Opinion statement

Purpose of the review

Purpose of the review The goal of this article is to provide the reader an up-to-date overview of the role that health information technology (HIT) plays in modern-day healthcare quality improvement (QI) work and processes. The reader should be able to understand the unique benefits and challenges that HIT can impart on QI efforts, as well as calibrate their expectations appropriately. Examples will be grounded in recent informatics evidence and standard practices.

Recent findings

Recent findings Technology has been shown to an effective enabler and potentiator for quality improvement in initiatives and programs such as population health management, research, and QI networks, and minimizing use of unproven therapies (e.g., unindicated antibiotics), for example. HIT challenges remain that can limit this positive effect, including data management and quality issues, technical interoperability barriers, and the general nature of quality reporting as it exists today.

Summary

Summary Information technology in the form of electronic health records and other systems are ubiquitous and powerful enablers of quality improvement efforts in healthcare. When these digital tools are applied according to best practices and in an evidence-based manner, they can have profound impacts on both quality improvement processes and outcomes. Technology and the general healthcare environment are rapidly changing, though, and further study of the intersection of HIT and QI will continue to inform us of the real promise and pitfalls of this intersection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Information technology has long been seen as a powerful vehicle for improving the health and healthcare delivery system in the USA and internationally. Government-sponsored incentive plans such as the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act and Meaningful Use programs have made electronic health record (EHR) systems nearly ubiquitous [1, 2••, 3, 4]. Barriers to adoption in some areas and contexts, however, remain a challenge [5, 6]. The widespread adoption of electronic health record systems and other digital technologies, coupled with increasing national healthcare expenditures, has heightened expectations of many stakeholders, including policymakers, politicians, payors, and most importantly, healthcare consumers. A near-universal expectation of all parties is that EHRs will drive quality improvement (QI) in many aspects of care, ultimately leading to better health outcomes for patients, and do so at lower costs [7]. A well-known manifestation of this phenomenon is the Institute of Healthcare Improvement’s “IHI Triple Aim”, which consists of improving patient experience (including quality and satisfaction), improving population health, and reducing the per capita cost of care [8, 9].

EHRs have demonstrated the capability of improving patient safety in many aspects, although it is recognized that, on the whole, rates of iatrogenic harm in the USA are difficult to improve at scale [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Much work remains to be done in this area if large-scale gains are to be made. While improving patient safety is critical, it is but only one domain of quality improvement. Other current key concepts related to QI are population management, healthcare networks, and resource stewardship, among many others. In this article, we will begin with a brief overview of these initiatives and the role of HIT in promoting them, as well as discuss some of the challenges faced when using HIT for QI projects and programs. Finally, we will cover the role of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), a major funder and champion of the use of HIT in quality improvement work and provide resources for more information on the intersection between these two interest areas.

Key quality improvement concept domains, sample initiatives, and the information technology that supports them

Population health management

EHRs are well-positioned to assist care providers in managing the health of their patient populations. As the central platforms for data entry, storage, processing, and reporting, users of modern systems have capabilities at their disposal unlike any toolset previously available. As EHRs have matured, vendors have designed more advanced population health management functionalities into their products.

Perhaps the most fundamental and important of these tools are the patient registries, which define and contain the populations of interest or cohorts of patients being managed. Precise definitions of inclusion and exclusion criteria are paramount to the accuracy of the registries. Equally important is precise definition around the metrics or measures of interest that the cohort will be evaluated against. This evaluation allows providers and administrators to understand the aggregate health of their population of interest, benchmark their practice against exemplars, detect process, and outcome outliers (both favorable and unfavorable), and identify “care gaps” among their population, such as patients not up to date with preventative care measures (e.g., immunizations) [17]. Patients with chronic conditions are significant beneficiaries of these types of activities [18, 19•].

On the more advanced side, EHRs with registries are beginning to supply not only reporting functionalities, but more robust analytic engines and tools as well. This is case at both the local and national level, with some vendors supplying external benchmarking capabilities that allow institutions and care facilities to compare their performance and quality to other centers in an anonymous fashion. Data and statistical visualization tools permit users to quickly and automatically synthesize the information pertaining to their populations. Some systems will even allow providers and administrators effector mechanisms to automatically notify patients of the healthcare variance and mitigate the issue by scheduling follow-up visits, tests, and procedures.

