Abstract

Measurement of development is important for economists, academicians and policy makers as it deals with broader issues such as satisfaction of basic human needs and goals, well-being, environment protection and of course economic growth. There have been several attempts to construct various indices for measuring development ever since the use of growth in GDP was found to be inadequate. While the use of composite indices was a significant step in this direction, the existing ones are widely criticized on its limited scope while capturing the various dimensions of development process. Moreover, they also lacked in its methodology of aggregation and weighting scheme, where equal weights for its components were taken in most of the cases. In this study, we make an attempt to construct a broad-based development index (BBDI) capturing the overall development process under various dimensions such as society, sustainability, economy and institutions. Apart from its wide coverage, our index is also different from the existing ones in terms of its weighting, where we have used principal component analysis for deriving the variable weights. BBDI is then aggregated for 102 countries measuring their development process from 1996 through 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the past few decades, we have seen the concept of development continually and dynamically changing along with economic and social progress. There has been a significant change in the way in which the term development is defined and even measured. In the 1950s and early 1960s, economic development was viewed as continuous increases in national income in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). From what was once considered to be just an increase in national income, the concept of development has come long way where currently it is defined in terms of economic, social, political and institutional mechanisms that could bring about rapid and large-scale improvement in the standard of living of the people (Todaro and Smith 2011). In recent times, the emphasis is shifted toward sustainability of development (UNDP 2016). It aims at achieving balance between the social and economic dimensions of the society along with a sustainable approach to production and improvement in the quality of life.

An equally important aspect of development is to measure it in accordance with its changing definitions. This is important as development is generally taken as the broader objective of any economic policy irrespective of specific goals they are designed to achieve. Growth rates in GDP and related measures could have been sufficient in the earlier days when the scope of development was limited to mere economic well-being. However, with development getting broader with respect to its coverage, it is important that the measure of development should also encompass wider aspects of human well-being (Sen 1983; Todaro 1989). Nevertheless, this is in no means an easy task as one has to combine various dimensions of development into a single measure reflecting the overall development process (Decancq and Lugo 2009).

Several indices have been proposed as an alternative to GDP while measuring development. A few examples could be level of living index by United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD, 1966), Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) by Overseas Development Council in 1980, Human Development Index (HDI) by UNDP in 1990, Happy Planet Index in 2006 by the New Economic Foundation and many. However, as noted by commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress in Stiglitz et al. (2009), the existing measures of development are inadequate to capture the overall development process as they are confined to some specific aspects of development.

In this context, this paper makes an attempt to develop a broad-based index for development by involving some variables in terms of economy, society, sustainability and institutions. This broad-based index differs from the existing indices on two counts: first, the selection of variables and second, weighting scheme in construction of index. While choosing variables, we have followed the ‘means and end’ criteria, where the variable either contribute as a means of development or is its end result. However, based on availability of uniform data across the countries, we have narrowed down on 15 variables, namely expected years of schooling, mean year of schooling, access to drinking water, sanitation facilities, life expectancy, infant mortality rate, non-renewable and renewable energy consumption, forest cover, CO2 emission, real per capita GDP, inflation rate, investment rate, rule of law and voice and accountability. These variables are then used in construction of index by obtaining weights through principal component analysis (PCA) and termed it as a broad-based development index (BBDI). This paper contributes to the existing literature on measurement of development in terms of new set of variables which represents the development of all spheres. Also, it offers an alternative method for construction of development index.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Issues involved in measurement of development such as selection of variables and the weighting scheme are presented in ‘Review of literature’ section. This is followed with a brief discussion on data and variables used for the construction of index. In ‘Construction of the board based development index: results and discussion,’ we take up construction of the broad-based development index. Finally, in ‘Summary and conclusions’ section, we sum up the study with summary and conclusions.

Review of literature

A brief review of the literature is presented here with respect to variable and indicators of development and issues related to its aggregation.

Measurement of development: variables and indicators

Coming to various measures of development, the most common and traditional one has been the growth rates of GDP. Even formal economic models put forth by authors like Solow (1956), Myrdal (1957) and Rostow (1959) have used various measures of growth in national income as an indicator of development. In spite of its drawbacks in measuring the broad dimensions of development, GDP has been the popular indicator on the notion that economic development in terms of increasing income directly contributes to well-being and better standard of living (Lucas 1988; Michaelson et al. 2009).

However, the use of GDP as a measure of development has been criticized by many like Sen (1983), Goossens et al. (2007), Stiglitz et al. (2009), Wilkinson et al. (2010) and Schepelmann et al. (2010). According to Sen (1983), economic growth cannot be treated as an end in itself rather; it should be taken as means to enhance lives with better standard of living. The argument is that the growth in GDP fails to account for distribution of income among individuals, which has a considerable effect on individual and social well-being. Moreover, as pointed out by McGranahan et al. (1972) and Costanza et al. (2009) and many others, GDP is merely a monetary measure of level of production which reflects regional growth rather than the overall progress of the society and is thus inadequate to capture the overall development process. The way out to this problem clearly lies in measuring development as a multidimensional concept involving various indicators of development which goes beyond income and related measures (Todaro 1989; Booysen 2002; Greco et al. 2016).

