Abstract

This paper explains how the stagnation and crisis in Argentina (2009–2020) reshaped the standard of living of the working class and how their effects are reflected through inequality indexes. Many studies have used quintile stratification for inequality analysis. Following the traditions of Marxian/structural theoretical frameworks, we analyse inequality by defining the different factions within the working class, estimating the Socio Occupational Condition (CSO) from Census Data. This strategy allows us building different strata within the working classes from information on regular surveys. We work with the data from the Permanent Survey of Households (EPH) of Argentina. We use bootstrapping techniques to strengthen our estimations of mean income, too, in order to improve our analysis of the difference between classes and variance’s income estimator. We analyse the evolution of inequality with several generalized entropy indexes. These indexes allow us to describe the composition of inequality between the different classes and within each class. We complement the analysis with macroeconomic estimates of income distribution to include estimates for income appropriation from other social classes. We study how macroeconomic developments and policies during the recent crisis have affected inequality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

After the 2008 crisis, Argentina entered into stagnation and macroeconomic instability (Féliz, 2018; Piva, 2018). While other Latin American countries were severely hit by the crisis, Argentina’s disequilibrium created the perfect setting for the transitional crisis of the neo-developmentalist development strategy (Féliz, 2016b, 2019). This had profound social and political implications as it transformed—in different waves and stages—the social and distributive structure of the country, as has been shown in others (Castrosin & Venturi Grosso, 2016; Jaccoud et al., 2015).

Most of these analyses centre on the usual macroeconomic variables of Keynesian origin or in the traditional inequality framework that comes from human-capital theories. These studies tend to grasp social structure as organized according to the distribution of income. Such distribution is thought of as the main factor of the structuration of society. The empirical expression of such studies is generally a quintile analysis of income inequality. Income stratification is very much used. It is usually understood as an adequate approximation to the social position of the household, representing their social class. Then, we can talk about the poor, the middle classes, or the rich, with no other qualifications.

This strategy is flawed on several levels, on the one hand, to the extent that these divisions are merely conventional but not theoretical (Martínez, 1999; Wright, 1979). On the other hand, they do not help interpret the causal mechanisms of differences based on the characteristic that serves as the decision criterion. There is a strong circularity between income and social strata. Thus, for example, income strata do not explain educational attainment or the incidence of unemployment, since—on the contrary—these variables help explain the income level of a person or family. Besides, a household’s income level in itself is not an accurate indicator of its vulnerability to changing economic conditions.

The different forms of participation in the labour market or (more generally) in the economy may result in essential differences regarding their ability to absorb shocks in the economic environment. There is another tradition of inequality studies coming from the Marxian/structural theoretical frameworks (Gordon et al., 1994; Marini, 2015; Shaikh, 2016). They provide a more consistent understanding of how capitalist societies are organised and how wealth is produced, reproduced, distributed and consumed. They provide us with a class analysis of structural inequality.

The characteristics of the occupational insertion of the members of the households express the social division of labour and affect how social changes impact them (Sautu et al., 2020). Wage workers, for example, will not be equally conditioned as those who own means of production. People in management positions, high qualification and responsibility will face fewer risks than workers at the bottom of the job ladder. The ownership of means of production, the characteristics of the job position and the magnitude of the available machinery are fundamental elements to explain the evolution of living conditions. In this sense, income level is not the most crucial element in analysing social structure but how those incomes are obtained is. Thus, criteria for social stratification should seriously consider the occupational insertion of people to understand the dynamics of living conditions.

In Argentina, this framework has been recently used to explore the possibilities of understanding the process of class inequality (Sautu et al., 2020). Torrado has been a pioneer in proposing an empirical strategy (Torrado, 1994). Her analytical framework approximates the class structure from Census data for Argentina through the analysis of socio occupational condition (CSO). In principle, this strategy allows building different strata within the working classes from information on employment on regular surveys. Féliz and others have used this technique to work with the data from the Permanent Survey of Households (EPH) of Argentina (Féliz et al., 2012; Féliz & Millón, 2021), while Sautu and others have been using data from their proprietor survey on the Greater Area of Buenos Aires (AMBA).

In this article, we propose to use this framework to provide a novel empirical approximation to the dynamics of inequality in Argentina during the transitional crisis. The following section explains our approach to the class structure based on Torrado’s seminal ideas. We show some general results and (in Appendix 1) explain the possibilities and limits of our estimations. After that, we provide a political economy analysis of the evolution of inequality through the crisis. We finish presenting our conclusions and discussing future questions for this strategy.

2 Thinking on inequality from a class perspective

Income stratification is widely used and often taken as a proxy for the social position of households, in effect acting as if it represents the social class to which they belong. However, this interpretation is not really adequate and tends to generate complex problems to solve. For example, one can find that the income stratum to which a person’s household belongs has a strong impact on the probability of being unemployed. This could mean that a higher income (a higher social stratum) affects a person’s chances of finding work if he or she looks for work, or alternatively reduces the need to look for whatever work (similar to reservation wage). However, this interpretation does not take into account the fact that there is a strong circularity between unemployment (particularly of the head of household) and the level of household income. An alternative explanation could be that it is precisely the higher probability of finding employment (for unidentified reasons) that leads to higher income, and therefore to the person belonging to a better-off household on the income scale.

This problem is repeated in the case of other indicators that are strongly associated with income. For example, the educational attainment of working-age individuals is strongly positively associated with their belonging to an income stratum. Again, it is difficult to isolate the real effects of education on income levels. Neoclassical economic theory points out that there would be a positive relationship between the level of human capital (proxied by the level of formal education) and income levels, because the former would increase the productivity of labour, increasing the worker’s income (if the remuneration of the labour force is based on its marginal productivity, as assumed). Other theoretical perspectives (Bowles et al, 2000, Thurrow, 1975) point out that formal education has no important effects on workers’ productivity or on their wages, but that it acts as a filter that capitalists use to select their personnel. So, education only gives people access to better jobs (better paid, but also with better working conditions), simply because employers perceive that workers with more education have lower costs of education and training for any given task (costs that are financed by the company). In short, there might not be a direct causal relationship between education and income level.

