Abstract

This work focused on the synthesis of 3D Pd-based nanocomposites which were tested in Heck coupling reactions and for the hydrogenation of nitroarenes. This was achieved by fabrication of graphene oxide/nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes (G/N-CNTs) by mechanical grinding of 2D graphene oxide (GO) and 1D oxygen-treated nitrogen-doped CNTs (N-CNTs-OT) in a 3:1 ratio, respectively. The fabrication of G/N-CNTs is to overcome the habitual aggregation and restacking of graphene sheets. Palladium nanoparticles (Pd NPs) were deposited on the 3D G/N-CNTs nanocomposites via metal organic chemical vapour deposition method. The 3D Pd-based nanocomposites were characterized by TEM, SEM, HRTEM, XRD, TGA, XPS, ICP-OES, elemental analysis, BET analysis and Raman spectroscopy. For the Heck coupling reactions, aryl halides, olefins and 3D Pd-based nanocomposites were mixed in a suitable solvent and the reaction carried under microwave irradiation. The chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroarenes was done with dry ethanol in a Paar reactor, purged with H2 gas. These catalysts demonstrate excellent activity and selectivity in both reactions. The remarkable activity of the 3D Pd-based nanocomposites in Heck reactions and hydrogenation of nitroarenes may be attributed to the small particle size (3–10 nm) and a high degree of dispersion of Pd NPs. A comparative experiment was conducted with Pd/AC, Pd/CNTs, Pd/G/CNTs and Pd/rGO. Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT showed higher activity and selectivity than Pd/G/CNTs, Pd/G/N-CNTs, Pd/rGO and Pd/N-CNTs counterpart.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Transition metal-catalysed protocols, especially those based on palladium (Pd), are of great interest in the field of catalysis [1]. This is because Pd-based catalysts are efficient and versatile for modern organic reactions. Pd-based catalysts offer a favourable combination of activity and selectivity as a result of the presence of closely packed Pd (111) facets [2]. Some of the well-known organic reactions in which Pd catalysts are used include carbon–carbon (C–C) bond forming reactions (i.e., Suzuki, Heck and Sonogashira coupling reactions) [3,4,5,6], oxidation of hydrocarbons [7, 8] and hydrogenation reactions [9].

Pd-catalysed Heck reactions, involving the reaction of aryl halides and olefins, are a potent synthetic methodology for the formation of C–C bonds [10, 11]. Pd-catalysed reactions have also found wide application in the pharmaceutical industry, especially for the reduction of nitroarenes into the corresponding amines [12]. Although various transition metals have been employed for nitroarene reduction, the Pd-catalysed reduction has been found to be highly selective and efficient for the production of primary amines [13]. For improved catalytic performance, various carbon supports for Pd nanoparticles (Pd NPs) such as two-dimensional (2D) graphene sheets [14] and one-dimensional (1D) functionalized [15] or doped carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [16] have been employed. However, limited functional groups and habitual restacking and aggregation of graphene and CNTs through π-π stacking and weak interfacial interaction with the Pd NPs have led to easy dissolution and poor dispersion of the Pd NPs on the supports [17,18,19].

To overcome this challenge, innovative three-dimensional (3D) nanocomposites involving the combination of graphene oxide and CNTs have been designed to minimize the restacking-induced surface area loss [13, 20, 21]. The resulting 3D graphene/CNT porous nanocomposites have a robust carbon architecture which contains a profuse number of oxygen-containing functional groups, that aid the adherence of Pd NPs onto the carbon structure. Several fabrication methods such as hydrothermal [22], sol–gel [23], chemical vapour deposition (CVD) [24], freeze drying [25], among others, have been employed for the synthesis of 3D graphene/CNT nanocomposites. The porous 3D graphene/CNT (G/CNTs) porous nanocomposites have been employed in various applications, such as electrocatalysis [26], solar cells [27] and water treatment [28]; and this is due to their improved surface area [29, 30], mechanical [24], electrical [31] and electrochemical properties [32]. The use of graphene/nitrogen-doped CNTs (G/N-CNTs) as a metal catalyst support in catalysis has not been fully exploited, despite the fact that this nanocomposite shows promising physicochemical properties [26]. Primarily, the catalytic properties of metal NPs depend on their particle size as well as the morphology of the support carbon nanomaterial support [33, 34].

Carbonaceous materials have found a wide application as Pd catalyst support. This is due to their excellent properties such as good electrical conductivity [35], stability [36], high surface area to volume ratios [37] and mainly their abundance and low cost [38]. CNTs have been widely employed as Pd catalyst support and this is due to their distinct structural and electronic properties [39]. However, their heteroatoms (such as nitrogen)-doped counterpart (N-CNTs) have been reported to display excellent support for Pd NPs in C–C reactions [40,41,42] and nitroarenes hydrogenation [43, 44] through enhanced Pd–N-CNTs interaction. This is because nitrogen atom can activate the adjacent carbon atoms due to its strong electron affinity to nitrogen, which enhances Pd metal adsorption [45]. The improved catalytic activity, coupled with N-CNTs morphology and basic properties attributed to pyrrolic-N or other types of nitrogen is directly related to the growth catalyst utilized, the type of C/N precursor used and the reaction conditions.

The common types of N bonding configurations in N-CNT are pyrrolic-N, quaternary-N and pyridinic-N [46]. Pyrrolic-N is the N atom in a five-membered ring configuration bonded to two carbon atoms, with two electrons donated to a π orbital to complete the aromatic ring [47]. Quaternary-N is the N atom directly substituted for a carbon atom in the hexagonal graphitic carbon network. The pyridinic-N type is a six-fold ring arrangement, with a lone pair, donated to a nonbonding orbital [48]. The pyrrolic-N are believed to be responsible for internal capping that creates the bamboo-like partitions in N-CNTs [49, 50]. Oxygen-containing molecule such as water [51], oxygen [52] CO2 [53] ethybenzoates [54] among others, have been introduced into the reactant mixture to (a) enhance the N-CNTs growth (b) morphology (c) fine-tune metal-support interactions [54, 55] and (d) functionalise the surface to improve N-CNTs hydrophobicity, adjust the pH and the electron-acceptor properties of N-CNTs [56].

In this study, G/CNTs G/N-CNTs and graphene/oxygen treated N-CNT (G/N-CNT-OT) nanocomposites with a 3D interconnected network were synthesized via mechanical grinding. A G/N-CNT-based nanocomposite was employed as a novel support to enhance the catalytic performance of Pd-catalysed reactions. The distinctive morphology and physicochemical properties of Pd/graphene/CNT (Pd/G/CNTs) and Pd/graphene/oxygen-treated N-CNT (Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT) was explored in Heck and nitroarene hydrogenation reactions. The catalytic efficiencies of these catalysts were elucidated, and various aspects were investigated including catalyst stability, selectivity and recyclability. To the best of our knowledge, Pd/G/N-CNT-OT nanocomposites have not been used as a catalyst for Heck and nitroarene hydrogenation reactions.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

All chemical reagents were purchased as analytical grade (98–99% purity) and used without additional purification. Graphite powder (> 99%), molecular sieves (3 Å beads, 8–12 mesh), magnesium turnings (98%), triethylamine (≥ 99%), potassium carbonate (≥ 99%), sodium hydroxide (≥ 97%), sodium carbonate anhydrous (≥ 99.9%), sodium bicarbonate (≥ 99.7%), hydrochloric acid (37%), tributylamine (99%), iodobenzene (98%), bromobenzene (≥ 99.5%), ethyl acrylate (≥ 99.5%), methyl acrylate (≥ 99%), triethylamine (≥ 99.5%) ammonia (≥ 99.5%), 4-nitrobenzoic acid (98%), 4-nitrophenol (≥ 99%), styrene (99.5%), dimethyl sulfoxide (99.9%), n-dodecane (≥ 99%) and ferrocene (98%) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Merck Chemicals supplied sulphuric acid (98%), potassium permanganate (99%), sodium nitrate (≥ 99%), sodium carbonate (≥ 99), dimethylformamide (≥ 99%), hydrogen peroxide (31%), ethanol (≥ 99%) (ethanol was further dried by stirring in magnesium metal turnings under reflux for few a hours, followed by distillation and subsequent drying with pre-activated molecular sieves), acetonitrile (≥ 99%), tetrahydrofuran (≥ 99%) and palladium(II) acetylacetonate (Pd(acac)2) (99%). Double-distilled ultrapure water was used for all solution preparation and washing.

