Abstract

Purpose of review

Chronic diarrhoea, defined as loose and more frequent motions continuing for longer than 4 weeks, is a common presenting symptom in infants and children. While this can be the presentation of a significant underlying disease process, it can also be benign or self-resolving. This review serves to highlight the range of conditions that can manifest with chronic diarrhoea, while emphasising approaches to assessment and management.

Recent findings

Increasing recognition of chronic diarrhoea in the context of immunodeficiency, especially those that feature gut inflammation, has changed the approach and management of these conditions. Similarly, the understanding of the aetiology and pathogenesis of various types of congenital diarrhoea (typically presenting in infancy with severe course) have advanced in recent years along with new genetic discoveries, leading to new approaches. New management options are also being considered for conditions such as antibiotic-associated diarrhoea and lymphangiectasia.

Summary

Increasing recognition of the role of critical factors such as diet, genetic risks, and disruptions to the intestinal microbiota has resulted in exciting new approaches to some of the conditions that can present with chronic diarrhoea in childhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic diarrhoea is a common symptom affecting children of all ages and in all parts of the world [1, 2]. Typical causes of chronic diarrhoea in infants include infections, post-infectious conditions, and food allergy: more significant causes could include immunodeficiency, post-antibiotic diarrhoea, and inflammatory conditions. Less concerning causes of chronic diarrhoea in older children include constipation with overflow and chronic non-specific diarrhoea. More concerning causes in older children include coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease.

This article aims to outline common and less common causes of chronic diarrhoea in children, with emphasis upon assessment and approach to the condition, and especially to existing and novel therapeutic options.

Chronic diarrhoea

Persistent diarrhoea is formally defined as a pattern of more frequent and less formed stools continuing for more than 2-week duration, while chronic diarrhoea defined as symptoms for 4 weeks [1, 2]. This common presenting symptom in infants and children can reflect significant underlying pathology, but many causes are benign or self-resolving.

Diarrhoea can reflect events in various places in the gastrointestinal tract, but most typically in the small intestine or colon. Various processes can generate diarrhoea—these include malabsorption, increased secretion, loss of gut length, or loss of mucosal function.

While some processes can occur in any age group, some patterns of chronic diarrhoea are more common in infancy and others more common in older children (Table 1). In addition, various pathogenetic mechanisms can lead to chronic diarrhoea; these include malabsorption and inflammation. Further, different mechanisms can lead to diarrhoea: osmotic, secretory, or mixed. A typical example of osmotic diarrhoea would be lactose intolerance, whereby the unabsorbed lactose generates an osmotic effect in the distal gut. Secretory diarrhoea can be secondary to an acquired (especially infectious) or congenital cause whereby increased intestinal secretions are produced. Coeliac disease is a typical example of mixed diarrhoea.

When evaluating a child with chronic diarrhoea, there are several key features on history or examination that can suggest a more significant pathology. These include failure to thrive (or weight loss), disruption to linear growth, blood present in stool (haematochezia), associated abdominal or perianal pain, associated dehydration (or episodes requiring rehydration), and the presence of clubbing or peripheral oedema on examination. The presence of one or more of these “red flag” features should alert the physician to undertake investigations and management.

This manuscript reviews the typical and most relevant patterns of chronic diarrhoea in these age groupings and outlines key associated features that are important in elucidating the importance of presenting symptoms. Furthermore, some relevant current and emerging management approaches are outlined.

Chronic diarrhoea in infancy

Several significant conditions can present in infancy with chronic diarrhoea. These include immunodeficiency, allergy, infection, and post-infectious enteropathy. Several of these conditions will be considered here.

Infection and post-infectious enteropathy

Many infectious agents can cause diarrhoea in infants and children. While most will cause a pattern of self-resolving diarrhoea over a few days, some are associated with chronic diarrhoea [3]. Giardia and Yersinia are examples.

Giardiasis reflects parasitic infestation of the small bowel, typically resulting from ingestion of contaminated water [4,5,6]. This condition can result in short and more prolonged diarrhoea, with repeated exposures also evident. Stool testing is utilised most commonly: serological testing may be available in some locations. Duodenal biopsies may also demonstrate characteristic histologic findings. Standard treatment for giardiasis is metronidazole (5 mg/kg/dose, with three doses daily for 7–10 days). Tinidazole (as a single dose) and nitazoxanide (daily dosing for 3 days) are alternatives. Treatment refractory giardiasis likely requires infectious disease consultation, but described options include quinacrine or combination therapies.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a food-borne pathogen that may lead to short- and long-term symptoms, including chronic diarrhoea [7, 8]. Numerous outbreaks related to various foods (such as salad items) are described. Untreated water, zoonotic infection from infected animals, or direct contact from an infected individual are all described also. Yersiniosis can be confirmed by specific stool culture (some laboratories will not routinely test unless requested) and serological tests. Management is generally supportive. Persistent or troublesome yersiniosis can be treated with antibiotic therapy (such as fluoroquinolone or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole).

