Abstract

It is generally accepted that many of today’s classrooms have been nurtured by technological advances. Similarly, in language teaching contexts, automated machine translation is widely recognised as one of the most significant breakthroughs in digital technology, contributing to an increase in L2 students’ use of Google Translate (GT) to cope with language issues. Previous research found that, despite other technology already incorporated into classrooms, language teachers were still skeptical of students’ use of GT to do assignments. This study therefore explored students’ perceptions of the explicit use of GT to solve language problems in their classrooms. Data were obtained from an online survey distributed to students in an English course that gives them the freedom to make use of tools and deploy any strategy that enables intelligible communication. The findings from the keyword analysis indicated that the students held a positive attitude towards getting permission to use GT in their classrooms, and that they used GT for a wide range of purposes, in addition to translation. Given the real-world use of GT, this study posits that rather than restricting the use of the tool, teachers should adopt GT in their classes and guide students through the critical use of GT.

摘要

大家普遍接受今日許多教室都受到科技進步的養護。同樣地,在語言教學的情境下,自動翻譯被廣泛認為是數位科技最重要的突破之一,促使更多L2學生使用Google翻譯(GT)來處理語言的問題。之前的研究發現,儘管其他的科技已融入課堂中,語言教師仍對學生使用GT做作業抱持懷疑的態度。因此,本研究探討了學生對在課堂上明確使用GT來解決課堂上的語言問題的看法。數據來自一份線上問卷,問卷發放給一門英語課的學生,該課程給予學生利用工具和安排任何策略的自由,讓他們能夠達到可理解的溝通。關鍵詞分析的研究結果顯示,學生對獲得在課堂上使用GT的許可抱持正面的態度,而且除了翻譯以外,他們還將GT用於廣泛的用途。有鑒於GT的實際使用,本研究認為教師不應該限制工具的使用,而應該在課堂中採用GT,並且引導學生批判性地使用GT。

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It is commonly believed that the goal of learning English is to become proficient in the language, particularly to be able to use the language to achieve communicative goals. With limited vocabulary knowledge, however, gaining English input and conveying ideas in a foreign language is a challenge for many L2 learners. Today’s L2 learners, as digital natives, usually turn to automated translation tools to get the meanings of unfamiliar words, and the most commonly used of these is Google Translate (GT) (Bahri & Mahadi, 2016; Tsai, 2019). The existing literature on GT is substantial and focuses specifically on language learner strategy (i.e. learners’ strategic use of the tool to solve particular language problems in their classroom assignments). These include, for example, the effectiveness of GT in academic writing (Groves & Mundt, 2015; Tsai, 2019), students’ perceptions and use of GT (Kol et al., 2018), and teachers’ perspectives regarding students’ use of GT in their EFL classrooms (Stapleton & Kin, 2019).

The widespread use of GT among L2 learners thus stimulated discussions regarding the utilisation of machine translation as a pedagogical tool in language classrooms in much of the relevant research (Jolley et al., 2015). The findings in the previous studies, nonetheless, were primarily based on the teachers’ perspectives on the issues. Overall, it appears that teachers were largely skeptical about students’ use of GT as a tool for language learning use (e.g. Briggs, 2018; Stapleton & Kin, 2019), which contradicts existing evidence suggesting that GT could be a helpful language learning tool in and beyond the classroom (Josefsson, 2011). Given this mismatch between the technologies that continue to mature and the instructors’ beliefs regarding the use of readily available resources, scholars pointed out that teachers should reconsider their existing teaching methodologies to take advantage of and include more recently introduced materials in their language pedagogy (Golonka et al., 2014).

Motivated by a lack of current research into students’ perceptions of implementing GT in their EFL classroom, as well as the assertion that students are the best data sources that can provide truthful information about their school and their learning (Kozol, 2005), this study seeks to explore students’ opinions about the explicit use of GT in their EFL classroom as a strategy to solve language problems and to deal with language issues in an English course. Employing keyword analysis as an approach to analyse the data, this study will highlight key issues in the survey data, given that keyword analysis will reflect “what the text is really about, avoiding trivial insignificant details” (Scott & Tribble, 2006, pp. 55–56).

Literature Review

Background of GT

In recent years, the emergence of online machine translation (MT) technologies has supplanted most of the roles that traditional dictionaries had played in the classroom for decades. This is because, in addition to embracing technological advancements, many students find the use of paper-based dictionaries to be time-consuming (Alhaisoni & Alhaysony, 2017). GT, among the existing online machine translators, is the most commonly used translation tool among students for identifying word meanings due to its ease of use and ability to automatically and directly translate students’ L1 into another language (Briggs, 2018). Despite its popularity, accuracy remains a major drawback of GT (Lee, 2020), and that has been a persistent concern in many prior studies on students’ use of GT (e.g. Briggs, 2018; Tsai, 2019). Evidence suggested that GT was far from producing accurate, error-free translations (Groves & Mundt, 2015). As such, it should be stressed that, because the goal of GT is to provide only usable translations (Lewis-Kraus, 2016), users should not expect GT to replace humans in translation, especially in the contexts where the language produced should be accurate, and is expected to be extensive.