What this is really pointing out is that income, unemployment and other variables are expressions of the same phenomenon and are therefore not independent. Moreover, as the actual inequality in opportunities faced by individuals cannot be directly deduced from the magnitude of inequality in income distribution, this stratification criterion is severely limited for the analysis of social inequality. People’s income is not enough to define what one can or cannot do, what one can or cannot achieve, since this will also depend on a variety of physical and social characteristics that affect our lives (Sen, 1997). These problems arise not only from the fact that income is only a means to our true ends, but also (1) from the existence of other equally important means to any particular end and (2) from the strong interpersonal variations in the relationship between means and our various ends (Sen, 1997). The construction of distributional inequality indicators based on income tends to ignore this circumstance. For example, Atkinson (1970) measures the magnitude of inequality based on the assumption that people have the same utility function. This strategy treats the incomes symmetrically without taking into account the difficulties that some people face in converting income into well-being and freedom. Sen (1982) explores the question of equality of basic capabilities, defined as the different capacity of people to transform the consumption of goods into well-being, well-being being a function of personal fulfilment. Goods possess characteristics for which they are desired, and fulfilment is the concretisation through consumption of that which is desired: it is a different concept, prior to that of utility (which only refers to the satisfaction of the act of consuming).

Besides, the level of household income may not be an adequate indicator for defining household vulnerability to changing economic conditions. The characteristics of the occupational insertion of household members may alter the effect of these changes on household welfare as well as the household’s ability to cope with them. Wage earners will not be on an equal footing with those who own means of production when it comes to coping with economic crises. Workers in managerial positions or highly skilled will face less risks than workers at the lower end of the occupational structure. Clearly, owners of large capital and owners of small- and medium-sized enterprises are not on even ground. The possession of means of production, the characteristics of the occupation and the magnitude of the means of production at one’s disposal are fundamental elements in explaining the living conditions of individuals and households. It is not so much the level of income that is important for a meaningful analysis of the social structure, but rather the way in which it is obtained (Sylos Labini, 1981). Therefore, a stratification criterion that takes seriously into account the occupational insertion of people can contribute important elements to the study of the living conditions of the population. It is in this sense that stratification by social class can become relevant as it allows interpreting the causes of the differential effects of the crisis at different conjunctures (Deledicque et al., 2001; Féliz et al., 2000a, b). The social structure is made up of (objective) positions in the social relations of production (thus conforming to social classes) that are in turn explanatory of the possibilities of access to goods and services, rights and obligations, power and prestige, cultural practices and mould the subjective attitudes of individuals (Sautu, 2020). Class position gives differential opportunities of existence to people and constitute a range of choices and limitations that condition individual and collective action.

Within this framework, we turn to Erik Wright, for whom social classes are constituted by common positions within a particular type of contradictory social relations: the social relations of production (Wright, 1979). From this definition, four characteristics emerge: first, positions imply “empty places” that are “filled” by individuals, which means that it is vital to understand primarily those places and, secondly, who are the specific people who occupy them. Second, positions within relationships imply that the analysis of positions and relationships must coincide. Third, these relations are contradictory: there is an intrinsic antagonism between the constitutive elements of social relations. Finally, contradictory relationships are situated within the sphere of production.

We can decompose the social relations of capitalist production into three interdependent dimensions: control over financial capital (economic property), control over physical capital (order of the productive process) and control of work of other individuals (authority) (Martínez, 1999; Sautu et al., 2020). These dimensions allow us to establish the fundamental class antagonism between capitalists (the social class that holds all these controls) and workers (the one that lacks all of them).

The initial analysis takes place at the highest level of abstraction, shaping a polarised class structure that is a continuum of intermediate positions according to the possession of some of the attributes aforementioned. From this central relationship (capital-labour), we discover other relevant positions: contradictory positions within class social relations. Based on the fundamental classes to which they ascribe, the class nature of these positions is derived since their members participate in the two main camps in an inherently contradictory conflict of interest (Wright, 2015). We must add that basic class positions are not just contradictory but antagonistic: the conditions for the reproduction of one class oppose the conditions of reproduction of the other, while at the same time their existence as classes depend on their simultaneous existence and relationship.

Although Wright gives a leading role to the concept of exploitation in his study of social stratification for advanced societies, the concepts of domination, control, authority and capabilities take on a superlative role. Wright distinguishes four degrees concerning the concept of control (total, partial, minimal and null) to differentiate four contradictory situations according to the degree of control exercised: senior managers, middle managers, technical staff and foremen/supervisors (Martínez, 1999).

Synthetically, for Wright, the social structure would be conformed as follows: (1) the bourgeoisie, made up of traditional capitalists and senior executives; (2) the contradictory positions between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, made up of middle managers, technocrats and supervisors; (3) the proletariat; (4) the contradictory positions between the proletariat and the petty bourgeoisie, made up of semi-autonomous employees; (5) the petty bourgeoisie and (6) the small employers (Wright, 1979, p. 40).

3 Analysing the class structure from survey data

Beyond our differences with Wright’s approach, we believe that for the present study, his contribution is enlightening. This approach allows us to approximate the stratification of classes in Argentina considering the available information, the characteristics of the economy and our main objective: understanding the relationship between the transitional crisis, public policies and existing social differentiation.

