Abstract

Introduction

The cooperative breeding framework suggests that help from extended family members with childrearing is important adaptation for our species survival, and it is universal. However, the degree of alloparental help may vary between societies, families, and over time. We hypothesized that maternal and paternal effort, as well as alloparental care, would depend both upon resource availability (SES) and different mating opportunities for males and females in three countries: Brazil, Russia, and the USA.

Methods

We analyzed the intergenerational interactions between family members during childcare via Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in R-software. Online samples were collected from Brazil (N = 538), Russia (N = 502), and the USA (N = 308).

Results and Discussion

The results of our study are consistent with previous research on life history (LHT) plasticity, which has shown a negative correlation between the perceived childhood SES and perceived parental effort. However, our models indicated a possible cultural difference in the estimates of poverty paths: in Brazilian and American samples, SES had a greater impact on paternal care than on maternal, while in Russia, poverty had a greater effect on mothers’ effort. This reversed effect size on maternal versus paternal effort in Russia may suggest that Russian mothers experience a trade-off between working outside the home and direct childcare, while Russian fathers may adopt a “faster” LHT strategy as they are the limited sex in the mating pool.

Our findings also demonstrate that the parental effort of both parents was positively associated, indicating their mutualistic relationship. We also found that according to the recollections of respondents’ maternal grandparents usually compensate the lack of paternal effort, but their help, as well as the help of paternal grandparents, was indifferent to the poverty cues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In comparison to our closest living relatives, chimpanzees, human parent–offspring bonds are quite distinctive with respect to several life-history traits (Hrdy & Burkart, 2022). In humans, children are weaned at a younger age, reach sexual maturity later, and are more than twice as likely to survive to reproductive age (Hill, 1993; Kaplan et al., 2000). Human juveniles are also subsidized by their parents for much of their growth and development. In addition, human reproductive rates are relatively fast, with mothers having birth intervals of only 2–3 years. This is in contrast to most great apes, which have much longer birth intervals of 4–8 years (Kaplan et al., 2000; Kennedy, 1993). Shorter interbirth intervals and longer post-weaning dependency create an environment in which human mothers often raise children of various ages concurrently. Raising dependents at different developmental stages simultaneously presents a unique challenge to human mothers because different offspring require varying time and energy investments. In addition, these costs are disproportionately high due to our larger brains and delayed onset of maturity (Gould, 1977; Leigh, 2004; Somel et al., 2009). Despite the fact that relative to men, women have provided the bulk of parental care (Hames, 1988; Hurtado et al., 1985, 1992; Kramer & Russell, 2015; Marlowe, 2003), mothers practically never raise children alone in any traditional human social system (Mace, 2018). Even in the nuclear family mothers are rarely self-sufficient, with helpers playing a significant role in childrearing across different cultures (Kramer & Russell, 2015; Sear, 2017). While overall help with childrearing from extended family members is universal, exactly who helps may vary between societies, families, and over time, depending on who is willing and available to help (Sear, 2017). But typically, mothers rely on help from close genetic relatives, such as their children’s grandparents (Hawkes & Coxworth, 2013), or on the assistance of older children, usually daughters (Kaplan et al., 2009). Typically, mothers also depend on help from their male partners (Kramer, 2010; Mace, 2018).

Despite sharing similar genetic interests in the survival and success of offspring, their optimal strategies for achieving this goal may differ (Gowaty & Hubbell, 2009). According to sexual conflict theory, differences in optimal parental investment can lead to conflict between the sexes (Lessells, 2006; Lessells & McNamara, 2012). The core of this conflict lies in the proportion of care each parent provides to their joint offspring (Lessells, 2006). If one parent invests more heavily in care than the other, their fitness may be reduced relative to the other parent. The result of this conflict is that a parent's fitness may be maximized by the other parent providing a larger share of care than that parent is expected to give. For instance, females would benefit if their mate invested more energy into childcare and less into mating with other females (Kokko & Jennions, 2008, 2014). This would increase the chances of offspring survival and ultimately, the female's reproductive success, because the energy invested in intrasexual males’ competition for additional sexual partners could be better spent caring for common offspring (Kokko & Jennions, 2012; Lessells, 2006). However, this strategy may not be in the best interest of the male, who may want the female to invest most or even solely in caring for their offspring. This would allow him to conserve enough energy for additional mating and various somatic tasks, contributing to the development of his physical achievements. It is supposed that differences in these optimal parental investments can lead to a tug-of-war between the sexes, with each parent trying to shift the balance of care in his/her own favor: the more effort one parent puts into raising their current offspring, the more energy the other parent can potentially allocate towards their own somatic and mating activities, and vice versa. However, the opportunities for realizing reproductive goals can vary greatly in different societies, where distinct social and economic structures, as well as population dynamics can significantly alter possible reproductive optima for both parents (Gowaty & Hubbell, 2009; Grosjean & Brooks, 2017; Kokko & Jennions, 2012, 2014; Loo et al., 2017; Marlowe, 2000; Schacht & Borgerhoff Mulder, 2015; Schacht et al., 2016; Uggla & Mace, 2017; Yong & Li, 2022).

Older siblings are also significant caregivers. Yet this is a frequently neglected source of assistance for mothers (Kramer, 2002; Weisner et al., 1977). While children’s help varies according to specific subsistence ecologies, in traditional societies, elder siblings provide various economic activities. They also play a role in raising their younger siblings by protecting family young, thereby they may potentially enhance the mother's fertility or improve sibling condition (Nitsch et al., 2013). Studies from several populations have shown that the presence of older siblings can positively effect on survival of younger children in a family (Crognier et al., 2001; Nitsch et al., 2013, 2014; Sear & Mace, 2008).

