Abstract

Emotional intelligence, which encompasses the ability to perceive, understand, express, and regulate emotions, is recognized as critical to the socioemotional development of adolescents. Despite its significance, the relationship between emotional intelligence and social media use among adolescents remains largely unexplored in the literature. This work aimed to provide a review that examines the association between adolescents’ emotional intelligence, including its dimensions (self-esteem, emotion regulation, empathy), and social media use. An online search of two electronic databases identified 25 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The results suggest that lower levels of emotional intelligence are associated with increased problematic social media use among adolescents, with social media use showing a negative correlation with adolescents’ self-esteem. In addition, difficulties in emotion regulation were associated with problematic social media use, while social media use was positively correlated with empathy. These findings underscore the importance of considering emotional intelligence as a key factor in understanding the relationship between adolescents and problematic social media use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study examines the relationship between emotional intelligence, emotional regulation, self-esteem, empathy, and social media use among adolescents. Social media platforms have become a crucial aspect of adolescents' daily lives, significantly influencing their behavior, communication patterns, and self-presentation. Due to its potential implications for adolescents' social and emotional development, understanding the impact of emotional intelligence on adolescents' social media use is of significant importance. Although systematic reviews have examined the relationship between problematic technology use, including problematic Internet use and Internet gaming disorder, and emotional intelligence, (Gisbert-Pérez et al., 2024; Leite et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022), no review has focused specifically on the correlation between social media use and emotional intelligence. The purpose of this study is to address this gap by conducting a systematic review of the relationship between emotional intelligence and social media use in adolescents.

Social Media Use During Adolescence

In the current digital age, social media has taken on a dominant role among adolescents. Social media experience has cognitive, emotional, behavioral and social dimensions (Ferrara & Yang, 2015; Korte, 2020). The digital environment provides a compelling context for youth to navigate socio-developmental tasks with a significant impact on their social-emotional well-being (Valkenburg, P. & Peter, J, 2013). As peer bonding is a key developmental task during adolescence, it is not surprising that social media and social network platforms are attractive to adolescents. Indeed, the most recent global census data indicate that Generation Z consisting of individuals born from the mid-1990s to the early 2010s, holds the title for the most extensive usage of social media, averaging over 2.5 h daily on these platforms (Global Web Index, 2023). Furthermore, 71% of adolescents access more than one platform and nearly a quarter admit to being online all the time due to increased mobile accessibility via smartphones (Schivinski et al., 2020). However, concerns about problematic and addictive adolescent social media use are emerging. Research suggests that time spent on social media daily is a risk factor for developing dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use (Schivinski et al., 2020). According to experts, problematic social media use resembles addiction with associated compulsivity, tolerance, withdrawal, motivation, and dysfunction (Shafi et al., 2021). Adolescents with problematic social media use typically have a diminished ability to regulate their social media use impulses and feel uncomfortable when social media use is restricted (Boer et al., 2020). A large-scale study of European adolescents found that the prevalence of addiction-like problematic social media use was 9.1% (Mérelle et al., 2017).

Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence, defined by Salovey and Mayers (1990), as the ability to perceive, understand, express, and regulate emotions, plays a key role in promoting social adjustment and psychological well-being, especially during adolescence. Emotional intelligence is divided into different conceptualizations: ability emotional intelligence and mixed-model emotional intelligence. The Ability-based model originates from the groundbreaking research conducted by Salovey and Mayer. They formulated a four-branch model of emotional intelligence, encompassing skills such as perception, appraisal, and expression of emotion; using emotions to enhance cognitive processes, understanding and analyzing emotions, using emotional knowledge; and adaptive regulation of emotion (Salovey et al., 1999). Mixed models characterize emotional intelligence as a collection of interrelated emotional and social competencies, skills and facilitators that determine how effectively individuals understand and express themselves, understand others and relate with them, and cope with daily demands (Bar-On, 1997). Another differentiation was further operated by Petrides and Furnham (2001), who distinguished Trait emotional intelligence (TEI) from Ability emotional intelligence (AEI) and claimed that the nature of the model is determined by the type of measurement. Trait emotional intelligence is defined as a constellation of emotional self-perceptions located at the lower levels of personality hierarchies and measured via the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEI-Que), while Ability emotional intelligence concerns emotion-related cognitive abilities that ought to be measured via maximum-performance tests (Petrides et al., 2007). However, the different “definitions’’ of emotional intelligence tend to be complementary rather than contradictory (Ciarrochi et al., 2000). According to Petrides and Furnahm (2001), Trait emotional intelligence includes various personality traits such as empathy and assertiveness (Goleman, 2005), as well as elements of social intelligence (Thorndike, 1920), personal intelligence (Gardner, H, 1983), and ability emotional intelligence (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). The domain of Trait emotional intelligence includes 15 distinct components: trait optimism, trait happiness, self-esteem, emotion management, assertiveness, social awareness, empathy, emotion perception, emotion expression, relationships, emotion regulation, impulsiveness (low), stress management, self-motivation, and adaptability. Hughes and Evans (2018) identified several limitations in existing models of emotional intelligence, including the lack of clear and concise definitions that provide boundaries for each emotional intelligence-related construct and the absence of a theoretical framework. To overcome these limitations, they proposed an integrative theoretical model, which includes ability emotional intelligence, affect-related personality traits, and emotional regulation, called the Integrated Model of Affect-related Individual Differences.

Emotional Intelligence in Adolescence

Despite differences among emotional intelligence models, their application has resulted in numerous emotional intelligence-related findings, such as correlations between higher emotional intelligence scores and well-being, prosocial behavior, and physical activity (Laborde et al., 2016; Llamas‐Díaz et al., 2022; Mavroveli et al., 2009; Sanchez-Alvarez et al., 2015). During adolescence, emotional intelligence is particularly relevant, as it affects the quality of relationships with peers, family, and teachers (Petrides et al., 2006). Adolescents with high emotional competencies tend to have some relationship skills, such as the ability to both communicate and listen clearly and to manage conflict constructively, which can help them maintain interpersonal relationships (Wang et al., 2019). Research suggests that emotional intelligence is an important construct in preventing health and behavioral problems, including problematic Internet and technology use (Sural et al., 2019). In fact, several studies indicate that higher emotional intelligence correlates with more adaptive coping and fewer dysfunctional strategies (Alshakhsi et al., 2022; Kun & Demetrovics, 2010). On the other hand, people with lower levels of emotional intelligence are more likely to develop problematic behaviors. A small number of studies have shown that lower levels of emotional intelligence may be correlated with higher levels of problematic use of technological communication media such as smartphones, the Internet, and video games (Alshakhsi et al., 2022; Che et al., 2017; Gisbert-Pérez et al., 2024). A recent review found a positive correlation between adolescent emotion dysregulation and the severity of problematic technology use, including problematic smartphone use, problematic Internet use and Internet Gaming Disorder (Yang et al., 2022). Nonetheless, there is still relatively limited research examining the relationship between emotional intelligence components and these problematic behaviors.

