov/wbltoolkit/index.html

Stake RE (2005) Qualitative case studies. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds) The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage, pp 443–466

Tanggaard L (2005) Collaborative teaching and learning in the workplace. J Vocat Educ Train 57(1):109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820500200278

Universities UK (2017) Degree apprenticeships: realising opportunities https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2017/degree-apprenticeships-realising-opportunities.pdf

Urban Institute (2021) Mentoring matters: the role of mentoring in registered apprenticeship programs for youth. https://www.urban.org/events/mentoring-matters-role-mentoring-registered-apprenticeship-programs-youth

Urban Institute (n.d.) Apprenticeships. https://www.urban.org/tags/apprenticeships

U.S. Department of Education (2017) A planning guide for aligning career and technical education (CTE) and apprenticeship programs. https://s3.amazonaws.com/PCRN/reports/Planning_Guide_for_Aligning_CTE_and_Apprenticeship_Programs.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor (n.d.-a) Understanding apprenticeship basics. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/odep/categories/youth/apprenticeship/odep1.pdf

U.S. Department of Labor (n.d.-b) The roles that community colleges play in apprenticeship. https://www.apprenticeship.gov/educators/community-colleges

Vaughan GB (1985) The community college in America: a short history. Revised. American Association of Community and Junior Colleges. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED255267.pdf

WorkforceGPS (2023) Registered apprenticeship mentoring resources. https://apprenticeship.workforcegps.org/resources/2023/02/15/19/35/Registered-Apprenticeship-Mentoring-Resources

Xing X, Garza T, Huerta M (2020) Factors influencing high school students’ career and technical education enrollment patterns. Career Tech Educ Res 44(3):53–70. https://doi.org/10.5328/cter44.3.53

Yin RK (2003) Case study research: design and methods. Sage

Acknowledgements

This study was based on research conducted for the author’s doctoral dissertation. I would like to acknowledge the pivotal role of my dissertation committee members: Dr. Allison Witt, Dr. Stephan Hamilton, Dr. Ron Jacobs, and Dr. Peter Kuchinke. Their unwavering support, guidance, and expertise were foundational to this work.

Funding

The author received no funding for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

As the sole author of this paper, I confirm sole responsibility for all aspects of the study including study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of results, and manuscript preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

The author obtained approvals from the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign on July 21, 2020, where I belonged to at the time of writing, and Harper College, the research site for the study on December 17, 2020. This ensured that this study was in compliance with the protocols for conducting research with human subjects.

Informed consent

In the process of data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Voeller, J. Exploring design and delivery of mentoring in degree apprenticeships at a U.S. community college: primary stakeholders’ perspectives. SN Soc Sci 4, 44 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-024-00843-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-024-00843-7