One of the pioneers in this field has been the UN Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD) which had taken several initiatives for the formulation of composite development indices. Drewnowski and Scott (UNRISD, 1966) developed the ‘level of living index’ which was defined in terms of ‘the level of satisfaction of the needs of the population as measured by the flow of goods and services enjoyed in a unit of time.’Footnote 1 This index covered 20 countries and had education, health, housing, nutrition, leisure, security and income surplus as the indicators of level of living. Later, UNRISD (1972) under McGranahan et al. came up with ‘Socio Economic Development Index’ based on 18 core indicators which consist of 9 economic indicators and 9 social indicators. Though this was a major upgrade over the level of living index, the socioeconomic development index was criticized for having high intercorrelation among indicators leading to insensitivity of the composite index to the variables (Hicks and Streeten 1979). According to Perthel (1981), both the UNRISD indices are deficient as they fail to account for essential components of development such as population structure, inequality, justice and so on.

In 1975, United Nation ECOSOC analyzed development based on seven indicators, namely life expectancy, literacy, energy, manufacturing share of GDP and exports, employment outside agriculture and number of telephones. Though this was widely accepted and used for about 140 countries, a major criticism was that the number of indicators in the index was biased toward economic factors over social indicators. On contrary, along the same time, the Overseas Development Council (1980) under the guidance of Morris has come up with Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) which measured development purely on social factors. The PQLI was an equi-weighted index based on three indicators, namely infant mortality, life expectancy and literacy. Their approach in selection of variables was based on the criteria that development should lead to fulfillment of minimum human needs. However, the major drawback was that basic human needs go beyond what the chosen variables could capture.

A more comprehensive view of development was proposed by the World Bank in its 1991 World Development Report (World Bank 1991). It asserted that development leading to better quality of life should encompass better education, proper standard of health and nutrition, less poverty, cleaner environment, more equality of opportunity, greater individual freedom and richer cultural life. On the similar lines, the Human Development Report published by the United Nations in 1995 also identifies the purpose of development as enlargement of all human choices and not just increase in income. Measuring this broader concept of development, Mahbub ul Haq devised the Human Development Index (HDI) in the year 1990 and later United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) started using this index as the measure of economic development. It is calculated based on three dimensions of human development, namely (1) a long and healthy life measured by life expectancy, (2) knowledge measured using expected years of schooling and mean years of schooling and finally, (3) standard of living calculated on the basis of GNI per capita.Footnote 2 Though this index has gained popularity, there are several criticisms with regard to the selection of its variables and aggregation methods. While components of HDI capture development to some extent, they are in no means complete as development in the recent times implies far more than just literacy, good health and quality of living could capture (Desai 1991; Srinivasan 1994; Streeten 1995; Ravallion 1997; Noorbaksh 1998; Lind 2004; Decancq and Lugo 2009; Santos and Santos 2014).

However, in the recent times, the term development has become much wider than its earlier definitions. In the year 2000, the United Nations came up with Millennium Development GoalsFootnote 3 where it looked at an eightfold path to development in terms of eradication of poverty and hunger, universal primary education, gender equality and women empowerment, reduction of child mortality, improvement of maternal health, fighting chronic diseases like malaria and HIV/AIDS, environmental sustainability and global partnership. Later in 2016, the UNDP proposed what is popularly known as the Sustainable Development Goals,Footnote 4 where the emphasis was on sustainability of the development. Apart from the specific targets for the Millennium Development Goals, the Sustainable Development Goals also consider new dimensions of development such as climate change, economic inequality, innovation, sustainable consumption and peace and justice.

Given these new and broader dimensions to development, the measures capturing it also should take into account for these changes. Nevertheless, a major difficulty in constructing such a measure is on two counts: The first and foremost problem is with respect to availability of uniform data for these indicators across the countries which are comparable (Ginsberg et al. 1986). Nevertheless, in recent times it is not a serious limitation with reasonable improvement in maintaining large datasets by institutions such as the World Bank, IMF, OECD and UN. However, even if one manages to reach at common variables for the chosen countries, the second problem is in choosing an appropriate methodology to aggregate them into a single composite index. A common practice is to aggregate the variables into a composite index by assigning weights. In a composite index, weights refer to relative importance of the variable while comparing with other variables in the index. According to Rawls (1971), assigning weights to a composite index referred to as ‘index problem’ is one of the major tasks involved in its construction. Saisana et al. (2005), Grupp and Mogee (2004) and Grupp and Schubert (2010) have shown how change of weights could be used to manipulate the results. The question here is on how to choose an appropriate weight for the variables in consideration.Footnote 5

