Abstract

Salvadora persica occurs widely in the dry and semi-arid regions of the Indian subcontinent, the Middle East, and parts of Africa, where it is commonly used as a ‘toothbrush’. The present paper attempts to chronicle the history of S. persica in present-day Tamil Nadu. Sangam literature (300 BCE–300 CE) in Tamil is widely acknowledged for identifying floral and faunal elements of parts of Southern India, particularly modern Tamil Nadu and Kerala. The description of floral elements in Sangam literature, when definitively linked to the present-day scientifically determined plant identities, enables us to estimate and evaluate their present distribution. In addition, this paper collates the references to the plant ukãy from both Sangam and the later-period Tamil literature and traces the history and use of this plant in the Tamil region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Salvadora persica, the toothbrush tree (Farag et al., 2021; Sher et al., 2010), belongs to the Salvadoraceae plant family. It is a large, extensively branching evergreen shrub or small tree with soft, whitish-yellow bark and drooping branches (Khatak et al., 2010), widely distributed in North Africa and Asia from the Middle East to India and Sri Lanka. S. persica is peelu in Urdu (Platts, 1884), miswak, meswak in Arabic (Halawany, 2012; Hattab, 1997), and known by various other names elsewhere (Aumeeruddy et al., 2018). Textual sources in TamilFootnote 1 identify S. persica as ukā, ukãy, kaḷar-ukãy, kaḷarvā (Krishnamoorthy, 2011; Sreedharan, 2017; University of Madras, 1982) as do oral sources in different parts of Tamil Nadu.Footnote 2 The names given to S. persica in other Dravidian languages are: in Malayalam, uvā, ukãy or ukā-maram; in Kannada, goni; in Telugu, gunnangi and Tulu, kirgonji (Aumeeruddy et al., 2018). Though no other Dravidian names could be traced in the literature or current usage, Mukhopadhyay (2021) proposes, from a linguistic perspective, that the Dravidian root for tooth—pal—could be the root for the words that denote elephant and also S. persica in the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). This linguistic perspective is seen in the historical and cultural context of the current distribution of S. persica in the Indian subcontinent and the names by which different people know it.

2 Sangam literature and epigraphy sources

The Sangam literature (300 BCE–300 CE) and inscriptions between 300 BCE and 600 CE are important sources that help reconstruct various facets of Tamil history (Srinivasan, 2016). The available Sangam period poetry includes 2381 poems of varying lengths (some of 4 lines, such as poems of Kuṟuntokai, to the longest with 782 lines, Maturai Kāñci) written by 473 poets during varied periods from the third century BCE to the third century CE (Mahadevan, 2003). These poems have been anthologized and grouped into the Eight Anthologies (Eṭṭuttokai) and the Ten Songs (Pattuppāṭṭu). Based on their contents, these anthologies are further distinguished into akam (interior) and puṟam (exterior). The akam poetry deals with love and love-related human emotions, whereas the puṟam deals with the glory of princes, warriors, wars, the aftermath of wars, society, and morality. In the akam segment, landscape elements are glorified, linking nature and human emotions (Takahashi, 1991; Thaninayagam, 1966). For example, a widely known poem of Kuṟuntokai uses the rainwater flowing on red soil changing to red as a metaphor for the union of the lovers’ minds. In addition to natural elements, such as flora, fauna, seasons, and rain, society’s material culture, such as handicrafts, vehicles, and other human products, is also linked to human emotions in akam poems.

The inscriptions record different kings and other patrons and their contributions to social causes, such as building shelters, beds, temples, and water storage in various locations. The inscriptions on hero stones document the cause of the heroic death of a warrior or an animal protecting a village. The names of places mentioned in the inscriptions can often be correlated with names in Sangam literature. For example, Pūlāṅkuṟicci (10.2748 N; 78.5068 E) inscriptions, dated to around the fifth century CE (Subbarayalu & Varier, 1991), mention administrative divisions such as Miḻalai and Muttūṟu which correspond to the place names mentioned in one of the Sangam anthologies (Puṟanānūṟu, 18, 24). Similarly, epigraphists and historians show that the Chera kings mentioned in the Sangam anthology Patiṟṟuppattu with the Pukaḷūr (11.0769 N; 77.9974 E) inscriptions. Historians generally use this method to correspond Sangam era place names and genealogies with those in later inscriptions to locate them in present-day maps and/or geography. The present paper attempts to understand the environmental and cultural history of S. persica through such literary and epigraphic sources.