Ten years after its initial release in 2006, GT was significantly improved to integrate a new system that employs Artificial Intelligence (AI), labelled Google Neutral Machine (GNMT), as the major mechanics that could translate beyond sentence by sentence (Johnson et al., 2017). This cutting-edge training technique enables GT to learn from millions of texts in its database (Kol et al., 2018), resulting in better translation quality that reduced errors by 60 percent when compared to its previous version (Wu et al., 2016).

GT in Language Learning and Teaching

Given the popularity of GT among L2 learners, examinations of students’ perceptions of GT are becoming prevalent, as reflected in the growing body of research in this area. According to the prior research, students were generally satisfied with using GT as a strategy to deal with language problems (Al-Musawi, 2014), and they were thus inclined to continue using GT even if it was directly against their teachers’ advice (Garcia & Pena, 2011). More specifically, Jin and Deifell (2013), for example, argued that students felt it improved their writing and reading skills in the foreign language, while also reducing their anxiety about using the foreign language. Similarly, students in the study of Bahri and Mahadi (2016) reported that GT could enhance their self-learning, particularly in terms of gaining new vocabulary, aiding with writing, and facilitating reading in Bahasa Malaysia. Lastly, when the overall opinions about GT of English major students and non-English major students were compared, it was discovered that non-English major students, given their lower English proficiency, were more willing to continue using GT than English major students (Tsai, 2020). While the evidence about the association between students’ use of GT and their learning outcome remains limited, several scholars have confirmed that, in terms of language use, GT helped students write better, both quantitatively (they could write more words and longer sentences) and qualitatively (they could compose sentences with greater syntactic complexity and accuracy) than those who did not use GT (Cancino & Panes, 2021; Kol et al., 2018).

Regardless of the students’ overall satisfaction with GT, as for teachers’ reactions to the automated translation tools, many earlier studies argued that language teachers were not convinced that GT and other such tools could foster language learning. With the shift to communicative language teaching, the use of translation from one language to another language as a pedagogical practice became obsolete. Translation in language learning does not appear to fit today’s philosophy of language teaching (Cancino & Panes, 2021), due to its direct association with the outdated grammar-translation method and its emphasis on form (Cook, 2009). Scholars therefore generally advised against the implementation of GT in the language classroom (Fountain et al., 2009). This has contributed to the prohibition of the use of GT and other machine translation systems in some classrooms.

Many teachers’ misconceptions about their students’ use of GT to deal with language problems are also worrying. That is, some teachers assume that all students using GT would blindly copy the translations to do classroom tasks, given that GT and other available automated translation machines allow users to simply take L1 words and sentences to be translated. For this reason, the use of GT has generally been associated with students’ laziness (Praag & Sanchez, 2015). More worryingly, some teachers have said that the use of GT could lead to academic dishonesty (Clifford et al., 2013), so they felt that using the tool to do classroom tasks was wholly unethical (Jin & Deifell, 2013). From these perspectives, it is clear that many teachers would prohibit students from using GT, especially to do the assignments in their classes.

All these arguments clearly demonstrate that there is a mismatch between the instructors’ beliefs about students’ use of GT and how students actually used the tool. Nonetheless, since various studies in this area have stressed that students would continue to use the tool even if it contradicts their instructors’ views (White & Heidrich, 2013), teachers should avoid jumping to the conclusion that students would use GT mindlessly (Bin Dahmash, 2019). Rather than just advising students not to use the tool, teachers should help students strategically employ the available resources, including the judicious use of GT, in order to address the actual needs of the students in using the language in real-world situations (Cook, 2010).

The Use of GT to Cope with Language Problems

Despite the scarcity of existing in-depth investigations into what specific language issues have prompted L2 learners to turn to GT, it is generally argued that the tool has been used primarily to cope with vocabulary issues, or more specifically, to translate unknown words. While previous discussions pertaining to the use of GT largely focused on L2 learners using the tool to get the meanings of words, Tsai (2020) pointed out that the use of GT among Chinese students to translate words was mostly to complete writing assignments. Moreover, it is particularly important to note that many students would prefer to use GT to translate individual words rather than a whole paragraph (Jolley et al., 2015).

GT, in addition, has been used as a spelling checker. Employing interviews, observations, and an online log, Bin Dahmash (2019) argued that Saudi undergraduate students used GT to correct their English spelling. In particular, the author maintained that the participants used GT as a spell-checking tool in two ways. First, they would type an English word to see if the tool showed the translation (meaning that if the word is translated, it must be spelled correctly). Another way involved writing an Arabic word and then looking up the proper spelling of the translated English word. Overall, even though the specific language use contexts of GT among learners remain rather unclear, it is obvious that, on the whole, learners have used GT to cope with language issues related to their vocabulary use.