Post-infectious enteropathy is characterised by persistent small bowel mucosal damage with delayed recovery, commonly resulting in chronic diarrhoea and consequent failure to thrive [9, 10]. This entity is more commonly seen in infancy with particular risk factors of young age, underlying poor nutrition, recurrent infection, or concurrent food protein intolerance. This entity could be diagnosed with small bowel biopsies obtained endoscopically, but may be empirically managed with nutritional support and consideration of hypo-allergenic formulae. There are limited data to support probiotics having a beneficial role [10••].

Congenital diarrhoea

A number of conditions can lead to onset of diarrhoea early in childhood with significant morbidity and impact. These can be characterised as abnormalities of transport in epithelial cells, disorder epithelial enzyme or metabolism, disorders of epithelial trafficking or orientation, and disorders of enteroendocrine cell function. In addition, disorders of immunoregulation can also present with early onset or chronic diarrhoea. A recent review provided a clear overview and approach to these conditions [11••].

Allergy

Several food protein allergy syndromes mediated by delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (not by direct IgE mechanisms) can present with chronic diarrhoea [12]. Allergic enteropathy, leading to small intestinal mucosal damage and reduction in absorptive surface, might present with failure to thrive with malabsorptive features (abdominal distension, iron or vitamin deficiencies). After exclusion of infectious causes, and after review of other history and family history, an empiric change to a hypoallergenic formula would be expected to resolve the diarrhoea.

Food-induced protocolitis typically presents in early infancy with chronic haematochezia along with more frequent loose motions [12]. This entity appears to be more common in breast-fed babies. It is important to exclude infection, coagulopathy, and local causes (e.g. fissures). Again, in a typical scenario, withdrawal of the trigger food antigen (most commonly but not exclusively cow’s milk) in the infant’s diet would lead to resolution of the bloody diarrhoea. On occasion, a change to a hypoallergenic formula and/or proctoscopy may be required.

Immunodeficiency

Altered defence mechanisms in the form of various paediatric immunodeficiency diseases (PID) or syndromes can present with chronic diarrhoea. In a group of 246 Taiwanese children with various PID, 21 presented with chronic diarrhoea [13]. Many of the children with chronic diarrhoea had troublesome courses and were associated with increased mortality. In another cohort of 425 children PID from Turkey, 195 had gastrointestinal manifestations (this included chronic diarrhoea in 112 of the 195 children) [14].

In a number of the children in both these case series, the findings included endoscopic and histologic changes resembling inflammatory bowel disease. These monogenic forms of gut inflammation reflecting underlying immunodeficiency are increasingly recognised. Collectively termed the very-early onset IBD, an appropriate work-up includes screening for standard PID, followed by detailed focused genetic studies to elucidate the underlying causation [15••].

Chronic diarrhoea in older children

Examples of important organic diseases presenting with chronic diarrhoea in older children include coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Functional conditions, such as irritable bowel syndrome, can also present in this fashion. Infections and post-infectious enteropathy can also occur in older children (similar infections to infants but post-infectious enteropathy less frequent). Less concerning causes include constipation with associated overflow.

Coeliac disease

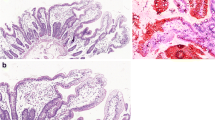

Coeliac disease is a chronic incurable condition associated with villous atrophy in the small bowel [16]. Triggered by gluten in a child with at risk genetic profile, immune responses lead to an inflammatory change in the small bowel characterised by villous atrophy, crypt hyperplasia, and intraepithelial lymphocytosis. Although classically, the presentation of coeliac disease is of malabsorption (including diarrhoea, failure to thrive, low levels of micronutrients, and abdominal distention), it is now clear that children can present with a wide range of gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal symptoms. In a large New Zealand patient cohort, 38.9% of 222 children presenting with GI symptoms reported diarrhoea [17].

