Abstract

India has experienced a significant increase in income inequality in the past decade. It is widely accepted in the literature that income inequality is detrimental to individual health. Against this backdrop, the objective of the paper is to analyze the effect of income inequality on individual health status in the Indian context. We have examined two aspects: the impact of inequality on society in general and whether the effect of inequality is harsher on the poor as compared to the rich. We tested the income inequality hypothesis to answer the research questions. Using two rounds of India Human Development Survey data, a large-scale, nationally representative, panel data set collected in 2004–05 and 2011–12, we found a negative association between income inequality and individual health. Moreover, the poor are found to be the worst sufferers of income inequality and are more sensitive to ill health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The association between income inequality in a society and the poor health status of its people has attracted the attention of researchers from multiple disciplines. Equal societies are healthier as they have higher social cohesion, good social relation and less stress (Wilkinson 1996). People in such societies are offered more public goods, social support, social capital, and satisfies the citizens’ preference for fairness. On the contrary, people living in unequal societies suffer from poor health in general. Income poverty, along with inequality increases the risk of premature mortality and increased morbidity (Marmot 2002). Relative deprivation in society also causes ill health.

Many nations and regions across the world have observed a high level of income inequality in the past three decades. India is no exception to this; while the average household income has increased, so is income inequality. Soaring income inequality may have a negative impact on various aspects of human life and the economy. Our focus in this paper is to analyze the effect of income inequality on individual health.

We have used the income inequality hypothesis (IIH) to examine the relationship between income inequality and health. To be specific, we attempted to answer the following questions; does income inequality affect the individual health of Indians in general? Besides, does it affect the poor more compared to the rich? There are two distinct versions of IIH—strong and weak IIH. According to the strong version of IIH, income inequality is bad for society in general. At the same time, the weak IIH says that income inequality affects only the least well-off people in society. We have tested both the hypotheses. We have also explicitly tested whether income inequality has a harsher effect on the poorer sections of society since a considerable proportion of the Indian population lives below the poverty line. We used the India Human Development Survey data, a nationally representative panel data set, collected in 2004–05 and 2011–12 for analysis. Our study will be an important value addition in the related field of research in the Indian context, where very few studies attempted to answer these research questions, especially using the information on individual health status.

The paper is organized as follows. We have described the theoretical foundation and related literature in section “Income Inequality and Health: Theoretical Foundation and Relevant Literature” and the data and methodology in section “Data and Methodology”. Section “Results and Discussion” discusses the estimation results and section “Conclusions” provides the conclusions.

Income Inequality and Health: Theoretical Foundation and Relevant Literature

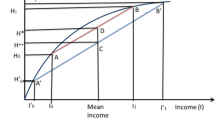

Individual income, like income inequality, is an influential determinant of individual health status. This has been broadly accepted in the relevant literature. It is established that the relationship between individual income and health status is concave, implying that each additional rupee of income will improve individual health by a decreasing amount. Subsequently, researchers have hypothesized that an aggregate relation between average health status and income inequality in a society can be observed if the underlying individual-level relationship between income and health is concave. Such concavity implies that transferring × amount of money from the rich to the poor will improve the average health status in society as the improvement in the health of a poor person more than offsets the loss in the health of a rich person. It is also possible not to incur any loss in the health of the rich by transferring income in the flat part of the curve (Subramanian and Kawachi 2004). Relevant literature has already established that a society with a narrower income distribution has a better average health status under ceteris paribus condition (Kawachi 2000).

On the contrary, if the relationship between individual health and individual income is linear or not concave, a transfer of income from the rich to the poor will reduce poverty. Still, there will not be any impact on the average health status of society. This expected relation between income distribution and average health status in society is termed as the “concavity effect” (Subramanian and Kawachi 2004). In addition to the concavity effect, there is another contextual independent effect of income inequality on health. Wagstaff and Doorslayer (2000) posit that apart from individual income or societal average income, income distribution plays an essential role in an unequal society where people suffer more from bad health. This effect is termed the “pollution effect” of income inequality on health (Subramanian and Kawachi 2004). These two effects distinguish between “concavity-induced income inequality effects” from “societal effect of income inequality”. We hypothesize that concavity effect, as well as pollution effect, holds in the Indian context where income inequality is quite high. We will test this hypothesis empirically.