Methodology

Focus of the Study

The evidence presented above indicates that much of the existing research has focused on L2 learners’ and language teachers’ beliefs about the use of GT in a variety of contexts and issues. In Thailand, as was found in many other previous studies, Thai students considered GT to be helpful for their language learning, especially vocabulary learning (Sukkhwan & Sripetpun, 2014). To date, while most research has focused on students’ perceptions of GT and other translation tools in general, the evidence of their perceptions of being encouraged to use GT in language classrooms to solve language issues remains unclear. Consequently, with little information provided in previous research, conducting a study that investigates students’ perceptions of the explicit use of GT in their EFL class to do classroom tasks, as well as how they used it to solve language problems, becomes paramount. To gain insights into the issues, this research formulated these research questions:

-

1.

What are the students’ beliefs about getting explicit permission and training from their teachers to use GT as a resource in their EFL classroom to deal with language issues?

-

2.

What particular language issues compel students to use GT?

Participants and the Study Context

The current study included 105 Thai undergraduate students, all between the ages of 19 and 20, from a Thai technological university’s international programme in the Faculty of Engineering. Their individual levels of English proficiency slightly differed, but given the university’s standard English language proficiency requirement, the majority entered the university with a proficiency level of B1 or B2 according to the CEFR framework.

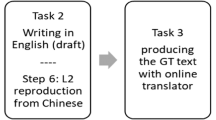

All participants had previously completed the English fundamental course for students in an international programme. This course was especially aimed to promote students’ intrinsic motivation to use English. To this end, in the course, termed the hobby course, the lessons were structured around the topics of doing a hobby, with each student choosing a different hobby and exploring different resources to do their hobby. With the differences in the exposures to English input, giving students flexibility and the freedom to exploit any strategies that enable successful communication, and to use any available tools and resources to successfully do things (related to their hobby) in English, was the major focus of the course. The topics in the course primarily included students communicating about their hobby with other hobby enthusiasts on a Reddit forum, and presenting their hobby to the world (through an online video sharing platform). For the students to effectively make use of tools, there was one lesson devoted to training and guiding students on how to use GT as well as issues related to the translation tool (e.g. benefits and limitations). Throughout the course, students gained the freedom to use GT to solve language problems (e.g. reading Reddit rules and other texts about their hobby) and do other classroom assessments.

Data Collection

The data gathered in this study was from an online questionnaire survey. The survey was designed to elicit students’ opinions on the explicit use of GT in their English classroom as a resource to complete classroom tasks. The questionnaire was presented as a Google Form, with all information and items written in English. The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section sought consent from participants, explaining the purposes of the study and giving assurance of the confidentiality of their data. They were also informed that by submitting their responses, they were giving the researcher permission to use their data in the study. The second section, which included two open-ended questions, asked them to comment on certain issues which were the major focus of this study. More specifically, in the questionnaire, they were asked to give responses to the following questions: (1) what do you think about getting permission from your teacher to use Google Translate in your English classroom? (2) What language problems or issues have you usually coped with by using Google Translate? Both questions were associated with the two research questions. The data gathered from the students’ responses were purely qualitative.

To begin collecting the data, the teachers of the course were first contacted and asked to distribute the survey to the students in their classes. While it was explicitly stated in the questionnaire that the students’ responses would be anonymous, the teachers were asked to remind their students that their participation was entirely voluntary, and that whether or not they chose to participate in the survey would have no effect on their grades. Eventually, a total of 105 students completed the questionnaire survey.

Data Analysis

The qualitative comments were analysed quantitatively and qualitatively. To analyse the data, the researcher used a corpus-based approach, treating the students’ responses to the two open-ended questions as two separate corpora (students’ perceptions corpus and use corpus). The corpus-based technique has been used in a wide range of studies where salient concepts in texts are the main concerns. For instance, to examine the teachers’ perceptions of the shift from classroom teaching to online teaching, Watson Todd (2020) employed a corpus-based analysis to analyse survey data and develop themes of key concerns among the teachers, with quotations used to illustrate each area of concern. In addition, given the various applications of the method, a corpus-based technique was used to analyse published papers to investigate how the roles of teachers and students had changed in formal education contexts (Thomas et al., 2019).