The management of coeliac disease requires a lifelong gluten-free diet. Generally, children respond well to GFD with up to 70–80% having normalisation of small bowel mucosa by 12 months after diagnosis [18, 19]. Various novel therapies are being assessed that include peptidases (to digest gluten intraluminally), gluten binders, and drugs that augment intestinal barrier function [20]. While much work has focused on the potential of the Nexvax2 therapeutic vaccine, the future of this intervention is unclear as a phase 2 clinical trial was recently ceased prematurely [21].

Inflammatory bowel disease

The inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are a group of conditions characterised by active and chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract [22]. Crohn disease (CD) features patchy inflammation that can be in any segment of the gut. The other main type is known as ulcerative colitis (UC) which typically involves continuous inflammation extending for a variable distance from the rectum around the colon, without involvement elsewhere. Some children are initially labelled as IBD unclassified (IBD-U), when there are features of IBD without clear findings that definitively label as CD or UC.

Diarrhoea is a typical feature of CD, along with abdominal pain and weight loss, while bloody diarrhoea is seen more often in UC. Symptoms, such as diarrhoea, may extend for many months before diagnosis is made, especially in children with CD [22].

The standard approach to possible diagnosis of IBD is to document that there are inflammatory changes present (serum and/or faecal markers), while excluding other causes, such as infection and coeliac disease. If serum inflammatory markers (e.g. C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or platelets) or faecal markers (e.g. stool calprotectin) are altered in the appropriate clinical setting, endoscopic assessment is required for definitive diagnosis (endoscopic and histologic findings).

Management involves resolving active inflammation (inducing remission) followed by maintenance of remission. Exclusive enteral nutrition is recommended in many guidelines as the primary way to induce remission in childhood, due to high rates of remission, low side effects, and various additional benefits (superior mucosal healing, improved bone health, enhanced nutrition) [23]. Other medical and surgical therapies can be used to induce remission. Maintenance of remission may involve ongoing medical therapies, such as biologic agents (anti-tumour necrosis factor-α antibodies). Novel nutritional approaches being evaluated internationally include a whole-food based diet therapy and the CD exclusion diet [24•, 25•].

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a functional gut disorder, most commonly presents with diarrhoea, but can also feature constipation or alternating symptoms. IBS can be seen as a pattern of characteristic symptoms with exclusion of other causes such as infections, gut inflammation, and coeliac disease.

A low FODMAP diet (reflecting low levels of fermentable carbohydrates) is beneficial in a number of adults with IBS and is also helpful for children with IBS [26••, 27]. This dietary intervention, conducted under the supervision of a trained dietitian, involves the complete exclusion of FODMAPs for a 4–6-week period followed by a phased reintroduction of groups of carbohydrates. A recent retrospective study showed improvement in symptoms in 23 of 29 New Zealand children with IBS [28]. Thirteen of those with diarrhoea predominance had resolution of symptoms. Fructans were the most common carbohydrate that triggered symptoms in these children: apples were specifically mentioned by six children. Further paediatric studies of the short- and long-term impacts of fermentable carbohydrate exclusion are required.

Chronic non-specific diarrhoea

Also known as functional diarrhoea or toddler’s diarrhoea, chronic non-specific diarrhoea (CNSD) is a common but benign cause of chronic diarrhoea. Typically occurring in toddlers, but potentially starting in late infancy, CNSD is characterised by frequent loose bowel motions, but no disruption to growth patterns or general well-being. Symptoms usually improve by school age.

The Rome IV criteria define CNSD as being four or greater stools per day in a child aged between 6 and 60 months, with no disruption of growth, if adequate caloric intake is maintained [29]. The previous criterion of nocturnal stooling was not included.

The approach to this condition involves careful exclusion of significant underlying disease (such as coeliac disease or enteric infections). Various dietary factors may contribute to loose stools: these include excessive fruit juice, excessive fructose or sorbitol, and low-fat diet. Management typically involves reassurance and modification of diet as required [30].

Other patterns of chronic diarrhoea

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD) can occur in any age group, however may be more common in younger children (who may be given antibiotics more frequently). However, older children, particularly those who receive multiple courses of antibiotics for underlying health issues, may also develop AAD. This entity reflects an antibiotic-provoked disruption in the intestinal microbiota community. Early and profound changes in the diversity of the intestinal microbiota are well-demonstrated [31].

AAD typically commences during or after a course of antibiotics, especially broad-spectrum antibiotics. This may then lead to ongoing loose, frequent motions and delay the child’s return to normal activities (whether that be preschool or school) and impact adversely upon the family’s quality of life.