Current Study

Emerging evidence suggests that emotional intelligence may act as a protective factor against various negative outcomes, including problematic technology use. However, its specific relationship with social media use remains underexplored, particularly within the context of adolescence. To address this gap, the current study systematically reviewed the literature on emotional intelligence and social media use during adolescence. defined as the period between the ages of 10 and 19.

Methods

Information Sources and Search Terms for Identification of Studies

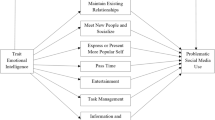

Between January 2023 and August 2023, an exhaustive search was conducted using the Web of Science Core Collection and Pubmed electronic database using the search strings stated in Table 1. The search query was formulated to identify studies investigating the nexus between emotional intelligence and social media among adolescents’ group. Given the relative scarcity of research focusing on the interplay between emotional intelligence and social media utilization among adolescents, specific facets within the framework of Trait emotional intelligence, were included in the search string. According to Petrides and Furnham (2001), the sampling domain of Trait emotional intelligence includes four primary factors (Well-Being, Self-Control, Emotionality, and Sociability) and a total of 15 facets. For each of these primary factors, one specific facet was selected (emotional regulation, emotion management self-esteem and empathy). To include studies that have not emerged from the initial databases-research, reference lists from previously identified articles were also screened as a source of information.

Screening (Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria)

The second phase of the review process entailed a screening procedure conducted in adherence to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion criteria for the search strategy were articles published in English and Spanish, peer-reviewed journals, between the years 2001 and 2023. The decision to limit the study to this specific period was motivated by the notable development of social media, coinciding with the introduction of tools for assessing emotional intelligence in 2001, e.g. Ciarrochi et al., (2001). To be considered for inclusion, studies were required to utilize instruments or methodologies grounded in one of the various established theoretical models of emotional intelligence or Trait emotional intelligence or one of its facets. Moreover, the selection criteria extended to studies that investigated both the overall extent of social media usage and the specific types of usage. This approach allowed for a comprehensive examination of the influence of social media on emotional intelligence across various dimensions. The WHO (2015) defines adolescence as the period between the ages of 10 and 19 years, so the participants' age range had to be from 10 to 19 years, including individuals of any ethnicity or gender. Articles that included participants recruited from college or postsecondary education settings were also subject to exclusion, because such studies expanded the age range beyond the confines of adolescence, and they did not offer separate analyses of results based on age groups. Cross-sectional or longitudinal designs, and only full-text articles were included. Including specific facets provides a detailed understanding of how emotional intelligence interacts with adolescents' behavior on social media platforms.

Abstracts, reports, duplicates, conceptual papers, research debates, commentaries and book reviews were excluded. To maintain the focus of our analysis, articles featuring clinical samples were deliberately excluded. The primary aim was to investigate the connection between emotional intelligence and social media usage from a preventive standpoint, to draw conclusions that possess reduced potential for bias. Furthermore, the selection process involved the exclusion of studies that examined emotional intelligence and social media usage but did not explicitly investigate the relationship between these two constructs. This approach ensured the inclusion of studies that directly contributed to the objective of scrutinizing the interplay between emotional intelligence and social media use among adolescents, thus enhancing the robustness of the conclusions”.

Eligibility

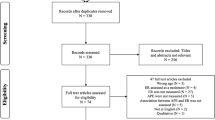

Eligibility is the process by which the author manually includes or excludes literature items in light of particular criteria in accordance with the research question and the study objectives (Tang et al., 2021). An examination was conducted on all the retrieved articles, and only those aligning perfectly with the predefined criteria were considered suitable for inclusion. Titles and abstracts of all retrieved publications were imported into Zotero, and duplicates were removed by one reviewer. Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts of retrieved articles. Articles that were deemed highly unlikely to be relevant based on their title and abstract were disregarded. Full-text versions of the remaining articles were then obtained and screened independently by the same reviewers. Researchers were blinded to each other's decisions throughout the selection process. Disagreements between the reviewers’ decisions were resolved through discussion. Following the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the subsequent manual screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts, a total of 25 articles met the stringent standards and were retained for the synthesis. Full-text versions of the remaining articles were screened independently by the same reviewers. The results of the literature search and the subsequent selection process are visually depicted in the flowchart provided in Fig. 1. The included studies were categorized according to different components and dimensions of emotional intelligence to facilitate a comprehensive analysis of their contributions to the research objectives. One additional study was identified after screening the reference lists of eligible articles.

Quality Assessment, Data Extraction and Synthesis

The quality of the studies reported was assessed using the Observation Study Quality Evaluation tool (OSQE) (Drukker et al., 2021). The OSQE has a cohort version, a case–control version and a cross-sectional version. All three versions have a different scoring system. The OSQE cross-sectional is a selection of items from the OSQE cohort. The OSQE cohort includes 14 obligatory items and 2 optional items, while the OSQE cross-sectional includes 7 obligatory items and 3 optional items (a higher score represents a better quality). Quality assessment of the selected studies was performed by two authors independently and, through meetings, consensus was reached on the score of the articles (refer to Supplementary Material for scoring details). For each of the selected articles, a data extraction process was undertaken, encompassing multiple essential facets. This included parameters such as the identification of authors, the year of publication, sample size, mean age of subjects, gender distribution, geographical origin of the research, specific instruments used for the assessment of emotional intelligence, self-esteem, empathy, emotional regulation, the extent of involvement with social media platforms, and the primary outcomes derived from the investigation (Table 2). Due to the heterogeneity of studies (different measures, different approaches, and designs), the articles that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria were synthesized using a qualitative narrative approach. The description of the data and findings from the systematic review was the basis for the qualitative synthesis.

