Abstract

The Future of Affective Science Special Issues illuminate where the field of Affective Science is headed in coming years, highlighting exciting new directions for research. Many of the articles in the issues emphasized the importance of studying emotion regulation, and specifically, social emotion regulation. This commentary draws on these articles to argue that future research needs to more concretely focus on the social aspects of social emotion regulation, which have been underexplored in affective science. Specifically, we discuss the importance of focusing on social goals, strategies and tactics, and outcomes relevant to social emotion regulation interactions, more closely considering these processes for all individuals involved. To do so, we draw on research from neighboring subdisciplines of psychology that have focused on the social aspects of interactions. Moreover, we underscore the need to better integrate components of the process model of social emotion regulation and approach empirical inquiry more holistically, in turn illuminating how piecemeal investigations of these processes might lead to an incomplete or incorrect understanding of social emotion regulation. We hope this commentary supplements the research in the special issues, further highlighting ways to advance the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

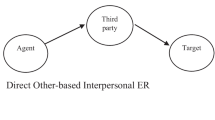

The Future of Affective Science Special Issues highlight exciting new directions for research. As participants in the field, we write to share our thoughts about topics we see as important but have been underexplored in the literature thus far, with an emphasis on opportunities for greater interconnection across research areas. We focus primarily on the social side of emotion regulation, as this is a relatively new and fast-growing area of interest (Petrova & Gross, 2023; Simmons et al., 2023). We use the term social emotion regulation (Coan et al., 2006; Beckes & Coan, 2015), rather than other terms in current usage (such as interpersonal emotion regulation, e.g., Zaki & Williams, 2013; see DiGiovanni, He & Ochsner for expanded discussion of terminological usage), because it inclusively refers to the growing variety of situations being studied where interactions between two or more individuals regulate the emotions of one or more interaction partners. Defined thusly, social regulation can occur in dyadic interactions (Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015) as well as group interactions, either in person (Goldenberg et al., 2016) or online (Dore et al., 2017).

Our response to the special issues is informed by a process model of social emotion regulation (SER; Reeck et al., 2016), which considers the multitude of goals that guide regulation, the strategies and tactics used to regulate, and the outcomes of the regulatory process. In this commentary, we hope to begin the discussion on fruitful areas for future research, highlighting new ways forward that emphasize the social nature of social emotion regulation and taking an integrative approach across fields of psychological science (DiGiovanni et al., in prep). Table 1 below summarizes key discussion points.

A Closer Examination of Goals in Social Emotion Regulation

Theoretical models have long posited that self-regulation is guided by goals (Carver & Scheier, 2012; Miller et al., 1960). Although multiple special issue authors highlighted the importance of understanding the goals that guide emotion regulation (e.g., Becker & Bernecker, 2023; Petrova & Gross, 2023; Tran et al., 2023), to date, most relevant studies have considered only goals that are affective or hedonic. Yet, emotion regulation—especially social emotion regulation—may also be guided by social goals, which reflect a desire to influence the nature and/or quality of relationships and social contexts (Tamir, 2016; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; Tamir, 2016; Springstein & English, 2024). Some theoretical (Niven, 2017; Dixon-Gordon et al., 2015; English & Growney, 2021; Springstein & English, 2024) and empirical (Liu et al., 2021; Kalokerinos et al., 2017) work has begun considering social goals, but relevant research is still scarce. Going forward, we encourage emotion regulation scholars to more clearly delineate and define different types of social goals that may motivate or guide emotion regulation (see Table 1), and, as elaborated in the next section, study when (e.g., in what situations) individuals use social regulation vs. self-regulation to attain social goals.

In particular, future work may look to examine how prosocial goals—such as seeking to enhance intimacy in a relationship—not only serve social functions, but also influence affective outcomes and may dovetail—or conflict with—affective goals (Kruglanski et al., 2015). For example, a supportive individual may have a prosocial goal to enhance closeness with a new romantic partner, while simultaneously possessing an affective goal to feel positive emotions, and these goals may not align. To enhance relationship closeness, an individual may need to support their struggling partner during a particularly stressful time, which may result in the support provider feeling increased negative emotions through the process of stress contagion. Although this may undermine the support provider’s affective goal, it may nevertheless foster greater closeness via enhanced responsiveness (e.g., Balzarini et al., 2023).