While overall changes in the patterns of the intestinal microbiota are well-described, AAD may also be related to overgrowth of specific organisms. A particular example of this is Clostridioides difficile. C. difficile infection (CDI) may be less likely in infancy (due to developmental lack of specific receptors for the toxin), but is overall of increasing relevance in children overall. Furthermore, rates of CDI are increasing dramatically in some areas of the world, with consequent dramatic increases in morbidity and mortality [32••, 33].

While primary prevention focusing on increased antibiotic stewardship is critical in decreasing the prescription of antibiotics in the first instance, clearly antibiotics are unavoidable in many cases. Several reports show that co-administration of a probiotic with the antibiotic can reduce the rates of AAD [34•]. In this case, the probiotic should be administered from the start of the antibiotic course and given at least 2 h separate to the antibiotic. There are no firm guidelines as to when to cease the probiotic course: an empiric approach is to continue for at least 1 week after the end of the antibiotics. Probiotics shown to have roles in reducing AAD include Saccharomyces boulardii and Lactobacillus rhamnosus [34•].

When concerned about CDI, stool testing should request specific testing for this organism and its related toxin. CDI can be managed in the first instance with fidaxomicin or vancomycin (or metronidazole if fidaxomicin is not available). Recurrent CDI can be managed initially with fidaxomicin (if vancomycin is given first), vancomycin (if initial treatment with metronidazole), or a tapering course of vancomycin [35,36,37, 38•]. The co-administration of S. boulardii may be helpful. Faecal microbial transplantation (FMT) has been shown to have extremely high efficacy for recurrent CDI in children and adults, especially for second or further recurrences [39•, 40]. However, a recent safety warning has been released by the Food and Drug Administration following two cases of transmission of a multi-drug-resistant organism following FMT [41]. Consequently, FMT for recurrent CDI should only be considered in a specialised centre under the confines of a clinical trial or within the guidance of an FMT specialist.

Pancreatic exocrine dysfunction

Pancreatic exocrine dysfunction can present with steatorrhoea, failure to thrive, and fat-soluble vitamin deficiency. Various aetiologies are recognised such as cystic fibrosis and Shwachman-Diamond syndrome [42, 43]. Diagnostic findings include low levels of faecal elastase (< 100 μg/g), along with fat-soluble vitamin deficiency. Key management principles include fat-soluble vitamin supplementation and pancreatic enzyme treatment, along with close dietary support and regular monitoring of growth. With adequate pancreatic enzyme treatment, diarrhoea would be expected to resolve.

Lymphangiectasia

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) can present at any age through childhood, with typical symptoms of diarrhoea, peripheral oedema, and poor growth [44]. Recurrent infections may also be seen. Although the exact aetiology of PIL is unclear, it reflects an underlying abnormality of intestinal lymphatics, such that lymph contents (particularly albumin, immunoglobulins, lymphocytes, long-chain triglycerides, and fat-soluble vitamins) are lost in the gut. Loss of fat impacts on growth and may generate steatorrhoea. Enteric protein loss leading to hypoalbuminaemia leads to reduced oncotic pressure and peripheral edema and potentially ascites, while hypogammaglobulinaemia and lymphopenia may increase the risk of infections.

Diagnosis is with characteristic biochemical pattern and demonstration of dilated small intestinal lymphatics histologically. Typical management involves an ultra-low-fat diet, supplemented with medium chain triglyceride predominant formulae and supplements. Albumin infusions may be required to augment oncotic pressure and relieve symptoms due to fluid accumulation. Although various other therapies have been considered, several recent case reports suggest promising outcomes with rapamycin inhibitors (e.g. everolimus) [44, 45•].

Other causes of chronic diarrhoea, including non-gastrointestinal causes

Diarrhoea is a very common side effect of medications given to children for various reasons. The excipients present in medications given for other reasons can also trigger loose motions; especially when multiple medications are being given in suspension forms. Careful review of the child’s history will be important in this entity, with consequent adjustment to the way the child’s medications are given if possible.

Furthermore, chronic diarrhoea can result from excessive use of stool softeners, other laxatives, or other agents. This can reflect self-administration or delivery by a parent or caregiver [46]. This so-called factitious diarrhoea can be difficult to ascertain and define. However, certain agents can be detected on specialised testing [47].

Other conditions in the abdomen could also lead to chronic diarrhoea. These include chronic urinary tract infection and various non-enteric infections (such as pneumonia, malaria, and others). Congenital abnormalities, such as malrotation with incomplete obstruction or blind loop syndrome, could also present with chronic diarrhoea.