The empirical perspective adopted recognises several forerunners. First, the study of Susana Torrado analysing changes in the Argentine social structure between 1945 and 1983 using Census Data (Torrado, 1994). Second, Mariano Féliz and others have used stratification by social class to compare it with income stratification (Féliz et al, 2000a, b) using data compiled by SIEMPRO from the Social Development Survey (EDS) for 1997 in Argentina, providing extensive information on Argentine population in all urban centres with more than 5000 inhabitants. Pablo Ernesto Pérez uses Torrado’s concept of socio-occupational condition to study the labour insertion in young people between 1995 and 2003 (Pérez, 2008). Féliz, López and Fernández and Pérez and Barrera share a common framework for the analysis of income inequality, both using the Permanent Household Survey (EPH) of Argentina (Pérez & Barrera, 2012; Féliz et al, 2012). There are several other recent studies for Argentina and Latin America on class stratification and inequality (Sautu, 2020; Solís et al., 2016; Dalle, 2018; Elbert, 2018). In particular, Sautú and others do several studies on social class structure using a proprietary database for the population of the greater area of Buenos Aires (AMBA) (Sautú et al., 2020). Finally, Elbert used the National Survey on Stratification and Social Mobility in Argentina, produced by CEDEP-UBA, to analyse the relationship between informality and class identity within a modified Wright’s framework (Elbert, 2018).

The empirical operationalisation of classes requires establishing the criteria for constructing a data structure with logical coherence, empirical scope and good use of the available information sources. In this sense, our proposal operationalizes the concept of social classes with data from the EPH of Argentina, defining the social position of households (and its members) as the socio-occupational condition (CSO) of the head of the household (see Appendix 1 for further details).

4 Empirical strategy: social classes and inequality

We begin with the estimation of different inequality measures that describe the situation in each social class, approximated by the CSO. We calculate the income distribution, the cumulative income distribution and the Lorenz curve to first look at inequality and poverty. Then, we resume some inequality information using a Theil Index and calculate mean income using a bootstrapping estimator.

The income distribution allows us to see the ranks and behaviour of income. A flatter curve seems to describe a more unequal situation, in contrast to high asymmetric picks, which are associated with unequal distributions. At the same time, if we want to observe how these peaks are relative to some poverty lines or standard of living, we can use the cumulative distribution curve and see the headcount ratio for different income lines. Then, we compare the initial year 2009 with the last year available with robust information (2019). Furthermore, we use Lorenz curve to analyse whether we need additional criteria in our analysis if the curves intersect. Finally, we expose the behaviour of the mean incomes.Footnote 1

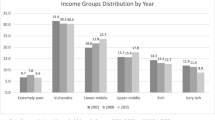

As expected, the general income distribution in the sample is right asymmetric for household per capita income (Fig. 1). Two results stand out in the comparison of results for 2009 and 2019. First, the curve is flatter in 2009 than in 2019; second, the peak of the distribution moves to the left in the same time span. The Pearson coefficient of skewness and the excess kurtosis confirms this observation: in principle, we should expect income inequality to be greater and mean incomes smaller in 2019 than in 2009. This is in line with studies that show that income inequality for Argentina has shown a significant increase since 2015, after several years of reduction in line with Latin America (Tornarolli et al, 2018; Kessler y Assusa, 2020).

Source: The variable used is personal real income monthly expressed in pesos for the 3th quarter of 2020 from EPH. Income is corrected using the methodology of adult equivalent from INDEC (2021). The line on the left (dashed) is the poverty line estimate by INDEC. The line on the right (dash-dot-dash) is the mean income in 2019

Income distribution for Argentina for 4th quarter of 2009 and 2019.

The cumulative income distribution for Argentina is shown in Fig. 2. In comparison with the poverty line and the minimum, living and mobile salary (SMVM by its Spanish acronym) line, the headcount ratio was higher in 2019 (e.g. 35% of people were below the poverty line in 2009, while in 2019, the number reaches 40%, approximately). The fall in real incomes is also evident in this figure: for any income poverty line, there are always more people below it in 2019 than in 2009.

Source: The variable used is personal real income monthly expressed in pesos for the 3th quarter of 2020 from EPH. Income is corrected using the methodology of adult equivalent from INDEC (2021). The line on the left (dashed) is the poverty line estimate by INDEC. The line on the right (dotted) is the mean income in 2019

Cumulative income distribution for Argentina for 4th quarter of 2009 and 2019.

The Lorenz curve for incomes for 2009 and 2019 intersect at several points. Following Lorenz’s criteria, this means that if we use Entropy indexes or the generalised Gini indices, we could obtain conflicting results (Ruiz-Castillo, 2007). In the end, the evaluation of change in inequality depends on our theoretical framework. Thus, it relies on some arbitrary parameters (e.g. aversion to inequality or sensitivity to transferences at the bottom or the top of the income distribution) (Fig. 3).

Lorenz curve income for Argentina for 4th quarter of 2009 and 2019. Source: The variable used is personal real income monthly express in pesos for the 3th from EPH. The income is corrected by the methodology of adult equivalent from INDEC (2021)

Keeping in mind this general information on the income distribution structure, we present our estimations of class structure. Our procedure allowed us to define 12 large groups of CSO (Table 1; Appendix 1). The participation by class is stable throughout the period selected, as shown by Table 1, which compares 2009 with 2019 and also includes mean income estimates by bootstrapping.

In Table 1, we show the mean income by CSO calculated through bootstrapping method using the probability of selection estimates provided by INDEC for income variables. We use this methodology because we can estimate the standard deviation and, in consequence, measurement errors.Footnote 2 INDEC does not publish all the information on stratification to preserve each household’s anonymity in the survey. For this reason, we chose to estimate incomes using a bootstrapping strategy that allows us to obtain income estimates by CSO, and we got a coefficient of variance of less than 10%. As we can see from Fig. 4, real incomes for every CSO decrease between 2009 and 2019.