Research and improvement networks

Somewhat related to population health management is the concept of research and improvement networks. In a quest to not “reinvent the wheel”, healthcare services researchers and federal sponsors have encouraged the utilization of healthcare networks to accomplish public health, research, and quality improvement goals. The philosophy and overarching theme of networks is to encourage coordinated activities that spread best practices and dissemination of knowledge at an accelerated pace. The information technology infrastructure of most networks also allows aggregation and sharing of data through federated systems which confer advantages such as universal institutional review boards (IRBs) which can expedite projects by removing site-specific approval for data access and study processes. PCORnet, the patient-centered outcomes research network, refers to this as their “Front Door”, and much has been published in the informatics literature about the IT infrastructure underlying the network [20,21,22,23,24]. Pediatric-specific networks and collaboratives have demonstrated particularly impressive improvements in clinical outcomes [18, 25, 26••].

The Solutions for Patient Safety (SPS) network is, as the name suggests, a network focused on safety, particularly hospital-acquired conditions. SPS has grown from an Ohio-based network to an international one [27, 28]. It is now comprised of over 100 hospitals, both freestanding children’s hospitals and pediatric facilities housed inside of larger, adult systems. The collaboration leverages voluntary participation and high-reliability organization principles to successfully decrease serious safety events in hospitals [29]. The network continues to grow, both in participants and in scope.

Learning health systems (LHS), originally defined by the Charles Friedman and the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Science) in 2015, comprise a specific subset of clinical networks [30•, 31, 32]. LHS are centered and built around four major tenets: Science and Informatics, patient-clinician partnerships, incentives, and culture. The Informatics component is further subdivided into two categories, access to real-time data and knowledge, and digitally capturing the care experience so knowledge can be generating from the processes and data recorded. LHS are also built upon the premise of continuous cycles of improvement and feedback.

Overuse of therapies or treatments

The US healthcare system has traditionally focused on using medical treatments or interventions to achieve better clinical outcomes. In the last decade, however, an increasing amount of attention and effort has been spent doing exactly the opposite—scrutinizing treatments and determining the value of their implementation. This determination is often carried out in comparative effectiveness or non-inferiority studies, frequently with a goal of gathering evidence to support the cessation of costly or unproven therapies. The Choosing Wisely campaign, originally sponsored by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation and now espoused by the American Academy of Pediatrics, is a prime example of these efforts [33,34,35,36]. Pediatric Choosing Wisely targets include the non-judicious use of antibiotics for apparent viral respiratory illnesses, the minimization of inappropriate imaging when data shows very little or no benefit for a specific indication, and discouraging routine use of infant apnea monitors to prevent SIDS, among others.

Health information technology has been pivotal in promoting antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) and ASPs in pediatric facilities, and these programs have shown impressive clinical outcomes [37,38,39,40,41,42]. A primary function of these programs is to ensure high quality and appropriate use of antibiotics in order to promote good of resources, cost-containment, and most importantly, to combat antibiotic resistance by limiting the exposure of bacteria and other organisms to antibiotics. The informatics software and tools that ASPs are utilize, however, are subject to the same human factors considerations and workflow integration as traditional EHR tools [42]. Poor implementation and suboptimal workflow integration will limit the usefulness and power of ASPs.

ASPs have become so commonplace in large institutions that quality metric frameworks have been introduced and debated in the literature by many investigators, and systematic reviews are now available [38, 43,44,45,46].

There are many other important concepts in quality improvement that are heavily influenced and dependent on health information technology, but population health management, research and QI networks, and the focus on eliminating low-value diagnostic and treatment interventions are particularly hot topics in healthcare today. These concepts and strategies, when powered by HIT and informatics best practices, have tremendous potential to change healthcare practice for the better and realize the promise of improved clinical outcomes.