Results

Study Characteristics

Twenty-five articles meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in this review. The total number of participants across the 25 articles was 41.624 (boys’ percentage across studies = 49.3%; mean age across studies = 14.6 years). In all the studies, data were collected through questionnaires. Twenty studies used a cross-sectional perspective, while four studies used a longitudinal methodology. The distribution of the nationalities was: Spain (5), Netherlands (3 Turkey (3), Italy (2), Australia (2), Iceland, United States (2), United Kingdom, Germany, Belgium, China, and Scotland (one study each). Most of the excluded studies did not report the association between emotional intelligence and social media use or involved participants outside the age range of 10–19 years old or did not contain at least one component of emotional intelligence or social media use. Based on OSQE cross-sectional scores, 31.6% (n = 6), 26.3% (n = 5), 26.3% (n = 5), 10.6% (n = 2) and 5.3% (n = 1) were rated 5, 6, 8 and 2 stars out of 10, respectively. Based on the OSQE cohort scores, 66.7% (n = 4), 16.7% (n = 1) and 16.7% (n = 2) were rated 9, 10 and 7 stars out of 16 respectively.

Emotional Intelligence and Social Media in Adolescents

The literature review showed four relevant results regarding the construct of emotional intelligence about social media. All studies examined social media use from a problematic standpoint, with three utilizing the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (BSMAS) and the remaining one employing the Social Media Addiction Questionnaire (SMAQ) (Andreassen et al., 2017; Hawi & Samaha, 2017). The BSMAS assesses with 6 items the characteristic symptoms of addiction (i.e., salience, conflict, mood modification, withdrawal, tolerance, and relapse), without making a diagnosis of addiction, but suggesting a level of risk of problematic social media use. The SMAQ is composed of eight items scored on a 7-point Likert scale that ranges from strongly disagree strongly agree, with higher scores indicating dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use. Two of the studies measured emotional intelligence using the Wong and Law's Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) (Law et al., 2004), while two used the TEI-QueSF (Petrides, 2009). The WLEIS is often used to measure a range of basic emotional skills and consists of a 16-item scale divided into four subscales: self-evaluation of emotions, evaluation of others' emotions, use of emotions, and regulation of emotions. The TEI-Que comprises fifteen emotional intelligence domain personality grouped into four dimensions: well-being, self-control, emotionality and sociability. Two of these studies were conducted in Spain, one in Turkey and one in Italy. All the studies included in this review highlight a negative relationship between emotional intelligence and dysfunctional social media use In the majority of studies (Arrivillaga et al., 2022b; Kircaburun, et al., 2019; Pino & Mastromarino, 2023), gender differences in problematic social media use were observed and were significantly higher in females compared to males; conversely, males tended to have higher levels of emotional intelligence. The correlational analyses of the Kirkaburun (2019) and Arrivillaga (2022a) study show a significant negative association between dysfunctional mechanisms of social media use and emotional intelligence, while the Arrillaga (2022b) study shows a negative and significant association only in the female sample. Several specific mediating variables were examined in these studies. It was found that perceived stress acts as a mediator in the relationship between emotional intelligence and problematic social media use, while depressive symptoms play a partial mediating role in this relationship (Arrivillaga et al., 2022a). Mediational analysis results showed that mindfulness, rumination and depression fully accounted for the association between trait emotional intelligence and problematic social media use (Kircaburun, et al., 2019) Consistent with Pino and Mastromarino's (2023) findings, increased stress and decreased emotional intelligence emerged as predictive factors associated with an increased likelihood of developing social network addiction. It should be noted, however, that the studies are not without limitations. One such limitation relates to the use of self-report measures for both problematic social media use and emotional intelligence, which may be susceptible to the influence of social desirability bias. In addition, the research designs adopted a cross-sectional approach, which precludes the establishment of causal relationships between the variables under investigation.

Adolescents’ Self-Esteem and Social Media Use

Constant exposure to social media encourages users to compare themselves to others online, which can be detrimental to their self-esteem (Alfasi, 2019). This effect is notably significant during adolescence, a developmental stage where individuals shape their identities and evaluate themselves based on both internal and external perceptions (Acar et al., 2022). There is a relatively large body of research that has examined the association between social networking site use and self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is the most commonly used survey measure to assess general, trait-like levels of self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1989). According to Rosenberg, self-esteem manifests when ‘‘a specific object (in this case, oneself) holds a positive or negative attitude with essentially the same qualities and attitudes as towards other objects (besides oneself)’’ Consequently, he posited that, given the measurability of attitudes towards objects, attitudes towards oneself could similarly be quantified. The self-esteem scale developed by Rosenberg consists of 10 items, with responses assessed on a Likert scale. The majority (11) of studies on SOCIAL MEDIA USE and self-esteem in this review used Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale (Acar et al., 2022; Ciacchini et al., 2023; Cingel & Olsen, 2018; Errasti et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2018; Livet et al., 2022; Martinez-Pecino & Garcia-Gavilán, 2019; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Valkenburg, Beyens, Pouwels, Van Driel, et al., 2021; Woods & Scott, 2016; Xu et al., 2023). However, two studies (Rodgers et al., 2020; Valkenburg, Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, et al., 2021), employed a single-item measure of self-esteem (“How satisfied do you feel about your-self right now?”; “I have high self-esteem”). The key finding was a weak-to-moderate correlation between social media use and lower self-esteem. The assessment of variables related to social media has emerged as a more diversified research field, with numerous research tools being employed to examine various dimensions of engagement and problematic usage. Some studies have focused on the problematic aspect of social media usage, utilizing targeted instruments to measure this phenomenon (Acar et al., 2022; Ciacchini et al., 2023; Martinez-Pecino & Garcia-Gavilán, 2019; Xu et al., 2023). These tools include the Problematic Instagram Use (Marino et al., 2017), the Social Media Addiction Scale (Sahin, C., 2018), the Mobile Social Addiction Scale (Liu et al., 2023) and the BSMAS (Monacis et al., 2017). A study examining the relationship between problematic Instagram use and the number of likes received on posts found a notable correlation with self-esteem. Specifically, it identified a negative direct effect of self-esteem on problematic Instagram use, indicating that individuals with higher self-esteem tend to exhibit lower levels of problematic Instagram use (Martinez-Pecino & Garcia-Gavilán, 2019). A consistent pattern of negative correlations has been found in the research carried out by other studies on addiction to social media and self-esteem (Acar et al., 2022; Ciacchini et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2023). These findings suggest that individuals with lower self-esteem may be more susceptible to developing an addiction to social media platforms. For these individuals, social media may potentially serve as a means of seeking validation and building social connections.