Source: The mean income was calculated using bootstrapping method. The monthly income is in real terms, expressed in pesos of the 3rd quarter of 2020. Income is represented by the income from the main occupation of the head’s household, which is used to determine its CSO (see Appendix 1 for further information). For the estimation results, we use R-Statistic

Real mean incomes.

The popular classes are the only group whose income participation is lower than their participation in the total population (Table 2), reflecting that their mean income is very low in relationship with the rest of the strata.

We estimate inequality within and between CSO through an Entropy Index (Table 3). We use a parameter equal to cero (Goerlich & Villar, 2009); this is the so-called Theil index with weights based on population share. We select a parameter equal to zero because we assume that whatever transfer between individuals has the same impact on the index throughout the income distribution (Pigou-Dalton transfers). If we want to compare two distributions, which is the case here, a change on the top or the bottom of the income distribution has the same importance in the index. The weights selected represent the share of each CSO in the population. In other words, we choose the parameter of no aversion to inequality and the weights not affected by income distribution (Goerlich & Villar, 2009).

The results reflect that the contribution to total inequality is greater for salaried operative fractions. The principal reason for this is their relatively high weight in the total population. The Theil index within-group (Tw) inequality falls between 2009 and 2019, but inequality grows between groups (Tb). Although mean incomes fall in the period, relative differences increase. However, for some groups, their contribution to inequality grew in the period: salaried technician, autonomous worker with means of production, salaried professional and chief/supervision (salaried) show an increase in their within-group inequality.

This result seems to be in line with Dalle’s analysis that shows that despite the growth in structural opportunities for the middle classes, there is a persistent inequality in the chances for social mobility across the class structure (Dalle, 2018). Concurrently, Solis (2016b) in his study on the correspondence between distributional inequality and social mobility shows a pathway in which inequality of opportunity operates. Using a class stratification that follows Erikson and Goldthorpe, they study the movement between generations within these social structures. They show that upper classes present greater barriers to social mobility, and this phenomenon is stronger for Argentina and México, while the European social structure has relatively more people in the upper classes and higher percentages of skilled workers. They also highlight as a phenomenon the existence of social fluidity within the rigid class structure, and generally observed in the middle and lower classes. Other studies that delve into historical terms of regional differences, such as that of Álvarez and Deza 2012), demonstrate the regional limits of social fluidity within Argentina.

5 Inequality in and through the transitional crisis in Argentina

In the following pages, we analyse how the crisis in Argentina from 2009 onwards has affected the class structure and especially the different strata within it.

Before starting the transitional crisis, the Argentine economy showed an expansionary dynamic for at least five years (2003 In the end, the evaluation 2009) (Fig. 5).

Several elements explain this. At the international level, the sustained recovery in the prices of export commodities is driven by China’s irruption in the capitalist world market. These created the conditions for producing and appropriating a significant mass of land rent that fed the local capital accumulation process (Féliz, 2014). At the local level, a combination of several elements allowed the use of these international conditions (F. Cantamutto & Wainer, 2013). On the one hand, the neoliberal crisis (1998–2002) had led to the default on an important fraction of the public debt, setting up conditions for decoupling the capital accumulation process from the demands of finance capital for several years (Féliz, 2015). On the other hand, the crisis altered the value relationships in favour of capital: the rate of profit of large capital recovered rapidly between 2002 and 2008, facilitating the recovery of investment in constant capital, the increase in employment and some recovery of wages. The debt default and the devaluation of the labour force employed in the public sector created favourable room for a process of fiscal expansion that leveraged an increase in domestic aggregate demand (F. J. Cantamutto & Castiglioni, 2020).

The global crisis of 2007–2009 conspired to accelerate certain contradictions that vernacular capitalism was accumulating. On the one hand, it accelerated the appreciation of local currency relative to the dollar. We also witnessed the recovery of wages in the private sector and the weak increase in relative labour productivity, the deterioration of the economy’s external competitiveness and the increase in the balance of payment deficit. The global crisis put a brake on the increase in international prices and placed a ceiling on ground rent. The subsequent 5-year period (2009–2014) led to stagnation and macroeconomic instability. This process was experienced in the whole of Latin America with particularities pertaining to the economic and social structure of each country (Benza and Kessler, 2021).

After the recovery of 2009–2010, macroeconomic imbalances (fiscal, external and inflation) were accentuated, particularly from 2011 and growth stagnated. While between 2004 and 2010, the GDP grew 37%, between 2010 and 2017, it only grew 7.6% (falling significantly in per capita terms). This links to the fact that, after reaching its peak in 2006, the rate of profit of large capitals fell sharply to 2017 (Fig. 6).

The consolidation of the ruling alliance marked the previous stage of relative economic bonanza. As Elbert and Pérez stress, the whole of Latin America experienced a period of relative political stability and economic growth (Elbert and Pérez, 2018: 5).

During the presidency of Néstor C. Kirchner (NK) (2003–2007) and the first of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (CFK) (2007–2011), an important fraction of the popular sectors received a set of social policies and labour that allowed some economic spill. However, already at the end of the NK presidency, an increasing number of conflicts began to be observed within fractions of the popular classes, whose demands were not being answered or were only postponed (Féliz, 2012). Within the framework of a dependent economy (Marini, 2015) such as Argentina (Féliz, 2019), the demands for economic integration were rapidly running up against insurmountable limits. On the other hand, the global crisis catalysed local opposition forces that gradually articulated politically (Féliz, 2016a).