3 Salvadora persica

Salvadora persica is a slow-growing tree capable of adapting to soil conditions that range from excessively dry to highly saline. It can grow as either a large shrub or a small tree, up to 12 m high and 4.7 m girth. The main trunk is mostly erect but occasionally could be trailing. When trailing, it branches profusely, with a sprawling crown consisting of crooked, straggling and/or drooping branches. The bark of this tree is rough, greyish brown on the main trunk, and pale elsewhere. The fruit is yellow and ripens in May‒June. Mature fruits are smooth, fleshy, globose, pink-scarlet drupes up to 10 mm in diameter, with persistent calynx and single-seeded. Seeds turn pink to purple-red and are partly transparent when ripe (Kumar et al., 2012). The fruit pulp is pungent and mildly hot-spicy, as in Brassica juncea (Brassicaceae) or Piper nigrum (Piperaceae) (Kumari et al., 2017). This fruit is used in cooking for its peppery taste in the Middle-Eastern countries (Royle, 1846). This tree and seed are indicated in the Bible (New Testament) as the ‘mustard of the scripture’ (Royle, 1846) and the toothbrush tree of Prophet Muhammad (Aumeeruddy et al., 2018).

Salvadora persica is drought tolerant, which has enabled its expansive distribution in the arid parts of Africa, the Middle East, the Arabian Peninsula, and parts of the Indian subcontinent.Footnote 3 The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species in 2018 is listed as a species of ‘least concern’.Footnote 4 In India it is distributed widely in the dry and semi-arid regions of Gujarat, Rajasthan; to some extent in the semi-arid segments of Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, and Delhi; and to a lesser extent in Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu (Gunasekaran & Paramasivam, 2012; Sreedharan, 2017; Tripathi, 2016).

4 Distribution of S. persica in Tamil Nadu

Salvadora persica is not widely distributed in Tamil Nadu. Although, it is found in Ramanathapuram (9.36 N, 78.84 E) and most coastal districts of Tamil Nadu, its distribution here is not as large scale as in the Arabian Peninsula, parts of Africa, and the Middle East (Sher et al., 2010). The tree occurs sporadically, along the Eastern coastal stretch of Tamil Nadu, especially in the sacred groves recorded in the districts of Pudukkottai, Perambalur, Trichy, Villuppuram, Cuddalore, Chengalpattu, Kanchipuram, Nagappattinam, Thanjavur, Thiruvarur, Mayiladuthurai, Thoothukudi, Ramanathapuram and Thiruvallur and in the bioregion of Puducherry (Gunasekaran & Paramasivam, 2012; Gamble, 1935; Gill et al., 1998; Sreedharan, 2017) (Fig. 1). The soils are primarily coastal alluvium and coastal black soil (Britto, 2019). Flora volumes of southern India (e.g., Gamble, 1935; Udayakumar & Parthasarathy, 2010) list this taxon and ascribe diverse habitats to it: from coastal to tropical dry evergreen forests (TDEF) to slightly elevated landscapes (plateaus of Pudukkottai (c. 100 m amsl), Dharmapuri (c. 500 m amsl).