To capture the “concavity effect” as well as the “pollution effect” of income inequality on individual health, we require multilevel data that includes information on individual income, along with details on the extent of income inequality in the society in which an individual resides.

The income inequality hypothesis (IIH) may be used to test these two effects—concavity and pollution—simultaneously, which may help to determine the independent as well as the relative importance of these two effects. We will test both strong and weak IIH in the Indian context to understand whether income inequality affect all individuals equally or it affects poor people more than the rich.

The earliest research paper studying the relationship between mortality and income inequality was written way back in 1979 (Rodgers 1979). After that, a series of studies have examined the association between income inequality and health across states or regions within different countries, for example, in the United Kingdom (Wilkinson 1992), the United States of America (Kaplan et al. 1996; Kawachi et al. 1997), Canada (Daly et al. 2001), Chile (Subramanian et al. 2003), Brazil (Rasella et al., 2013), Italy(De Vogli et al., 2005), Russia (Walberg et al.,), China (Pei and Rodriguez) and Japan (Kondo et al., 2008). A considerable number of research papers also addressed a similar research question through cross-country comparisons (Waldman 1992; Ross et al. 2000). Many of these studies focused on analyzing the relationship between income inequality and health status at the aggregate level. Aggregate health status is usually captured through life expectancy, infant mortality rate, death rate, etc. Some of the relevant literature also argued that the psycho-social theory plays a crucial role in determining the causality from income inequality to bad aggregate health in a society. According to the psycho-social school, income inequality causes a higher level of stress among the poor income group and damages their health either directly or indirectly through the development of unhealthy behaviour like alcohol consumption or smoking resulting from stress (Lynch et al. 2000; Murali and Oyebode 2004; Wilkinson 1996). Such behaviour is amplified at the aggregate society level through anti-social behaviour, which affects the health of individuals from other income groups, including rich ones. Therefore, it implies that non-materialistic pathways, along with materialistic ones, jointly determine the association between income inequality and health status. Surprisingly, Mellor and Milyo (2002) did not find any positive evidence in favour of the psycho-social theory in the context of the United States. They established that the psycho-social theory is not always adequate to explain the relationship between income inequality and health.

It is interesting to note that recent literature has studied the effect of income inequality on health status by capturing health measures beyond physical health; these include indicators such as teenage birth rates, obesity, crime and mental health (Layte 2012; Rufrancos et al. 2013; Wood et al. 2012; Pickett et al. 2006, 2005a, b). However, there is still a dearth of studies in the Indian context examining a similar research question mainly because of limited data availability. We will discuss two crucial evidence-based research papers in this context. Subramanian et al. (2007) examined the association between income inequality and the challenges of over and undernutrition in India using the National Family Health Survey data. They established an association between state income inequality and nutritional status, measured by the body mass index (BMI). In other words, a strong positive association is observed between the state-level Gini co-efficient and the risk of being underweight, overweight and obese. However, the study is limited to a sample of all women who are ever married in the age group of 15–49 years. Moreover, BMI may not be the only measure of nutritional status. It may not always be possible to capture the actual burden of chronic diseases and mortality through BMI.

Rajan et al. (2013) analyzed the effects of average income and income distribution on public health in India. They used the under-five and infant mortality rates at the district level along with self-reported health status as a health outcome. They found that infant mortality rates are negatively associated with average income levels and positively associated with poverty at the state as well as at the district level. However, income inequality is not associated with the infant or under-five mortality rates at the state or district level. In contrast, at the individual level, income inequality is a strong predictor of self-reported ailment. This critical study has a few limitations. First, it considered health status at the aggregate level to study the relationship between income and health. As we have already mentioned, such a relationship may not always infer causality between income (inequality) and health at the individual level. Secondly, self-reported health status, which has a positive relationship with income inequality, is subjective by nature. We may not get unbiased results using data on self-reported health status. Our study attempts to address these research gaps.