The hegemonic project began to fracture, as it was unable to displace or overcome the barriers that it had itself composed. The global crisis only accelerated the transition process that implied an attempt at a step-by-step adjustment, described as ‘fine tuning’ in late 2011 (Féliz, 2019). However, it quickly became a succession of reforms that simultaneously sought to consolidate political hegemony in a context of stagnation and recreate the conditions for economic growth.

Between 2009 and 2014, the popular classes saw their incomes begin to falter and their employment conditions deteriorate (Fig. 7). The employment rate began to fall after having reached a peak in 2011.

As aggregate employment begins to stagnate, some fractions within classes suffer to a greater extent than others (Table 4).

The less-skilled fractions of the salaried workforce (operational and low-skilled) and the self-employed without access to means of production suffered a significant hit in their employment levels. In the latter case, the deterioration in employment between 2009 and 2014 is almost 20%.

The slowdown and growing instability of the economy are beginning to create pressures for deepening the conditions of super-exploitation of the labour force; in dependent economies, capital tends to pay wages below the cost of reproducing the labour force for a significant portion of the working class (Féliz, 2019; Marini, 2015).

During a crisis, this process accelerates and deepens. In fact, precarisation of labour (a form of expression of super-exploitation) has been shown to be a fluid condition across Argentina’s working class (Elbert, 2018). There is a debate on how much this process implies the dissolution of the boundaries within the working class (Elbert, 2018; Portes and Hoffman, 2003).

Despite the expansive policies attempted during the second government of CFK, the pressure on the class that lives from work — to use the image proposed by Antunes (Antunes, 2003) — was increased. The government multiplied and extended some programs that seek to compensate — albeit partially — the growing insufficiency of income and employment (Féliz, 2016a). On the one hand, the Universal Child Allowance is created, generalising (but not universalising) a sort of unconditional cash transfer to families with children. On the other hand, the State extended their credit programs to the popular sectors, including families of retirees and pensioners. These programs helped reduce income inequality, especially by drastically increasing the income of the lower fractions within the working classes: by late 2017, lower income populations (mostly lower fractions of the working classes) generally received 50% of their money income from non-labour sources (thus, from State transfers); for upper-income fractions, this proportion hover at around 20% (INDEC, 2017: 9).

Despite these compensation policies, their living conditions continued to deteriorate as the macroeconomy would not pick up. Social conflicts multiplied between 2014 and 2015, with one immediate political consequence: the ruling coalition of President CFK shattered. In 2015, this alliance was defeated in national elections by a pro-business right-wing coalition, leading Mauricio Macri to the presidency (Féliz, 2016a).

With the change of government at the end of 2015, the ‘correction’ of macroeconomic imbalances accelerated. The mass of surplus-value fell steadily since 2009, with a slight recovery around 2010 (Fig. 8), despite efforts to promote countercyclical policies that increase the fiscal deficit (Féliz, 2018). The deep dive of the amount of surplus value produced helps explain that through the crisis, managers, supervisors and small business owners were also hit hard by the crisis (Table 4).

Source: Own estimate based on INDEC databases. Seasonally adjusted series of GDP and consumption, base 2004. The mass of surplus-value is approximated through the difference between GDP and total consumption. Although, following Kalecki, capitalist consumption is part of the mass of surplus-value, we cannot estimate this precisely

Mass of surplus value (GDP-Consumption). Argentina, 2003–2017

President Mauricio Macri’s (2015–2019) government promoted a policy that seeks to accelerate economic adjustment, attempting to recreate conditions favourable to capital accumulation and economic growth (Féliz, 2018). Simultaneously, it tried to consolidate its political hegemony. With this last objective in mind, the adjustment process went on at “baby steps” while fiscal imbalances were taken care of through an accelerated foreign public indebtedness. During this stage, the pressure on real wages increased to the extent that the minimum wage policy began to be used as a nominal anchor rather than as a wage floor (Fig. 9).

Source: Own estimate on the databases of INDEC and the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Security (MTEySS). The SMVM is deflated with a spliced price index based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) of Greater Buenos Aires, the provinces of San Luis and Santa Fé, the National CPI series. For further information on the question, contact the authors

Minimum, living, and mobile salary (SMVM) in constant pesos (real terms). Argentina, 2003–2021

The government’s SMVM was adjusted at a slower pace than inflation, which was accelerating. The result was a 20% fall in the SMVM in real terms between 2015 and 2018. Instead of putting a floor on wages, labour policy balanced the distributional equation in favour of capital. Low-qualification salaried fractions, at the bottom of the registered fractions of the salaried working class and whose wages tend to be regulated by the value of the SMVM, were hit the hardest by this dynamic between 2017 and 2019 (Table 4).

The acceleration of the crisis required a change in strategy. The previous government attempted to ‘fine tune’ economic imbalances. On the contrary, Macri’s government pushed for a rapid adjustment process in some variables, devaluing the exchange rate and violently raising prices for public services such as electricity, gas and water. Regarding the structural reforms that big capital was demanding (such as fiscal adjustment, labour reform or social security reform), the new government could only advance slowly during its first 2 years (Piva, 2018).

Until the end of 2017, the debt multiplied rapidly. Total public debt jumped from $240 billion in 2015 to more than $320 billion in 2017. However, at the beginning of 2018, multibillion-dollar financing from big international finance capital was cut off abruptly. The bet that these sectors made for a government that a priori was more akin to their interests went bust.

The impossibility of continuing with the adjustment process with abundant financing for the existing macroeconomic imbalances disarticulated the expanded reproduction of capital. As their patience exhausted, the dominant fractions somersaulted forward into the void. The flight of capital accelerated, and the crisis deepened. The resistance of the popular classes to adjustment broke down.

Economic activity collapsed at the pace of the violent devaluation of the national currency against the dollar. The result was a jump in the inflation rate that brutally devalued popular incomes. While until 2017, the participation of the income of the working classes (salaried workers and autonomous) remained fairly stable, from then on, there was a marked reduction (Table 5).