2.2 Preparation of graphene oxide

Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared by oxidation of graphite powder using the modified Hummers method [57]. Briefly, graphite (2 g) and sodium nitrate (1 g) were added into concentrated H2SO4 (50 mL) contained in a 250 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer bar and placed in an ice bath. KMnO4 (6 g) was added slowly at intervals over approximately 30 min at a temperature of 5 °C. The solution was then stirred at 35 °C under reflux for 3 h, after which about 95 mL of double distilled water (DDW) was added. The solution was transferred into 270 mL of DDW in a beaker, followed by slow addition of 10 mL of H2O2 (30%) to quench excess KMnO4; this was confirmed by a colour change from black to yellow. The resulting suspension was filtered through a sintered glass funnel and washed with 10% HCl solution. Further washing was done until no sulphate was left in the filtrate. This was confirmed by the absence of a white precipitate after the addition of a few drops of barium chloride solution to the filtrate. The GO produced was washed with DDW until the pH of the washing was 6.8. The dark brown product obtained was dried in an oven at 40 °C for 24 h and then kept under ambient conditions.

2.3 Preparation of reduced GO

GO (50 mg) was ultrasonicated in DDW (25 mL) for 30 min. The brown mixture obtained was stirred for an hour to achieve a homogeneous dispersion. Ascorbic acid (50 mg) and conc. ammonia solution (0.5 mL) was added to the resulting dispersion until a pH of 9 was attained. The resulting solution was transferred into a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 170 °C for 5 h in order to reduce the GO. The reduced graphene oxide (rGO) obtained was washed severally with DDW and ethanol, filtered and then dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C for 10 h.

2.4 Preparation of CNTs and N-CNTs; and G/CNT and G/N-CNT composites

The synthesis and characterization of the 1,1′-ferrocenylmethyl[2-chloro imidazole] catalyst has been reported in our previous work [58]. Briefly, 1,1′-ferrocenedimethanol (240.9 mg, 1 mM) and 2-chloro-1H-imidazole (262.3 mg, 2.32 mM) were dissolved in acetic acid (3 mL) and refluxed at 60 °C for 7 h. On completion of the reaction, the product was neutralized with 7 mL of 50% KOH in water and treated with 20 mL of a 3:1 (v/v) mixture of diethyl ether and dichloromethane. The organic fraction of the product was separated and concentrated. The residue was purified by flash chromatography and recrystallized from CH2Cl2/diethyl ether.

CNTs were synthesized by using ferrocene (0.25 g) and toluene (9.75 g) as a catalyst and carbon source, respectively. N-CNTs were obtained by dissolving 1,1′-ferrocenylmethyl[2-chloro imidazole] (0.25 g) in acetonitrile (9.27 g). Oxygen treatment of N-CNTs (N-CNTs-OT) was achieved by dissolving 1,1′-ferrocenylmethyl[2-chloro imidazole] (0.25 g) and benzophenone (1 g) (oxygen source) in acetonitrile to make a 10 g solution of the reactant mixture. CNTs, N-CNTs and N-CNTs-OT were synthesized at 850 °C by means of the CVD technique.

The CVD procedure and set-up were used according to our previous report [59]. Briefly, the method involves the injection of the reactant mixtures through a syringe at a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1 into the quartz tube placed in a muffle furnace. The mixture was swept through the tube by 10% hydrogen in argon as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 100 mL min−1. After 30 min of reaction, the furnace was allowed to cool to 25 °C, and the product was scratched from the hot region of the quartz tube. The as-obtained products were calcined at 300 °C for 3 h to remove amorphous carbon and further treated with 6 M HNO3 under vigorous reflux at 80 °C for 24 h. The products were washed sequentially with water (4 × 20 mL) and ethanol (4 × 20 mL), and subsequently, oven-dried at 110 °C overnight.

The nanocomposites G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT were synthesized via mechanochemical grinding. In a typical experiment, GO (45 mg) was ground in CNTs (15 mg) (3:1) with a mortar and pestle and stored in a sealed container. In a similar fashion, and in the same quantity, N-CNTs or N-CNTs-OT were used instead of CNTs for the synthesis of other two nanocomposites.

2.5 Preparation of Pd/carbon supported nanocomposites

The metal organic CVD (MOCVD) technique, as outlined in a previous report [43], was used for the deposition of Pd onto the GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT carbon supports. About 0.048 g Pd(acac)2 was mixed with 0.316 g of carbon support, followed by thorough grinding using a pestle and mortar. The resulting mixture was transferred into a stainless steel MOCVD reactor and sealed. The sealed MOCVD reactor was evacuated with a vacuum pump maintained at a pressure of 2.1 × 10−2 mbar for 40 min. The MOCVD reactor was inserted into a CVD muffle furnace and maintained at 120 °C for 30 min. The temperature was subsequently increased up to 300 °C at a rate of 2 °C min−1 and afterward maintained at 300 °C for 45 min. The products obtained were labelled as Pd/GO, Pd/rGO, Pd/CNTs, Pd/N-CNTs, Pd/N-CNTs-OT, Pd/G/CNTs, Pd/G/N-CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT, respectively.

2.6 Characterization

The morphology of all samples was ascertained with a JOEL JEM 1010 scanning electron microscope (SEM). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was conducted on a JOEL JSM 6100 instrument. Samples for TEM analysis were prepared in alcohol and placed on a carbon-coated copper grid. The solvent was allowed to evaporate in air. Higher magnification images were obtained from a high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM). X-ray diffraction patterns were obtained with a Rigaku/Dmax RB powder X-ray diffractometer using graphite monochromatized high-density Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406). Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements were made by use of KBr pellets and the spectra recorded on a PerkinElmer Spectrum RX1 FTIR spectrometer. The thermal stabilities of the carbon nanomaterials were determined using a Q SeriesTM Thermal Analyzer TGA/DSC (Q600). Raman measurements were carried out on a DeltaNu Advantage 532™ Raman spectrometer. Nitrogen adsorption–desorption measurements and surface areas of all samples were determined with a Micrometrics Tristar II surface area analyser. The surface charge on carbon nanomaterials was determined with a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Nanosight NS500). The carbon nanomaterials were dispersed in 50 mL of double distilled water and the pH of the suspension was adjusted from 2 to 12 by adding either 0.1 M NaOH or 0.1 M HCl. The Pd content of the catalysts was determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) (PerkinElmer Optima 5300 DV). A CEM Discover SP microwave instrument was used for Heck reactions. All reactions were performed at 100–110 °C under a power output of 250 W. The products of the hydrogenation and Heck coupling reactions were analysed with a Shimadzu 2010 gas chromatograph coupled to a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and a Shimadzu gas chromatograph coupled to a mass spectrometer (GC–MS). The GC-FID and GC–MS experimental conditions are provided in the Supplementary Information. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was performed on a KRATOS AXIS Ultra DLD spectrometer equipped with Al Kα (1486 eV) X-rays, with an X-ray power of 20 W and a beam diameter of 100 μm. The CasaXPS program was employed for the analysis of the XPS data.

2.7 Catalytic testing

2.7.1 General procedure for Heck reaction

In a typical Heck reaction experiment, bromobenzene (5 mmol), ethyl acrylate (5.5 mmol), base (5.5 mmol) and the respective Pd catalyst (50 mg) were mixed in a suitable solvent (3 mL). (The mass of catalyst (50 mg) was determined after optimising the catalyst dosage over a range of 30–80 mg). The reaction mixture was then transferred into microwave tube equipped with a stirrer. Different solvents (DMF, THF, CH3CN and EtOH) and bases (Bu3N, Et3N Na2CO3, K2CO3 and EtONa) were employed for the optimization reactions. The reaction mixture was stirred and heated simultaneously at 110 °C for 15 min under microwave irradiation in a CEM Discovery apparatus. After the reaction, the products were cooled to room temperature and centrifuged to remove the catalyst. The products were separated by GC-FID on a 30 m DB-1 capillary column with n-dodecane as the internal standard. The column temperature was maintained at 100 °C for 10 min and then increased to 200 °C at 10 °C/min.

2.7.2 General procedure for reduction of nitroarenes

Nitroarene hydrogenation was carried out in a closed stainless-steel Parr reactor vessel equipped with pressure gauge and a temperature control. In this reaction, the Pd-based nanocomposite catalyst (150 mg) was added to the nitroarene (1041 mg) in dry ethanol (100 mL). (A mass of 150 mg of the catalyst was adopted after optimising different catalyst doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg). The reactor was sealed and purged with H2 and stirred continuously until the desired reaction condition was obtained. The reaction progress was monitored by collecting 1 mL aliquots of the reaction mixture at 2 h intervals. These samples were analysed off-line by GC-FID or GC–MS. On completion of the reaction, the catalysts were recovered by filtration through a 0.45 μm polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) syringe filter.