The family's locus may also substantially impact alloparents investment. Many modern Western societies demonstrate flexible residence norms; couples can live independently from both sides of their kin, and households consisting only of nuclear families are common (Kramer & Russell, 2015). However, traditionally, three generations typically live together, though this may take a variety of different forms (Sear, 2017). Anthropologists' observations of the family structure of such an extended three-generational family have shown that mothers often reduce the time spent on household chores, and grandmothers take on these auxiliary activities (Hawkes et al., 1997, 1998; Hurtado et al., 1992; Leonetti & Nath, 2005). However, matrilineal and patrilineal grandparents have different degrees of confidence in the genetic relationship of their grandchildren. Mathematical models utilize the concept of paternity uncertainty as an adaptive explanation for bias in paternal and patrilineal relatives' investments, as proposed by Kurland in 1979 and further supported by Perry and Daly in 2017. And based on ethnographic descriptions, willingness to invest in offspring has been strongly associated with certainty of genetic relatedness between helper and child, with respect to both fathers and other male relatives (Alvergne et al., 2010; Cabeza de Baca et al., 2014; Fox et al., 2010; Leonetti & Nath, 2005; Perry & Daly, 2017; Sear et al., 2000; Voland & Beise, 2002). Based on ethnographic descriptions, in polygynous societies where paternity is uncertain fathers invest little, and women are mostly indifferent to male investment and prefer the winners of male–male competition, an indicator of higher male genetic quality (Marlowe, 2000). In that case maternal kin assistance could potentially substitute for the shortage of paternal help, as previous anthropological investigations in traditional societies have suggested that matrilineal kin help can serve as an alternative to paternal help (Fouts, 2008; Mace, 2018; Sear & Mace, 2008). The positive impact of matrilineal grandmother assistance on the reproductive success of their daughters has been shown both in traditional societies, as well as in Western industrialized countries (Tanskanen & Rotkirch, 2014).

It is widely recognized that parental investment plays a crucial role in mediating the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and child developmental outcomes (Guo & Harris, 2000). According to life history theory (LHT), parents with low socioeconomic status may face a trade-off between working outside the home and spending time with their children, resulting in less direct care and more parental effort associated with indirect care, such as children and family provisioning (Bereczkei et al., 2004; Brumbach et al., 2009; Dinh et al., 2022; Ellis & Essex, 2007; Figueredo & Jacobs, 2010; Frankenhuis & Nettle, 2020). Resource deficiency may mediate this relationship, with working parents providing less effort due to limited time and energy. In harsh and unpredictable environments, parents also may redirect their limited resources into fitness-maximizing activities, such as various somatic tasks or mating efforts (Ellis & Essex, 2007; Figueredo & Wolf, 2009; Hehman & Salmon, 2019; Mogilski et al., 2020). From this perspective, in families with lower socioeconomic status, a present–future reproductive trade-off is expected to be resolved in favor of early reproduction, accompanied by relatively low levels of parental effort and a generally higher total fertility rate (Cabeza de Baca & Ellis, 2017; Hehman & Salmon, 2019). In resource scarce and unpredictable environments accelerating maturation and increasing family size give “fast” individuals greater fitness benefits, even if it sometimes compromises important somatic tasks (Belsky, 2012). At the same time, the fast reproductive strategy entails a fundamental LHT trade-off between offspring number (quantity) and offspring fitness (quality) and having more children in low SES families means less and less potential resources to invest in each child as the number of children increases. In this manner, natural selection shapes investment per offspring as well as offspring number (Gowaty & Hubbell, 2009; Kaplan et al., 2009).

Current Research Design

Anthropological and comparative studies have shown that help from kin may be facultative to some extent, depending on factors, including the mother's ability to rear children, the presence of other kin, the number of older siblings, the availability of resources, the degree of genetic relatedness, and genetic certainty (Hrdy, 2009). In this study, we aimed to explore the dynamics of helping behavior among key alloparent agents by utilizing a comparative, cross-cultural approach. We explored parental-kinship investments in childrearing in three major postindustrial nations: Brazil, Russia, and the United States. In addition to covering vast land areas, they are also similar in terms of population size and pace of urbanization (The World Fact Book, 2020a, b). Our approach overcomes Galton's problem by gathering data from three different countries, as the examined countries do not belong to the same region and have not undergone similar development, so analyses of the data obtained from different continents will not violate the assumption of independent sampling (Pollet et al., 2017).

Our study focuses primarily on parental effort, particularly conflict resolution between mothers and fathers, within the context of interfamilial helping interactions. In this study, data were collected on the perceived childhood SES and perceived amount of parental and grandparental care of the participants. It was hypothesized that maternal and paternal effort would be affected by both the perceived resources of the family (socioeconomic status) and the perceived availability of grandparents' help and sibling support. The causal relationships among family members will be modeled in three samples using structural equation modeling (SEM), a powerful statistical method that can be used to model observational and experimental data.

In constructing a family model(s), we assume a number of causal connections:

-

1.

By applying parental conflict theory, we model the relationship between maternal and paternal effort, assuming a shortage of paternal effort results in greater maternal effort.

-

2.

In future models we propose several paths directed at maternal grandparents, as maternal grandparents used to be the main assistant for mothers in case other family members' help was not sufficient.

-

3.

As predicted by LHT, exogenous factors such as poverty should negatively affect parental efforts, both for mothers and for fathers.

-

4.

At the same time, resource deficiency should be positively associated with grandparental help. As a result, we are modeling two paths from poverty to grandparental assistance.

-

5.

Based on LHT, family poverty also should be positively associated with sibling number and vice versa. Thus, in the current study, we predict that there is a two-sided association between the number of older siblings and poverty.

Methods

Samples

Brazil

Data from Brazil was collected online (from 20 March to 9 June 2019) from college students at two different public universities: University of São Paulo and Federal University of Espírito Santo, both in states in southeastern Brazil. Compensation was not provided.