In this study, keyword analyses were used to compare one target corpus (the students’ beliefs corpus and the use corpus) against the benchmark corpus to determine words in the target corpus that were used significantly more frequently than words in the benchmark corpus. This is technically referred to as keyness, suggesting what the text is about (Lewis-Kraus, 2016). Log-likelihood (LL) tests were then calculated to determine whether the words identified as keywords happened by chance (Pojanapunya & Watson Todd, 2018), meaning that the higher the LL value is, the more salient the word is in one target corpus compared to another corpus. Each of the two target corpora was then compared against the British National Corpus (BNC) using the KeyBNC software (Graham, 2014). The BNC, representing general English usage, provides a wide coverage of texts in both spoken and written language and is not limited to any particular subject area, making it an appropriate reference corpus used to identify key aspects of the data in this study. The keyword list, automatically generated from the software, was then investigated to determine the threshold value. From the investigation into the list, given that words which appeared only once or twice in the list did not appear to be significant or meaningful, the minimum frequency threshold was set at three (meaning that only words which appeared more than two times were considered key). Finally, to elicit as many relevant aspects in the comments as possible, the top 10 keywords ranked by LL value were considered to be key for this study.

Adhering to the procedures of qualitative data analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), thematic analysis was conducted to identify salient patterns across the qualitative data to derive themes. First, the top 10 keywords and keyword concordance lines (using the AntConc software) (Anthony, 2019) were observed and thoroughly examined. It should be noted that, as Pojanapunya (2016) cautioned, follow-up methods of keyword analysis, such as the use of concordance lines, should be carried out to identify the conceptual associations between the keywords when the resulting keywords fail to indicate what the corpus is about. Then, from the investigations, the top 10 keywords in each corpus were categorised to thematise the students’ comments given in the survey. Following the thematic analysis, the comments were read carefully, thoroughly selected to avoid redundancies, and used to illustrate and interpret the students’ perceptions of using GT in the classrooms and how they used the tool.

Results

The following sections report the findings from the analyses. The author has classified the findings according to the research questions, including the students’ perceptions of explicit use of GT in the classroom and how they used the tool to solve language problems.

Students’ Comments on Explicit Use of GT in Their EFL Classroom

The students’ beliefs corpus was compared against the BNC corpus to highlight the students’ opinions about the explicit use of GT in their classroom. The top 10 highest-ranked keywords are presented in Table 1.

One remarkable pattern emerges from the identified keywords in Table 1: the majority of the words considered to be key are those that denote either judgements (good and correct) or actions (think, can, help, and understand). This is particularly reasonable as the students mainly addressed what they believed about using GT explicitly in the classroom (words related to students’ judgements), as well as how GT as a translation tool would function in their classroom. To gain insights into how students perceived the explicit use of GT in their classroom, three of the 10 keywords were classified as overall perceptions of implementing GT in the EFL classroom, four as how students could benefit from the use of GT in the classroom, and three as their recommendations.

Overall Perceptions

The keywords for this category include think, good, and correct. Many of the sample quotations indicate that learners had a positive attitude when it came to obtaining permission to use GT in the classroom. For example, students agreed that, given its widespread use in the real world, GT is a tool that should also be implemented in the language classroom: “Nowadays GT have used by most people and students so I think it can implement in our classroom in some ways”. Many students said that they preferred to use the tool in the classroom because they “think that it is good, comfortable, fast”, and they also “think it’s good, it gives us some new vocabulary and practice thinking and have more learning help”. While the majority of students believed that the benefits of having the freedom to use GT to solve language problems outweigh its limitations (e.g. “I think many benefits from GT, but there are some errors, but overall it was good idea to implement in class”), some were aware of the inaccuracies, thus arguing that students should not rely on GT entirely: “think it can sometimes help. Although it sometimes translates in a strange way, but we should try to change it to make it correct according to what we learned or what we know”. From these comments, it appears that the students believed that, since GT is already being used in the real world, its use should also be allowed in the classroom to do particular language tasks.

The students’ judgements about GT also arose in the data. The participants on the whole recognised GT as a useful tool: “It is very good”. More specifically, they thought that it could help them expand their vocabulary, saying: “In my opinion, it is good to have GT as a vocabulary teacher but I feel that it is not capable of translating the whole sentence or books” and “It’s good cause GT not too bad to translate word by word”. On the one hand, GT is readily available, making it easy to use. On the other hand, it should be used critically, otherwise, “I don’t think it’s very good for help in learning a language, knowing a meaning of a word means nothing if you don’t know how or when to use so everyone should use it properly”. Most importantly, we should be aware that “some translations may not be correct, it may result in a decrease in the score”.

The Benefits of GT in Classroom Contexts

The issue as to how students perceived the benefits of GT in a language classroom was also prominent in the survey data. The keywords which fall into this category include can, help, words, and understand. On the whole, they believed that GT offers a wide range of applications, aiding students with their language use and learning strategy, saying, “We can use Google Translate to find synonyms words”, and “can learn how to pronounce some words from Google Translate”. In classroom contexts, although the participants were in an international programme, they found GT to be particularly useful in the classroom to gain a better understanding of the lessons which were delivered in English: “Google Translate can be used in the classroom. Because we must translate words a lot in the classroom”. Similarly, one student stated, “If using in the English language curriculum, it is possible to help students understand the meaning”. These students’ arguments are particularly compelling, given that “We are not the native speaker so there will be some words that we can’t understand even if the teacher explain in detail”. It should be noted that, from the identified keywords, GT was generally used to translate individual words, rather than other complex lexical units (e.g. idioms and technical terms). Given the context of English use in the hobby course, and the fact that they were first-year students when the study was conducted, the students may have had limited exposure to such extensive language production, and so using GT to translate such complex word units became unnecessary.