2.7.3 Recycling and leaching of the catalysts

Prior to recycling of the catalyst, it was washed with ethanol and diethyl ether and thereafter dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h. The model Heck reactions were performed with bromobenzene (5 mmol), ethyl acrylate (5.5 mmol), Et3N (5.5 mmol) and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT (50 mg) in DMF (5 mL) as the solvent under the optimized conditions. The reusability of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst was also tested on another substrate [i.e. iodobenzene (5 mmol) and styrene (5.5 mmol)] under similar optimized reaction conditions. The products were characterized off-line by GC-FID.

A hot filtration test was carried out to test if the Pd-based nanocomposite catalyst was leaching. Separation of catalyst was done in a model experiment for the Heck reaction (i.e. bromobenzene (5 mmol), ethyl acrylate (5.5 mmol), Et3N (5.5 mmol) and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT (50 mg) in DMF (5 mL) solvent). After 7.5 min of reaction at 110 °C, half of the reaction mixture was filtered off while hot to avoid possible precipitation of any leached Pd species on the catalyst surface. The Pd content in the filtered and remaining reaction mixture after 15 min was determined by ICP-OES.

3 Results and discussion

In this work GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst supports for Pd NPs were prepared and characterized. Pd NPs were then loaded onto these carbon supports by MOCVD. The resulting supported catalysts were evaluated in the Heck coupling reaction and for the hydrogenation of nitroarenes.

3.1 Material characterization

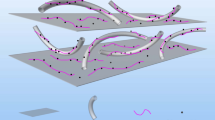

The morphology of CNTs or N-CNTs on GO (1:3) was ascertained by SEM analysis. Figure 1a–h shows the SEM micrographs of GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT, respectively. N-CNTs-OT is characterized by a vertically aligned morphology (Fig. 1e). The aligned morphology is due to the ‘cleaning’ effect of O2 which displaces excess H2 which could thwart the formation of sp2 carbon, and thus lead to the formation of water. G/CNT, G/N-CNT and G/N-CNT-OT nanohybrids yielded a self-organized, spongy and permeable morphology (Fig. 1f–h). The SEM micrographs of the G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs (Fig. 1f–g) reveals the intercalation of CNTs and N-CNTs into graphene layers. According to Wang et al. [60], the 3D interconnected network of the nanocomposites is probably as a result of weak van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding and π–π stacking. This interaction is assumed to occur during the mechanical grinding. The mechanochemical co-assembly of GO and N-CNTs is represented in Scheme 1.

The functionalities of the assemblies of CNTs or N-CNTs on GO were evaluated by using FTIR spectroscopy. The FTIR spectra of GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposites are shown in Fig. 2a, b. The FTIR spectrum of GO showed a broad O–H stretching vibration absorption band at 3461 cm−1. The absorption bands in GO observed at 1715, 1585, 1346, 1220 and 1032 cm−1 are ascribed to C=O stretching, sp2 C=C or C=N, O–H stretching in C–OH group, C–N functional group and C–O stretching in epoxides, respectively. The observed decrease in the intensity of C–O (1032 cm−1) and C=O (1715 cm−1) bands in G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs-OT (Fig. 2b) may be due to the reduction and dehydration reactions of carbonyl and hydroxyl groups of GO and N-CNTs, respectively. The mechanochemical reaction between GO and CNTs or N-CNTs resulted in the elimination of the 1346, 1585 and 1715 cm−1 absorption peaks of GO, hence, they were not observed in G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNT-OT. This is indicative of a chemical reaction between the two carbon materials. The band at 3420 cm−1 disappears in the FTIR spectrum of rGO, and this is due to the reduction of C=O and O–H functional groups.

The spectral pattern of CNTs and N-CNTs-OT showed absorption bands between 1000 and 2100 cm−1 (Fig. 2b). This suggests that hydroxyl, epoxy, and carboxyl functional groups were present on the surface of the carbon materials. A broad absorption peak at 2400 cm−1 was observed for both G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs [61]. This band broadening is attributed to intermolecular (O–H…O=C) hydrogen bonding between the OH stretching mode in GO and the oxygen functionality (i.e. hydroxyl, epoxy and carboxyl groups) on oxidized CNTs, N-CNTs and N-CNTs-OT, which act as H-bond acceptors [61]. G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT show similar C=O stretching modes (1715 cm−1) and alkoxy C–O (1150 cm−1) stretches, demonstrating a controlled vibration activity related to GO [61]. Additionally, the band at 671 cm−1 (Fig. 2c) corresponds to the O–Pd–O bond [62], indicating the interaction of Pd(II) with the oxygen functionalities on the GO, CNTs, N-CNTs, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs or G/N-CNTs-OT surfaces during the mechanical grinding.

Zeta potential analysis was employed to measure the surface properties of the nanocomposite carbon supports. The surface charge of the carbon supports could influence the electronic characteristics of the active phase. Figure 3a, b shows the zeta potential studies of GO, CNTs, N/CNTs, and the G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposites as a function of pH. The grafting of N-CNTs as ‘spacers’ to prevent GO restacking in G/N-CNTs-OT led to the formation of basic sites on the support. The presence of a large number of cross-linked aromatic rings in GO provides a high possibility of close parallel packing with N-CNTs by strong π–π interactions. When GO was added to N-CNTs-OT, the anionic groups on GO (negatively charged) interact with the electro-conductive surface of N-CNTs-OT (positively charged at pH below 6), thereby making the nanocomposite electrostatically repulsive.

This interpretation was supported experimentally as the zeta potential of GO, CNTs, N-CNTs-OT were below − 30 mV at pH greater than 6.8 and increased up to zeta potential above − 52 mV for G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT at pH 10 (Fig. 3b). This shows that nanocomposites are negatively charged, indicative of mutual repulsion and stable colloidal dispersion [63, 64]. The point of zero charge (pzc) of GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs and N-CNTs-OT were at pH 2, 5, 3, 6.7 and 7, respectively. However, the pzc of G/N-CNTs-OT was 7.3, much higher than GO,CNTs and N-CNTs. This increase in pzc value for G/N-CNTs-OT could be attributed to the presence of nitrogen-containing functionality in N-CNT spacer employed to prevent GO restacking [60] The zeta potential obtained is consistent with that reported in the literature [65].

The results of the TGA analysis of all samples conducted in a N2 atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min are shown in Fig. 4. Substantial weight losses occurred in GO, rGO, CNTs, G/CNTs, N-CNTs-OT and G/N-CNTs-OT at temperatures of 375, 355, 783, 794, 710 and 695 °C, respectively. This indicates that GO and rGO are less stable than the other carbon supports. The weight loss (9%) observed for GO at temperatures below 100 °C could be due to the elimination of water or hydroxyl groups present in the π-stacked structure [66], and this correlates with the assigned FTIR absorption peak at ~ 3461 cm−1 (Fig. 4). The significant weight loss observed in GO at a temperature around 150 °C corresponds to the displacement of oxygen-containing functional groups [66].

The thermal stability of G/N-CNTs-OT is higher than that of pure N-CNTs-OT. This may be due to the strong interaction of N-CNTs-OT and GO. Weight losses were observed for G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT at 235 and 339 °C, respectively, probably as a result of GO decomposition, while peaks at 410 and 430 °C were attributed to CNTs and N-CNT decomposition temperatures, respectively (Figure S1). After deducting the adsorbed water, the residual carbon content of GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposites were 63, 71, 94, 56, 72 and 60%, respectively, at 1000 °C.

The TGA weight loss under a N2 atmosphere at temperatures between 25 and 1000 °C reveals the percentage oxygen functionalization on the nanocomposites. The decomposition temperatures of the carbon supports that ranged from 150 to 400, 401 to 500 and 650 to 700 °C and were ascribed to –COOH, –COO– and –OH functional groups, respectively [67,68,69]. G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT possess more stable oxygen functionalities, as only a one-step weight loss was observed between 100 and 900 °C (Fig. 4 and Table S1). The percentage of the surface oxygen-containing groups obtained from the TGA results increase in the order GO > G/N-CNTs > G/N-CNTs-OT > rGO > CNTs.

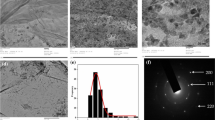

The Pd NPs size and distribution on the various carbon supports was investigated by TEM analysis. The TEM micrographs of the Pd/G/CNTs-OT and Pd/rGO composites (Fig. 5a, b) show a uniform distribution of Pd NPs. For all Pd-based catalysts, different particle size distribution with average Pd NPs sizes ranging from 3 to 10 nm (Table 1) were obtained. The HRTEM images of Pd/N-CNTs-OT revealed the microstructure of the Pd NPs (Fig. 5c and Figure S2). The HRTEM images of all the Pd-based nanocomposite catalysts (Figure S2) display typical fcc Pd pattern with lattice fringes of ~ 0.195 and 0.222 nm indexed to the (200) and (111) planes, respectively. The selective area electron diffraction pattern (SAED) of Pd/N-CNTs-OT (Fig. 5d) also shows bright concentric rings composed of discrete diffraction spots indexed to the (111), (200) and (220) planes of the fcc Pd metal. This is indicative of the deposition of highly crystalline Pd NPs. The GO, CNTs, G/CNTs and G/N-CNTs powder were further characterized by Raman spectroscopy and powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis.