We, the authors of this article, found four trees in an urban forest patch protected by the Forests and Wildlife Department of the Government of Puducherry. The Tamil Nadu Forest Department report Heritage trees of Tamil Nadu (2017) indicates that in the Thiruchirapalli district, 215 trees are protected by Annai-Kamatchi Amman temple authority within the temple complex (10.77 N; 78.69 E). According to the report, the age of S. persica is estimated to be more than 200 years, but many trees of this species live even longer. For example, the ukãy tree seen in Apparsamy madam (a monastery) in Thiruvamur (11.77 N; 79.48 E) near Panrutti (Fig. 3) is considered by local people to be at least 200 years older. The term kaḷar-ukãy, hanging on the signboard, perfectly matches its saline and dry habitat. The prefix kaḷar, according to the University of Madras (1982, p. 812), means either a saline landscape or an alkaline landscape, which indicates the habitat of this tree. An analysis of ethnomedicinal uses of temple trees (Gunasekaran & Paramasivam, 2012) also listed S. persica as kaḷar-ukãy; however, it does not locate the temple where this tree grows.

5 Salvadora persica in Sangam literature

In the Sangam literature corpus, as mentioned earlier, landscape elements are glorified, linking nature and human emotions. Some poems in Naṟṟiṇai and Kuṟuntokai use the tree ukãy and its features in this way. Further, Panchavarnam (2020), in Caṅka-ilakkiya tāvaraṅkaḷ (Plants cited in the Sangam literature), records this tree from various literary sources beginning from the Sangam period to Bhakti period (700 CE–900 CE). The name itself is still in Tamil and is validated by botanical works, too (Krishnamoorthy, 2011; Sreedharan, 2017).

The external morphological characteristics of the tree, such as its bark, berries, parched trunk, and distribution in drylands and wastelands, leads us to conclude that ukãy referred to in Sangam literature is S. persica. The lovers’ suffering because of their separation is compared with a dry land flora in the following verses (the occurrences pertinent to S. persica in the poems are underlined):

Miḷaku peytaṉaiya cuvaiya puṉkāy

Ulaṟutalai ukāayc citarcitart tuṇṭa

Pulampukoḷ neṭuñciṉai yēṟini ṉaintutaṉ

Poṟikiḷar eruttam veṟipaṭa maṟukip

Puṉpuṟā uyavum ventuka ḷiyavu

(Naṟṟiṇai 66 (Iyer, 1956))

My lovely daughter left to be with her lover,

on a hot, dusty path, where a pigeon chases

away bees and eats small, ukãy berries that

taste like pepper, feels confused and afraid,

sits on a tall tree branch and shakes its bright,

spotted neck in pain, regretting what it did.

(Trans. by Vaidehi Herbert (2012))

Puṟavup puṟattaṉṉa puṉkā lukāayk

Kāciṉai yaṉṉa naḷikaṉi

(Kuṟuntokai 274)

Here, the trunk of the ukãy tree is soft.

as the back of a dove, and its beads of fruit.

(Trans. by A.K. Ramanujan, 2014)

Pullarai ukāay variniḻal vatiyum

Iṉṉā aruñcuram

(Kuṟuntokai 363)

go into the painful, harsh wasteland

where a noble, fine wild marai stag

with a flower strand on his horns,

takes shelter in the dappled shade

of an ukãy tree with parched trunk

(Trans. by Vaidehi Herbert, 2012)

Kuyiṟkaṇ ṇaṉṉa kurūukkāy muṟṟi

Maṇikkā caṉṉa māṉiṟa iruṅkaṉi

Ukāay meṉciṉai utirvaṉa kaḻiyum

Vēṉil veñcuram

(Akanāṉūṟu 293)

In the summer season, the unripe fruits of the ukãy tree,

looking like a kuyil’s eyes, have matured and the large ripe fruits,

with their lovely ruby-like colours

(Trans. by George Hart, 2015)

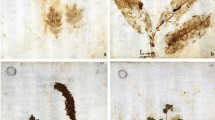

The Akanāṉūṟu (Nattar et al., 1944) mentioned above, describes ukãy as having coral-like berries which are similar to the eyes of a cuckoo and mature into dark-colored fruits that look like coins (Fig. 1). The fruits of Cordia obliqua (Boraginaceae) and Murraya koenigii (Rutaceae), often compared to cuckoo’s eyes, are relatively bigger than S. persica. The first of these, commonly known in Tamil as nariviḻi, eyes of the Jackal (Krishnamoorthy, 2011) is known to thrive only in freshwater and non-saline soils, whereas M. koenigii survives in fertile and saline soil, unlike S. persica, which requires salinity (Britto, 2019). M. koenigii is also referred in Sangam literature as kañcakam (Raghavaiyangar, 308). The characterizations of ukãy described in Sangam literature cited above and their distribution in semi-arid land fit with the present-day botanical descriptions of S. persica.