Suggestions

In the final sub-category, the investigations into the keyword concordance lines revealed that students make recommendations about how to use the tool in their language classroom. The keywords relevant to the issue include google, translate, and grammar. The fact that the students had actual experience with using GT in their language classroom enabled them to provide insightful recommendations on how to incorporate GT into a foreign language classroom. First, they suggested that teachers be involved in guiding students in the proper use of the tool, saying, “Maybe teacher lets students translate words and lets students think about translation is correct or not. Or teacher lets students make better translation than it”. Teachers are also expected to raise students’ awareness of the potential problems of using GT: “But students must also be educated about various grammar forms as google translate has certain kind of flaws” and “I want it to be used in the classroom and teach us how to use and correct when google translate doesn’t translate directly”. GT could also be used beyond a translation tool. One student pointed out that it could be used as part of a class activity: “Maybe we can have a game like challenge to translate word who are fastest and who get most answers correct will be win”. These comments obviously show that, despite their regular use of GT, students were concerned about some translation issues, and so they believed that language teachers should take part in giving students advice on using the tool judiciously.

Across all three subcategories, these responses reflect that the students agreed that GT was appropriate for use in their language classroom. They recognised the far-reaching applicability of GT in dealing with language issues in their classrooms. In addition, by addressing some drawbacks of GT and the need to be guided to use the tool appropriately, it is obvious that they were showing their awareness of the potential limitations of the translation tool, suggesting their high tendency to use the tool critically.

How Students Used GT to Solve Particular Language Problems

In addition to the students’ perceptions of using GT in the classroom, it is necessary to investigate how students decided to use GT to cope with specific language issues. Table 2 provides the top 10 keywords.

We might expect somewhat similar keywords in the two corpora (e.g. translate, google, and understand) since these words are most frequently used to describe students’ perceptions of GT as well as how they utilised the tool to solve particular language problems. A variety of viewpoints were expressed, yet the keyword analysis revealed two major broad themes. Concordances of the identified keywords suggest that the two key language problem areas include general language problems and specific problems.

General Language Issues

While the practical use of GT in specific problem areas is unequivocal in this theme, respondents generally agreed that GT is a translation tool useful for translating unknown words (keywords include translate, google, word, understand, meaning, and translation). When asked how they use GT to solve language problems, the students agreed that GT was typically used to look up meanings of words: “I used Google Translate when I want to know the meaning of word or phrases” and “I used the google translate to translate some word that I never know before”.

From a quick glance at the students’ responses, it appears that the comments were rather similar to those discussed in the preceding section on students’ beliefs about integrating GT in the classroom. This might be because, in this particular survey item, many students also briefly discussed the benefits of GT to support their arguments for incorporating it into the classroom. However, a deeper examination of the concordances revealed that, in this survey question, the majority offered detailed comments on how they decided to use GT to get the meanings of unknown words. The majority of students chose to translate one word at a time: “Only translate a single word” and “Try to translate word by word”. Some students, moreover, elaborated that they would rather use GT to translate a word, than a chunk of text: “I have only used google translate for a direct word-to-word translation, and not commonly in phrases, to solve particular wording issues”.

While most students turned to GT generally to get words translated, some decided to use the tool to double-check their understanding: “I have used Google Translate to cross check with my own knowledge of the word or with others’ translations before”. Another student, interestingly, noted that English translation from GT aids in the comprehension of some Thai words, particularly those that are not part of common terminology: “For example, there are special Thai words I fail to easily understand during my translation process, and Google translate can directly provide the translation of this word in English”. Together with its vast range of applications, GT is largely regarded as a competent automatic translation tool, given that, “Maybe it might not translate very directly, but the translation is useful cause you are able to understand”.

Other Language Issues

The keywords (including use, sentences, English, and Thai) provide the basis for the key areas of language issues solved by the use of GT. The analysis of keywords revealed that, overall, students used GT as a language use strategy. First, in a classroom context, they used the translation tool to deal with the problems related to their understanding of the classroom tasks and the teachers’ instructions. As a result, when students were having difficulty understanding English materials, they chose to use “Google Translate to translate the language when the teacher instructs you to read articles or give homework in English”. In addition, to ensure that their writing in assignments was precise and could effectively convey the intended messages, students usually sought help from GT: “I always use google translate with my work. To make me have more confident about my work that I write it on point or not. I will write my work in English first. And then translate to Thai to make me have more confident on my work for my writing assignments”. Some respondents, in addition to using GT in support of their assignments, used it to translate instructions given by their teachers for easier comprehension: “I would take the language that the teacher send us through our Line chat in English or do something in English to translate into Thai allowing us to understand and do what the instructor has given or want us to do”.