The structural parameters of the synthesized nanocomposites were examined by means of Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 6). The Raman spectra of GO, rGO, CNTs and N-CNTs showed well-denoted D- and G-bands. The D-band (1354 cm−1) is ascribed to sp3 defects, while the G-band (1598 cm−1) is due to in-plane vibrations of sp2 carbon atoms and the E2g symmetry at the Brillouin zone centre [70]. Successful reduction of GO to rGO was confirmed by the downshift of the G-band from 1590 cm−1 (GO) to 1581 cm−1 (rGO) and this is due to the restoration of the π-conjugated structure during thermal treatment [71]. The G-bands of G/CNT and G/N-CNTs nanocomposites appeared at a higher wavenumber indicative of increased numbers of graphene layers [72]. The ID/IG ratio relating to structural defects in the GO, rGO, CNTs, N-CNTs, N-CNTs-OT, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposites was calculated. ID/IG values for the samples follow the order rGO < GO < CNT < N-CNT < G/CNT < G/N-CNT-OT (Table 1). The incorporation of N atoms into the graphitic carbon network usually lead to defects in the sp2 graphitic carbon [73]. The ID/IG value of GO is 0.55, whereas the ID/IG ratios for G/N-CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT are 0.84, 1.39 and 1.22, respectively. This further indicates the reduction of GO and effective doping of N atoms into CNTs since in both cases the number of defects in the carbon structure are increased. The shift in the G-band peak from 1597 cm−1 in GO to 1592 cm−1 G/N-CNTs is due to the interaction between GO and N-CNTs [74, 75].

Figure 7 shows the powder X-ray diffraction patterns of GO, Pd/rGO, Pd/CNTs, Pd/N-CNTs, Pd/N-CNTs-OT, Pd/G/CNTs, Pd/G/N-CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT. The diffraction peak (002) at 2θ = 11° (d-spacing 0.86 nm) is ascribed to the oxidation of graphene to GO, indicative of exfoliation of graphite sheets. For rGO, the diffraction peak at 2θ = 25.7° (d-spacing 0.32 nm) indexed to the 002 plane of graphene is indicative of the reduction or partial removal of the surface oxygen-containing groups on GO surfaces [76]. Pd/G/N-CNTs and Pd/N-CNTs showed a broad diffraction peak appearing at 2θ = 26.35° (d-spacing 0.35 nm), indexed as the 002 planes of graphene and N-CNTs [77]. For Pd/G/CNTs, the disappearance of the characteristic peak of GO (2θ = 11°) and the appearance of the sharp peak at 2θ = 22.0° is ascribed to turbostratic graphite. This also indicates that GO can be reduced during the Pd(acac)2 reduction process [78]. The diffraction peak at 2θ = 26.35° for N-CNTs is weaker and broader than that of CNTs and this is due to less re-graphitization resulting from the incorporation of N atoms into the graphitic carbon skeleton. Similar diffractograms were observed for N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs which indicates a homogeneous distribution of N-CNTs on the graphene surface, with little or no graphene sheet stacking.

The diffraction peaks observed around 2θ = 39° and 2θ = 44° were indexed to the (111) and (200) lattice planes, respectively, and ascribed to metallic Pd. The average Pd NP size estimated via the Scherrer equation correlates with the values obtained from TEM analysis (Table 1). The concentration Pd on GO, CNTs, N-CNTs, G/CNTs, G/N-CNTs and G/N-CNTs-OT was estimated to be approximately 0.02 mol% for all samples from ICP-OES measurements (Table 2).

The N2 sorption analysis of supported Pd-based nanocomposites is shown in Fig. 8. All Pd composites demonstrate a typical IUPAC type IV isotherm indicating a narrow size distribution of mesopores [79] with a reduced pore-blocking effect during desorption [80]. This is attributed to the insertion of CNTs or N-CNTs into the graphene sheet layers. The pore volume ranges from 0.373 to 0.664 cm3 g−1 in all materials (Fig. 8c). The accessible surface area of Pd-based nanocomposites ranges from 71.65 to 252.10 m2 g−1 (Table 3), with Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT exhibiting a higher specific surface area (252.70 m2 g−1) than Pd/rGO (125.85 m2 g−1).

The BET surface area for GO is lower than the reported values [81,82,83], attributed to graphene agglomeration (strong π-stacking between different graphene sheets). The surface areas of the Pd/G/CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs nanocomposites are higher due to the bridging of adjacent graphene sheets during CNT or N-CNT insertion into GO, thereby preventing graphene sheet restacking [84, 85]. CNT and N-CNT intercalation within the graphene layers tends to create more space between the graphene sheets, leading to the production of mesopores and a larger specific surface area.

The elemental composition and the effects of CNT or N-CNT incorporation on the microstructure of GO and the properties of the Pd nanocomposites was investigated by XPS analysis. The results are presented in Fig. 9. As shown in Fig. 9a, the full scan spectra of Pd/GO, Pd/G/CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT showed the characteristic peaks of all expected elements namely: C 1s (284.3 eV), N 1s (399.7 eV), O 1s (531.2 eV) and Pd 3d (335.4 eV). The C/O atomic ratio improved slightly from 3.68 in GO to 4.39 in G/CNTs, which is indicative of the partial reduction of the surface oxygen-containing groups. This C/O ratio increases upon incorporation of N-CNTs-OT into GO (Table 3). Deconvolution of the C 1s peaks (Fig. 9b and Table 3) show characteristic peaks at 284.5 eV (C–C), 286.4 eV (C=O) and 400.8 eV (C=N) for Pd/GO, Pd/G/CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT, respectively. The C 1s peak of GO is the most intense (42.53%) at the highest binding energy (286.0 eV). This is due to the abundance of oxygen-containing functional groups (Fig. 9b). The percentage of the C=O bond decreases for Pd/G/CNTs (20.31%) and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT (15.16%), leading to an increase in the percentage of the C–O bond from 12.38 to 21.78% (Table 4).

The oxidation state of Pd in Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT was investigated. The characteristic peaks at 335.4 and 341.2 eV of the Pd 3d core level region could be assigned to Pd 3d5/2 and Pd 3d3/2, respectively (Fig. 9c) [86]. This result confirms the presence of metallic Pd in the 3D framework of porous G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposites. The O 1s spectrum (Figure S3) showed the contribution of two species of oxygen ascribed as O1 (C=O, 531.5 eV) and O2 (C–O, 533.6 eV) for Pd/GO, Pd/G/CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs. The N 1s peaks for Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT exhibit two prominent peaks for different N species (Fig. 9d). The peaks at 398.57 eV (pyridinic-N), 400.20 eV (pyrrolic-N) and 400.81 eV (quaternary-N) are present in 17.87, 82.09 and 0.04 at.%, respectively for Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT (Fig. 9d).

In summary, we have been able to synthesise different carbon material as support for Pd NPs. The carbon materials supported Pd catalysts were evaluated in Pd catalysed reactions such as Heck coupling and nitroarene hydrogenation.

3.2 Heck reactions

The catalytic activity of all synthesized catalysts was evaluated in the Heck reaction by using iodobenzene and ethyl acrylate as the model substrates. The reaction conditions were optimized by using the Pd/N-CNTs catalyst with different bases (Bu3N, Et3N Na2CO3, K2CO3 and EtONa), as well as a series of solvents (DMF, THF, CH3CN and EtOH) at 110 °C for 15 min. Amongst the screened bases, Et3N proved to be the best base (Table 5, entry 1). Moderate yields were obtained for Bu3N and Na2CO3 (Table 5, entries 5 and 9), while K2CO3 and EtONa afforded lower yields (Table 5, entries 7 and 11). DMF was found to be the most suitable solvent for the chosen catalyst (Table 5, entry 1) compared with the other solvents such as THF, EtOH, CH3CN and DMSO (Table 5, entries 3–5 and 7–12).

The efficiencies of the synthesized catalysts were tested in the Heck coupling reaction under the optimized reaction conditions (Fig. 10) and compared with that of a commercial Pd catalyst, namely Pd/activated carbon (Pd/AC). The coupling products were obtained at 98, 97 and 99% conversions for Pd/rGO, Pd/N-CNTs-OT and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT, respectively, after 15 min of reaction (Fig. 10). The activities of Pd/AC (68%), Pd/CNTs (69%) and Pd/N-CNTs (78%) were slightly lower than for the other catalysts. The lower catalytic activity of Pd/CNTs and Pd/N-CNTs, compared with Pd/rGO, Pd/N-CNTs-OT and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT could be due to the relatively larger Pd particle size.