Data and Methodology

The objective of the paper is to analyze the association between income inequality and individual health status in India. We estimate the effects of state and district level income inequality on individual health status using the logit model. We attempt to disentangle the impact of individual income and income inequality simultaneously on individual health status by testing the income inequality hypothesis. The dependent variable is the health status of the individual. It takes the value one if the individual suffers from illness and zero otherwise.

We use the India Human Development Survey (IHDS) data, a nationally representative household survey, for analysis. The IHDS data covers 41,554 households, 33 Indian states and union territories, 1503 villages and 971 urban neighbourhoods across India. Two rounds of IHDS were conducted in 2004–05 and 2011–12. This dataset has a broad spectrum of information on individual health status, including short term morbidity, access to health care, and expenditure on health care. Both rounds have also collected data on household income along with details of the socio-economic characteristics of individuals.

We limit the analysis to the age group 14–74 years since the prevalence of short-term illness like diarrhoea and fever is more common among children and older adults.Footnote 1 Hence, the working sample size consists of approximately 293,494 individual observations. Appropriate weights are used for analysis. The descriptive statistics for all relevant variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

The Measure of Health Status

Unlike commonly used self-reported measures of health status, where people report whether they have poor or good health, we use short-term illnessFootnote 2 as a proxy measure of health status. IHDS I as well as IHDS II asked a series of questions on short-term illness from cough, fever and diarrhoea in the last thirty days before the survey.Footnote 3 Self-reported health status is subjective and may be influenced by other non-health factors. At the same time, the household response on ailments such as cough, fever or diarrhoea may be more reliable since these are easy to diagnose. We have created a binary variable of individual health status. The variable will take the value one if any individual suffered from at least one of the three short term illness mentioned above in the past thirty days; otherwise, it will take the value zero, thirteen per cent of the respondents within the specified age band suffered from short-term morbidity. We presented the weighted distribution of short-term morbidity across states in Fig. 1. The highest and lowest average proportion of short-term morbidity is experienced by Uttar Pradesh (19.26%) and Mizoram (0.22%).

Measures of Individual Explanatory Variables

To examine the impact of income inequality on health status using individual-level analysis, we have controlled for household-level income (as a proxy of individual income) and state or district level real income under all the specifications. We have also included household size along with household income. Individuals in the sample have an average annual household income of Rs 66,000. The monthly household income has been adjusted for inflation using the monthly consumer price index data. The mean household size is 5.86 for the panel while individual respondents are on an average 36 years old. The other individual-level co-variates include age, age square and indicator variables for sex, marital status, religion, caste and level of education.

Respondents are divided into two broad categories in terms of marital status – married and others. Three religion dummies—Hindu, Muslim, others (Christian, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain and Tribal) are included; Hindu is the base dummy. Scheduled caste, scheduled tribe, other backward caste and other caste are the major caste categories. The reference group is other backward caste for the caste variable. Seven education dummies—no education, below primary, primary, below secondary, secondary, higher secondary, graduate and above—are also included under all the specification of the econometric analysis where no education category is considered as the base dummy. Another crucial individual level co-variate is addiction. We considered smoking and alcohol consumption to capture it. A significant proportion of individuals admitted to alcohol consumption (8%) and smoking (22%).

An individual on an average spends Rs 556 for medical purposes. Medical cost comprises doctor’s fee, cost of medicine and travel cost to the doctor’s clinic or the health centre. The number of respondents reporting medical cost for short-term morbidity is low and, therefore, medical cost is not included in the econometric analysis. Although IHDS had asked whether an individual was covered by health insurance, we have excluded it from the analysis since the proportion saying yes is very low.