The semi-arid regions, including dry, barren, and degraded lands, are called pālai in Sangam literature. Pālai is a region that flourished once, but later, due to the absence of rain and other natural events, may turn dry and become pālai. Salinity-affected regions are also considered as pālai (Srinivasan, 2016). In Sangam literature ukãy is a tree of pālai region. Hence ukãy, based on literary evidence, can survive in adverse edaphic and other environmental conditions.

The Sangam poets use the characteristics of the dry pālai landscape to portray the depth of the separated lovers’ grief. The female persona is the most affected and anguished; the poets use similes of pālai flora and fauna to depict this anguish.

In his edition of Kuṟuntokai, Saminathaiyar (1937, p. 35) describes the characteristics of ukãy:

Ukãy. An arid zone tree is usually denoted with ‘y’ at the end when spelt with Roman letters of the alphabets and, sometimes, without it—ukā. The stem of this tree is ash coloured, and hence compared with pigeon’s back. It is evident through the occurrences puṉkāl-ukãy, pullarai-ukãy that this tree is dull coloured. Since the fruits are spherical and yellowFootnote 5 they are usually compared to gold coins. The leaves are less dense hence the shade they provide is scattered.

Fruits of Ukāy tree at Marakkanam, a high-saline coastal region (Rani & Kalaiselvam, 2018)

After the literary evidence from Sangam literature,Footnote 6Peruṅkatai, an extensive text (a kāppiyam, epic) written by a Jain (seventh century CE), mentions ukãy in pālai region (Saminathaiyar, 1935). The Jain Muni Neminatar’s grammatical treatise Nēminātam (twelfth century CE) supplies ukãy as an example of the complexity of ‘y’ ending words with its compound form ‘ukãy-p-pazham’ (1945, p. 26)—the fruit of ukãy.

Apart from the available literary evidence, inscriptional records enable us to locate the occurrences of this tree in historical contexts. A Tiruvālaṅkāṭu copper plate (attributed to Rajendra Chola I, eleventh century C.E.) mentions ukãy nine times as a boundary in a bequeathed donation (Sastri, 1987, no. 205). Tiruvālaṅkāṭu (13.1311 N, 79.7759 E), on the Chennai–Arakkonam road, is a semi-arid township, and the citation here is consistent with the current distribution of S. persica in Tamil Nadu.Footnote 7

A widely known Tamil adage for healthy teeth is ālum vēlum pallukku uṟuti (young stems of Ficus benghalensis and Acacia nilotica are healthy for the teeth). Ukãy has been used to brush teeth in northern India and the Middle East. But the Tamil adage does not include ukãy.Footnote 8 What is the likely reason for excluding S. persica from normal use in Tamil Nadu? The occurrence of S. persica is restricted to coastal regions, in contrast to the widespread presence of Ficus benghalensis (Moraceae) and Acacia nilotica in Tamil Nadu, which could be one reason for the popularity of these two trees. Interestingly, a list of chewing sticks in a recently published paper on Salvadora includes A. indica stems and S. persica as a widely used material in the Indian subcontinent (Wu et al., 2001, p. 280).

The Tamil Siddha medical tradition acknowledges using ukãy in treating various illnesses. Five head words for ukãy are found in the Siddha dictionary: ukā, ukā-p-paṭṭai, ukãya-vākai, ukãy, uvāy-p-paṭṭai (Anandan, 2008, p. 157). According to Anandan (2008), the tree bark is used as a balm for pain relief and inflammation and as a general wound healer (ibid. p. 157, 223). Interestingly, no Siddha medical treatments have identified S. persica for tooth-related issues.