The catalytic activities of the Pd-based nanocomposites were tested by employing Pd/rGO, Pd/G/N-CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT as catalysts for the Heck coupling reaction of a substituted aryl halide (i.e. with either electron-withdrawing or electron-donating groups) and olefins. The three catalysts gave excellent conversions for styrene, methyl acrylate and ethyl acrylate (Table 6, entries 1–6). The conversion decreased when iodobenzene was replaced with bromobenzene (Table 6, entries 4 and 6).

The reaction of styrene and aryl iodides with electron-withdrawing groups (such as –NO2 and –COCH3) (Table 6, entries 7 and 8) and electron-donating groups (such as –OH, –NH2 and –CH3) (Table 6, entries 9–11) gave higher conversion for Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT than for Pd/rGO and Pd/G/N-CNTs. This could be attributed to the effect of the oxygen treatment in N-CNTs-OT that led to an increase in C–O functional groups and also the presence of mainly pyrrolic-N atoms in the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst. The high number of defects induced by nitrogen incorporation and oxygen treatment of N-CNTs, and the synergistic effect of GO nanosheets, lowers the work function of the nanocomposites. Pd/rGO, Pd/G/N-CNTs and Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT gave turnover frequency (TOF) values of 963, 782 and 1056 h−1, respectively, for the reaction of styrene and iodobenzene. The results obtained in this study were consistent with those previously reported for graphene-based Pd catalysts in microwave-assisted Heck coupling reactions (Table 7). The Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst gave better conversions than Pd catalysts with silica, zeolites or rGO as supports (Table 7).

3.3 Hydrogenation reactions of nitroarenes

The catalytic activity and selectivity of 3D Pd nanohybrid catalysts were evaluated in the reduction of nitroarenes with nitrobenzoic acid (NBA) as the model substrate in dry ethanol at room temperature and 50 °C (Table 8). Low conversion was obtained at both temperatures for a control reaction conducted without catalyst (Table 8, entry 1). This suggests that the reaction cannot proceed without a Pd catalyst. Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT and Pd/rGO catalysts showed a higher conversion (97–99%) with 1 MPa H2 at room temperature than at 50 °C (Table 8, entries 2 and 4). On the other hand, the catalyst Pd/AC showed 84% and 89% conversion when the reaction was carried out at room temperature and at 50 °C, respectively (Table 8, entry 7).

Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT showed a greater conversion of NBA than Pd/rGO, Pd/CNTs and Pd/G/CNTs at room temperature (Table 8). This could be as a result of the higher H2 adsorption capacity of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT since this materials had the highest surface area [96]. Since G/N-CNTs-OT showed a moderate conversion (Table 8, entry 8), it is plausible that the presence of pyrrolic-nitrogen in Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT, as observed from XPS analysis, enhances the catalytic activity [42]. The higher catalytic activity could also be attributed to the increased number of C–O functional groups in the G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposite and the higher surface area of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst [42]. It is also plausible that N-CNTs-OT is a better ‘spacer’ of graphene layers for hydrogenation of NBA than CNTs.

In all Pd-based nanocomposites, the selectivity towards 4-aminobenzoic acid (ABA) increases from 40 to 97% after 10 h at room temperature, compared to an increase from 10 to 46% for reactions at 50 °C, during the first 6 h (Figure S4 and Figure S5). However, the selectivity towards ABA was lower at the 50 °C reaction temperature, and this is due to the possible formation of the 4-nitrosobenzoic acid intermediate. GC–MS characterization showed 4,4′-hydrazodibenzoic acid (HBA) as a by-product. The type of carbon support appears to have an influence on catalyst selectivity. For instance, the G/N-CNTs-OT nanocomposite was of superior selectivity compared with CNTs, N-CNTs and activated carbon (AC) (Table 8, entry 4). Additionally, the use of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT with 0.02 mol. % Pd loading provides an alternative heterogeneous catalyst for the chemoselective reduction of nitro groups under mild conditions compared with commercial Pd/AC (Table 8).

After optimization of the reaction conditions, chemoselective hydrogenation of other nitroarenes was carried out over the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst in dry ethanol at room temperature. High conversions (i.e. > 90%) of the nitro compounds with high selectivity towards the corresponding amine was recorded in all cases. The hydrogenation of 4-nitroacetophenone, 4-nitrophenol and 4-nitrobenzoic acid gave corresponding amino products (Table 9). Also, higher selectivity towards chloroaniline was obtained for the hydrogenation reaction of chloronitrobenzene without the dehalogenation of chloronitrobenzene, and this is typical of heterogeneous catalysts [97].

4-Nitrobenzene, 4-nitrobenzoic acid and 1-ferrocenylmethyl(2-nitroimidazole) produce 99% conversions of the substrates to their corresponding products at room temperature within 6 h (Table 9, entries 1, 7 and 8). 4-Nitrophenol, 1-chloronitrobenzene and 4-nitrobenzaldehyde were not completely converted. 4-Nitrotoluene with an electron-donating group exhibits a lower catalytic activity within 6 h (Table 9, entry 2). However, nitroarenes with electron-withdrawing groups, such as 4-nitroacetophenone, 4-nitrobenzaldehyde, 1-chlorobenzoic acid and 4-nitrobenzoic acid, were easily reduced into the corresponding products with > 90% conversion (Table 9, entries 3–7). The Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst with 0.02 mol% Pd loading afforded better conversion of nitroarenes to their corresponding products with TOF values up to 2352 h−1 at room temperature. Based on the observations recorded for the reaction above, a plausible reaction mechanism was proposed (Scheme 2). A comparison of the study findings with those of previously reported Pd-based nanocomposites for hydrogenation reactions indicates that our synthesized Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst had a very high TOF value (Table 10).

3.4 Kinetics of Pd-based nanocomposites

The kinetics of the catalytic activities of the Pd-based nanocomposites in the Heck reaction were evaluated. The conversion (C) of the reactant as a function of time (t) for the Heck reaction was obtained. For all the Pd-based nanocomposites the reaction followed pseudo-first-order kinetics (R2 > 0.98) with respect to iodobenzene as depicted in the linear plots shown in Fig. 11 [110]. The pseudo-first-order rate constants (k) for the Heck reaction at 110 °C are listed in Table S2. The rate constants for the Heck reaction increase in the order: Pd/N-CNTs-OT > Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT > Pd/rGO > Pd/G/N-CNTs > Pd/G/CNTs > Pd/N-CNTs > Pd/AC > Pd/CNTs.

The dependence of the catalytic activities of Pd-based nanocomposites on the catalyst surface area was investigated by evaluating the rate constants for the hydrogenation of NBA (Table S3). The plots of − ln(1 − C) as a function of t were found to be linear and followed pseudo-first-order kinetics (R2 > 0.98) (Fig. 12). The k values for the hydrogenation of NBA follow the order: Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT > Pd/rGO > Pd/N-CNTs > Pd/CNTs. The catalytic activity of all investigated Pd-based nanocomposites is dependent on the physicochemical properties such as surface area of the support and suitable Pd-support interaction. The high activity and selectivity of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst is due to the ease of diffusion of hydrogen gas into the larger pores of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT particles leading to easy mass transfer from the bulk gas phase to the bulk liquid phase. The hydrogenation activity indicates that Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT (i.e. k = 0.3057 h−1) has more catalytically active sites due to the larger surface area, than catalysts with lower surface areas. Hence, the rate of hydrogenation of NBA is dependent on the surface area of the Pd catalyst support.

3.5 Leaching test

The heterogeneity test on all Pd-based nanocomposite catalysts was carried out for the Heck reaction of styrene and iodobenzene, in order to examine the provisional release of active species from the catalysts. The catalysts were filtered off from the reaction mixture after 7 min reaction time. The filtrate was retained in the microwave tube under stirring at 110 °C for further reaction. After determining the extent of conversion by GC-FID method, no observable change in the conversion of NBA was detected after 15 min (Figure S6). In addition, it was observed that Pd was not leached out of the mesoporous support during the catalytic reaction, as no Pd was detected from the ICP-OES analysis of the filtrate. The hot filtration test, therefore, revealed strong bonding between the Pd NPs and the synthesised robust mesoporous carbon supports.

3.6 Catalyst recyclability

Catalyst recyclability is a critical concern in heterogeneous catalysis. The recyclability of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst was investigated in the Heck coupling reaction of iodobenzene and styrene (Fig. 13, Table S4). The use of this catalyst resulted in 95% conversion within 18 h after ten successive runs without significant loss of activity. The catalyst was separated from the reaction mixture by washing with ethanol (3 times), oven-dried at 50 °C overnight and used in the next catalytic run.

The stability of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT was also investigated in the hydrogenation of nitroarenes. Higher catalytic activity was obtained for the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst with 98% conversion after six consecutive cycles (Table S5). This result further confirms the stability and recyclability of the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst.