In addition to balancing multiple types of goals, relational contexts may also require assessments of how personal goals (mis)align with a partner’s goals (Fitzsimons et al., 2015). For example, an individual may see their friend is upset and want to cheer them up, but also realize their friend does not want that and instead wants to vent about the issues, without feeling they are being explicitly supported (Zee & Bolger, 2019). A regulator’s decision whether and when to offer social regulatory support must take into account not just their own goals to be supportive and/or happy, but also their partner’s goals to express emotion and/or maintain regulatory independence. Taken together, this highlights how a multiplicity of goals—and their relative prioritization—should be examined both within and between individuals.

Examining Social Emotion Regulation Strategies and Tactics

Various authors highlighted the need for future research to further examine how, why, and with what affective consequences, individuals select particular emotion regulation strategies and tactics (e.g., DiGirolamo et al., 2023; Petrova & Gross, 2023). Although this question has been heavily studied in research on self-regulation of emotion (e.g., DiGirolamo et al., 2023; McRae et al., 2012), fewer papers have examined the why, when, and how of strategy and tactic selection in social contexts, as well as the resulting outcomes. Papers making this connection are emerging, including one showing that social regulators select different strategies depending on the specific emotion they perceive targets to be experiencing (Shu et al., 2021). This work highlights how targets’ emotions impact social regulation tactic selection and success.

Connecting these ideas back to the assessment of regulatory goals in general—and prosocial goals in particular—future work may look to study under what conditions social goals lead individuals to engage in self vs. social emotion regulation and what specific strategies and tactics are employed. For example, although recent work has demonstrated that prosocial goals (e.g., to build or maintain relationships) are a primary reason individuals choose to engage in social emotion regulation (Tran et al., 2024), there may also be times that self-regulation strategies (e.g., suppressing the expression of personal distress when helping an upset friend) are the best means of attaining prosocial goals. Future work may delve deeper into understanding differences and similarities between when and why social versus self-regulation of emotion is chosen, capitalizing on dyadic methods to explore tactic selection and implementation and—as discussed below—resulting outcomes for regulators and targets (e.g., Gleason et al., 2003; DiGiovanni et al., 2023; Park et al., 2023; Peters et al., 2024).

Assessing Multiple Types of Outcomes Relevant to Emotion Regulation

Finally, with respect to the outcomes of emotion regulation, we make a point parallel to our points about goals and strategies and tactics. For many instances of emotion regulation, and especially those that involve social regulatory interactions, it will be important to understand both affective and social outcomes for all individuals involved, whether they acted as a regulator providing support to others or as a target that received support (or both). In general, there is an underemphasis on the ways that social emotion regulation impacts social outcomes. Yet, as social beings whose actions have implications for those around us, it is imperative that we consider how both self-regulation and social regulation influences not just our own affect, but also our relationships and feelings towards others. Of particular importance may be prosocial outcomes, such as those that are associated with feelings about the interaction partner (i.e., liking of the partner).

For example, emotion regulation research could assess prosocial outcomes such as physical and emotional intimacy, feelings of support, perceived partner responsiveness, and gratitude (e.g., Algoe, 2012; Cornelius et al., 2022; Feeney & Collins, 2015; Gleason et al., 2008; Girme et al., 2013; Reis et al., 2004; Rossignac-Milon et al., 2021; Visserman et al., 2018). Such outcomes have been long studied in relationship science, and their inclusion in future work would enable affective scientists to understand the rich and interconnected nature of affective and social outcomes resulting from emotion regulatory processes. In related disciplines, work on social support (Gleason et al., 2008) and co-rumination (DiGiovanni et al., 2021) provide examples of how such integration can be useful by providing insight into how affective and social outcomes can be intrinsically related.

Putting the Pieces Together

In the paragraphs above, we hope to have highlighted the potential value of examining understudied topics in the study of social emotion regulation (i.e., social goals, the social nature of strategy and tactic implementation, and social outcomes). That said, it is important to emphasize that studying any one aspect of self- or social emotion regulation in isolation gives us an incomplete picture of how regulation unfolds in everyday life—and many important questions remain about why, when, and how we engage in self vs. social regulation. As such, future work on social emotion regulation can aim to take a personalized approach (see Doré et al., 2016), whereby outcomes are assessed as resulting from unique interactions between person-level variables, situations, and strategies selected and implemented. Without explicitly examining heterogeneity in what strategies work for particular individuals in particular situations (e.g., DiGiovanni et al., 2021; Sahi et al., 2023), we will have an incomplete, or at worst, incorrect, understanding of social emotion regulation.