Russia

Data from the Russian sample was collected online via the social network service VK, via publishing advertisement on online page of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (from 5 March to 28 Aprel 2019). Approximately half of the data was collected in campus dormitories in The Russian State University for the Humanities by distributing paper version of the Questionnaire, data collected from 05 February 2017 to 20 April 2017. Compensation was not provided.

United States of America

The United States data were collected online from college students at two universities, one in Arizona (from 9 to 16 September 2019) and the other in California (15 March to 25 March 2019). Participants were compensated with course credit.

Because the initial age of the USA sample was lower than in the other two samples, since the American subjects were students, it was decided to exclude respondents over 40 years of age from all samples. Thus, 67 responses from the Brazilian sample, 118 responses from the Russian sample, and 2 from the American sample were excluded.

Table 1 displays the sample sizes and key demographics of each of these samples.

Measures

Grandparental Availability (Semenova, 2017)

This scale consists of six manifest variables resulting in two higher-order constructs (“maternal kin availability”, 3 items, and “paternal kin availability”, 3 items). Grandparents contact frequency were used as proxies for support (Emmott & Mace, 2015). Sample items include: “During my childhood, my grandparents on my mother's side lived: with us; separately, but in the same city; in another city, but no more than 3 h from us; in another city, more than 3 h’ drive from us; In another country; I mostly lived with my grandparents and not my parents?”; “How often did you spend your school holiday with your grandparent on your father's side?”; “How often did your grandparents on your mother's side babysit with you when you were ill?”. The resulting Cronbach’s alphas (α) were 0.71 (US 0.74, BR 0.72, RU 0.70) for matrilineal grandparental availability, and 0.69 (Appendix B: US 0.71, BR 0.75, RU 0.66) for paternal grandparental availability.

Subscales Parental Efforts

This scale consisted of a modified version of the Early Environment Questionnaire (Black, 2016) and the RGGU Family Ethology Questionnaire (Semenova, 2017). A heatmap of the loading strength within 10- item Scale of Mother\Father behavior allowed for extraction of two factors for each scale (Appendix A). To maintain our a priori research interest of evaluating the degree of parental direct care and effort (practical and emotional support associated with parent’s time and energy budgets) we excluded items concerning instability in parenting style. All items were tested using Factor and Exploratory analysis; graphical results presented in Appendix A. Therefore, each latent construct (Maternal and Parental effort) consists of 4 items: “Rate the amount of care and love that your father gave you on a scale from 0 (none at all) to 6 (very caring and loving)”; “My father usually helped me solve problems”; “My father let me learn from my own mistakes”; “I felt that my mother was emotionally supportive”.

Aggregated items were z-transformed and in the end, a high internal consistency level was obtained. The α for maternal effort was 0.86 (US 0.93, BR 0.91, RU 0.90). For paternal effort, the α was 0.89 (US 0.90, BR 0.88, RU 0.89). Each scale had a significant amount of shared variance (Appendix B).

Childhood Resource Deficiency

A modified version of the EEQ was also used to assess family socioeconomic status. A heatmap of the loading strength within 10- item allowed for extraction of two factors. Only 5 items were selected for the latent construct that serves to represent a Deficiency in bioenergetic and material resources. All items passed through Factor and Exploratory analysis (Appendix A). Meanwhile the scope of items concerning parental indirect investments were excluded. Sample questions include: “My family was never able to ‘get ahead’ financially”; “My family seemed to live paycheck to paycheck when I was growing up” (Appendix A). The α for the “Poverty” subscale was 0.82 (US 0.85, BR 0.79, RU 0.82; Appendix B).

Older Siblings

According to Kramer (2010), in traditional societies, older siblings can play a significant role in assisting their mothers. Their presence in a family can serve as a proxy for their ability to assist with young children. To determine the number of older siblings in a family, this study used the participants' birth order, subtracting one.

Statistical Analyses

Both the SEMs (Grace, 2008; Grace et al., 2010) and the Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) were performed using R (“Lavaan” package, Rosseel, 2012). Using IBM SPSS-Statistic program software, the Cronbach’s alphas and the covariance matrices of the subscales were computed (Appendix B).

Results

The Structural Model

We conducted Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to investigate interaction between (allo)parents (mothers, fathers, grandmothers, and grandfathers) as well as the impact of poverty and the number of older siblings on childrearing.

Path models were fit using maximum likelihood methods to allow inclusion of all observed data for those participants who provided incomplete data. After fitting the full model, paths for which p ≥ 0.05 were sequentially removed to obtain the reduced valid model. The modified model was found to have adequate fit, Model χ2 was 5078.334, df = 190, p -value (Chi-square) < 0.001. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.064 [0.058, 0.070], P-value RMSEA < 0.001; with Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.93; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.91. R-Square estimates: Moth.Care = 0.184, Fath.Care = 0.220, Moth.Gp = 0.068, Fath.Gp = 0.058. A summary of the numerical results from the analysis of the model could be found in Appendix C.

A manifested variable (questionary item) was omitted in Fig. 1, and only latent constructs were included in the SEM (Fig. 1; to simplify the figures, we emphasized regression paths only and introduced ready-made latent constructs calculated in advance as CFAs) except for the parameters “Older Siblings”. All solid pathways shown in Fig. 1 are statistically significant, dashed pathways are non-significant.

Unconstrained SEM. Green arrows denote positive relationships, and red arrows negative ones, dashed pathways are non-significant. The thickness of the significant paths has been scaled based on the magnitude of the standardized regression coefficient. The dotted line indicates paths that are not statistically significant

Multi-Sample SEMs

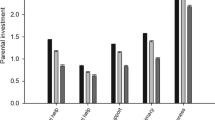

Multi-sample SEMs are normally applied to the comparison of two or more independent samples to assess whether path estimates of the measurement model are invariant across groups. The standardized unconstrained model for each sample is presented in Fig. 2. The SEMs were found to have adequate fit, model χ2 = 5530.12; Degrees of freedom = 57; p-value (Chi-square) < 0.001; Test statistic for Brazil = 311.59; for Russia = 275.058; Test statistic for USA = 296.47. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.068 [0.061; 0.075]; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.92; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.90. Output from the multi-sample SEMs analysis presented in Appendix C. Results show that in each group the path estimates are in the expected direction and indicated many similarities in structural relationships to the final model.