ImproveCareNow—an example that brings these concepts together

One of the better known large-scale examples in pediatrics where all of the above concepts have been applied successfully is the ImproveCareNow network-based learning health system [47]. ImproveCareNow has a robust IT infrastructure facilitating its successes [48]. The overall functional architecture of ImproveCareNow includes the infrastructure to support cohort identification, data quality, quality improvement, population management, and pre-visit planning (Figure 1 in the above reference).

ImproveCareNow’s main charge is to improve chronic disease management; in this case, it focuses on reducing flares or exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease in the pediatric population. ImproveCareNow has matured over time to adhere to principles of only handling data once, automating reporting and analysis, and aims to move towards a more “vendor-agnostic” approach. ImproveCareNow is a true population management learning health system that focuses on making sure patients with chronic disease receive the right amount of therapy to achieve optimal outcomes. To date, the network has had many successes in closing care gaps (such as improving appointment visit rates), improving communication between patients/families and providers, and most importantly, decreasing exacerbation rates [49, 50]. Technology, including a robust patient registry, has been pivotal to their efforts.

Information technology-specific challenges in quality improvement

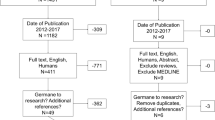

We would be remiss not to recognize and enumerate a few key technology-specific challenges that exist in modern-day quality improvement efforts. Three main issues that we will discuss briefly are the challenges associated with data management and the quality of the data itself, technical interoperability concerns, and problems with quality reporting.

Data management and quality of the data

It is very common for data requestors to underestimate how difficult it can be to work with data, especially when it is being reused or purposed for reasons other than why it was originally generated, i.e., secondary use of data. This is a very common practice and is also often used for research and public health surveillance as well [51]. Primary use of data, that is data collected used for its original purpose, confers the advantage of being designed to meet the desired goal, but can be expensive to collect and manage. Secondary use of data, on the other hand, is relatively inexpensive to collect from an effort standpoint (because it already exists), but usually has quality issues since it is essentially being recycled. There are often many unique challenges to understanding the limitations of secondary data, especially when the secondary use is for quality improvement [52]. A potential pitfall is that it is often necessary to understand the workflows and circumstances under which the data was generated, collected, and transformed as it was processed. It is very common for idiosyncratic workflows to generate anomalous patterns in the data that may lead to misinterpretation. Other issues with data integrity such as completeness can be difficult to detect when the dataset or corpus is very large.

As a practical example, consider the maintenance of a large patient registry. If the data generated by the registry is used by someone unfamiliar with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the cohort that the data represents may not be the actual cohort of interest to the investigator, which would lead to potentially false conclusions upon analysis. In addition, many registries require some manual curation to be accurate, which creates an opportunity for issues depending due to inter- and intra-curator reliability in their curation activities. In general, data management, validation, interpretation, and quality checks are typically more time-consuming and difficult than one would expect at the outset.

Technical interoperability

Much of the original studies touting the national benefits of EHRs and associated systems were based upon the underlying assumption that individual systems would be technically interoperable, meaning that one EHR could more easily “talk” and transmit data seamlessly with a different EHR system at another institution or facility. Despite the proliferation and maturation of technical standards, protocols, guidelines, and conventions, interoperability remains a frequently discussed and lamented challenge. Without true interoperability, data exchange is non-existent, inefficient, or oftentimes very limited as is the case with view-only exchange of data (not readily usable for automated clinical decision support, for instance). Research and improvement networks will often overcome this challenge by building common data exchange models and protocols, but this is extremely time-consuming and no solution is universal for all use cases, so the gains are limited. EHR vendors have come under increasing pressure from federal and academic sources to improve the interoperability of their products [53].