Studies on social media use duration among adolescents often involve custom questions to assess this aspect, for example, ‘‘On average, how many hours a day do you spend on social media ?’’ or ‘‘How much time a day do you spend on Facebook, Twitter or other social media?’’.

It is important to underline that the findings of such studies are based on participants' estimates and subjective perceptions of their social media behavior, so there may variations and limitations related to participants' memory or perception of time (Lee et al., 2021). All studies included in this review found significant weak to moderate negative associations between time of social media use and self-esteem (Ciacchini et al., 2023; Cingel & Olsen, 2018; Kelly et al., 2018; Livet et al., 2022; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Valkenburg, Beyens, Pouwels, van Driel, et al., 2021). A negative correlation was found between usage time and self-esteem (r = -0.188, p < 0.001), and a slight negative correlation between active and passive social media use was also noted in a study (Thorisdottir et al., 2019).

Focused on two prominent social networking platforms, Facebook and Twitter, the ‘Facebook Use Questionnaire’ and the ‘Twitter Use Questionnaire’ were developed to provide detailed insights into users’ posting frequency, updates, expression of personal emotions, and empathy towards others’ emotions. Findings highlighted a significant negative relationship between self-esteem and the frequency of Facebook use (r = -0.124; p = < 0.05). Similarly, self-esteem exhibited a significant negative correlation with both the frequency of Twitter use and the expression of emotions on Twitter (r = -0.151; p < 0.01; r = -0.187 p < 0.01).

Two studies incorporated in this review adopted a longitudinal methodology. In Valkenburg and colleagues study ( 2021), levels of social media use and self-esteem were assessed by an average of 126 momentary assessments of both variables over three weeks. Analyses revealed a significant negative association between Instagram, Snapchat and WhatsApp use and participants’ self-esteem, meaning that participants who spent more time on social media over the three weeks had lower average self-esteem than those who spent less time on social media over this period. In contrast, Livet’s study (2022) extended over five years, during which participants consistently responded to annual surveys at twelve-month intervals. The findings indicated noteworthy associations between social media and self-esteem across these five time points. Specifically, adolescents with higher levels of social media use and video gaming reported consistently lower self-esteem. The study further highlighted significant within-person associations. Any additional increases in social media exposure within a given year were linked to a concurrent decrease in self-esteem during that year and extended to the following year (+ 1 year). Instead, another study investigated how different online activities (posting status updates, posting photos of oneself with others, posting selfies, posting videos of oneself with others, and posting videos of oneself alone) were related to self-esteem and the results showed an indirect positive effect of self-presentation online on self-esteem via perceived online popularity (e.g. receiving “likes”) (Meeus et al., 2019).

The body of research indicates a generally negative relationship between social media use and self-esteem, regardless of the tool used to assess the variables and the type of study (cross-sectional or longitudinal). One of the key points is the relationship between problematic social media use and self-esteem. It would suggest that those with lower levels of self-esteem are more likely to engage in problematic use, perhaps seeking validation and connection through these channels. Despite the mixed criteria used to measure the duration of social media use, often relying on the subjective estimates of participants, a discernible negative relationship seems to emerge.

Adolescents Emotional Regulation and Social Media

Emotional regulation may be defined as the processes, both intrinsic and extrinsic, responsible for monitoring, evaluating, and modifying emotional reactions (Thompson, 1991). Emotions, viewed as biological processes, organize multi-system responses to significant environmental events. Emotional regulation becomes essential for flexibility in behavioral processes and the quick and efficient response to changing conditions. It is worth noting the relative paucity of empirical research in this area. The present review includes four cross-sectional studies and one longitudinal. In assessing emotional regulation in these transversal studies, validated scales have been utilized, such as the "Difficulties in Emotion Regulation" (Kaufman et al., 2016). This scale assesses difficulties in emotional functioning, including lack of emotional awareness, inability to accept one's emotions, difficulty engaging in goal-directed cognition and behavior, lack of ability to manage impulses, lack of emotional clarity, and difficulty accessing effective strategies to feel better when distressed. Higher scores on this scale reflect greater emotional regulation difficulties. Multiple studies found a negative correlation between problematic social media use and emotional regulation abilities (Gracia Granados et al., 2020; Peker & Nebi̇Oğlu Yildiz, 2022; Wartberg et al., 2021). Emotional regulation strategies such as limited access to emotion regulation strategies (r = 0.38, p < 0.01), nonacceptance of emotional responses (r = 0.32, p < 0.01), impulse control difficulties (r = 0.37, p < 0.01); difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior (r = 0.40, p < 0.01), lack of emotional awareness (r = 0.13, p < 0.01) and lack of emotional clarity (r = 0.34, p < 0.01) were all positively correlated with problematic social media use (Wartberg et al., 2021). Emotional suppression was positively correlated with social media addiction (r = 0.21, p < 0.01), while emotional reappraisal was negatively correlated with it (r = -0.08, p < 0.01) (Peker & Nebi̇Oğlu Yildiz, 2022).

Another study, confirms that both social context characteristics and emotion regulation contribute to explaining the frequency of social media use and problematic social media use among adolescents (Marino et al., 2020). Regarding social context, friendships impact adolescents' social media usage, where friends' perceptions of usage frequency correlate with individual use but not with problematic levels. On the other hand, social norms directly predict problematic social media use, suggesting that peer pressure to use social media frequently and expectations of constant online availability pose a direct risk, irrespective of actual usage frequency. A study of a sample of 457 adolescents over six years aimed to understand the predictors and outcomes associated with different patterns of social media time use (Coyne et al., 2019). Most adolescents (83%), categorized as moderate users, consistently maintained their social media usage over time. Another group (increasers: 12%) started with low social media use, gradually increasing to higher levels by the end of the study. The third group, referred to as peak users (6%), initially had low social media use that spiked rapidly after a few years and then returned to baseline levels. Moderate users had higher levels of self-regulation and lower levels of overall media use compared to both peak users and increased users. This study suggests that patterns of social media use may vary significantly among adolescents, and that such patterns may be associated with differences in levels of self-regulation and overall media use.