In Fig. 2, pathways between studied latent variables were represented in the three SEMs.

Each group's path’s estimates show many similarities in structural relationships to the first model (Fig. 1), except for a negative correlation between "Older Siblings" and parental efforts in the USA sample.

In all samples, we observed a negative association between the poverty factor and parental effort, whereas associations between poverty and grandparental effort were not significant in multi-sample SEMs except for the Russian sample, in which maternal grandparental assistance was negatively correlated with low socioeconomic status. In all three samples, the relationship between the father's effort and the maternal grandparents was negative, but only in the Brazilian sample was this pathway significant. The number of older siblings was negatively associated with maternal care in the American sample, whereas in the Russian sample, that path was positive and had a notably higher value but was not significant. Further GLM analyses of SEMs parameters enabled us to estimate the degrees of cross-cultural consistency of each effect within the model (Appendix D).

By comparing the main cultural effects of poverty, we demonstrated the negative predictive reliance of perceived family SES to paternal care in the three different samples (t -value = -8.596; p ( >|t|) = < 2e-16), however, in the Russian sample, the association between paternal care and poverty was smaller (t -value = 2.625; p ( >|t|) = 0.008) in comparison to Brazil, where family poverty factor had a significant negative impact on paternal effort. The general level of family poverty was found to decrease maternal efforts much more in the Russian sample (Estimate size = -0.42; t-value = -4.582; p ( >|t|) < 0.001), compared to the Brazilian sample, where maternal care had a weak non-significant association with the general family level of poverty. In the US sample, maternal care is less associated with paternal care (t-value = -2.718; p ( >|t|) = 0.006). Interestingly, the US sample displayed higher scores in paternal care in comparison to the other two cultures overall (Intercept = 0.382; t-value = -2.718; p ( >|t|) = < 0.001). In the US matrilineal grandparental effort had significantly higher association with patrilineal grandparental effort in comparison to the Brazilian sample. The effect of birth order parameter was significantly lower in Russia (t -value = -9.027;p ( >|t|) < 0.001). Respondents in the Brazilian sample reported the highest levels of poverty during their childhood compared to other samples (compare to the US: t –value = -5.94; p ( >|t|) < 0.001; compare to Russia: t -value = -6.56; p ( >|t|) < 0.001).

Discussion

Evolutionary ecological principles provide a framework to both test and elucidate a plethora of phenomena pertaining to our reproductive and (allo) parenting behavior and their adaptation benefits. In this study we utilized SEMs to examine parental and alloparental effort provided by family members in three distinct countries: Brazil, Russia, and the USA, while facing poverty-induced pressure. For that reason, we collected data on the perceived childhood SES of the participants as well as their perception of the amount of parental care and grandparent care. Our key findings align with prior LHT research theory that demonstrates a negative association between harsh and unpredictable environments and parental effort (Figueredo & Jacobs, 2010; Figueredo et al., 2020; Giosan & Wyka, 2009; Gladden et al., 2013; Hurst & Kavanagh, 2017; Pelham, 2019; Seidl-de-Moura et al., 2013). We found that the anticipated increase in the cost of parenting in the perceived poverty-stricken environments led to a decrease in the perceived parental effort by both mothers and fathers, resulting in negative estimated values for the corresponding SEMs paths. Results of the current study also show that paternal care was more negatively affected by poverty than maternal care (see Fig. 1). This finding demonstrated that under poverty-induced stress, males potentially adopt a "fast" life-history strategy, channeling their limited resources towards activities that maximize their fitness, such as intrasexual competition and mating efforts. This, of course, reduces their investment in a child.

According to Brazil and the US data, it is evident that financial concerns have a significant impact on paternal involvement compared to the data from Russia. This discovery suggests that in wealthy Brazilian and US families, both parents share comparable responsibilities of raising their child, whereas in impoverished families, the mother bears the primary burden of care. Alternatively, the distinct negative effect of poverty on paternal care could be explained by traditional gender roles, whereby a greater emphasis is placed on fathers to be providers (Kaplan et al., 2009; Marlowe, 2000, 2003). As a result, when families face financial difficulties, fathers may prioritize their role as providers over their role as caregivers, redirecting their time and energy towards indirect forms of care. This evolutionary predisposition towards male provisioning may explain the larger effect size of perceived poverty level on fathers' reactions to economic stress within the family.

It is important to note that the effect size of perceived poverty on paternal care varied across the samples studied. These discrepancies suggest that mechanisms for allocating childcare could respond flexibly to resource deficiency (see Fig. 2). For instance, among the samples studied, respondents in Russia remember maternal care as being more sensitive to the cues of poverty. This finding raises important questions about the factors that may contribute to the sex-specific impact of poverty on parental behavior. One potential explanation lies in sexual conflict theory, which predicts that due to the skewed sex ratio observed in the Russian sample (Bhattacharya, 2015; The World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2019a, b), there may be a decrease in male parental effort, as males are the minority within the mating pool. Russian males have broader opportunities on the mating market, potentially redirecting their energy into mating effort and not matching the level of their own effort with investment made by other family members. Therefore, it is possible that Russian males may have a reduced focus on childcare due to having more extensive mating prospects and a potentially limited timeframe to pursue them (The World Bank, World Development Indicators, 2019a, b). Such a shortage of paternal help implies that mothers with low SES may experience a trade-off between working outside of the home and the time involved with childcare. And potentially the absence of paternal help may lower females’ reproductive productivity. In families where mothers face a dilemma between direct and indirect forms of caring, maternal grandparents’ step in to compensate for the lack of paternal involvement. Our models show that there is a negative correlation between maternal grandparents and paternal effort in the general model and in all studied samples, however in Russia and the US this relationship was not significant. Potentially, the lack of paternal effort within families triggers the availability of matrilineal support, and vice versa (see Yong & Li, 2022).