Aggregation of the variables: issue of weights in index

What has been the practice so far is to assign equal weights for all the variables. Few examples for this could be level of living index, PQLI, HDI and so on. From the definition of weights, equal weights imply that all the variables in the index contribute equally to the measured phenomenon. For example, in case of HDI, the factors such as education, health and standard of living contribute equally to human development. By treating all the variables/indicators equally, identical weights fail to account for the difference between the important and less important variables (Todaro 1989; Rao 1991; Greco et al. 2017, 2018). Major reasons for choosing equal weights are on account of its simplicity in calculation, lack of theoretical justification for differential weights, inadequate statistical or empirical knowledge (Greco et al. 2018).

Alternatively, one could choose an appropriate weighting scheme to aggregate the chosen variables. Weighting schemes are broadly divided into two categories: The first is based on participatory models such as budget allocation process (BAP), analytic hierarchy process (AHP) and conjoint analysis (CA). In BAP, the weights are based on average of points given by the panel members to each of the variables/indicators, whereas in AHP given by Saaty (1987), weights follow an ordinal scale where the variables/indicators are given weights based on pairwise comparisons (OECD 2008). Finally, in CA, at first the preferences are derived from a set of given alternatives and the weights are obtained based on the marginal rate of substitution. However, a major drawback in all these techniques is that the weights are given as subjective manner. If the panel members lack adequate information on relevance of variables/indicators in the measured phenomenon, then the results may be biased (Greco et al. 2018). Moreover, participatory analysis can lead to inconsistent results and subjectivity while dealing with large number of indicators (OECD 2008).

The second category of weighting scheme relies on data for deriving weights. Data-driven methods use mathematical function to derive weights and are considered better than the participatory methods as the former is devoid of subjectivity (Grupp and Mogee 2004; Ray 2008). Weights based on correlation are one of the most commonly used techniques, where the weights are based on the correlation coefficients (Booysen 2002). In simple terms, significantly higher correlation implies higher weight. A major drawback with this technique is that correlation always need not imply causation or the absence of correlation cannot be taken as the absence of causality. Thus, weights based on statistically significant correlation coefficients need not always show the true relation (OECD 2008). This problem can be addressed by moving away from correlation-based weights to the ones driven by linear regression parameters, as the regression coefficients also indicate causality.

However, while using linear regression techniques, we are assuming that the independent variables are linearly related to the chosen dependent variable. This according to Saisana et al. (2005) may not be appropriate in case of composite indices. Moreover, a much bigger problem is the choice of dependent variable itself. In the regression technique, we need a dependent variable that is an indicator of what the index proposes to capture. In case of a composite development index, if one chooses GDP as the dependent variable, then it would altogether fail the purpose of composite index which is devised to move away from giving overwhelming importance to GDP as measure of development (Costanza et al. 2009; Stiglitz et al. 2009). This issue of choosing a dependent variable can be tackled through principal component analysis (PCA), where data are represented as series of linear equations in such a way that the variance in original set of variables is explained in each of the equations. These equations are nothing but principal components which are extracted from original set of variables using their correlation matrix (Johnson and Wichern 1999). However, an important criterion for applying this technique is that the correlation between the chosen variables should be high.

The most useful property of PCA is its advantage while dealing with ‘double counting’ by correcting overlapping information in two or more variables (OECD 2008). This has made PCA one of the most popular choices while constructing composite indices involving large number of variables that are interrelated. However, while using PCA, one should be cautious about the statistical properties of the data. Most important being the need for continuous nature of the data set which are in the same units of measurement (Greco et al. 2018). This aspect can, however, be tackled either through normalization or standardization of the data sets. Several indices have been developed using PCA since it was introduced by Pearson (1901). The first one with respect to development indices was weighted Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI) developed by Ram (1982). Later, Noorbakhsh (1996) and Lai (2003) used PCA to weigh the components of HDI. Recently, Guptha and Rao (2018) have used PCA to construct financial institution development index, financial market development index and financial system development index for the BRICS economics.

From the foregoing discussion, one could note that the existing measures of development are inadequate to capture the overall development process. Their drawbacks are with respect to the selection of variables and methodology for aggregation, where variables are given equal weights. Keeping this in mind, we construct a development index that could address these shortcomings.