Quality reporting

Healthcare providers and their organizations are increasingly required or incentivized to report on the quality of the services and care they provide to their patients. Many federal agencies, payors, and external auditors (for certification or regulation purposes) often have very different criteria for what they define as quality. The onus, therefore, falls on the providers and their facilities to meet these reporting requirements from multiple sources. One incorrect assumption that many will make is that the adoption and use of EHRs and other technology has made reporting easier and more automated. A counter-observation is that since healthcare is now largely digital, the expectations and requirements to prove quality and value have created an even bigger reporting burden. One particular bit of added complexity for pediatrics is that much of the reimbursement for services comes from Medicaid, which is largely overseen at the state level (unlike Medicare, where funding decisions are typically made at the Federal level). As such, there is often variance in what states are required to report on, and their ability to do so [54•]. Measures may also change over time, and it is not uncommon for large healthcare organizations to maintain reports covering multiple versions of the relatively same measure for both internal and external needs. Fortunately, however, there have been recent pressures to align quality measures across multiple sources, which could alleviate some of the current challenges with quality reporting.

AHRQ: federal agency supporters of using health information technology for quality improvement

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is a primary funder and supporter of using HIT for quality improvement. The study and support for this work has been previously focused into specific initiatives, including HIT-enabled quality measurement (2012–2013), Ambulatory Safety and Quality Program (2007–2013), and the Transforming Healthcare Quality Through HIT (2004–2010). The AHRQ website can be found at https://healthit.ahrq.gov. Their website is a valuable source for many things, including introductory materials, funding opportunity details, and toolkits including implementation guides and evaluation methods. They even have a pediatric-specific section on the website, which contains reports on recommended specifications for pediatric functionality in EHRs, sample pediatric care documentation templates, and information regarding rules and electronic reminders supporting pediatric-specific clinical decision support tools.

In addition, the broader HealthIT.gov website contains more broad information about the benefits of EHRs (https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/health-care-quality-convenience). It also houses the electronic Clinical Quality Improvement (eCQI) Resource Center, which contains a wealth of information about electronic QI measures and reporting, education opportunities, standards, tools, and more.

Conclusion

Health information technology is a foundational tool for quality improvement in modern healthcare. When combined with other QI tools and skills, it can be a great enabler for change in research, education, and healthcare delivery, leading to vast improvements in value and quality. HIT for QI is not without its own challenges, and these obstacles must be recognized, addressed, and mitigated to potentiate true change in our processes and outcomes. This article was meant to introduce the reader to each of these aspects.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:• Of importance •• Of major importance

Services HaH. HITECH Act Enforcement Interim Final Rule. 2017. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/special-topics/HITECH-act-enforcement-interim-final-rule/index.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

• Adler-Milstein J, Jha AK. HITECH act drove large gains in hospital electronic health record adoption. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(8):1416–22. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1651. This article highights and directly attributes EHR adoption gains to the HITECH Act

Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) DpoHaHS. Health information technology: initial set of standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for electronic health record technology. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75(144):44589–654.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) HHS. Medicare and Medicaid programs; electronic health record incentive program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2010;75(144):44313–588.

Gabriel MH, Jones EB, Samy L, King J. Progress and challenges: implementation and use of health information technology among critical-access hospitals. Health Affair. 2014;33(7):1262–70. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0279.

Kruse CS, Kristof C, Jones B, Mitchell E, Martinez A. Barriers to electronic health record adoption: a systematic literature review. J Med Syst. 2016;40(12):252. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-016-0628-9.

Kirkendall ES, Goldenhar LM, Simon JL, Wheeler DS, Andrew Spooner S. Transitioning from a computerized provider order entry and paper documentation system to an electronic health record: expectations and experiences of hospital staff. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(11):1037–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2013.08.005.

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759–69. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759.

Whittington JW, Nolan K, Lewis N, Torres T. Pursuing the triple aim: the first 7 years. Milbank Q. 2015;93(2):263–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12122.

Hyman D, Neiman J, Rannie M, Allen R, Swietlik M, Balzer A. Innovative use of the electronic health record to support harm reduction efforts. Pediatrics. 2017;139(5):ARTN e20153410. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3410.

Starmer AJ, Landrigan CP, Group IPS. Changes in medical errors with a handoff program. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(5):490–1. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1414788.

Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, Hackbarth AD, Goldmann DA, Sharek PJ. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(22):2124–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1004404.

King WJ, Paice N, Rangrej J, Forestell GJ, Swartz R. The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–9.

Kaushal R, Barker KN, Bates DW. How can information technology improve patient safety and reduce medication errors in children’s health care? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. vol 9. United States 2001. p. 1002–7.