Adolescent’s Empathy and Social Media

Empathy is defined as “a cognitive and emotional understanding of another’s experience, resulting in an emotional response that is congruent with a view that others are worthy of compassion and respect and have intrinsic worth” (Barnett & Mann, 2013) Psychology often defined it as a multidimensional construct, encompassing cognitive and behavioral states (Davis, 1983). Empathic social skills play a crucial role in youth social development models and are key predictors of prosocial behavior, such as helping strangers, cooperative actions forgiveness and volunteering choices (Schroeder et al., 2015). Empathic ability is a construct closely related to emotional intelligence, since empathy is a skill closely related to understanding and using emotions (Segura et al., 2020). There is a limited body of research on the association between empathy and social media usage, with only three studies identified so far. Among these, one provides a cross-sectional perspective, while two offer longitudinal insights over time. Standardized questionnaires, such as the Basic Scale of Empathy (Jolliffe & Farrington, 2006) and Adolescent Measure of Empathy and Sympathy (Vossen et al., 2015), were utilized in two studies (Errasti et al., 2017; Vossen & Valkenburg, 2016). The third study (Stockdale & Coyne, 2020) employed a 7-item measure for empathy, though the specific tool was not detailed. One research study examined the frequency of use of two specific social media platforms, Facebook and Twitter, and found that people who were more active on these platforms, both in expressing their positive or negative feelings and in empathizing with others, had higher levels of affective and cognitive empathy (Errasti et al., 2017). Vossen and Valkenburg (2016) study results demonstrated a connection between the use of social media and a gradual enhancement of cognitive and affective empathy over time (2016). On the other hand, the second longitudinal study broadened the research perspective by exploring the motivations for using social networking sites over three years (Stockdale & Coyne, 2020). The study found a positive correlation between motivations such as seeking information, social connection, and boredom and pathological use of social media and empathy, and an inverse relationship between pathological use of social media and empathy (r = -0.19, p < 0.001).

Discussion

The integration of information and communication technologies into daily life has transformed how individuals, particularly adolescents, communicate and interact. The concept of ‘‘onlife’’, coined by Floridi to describe the contemporary experience of being hyper-connected in a digital world where the line between online and offline existence is becoming increasingly blurred, fits perfectly with the Gen Z experience (Floridi, 2015). This exponential and constant growth in the use of social platforms raises significant concerns, especially for adolescents who are known to be more susceptible to impulsivity and emotional challenges (Carvalho et al., 2023). While previous research has predominantly examined the role of emotional intelligence and problematic use of digital technologies more broadly (e.g., Internet addiction, gaming disorder), this study uniquely focuses on social media use. It also expands the scope of the search to including specific dimensions of emotional intelligence. This systematic review analyzed, organized and evaluated the existing literature on the relationship between emotional intelligence and social media use among adolescents, identifying a total of 25 articles. The findings of this study elucidate several associations linking adolescents' emotional intelligence, emotional regulation, self-esteem, and empathy with their patterns of social media consumption.

This review highlights the potential of emotional intelligence as a preventative factor against problematic behaviors in adolescents. Studies consistently show a link between lower emotional intelligence and increased problematic social media use. The Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model developed by Brand et al. (Brand et al., 2016) has been used as a theoretical framework in several studies. This model suggests that individual characteristics, affective and cognitive responses to internal or external stimuli, executive and inhibitory control, and decision-making behaviors influence the use of specific Internet applications or sites, impacting vulnerability or prevention of the development of Internet-related problems such as problematic social media use. These studies support the I-PACE model's thesis that various risk factors interact to create different problematic online behaviors. Notably, all the reviewed studies found that low emotional intelligence (considered as an individual characteristic) is a risk factor for problematic social media use.

Three studies added useful elements to the understanding of the relationship between emotional intelligence and problematic social media use. The results highlight that low levels of emotional intelligence are associated with higher levels of perceived stress and depressive symptoms, both of which are predictive of problematic social media us. Additionally, studies consistently show a concerning trend: females tend to have higher problematic social media use than males. This highlights a potential gender gap in social media navigation. Nevertheless, gender differences in emotional intelligence scores may depend on the instruments and theoretical approaches used (Joseph & Newman, 2010). Furthermore, the studies currently available have focused specifically on the problematic use of social media among adolescents, rather than exploring other aspects of the use of these platforms, such as, for example, the frequency of use, the methods of interactions, the type of shared content, and activities performed. The limitation of research in this area highlights the need for a wider variety of studies that can cover a broader range of social media behaviors and interactions.

Self-esteem is mainly driven by three processes: social comparison, social feedback processing, and self-reflection, and all of these processes are influenced by social media use (Krause et al., 2021). Studies on self-esteem and social media use supports this thesis by showing a consistent negative trend between the two variables. In explaining the relationship between SNS use and self-esteem, social comparison emerged as a frequently used concept. A study (Thorisdottir et al., 2019), included in this review, has shown that both active and passive social media use are positively related to social comparisons, which in turn are negatively related to self-esteem. Social networks allow numerical social comparisons (number of friends, followers, likes, retweets, etc.) (Errasti et al., 2017). According to a recent study carried out among pre-teens, around 39% of the sample indicated they regularly check the number of likes and views of their videos or photos, doing so often or always (Digennaro & Iannaccone, 2023). Engaging in these activities, along with the need for likes and followers, can have a negative impact on self-esteem of adolescents.(Meeus et al., 2019). Although online interactions can initially boost self-esteem through positive feedback, a potential downside emerges, as individuals, particularly those with lower self-esteem, may develop a dependency on social approval and engagement with social media (Martinez-Pecino & Garcia-Gavilán, 2019). Individuals with higher self-esteem seem to be less swayed by the quantity of "likes" they receive on social media when it comes to the likelihood of experiencing problematic internet use. This suggests that a solid sense of self-worth might serve as a buffer against the negative impacts of seeking validation through online interactions.

Regarding emotion regulation, findings highlight that the ability to regulate emotions contribute to the frequency or problematic nature of social media interactions in adolescence. Adolescents with difficulties in emotional functioning, including lack of emotional awareness, inability to accept one's emotions, difficulty engaging in goal-directed cognition and behavior, lack of ability to manage impulses, lack of emotional clarity handling emotions are more likely to frequently use social media, and to incur in dysfunctional social media use. Higher scores on the Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale are associated with higher problematic social media use, suggesting that deficits in emotional regulation or maladaptive regulatory strategies may be a risk factor for the development of social media addiction. Sometimes adolescents use these platforms as a maladaptive strategy to cope with difficult emotional states, attempting to find distraction and escape from emotional experiences (C. Andreassen & Pallesen, 2014). Yet, contrary to their intended relief, this behavior tends to result in a negative shift in mood (Hoge et al., 2017).