4 Conclusions

In summary, we have synthesized Pd NPs supported on recyclable carbon nanocomposites (such as GO, CNTs, N-CNTs and N-CNTs-OT) for microwave-assisted Heck coupling reactions and hydrogenation of nitroarenes. The nanohybrid interaction is driven by π-π interactions and the hydrophobic interface between GO and CNTs or N-CNTs obtained via mechanical grinding, leading to a mesoporous architecture and continuous sp2 hybridized networks. Our work provides an alternative green approach for building a 3D nanohybrid G/N-CNT matrix. It has been established that the encapsulation of N-CNTs by GO and the predominant pyrrolic-N atom doping in the Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst play a vital role in excellent catalytic activities. Oxygen treatment with benzophenone during N-CNT synthesis was found to show a varied effect on the catalytic performance with an enhanced C–O oxygen-containing functional group as observed from XPS analysis. The Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst exhibited outstanding activity in nitroarene hydrogenation and microwave-assisted Heck coupling activity, which could be ascribed to the heterogeneity of the carbon supports. The conversion of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT towards nitroarene compounds with a reducible functional group was > 99% compared with other reported Pd catalysts. Higher coupling activity of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT catalyst in microwave-assisted Heck reaction was due to the stable interface between Pd NPs and the carbon support, thereby averting leaching of Pd NPs from the carbon support. The observed high catalytic activity of Pd/G/N-CNTs-OT in creating a new C–C bond via Heck coupling and reduction of nitroarenes into the corresponding amines is potentially important for applications in organic synthesis.

References

Feng Z, Min Q-Q, Fu X-P, An L, Zhang X (2017) Chlorodifluoromethane-triggered formation of difluoromethylated arenes catalysed by palladium. Nat Chem 9:918

Tereniak SJ, Stahl SS (2017) Mechanistic basis for efficient, site-selective, aerobic catalytic turnover in Pd-catalyzed C–H imidoylation of heterocycle-containing molecules. J Am Chem Soc 139:14533–14541

Khalafi-Nezhad A, Panahi F (2012) Immobilized palladium nanoparticles on silica–starch substrate (PNP–SSS): as a stable and efficient heterogeneous catalyst for synthesis of p-teraryls using Suzuki reaction. J Organomet Chem 717:141–146

Veisi H, Khazaei A, Safaei M, Kordestani D (2014) Synthesis of biguanide-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) hybrid materials to immobilized palladium as new recyclable heterogeneous nanocatalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction. J Mol Catal A Chem 382:106–113

Zhang H, Zhou M, Xiong L, He Z, Wang T, Xu Y et al (2017) Amine-functionalized microporous organic nanotube frameworks supported Pt and Pd catalysts for selective oxidation of alcohol and Heck reactions. J Phys Chem C 121:12771–12779

Adib M, Karimi-Nami R, Veisi H (2016) Palladium NPs supported on novel imino-pyridine-functionalized MWCNTs: efficient and highly reusable catalysts for the Suzuki–Miyaura and Sonogashira coupling reactions. New J Chem 40:4945–4951

Yang H, Yu Z, Li S, Zhang Q, Jin J, Ma J (2017) Ultrafine palladium-gold-phosphorus ternary alloyed nanoparticles anchored on ionic liquids-noncovalently functionalized carbon nanotubes with excellent electrocatalytic property for ethanol oxidation reaction in alkaline media. J Catal 353:256–264

Lin X, Nie Z, Zhang L, Mei S, Chen Y, Zhang B et al (2017) Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes encapsulate cobalt nanoparticles as efficient catalysts for aerobic and solvent-free selective oxidation of hydrocarbons. Green Chem 19:2164–2173

Zhang L, Wang B, Ding Y, Wen G, Hamid SBA, Su D (2016) Disintegrative activation of Pd nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes for catalytic phenol hydrogenation. Catal Sci Technol 6:1003–1006

Corma A, Garcia H, Leyva A (2005) Catalytic activity of palladium supported on single wall carbon nanotubes compared to palladium supported on activated carbon: study of the Heck and Suzuki couplings, aerobic alcohol oxidation and selective hydrogenation. J Mol Catal A Chem 230:97–105

Cano M, Benito A, Maser WK, Urriolabeitia EP (2011) One-step microwave synthesis of palladium–carbon nanotube hybrids with improved catalytic performance. Carbon 49:652–658

Bai H-Y, Ma Z-G, Yi M, Lin J-B, Zhang S-Y (2017) Palladium-catalyzed direct intermolecular amination of unactivated methylene C(sp 3)–H bonds with azodiformates via bidentate-chelation assistance. ACS Catal 7:2042–2046

Yang F, Feng A, Wang C, Dong S, Chi C, Jia X et al (2016) Graphene oxide/carbon nanotubes–Fe3O4 supported Pd nanoparticles for hydrogenation of nitroarenes and C–H activation. RSC Adv 6:16911–16916

Khan M, Kuniyil M, Shaik MR, Khan M, Adil SF, Al-Warthan A et al (2017) Plant extract mediated eco-friendly synthesis of Pd@graphene nanocatalyst: an efficient and reusable catalyst for the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling. Catalysts 7:20

Dong W, Xia W, Xie K, Peng B, Muhler M (2017) Synergistic effect of potassium hydroxide and steam co-treatment on the functionalization of carbon nanotubes applied as basic support in the Pd-catalyzed liquid-phase oxidation of ethanol. Carbon 121:452–462

L-l Wang, L-p Zhu, N-c Bing, L-j Wang (2017) Facile green synthesis of Pd/N-doped carbon nanotubes catalysts and their application in Heck reaction and oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J Phys Chem Solids 107:125–130

Gu X, Qi W, Xu X, Sun Z, Zhang L, Liu W et al (2014) Covalently functionalized carbon nanotube supported Pd nanoparticles for catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol. Nanoscale 6:6609–6616

Bai S, Shen X (2012) Graphene–inorganic nanocomposites. RSC Adv 2:64–98

Thathagar MB, ten Elshof JE, Rothenberg G (2006) Pd nanoclusters in C–C coupling reactions: proof of leaching. Angew Chem Int Ed 45:2886–2890

Ni Y, Chen L, Teng K, Shi J, Qian X, Xu Z et al (2015) Superior mechanical properties of epoxy composites reinforced by 3D interconnected graphene skeleton. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 7:11583–11591

Bae S-H, Karthikeyan K, Lee Y-S, Oh I-K (2013) Microwave self-assembly of 3D graphene-carbon nanotube-nickel nanostructure for high capacity anode material in lithium ion battery. Carbon 64:527–536

Chen M, Liu J, Chao D, Wang J, Yin J, Lin J et al (2014) Porous α-Fe2O3 nanorods supported on carbon nanotubes-graphene foam as superior anode for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 9:364–372

Sun H, Xu Z, Gao C (2013) Multifunctional, ultra-flyweight, synergistically assembled carbon aerogels. Adv Mater 25:2554–2560

Yang Y, Kim ND, Varshney V, Sihn S, Li Y, Roy AK et al (2017) In situ mechanical investigation of carbon nanotube-graphene junction in three-dimensional carbon nanostructures. Nanoscale 9:2916–2924

Kong L, Yin X, Yuan X, Zhang Y, Liu X, Cheng L et al (2014) Electromagnetic wave absorption properties of graphene modified with carbon nanotube/poly (dimethyl siloxane) composites. Carbon 73:185–193

Lv Q, Si W, Yang Z, Wang N, Tu Z, Yi Y et al (2017) Nitrogen-doped porous graphdiyne: a highly efficient metal-free electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9:29744–29752

Zhu G, Pan L, Lu T, Xu T, Sun Z (2011) Electrophoretic deposition of reduced graphene-carbon nanotubes composite films as counter electrodes of dye-sensitized solar cells. J Mater Chem 21:14869–14875

Fei J, Cui Y, Zhao J, Gao L, Yang Y, Li J (2011) Large-scale preparation of 3D self-assembled iron hydroxide and oxide hierarchical nanostructures and their applications for water treatment. J Mater Chem 21:11742–11746

Trogadas P, Fuller TF, Strasser P (2014) Carbon as catalyst and support for electrochemical energy conversion. Carbon 75:5–42

Zhu S, Wang J, Fan W (2015) Graphene-based catalysis for biomass conversion. Catal Sci Technol 5:3845–3858

Zhang Q, Wang Y, Zhang B, Zhao K, He P, Huang B (2018) 3D superelastic graphene aerogel-nanosheet hybrid hierarchical nanostructures as high-performance supercapacitor electrodes. Carbon 127:449–458