Data, variables and its theoretical significance

In this section, we turn to discuss about the data and variables used in this study. However, before going into details about data, variables and its notations, it is important to understand and define what one is trying to capture. A good measure for development should primarily reflect development process in accordance with its theoretically considerations. As mentioned earlier, the definition for development has evolved along the time from its singular focus on growth rate of GDP to a multidimensional process encompassing various aspects that effects human well-being. In the recent times, as suggested by UNDP,Footnote 6 besides the traditional factors such as economic, social, institutional, political setup in a country, sustainability of development should also be considered as one of the significant features of development. Taking all these factors into consideration, we define development as a process that is measured by improvement in social, economic, institutional and environmental factors. In this context, in addition to traditional socioeconomic variables, we include factors like pattern of energy consumption, use and availability of natural resources, rule of law and voice and accountability that plays a vital role in determining sustainability of development.

Data: sources and notation

The data sets are obtained from official sources such as UNESCO and the World Bank. The data for our study cover 102 countries for a time period from 1996 to 2015. The chosen variables are classified under indicators each one is intended to measure. A schematic presentation of variables, its notation, sources and corresponding list of indicators are presented in Table 1.

Education, quality of health, access to clean water and sanitation facilities are the primary objectives of development as advocated by UNDP in its sustainable development goals. In our study, level of education is captured through expected years of schooling (EYS) and mean year of schooling (MYS) where EYS is the number of years of schooling that a student can expect to receive from the time of enrollment. According to UNESCO (2013), EYS shows ‘the overall level of development of an educational system in terms of the number of years of education that a child can expect to achieve,’ whereas MYS is the average number of completed years of schooling which according to Chiswick et al. (1997) gauge education as an input for human capital formation. This formulation is in line with HDI, where EYS and MYS are used as proxy for knowledge dimension and education attainment, respectively. In this way, as pointed out by Morris (1979), these two can be taken as the means to development.

Quality of health is measured in terms of life expectancy (LEX) and infant mortality rate (IMR). Life expectancy is the average years that the person in a country is expected to live. This captures longevity of human life that reflects the quality of health services and amenities available to the population. Long and healthy life will enable individuals to be more productive in their income generating activities (Bloom and Canning 2009). This aspect of LEX makes it means as well as end of development. IMR is the number of deaths under 1 year of age for every thousand live births. While LEX indicates the standard of overall health services, IMR points toward condition of primary health services, access to health services and social inequality (Sen 1998; Arntzen and Andersen 2004; Lindelow 2006). IMR relates to end result of development, i.e., a developed society should move toward lower infant mortality rates indicating the presence of better health systems and quality of life.

Apart from education and health, we believe that the social aspect of development is also reflected through access to clean drinking water and sanitation facilities. Improved access to these facilities can lead to better health standards among the people, which could further enhance their participation in productive activities (WHO 2007). Moreover, Bloom et al. (2004) have linked lack of access to water and sanitation facilities to higher drop out ratio in schools. This argument is primarily based on two reasons. Firstly, lack of these facilities may increase cases of illness leading to lower class participation. Secondly, in rural areas, particularly for girls, their class attendance may drop as they need to spend significant part of their day in fetching water from distant sources. Finally, as noted by United Nations General Assembly in 2010, access to safe drinking water and sanitation facilities are essential human rights. Being a basic human right along with its role in aiding better education and health, water and sanitation facilities can be taken as means as well as ends to development. Keeping this in mind, we measure access to clean drinking water and sanitation facilities through percentage of people having access to improved water facilities (IWF) and sanitation facilities (ISF), respectively.

Energy and environment are important for development as far as its sustainability is concerned. As defined by Brundtland Report (1987), sustainable development is that which ‘meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.’ Efficient utilization of energy and environment is the key here. In this context, we measure energy use in terms of non-renewable energy consumption (NEG) and renewable energy consumption (REG). Here, both NEG and REG can contribute to development as inputs (means) for higher production and economic growth. However, inefficient use of non-renewable energy could threaten the sustainability of development itself. According to reports on sustainable energy for development by German Development Cooperation in the Energy Sector (2014), it is use of renewable energy that could enhance intertemporal access to energy without tampering with the climate and environment. For our index, we also define sustainable development in terms of climate and environment, where forest covers FRT and CO2 emissions CO2 are taken as the proxies. With respect to sustainability of development, higher forest covers and lower CO2 emissions should be considered as the end result.

Better economic conditions are taken as proxy for higher standard living which is means as well as an end to development process. In this context, we measure economic performance of an economy under three heads, namely (1) real per capita income (GDP), (2) rate of inflation (INF) and (3) capital formation-to-GDP ratio (GCF), where GDP is of traditional importance and is taken as a measure of economic growth (Michaelson et al. 2009). Moreover, with higher income, people could have better access to market and resources which may enhance their well-being. INF is taken as proxy for uncertainty with respect to prices. Given the fact that prices generally tend to move upwards, higher prices could lower the purchasing power denying access to necessities for living (Stiglitz 2015). This is especially true for majority of the rural poor who are just earning subsistence level of wages. Finally, GCF measures level of capital formation in the economy. With higher capital formation, we expect better infrastructural facilities that could enhance level of production and incomes which in turn could augment the standard of living (Ansar et al. 2016).