Conclusions

Many conditions can present with prolonged diarrhoea in childhood. While a number of these can develop at any age, some are typically seen more in younger infancy while others are more commonly seen in older children. Conditions featuring chronic diarrhoea can lead to significant morbidity in children. Consequently, prompt recognition and early diagnosis are critical. New treatment approaches are available for some of these conditions, while others are emerging.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Schiller LR, Pardi DS, Sellin JH. Chronic diarrhea: diagnosis and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:182.

DuPont H. Persistent diarrhea: a clinical review. JAMA. 2016;315:2712–23.

Kaiser L, Surawicz CM. Infectious causes of chronic diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:563–71.

Einarsson E, Ma’ayeh S, Svärd SG. An up-date on Giardia and giardiasis. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;34:47–52.

Fink MY, Singer SM. The intersection of immune responses, microbiota, and pathogenesis in giardiasis. Trends Parasitol. 2017;33:901–13.

Leung AKC, Leung AAM, Wong AHC, Sergi CM, JKM K. Giardiasis: an overview. Recent Patents Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019;13:134–143.

Espenhain L, Riess M, Müller L, Colombe S, Ethelberg S, Litrup E, et al. Cross-border outbreak of Yersinia enterocolitica O3 associated with imported fresh spinach, Sweden and Denmark, March 2019. Euro Surveill. 2019;24(24).

Strydom H, Wang J, Paine S, Dyet K, Cullen K, Wright J. Evaluating sub-typing methods for pathogenic Yersinia enterocolitica to support outbreak investigations in New Zealand. Epidemiol Infect. 2019;147:e186.

Ochoa TJ, Salazar-Lindo E, Cleary TG. Management of children with infection-associated persistent diarrhea. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15:229.

Bernaola Aponte G, Bada Mancilla CA, Carreazo Pariasca NY, Rojas Galarza RA. Probiotics for treating persistent diarrhoea in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(11):CD007401 Systematic review evaluating probiotics for AAD.

•• Thiagarajah JR, Kamin DS, Acra S, Goldsmith JD, Roland JT, Lencer WI, et al. Advances in evaluation of chronic diarrhea in infants. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:2045–2059.e6 Clear and focused overview of these important conditions, emphasising pathogenesis, assessment, and management aspects.

Nowak-Węgrzyn A, Katz Y, Mehr SS, Koletzko S. Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:1114–24.

Lee WI, Chen CC, Jaing TH, Ou LS, Hsueh C, Huang JL. A nationwide study of severe and protracted diarrhoea in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3669.

Akkelle BS, Tutar E, Volkan B, Sengul OK, Ozen A, Celikel CA, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations in children with primary immunodeficiencies: single center: 12 years experience. Dig Dis. 2019;37:45–52.

•• Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, Shah N, Kammermeier J, Elkadri A, et al. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:990–1007.e3. Important review of VEO-IBD and investigation approach.

Lebwohl B, Sanders DS, Green PHR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 2018;391(10115):70–81.

Kho A, Whitehead M, Day AS. Coeliac disease in children in Christchurch, New Zealand: presentation and patterns from 2000-2010. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4:148–54.

Pekki H, Kurppa K, Mäki M, Huhtala H, Sievänen H, Laurila K, et al. Predictors and significance of incomplete mucosal recovery in celiac disease after 1 year on a gluten-free diet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1078–85.

Bannister EG, Cameron DJ, Ng J, Chow CW, Oliver MR, Alex G, et al. Can celiac serology alone be used as a marker of duodenal mucosal recovery in children with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet? Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1478–83.

Alhassan E, Yadav A, Kelly CP, Mukherjee R. Novel nondietary therapies for celiac disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;8:335–345. Overview of emerging therapies for celiac disease.

ImmusanT discontinues phase 2 clinical trial for Nexvax2® in patients with celiac disease. http://www.immusant.com/ImmusanT%20Nexvax2%20P2%20-%2025Jun19%20Final.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2019.

Lemberg DA, Day AS. Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis in children: an update for 2014. J Paediatr Child Health. 2015;51:266–70.

Critch J, Day AS, Otley A, King-Moore C, Teitelbaum JE, Shashidhar H, et al. Use of enteral nutrition for the control of intestinal inflammation in pediatric Crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:298–305.

• Levine A, Wine E, Assa A, Sigall Boneh R, Shaoul R, Kori M, et al. Crohn’s disease exclusion diet plus partial enteral nutrition induces sustained remission in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157:440–450.e8 First formal evaluation of this new treatment approach.