Communication issues are also particularly prominent in the students’ comments. A large number of respondents indicated that, if they had language problems during a conversation, they would seek assistance from GT. The use of GT, thus, enabled successful communication with interlocutors who came from different L1 backgrounds: “Sometimes I want to talk to foreign friends. I use a translator to help”, and some students recounted their experiences of using GT to help others: “I had a foreigner to ask for directions, some words I do not know, then use GT to help, enough to answer him”. Furthermore, the majority of students relied on GT to help them communicate effectively. Using GT to complete the survey of this study illustrated how students routinely utilised GT as a way to deal with daily language issues, as one student revealed, “For example, for completing this survey, I used Google Translate to help me compose sentences”. A number of students, besides, used GT in their recreational activity: “Like mentioned before, I often use them to translate manga [Japanese comics]. I would also look up English word in forum post and fan fiction that I’ve never seen before too”. Some students shared advice and their own experience with utilising GT as a communication strategy while overseas. That is, since “it requires a relatively high understanding of how to organize sentences, I often used it when I travel to new places without basic knowledge of the language in those country. I tried to use simple sentences so that it could translate it in a way that the local would understand well”.

Lastly, although the majority of students employed GT as a language use strategy, a minority of them seemed to utilise the tool as a learning strategy, particularly to deal with their pronunciation problems. This means that the students used GT to listen to the correct pronunciation of the translated words in order to improve their pronunciation: “Some word is hard to pronounce so I use google translate to help me to pronounce that word and try to pronounce that word too” and “use to practice pronunciation when coming across a strange vocabulary”.

Overall, the students used GT for a variety of reasons. Many students in fact used GT for purposes other than classroom assignments (e.g. for doing their hobby). Furthermore, despite the fact that many of them used the tool to solve language problems in order to complete their assignments, they did not appear to perform blind copying of the translations. Rather, they used it to confirm their understanding and increase their confidence in using the language.

Discussion and Conclusion

As GT becomes more popular and is widely used by today’s L2 learners, the present study sought to investigate students’ beliefs about using the tool to cope with language issues in their classrooms. This study indicated that the participants were generally enthusiastic about utilising GT to solve certain language tasks, which is consistent with the literature (e.g. Alhaisoni & Alhaysony, 2017). As a result, the identified keywords in this study, together with the students’ comments, demonstrated the students’ strong preference for the explicit use of GT in their language classroom. The students, in particular, believed that the tool could provide a wide range of applications, given certain identified keywords (e.g. can), and thus employing GT could be an effective strategy for dealing with language problems in their classroom (e.g. good and help).

Another notable conclusion from the keyword analysis is that the students appeared to recognise the possible problems associated with using the tool, particularly accuracy issues. Thus, the analysis suggested that the students did not rely solely on GT, especially while completing classroom assignments. The students’ tendency to not rely solely on GT is in line with other research (Al-Musawi, 2014), which has suggested that students should not rely extensively on the tool because they will eventually become habituated to using the tool and lose interest in learning the language. As the primary goal of this study was to identify the students’ perceptions towards the explicit use of GT, it is crucial to highlight that, in addition to their positive attitudes towards GT, students were also willing to seek advice from their teachers regarding the critical use of the tool. The fact that the students in this study had previously obtained the freedom to use GT to solve language problems in the English course could have a bearing on the students’ determination to be instructed by their teachers. That is, their actual experience of being allowed to use GT in their classroom would contribute to their propensity to see the importance of seeking assistance from their teachers on how to use the tool judiciously. Overall, the students showing a strong preference for using GT, a popular automated translation tool, and their awareness of the limitations of the tool clearly indicate that they are cautiously “jumping on the bandwagon”, as referenced in the title.

With respect to the second research question, it is apparent that GT was largely used to obtain definitions of unknown words and, in certain cases, to confirm their understanding. Despite some broad responses on how students used GT in classroom contexts, particular comments provided insights into how students decided to use GT to solve specific language problems. The areas of problems included both receptive and productive skills. According to Karimian and Talebinejad (2013), most students affirmed that translation was an effective strategy for dealing with reading comprehension problems. Similarly, it was revealed in this study that reading problems, both within and outside the classroom, were dominant in the data. With regards to writing skills, or the productive skills, as one participant mentioned, using GT could help the student gain more confidence in the writing tasks. This finding is consistent with that of Jin and Deifell (2013), previously discussed in the review of literature, that the students felt GT could reduce their fear of using a foreign language. The explanation for this result could be that, as Fredholm (2015) stated, the students’ use of GT to aid them with their writing allowed them to exhibit more lexical diversity. Having a variety of word choices may therefore increase students’ confidence in using the language.