Finally, we have rule of law ROL and voice and accountability VAA capturing the quality of governance and institutional aspects of development. As pointed out by North (1990), institutions and governance are ‘humanly devised constraints’ that play a vital role in shaping human interactions in the society. ROL is defined as the extent to which people have confidence in and follows the rules of society such as quality of contracts, property rights, law and order. This is an enabling condition for development in terms of basic social order and security which is essential for effective implementation of other development activities (Sen 2006; World Bank 2012; Berg and Desai 2013). However, VAA measures freedom of citizens in selecting their government, expression, association and media. Freedom as advocated by Sen (1998) is an end as well as means to development. According to him, development is dependent on ‘free agency’ of people and the end result of it should be measured in terms of enhancement of freedom. This aspect is also stressed by Goetz and Jenkins (2002) in human development report of UNDP. Moreover, as per the sustainable development goals by UNDP, together promotion of rule of law and human rights are important for sustainable development.

After the selection of variables, the next task is to obtain appropriate weights and then aggregate them into a composite index that could reflect the overall development process. As mentioned earlier, selection of weights is an important step involved in construction of development index reflecting the relative importance of variables in the index. We have employed principal component analysis (PCA) to derive the weights. For detailed discussion on PCA, one could refer standard multivariate texts such as Johnson and Wichern (1999).

Construction of the board based development index: results and discussion

Here, we employ a multivariate statistical technique PCA in construction of BBDI. Before proceeding with PCA, we have to ensure that the variables are measured identically. For this purpose, we normalize variables transforming them into pure, dimensionless, numbers which are comparable. Moreover, having multiple variables measuring the overall development process, some variables may have a positive association with development, while others may have a negative relation. In such cases, normalization of the variables is a required condition, such that an increase in the normalized variables will correspond to an increase in the overall development (Mazziotta and Pareto 2012). There are several methods available for normalization of datasets, the popular ones being ranking, min–max transformation, z scores and indicization. For our study, we have considered the min–max transformation method as it provides a linear transformation on a range of original data between 0 and 1. This is done as follows:

where \( z_{ti}^{(j)} \) is the normalized value of ith variable at time t for jth country.\( {\text{Min}}(X_{i}^{(j)}) \) and \( {\text{Max}}(X_{i}^{(j)}) \) represents the minimum and maximum value of ith variable for jth country, respectively.

Having normalized the variables, the next step is to arrive at a common weight for each of the variables that is applicable across the countries. For this purpose, using the normalized data for all the 102 countries, we calculate the average value for each of the variable at each point of time from 1996 through 2015. For example, the value for inflation in 1996 is calculated by summing the rates of inflation from all the 102 countries for 1996 and then dividing by 102. Formally, for time period t, the average value of ith variable is given by:

where \( \bar{z}_{ti} \) is the average value of ith variable at time period t and \( z_{ti}^{(j)} \) represents the value of ith variable for jth country at time period t. In our case, \( i = 1, 2, \ldots 15 \); \( j = 1, 2, \ldots 102 \) and t ranges from 1996 to 2015. Now, these averages of the normalized variables are used in PCA to derive the weights.

Nevertheless, before we proceed with PCA, a final step could be to test for suitability of PCA for the averages of the normalized variables. This is done using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, which is a measure of sampling adequacy. For PCA, Kaiser (1974) recommends a minimum KMO value of 0.5. Though there are various opinions on acceptable level of KMO value, the general consensus is that KMO between 0.5 and 0.7 is considered ‘mediocre,’ value between 0.7 and 0.8 is ‘good’, range between 0.8 and 0.9 is ‘great,’ and KMO values in excess of 0.9 are ‘superb’ (Hutcheson and Sofroniou 1999). For our data, the KMO value is 0.78 (see Table 2) indicating adequacy of performing PCA. Further, we also check for the strength of relationship among variables using Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Here, the null hypothesis is that the variables in the population correlation matrix are uncorrelated. Our results indicate the rejection of null hypothesis implying strong relationship among the variables (see Table 2).

As data satisfies the adequacy test, we now proceed with PCA. Since we have 15 variables, the PCA will generate 15 principal components of which a few are selected for calculating the weights. The selection of principal components is based on eigen values, where the minimum value is expected to be more than one. In our case, the principal component one, two and three satisfies this criterion, and thus, we have used only the first three components for calculating the weights. Moreover, these three principal components account for 93.26% of cumulative variance of the variables, and their selection is legitimate and adequate. Subsequently, factorial axes were rotated using varimax rotation for the orthogonal of these factors and also to obtain a clear pattern of loading. The result of rotated factor loadings is presented in Table 3.