Measures of Income Inequality

We used the household-level income to estimate measures of income inequality at the state level. We construct four measures of income inequality for 29 major states for analysis. State mean income is calculated based on the number of observations per state using household-level weights. The number of state observations varies from 347 in Mizoram to 21,546 in Uttar Pradesh in the IHDS dataset. The first measure of income inequality is the co-efficient of variation (the standard deviation divided by the mean, expressed as a percentage) for household real income in each of the states. The inequality is also measured by the ratio of the 90th–10th percentiles of mean household income (Daly et al. 1998; Meara 1999; Vallore 2002) and the ratio of 50th–10th percentile of household income (Deaton 2001; Deaton and Paxon 2001). The fourth measure is the share of income going to the top 50% of the households (Vallore 2002; Meara 1999; Kaplan et al. 1996). We also have estimated similar measures of income inequality at the district level.

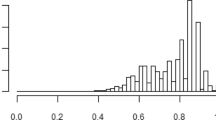

Descriptive statistics for state-level mean income and income inequality measures are reported in Table 2. The state-level annual mean income for the panel averages at Rs 56,429. The coefficient of variation (CV) averages 72.31 across states and between the two. We have presented the distribution of CV across states in Fig. 2. Mizoram (125.56) and Daman and Diu (55.66) observed the highest and lowest CV, respectively. The income inequality measure using the ratio of 90th–10th percentile has a mean of 10.84 with minimum and maximum at 3.65 and 36.86. Similarly, the ratio of 50th–10th percentile of income averages at 3.22 and ranges between 1.87 and 7.41. The fourth income inequality measure—the share of income going to the top 50% of the distribution has a mean of 0.87 while the minimum and maximum are 0.55 and 0.99, respectively. We have also presented the Pearson correlation coefficient between average state-level income and income inequality (Table 2). We find that although the correlation coefficient is statistically significant, the mean income is not highly correlated with the average of any of the four income inequality measures.

Methodology

We used a logit model to estimate the impact of income inequalities on individual health status.

The regression equation outlining the relation among individual health outcomes, individual income and income inequality at the state/district (societal) level may be expressed as follows:

where Yij is the health status of individual i in state j; xij is the income of individual i in state j (where β* estimates the relation between Yij and xij within a society); wj is the level of income inequality in state j (∞ estimates the effect of societal income inequality on individual health) taking into account the individual income-health relationship. uj is the residual difference in societal health after accounting for income inequality at the state level, while eij is the residual difference in individual health after accounting for individual income. We used multilevel regression model instead of standard regression or fixed, or random effect model since it (Eq. 1) can capture the variation coming from two sources – individual (eij) and state (society) (uj). To capture both the effects simultaneously, it is important to include individual income as well as income inequality at the societal level as explanatory variables.

For our analysis, we used a modified version of Eq. (1), which is given below:

where the subscript t indicates time. Therefore, Yijt, xijt and wjt become the health status of individual i in state j in time t, the income of individual i in state j in time t and the level of income inequality in state j in time t respectively. Aijt is the matrix of control variables at the individual level. It includes household size, age, age square, gender, marital status, religion, caste and level of education. Dt and Dj are the time and state dummy, respectively. We discussed all the explanatory variables in detail in the data section.

The dependent variable takes the value one if an individual suffers from poor health and zero otherwise. We have tested both the strong and the weak “income inequality hypothesis (IIH)” in the Indian context. To test the strong IIH, we have estimated the impact of income inequality on the health status of all individuals after including household-level income, the individual co-variates mentioned above, state and year fixed effect. We used all the four income inequality measures to check the robustness of the results. For space limitation, we have reported the regression result of CV and the ratio of 90th–10th percentile of strong IIH in Tables 3 and 4 and weak IIH in Tables 5 and 6.Footnote 4 While we reported the results using the 50th–10th percentile and share of income going to the top 50% of the distribution in the appendix (Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10) in ESM.