Bates DW, Teich JM, Lee J, Seger D, Kuperman GJ, Ma'Luf N, et al. The impact of computerized physician order entry on medication error prevention. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 1999;6(4):313–21.

Makary MA, Daniel M. Medical error-the third leading cause of death in the US. BMJ. 2016;353:i2139. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i2139.

Samaan ZM, Brown CM, Morehous J, Perkins AA, Kahn RS, Mansour ME. Implementation of a preventive services bundle in academic pediatric primary care centers. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20143136. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-3136.

Lail J, Schoettker PJ, White DL, Mehta B, Kotagal UR. Applying the chronic care model to improve care and outcomes at a pediatric medical center. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(3):101–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2016.12.002.

• Nelson EC, Dixon-Woods M, Batalden PB, Homa K, Van Citters AD, Morgan TS, et al. Patient focused registries can improve health, care, and science. BMJ. 2016;354:i3319. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i3319. Publication highlights the potential of registries, their functions, and how they feed quality improvement efforts

Fleurence RL, Curtis LH, Califf RM, Platt R, Selby JV, Brown JS. Launching PCORnet, a national patient-centered clinical research network. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2014;21(4):578–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002747.

Fleurence RL, Beal AC, Sheridan SE, Johnson LB, Selby JV. Patient-powered research networks aim to improve patient care and health research. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1212–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0113.

Curtis LH, Brown J, Platt R. Four health data networks illustrate the potential for a shared national multipurpose big-data network. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(7):1178–86. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0121.

Collins FS, Hudson KL, Briggs JP, Lauer MS. PCORnet: turning a dream into reality. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2014;21(4):576–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002864.

Corley DA, Feigelson HS, Lieu TA, McGlynn EA. Building data infrastructure to evaluate and improve quality: PCORnet. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):204–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.003194.

Margolis PA, Peterson LE, Seid M. Collaborative chronic care networks (C3Ns) to transform chronic illness care. Pediatrics. 2013;131(Suppl 4):S219–23. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3786J.

•• Billett AL, Colletti RB, Mandel KE, Miller M, Muething SE, Sharek PJ, et al. Exemplar pediatric collaborative improvement networks: achieving results. Pediatrics. 2013;131(Suppl 4):S196–203. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3786F.Report on exemplar pediatric-specific QI networks and their results

Lyren A, Brilli R, Bird M, Lashutka N, Muething S. Ohio Children’s Hospitals’ solutions for patient safety: a framework for pediatric patient safety improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2016;38(4):213–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhq.12058.

Schaffzin JK, Harte L, Marquette S, Zieker K, Wooton S, Walsh K, et al. Surgical site infection reduction by the solutions for patient safety hospital engagement network. Pediatrics. 2015;136(5):e1353–60. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0580.

Lyren A, Brilli RJ, Zieker K, Marino M, Muething S, Sharek PJ. Children’s Hospitals’ solutions for patient safety collaborative impact on hospital-acquired harm. Pediatrics. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3494.

• Friedman C, Rigby M. Conceptualising and creating a global learning health system. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(4):e63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2012.05.010. Paper describing learning health systems from leaders on the subject

Rubin JC, Friedman CP. Weaving together a healthcare improvement tapestry. Learning health system brings together health data stakeholders to share knowledge and improve health. J AHIMA. 2014;85(5):38–43.

Friedman CP, Wong AK, Blumenthal D. Achieving a nationwide learning health system. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(57):57cm29. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.3001456.

Rumball-Smith J, Shekelle PG, Bates DW. Using the electronic health record to understand and minimize overuse. JAMA. 2017;317(3):257–8. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.18609.

Feldman LS. Choosing Wisely((R)): things we do for no reason. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(10):696. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2425.

Ho T, Dukhovny D, Zupancic JA, Goldmann DA, Horbar JD, Pursley DM. Choosing wisely in newborn medicine: five opportunities to increase value. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):e482–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0737.

Quinonez RA, Garber MD, Schroeder AR, Alverson BK, Nickel W, Goldstein J, et al. Choosing wisely in pediatric hospital medicine: five opportunities for improved healthcare value. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):479–85. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.2064.