Huang B, Liu J, Lai L, Yu F, Ying X, Ye B-C et al (2017) A free-standing electrochemical sensor based on graphene foam-carbon nanotube composite coupled with gold nanoparticles and its sensing application for electrochemical determination of dopamine and uric acid. J Electroanal Chem 801:129–134

H-q Song, Zhu Q, X-j Zheng, X-g Chen (2015) One-step synthesis of three-dimensional graphene/multiwalled carbon nanotubes/Pd composite hydrogels: an efficient recyclable catalyst for Suzuki coupling reactions. J Mater Chem A 3:10368–10377

Ali M, Abarca G, Eberhardt D, Gual A, Bernardi F, Teixeira SR et al (2017) “Save money” during hydrogenation reactions by exploiting the superior performance of Pd-NPs deposited on carbon black by magnetron sputtering. Tetrahedron 73:5593–5598

Wei D, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Huang L, Yu G (2009) Synthesis of N-doped graphene by chemical vapour deposition and its electrical properties. Nano Lett 9:1752–1758

Liu H, Zhang Y, Li R, Sun X, Désilets S, Abou-Rachid H et al (2010) Structural and morphological control of aligned nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes. Carbon 48:1498–1507

Rao CV, Cabrera CR, Ishikawa Y (2010) In search of the active site in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube electrodes for the oxygen reduction reaction. J Phys Chem Lett 1:2622–2627

Shao Y, Sui J, Yin G, Gao Y (2008) Nitrogen-doped carbon nanostructures and their composites as catalytic materials for proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Appl Catal B Environ 79:89–99

Odom TW, Huang J-L, Kim P, Lieber CM (2000) Structure and electronic properties of carbon nanotubes. ACS Publications, Washington, pp 2794–2809

Old DW, Wolfe JP, Buchwald SL (1998) A highly active catalyst for palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions: room-temperature Suzuki couplings and amination of unactivated aryl chlorides. J Am Chem Soc 120:9722–9723

Gholinejad M, Seyedhamzeh M, Razeghi M, Najera C, Kompany-Zareh M (2016) Iron oxide nanoparticles modified with carbon quantum nanodots for the stabilization of palladium nanoparticles: an efficient catalyst for the Suzuki reaction in aqueous media under mild conditions. ChemCatChem 8:441–447

Labulo AH, Omondi B, Nyamori VO (2018) Suzuki–Miyaura reaction and solventfree oxidation of benzyl alcohol by Pd/nitrogen-doped CNTs catalyst. J Mater Sci 53:15817–15836

Ombaka LM, Ndungu PG, Kibet J, Nyamori VO (2017) The effect of pyridinic- and pyrrolic-nitrogen in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes used as support for Pd-catalyzed nitroarene reduction: an experimental and theoretical study. J Mater Sci 52:10751–10765

Zhu Y, Yu G, Yang J, Yuan M, Xu D, Dong Z (2019) Biowaste soybean curd residue-derived Pd/nitrogen-doped porous carbon with an excellent catalytic performance for phenol hydrogenation. J Colloid Interface Sci 533:259–267

Gong K, Du F, Xia Z, Durstock M, Dai L (2009) Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 323:760–764

Sharifi T, Hu G, Jia X, Wågberg T (2012) Formation of active sites for oxygen reduction reactions by transformation of nitrogen functionalities in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 6:8904–8912

Arrigo R, Hävecker M, Schlögl R, Su DS (2008) Dynamic surface rearrangement and thermal stability of nitrogen functional groups on carbon nanotubes. Chem Commun 40:4891–4893

Arjmand M, Sundararaj U (2015) Effects of nitrogen doping on X-band dielectric properties of carbon nanotube/polymer nanocomposites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 7:17844–17850

Van Dommele S, Romero-Izquirdo A, Brydson R, De Jong K, Bitter J (2008) Tuning nitrogen functionalities in catalytically grown nitrogen-containing carbon nanotubes. Carbon 46:138–148

Pels J, Kapteijn F, Moulijn J, Zhu Q, Thomas K (1995) Evolution of nitrogen functionalities in carbonaceous materials during pyrolysis. Carbon 33:1641–1653

Shi W, Li J, Polsen ES, Oliver CR, Zhao Y, Meshot ER et al (2017) Oxygen-promoted catalyst sintering influences number density, alignment, and wall number of vertically aligned carbon nanotubes. Nanoscale 9:5222–5233

Zhang G, Mann D, Zhang L, Javey A, Li Y, Yenilmez E et al (2005) Ultra-high-yield growth of vertical single-walled carbon nanotubes: hidden roles of hydrogen and oxygen. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102:16141–16145

Wen Q, Qian W, Wei F, Liu Y, Ning G, Zhang Q (2007) CO2-assisted SWNT growth on porous catalysts. Chem Mater 19:1226–1230

Ombaka LM, Ndungu PG, Nyamori VO (2015) Pyrrolic nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes: physicochemical properties, interactions with Pd and their role in the selective hydrogenation of nitrobenzophenone. RSC Adv 5:109–122

Arrigo R, Schuster ME, Xie Z, Yi Y, Wowsnick G, Sun LL et al (2015) Nature of the N-Pd interaction in nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube catalysts. ACS Catal 5:2740–2753

Li M, Xu F, Li H, Wang Y (2016) Nitrogen-doped porous carbon materials: promising catalysts or catalyst support for heterogeneous hydrogenation and oxidation. Catal Sci Technol 6:3670–3693

Hummers WS Jr, Offeman RE (1958) Preparation of graphitic oxide. J Am Chem Soc 80:1339

Labulo AH, Ngidi NP, Omondi B, Nyamori VO (2018) Physicochemical properties of nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes from metallocenes and ferrocenyl imidazolium compounds. J Organomet Chem 868:66–75

Oosthuizen RS, Nyamori VO (2012) Heteroatom-containing ferrocene derivatives as catalysts for MWCNTs and other shaped carbon nanomaterials. Appl Organomet Chem 26:536–545

Wang B, Li J, Liu Y, Gao Y (2017) Reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanotubes nanohybrids as preformed reinforcement for polystyrene composites. J Appl Polym Sci 134:45054

Núñez JD, Benito AM, Rouzière S, Launois P, Arenal R, Ajayan PM et al (2017) Graphene oxide–carbon nanotube hybrid assemblies: cooperatively strengthened OH–O = C hydrogen bonds and the removal of chemisorbed water. Chem Sci 8:4987–4995

Yao T, Zhang J, Zuo Q, Wang H, Wu J, Zhang X et al (2016) A simple way to prepare reduced graphene oxide nanosheets/Fe2O3-Pd/N-doped carbon nanosheets and their application in catalysis. J Colloid Interface Sci 468:62–69

Yi M, Shen Z, Ma S, Zhang X (2012) A mixed-solvent strategy for facile and green preparation of graphene by liquid-phase exfoliation of graphite. J Nanopart Res 14:1003

Li D, Müller MB, Gilje S, Kaner RB, Wallace GG (2008) Processable aqueous dispersions of graphene nanosheets. Nat Nanotechnol 3:101

Amadou J, Chizari K, Houlle M, Janowska I, Ersen O, Begin D et al (2008) N-doped carbon nanotubes for liquid-phase CC bond hydrogenation. Catal Today 138:62–68

Liu S, Tian M, Yan B, Yao Y, Zhang L, Nishi T et al (2015) High performance dielectric elastomers by partially reduced graphene oxide and disruption of hydrogen bonding of polyurethanes. Polymer 56:375–384

Chen Z-L, Kam F-Y, Keerthi V, Song J, Hu C, Wong L-Y et al (2013) Efficient surfactant-free and chemical reductant-free solvothermal deoxidation of solution-processable sub-stoichiometric graphene oxide. J Mater Chem C 1:7246–7254

Marcano DC, Kosynkin DV, Berlin JM, Sinitskii A, Sun Z, Slesarev A et al (2010) Improved synthesis of graphene oxide. ACS Nano 4:4806–4814

Mombeshora ET, Ndungu PG, Jarvis A, Nyamori VO (2017) Oxygen-modified multiwalled carbon nanotubes: physicochemical properties and capacitor functionality. Int J Energy Res 41:1182–1201

Lin ML, Wu JB, Liu XL, Tan PH (2017) Probing the shear and layer breathing modes in multilayer graphene by Raman spectroscopy. J Raman Spectrosc 49:19–30

Kim KS, Um YM, J-r Jang, Choe W-S, Yoo PJ (2013) Highly sensitive reduced graphene oxide impedance sensor harnessing π-stacking interaction mediated direct deposition of protein probes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 5:3591–3598

Ansaldo A, Bondavalli P, Bellani S, Del Rio Castillo AE, Prato M, Pellegrini V et al (2017) High-power graphene–carbon nanotube hybrid supercapacitors. ChemNanoMat 3:436–446