The estimated effects of mean income and state-level income inequalities from the logit model on individual health status are reported in those tables. To capture the concavity-led income inequality effect as discussed under theoretical foundation, we controlled for a non-linear spline approximation of household income. The spline function helps us to fit a piecewise linear regression model instead of a simple linear regression model. The knots of the splines are defined at the quintiles of the income distribution. The sign and statistical significance of five household income splines indicate the impact of five income categories on individual health status.

To check for the robustness of the estimates, we also have carried out a district-level analysis for four income inequality measures. The marginal effects under each specification are reported. Standard errors are calculated based on robust variance estimates.

Results and Discussion

The effect of income inequality on the probability of ill health using the four measures of income inequality is positive and significant, although the magnitude of the impact varies. Further, the effect remains positive under all the specifications, even when we control for individual and state-specific characteristics.Footnote 5

Below, we describe the results when the ratio of the 90th–10th percentile of income distribution at the state level is used as a measure of income inequality (Table 4). We find that the average marginal effect of income inequality is 0.0321 when we do not control for individual characteristics or mean income. The magnitude of the marginal effect decreases as we include state-specific characteristics, household-level income and individual-level characteristics as control variables in Model 2.

The result is robust with the addition of the non-linear effect of household income along with the other individual co-variates, such as age, age square, sex, marital status, religion, caste, education, urban dummy and two addiction variables—smoking and alcohol consumption; in Model 3. In other words, the effect of income inequality on the probability of short-term morbidity remains significant, but the magnitude of such effect decreases with the inclusion of splines of household income in the regression specification. It holds for each of the income inequality measures used for analysis except the share of top 50% income distribution.

The impact of household income on health status is negative and significant under all the specifications when it is linear (Model 2). The marginal effects of income splines (Model 3) taking care of the non-linear effect of household income are negative and significant for the poorest and middle-income groups in the distribution. The individual income co-efficient for the splines of the two high-income groups are also found to be statistically insignificant.

Some of the individual characteristics included in the models also play an interesting role.Footnote 6 The probability of falling ill is consistently higher for women under all the specifications—the probability of falling sick increases with increase in age. People living in urban areas are less prone to diseases compared to their rural counterparts. Respondents from scheduled caste are 5% more likely to fall ill when income inequality is measured as the ratio of the 90th–10th percentile of income. Considering the result of same income inequality measure, in 27% of the cases, higher educated people, specifically, those who have completed graduation or post-graduation degree, are less likely to suffer from ill-health compared to illiterate respondents. The probability of morbidity is 23% higher for smokers. However, alcohol consumption did not have any significant effect on morbidity. Although the magnitude of these co-efficient varies across different income inequality measures, the sign and level of significance remain almost the same.

Other important determinants of health status are access to medical care, the expenditure incurred for medical care, medical insurance, quality of medical care and several environmental and behavioural factors. Although we have information on some of these determinants, it is limited. Therefore, we were not able to include such determinants explicitly for analysis.

In summary, we found that income inequality is in general bad for the health of all people in a country, i.e., the strong version of the IIH applies in the Indian context even when the inclusion of individual characteristics and non-linear individual income leads to variation in the magnitude of the effect.

We then examine whether income inequality affects people across different income strata equally by testing for the weak version of the IIH. The procedure is similar to testing the strong version of IIH except that we will estimate the effect of household-level income inequality instead of state-level income inequality. To address this, we constructed five household income dummy variables based on the quintile distribution of household income. If an individual is a member of a household whose income lies at the 35th percentile of the income distribution, a categorical variable will take the value 1 for the second-lowest income category, and four dummies for the other quantiles will be set equal to zero. Then, these dummies are interacted with the respective measure of income inequality at the state/ district level. This enables us to estimate how income inequality affects low-income individuals compared to high-income ones through the signs and magnitudes of the co-efficient of the interaction terms.