One unanticipated finding, however, was that most students used the tool as a strategy for using the language. While it was commonly discovered in prior research on students’ use of GT that the students utilised the tool to assist their language learning, the students in this study mainly employed GT as a language use strategy. In contrast to the previous finding, which reported that students used GT mostly to learn English vocabulary, only one student in this study utilised GT as a vocabulary learning tool. This clearly suggests that the students in the present study would rather use GT to cope with language problems than to expand their vocabulary. It is therefore salient to note that, while it was discussed in much of the literature that teachers still held negative attitudes towards GT, the students in this study appear to be aware of how to use the tool appropriately and judiciously. According to the keyword analysis of the students’ responses, the students tended to consider GT as a supporting tool, and they seemed to use the tool critically. It could be noticed from the quotations that the students were aware of the use of GT. This means that, for example, in situations where intelligible communication is more important than accuracy, students would rely on GT without being concerned about its inaccuracy (e.g. “I had a foreigner to ask for directions, some words I do not know, then use GT to help, enough to answer him”.) Nonetheless, when it came to using GT in the classroom, students were noticeably more cautious about its limitations (e.g. “Some translations may not be correct, it may result in a decrease in the score.”) All of these observations suggest that the students were suitably critical, and particularly choosy, about the use of GT to do particular language tasks.

As an approach to using the language, it appears that there is a wide range of benefits that students could get from employing GT. As a consequence, the findings of this study, which include both students’ opinions of GT and how they decided to use the tool to deal with specific language issues, cast doubt on authorities’ efforts to prevent the use of GT in the language classroom in order to conform to an outmoded worldview of students’ usage of a translation tool in their classroom. Since GT is already used worldwide and for a range of purposes, the present article argues that teachers should explicitly incorporate GT in their foreign language classrooms and teach students how to use the tool judiciously and appropriately. There are numerous approaches to guiding students, but one viable strategy is to provide them with some examples of GT mistranslations to highlight that GT is an excellent translation tool, but there are certain challenges and problems that students should be aware of. With this teaching method, students will genuinely realise that they should not depend entirely on GT to solve language problems.

While this study has covered extensive discussions on the issues relevant to students’ perceptions and their use of GT, there are some limitations that need to be addressed. The first issue concerns the language used in the survey questionnaire and the students’ responses. Given that some participants were international students (in the international programme at the university), and that the software used in this study only supported English texts, the questionnaire items and the responses of the students had to be written in English. As such, since English was not some of the participants’ first language, this could account for the challenges as to what words or keywords students would use in the questionnaire. As with the language issue, and probably with the nature of keyword analysis that focuses on breadth rather than depth, it appears that there was a lack of a holistic view in the qualitative comments on how students used GT, especially on the uses which could be considered as inappropriate by their teachers. This could be an area which future research may address, possibly by involving interviews for participants to discuss other key aspects, including students’ problematic use of GT in the EFL classrooms.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Alhaisoni, E., & Alhaysony, M. (2017). An investigation of Saudi EFL university students’ attitudes towards the use of Google Translate. International Journal of English Language Education, 5(1), 72–82. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijele.v5i1.10696

Al-Musawi, N. M. (2014). Strategic use of translation in learning English as a Foreign Language (EFL) among Bahrain University students. Innovative Teaching, 3, 4.

Anthony, L. (2019). AntConc 3.5.8 (Windows). [Computer program]

Bahri, H., & Mahadi, T. (2016). Google Translate as a supplementary tool for learning Malay: A case study at University Sains Malaysia. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 7(3), 161–167.

Bin Dahmash, N. (2019). Approaches to crafting english as a second language on social media: An ethnographic case study from Saudi Arabia. Arab World English Journal, 10(2), 136–150. https://doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol10no2.12

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Briggs, N. (2018). Neural machine translation tools in the language learning classroom: Students’ use, perceptions, and analyses. The JALT CALL Journal, 14(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.29140/jaltcall.v14n1.221

Cancino, M., & Panes, J. (2021). The impact of Google Translate on L2 writing quality measures: Evidence from Chilean EFL high school learners. System, 98, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102464

Clifford, J., Merschel, L., & Munnie, J. (2013). Surveying the landscape: What is the role of machine translation in language learning? Revista De Innovacion Educativa, 10, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.7203/attic.10.2228

Cook, G. (2009). Use of translation in language teaching. In M. Baker & G. Saldanha (Eds.), Routledge encyclopedia of translation studies (pp. 117–120). Routledge.

Cook, G. (2010). Translation in language teaching: An argument for reassessment. Oxford University Press.