• Svolos V, Hansen R, Nichols B, Quince C, Ijaz UZ, Papadopoulou RT, et al. Treatment of active Crohn’s disease with an ordinary food-based diet that replicates exclusive enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology. 2019;156:1354–1367.e6. First report of this novel food-based approach to management.

•• Mitchell H, Porter J, Gibson PR, Barrett J, Garg M. Review article: implementation of a diet low in FODMAPs for patients with irritable bowel syndrome-directions for future research. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:124–39 Overview of low FODMAP diet approaches.

Chumpitazi BP, Cope JL, Hollister EB, Tsai CM, McMeans AR, Luna RA, et al. Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:418–27.

Brown SC, Whelan K, Gearry RB, Day AS. Low FODMAP diet in children and adolescents with functional bowel disorder: a clinical case note review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Open. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/jgh3.12231.

Benninga MA, Faure C, Hyman PE, St James Roberts I, Schechter NL, Nurko S. Childhood functional gastrointestinal disorders: neonate/toddler. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1443–55.e2.

Zeevenhooven J, Koppen IJ, Benninga MA. The new Rome IV criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants and toddlers. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2017;20:1–13.

Burdet C, Nguyen TT, Duval X, Ferreira S, Andremont A, Guedj J, et al. Impact of antibiotic gut exposure on the temporal changes in microbiome diversity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:e00820–19.

Noor A, Krilov LR. Clostridium difficile infection in children. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47:e359-e365. Abdullatif VN, Noymer A. Clostridium difficile infection: an emerging cause of death in the twenty-first century. Biodemography Soc biol. 2016;62:198-207. An outline of the rising impact of this pathogen.

Suárez-Bode L, Barrón R, Pérez JL, Mena A. Increasing prevalence of the epidemic ribotype 106 in healthcare facility-associated and community-associated Clostridioides difficile infection. Anaerobe. 2019;55:124–9.

Goldenberg JZ, Lytvyn L, Steurich J, Parkin P, Mahant S, Johnston BC. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(12):CD004827. Cochrane review of this topic.

Pai S, Aliyu SH, Enoch DA, Karas JA. Five years experience of Clostridium difficile infection in children at a UK tertiary hospital: proposed criteria for diagnosis and management. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51728.

Saha S, Khanna S. Management of Clostridioides difficile colitis: insights for the gastroenterologist. Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2019;12:1756284819847651.

Cammarota G, Gallo A, Ianiro G, Montalto M. Emerging drugs for the treatment of Clostridium difficile. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2019;24:17–28.

• Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478–98 North American guideline to treatment of this infection.

• Debast SB, Bauer MP, Kuijper EJ, European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases: update of the treatment guidance document for Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(Suppl 2):1–26 European guideline to treatment of this infection.

Chen B, Avinashi V, Dobson S. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent clostridium difficile infection in children. J Inf Secur. 2017;74(Suppl 1):S120–7.

https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/important-safety-alert-regarding-use-fecal-microbiota-transplantation-and-risk-serious-adverse. Accessed 13 Oct 2019.

Capurso G, Traini M, Piciucchi M, Signoretti M, Arcidiacono PG. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency: prevalence, diagnosis, and management. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2019;12:129–39.

Uc A, Fishman DS. Pancreatic disorders. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2017;64:685–706.

Von der Weid P-Y, Day AS. Pediatric lymphatic development and intestinal lymphangiectasia. In: Kuipers E, editor. Encyclopedia of gastroenterology. second ed: Elsevier; 2020;158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.66051-8.

• Ozeki M, Hori T, Kanda K, Kawamoto N, Ibuka T, Miyazaki T, et al. Everolimus for primary intestinal lymphangiectasia with protein-losing enteropathy. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152562 Report of clinical experience illustrating potential benefits of this novel therapy.

Abraham BP, Sellin JH. Drug-induced, factitious, & idiopathic diarrhoea. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:633–48.

Shelton JH, Santa Ana CA, Thompson DR, Emmett M, Fordtran JS. Factitious diarrhea induced by stimulant laxatives: accuracy of diagnosis by a clinical reference laboratory using thin layer chromatography. Clin Chem. 2007;53:85–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Day reports personal fees from Janssen, personal fees from Sanofi and personal fees from AbbVie.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Pediatric Gastroenterology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Day, A.S. Chronic Diarrhoea in Infants and Children: Approaching and Managing the Problem. Curr Treat Options Peds 6, 1–11 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-020-00187-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-020-00187-3