After factor rotation, the next step is to calculate the weights from the factor loadings. The weights are obtained by squaring each of the factor loadings representing the proportion of the total unit variance of the indicator explained by the factors.Footnote 7 The result is reported in Table 4.

From Table 4, the first intermediate composite includes EYS (weight 0.090), MYS (weight 0.091), LEX (weight 0.091), IMR (weight 0.090), ISF (weight 0.091), IWF (weight 0.089), NEG (weight 0.091), FRT (weight 0.089), CO2 (weight 0.088) and VAA (weight 0.053). The second intermediate includes REG (weight 0.452) and ROL (weight 0.443). The final intermediate composite includes INF (weight 0.481) and GCF (weight 0.466). We observe that the renewable energy REG takes a significantly higher weight when compared to other variables. This is not surprising as renewable energy sources, and its consumption is important for the sustainably of development. An interesting observation is that the variables in the societal component have more or less equal weights. This could possibly point toward collective importance of all the variables as each of them is means and ends to each other in the development process. Economic component comprising of GDP, INF and GCF has higher weight, and this is understandable considering the role of economic performance of countries in determining the development process. In terms of individual weights, ROL is also among those variables having substantial significance. As explained earlier, rule of law is also an essential feature of sustainable development goals.

After the determination of the individual weights, the three intermediate composites are aggregated by assigning weight in accordance with the proportion of the explained variation. For instance, the first intermediate composite we have 0.778 (= 10.89/(10.89 + 1.65 + 1.45)), 0.118 for second and 0.102 for the third. The final weights obtained through PCA after the aggregation are given in Table 5.

Finally, the normalized variables \( z_{ti}^{(j)} \) are given weights accordingly and the board based development index is calculated for each of the country using the following formula:

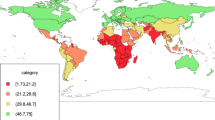

where \( {\text{BBDI}}_{t}^{(j)} \) is the broad-based development index for the jth country at time period t. BBDI for the 102 countries from 1996 through 2015 is presented in Appendix Table 6. The value of BBDI falls between zero and one, where values closer to one indicate higher development. A general observation is that barring few specific years, all the countries have shown improvement in the development process since 1995 through 2015.

As per the index based on the average rankings, we note that Norway stands first, followed by Switzerland in the second position and Spain taking the third position. Our results are quite different from the rankings based on GDP or HDI. This is not surprising as BBDI is intended to capture development beyond the scope of the traditional measures. It is worth reiterating that over and above economic performance, development process of a country should reflect in various factors such as better health, educational facilities, improvised living conditions, good governance, clean environment, etc., that can lead to sustainable well-being. For example, Norway on an average has close to 99% of its population having access to clean drinking water and sanitation facilities. Further, the percentage of renewable energy consumption in the total energy consumption for Norway is found to be 58%, whereas the world average stands well below at 28%. Moreover, they also have very low infant mortality rate at about 3 and an excellent educational record reflected in high-expected schooling rates for about 17 years. The life expectancy stands very high at 82 years in Norway, and Switzerland standing second in BBDI has 81 years. Switzerland also has high levels of expected years of schooling, low mortality rate, universal access to water, better sanitation, low rates of inflation, relatively low carbon emissions, better levels of freedom and rule of law. At this stage, in a preliminary comparison with the HDI, we note that countries like Norway, Switzerland, Spain, Slovenia, Singapore, Croatia, UK, France, Thailand, Italy and Netherlands leading BBDI have also performed well in HDI. However, for the want of brevity and to contain within scope of the current study, we shall not go further into comparison of ranks and features of the listed countries. This could be taken up as exercise for the future studies.

Summary and conclusions

Development is a broad-based concept involving various factors that could contribute to well-being of a nation in terms of various components such as human life, economy, society, environment and so on. However, while measuring the development process, most of the studies have limited its scope to GDP and related variables. This is clearly inadequate to measure the various aspects involved in the development process. Keeping this in mind, we have constructed a broad-based development index (BBDI) measuring development through its components, namely society, sustainability, economy and institutions. The sample for our study covers from 1996 through 2015 for 102 countries.

Societal aspect comprises of education, health, access to water and sanitation facilities, where education is measured in terms of expected year of schooling and mean year of schooling. Life expectancy and infant mortality rate capturing health and finally access to water and sanitation facilities are measured as percentage of population having access to improved water and sanitation facilities. Sustainability is measured in terms of energy use and environment. Energy use is captured through non-renewable and renewable energy consumption, whereas forest cover and CO2 emission account for state of environment. Economy stands for standard of living captured through real per capita GDP, rate of inflation and rate of investment. Finally, the state of institutions and governance is measured in terms of rule of law and voice and accountability. The rationales for selection of the variables are primarily based on its importance in the development process and also on availability of uniform data across the chosen countries. It could be noted that in all cases, the chosen variables are either means or end result of the development process. These variables are then weighted and aggregated to BBDI for each of the 102 countries. For the calculation of weights, we have opted for data-driven weights through PCA analysis. The results are in tune with our expectation, where the use of renewable resources indicating sustainability is having significantly higher weight among the variables. It is indeed beyond doubt that with increasing population and limited resources, the use of renewable is the key for development to be sustainable.