Between 2009 and 2017, there is a significant growth in average household income in all class fractions within the working classes. On the contrary, between 2017 and 2019, there is a generalised collapse (except for self-employed professionals). With the aforementioned limits, we can see that the capitalist fraction was the least hit by the 2017–2019 crisis in Argentina. This differential effect might be related to the general process of concentration of property and wealth (not properly measured by the EPH). This process has been registered across the world and particularly in Latin America in the past decades (Piketty, 2014; Benza and Kessler 2021) and provides upper classes a ‘buffer’ to weather the crisis or even profit from them.

We can see that increasing inequality as the crisis loomed is partly related to rapidly falling incomes for the working fractions within the labouring classes, in comparison with the so-called ‘middle classes’ (that in our scheme could include mainly professionals and supervisors and parts of the non-professional autonomous workers with means of production). The deterioration process tended to consolidate a massive impoverishment of the popular classes. In Table 6, we observe the differences between classes in the population under the poverty line calculated by INDEC.

It is interesting to note that this middle class became fierce critics of the progressive governments in Latin America (Benza and Kessler 2021), even when their situation did not deteriorate as much as for the lower fractions of the working classes. In the case of Argentina, these later fractions were dramatically hit by the acceleration of the crisis and — in many cases — diverted their political support away from kirchnerism in the 2015 election (Féliz, 2016a).

While economic growth stagnated, popular resistance to adjustment and compensatory policies made it possible to reduce income poverty. However, a breakdown occurred violently after 2017. In particular, among domestic service workers (primarily women), low-income workers qualified and autonomous (mostly male), the poverty rate reached levels that are unheard of in Argentina’s history. It is noticeable that even as social policies (and, especially, cash-transfer programs) multiplied and expanded in Argentina since the early 2000 (Schipani et al, 2021), they were unable to avoid the rapid deterioration of incomes and the increasing inequality as the crisis advanced. The beneficiaries of social policies could only very partially compensate for the blow to their incomes.

In the same way, the crisis impacted the popular classes, intensifying inequality (Table 7). The Foster-Greer-Thorbecke (FGT) indicators account for depth or distance from the poverty line ((FGT-1) and inequality within poverty (FGT-2).

The impoverishment of salaried workers (31.9% of the total, that is, 3.95% of a total of 12.39%) and self-employed with means of production (25,5% of the total) explains most income poverty (LP-09) in 2009. In 2019, the first ones represented 32.2% of total poverty incidence, while the second group represented 26.5%.

The transitional crisis hit the popular classes as a whole: the poor are getting poorer and poorer; FGT (1) goes from 4.19 to 15.23% in the decade. At the same time, inequality within the poor; FGT (2) increased from 2.15 to 8.18% between 2009 and 2019. Table 5 shows that within the working class, poverty is concentrated and increased among those fractions that do not have means of production or do not have professional tasks (such as autonomous labourers or operative or low qualification salaried workers).

6 Conclusions

This paper seeks to analyse the distributional dynamics through the transitional crisis in Argentina between 2009 and 2019. We approach this study from an empirical strategy that allows us to recover the perspective of social class stratification from the periodic data of an official survey of households and individuals. The Permanent Household Survey (Encuesta Permanente de Hogares, EPH) is a continuous survey rarely used within this approach and for this particular goal. Our proposal allows us to construct social strata based on the insertion of households in the labour market. The Socio-Occupational Condition (CSO) becomes the critical variable for this task.

We give a brief description of the general results of this stratification in terms of income inequality. Our data confirm a significant increase in inequality from 2009 to 2019 (Benza and Kessler, 2021), showing a greater impact in the lower strata within the social structure (especially, in the bottom fractions of the salaried workers and the property-less fractions within the autonomous workers).

We can see how our stratification strategy allows us to carry out a novel analysis of the economic crisis that Argentina has been going through for more than a decade. Our study provides support to the importance of class analysis for empirical research on the impact of economic policies and macroeconomic dynamics, complementing studies that stress the structural importance of class structure for the study of social mobility and social identity (Sautú, 2020; Solís, 2016a; Elbert, 2018).

Then, we show how the macroeconomic dimensions of the crisis have had a differentiated impact on the different class fractions. For example, professional fractions within the working class fared much better (in an impossible context) than most workers at the bottom of the distribution. We also show how state policies, chiefly labour and social policies can have differential effects within the class structure. There is still much work to be done to comprehend the class nature of economic policy and its particular class-biased effects.

The general conclusion is that while the crisis has produced a generalised shock to the incomes of different class fractions, the particular evolution in each case is different even if within a general downward trend. On the other hand, we show how the evolution of income inequality at the aggregate level hides different changes within the social structure.

This study opens a novel field of empirical research that can take advantage of the information available from public sources that appear periodically to develop exhaustive analysis of the distributive dynamics at various levels and the impact of state policies in this regard. Future studies will provide new information regarding how labour, social and macroeconomic policies can have particular effects and biases on different population strata.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Notes

For these analyses, we use the income weights estimated by INDEC (INDEC, 2003).

Some errors not pertaining to the sampling process will remain (e.g. the none/under-responses regarding household income or the fact that it is challenging to include households at the bottom and top of the income distribution). INDEC uses different techniques to correct these biases on income weights (INDEC, 2019).

References

Álvarez B, Deza MFC (2012) La Movilidad Social En Tucumán, Argentina, 1869–1895. América Latina En La Historia Económica 20(1):126. https://doi.org/10.18232/alhe.v20i1.510

Antunes R (2003). ¿Adiós al trabajo? Ensayo sobre las metamorfosis y el rol central del mundo del trabajo. Herramienta Ediciones.