We have reported the results in Tables 5 and 6 in the manuscript and Tables 9 and 10 in the appendix in ESM. Like the previous estimation for strong IIH, we have analyzed for each of the four income inequality measures—co-efficient of variation, the ratio of 90th–10th percentile of income, the ratio of 50th–10th percentile of income and income share of top 50%. We have controlled for individual co-variates, and state-level characteristics, including state fixed effect. An estimation has been carried out for the state level as well as district-level income inequality. Robust standard errors are reported along with the marginal effects.Footnote 7

Marginal effects of each of the four income inequality measures are positive and significant as observed from the tables above. Interestingly, we found that the interaction term between the income inequality measure and household income dummies for two high-income groups are negative and statistically significant. This indicates that the health of individuals from the poorer sections is more sensitive to income inequality compared to the rich.

We will describe the results from Table 5, where the effect of the coefficient of variation (CV), the measure of income inequality, along with the effect of an interaction term between household income terms and CV is measured on individual health status. It is evident from Model 1 that, without controlling for individual-level characteristics, state-level income inequality has varying impact on individual health status across different income strata. The likelihood of falling ill is low for middle-income households compared to the poor and even lower for the highest income group as compared to the poorest income group. When we control for individual characteristics, the effect strengthens further, establishing the weak IIH—poor income group suffers more due to income inequality (Model 2). We have controlled for regional variation through state fixed effect. The results are similar for all the four income inequality measures. The regression estimates with all four income inequality measures at the state and district level indicate that individuals from poor income groups are more affected by income inequality in terms of individual health status.

We find similar effects of relevant individual characteristics as observed in testing the strong IIH. Women are more likely to fall ill even when we test for weak IIH. Education plays an important role as a determinant of individual health. Higher education leads to a lower probability of falling ill.Footnote 8 Smoking increases the likelihood of adverse health for individuals while we did not find any significant impact of alcohol consumption on health.

We found out similar results of IIH at the district level through estimation of the four-district level income inequality measures. We also checked the robustness of the fitted models by estimating the R-square and model chi-square. Model chi-square is statistically significant for all the four income-inequality measure analysis under each of the three different specifications. R square improved from Model 1 to Model 3, indicating a better fit.

Conclusion

We examined the relationship between income inequality at the state and district level and individual health status (short term morbidity) in India by considering the non-linear effect of individual income, relevant individual co-variates and regional diversity. Our study will be an important value addition in relevant literature since there are very few research papers that address a similar research question in the Indian context due to data limitations. We used a large sample inclusive of men and women instead of using only all women sample (Kawachi and Smith 2007) for analysis. Short term morbidity used as a proxy of individual health status in our paper is a more robust measure of individual health status compared to the health measures used in the existing Indian literature like BMI of women (Kawachi and Smith 2007) or under five and infant mortality rate or self-reported health status (Rajan et al. 2013).

Under all the specifications, with or without controlling for individual characteristics and using different income inequality measures, we concluded that income inequality increases the probability of short-term morbidity. In other words, income inequality is associated with adverse health.

We found that a higher level of income inequality leads to bad individual health for all individuals in society in general without controlling for any other factor. The magnitude of the effect varies when we control for individual income along with other related individual co-variates. Such control variables were used to take care of the omitted variable bias. We controlled further the non-linear effect of individual income through income splines. The relationship between income inequality and the likelihood of bad individual health remains positive and significant. We controlled for regional diversity effect through state fixed effects in all the different models tested.

Although the magnitude of the income inequality effect on the probability of short-term morbidity varies across different models, the effect is consistently positive and significant; the higher the level of income inequality, the higher is the probability of falling ill in the short run. Besides, the intensity of the income inequality effect varies across different income groups. People in the poorest income group are the worst sufferers.