Dresselhaus MS, Jorio A, Hofmann M, Dresselhaus G, Saito R (2010) Perspectives on carbon nanotubes and graphene Raman spectroscopy. Nano Lett 10:751–758

Malard L, Pimenta M, Dresselhaus G, Dresselhaus M (2009) Raman spectroscopy in graphene. Phys Rep 473:51–87

Ferrari AC, Basko DM (2013) Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat Nanotechnol 8:235

Nie R, Shi J, Du W, Ning W, Hou Z, Xiao F-S (2013) A sandwich N-doped graphene/Co3O4 hybrid: an efficient catalyst for selective oxidation of olefins and alcohols. J Mater Chem A 1:9037–9045

Saleh TA (2011) The influence of treatment temperature on the acidity of MWCNT oxidized by HNO3 or a mixture of HNO3/H2SO4. Appl Surf Sci 257:7746–7751

Chen X, Wu G, Chen J, Chen X, Xie Z, Wang X (2011) Synthesis of “clean” and well-dispersive Pd nanoparticles with excellent electrocatalytic property on graphene oxide. J Am Chem Soc 133:3693–3695

Lowell S, Shields JE (2013) Powder surface area and porosity, vol 2. Springer, Berlin

Yang S, Feng X, Wang L, Tang K, Maier J, Müllen K (2010) Graphene-based nanosheets with a sandwich structure. Angew Chem Int Ed 49:4795–4799

Zhang D, Yan T, Shi L, Peng Z, Wen X, Zhang J (2012) Enhanced capacitive deionization performance of graphene/carbon nanotube composites. J Mater Chem 22:14696–14704

Yan D, Xu X, Lu T, Hu B, Chua DH, Pan L (2016) Reduced graphene oxide/carbon nanotubes sponge: a new high capacity and long life anode material for sodium-ion batteries. J Power Sources 316:132–138

Kumar N, Huang C-W, Yen P-J, Wu W-W, Wei K-H, Tseng TY (2016) Probing the electrochemical properties of an electrophoretically deposited Co3O4/rGO/CNTs nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. RSC Adv 6:60578–60586

Wang Y, Shi Z, Huang Y, Ma Y, Wang C, Chen M et al (2009) Supercapacitor devices based on graphene materials. J Phys Chem C 113:13103–13107

Jung N, Kwon S, Lee D, Yoon DM, Park YM, Benayad A et al (2013) Synthesis of chemically bonded graphene/carbon nanotube composites and their application in large volumetric capacitance supercapacitors. Adv Mater 25:6854–6858

Chastain J, King RC, Moulder J (1992) Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: a reference book of standard spectra for identification and interpretation of XPS data: physical electronics division. Perkin-Elmer Corporation Eden Prairie, Minnesota

Wang P, Liu H, Liu M, Li R, Ma J (2014) Immobilized Pd complexes over HMMS as catalysts for Heck cross-coupling and selective hydrogenation reactions. New J Chem 38:1138–1143

You L, Zhu W, Wang S, Xiong G, Ding F, Ren B et al (2016) High catalytic activity in aqueous Heck and Suzuki–Miyaura reactions catalyzed by novel Pd/Ln coordination polymers based on 2,2′-bipyridine-4,4′-dicarboxylic acid as a heteroleptic ligand. Polyhedron 115:47–53

Fu W, Zhang Z, Zhuang P, Shen J, Ye M (2017) One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of magnetically recoverable palladium/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites and its catalytic applications in cross-coupling reactions. J Colloid Interface Sci 497:83–92

Bahrami K, Kamrani SN (2017) Synthesis, characterization and application of graphene palladium porphyrin as a nanocatalyst for the coupling reactions such as Suzuki–Miyaura and Mizoroki–Heck. Appl Organomet Chem 32:4102

Hezarkhani Z, Shaabani A (2016) Palladium(II) tetrasulfophthalocyanine covalently immobilized on keratin protein grafted graphene oxide nanosheets as a new high-performance catalyst for C–C coupling reactions. RSC Adv 6:98956–98967

Tonks L, Anson MS, Hellgardt K, Mirza AR, Thompson DF, Williams JM (1997) Palladium catalysed Heck reactions and allylic substitution reactions using glass bead technology. Tetrahedron Lett 38:4319–4322

Djakovitch L, Koehler K (2001) Heck reaction catalyzed by Pd-modified zeolites. J Am Chem Soc 123:5990–5999

Hagiwara H, Sugawara Y, Isobe K, Hoshi T, Suzuki T (2004) Immobilization of Pd(OAc)2 in ionic liquid on silica: application to sustainable Mizoroki − Heck reaction. Org Lett 6:2325–2328

Mori K, Yamaguchi K, Hara T, Mizugaki T, Ebitani K, Kaneda K (2002) Controlled synthesis of hydroxyapatite-supported palladium complexes as highly efficient heterogeneous catalysts. J Am Chem Soc 124:11572–11573

Yan Y, Liu S, Hao F, Liu P, Ha Luo (2014) Nitrocyclohexane hydrogenation to cyclohexanone oxime over mesoporous carbon supported Pd catalyst. Catal Commun 50:9–12

Zhang Y, Hou F, Tan Y (2012) CeO2 nanoplates with a hexagonal structure and their catalytic applications in the highly selective hydrogenation of substituted nitroaromatics. Chem Commun 48:2391–2393

Feng J, Handa S, Gallou F, Lipshutz BH (2016) Safe and selective nitro group reductions catalyzed by sustainable and recyclable Fe/ppm Pd nanoparticles in water at room temperature. Angew Chem Int Ed 55:8979–8983

Huang H, Wang X, Tan M, Chen C, Zou X, Ding W et al (2016) Solvent-free selective hydrogenation of nitroarenes using nanoclusters of palladium supported on nitrogen-doped ordered mesoporous carbon. ChemCatChem 8:1485–1489

Nişancı B, Turgut M, Sevim M, Metin Ö (2017) Three-component cascade reaction in a tube: in situ synthesis of Pd nanoparticles supported on mpg-C3N4, dehydrogenation of ammonia borane and hydrogenation of nitroarenes. ChemistrySelect 2:6344–6349

Tian M, Cui X, Dong C, Dong Z (2016) Palladium nanoparticles dispersed on the hollow aluminosilicate microsphere@ hierarchical γ-AlOOH as an excellent catalyst for the hydrogenation of nitroarenes under ambient conditions. Appl Surf Sci 390:100–106

Duan Y, Zheng M, Li D, Deng D, Wu C, Yang Y (2017) Synthesis of Pd/SBA-15 catalyst employing surface-bonded vinyl as a reductant and its application in the hydrogenation of nitroarenes. RSC Adv 7:3443–3449

Shil AK, Sharma D, Guha NR, Das P (2012) Solid-supported Pd (0): an efficient recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for chemoselective reduction of nitroarenes. Tetrahedron Lett 53:4858–4861

Jiao N, Li Z, Xia C, Liu J (2017) Palladium nanoparticles immobilized on cross-linked polymeric ionic liquid material: application as an efficient and recoverable catalyst for the hydrogenation of nitroarenes. ChemistrySelect 2:4545–4556

Liu C, Tan R, Yu N, Yin D (2010) Pt–Pd bi-metal nanoparticles captured and stabilized by imine groups in a periodic mesoporous organosilica of SBA-15 for hydrogenation of nitrobenzene. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 131:162–169

Yu X, Wang M, Li H (2000) Study on the nitrobenzene hydrogenation over a Pd-B/SiO2 amorphous catalyst. Appl Catal A Gen 202:17–22

Yi DK, Lee SS, Ying JY (2006) Synthesis and applications of magnetic nanocomposite catalysts. Chem Mater 18:2459–2461

Sangeetha P, Shanthi K, Rao KR, Viswanathan B, Selvam P (2009) Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene over palladium-supported catalysts—effect of support. Appl Catal A Gen 353:160–165

Guin D, Baruwati B, Manorama SV (2007) Pd on amine-terminated ferrite nanoparticles: a complete magnetically recoverable facile catalyst for hydrogenation reactions. Org Lett 9:1419–1421

Wang Y, Dou L, Zhang H (2017) Nanosheet array-like palladium-catalysts Pd x/rGO@ CoAl-LDH via lattice atomic-confined in situ reduction for highly efficient Heck coupling reaction. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9:38784–38795

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN). The authors are grateful to the School of Chemistry and Physics at UKZN for creating the conducive research environment. AHL is grateful to Prof. Bice Martincigh and Mrs Rasheedah Labulo for proofreading this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Labulo, A.H., Omondi, B. & Nyamori, V.O. Graphene/pyrrolic-structured nitrogen-doped CNT nanocomposite supports for Pd-catalysed Heck coupling and chemoselective hydrogenation of nitroarenes. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 142 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-018-0146-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-018-0146-0