Atkinson AB (1970) On the measurement of inequality. J Econ Theory 2(3):244–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(70)90039-6

Benza G, Kessler G (2021) La ¿nueva? Estructura Social de América Latina. Cambios y Persistencias Después de La Ola de Gobiernos Progresistas, 1ra edn. Siglo XXI Editores, Buenos Aires

Bowles S, Gintis H, Osborne M 2000. The determinants of earnings: skills, preferences, and schoolinG. Working Paper. 87. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts.

Cantamutto FJ, Castiglioni L (2020). El problema de la deuda argentina (p. 11). IIESS.

Cantamutto F, Wainer A (2013). Economía política de la Convertibilidad. Disputa de intereses y cambio de régimen. Capital Intelectual.

Castrosin MP, Venturi Grosso L. (2016). Descomposición del gini por fuentes de ingreso: Evidencia empírica para Argentina 2003–2013 (Documento de Trabajo No. 197; Documento de Trabajo, p. 22). CEDLAS. https://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar/wp/doc-cedlas197-pdf/

Dalle P (2018) Climbing up a steeper staircase: intergenerational class mobility across birth cohorts in Argentina (2003–2010). Res Soc Stratif Mobil. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2017.12.002

Deledicque, Luciana Melina, Mariano Féliz, Alejandro Pablo Sergio, and María Luciana Storti (2001). ‘De Cómo Evitar Pasar de Vulnerables a Pobres. Estrategias Familiares Frente a La Incertidumbre En El Mercado de Trabajo’. P. 30 in XXIII Congreso de la Asociación Latinoamericana de Sociología (ALAS). Antigua (Guatemala): Asociación Latinoamericana de Sociología.

Elbert R, Pérez P (2018) The identity of class in Latin America: objective class position and subjective class identification in Argentina and Chile (2009). Curr Sociol 66(5):724–747. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392117749685

Elbert R (2018) Informality, class structure, and class identity in contemporary Argentina. Lat Am Perspect 45(1):47–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X17730560

Féliz M (2012) Neo-developmentalism: beyond Neoliberalism? Capitalist crisis and Argentina’s development since the 1990s. Hist Mater 20(2):105–123. https://doi.org/10.1163/1569206X-12341246

Féliz M (2014) The Neo-developmentalism alternative: capitalist crisis, popular movements, and economic development in Argentina since the 90s. In: Spronk S, Webber JR (eds) Crisis and Contradiction: Marxist Perspectives on Latin American in the Global Economy. Brill Press, pp 52–72

Féliz M (2015) Limits and barriers of neodevelopmentalism: lessons from Argentina’s experience, 2003–2011. Rev Rad Polit Econ 47(1):70–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0486613413518729

Féliz M (2016) Till death do as apart? Kirchnerism, neodevelopmentalism and the struggle for hegemony in Argentina, 2003–2015. In: Schmitt I (ed) The Three Worlds of Social Democracy: A Global View from the Heartlands to the Periphery. Pluto Press, pp 91–106

Féliz M (2016) Transformations in Argentina’s capitalist development since the Neoliberal Age: limits and possibilities of a peripheral development strategy. World Rev Political Econ 7(3):350–362

Féliz M. (2018). Cambiemos: Entre la reforma y la crisis en el capitalismo dependiente. In ANUARIO EDI 2018. Capitalismo argentino: ¿una vez más en la encrucijada? (1ra ed., pp. 67–75). Economistas de Izquierda (EDI) / Oficina de Buenos Aires de la Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo. https://rosaluxspba.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Anuario-EDI-2018-para-web.pdf

Féliz M (2019) Neodevelopmentalism and dependency in twenty-first-century Argentina: insights from the work of Ruy Mauro Marini. Lat Am Perspect 46(1):105–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X18806588

Féliz M, Millón ME (2021). Estructura de clases y crisis transicional en Argentina. In G. Felix (Ed.), Trabalho e Trabalhadores na América Latina e Caribe.

Féliz M, Deledicque LM, Sergio AP (2000a, 11–1/12). Análisis metodológico de la estratificación social desde las perspectivas sociológica y económica. 1ras Jornadas de Sociología, La Plata.

Féliz M, López E, Lisandro F (2012). Estructura de clase, distribución del ingreso y políticas públicas. Una aproximación al caso argentino en la etapa post-neoliberal. In M. Féliz (Ed.), Más allá del individuo. Clases sociales, transformaciones económicas y políticas estatales en la argentina contemporánea (pp. 203–224). Editorial El Colectivo.

Féliz M, Deledicque LM, Sergio AP (2000b). Análisis Metodológico de La Estratificación Social Desde Las Perspectivas Sociológica y Económica. La Plata: Departamento de Sociología :: FaHCE/UNLP.

Goerlich FJ., Villar A (2009). Desigualdad y bienestar social: De la teoría a la práctica. Fundación BBVA.

Gordon D. M., Edwards R., Reich M. (1994). Long swings and stages of capitalism. In D. M. Kotz, T. McDonough, & M. Reich (Eds.), Social structures of accumulation. The political economy of growth and crisis (1ra ed., pp. 11–28). Cambridge University Press.

INDEC. (2003). Encuesta Permanente de Hogares. Actualización del diseño de sus muestras. 1974–2003. INDEC. https://www.indec.gob.ar/ftp/cuadros/sociedad/eph_muestras_74-03.pdf

INDEC. (2019). Evolución de la distribución del ingreso (EPH). Cuarto trimestre de 2019 (Informes Técnicos 4(2); Trabajo e Ingresos). INDEC. https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/ingresos_4trim19631D7F2C43.pdf

INDEC. (2021). Incidencia de la pobreza y la indigencia en 31 aglomerados urbanos. Segundo semestre de 2020 (Informes Técnicos 5(4); Condiciones de Vida). INDEC. https://www.indec.gob.ar/uploads/informesdeprensa/eph_pobreza_02_2082FA92E916.pdf

INDEC (2017). Evolución de La Distribución Del Ingreso (EPH). Tercer Trimestre de 2017. Informes técnicos. 1(245)/1(11). Buenos Aires: INDEC.