The evidence regarding the negative impact of income inequality on health requires immediate public policy attention. Even though richer is healthier, the focus would not only be on increasing average level of income of the country. It is essential to emphasize reducing income inequality through increasing effectiveness for poverty alleviation programs. For example, wages or provision of the maximum number of days work can be increased under Mahatma Gandhi Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), one of the recent flagship poverty alleviation program launched by Government of India in 2005. Options of livelihood in a farm as well as non-farm activities may be expanded under National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM), so that rural women get better economic opportunities. More focus is needed for improving the quality of education and skill development program for rural youth in India. National Skill Development Mission may be more proactive in building market linkages for local level entrepreneurs. In addition to poverty alleviation measures, public health policy also needs to be strengthened in terms of improvement in health infrastructure, availability of qualified human resources, uninterrupted supply of essential drugs, availability of pathological testing facilities in the primary and community health care centres, etc. Coordination among different government departments dealing with social protection schemes will be helpful to improve the scenario.

Notes

We excluded children and elderly people from analysis to avoid selection bias.

We did not consider long term morbidity since many of the long-term diseases are chronic. And it would be difficult to study the impact of income inequality on long term morbidity (under ceteris paribus condition) because of chronic nature of such diseases.

These are the only three illness variables reported in IHDS for short term morbidity which can be considered as the limitation of the study.

We estimated four income inequality measures for robustness check. All four income inequality measures ideally provide similar results. For space limitation, we have reported results for CV and the ratio of 90th to 10th percentile in the main paper. While we reported the results of the rest two in the appendix (Tables 7 and 8) in ESM.

The assumptions of multilevel regression are same as their single level counterparts (Hox 2013) i.e. logistic regressions (as used in this research paper). We validated the major assumptions of the logistic regression including multicollinearity and appropriate specification of the model. There is no multicollinearity or mis-specification of the model under most of the model specifications used.

Detail results for the individual explanatory variables under all the model specifications could not be presented due to space limitation. It will be available upon request.

We checked for inter cluster correlation at the state level which signifies that the observations within cluster are somewhat similar. To address this, we carried out regression analysis under different model specifications with cluster level standard errors (including state/ district level income inequalities after controlling for state level characteristics including state dummies and state real income). The result remains robust.

Education and individual health status may have a two-way causality. Education may lead to better health. On the contrary, healthy people may have better education. To check the robustness of the result, we carried out the estimation analysis after excluding education variable as one of the explanatory variables. All the results remain robust with expected sign and statistical significance of main variable of interests.

References

Daly, M.C., G.J. Duncan, and G.A.W.L. KaplanJohn. 1998. Macro-to-micro links in the relation between income inequality and mortality. The Milbank Quarterly 76 (3): 315–339.

Daly, M., M. Wilson, and S. Vasdev. 2001. Income inequality and homicide rates in Canada and the United States. Canadian Journal of Criminology 43 (2): 219–236.

De Vogli, R., R. Mistry, R. Gnesotto, and G.A. Cornia. 2005. Has the relation between income inequality and life expectancy disappeared? Evidence from Italy and top industrialized countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 (2): 158–162.

Deaton, A. 2001. Inequalities in Income and Inequalities in Health" in The Causes and Consequences of Increasing Inequality, ed. Finis Welch, 285–313. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Deaton, A, and Paxson, C, 2001. Mortality, Education, income and inequality among American cohorts. Themes in the Economics of Aging, ed. David Wise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Hox, J. J. 2013. Multilevel regression and multilevel structural equation modeling. In Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods: Statistical analysis, ed. Little TD, 281–294. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaplan, G.A., R.P. Elsie, J.M. Lynch, D.C. Richard, and L.B. Jennifer. 1996. Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. British Medical Journal 312 (7037): 999–1003.

Kawachi, I. 2000. Income inequality and health. In Social epidemiology, ed. L.F. Berkman and I. Kawachi, 76–94. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kawachi, I., P.K. Bruce, K. Lochner, and D. Prothrow-Stith. 1997. Social capital, income inequality and mortality. American Journal of Public Health 87 (9): 1491–1498.

Kondo, N., I. Kawachi, S.V. Subramanian, Y. Takeda, and Z. Yamagata. 2008. Do social comparisons explain the association between income inequality and health?: Relative deprivation and perceived health among male and female Japanese individuals. Social Science and Medicine 67 (6): 982–987.