On the other hand, Structural Equation Models (SEMs) results do not support the conflicting dyadic mechanism of maternal versus paternal effort. Our results demonstrate that in these three populations, perceived parental efforts are intertwined and positively associated with each other. This could be attributed to the fact that, since the beginning of human evolution, pair-bonding and parental collaboration have been oriented as adaptations to fulfill the needs of increasingly altricial offspring (Chapais, 2011; Lovejoy, 1981, 2009; Raghanti et al., 2018). Although cultural variations should be taken into consideration. Particularly, in the United States, the effect size of the pathway from paternal to maternal care was relatively small. However, it is noteworthy that American fathers exhibit exceptionally high levels of reported paternal care, which lends support to one of our LHT hypotheses suggesting that superior socioeconomic conditions in the American families we investigated in this pilot study may lead to greater parental investment in comparison to their Brazilian and Russian counterparts.

In line with LHT predictions, our findings also revealed that, on average, participants who reported lower SES also reported the presence of a higher number of older siblings in their families. This result could have two different interpretations, which are compatible. One possible explanation is that larger numbers of dependent children may strain a family’s financial capacities, especially in Western societies where parents tend to invest considerable financial resources into their offspring’s well-being. Having more offspring results in a diminishing pool of potential resources to invest in each child. This association may be especially relevant for paternal effort in the US sample, as we found a negative association between parents' effort and the number of older siblings in the family (Figure 4 and Appendix D). However, the association between parental effort and siblings’ number could be more complex. Individuals exposed to a high level of socioeconomic deprivation could follow a “fast” life-history strategy, which is associated with a relatively high fertility rate. In this regard, the positive association between number of older siblings’, perceived poverty and low parental effort is in line with the LHT prediction stating that harsh environments increase individual reproductive rates and simultaneously diminish investment in each child when mortality is high, or resources are limited. At the same time Russian SEM could be an exemption from that LHT prediction, as Russian data showed that having a higher number of older siblings led to sufficient increased maternal care (however this path was not significant, with estimate value = 0.272; z-value = 1.686; P( >|z|) = 0.092). This finding potentially indicates the leading role that in Russia older children have in helping their mothers, which is comparable to the involvement of Russian fathers in parenting (Estimate = 0.240; z-value = 2.839; P( >|z|) = 0.005). Based on these results, we can suppose that mothers in larger Russian families are more attentive to their children, either because their older children provide them with full-fledged assistance or because the former are more oriented towards ample motherhood.

Families with low perceived SES did not necessarily demonstrate greater grandparental involvement; the direct paths between poverty and grandparental help were not significant, except for the Russian SEM, where this pathway was significant. However, the association between family poverty and maternal grandparents’ assistance in this case was negative. This finding does not support our hypothesis about grandparents' role in families under financial stress or in need of support (see Livingston & Parker, 2010). Potentially, in low SES families, grandparents may work and do not have time for childcare. Another possible explanation could be that older individuals may suffer from poor health and may not have the resources to offer investment to grandchildren. To understand the complex relationship between grandparent’ help and family SES, additional research is needed.

Additionally, the results of our study uncovered a positive pathway between perceived paternal grandparental care and perceived maternal grandparents’ care. It is possible that firstborn children used to benefit from the attention and involvement of grandparents from both sides of the family, who are youthful and highly engaged in care. However, it is also possible that children who were born later may not receive the same level of support since their grandparents are too old for helping or they have already passed away. This hypothesis could be supported by data from Brazilian and Russian SEM models in which the number of older siblings used to negatively correlate with grandparents' help. Hence, this association may be simply a matter of timing of birth order and consequential grandparents’ aging. Another factor that could contribute to this connection is the proximity of grandparents to their grandchildren. Nevertheless, the questions regarding the proximity of grandparents from the paternal and maternal sides of the family, as well as the age of grandparents at the time of their death, were not within the scope of this study and should be explored in future research.

Limitations

The authors declare the differences in sampling methods between the three countries. In the USA and Brazil, respondents were recruited exclusively from student environments, while in Russia, half of the answers were collected from volunteers through the social network (Vkontakte). The authors suggest a certain bias in the answers among samples: for instance, in the US and Brazil the questionnaire was presented to students’ groups, whilst in Russia, subjects responded to advertisements on social networks, and they may have had certain experiences that prompted them to participate in a particular study about family and parental effort. The authors acknowledge that differences in collection methods may have affected the results.

The study has another serious limitation because most of the manifested items implemented in SEMs were collected and identified based solely on subjective psychological factors – perceived (allo) parental effort and perceived social status; this limits our ability to draw theoretical conclusions.

The relatively high RMSEA value obtained in SEM and MSEM may be attributed to the intended simplification of the present SEM, wherein only a single LHT variable — resource deficiency — was considered; meanwhile, there appears to be no one-size-fits-all answer to the complex structure of kinship help. Future studies should include other LHT relevant factors that are theoretically predicted to play a role, such as parent–child resemblance, particularly paternal resemblance, which might influence paternal care on the part of the father and his kin.

Conclusion

In this study, utilizing SEM, we investigated family members’ provision of parental and alloparental effort in different cultural contexts, particularly when impacted by poverty. Within the structural models, the perceived parental effort of both parents in all samples was significant and positive, indicating that their relationships are complementary and mutualistic rather than antagonistic.