6 Indus Valley Civilization (IVC): Pīlu tree

The language spoken by the people of the Indus Valley (2500 BCE to 1700 BCE) is the subject of an unresolved debate. Using linguistic and DNA analyses has made this issue more popular in recent years, especially because of the availability of sophisticated computational tools and libraries (Mohan, 2021; Mukhopadhyay, 2021). Mukhopadhyay (2021), in particular, traces the language spoken by the people of the Indus Valley through linguistic analysis, especially by selecting the names commonly used to refer to the floral and faunal elements, arguing that the Dravidian root for tooth—pal—could be the root for the words that denote elephant and also S. persica. The names of S. persica (ukãy or kaḷar-ukãy) in Tamil do not relate to tooth-related roots. However, Mukhopadhyay surmises that pīlu—which denotes S. persica in IVC—could be a proto-Dravidian root. She concludes that the Indus people might have spoken a proto-Dravidian language based on her analysis, linking a proto-Dravidian root to the Indus floral and faunal elements. However, the names used continuously in Tamil Nadu for S. persica from historical times are ukãyFootnote 9 and kaḷar-ukãy (Fig. 3).Footnote 10 In other Dravidian languages, as mentioned earlier, the names do not relate to pīlu, pal, or any tooth-related name.

7 Conclusion

Although linguistics is a powerful tool for understanding the origins of words, literature, history, and culture are essential for understanding how people use words in speaking and writing (Guy, 1990). In the case of S. persica, though a proto-Dravidian origin of its name (pīlu) is proposed, this name or its variant is not found in current popular usage or in ancient or modern Tamil literature, where this tree is known as ukãy. The name pīlu, though, has been transmitted in Sanskrit and Arabic (Meulenbeld, 2008; Mukhopadhyay, 2021), and the plant itself continues to be valued in tooth care in those regions, unlike in Tamil Nadu, where it is recognized in ancient Siddha medicine for other medicinal uses unrelated to tooth care. Thus, though qualitative and indirect, literature and historical markers like inscriptions can be a powerful complement to linguistics; other fields, such as paleo-ecology, could also help in better understanding of questions such as how long the history of S. persica goes back in peninsular India.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Ukāy seems to be recorded in some research papers as either kalawa or kakkol (Gautam, 2013, p. 309; Khatak et al., 2010, p. 209) probably because kaḷar-ukāy or kaḷarvā in spoken language could have been heard and recorded as kalawa (dropping ‘r’) given the diglossia in Tamil that can lead to non-native speakers recording what they hear as it is.

The local people in Ramanathapuram, Panrutti, Pudukkottai, Thiruchy areas call S. persica as ukāy even today.

http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:779348-1, accessed on October 23, 2021.

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/138472280/146211537, accessed on September 24, 2023.

Fruits are not yellow but brownish red (Fig. 2).

One unidentified poet of the Sangam period uses the epithet ukãy-k-kuṭi-k-kiḻār (Kuṟuntokai 63), which includes ukãy (S. persica) as a prefix. Ukãy-k-kuṭi (kuṭi means a settlement or a small village in Sangam) should have been named after this tree, although presently we are unable to locate this village. Kiḻār in classical Tamil refer to a person who belongs to a particular region.

Anantanarayanan Raman, has shared (pers comm.) his experience of seeing flourishing trees of S. persica on the Ennore shore, Thiruvallur district more than 50 years ago. This gives a record of S. persica’s distribution in Tamil Nadu.

It does not include neem (Azadirachta indica) (vēmpu) either, which is, however, used by and known to the people in many parts of Tamil Nadu.

K.V. Krishnamoorthy in Tamiḻarum tāvaramum refers to this plant as ukāy in Tamil.

In Trichy and Panrutti temples this tree has been mentioned as kaḷar-ukāy in a signage.

References

Anandan Maru, A. (2008). Citta maruttuva akarāti (Vol. 2). cittamaruttuva veḷiyīttu pirivu.