Notes

Sen (1983).

Detailed official report on calculation of HDI can be obtained from the United Nations Development Programme, Human Development reports at http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-index-hdi.

Can be accessed from WHO/Millennium Development Goals https://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/about/en/.

Can be accessed from UNDP/Sustainable Development Goals https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/sustainable-development-goals.html.

Human development Report, UNDP (2016).

Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicator methodology and user guide, OECD 2008.

References

Ansar A, Flyvbjerg B, Budzier A, Lunn D (2016) Does infrastructure investment lead to economic growth or economic fragility? Evidence from China. Oxford Rev Econ Policy 32(3):360–390

Arntzen A, Andersen AMN (2004) Social determinants for infant mortality in the Nordic countries, 1980–2001. Scand J Public Health 32(5):381–389

Berg LA, Desai D (2013) Background paper: overview on the rule of law and sustainable development for the global dialogue on rule of law and the post-2015 development agenda. UNDP, Paris

Bloom DE, Canning D (2009) Population health and economic growth. Health and growth. Working paper no. 24. World Bank

Bloom DE, Canning D, Jamison DT (2004) Health, wealth, and welfare. Finance Dev 41:10–15

Booysen F (2002) An overview and evaluation of composite indices of development. Soc Indic Res 59(2):115–151

Brundtland G, Khalid M, Agnelli S, Al-Athel S, Chidzero B, Fadika L Singh M (1987) Our common future (\’brundtland report\’)

Chiswick BR, Cohen Y, Zach T (1997) The labor market status of immigrants: effects of the unemployment rate at arrival and duration of residence. Ind Labor Relat Rev 52(2):289–303

Costanza R, Hart M, Posner S, Talberth J (2009) Beyond GDP: the need for new measures of progress. Pardee Working Paper no.4. Boston University, Boston

Decancq K, Lugo MA (2009) Weights in multidimensional indices of wellbeing: an overview. Econom Rev 32(1):7–34

Desai M (1991) Human development: concepts and measurement. Eur Econ Rev 35(1):350–357

Drewnowski J, Scott W (1966) The level of living. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, Report No. 4. Geneva

German Development Cooperation in Energy Sector (2014) Sustainable energy for development. Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ)

Ginsberg N, Osborn J, Blank G (1986) Geographic perspectives on the wealth of nations. Department of Geography Research Paper No. 220, University of Chicago, Chicago, pp. 17–120

Goetz AM, Jenkins R (2002) Voice, accountability and human development: the emergence of a new agenda. UNDP: occasional paper, human development report

Goossens Y, Mäkipää A et al (2007) Alternative progress indicators to gross domestic product (GDP) as a means towards sustainable development. European Parliament, Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy, Brussels

Greco S, Ehrgott M, Figueira J (2016) Multiple criteria decision analysis, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Greco S, Ishizaka A, Matarazzo B, Torrisi G (2017) Stochastic multi-attribute acceptability analysis (SMAA): an application to the ranking of Italian regions. Reg Stud 52(4):585–600

Greco S, Ishizaka A, Tasiou M, Torrisi G (2018) On the methodological framework of composite indices: a review of the issues of weighting, aggregation, and robustness. Soc Indic Res 141(1):61–94

Grupp H, Mogee ME (2004) Indicators for national science and technology policy: How robust are composite indicators? Res Policy 33(9):1373–1384

Grupp H, Schubert T (2010) Review and new evidence on composite innovation indicators for evaluating national performance. Res Policy 39(1):67–78

Guptha KSK, Rao RP (2018) The causal relationship between financial development and economic growth: an experience with BRICS economies. J Soc Econ Dev 20(2):308–326

Hicks N, Streeten P (1979) Indicators of development: the search for a basic needs yardstick. World Dev 7(6):567–580

Hutcheson GD, Sofroniou N (1999) The multivariate social scientist: an introduction to generalized linear models. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Johnson RA, Wichern DW (1999) Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39:31–36

Lai D (2003) Principal component analysis on human development indicators of China. Soc Indic Res 61(3):319–330

Lind N (2004) Values reflected in the human development index. Soc Indic Res 66(3):283–293

Lindelow M (2006) Sometimes more equal than others: how health inequalities depend on the choice of welfare indicator. Health Econ 15(3):263–279

Lucas RE Jr (1988) On the mechanics of economic development. J Monetary Econ 22(1):3–42