We also found a robust overall negative impact of perceived poverty on parental effort. The results of our study are consistent with previous studies in LHT plasticity, which reveal a negative correlation between harsh environment/resource deficiency, and parental effort. At the same time, our results demonstrated that paternal care was more negatively affected by poverty than maternal care, as reported in the general SEM. Considering the cross-cultural comparative SEMs analyses and the lack of invariance detected in the SEMs intercepts, this study represents robust evidence of systematic cultural differences. Results of our study offer valuable insights into the influence of poverty on parental care, highlighting the contrast in the impact of poverty on maternal versus paternal effort in Russia, compared to the other samples, where the effect size of poverty was greater for mothers than for fathers. It may also indicate an effect of sex-ratio on LHT strategy such that males may be pursuing a faster strategy when they are scarcer sex. As a result, Russian mothers may face a difficult trade-off between pursuing employment outside of the home and dedicating time to their children, given the shortage of paternal support.

Data Availability

The data is available on link: https://app.flourish.studio/visualisation/6444982/edit?

References

Alvergne, A., Faurie, C., & Raymond, M. (2010). Are parents’ perceptions of offspring facial resemblance consistent with actual resemblance? Effects on parental investment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(1), 7–15.

Belsky, J. (2012). The development of human reproductive strategies: Progress and prospects. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 310–316.

Bereczkei, T., Gyuris, P., & Weisfeld, G. E. (2004). Sexual imprinting in human mate choice. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(1544), 1129–1134.

Bhattacharya, P. C. (2015). Gender balance and economic outcomes in Russia, India, and China. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Black, C. J. (2016). The life history narrative: How early events and psychological processes relate to biodemographic measures of life history. The University of Arizona.

Brumbach, B. H., Figueredo, A. J., & Ellis, B. J. (2009). Effects of harsh and unpredictable environments in adolescence on development of life history strategies. Human Nature, 20(1), 25–51.

Cabeza De Baca, T., Sotomayor-Peterson, M., Smith-Castro, V., & Figueredo, A. J. (2014). Contributions of matrilineal and patrilineal kin alloparental effort to the development of life history strategies and patriarchal values: A cross-cultural life history approach. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(4), 534–554.

Cabeza De Baca, T., & Ellis, B. J. (2017). Early stress, parental motivation, and reproductive decision-making: Applications of life history theory to parental behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 15, 1–6.

Chapais, B. (2011). The evolutionary history of pair-bonding and parental collaboration. In C. Salmon, T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of evolutionary family psychology (pp. 1-33). Oxford University Press 33.

Crognier, E., Baali, A., & Hilali, M. K. (2001). Do “helpers at the nest” increase their parents’ reproductive success? American Journal of Human Biology: The Official Journal of the Human Biology Association, 13(3), 365–373.

Dinh, T., Haselton, M. G., & Gangestad, S. W. (2022). “Fast” women? The effects of childhood environments on women’s developmental timing, mating strategies, and reproductive outcomes. Evolution and Human Behavior, 43(2), 133–146.

Ellis, B. J., & Essex, M. J. (2007). Family environments, adrenarche, and sexual maturation: A longitudinal test of a life history model. Child Development, 78(6), 1799–1817.

Emmott, E. H., & Mace, R. (2015). Practical support from fathers and grandmothers is associated with lower levels of breastfeeding in the UK millennium cohort study. PLoS ONE, 10(7), e0133547.

Figueredo, A. J., & Jacobs, W. J. (2010). Aggression, risk‐taking, and alter‐ native life history strategies: The behavioral ecology of social devi‐ ance. In M. Frias‐Armenta & V. Corral‐Verdugo (Eds.), Bio‐psycho‐so‐ cial perspectives on interpersonal violence (pp. 3–28). Hauppauge, NY: NOVA Science Publishers

Figueredo, A. J., & Wolf, P. S. A. (2009). Assortative pairing and life history strategy: A cross-cultural study. Human Nature, 20, 317–330.

Figueredo, A. J., Black, C. J., Patch, E. A., Heym, N., Ferreira, J. H. B. P., Varella, M. A. C., ... & Fernandes, H. B. F. (2020). The cascade of chaos: From early adversity to interpersonal aggression. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 15(3), 231.

Fouts, H. N. (2008). Father involvement with young children among the Aka and Bofi foragers. Cross-Cultural Research, 42(3), 290–312.

Fox, M., Sear, R., Beise, J., Ragsdale, G., Voland, E., & Knapp, L. A. (2010). Grandma plays favourites: X-chromosome relatedness and sex-specific childhood mortality. Proceedings of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 277(1681), 567–573.

Frankenhuis, W. E., & Nettle, D. (2020). The strengths of people in poverty. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(1), 16–21, 0963721419881154.

Giosan, C., & Wyka, K. (2009). Is a successful high-K fitness strategy associated with better mental health? Evolutionary Psychology, 7(1), 147470490900700100.

Gladden, P. R., Figueredo, A. J., Andrejzak, D. J., Jones, D. N., & Smith-Castro, V. (2013). Reproductive strategy and sexual conflict slow life history strategy inihibts negative androcentrism. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 4(1), 48–71.

Gould, S. J. (1977). Ontogeny and Phylogeny. Harvard Univ Press.

Gowaty, P. A., & Hubbell, S. P. (2009). Reproductive decisions under ecological constraints: It’s about time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(Supplement 1), 10017–10024.

Grace, J. B. (2008). Structural equation modeling for observational studies. The Journal of Wildlife Management, 72(1), 14–22.

Grace, J. B., Anderson, T. M., Olff, H., & Scheiner, S. M. (2010). On the specification of structural equation models for ecological systems. Ecological Monographs, 80(1), 67–87.

Grosjean, P., & Brooks, R. C. (2017). Persistent effect of sex ratios on relationship quality and life satisfaction. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 372(1729), 20160315.