Fountain, C., & Fountain, A. (2009). A new look at translation: Teaching tools for language and literature. In C. Wilkerson (Ed.), Empowerment through collaboration: Dimension 2009 (pp. 1–15). Valdosta.

Fredholm, K. (2015). Online translation use in Spanish as a foreign language essay writing: Effects on fluency, complexity and accuracy. Revista Nebrija De Lingüística Aplicada, 18, 7–24.

Garcia, I., & Pena, M. I. (2011). Machine translation-assisted language learning: Writing for beginners. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(5), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2011.582687

Golonka, E., Bowles, A., Frank, V., Richardson, D., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

Graham, D. (2014). KeyBNC (Windows). [Computer program]

Groves, M., & Mundt, K. (2015). Friend or foe? Google Translate in language for academic purposes. English for Specific Purposes, 37, 112–121.

Jin, L., & Deifell, E. (2013). Foreign language learners’ use and perception of online dictionaries: A survey study. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(4), 515–533.

Johnson, M., Schuster, M., Le, Q. V., Krikun, M., Wu, Y., Chen, Z., Thorat, N., Viegas, F., Wattenberg, M., Corrado, G., Hughes, M., & Google, J. D. (2017). Google’s multilingual neural machine translation system: Enabling zero-shot translation. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 5, 339–351.

Jolley, J. R., & Maimone, L. (2015). Free online machine translation: use and perceptions by Spanish students and instructors [Proceeding]. The 2015 Central States Conference on the Teaching of Foreign Languages, Minneapolis, United States.

Josefsson, E. (2011). Contemporary approaches to translation in the classroom: A study of students’ attitudes and strategies. 1–32, http://du.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:519125/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Karimian, Z., & Talebinejad, M. R. (2013). Students’ use of translation as a learning strategy in EFL classroom. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(3), 605–610. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.3.605-610

Kol, S., Schcolnik, M., & Spector-Cohen, E. (2018). Google Translate in academic writing courses? The EuroCALL Review, 26(2), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2018.10140

Kozol, J. (2005). The shame of the nation: The restoration of apartheid schooling in America. Crown Publishing.

Lee, S. M. (2020). The impact of using machine translation on EFL students’ writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(3), 157–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1553186

Lewis-Kraus, G. (2016). The great AI awakening. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/14/magazine/the-great-aiawakening.html

Pojanapunya, P. (2016). Clustering keywords to identify concepts in texts: An analysis of research articles in applied linguistics. rEFLections, 22, 55–70.

Pojanapunya, P., & Watson Todd, R. (2018). Log-likelihood and odds ratio: Keyness statistics for different purposes of keyword analysis. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory, 14(1), 133–167.

Scott, M., & Tribble, C. (2006). Textual patterns. Benjamin.

Stapleton, P., & Kin, B. L. K. (2019). Assessing the accuracy and teachers’ impressions of Google Translate: A study of primary L2 writers in Hong Kong. English for Specific Purposes, 56, 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2019.07.001

Sukkhwan, A., & Sripetpun, W. (2014). Use of Google Translate: A survey of Songkhla Rajabhat University students [Proceeding]. L-SA Workshop and Colloquium: “Speaking” for ASEAN, Songkhla, Thailand.

Thomas, N., Rose, H., & Pojanapunya, P. (2019). Conceptual issues in strategy research: Examining the roles of teachers and students in formal education settings. Applied Linguistics Review, [Advanced Access], 1–17

Tsai, S. C. (2019). Using google translate in EFL drafts: A preliminary investigation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(5–6), 510–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1527361

Tsai, S. C. (2020). Chinese students’ perceptions of using Google Translate as a translingual CALL tool in EFL writing. Computer Assisted Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1799412

Van Praag, B., & Sanchez, H. S. (2015). Mobile technology in second language classrooms: Insights into its uses, pedagogical implications, and teacher beliefs. ReCALL, 27(3), 288–303.

Watson Todd, R. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions of the shift from the classroom to online teaching. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 2(2), 4–16.

White, K. D., & Heidrich, E. (2013). Our policies, their text: German language students’ strategies with and beliefs about web-based machine translation. Die Unterrichtspraxis/teaching German, 46(2), 230–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/tger.10143

Wu, Y., Schuster, M., Chen, Z., Le, Q. V., Norouzi, M.,Macherey,W., Krikun, M., Cao, Y., Gao, Q., Macherey, K., Klingner, J., Shah, A., Johnson, M., Liu, X., Kaiser, Ł., Gouws, S., Kato, Y., Kudo, T., Kazawa, H., … Dean, J. (2016). Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.08144. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1609.08144

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Rangsarittikun, R. Jumping on the Bandwagon: Thai Students’ Perceptions and Practices of Implementing Google Translate in their EFL Classrooms. English Teaching & Learning 47, 511–527 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-022-00126-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-022-00126-5