Mazziotta M, Pareto A (2012) A non-compensatory approach for the measurement of the quality of life. Quality of life in Italy. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 27–40

McGranahan DV, Richard-Proust C, Sovani NV, Subramanian M (1972) Contents and measurement of socioeconomic development. A staff study of the United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD), Praeger, New York, pp 3–136

Michaelson J, Abdallah S, Steuer N, Thompson S, Marks N (2009) National accounts of well-being: bringing real wealth onto the balance sheet. New Economics Foundation, London

Morris MD (1979) Measuring the condition of the world’s poor: the physical quality of life index. Pergamon Policy Studies No. 42, pp 20–56

Morris MD, Liser FB (1980) The PQLI: measuring progress in meeting human needs. Overseas Development Council, Communique on Development Issues No. 32

Myrdal G (1957) Rich lands and poor. Harper and Row, New York

Noorbakhsh F (1996) The human development indices: Are they redundant? Occasional papers no. 20. Centre for Development Studies, University of Glasgow, Glasgow

Noorbaksh F (1998) A modified human development index. World Dev 26(3):517–528

North D (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

OECD (2008) Handbook on constructing composite indicators: methodology and user guide. OECD Publishing, Paris

Pearson K (1901) On lines and planes of closest fit to systems of points in space. Philos Mag Ser 6 2(11):559–572

Perthel D (1981) Laws of development, indicators of development, and their effects on economic growth. Doctoral Thesis, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, pp 6–7

Ram R (1982) Composite indices of physical quality of life, basic needs fulfilment, and income. A ‘principal component’ representation. J Dev Econ 11(2):227–247

Rao VVB (1991) Human development report 1990: review and assessment. World Dev 19(10):1451–1460

Ravallion M (1997) Good and bad growth: the human development reports. World Dev 25(5):631–638

Rawls J (1971) A theory of justice. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Ray AK (2008) Measurement of social development: an international comparison. Soc Indic Res 86(1):1–46

Rostow WW (1959) The stages of economic growth. Econ History Rev 12(1):1–16

Saaty RW (1987) The analytic hierarchy process: what it is and how it is used. Mathematical Modelling 9(3–5):161–176

Saisana M, Saltelli A, Tarantola S (2005) Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis techniques as tools for the quality assessment of composite indicators. J R Stat Soc Ser A Stat Soc 168(2):307–323

Santos ME, Santos G (2014) Composite indices of development. In: Currie-Alder B, Kanbur R, Malone D, Medhora R (eds) International development: ideas, experience and prospects. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 133–150

Schepelmann P, Goossens Y, Makipaa A (2010) Towards sustainable development: alternatives to GDP for measuring progress. (No. 42). Wuppertal Spezial

Sen A (1983) Development which way now? Econ J 93(372):745–762

Sen A (1998) Development as freedom. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Sen A (2006) What is the role of legal and judicial reform in the development process? World Bank Legal Rev 2(1):21–42

Solow RM (1956) A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Q J Econ 70(1):65–94

Srinivasan TN (1994) Human development: a new paradigm or reinvention of the wheel? Am Econ Rev Pap Proc 84(2):238–243

Stiglitz JE (2015) Inequality and economic growth. Polit Q 86(S1):134–155

Stiglitz J, Sen AK, Fitoussi JP (2009) The measurement of economic performance and social progress revisited: reflections and overview. OFCE working paper. Columbia University, New York, NY

Streeten P (1995) Human development: the debate about the index. Int Soc Sci J 47(143):25–37

Todaro MP (1989) Economic development in the third world, 4th edn. Longman, New York

Todaro MP, Smith SC (2011) Economic development, 11th edn. Pearson Education Limited, Essex

UNDP (2016) Human development report: online database. United Nations Development Programme, Brussels. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/data. Accessed 12 Jan 2019

UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2013) Data centre. http://stats.uis.unesco.org. Accessed Nov 2013

Wilkinson RG, Pickett KE, De Vogli R (2010) Equality, sustainability, and quality of life. BMJ 341:c5816

World Bank (1991) The World Bank annual report 1991. Washington, DC. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/262711468313513741/The-World-Bank-annual-report-1991. Accessed 20 Aug 2019

World Bank (2012) New directions in justice reform. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/928641468338516754/pdf/706400REPLACEM0Justice0Reform0Final.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2019

World Health Organization (2007) Active ageing: a policy framework. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2002/WHO_NMH_NPH_02.8.pdf. Accessed 25 Aug 2019

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions that helped to improve the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Basel, S., Gopakumar, K.U. & Rao, R.P. Broad-based index for measurement of development. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 22, 182–206 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00093-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-020-00093-2

Keywords

- Measurement of development

- Broad-based development index

- Principal component analysis

- Sustainable development