Guo, G., & Harris, K. M. (2000). The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children’s intellectual development. Demography, 37(4), 431–447.

Hames, R. B. (1988). The allocation of parental care among the Ye'kwana. University of Nebraska.

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J. F., & Blurton Jones, N. G. (1997). Hadza women’s time allocation, offspring provisioning, and the evolution of long postmenopausal life spans. Current Anthropology, 38(4), 551–577.

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J. F., Jones, N. B., Alvarez, H., & Charnov, E. L. (1998). Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(3), 1336–1339.

Hawkes, K., & Coxworth, J. E. (2013). Grandmothers and the evolution of human longevity: A review of findings and future directions. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 22(6), 294–302.

Hehman, J. A., & Salmon, C. A. (2019). Sex-specific developmental effects of father absence on casual sexual behavior and life history strategy. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5(1), 121–130.

Hill, K. (1993). Life history theory and evolutionary anthropology. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 2(3), 78–88.

Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and others. Harvard University Press.

Hrdy, S. B., & Burkart, J. M. (2022). How Reliance on Allomaternal Care Shapes Primate Development With Special Reference to the Genus Homo. In H. L. Sybil, D. F. Bjorklund (Eds.), Evolutionary Perspectives on Infancy (pp. 161–188). Cham: Springer.

Hurst, J. E., & Kavanagh, P. S. (2017). Life history strategies and psychopathology: The faster the life strategies, the more symptoms of psychopathology. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(1), 1–8.

Hurtado, A. M., Hawkes, K., Hill, K., & Kaplan, H. (1985). Female subsistence strategies among Ache hunter-gatherers of eastern Paraguay. Human Ecology, 13(1), 1–28.

Hurtado, A. M., Hill, K., Hurtado, I., & Kaplan, H. (1992). Trade-offs between female food acquisition and child care among Hiwi and Ache foragers. Human Nature, 3(3), 185–216.

Kaplan, H. S., Hooper, P. L., & Gurven, M. (2009). The evolutionary and ecological roots of human social organization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 364(1533), 3289–3299.

Kaplan, H., Hill, K., Lancaster, J., & Hurtado, A. M. (2000). A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence, and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 9(4), 156–185.

Kennedy, K. I. (1993). Fertility, sexuality and contraception during lactation. In J. Riordan, K. G. Auerbach (Eds.), Breastfeeding and Human Lactation (pp. 429–457). Boston, Mass: Jones and Bartlett.

Kokko, H., & Jennions, M. D. (2008). Parental investment, sexual selection and sex ratios. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 21(4), 919–948.

Kokko, H., & Jennions, M. D. (2012). Sex differences in parental care. In N. J. Role, P. T. Smiseth, & M. Kolliker (Eds.), The evolution of parental care (pp. 101–118). Oxford University Press.

Kokko, H., & Jennions, M. D. (2014). The relationship between sexual selection and sexual conflict. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 6(9), a017517.

Kramer, K. L. (2002). Variation in juvenile dependence: Helping behavior among Maya children. Human Nature, 13, 299–325.

Kramer, K. L. (2010). Cooperative breeding and its significance to the demographic success of humans. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 417–436.

Kramer, K. L., & Russell, A. F. (2015). Was monogamy a key step on the Hominin road? Reevaluating the monogamy hypothesis in the evolution of cooperative breeding. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews, 24(2), 73–83.

Kurland J. (1979). Paternity, mother’s brother, and human sociality. In N.A. Chagnon, W. Irons (Eds), Evolutionary biology and human social behavior. An anthropological perspective (pp. 145 – 180). Duxbury Press.

Leigh, S. R. (2004). Brain growth, life history, and cognition in primate and human evolution. American Journal of Primatology: Official Journal of the American Society of Primatologists, 62(3), 139–164.

Leonetti, D. L., & Nath, D. C. (2005). Kinship Organization and the Impact of Grandmothers on Reproductive Success among the Matrilineal Khasi and Patrilineal Bengali of Northeast India. Grandmotherhood: The evolutionary significance of the second half of female life, Rutgers University Press, 194.

Lessells, C. K. M. (2006). The evolutionary outcome of sexual conflict. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 361(1466), 301–317.

Lessells, C. M., & McNamara, J. M. (2012). Sexual conflict over parental investment in repeated bouts: Negotiation reduces overall care. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1733), 1506–1514.

Livingston, G., & Parker, K. (2010). Since the start of the great recession, more children raised by grandparents. Pew Research Center’s, Social & Demographic Trends Project, 6.

Loo, S. L., Hawkes, K., & Kim, P. S. (2017). Evolution of male strategies with sex-ratio–dependent pay-offs: Connecting pair bonds with grandmothering. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1729), 20170041.

Lovejoy, C. O. (1981). The origin of man. Science, 211(4480), 341–350.

Lovejoy, C. O. (2009). Reexamining human origins in light of Ardipithecus ramidus. Science, 326(5949), 74–74e8.

Mace, R. (2018). Kinship (Human), evolutionary and biosocial approaches to. In H. Callan (Ed.), The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology (pp. 1–7). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published.

Marlowe, F. (2000). Paternal investment and the human mating system. Behavioural Processes, 51(1–3), 45–61.

Marlowe, F. W. (2003). A critical period for provisioning by Hadza men: Implications for pair bonding. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24(3), 217–229.

Mogilski, J. K., Mitchell, V. E., Reeve, S. D., Donaldson, S. H., Nicolas, S. C. A., & Welling, L. L. M. (2020). Life history and multi-partner mating: A novel explanation for moral stigma against consensual nonmonogamy. Frontiers in Psychology, Section Evolutionary Psychology, 10, 3033.

Nitsch, A., Faurie, C., & Lummaa, V. (2013). Are elder siblings helpers or competitors? Antagonistic fitness effects of sibling interactions in humans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 280(1750), 20122313.