Aumeeruddy, M. Z., Zengin, G., & Mahomoodally, M. F. (2018). A review of the traditional and modern uses of Salvadora persica L. (Miswak): Toothbrush tree of Prophet Muhammad. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 213, 409–444.

Britto, S. J. (2019). The flora of central and north Tamil Nadu: Fabaceae–Loranthaceae (APG - IV), Part 2. In The flora of central and north Tamil Nadu. Rapinat Herbarium, St. Joseph’s College.

Farag, M., Abdel-Mageed, W. M., El-Gamal, A. A., & Basudan, O. A. (2021). Salvadora persica L.: Toothbrush tree with health benefits and industrial applications—an updated evidence-based review. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 29, 751–763.

Gamble, J. S. (1935). Flora of Presidency of India (Vol. I). Adlard & Son Limited.

Gautam, G. K. (2013). A review on Indian medicinal plant ‘Salvadora persica’. International Journal of Universal Pharmacy and Biosciences, 2(1), 308–316.

Gill, A. S., Bisaria, A. K., & Shukla, S. K. (1998). Potential of agroforestry as source of medicinal plants: Glimpses in plant research. In J. N. Govil (Ed.), Current concept of multi discipline approach to the medicinal plants. (Vol. II). Today and Tomorrow’s Printers and Publishers.

Gunasekaran, M., & Paramasivam, B. (2012). Ethnomedicinal uses of sthalavrikshas (temple trees) in Tamil Nadu, southern India. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 10, 253–268.

Guy, G. R. (1990). The sociolinguistic types of language change. Diachronica, 7(1), 47–67.

Halawany, H. S. (2012). A review on miswak (Salvadora persica) and its effect on various aspects. The Saudi Dental Journal, 24(2), 63–69.

Hart, G. L. (2015). The four hundred songs of love. An anthology of poems from classical Tamil. The Akanāṉūṟu. French Institute of Pondicherry.

Hattab, F. N. (1997). Meswak: The natural toothbrush. Journal of Clinical Dentistry, 8(5), 125–129.

Herbert, V. (2012). Retrived June 13, 2021, from https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/

Iyer, P. N. (1956). eṭṭuttokaiyil oṉṟākiya naṟṟiṇai nāṉūṟu mūlamum uraiyum. Tirunelvēli Caiva Cittānta Nūṟpatippuk Kaḻakam, Reprint.

Khatak, M., Khatak, S., Siddqui, A. A., Vasudeva, N., Aggarwal, A., & Aggarwal, P. (2010). Salvadora persica. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 4(8), 209–214.

Krishnamoorthy, K. V. (2011). Tamiḻarum tāvaramum (Mūṉṟām patippu). Pāratitāsan Palkalaikkaḻakam.

Kumar, S., Rani, C., & Mangal, M. (2012). A critical review on Salvadora persica: An important medicinal plant of arid zone. International Journal of Phytomedicine, 4(3), 292–303.

Kumari, A., Parida, A. K., Rangani, J., & Panda, A. (2017). Antioxidant activities, metabolic profiling, proximate analysis, mineral nutrient composition of Salvadora persica fruit: Unravel a potential functional food and a natural source of pharmaceuticals. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 61–62.

Mahadevan, I. (2003). Early Tamil epigraphy: From the earliest times to the sixth century AD. Cre-A & Harvard University Press.

Meulenbeld, G. J. (2008). A quest for poison trees in Indian literature, along with notes on some plants and animals of the Kauṭilya Arthasāstra. Vienna Journal of South Asian Studies, 51, 5–75.

Mohan, Peggy. (2021). Wanderers, kings, merchants: The story of India through its languages. Penguin Random House.

Mukhopadhyay, B. A. (2021). Ancestral Dravidian languages in Indus Civilization: Ultra conserved Dravidian tooth-word reveals deep linguistic ancestry and supports genetics. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00868-w

Mutaliyar, K. R. G. (1945). kuṇavīrapaṇṭitar iyaṟṟiya nēminātam uraiyuṭaṉ. Tirunelvēli Caivacittānta Nūṟpatippuk Kaḻakam.