Jaccoud F, Arakaki A, Monteforte E, Pacífico L, Graña J, Kennedy D (2015) Estructura productiva y reproducción de la fuerza de trabajo: La vigencia de los limitantes estructurales de la economía argentina. Cuadernos De Economía Crítica 1(2):79–112

Kessler,G, Gonzalo A (2020). Pobreza, Desigualdad y Exclusión Social. Informe. Buenos Aires: Jefatura de Gabinete de Ministros.

Marini RM (2015). América Latina, dependencia y globalización / Ruy Mauro Marini (C. E. Martins, Ed.). Siglo XXI Editores / CLACSO. https://www.clacso.org.ar/antologias/detalle.php?id_libro=1034

Martínez R. (1999). Estructura social y estratificación. Reflexiones sobre las desigualdades sociales. (1ra ed.). Miño y Dávila Editores.

Pérez P. E. (2008). La inserción ocupacional de los jóvenes en un contexto de desempleo masivo. El caso argentino entre 1995 y 2003 (1ra ed.). Miño y Dávila Editores.

Pérez P. E., Barrera F. (2012). Estructura de clases, inserción laboral y desigualdad en la post-convertibilidad. In M. Féliz (Ed.), Más allá del individuo. Clases sociales, transformaciones económicas y políticas estatales en la argentina contemporánea (pp. 225–249). Editorial El Colectivo.

Piketty T (2014). Capital in the twenty-first century. Cambridge / Mass :: London / UK: Belknap Press.

Piva A. (2018). Estancamiento, inestabilidad cambiaria y tendencia al ajuste: La vigencia del bloqueo a la ofensiva capitalista contra el trabajo. In ANUARIO EDI 2018. Capitalismo argentino: ¿una vez más en la encrucijada? (1ra ed., pp. 32–37). Economistas de Izquierda (EDI) / Oficina de Buenos Aires de la Fundación Rosa Luxemburgo. https://rosaluxspba.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Anuario-EDI-2018-para-web.pdf

Portes A, Hoffman K (2003) Latin American Class structures: their composition and change during the Neoliberal Era. Lat Am Res Rev 38(1):41–82

Ravallion M. (1992). Poverty comparisons: a guide to concepts and methods (Working Paper No. 88; Living Standard Measurement Study, p. 123). Banco Mundial. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/290531468766493135/pdf/multi-page.pdf

Ruiz-Castillo J. (2007). La medición de la desigualdad de la renta: Una revisión de la literatura (Documento de Trabajo No. 7–1; Serie de Economía, p. 42). Universidad Carlos III de Madrid :: Departamento de Economía. https://docs.google.com/viewerng/viewer?url=https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/bitstream/handle/10016/617/de070201.pdf

Sautu R, Boniolo P, Dalle P, Elbert R (eds) (2020) El análisis de clases sociales. Pensando la movilidad social, la residencia, los lazos sociales, la identidad y la agencia, 1ra edn. CLACSO, Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani

Sautu R (2020). ‘Una Escala Para Ordenar Ocupaciones.’ Pp. 327–42 in El análisis de clases sociales. Pensando la movilidad social, la residencia, los lazos sociales, la identidad y la agencia, edited by R. Sautu, P. Boniolo, P. Dalle, and R. Elbert. Buenos Aires: Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani :: CLACSO.

Schipani A, Zarazaga R, Forlino L (2021). Mapa de Las Políticas Sociales En La Argentina. Aportes Para Un Sistema de Protección Social Más Justo y Eficiente. Buenos Aires: CIAS :: Fundar.

Sen AK (1982) Choice, welfare and measurement. Blackwell, Oxford

Shaikh A. (2016). Capitalism. Competition, conflict, crises. Oxford :: Oxford University Press.

Solís P. 2016a. ‘Algunos Rasgos Distintivos de La Estratificación y Movilidad de Clase En América Latina: Síntesis y Tareas Pendientes’. Pp. 477–98 in Y, sin embargo, se mueve... Estratificación social y movilidad intergeneracional de clase en América Latina, edited by P. Solís and M. Boado. México: El Colegio de México :: Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesis.

Solís P. 2016b. ‘Movilidad Intergeneracional de Clase En América Latina: Una Perspectiva Comparativa’. Pp. 75–132 in Y, sin embargo, se mueve... Estratificación social y movilidad intergeneracional de clase en América Latina, edited by P. Solís and M. Boado. México: El Colegio de México :: Centro de Estudios Espinosa Yglesis.

Sylos Labini P (1981) Ensayo Sobre Las Clases Sociales. Ediciones Península, Barcelona

Tornarolli L, Matías C, Galeano L (2018). Income distribution in Latin America. The evolution in the last 20 years: a global approach. Documento de Trabajo. 234. La Plata: CEDLAS :: UNLP.

Torrado S. (1994). Estructura social de la Argentina: 1945–1983 (2da ed.). Ediciones De La Flor.

Torrado S. (1998). Familiar y diferenciación social (1ra ed.). EUDEBA.

Wright EO. (1979). Class structure and income determination (1ra ed.). Academic Press.

Wright EO. (2015). Understanding class. Verso Books.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Féliz, M., Emilia Millón, M. Crisis and class inequality in Argentina: a new analysis using household survey data. Rev Evol Polit Econ 3, 405–433 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00080-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00080-9