Layte, R. 2012. The association between income inequality and mental health: testing status anxiety, social capital, and neo-materialist explanations. European Sociological Review. 28 (4): 498–511.

Lynch, J.W., G.D. Smith, G.A. Kaplan, and J.S. House. 2000. Income inequality and mortality: Importance to health of individual income, psychological environment or material conditions. British Medical Journal 320 (7243): 1200–1204.

Marmot, M. 2002. The influence of income on health: Views of an epidemiologist. Does money really matter? Or is it a marker for something else? Health Affairs Millwood 21 (2): 31–46.

Meara, E. 1999. Inequality and infant health. Cambridge: Harvard University.

Mellor, J.M., and J. Milyo. 2002. Income inequality and health status in the United States: Evidence from the current population survey. The Journal of Human Resources 37 (3): 510–539.

Murali, V., and F. Oyebode. 2004. Poverty, social inequality and mental health. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 10 (3): 216–224.

Pickett, K.E., S. Kelly, E. Brunner, T. Lobstein, and R.G. Wilkinson. 2005. Wider income gaps, wider waistbands? An ecological study of obesity and income inequality. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 59 (8): 670–674.

Pickett, K.E., J. Mookherjee, and R.G. Wilkinson. 2005. Adolescent birth rates, total homicides, and income inequality in rich countries. American Journal of Public Health 95 (7): 1181–1183.

Pickett, K.E., O.W. James, and R.G. Wilkinson. 2006. Income inequality and the prevalence of mental illness: a preliminary international analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 60 (7): 646–647.

Rajan, K., J. Kennedy, and L. King. 2013. Is wealthier always healthier in poor countries. The health implications of income, inequality, poverty, and literacy in India. Social Science and Medicine 88: 98–107.

Rasella, D., R. Aquino, and M.L. Barreto. 2013. Impact of income inequality on life expectancy in a highly unequal developing country: the case of Brazil. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 67 (8): 661–666.

Rodgers, G.B. 1979. Income and inequality as determinants of mortality: An international cross-section analysis. Population Studies 33 (2): 343–351.

Ross, N.A., M.C. Wolfson, J.R. Dunn, J.-M. Berthelot, G.A. Kaplan, and J.W. Lynch. 2000. Relationship between income inequality and mortality in Canada and in the United States: Cross-sectional assessment using census data and vital statistics. British Medical Journal 320 (7239): 898–902.

Rufrancos, H., M. Power, K.E. Pickett, and R. Wilkinson. 2013. Income inequality and crime: A review and explanation of the time-series evidence. Social Criminology 1: 103.

Subramanian, S.V., and I. Kawachi. 2004. Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiologic Reviews 26 (1): 78–91.

Subramanian, S.V., I. Delgado, L. Jadue, J. Vega, and I. Kawachi. 2003. Income inequality and health: multilevel analysis of Chilean communities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57 (11): 844–848.

Subramanian, S.V., I. Kawachi, and D.J. Smith. 2007. Income inequality and the double burden of under- and over nutrition in India. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 61: 802–809.

Wagstaff, A., and D.E. Van. 2000. Income inequality and health: what does the literature tell us? Annual Review of Public Health 21: 543–567.

Waldmann, R.J. 1992. Income distribution and infant mortality. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (4): 1283–1302.

Wilkinson, R.G. 1992. Income distribution and life expectancy. British Medical Journal 304 (6820): 165–168.

Wilkinson, R.G. 1996. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. London, New York: Routledge.

Wood, A.M., C.J. Boyce, S.C. Moore, and G.D. Brown. 2012. An evolutionary-based social rank explanation of why low income predicts mental distress: A 17-year cohort study of 30,000 people. Journal of Affective Disorders 136 (3): 882–888.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to the participants and discussant of the third Annual IHDS User Conference, 2016 and two anonymous referees, for their valuable comments.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Paul, S. Income Inequality and Individual Health Status: Evidence from India. J. Quant. Econ. 19, 269–289 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-020-00223-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40953-020-00223-x