Lee BR, Goldman JL, Yu D, Myers AL, Stach LM, Hedican E, et al. Clinical impact of an antibiotic stewardship program at a Children’s hospital. Infect Dis Ther. 2017;6(1):103–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-016-0139-5.

Kallen MC, Prins JMA. Systematic review of quality indicators for appropriate antibiotic use in hospitalized adult patients. Infect Dis Rep. 2017;9(1):6821. https://doi.org/10.4081/idr.2017.6821.

McCulloh RJ, Queen MA, Lee B, Yu D, Stach L, Goldman J, et al. Clinical impact of an antimicrobial stewardship program on pediatric hospitalist practice, a 5-year retrospective analysis. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(10):520–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2014-0250.

Hersh AL, De Lurgio SA, Thurm C, Lee BR, Weissman SJ, Courter JD, et al. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in freestanding children’s hospitals. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):33–9. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2579.

King A, Cresswell KM, Coleman JJ, Pontefract SK, Slee A, Williams R, et al. Investigating the ways in which health information technology can promote antimicrobial stewardship: a conceptual overview. J R Soc Med. 2017;110(8):320–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076817722049.

Chung P, Scandlyn J, Dayan PS, Mistry RD. Working at the intersection of context, culture, and technology: provider perspectives on antimicrobial stewardship in the emergency department using electronic health record clinical decision support. Am J Infect Control. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2017.06.005.

Akpan MR, Ahmad R, Shebl NA, Ashiru-Oredope DA. Review of quality measures for assessing the impact of antimicrobial stewardship programs in hospitals. Antibiotics (Basel). 2016;5(1) https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics5010005.

Morris AM. Antimicrobial stewardship programs: appropriate measures and metrics to study their impact. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2014;6(2):101–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40506-014-0015-3.

Morris AM, Brener S, Dresser L, Daneman N, Dellit TH, Avdic E, et al. Use of a structured panel process to define quality metrics for antimicrobial stewardship programs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(5):500–6. https://doi.org/10.1086/665324.

van den Bosch CM, Hulscher ME, Natsch S, Gyssens IC, Prins JM, Geerlings SE, et al. Development of quality indicators for antimicrobial treatment in adults with sepsis. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:345. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-345.

Crandall W, Kappelman MD, Colletti RB, Leibowitz I, Grunow JE, Ali S, et al. ImproveCareNow: the development of a pediatric inflammatory bowel disease improvement network. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(1):450–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.21394.

Marsolo K, Margolis PA, Forrest CB, Colletti RB, Hutton JJA. Digital architecture for a network-based learning health system: integrating chronic care management, quality improvement, and research. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2015;3(1):1168. 10.13063/2327-9214.1168.

Dykes D, Williams E, Margolis P, Ruschman J, Bick J, Saeed S, et al. Improving pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) follow-up. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u208961.w3675.

Savarino JR, Kaplan JL, Winter HS, Moran CJ, Israel EJ. Improving clinical remission rates in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease with previsit planning. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u211063.w4361.

Hersh WR. Adding value to the electronic health record through secondary use of data for quality assurance, research, and surveillance. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(6 Part 1):277–8.

Ancker JS, Shih S, Singh MP, Snyder A, Edwards A, Kaushal R, et al. Root causes underlying challenges to secondary use of data. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:57–62.

Koppel R, Lehmann CU. Implications of an emerging EHR monoculture for hospitals and healthcare systems. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA. 2015;22(2):465–71. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-003023.

• Shah AY, LL K, Dougherty D, Cha S, Conway PH. State challenges to child health quality measure reporting and recommendations for improvement. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(3):217–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2016.03.001.Important publication from national leaders on quality improvement that demonstrate quality reporting, while a high priority to most state-level stakeholders, is challenging and time- and resource-consuming

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Eric Kirkendall declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Human/Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Quality Improvement

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kirkendall, E.S. Using Information Technology to Improve the Quality of Pediatric Healthcare. Curr Treat Options Peds 3, 386–394 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-017-0100-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40746-017-0100-1