Nattar, N. M. Venkatasamy, R. Vēṅkaṭācalam Piḷḷai (comm.). (1944). (comm.). eṭṭuttokaiyuḷ oṉṟāṉa akanāṉūṟu: maṇimiṭai pavaḷam. pākaṉēri ta.vai. iḷaiñar tamiḻccaṅka veḷiyītu. Jupiter Press.

Panchavarnam, I. (2020). Caṅka Ilakkiyat Tāvaraṅkaḷ. Paṇṇuruṭṭi Tāvarat Takaval Maiyam.

Platts, J. T. (1884). A dictionary of Urdu, classical Hindi, and English. W. H. Allen & Co.

Raghavaiyangar, R. (1958). Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai ārāycciyum uraiyum. Annamalai Palkalaikkaḻakam.

Ramanujan, A. K. (2014). The interior landscape: Classical Tamil love poems. NYRB Poets.

Rani, M. H., & Soundra, M. K. (2018). Diversity of halophilicmyco flora habitat in saltpans of Tuticorin and Marakkanam along southeast coast of India. International Journal of Microbiology and Mycology, 7(1), 1–17.

Royle, J. F. (1846). Art. VI.—On the identification of the mustard tree of scripture. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 8, 113–137. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00142765

Saminathaiyar, U. V. (1935). Peruṅkatai (2nd ed.). Kēcari Accukkūṭam.

Saminathaiyar, U. V. (1937). Kuṟuntokai. Kēcari Accukkūṭam.

Sastri, H. K. (1987). South Indian inscriptions, 3 (III & IV), miscellaneous inscriptions in Tamil. Archaeological Survey of India. Reprint.

Sher, H., Al-Yemeni, M., Masrahi, Y. S., & Shah, A. H. (2010). Ethnomedicinal and ethnoecological evaluation of Salvadora persica L.: A threatened medicinal plant in Arabian Peninsula. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research, 4(12), 1209–1215.

Sreedharan, C. K. (2017). Heritage trees of Tamil Nadu. A conservation project report from the Tamil Nadu Forest Department and the TVS Group.

Srinivasan, T. M. (2016). Agricultural practices as gleaned from the Tamil literature of the Sangam Age. Indian Journal of History of Science, 51(2), 167–189.

Subbarayalu, Y., & Varier, M. R. R. (1991). Pūlāṅkuricci Kalveṭṭukkaḷ. Avanam Vol. 1. pp. 57–69.

Takahashi, T. (1991). Tamil love poetry and poetics. E. J. Brill.

Thaninayagam, X. S. (1966). Landscape and poetry: A study of nature in classical Tamil poetry. Asia Publishing House.

Tripathi, M. (2016). Salvadora persica L. (Miswak): An endangered multipurpose tree of India. Indian Journal of Plant Sciences, 5(3), 24–29.

Udayakumar, M., & Parthasarathy, N. (2010). Angiosperms, tropical dry evergreen forests of southern Coromandel coast. India. Check List, 6(3), 368–381.

University of Madras. (1982). Tamil lexicon. University of Madras.

Wu, C. D., Darout, I. A., & Skaug, N. (2001). Chewing sticks: Timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. Journal of Periodontal Research, 36(5), 275–284.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Drs. S. Prasad, K. Anupama, and N. Balachandran of the French Institute of Pondicherry for their insightful suggestions and for helping improve this paper. We are particularly grateful to Dr. N. Balachandran, who helped us find S. persica trees in Pondicherry’s urban forest. We are also thankful to Professor Elaine Craddock, Southwestern University, Texas, who has helped improve the language of this paper. The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewer for his valuable comments, which helped revise the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Prakash, M.V., Anbarashan, M. The Ukãy, Salvadora persica (Salvadoraceae): Historical and literary evidence from stone inscriptions, copper plates, and literature. Indian J Hist. Sci. 59, 159–164 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43539-024-00123-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43539-024-00123-6