Conclusion

Taken together, the special issues highlighted a number of fruitful new directions for affective science, and emotion regulation more specifically (summarized in Table 1). We are excited to be participants in these new directions and look forward to the future of the field. Towards this end, we have argued that future work could increasingly (1) emphasize the expressly social goals, strategies/tactics, and outcomes of social emotion regulation and (2) more holistically study the interactions among all elements of the regulatory process. These suggestions dovetail with research programs prioritized by granting agencies (Simmons et al., 2023) and may also help reveal the ways in which social and affective variables have implications for individual, relational, and societal well-being.

References

Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469.

Balzarini, R. N., Muise, A., Zoppolat, G., Di Bartolomeo, A., Rodrigues, D. L., Alonso-Ferres, M., ... & Slatcher, R. B. (2023). Love in the time of COVID: Perceived partner responsiveness buffers people from lower relationship quality associated with COVID-related stressors. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(3), 342–355.

Becker, D., & Bernecker, K. (2023). The role of hedonic goal pursuit in self-control and self-regulation: Is pleasure the problem or part of the solution? Affective Science, 4(3), 470–474.

Beckes, L., & Coan, J. A. (2015). Relationship neuroscience. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. A. Simpson, & J. F. Dovidio (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Vol. 3. Interpersonal relations (pp. 119–149). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14344-005

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2012). Attention and self-regulation: A control-theory approach to human behavior. Springer Science & Business Media.

Coan, J. A., Schaefer, H. S., & Davidson, R. J. (2006). Lending a hand: Social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science, 17(12), 1032–1039.

Cornelius, T., DiGiovanni, A., Scott, A. W., & Bolger, N. (2022). COVID-19 distress and interdependence of daily emotional intimacy, physical intimacy, and loneliness in cohabiting couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(12), 3638–3659.

DiGiovanni, A. M., Cornelius, T., & Bolger, N. (2023). Decomposing variance in co-rumination using dyadic daily diary data. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 14(5),636–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506221116989

DiGiovanni, A. M.*, He, J.*, & Ochsner, K (in prep). Social emotion regulation: An inclusive framework and a guide to future research.

DiGiovanni, A. M., Vannucci, A., Ohannessian, C. M., & Bolger, N. (2021). Modeling heterogeneity in the simultaneous emotional costs and social benefits of co-rumination. Emotion, 21(7), 1470–1482. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001028

DiGirolamo, M. A., Neupert, S. D., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2023). Emotion regulation convoys: Individual and age differences in the hierarchical configuration of emotion regulation behaviors in everyday life. Affective Science, 4(4), 630–643.

Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Bernecker, S. L., & Christensen, K. (2015). Recent innovations in the field of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 36–42.

Dore, B. P., Morris, R. R., Burr, D. A., Picard, R. W., & Ochsner, K. N. (2017). Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one’s own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217695558

Doré, B. P., Silvers, J. A., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). Toward a personalized science of emotion regulation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(4), 171–187.

English, T., & Growney, C. M. (2021). A relational perspective on emotion regulation across adulthood. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 15(6), e12601.

Feeney, B. C., & Collins, N. L. (2015). A new look at social support: A theoretical perspective on thriving through relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(2), 113–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222

Fitzsimons, G. M., Finkel, E. J., & vanDellen, M. R. (2015). Transactive goal dynamics. Psychological Review, 122(4), 648–673.

Gable, S. L. (2006). Approach and avoidance social motives and goals. Journal of Personality, 74(1), 175–222.

Gable, S. L. (2008). Approach and avoidance motivation in close relationships. In Social relationships: Cognitive, affective, and motivational processes (pp. 219–234).

Girme, Y. U., Overall, N. C., & Simpson, J. A. (2013). When visibility matters: Short-term versus long-term costs and benefits of visible and invisible support. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(11), 1441–1454.

Gleason, M. E., Iida, M., Bolger, N., & Shrout, P. E. (2003). Daily supportive equity in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 1036–1045.

Gleason, M. E. J., Iida, M., Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2008). Receiving support as a mixed blessing: Evidence for dual effects of support on psychological outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(5), 824–838. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.824

Goldenberg, A., Halperin, E., van Zomeren, M., & Gross, J. J. (2016). The process model of group-based emotion: Integrating intergroup emotion and emotion regulation perspectives. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(2), 118–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315581263

Kalokerinos, E. K., Tamir, M., & Kuppens, P. (2017). Instrumental motives in negative emotion regulation in daily life: Frequency, consistency, and predictors. Emotion, 17(4), 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000269

Kruglanski, A. W., Chernikova, M., Babush, M., Dugas, M., & Schumpe, B. M. (2015). The architecture of goal systems: Multifinality, equifinality, and counterfinality in means—end relations. In Advances in motivation science (Vol. 2, pp. 69–98). Elsevier.