Research on the relationship between empathy and social media use is limited, with only three studies identified. social media activity, particularly emotional expression and empathic interaction, appears to be positively correlated with users' levels of empathy (Errasti et al., 2017). This may imply that conscious use of can enhance people's empathic abilities. On the other hand, the inverse correlation between pathological social media use and empathy suggests that certain online behaviors and motivations may hinder the development of empathy (Stockdale & Coyne, 2020). Furthermore, if excessive use is motivated primarily by boredom rather than meaningful interactions or specific goals, it could contribute to some sort of harmful addiction (Stockdale & Coyne, 2020).

Limitations

The limitations of this systematic review should be noted. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the high heterogeneity of the measures used across the included studies, which restricts our ability to infer the effect size of the reported associations. Almost all the studies included had cross-sectional design, which limited the possibility of making inferences about possible causal relationship between emotional intelligence and social media use. Another limitation is associated with the small number of studies included for some dimensions of emotional intelligence, therefore affecting the ability to draw robust conclusions. The potential influence of publication bias must be considered. This review did not include gray literature searches, which may have limited the scope of inclusion of research studies. In addition, the generalizability of findings to other cultural settings is limited because most studies have been conducted in Western cultural contexts.

Regarding the limitations of the included studies, it should be mentioned that variable relative to time spent on social media, rely on participants' perceptions and subjective estimates of their social media use. This introduces potential variability and limitations due to inaccuracies in participants' memory or perception of time. Another limitation is the use of self-report measures. Social desirability response bias may lead to inaccurate self-reports and erroneous study conclusions (Latkin et al., 2017). Furthermore, the studies relied primarily on convenience sampling, which limits the generalizability of the findings.

Future Directions and Implications

This review suggests a number of methodological gaps that should be considered in future research to deepen the current understanding of emotional intelligence and social media use. All studies use questionnaires to collect data, overlooking qualitative techniques that could more thoroughly capture the rich and varied experiences of adolescents in their interactions with social media. In order to be able to indicate causality and confidently identify the directions of these relationships, future studies need to employ longitudinal designs.

These of the current study may have important practical implications for the implementation of health prevention and promotion programs. According to a number of studies, emotional intelligence can be learned and improved through the implementation of intervention programs (Gilar-Corbi et al., 2019; Nelis et al., 2011). Emotional intelligence training can significantly improve emotion identification, management skills, emotion regulation and understanding, and general emotional skills. Adolescents with higher emotional intelligence are more aware of their emotions and behaviors, better able to regulate their emotions, and less likely to engage in problematic social media use. Improving adolescents' emotional intelligence skills may be the key to preventing the development of problematic behaviors, such as excessive use of the social media platform.

Conclusion

The associations between emotional intelligence and problematic social media engagement among adolescents have not been previously reviewed. The present systematic review suggests promising, but also challenging, preliminary evidence on the associations between emotional intelligence and problematic social media engagement among adolescents. Lower levels of emotional intelligence have consistently been linked to heightened engagement in problematic social media behaviors among adolescents across various studies, underscoring emotional intelligence's potential protective role against addiction. Furthermore, these studies have identified negative correlations between different aspect of social media use (time of social media use and addiction to social media) and adolescents' self-esteem, and emotional regulation, while social media use appeared to be positively correlated with empathy. These findings highlight the significance of emotional intelligence in shaping adolescents’ interactions with social media, suggesting that enhancing emotional intelligence skills could mitigate the risk of problematic social media use and promote healthier emotional development in this demographic.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Acar, I. H., Avcilar, G., Yazici, G., & Bostanci, S. (2022). The roles of adolescents’ emotional problems and social media addiction on their self-esteem. Current Psychology, 41(10), 6838–6847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01174-5

Alshakhsi, S., Chemnad, K., Almourad, M. B., Altuwairiqi, M., McAlaney, J., & Ali, R. (2022). Problematic internet usage: The impact of objectively recorded and categorized usage time, emotional intelligence components and subjective happiness about usage. Heliyon, 8(10), e11055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11055

Andreassen, C., & Pallesen, S. (2014). Social network site addiction—an overview. Current Pharmaceutical Design, 20(25), 4053–4061. https://doi.org/10.2174/13816128113199990616

Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006

Arrivillaga, C., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2022a). A mediated path from emotional intelligence to problematic social media use in adolescents: The serial mediation of perceived stress and depressive symptoms. Addictive Behaviors, 124, 107095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107095

Arrivillaga, C., Rey, L., & Extremera, N. (2022b). Problematic social media use and emotional intelligence in adolescents: Analysis of gender differences. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 15(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.32457/ejep.v15i1.1748

Barnett, G., & Mann, R. E. (2013). Empathy deficits and sexual offending: A model of obstacles to empathy. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(2), 228–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.010

Bar-On, R. (1997). The Emotional Quotient inventory (EQ-i): A test of emotional intelligence.

Blomfield Neira, C. J., & Barber, B. L. (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(1), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12034

Boer, M., Van Den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Boniel-Nissim, M., Wong, S.-L., Inchley, J. C., Badura, P., Craig, W. M., Gobina, I., Kleszczewska, D., Klanšček, H. J., & Stevens, G. W. J. M. (2020). Adolescents’ intense and problematic social media use and their well-being in 29 countries. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(6), S89–S99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.014

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Carvalho, C. B., Arroz, A. M., Martins, R., Costa, R., Cordeiro, F., & Cabral, J. M. (2023). “Help me control my impulses!”: Adolescent impulsivity and its negative individual, family, peer, and community explanatory factors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(12), 2545–2558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01837-z

Che, D., Hu, J., Zhen, S., Yu, C., Li, B., Chang, X., & Zhang, W. (2017). Dimensions of emotional intelligence and online gaming addiction in adolescence: The indirect effects of two facets of perceived stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01206

Ciacchini, R., Orrù, G., Cucurnia, E., Sabbatini, S., Scafuto, F., Lazzarelli, A., Miccoli, M., Gemignani, A., & Conversano, C. (2023). Social media in adolescents: A retrospective correlational study on addiction. Children (basel, Switzerland), 10(2), 278. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020278

Ciarrochi, J. V., Chan, A. Y. C., & Caputi, P. (2000). A critical evaluation of the emotional intelligence construct. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(3), 539–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00119-1

Ciarrochi, J., Chan, A. Y. C., & Bajgar, J. (2001). Measuring emotional intelligence in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(7), 1105–1119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00207-5

Cingel, D. P., & Olsen, M. K. (2018). Getting over the hump: Examining curvilinear relationships between adolescent self-esteem and facebook use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 62(2), 215–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2018.1451860

Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Holmgren, H. G., & Stockdale, L. A. (2019). Instagrowth: A longitudinal growth mixture model of social media time use across adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(4), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12424

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Drukker, M., Weltens, I., Van Hooijdonk, C. F. M., Vandenberk, E., & Bak, M. (2021). Development of a methodological quality criteria list for observational studies: The observational study quality evaluation. Frontiers in Research Metrics and Analytics, 6, 675071. https://doi.org/10.3389/frma.2021.675071

Errasti, J., Amigo, I., & Villadangos, M. (2017). Emotional uses of facebook and twitter: Its relation with empathy, narcissism, and self-esteem in adolescence. Psychological Reports, 120(6), 997–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117713496

Ferrara, E., & Yang, Z. (2015). Measuring emotional contagion in social media. PLoS ONE, 10(11), e0142390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0142390

Floridi, L. (Ed.). (2015). The onlife manifesto. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: A theory of multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

Gilar-Corbi, R., Pozo-Rico, T., Sánchez, B., & Castejón, J.-L. (2019). Can emotional intelligence be improved? A randomized experimental study of a business-oriented EI training program for senior managers. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0224254. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0224254

Gisbert-Pérez, J., Badenes-Ribera, L., & Martí-Vilar, M. (2024). Emotional intelligence and gaming disorder symptomatology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adolescent Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00233-3

Global Web Index. (2023). Global Web Index’s Social media behind the screens (2023 Trend Report).

Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional intelligence (10th anniversary trade pbk. ed). Bantam Books.

Gracia Granados, B., Quintana-Orts, C. L., & Rey Peña, L. (2020). Regulación emocional y uso problemático de las redes sociales en adolescents: El papel de la sintomatología depresiva. Health and Addictions/salud Y Drogas., 20(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.21134/haaj.v20i1.473

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2017). The relations among social media addiction, self-esteem, and life satisfaction in university students. Social Science Computer Review, 35(5), 576–586. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439316660340

Hoge, E., Bickham, D., & Cantor, J. (2017). Digital media, anxiety, and depression in children. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement_2), S76–S80. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758G

Hughes, D. J., & Evans, T. R. (2018). Putting ‘emotional intelligences’ in their place: Introducing the integrated model of affect-related individual differences. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02155

Jolliffe, D., & Farrington, D. P. (2006). Development and validation of the basic empathy scale. Journal of Adolescence, 29(4), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.010

Joseph, D. L., & Newman, D. A. (2010). Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 54–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017286

Kaufman, E. A., Xia, M., Fosco, G., Yaptangco, M., Skidmore, C. R., & Crowell, S. E. (2016). The Difficulties in emotion regulation scale short Form (DERS-SF): Validation and replication in adolescent and adult samples. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(3), 443–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-015-9529-3

Kelly, Y., Zilanawala, A., Booker, C., & Sacker, A. (2018). Social media use and adolescent mental health: Findings from the uk millennium cohort study. EClinicalMedicine, 6, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.12.005

Kircaburun, K., Griffiths, M. D., & Billieux, J. (2019). Trait emotional intelligence and problematic online behaviors among adolescents: The mediating role of mindfulness, rumination, and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 142, 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.11.024

Korte, M. (2020). The impact of the digital revolution on human brain and behavior: Where do we stand? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 22(2), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.2/mkorte

Krause, H.-V., Baum, K., Baumann, A., & Krasnova, H. (2021). Unifying the detrimental and beneficial effects of social network site use on self-esteem: A systematic literature review. Media Psychology, 24(1), 10–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1656646

Kun, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2010). Emotional intelligence and addictions: A systematic review. Substance Use & Misuse, 45(7–8), 1131–1160. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826080903567855

Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Allen, M. S. (2016). Emotional intelligence in sport and exercise: A systematic review: Emotional intelligence. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 26(8), 862–874. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12510

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Tobin, K. E. (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.005

Law, K. S., Wong, C.-S., & Song, L. J. (2004). The construct and criterion validity of emotional intelligence and its potential utility for management studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.483

Lee, A. Y., Katz, R., & Hancock, J. (2021). The role of subjective construals on reporting and reasoning about social media + use. Social Media Society, 7(3), 205630512110353. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211035350

Leite, K. P., Martins, F. D. M. P., Trevizol, A. P., Noto, J. R. D. S., & Brietzke, E. (2019). A critical literature review on emotional intelligence in addiction. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 41(1), 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2018-0002

Liu, Q.-Q., Yang, X.-J., & Nie, Y.-G. (2023). Interactive effects of cumulative social-environmental risk and trait mindfulness on different types of adolescent mobile phone addiction. Current Psychology, 42(20), 16722–16738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02899-1

Livet, A., Boers, E., Laroque, F., Afzali, M. H., McVey, G., & Conrod, P. J. (2022). Pathways from adolescent screen time to eating related symptoms: A multilevel longitudinal mediation analysis through self-esteem. Psychology & Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2022.2141239

Llamas-Díaz, D., Cabello, R., Megías-Robles, A., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2022). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The association between emotional intelligence and subjective well-being in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 94(7), 925–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12075

Marino, C., Vieno, A., Altoè, G., & Spada, M. M. (2017). Factorial validity of the problematic facebook use scale for adolescents and young adults. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.004

Marino, C., Gini, G., Angelini, F., Vieno, A., & Spada, M. M. (2020). Social norms and e-motions in problematic social media use among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 11, 100250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2020.100250

Martinez-Pecino, R., & Garcia-Gavilán, M. (2019). Likes and problematic instagram use: The moderating role of self-esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(6), 412–416. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0701

Mavroveli, S., Petrides, K. V., Sangareau, Y., & Furnham, A. (2009). Exploring the relationships between trait emotional intelligence and objective socio-emotional outcomes in childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(2), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709908X368848

Meeus, A., Beullens, K., & Eggermont, S. (2019). Like me (please?): Connecting online self-presentation to pre- and early adolescents’ self-esteem. New Media & Society, 21(11–12), 2386–2403. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819847447

Mérelle, S. Y. M., Kleiboer, A. M., Schotanus, M., Cluitmans, T. L. M., Waardenburg, C. M., Kramer, D., van de Mheen, D., & van Rooij, A. J. (2017). Which health-related problems are associated with problematic video-gaming or social media use in adolescents? A Large-Scale Cross-Sectional Study., 14(1), 11–19.