Nitsch, A., Faurie, C., & Lummaa, V. (2014). Alloparenting in humans: Fitness consequences of aunts and uncles on survival in historical Finland. Behavioral Ecology, 25(2), 424–433.

Pelham, B. (2019). Life history and the cultural evolution of parenting: Pathogens, mortality, and birth across the globe. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000185

Perry, G., & Daly, M. (2017). A model explaining the matrilateral bias in alloparental investment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(35), 9290–9295.

Pollet, T. V., Stoevenbelt, A. H., & Kuppens, T. (2017). The potential pitfalls of studying adult sex ratios at aggregate levels in humans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 372(1729), 20160317.

Raghanti, M. A., Edler, M. K., Stephenson, A. R., Munger, E. L., Jacobs, B., Hof, P. R., ... & Lovejoy, C. O. (2018). A neurochemical hypothesis for the origin of hominids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(6), E1108-E1116.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more. Version 0.5–12 (BETA). Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36.

Schacht, R., & Borgerhoff Mulder, M. (2015). Sex ratio effects on reproductive strategies in humans. Royal Society Open Science, 2(1), 140402.

Schacht, R., Tharp, D., & Smith, K. R. (2016). Marriage markets and male mating effort: Violence and crime are elevated where men are rare. Human Nature, 27(4), 489–500.

Sear, R. (2017). Family and fertility: Does kin help influence women’s fertility, and how does this vary worldwide? Population Horizons, 14(1), 18–34.

Sear, R., & Mace, R. (2008). Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evolution and Human Behavior, 29(1), 1–18.

Sear, R., Mace, R., & McGregor, I. A. (2000). Maternal grandmothers improve nutritional status and survival of children in rural Gambia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 267(1453), 1641–1647.

Seidl-de-Moura, M. L., de Carvalho, R. V. C., & Vieira, M. L. (2013). Brazilian mothers’ cultural models: Socialization for autonomy and relatedness. In M. L. Seidl-de-Moura (Ed.), Parenting in South American and African contexts (pp. 1–15). InechOpen.

Semenova, O. V. (2017). A kin family effort: a Russian example [Rodstvenny vklad: Rossiyskaya specifica]. Master's Theses at Russian state university for the humanities.

Somel, M., Franz, H., Yan, Z., Lorenc, A., Guo, S., Giger, T., ... & Khaitovich, P. (2009). Transcriptional neoteny in the human brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(14), 5743–5748.

Tanskanen, A. O., & Rotkirch, A. (2014). The impact of grandparental investment on mothers’ fertility intentions in four European countries. Demographic research, 31, 1–26.

The World Bank, World Development Indicators. (2019a). Mortality rate, adult, male (per 1,000 male adults) [Data file]. Accessed 2 Aug 2023. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.AMRT.MA

The World Bank, World Development Indicators (2019b). Survival to age 65, male (% of cohort) [Data file]. Accessed 2 Aug 2023. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TO65.MA.ZS

The World Fact Book (2020a). Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency [Data file]. Retrieved from –The World Factbook, area (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/area). Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

The World Fact Book (2020b). Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency [Data file]. Retrieved from – The World Factbook, demographic estimates (https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/population). Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

Uggla, C., & Mace, R. (2017). Adult sex ratio and social status predict mating and parenting strategies in Northern Ireland. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society b: Biological Sciences, 372(1729), 20160318.

Voland, E., & Beise, J. (2002). Opposite effects of maternal and paternal grandmothers on infant survival in historical Krummhörn. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 52(6), 435–443.

Weisner, T. S., Gallimore, R., Bacon, M. K., Barry III, H., Bell, C., Novaes, S. C., ... & Williams, T. R. (1977). My brother's keeper: Child and sibling caretaking [and comments and reply]. Current anthropology, 18(2), 169–190.

Yong, J. C., & Li, N. P. (2022). Elucidating evolutionary principles with the traditional Mosuo: Adaptive benefits and origins of matriliny and “walking marriages.” Culture and Evolution, 19(1), 22–40.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Russian Science Foundation № 24–28-01639, https://rscf.ru/project/24-28-01639/(only OS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design as well as in material preparation, data collection and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. The study protocol was approved by the University of Redlands Institutional Review Board (01/23/2019).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Participants included in the study did not provide their images, names, exact dates of birth, identity numbers, biometrical characteristics (such as facial features, fingerprint, writing style, voice pattern, DNA or another distinguishing characteristic). All research participants received unique subject IDs that do not identify them by as individuals to ensure anonymity.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A Exploring Subscale’s

Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10

Appendix B – The Measurement Models

Cronbach’s alphas and part-whole correlations (unit-weighted factor loadings) for the indicators with their respective unit-weighted factor scales in the United States of America (US), Brazil (BR), Russia.

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6

Appendix C The Numerical Results from the Analysis of the Model

Table 3

SEMs. Results for the Structural Equations Models

Model χ2 = 5530.115; Degrees of freedom = 570; P-value (Chi-square) < 0.001; Test statistic for Brazil = 311.591; for Russia = 275.058; Test statistic for USA = 296.466. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.068 [0.061; 0.075]; Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.919; Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.904

Appendix D Cross-cultural consistency of each effect within the model

The general lineal model (GLM) analyses of the degrees of cross-cultural consistency for regression pathways and their interactions in the model upon the three sites sampled (in the United States of America (US), Brazil (BR), Russia (RU)

Baseline of calculated GLM models represented by a Brazilians parameter set. Paths for which p ≥ .05 were removed from the Table 3.

Table 7

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Semenova, O., Figueredo, A.J., Tokumaru, R.S. et al. Evolutionary Adaptation Perspectives on Childcare with References to Life History Plasticity in the Modern World: Brazil, Russia, and the USA. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 10, 148–181 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-024-00241-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-024-00241-6