Liu, D. Y., Strube, M. J., & Thompson, R. J. (2021). Interpersonal emotion regulation: An experience sampling study. Affective Science, 2(3), 273–288.

McRae, K., Ciesielski, B., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Unpacking cognitive reappraisal: Goals, tactics, and outcomes. Emotion, 12(2), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026351

Miller, G. A., Galanter, E., & Pribram, K. H. (1960). The unit of analysis. In G. A. Miller, E. Galanter, & K. H. Pribram (Eds.), Plans and the structure of behavior (pp. 21–39). Henry Holt and Co. https://doi.org/10.1037/10039-002

Niven, K. (2016). Why do people engage in interpersonal emotion regulation at work? Organizational Psychology Review, 6(4), 305–323.

Niven, K. (2017). The four key characteristics of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 89–93.

Park, Y., Gordon, A., Humberg, S., Muise, A., & Impett, E. A. (2023). Differing levels of gratitude between romantic partners: Concurrent and longitudinal links with satisfaction and commitment in six dyadic datasets. Personality Science, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.5964/ps.10537

Peters, B. J., Overall, N. C., Gresham, A. M., Tudder, A., Chang, V. T., Reis, H. T., & Jamieson, J. P. (2024). Examining dyadic stress appraisal processes within romantic relationships from a challenge and threat perspective. Affective Science, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00235-3

Petrova, K., & Gross, J. J. (2023). The future of emotion regulation research: Broadening our field of view. Affective Science, 4(4), 609–616.

Reeck, C., Ames, D. R., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The social regulation of emotion: An integrative, cross-disciplinary model. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(1), 47–63.

Reis, H. T., Clark, M. S., & Holmes, J. G. (2004). Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness. In Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 211–236). Psychology Press.

Rossignac-Milon, M., Bolger, N., Zee, K. S., Boothby, E. J., & Higgins, E. T. (2021). Merged minds: Generalized shared reality in dyadic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 882–911. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000266

Sahi, R. S., He, Z., Silvers, J. A., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2023). One size does not fit all: Decomposing the implementation and differential benefits of social emotion regulation strategies. Emotion, 23(6), 1522–1535. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001194

Shu, J., Bolger, N., & Ochsner, K. N. (2021). Social emotion regulation strategies are differentially helpful for anxiety and sadness. Emotion, 21(6), 1144–1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000921

Simmons, J. M., Breeden, A., Ferrer, R. A., Gillman, A. S., Moore, H., Green, P., ... & Vicentic, A. (2023). Affective science research: Perspectives and priorities from the National Institutes of Health. Affective Science, 4(3), 600–607.

Springstein, T., & English, T. (2024). Distinguishing emotion regulation success in daily life from maladaptive regulation and dysregulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 28(2), 209–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/10888683231199140

Tamir, M. (2016). Why do people regulate their emotions? A taxonomy of motives in emotion regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(3), 199–222.

Tran, A., Greenaway, K. H., & Kalokerinos, E. K. (2024). Why do we engage in everyday interpersonal emotion regulation? Emotion. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001399

Tran, A., Greenaway, K. H., Kostopoulos, J., O’Brien, S. T., & Kalokerinos, E. K. (2023). Mapping interpersonal emotion regulation in everyday life. Affective Science, 4(4), 672–683.

Troy, A. S., Shallcross, A. J., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). A person-by-situation approach to emotion regulation: Cognitive reappraisal can either help or hurt, depending on the context. Psychological Science, 24(12), 2505–2514. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613496434

Uusberg, A., Ford, B., Uusberg, H., & Gross, J. J. (2023). Reappraising reappraisal: An expanded view. Cognition and Emotion, 37(3), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2023.2208340

Visserman, M. L., Righetti, F., Impett, E. A., Keltner, D., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2018). It’s the motive that counts: Perceived sacrifice motives and gratitude in romantic relationships. Emotion, 18(5), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000344

Zaki, J., & Williams, W. C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803–810.

Zee, K. S., & Bolger, N. (2019). Visible and invisible social support: How, why, and when. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(3), 314–320.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jo He for her important contributions to building out these ideas over the past few years.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

There is no funding to declare.

Competing Interests

There are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author Contribution

Ana DiGiovanni wrote the main manuscript text, and Kevin Ochsner edited the manuscript and contributed ideas.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Handling editor: Michelle Shiota

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

DiGiovanni, A.M., Ochsner, K.N. Emphasizing the Social in Social Emotion Regulation: A Call for Integration and Expansion. Affec Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00260-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-024-00260-2