Monacis, L., de Palo, V., Griffiths, M. D., & Sinatra, M. (2017). Social networking addiction, attachment style, and validation of the Italian version of the bergen social media addiction scale. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(2), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.023

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11(2), 354–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021554

Peker, A., & Nebi̇Oğlu Yildiz, M. (2022). Examining the relationships between adolescents’ emotion regulation levels and social media addiction. Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences, 12(3), 564–569. https://doi.org/10.33808/clinexphealthsci.869465

Petrides, K. V. (2009). psychometric properties of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire (TEIQue). In J. D. A. Parker, D. H. Saklofske, & C. Stough (Eds.), Assessing emotional intelligence springer. US.

Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15(6), 425–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.416

Petrides, K. V., Sangareau, Y., Furnham, A., & Frederickson, N. (2006). Trait emotional Intelligence and children’s peer relations at school. Social Development, 15(3), 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00355.x

Petrides, K. V., Furnham, A., & Mavroeli, S. (2007). Trait emotional intelligence: Moving forward in the field of EI. Oxford University Press.

Pino, O., & Mastromarino, S. (2023). Impact of emotional intelligence (EI) on social network abuse among adolescents during COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 94(3), e2023150. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v94i3.14468

Rodgers, R. F., Slater, A., Gordon, C. S., McLean, S. A., Jarman, H. K., & Paxton, S. J. (2020). A biopsychosocial model of social media use and body image concerns, disordered eating, and muscle-building behaviors among adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(2), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01190-0

Rosenberg, M. (1989). Society and the adolescent self-image (Rev. ed., 1st Wesleyan ed). Wesleyan University Press.

Sahin, C. (2018). Social media addiction scale-student form: The reliability and validity study. 17: 169–182.

Salovey, P., Bedell, B. T., Detweiler, J. B., & Mayer, J. D. (1999). Coping intelligently: Emotional intelligence and the coping process. C. R. Snyder.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. https://doi.org/10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Sanchez-Alvarez, N., Extremera, N., & Fernandez-Berrocal, P. (2015). Maintaining life satisfaction in adolescence: Affective mediators of the influence of perceived emotional intelligence on overall life satisfaction judgments in a two year longitudinal study. Frontiers in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01892

Schivinski, B., Brzozowska-Woś, M., Stansbury, E., Satel, J., Montag, C., & Pontes, H. M. (2020). Exploring the role of social media use motives, psychological well-being, self-esteem, and affect in problematic social media use. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 617140. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.617140

Schroeder, D. A., Graziano, W. G., & Davis, M. H. (2015). Empathy and prosocial behavior. In D. A. Schroeder & W. G. Graziano (Eds.), The oxford handbook of prosocial behavior. Oxford University Press.

Segura, L., Estévez, J. F., & Estévez, E. (2020). Empathy and emotional intelligence in adolescent cyberaggressors and cybervictims. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4681. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134681

Shafi, R. M. A., Nakonezny, P. A., Miller, K. A., Desai, J., Almorsy, A. G., Ligezka, A. N., Morath, B. A., Romanowicz, M., & Croarkin, P. E. (2021). Altered markers of stress in depressed adolescents after acute social media use. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.055

Stockdale, L. A., & Coyne, S. M. (2020). Bored and online: reasons for using social media, problematic social networking site use, and behavioral outcomes across the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 79(1), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.010

Sural, I., Griffiths, M. D., Kircaburun, K., & Emirtekin, E. (2019). Trait emotional intelligence and problematic social media use among adults: The mediating role of social media use motives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0022-6

Tang, L., Omar, S. Z., Bolong, J., & Mohd Zawawi, J. W. (2021). Social media use among young people in china: A systematic literature review. SAGE Open, 11(2), 215824402110164. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211016421

Thompson, R. A. (1991). Emotional regulation and emotional development. Educational Psychology Review, 3(4), 269–307.

Thorisdottir, I. E., Sigurvinsdottir, R., Asgeirsdottir, B. B., Allegrante, J. P., & Sigfusdottir, I. D. (2019). Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(8), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2019.0079

Thorndike, E. L. (1920). Intelligence and its uses. Harper’s Magazine, 140, 227–235.

Valkenburg, P., & Peter, J. (2013). The effects of internet communication on adolescents’ psychosocial development: An assessment of risks and opportunities. In Media Effects/Media Psychology.

Valkenburg, P., Beyens, I., Pouwels, J. L., Van Driel, I. I., & Keijsers, L. (2021a). Social media use and adolescents’ self-esteem: Heading for a person-specific media effects paradigm. Journal of Communication, 71(1), 56–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa039

Vossen, H. G. M., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). Do social media foster or curtail adolescents’ empathy? A longitudinal study. Computers in Human Behavior, 63, 118–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.040

Vossen, H. G. M., Piotrowski, J. T., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2015). Development of the adolescent measure of empathy and sympathy (AMES). Personality and Individual Differences, 74, 66–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.040

Wang, Y., Yang, Z., Zhang, Y., Wang, F., Liu, T., & Xin, T. (2019). The effect of social-emotional competency on child development in Western China. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01282

Wartberg, L., Thomasius, R., & Paschke, K. (2021). The relevance of emotion regulation, procrastination, and perceived stress for problematic social media use in a representative sample of children and adolescents. Computers in Human BeHAVIOR, 121, 106788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106788

Woods, H. C., & Scott, H. (2016). #Sleepyteens: Social media use in adolescence is associated with poor sleep quality, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence, 51, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.05.008

World Health Organization,. (2015). Global strategy for women’s, children’s and adolescents’ health (2016–2030) (pp. 1–10) [A72/30]. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_30-en.pdf

Xu, X., Han, W., & Liu, Q. (2023). Peer pressure and adolescent mobile social media addiction: Moderation analysis of self-esteem and self-concept clarity. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1115661. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1115661

Yang, H., Wang, Z., Elhai, J. D., & Montag, C. (2022). The relationship between adolescent emotion dysregulation and problematic technology use: Systematic review of the empirical literature. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(2), 290–304. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2022.00038

Funding

This study was funded by ECS Rome Technopole (CUP H33C22000420001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP conceived of the study, participated in its design, coordination and data collection/interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript; SD conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Consent for Publication

During the preparation of this work, the authors used DeepL in order to refine the text. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Piccerillo, L., Digennaro, S. Adolescent Social Media Use and Emotional Intelligence: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Res Rev (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00245-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-024-00245-z