Abstract

The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) is frequently employed over other measures of so-called implicit attitudes because it produces 4 independent and “nonrelative” bias scores, thereby providing greater clarity around what drives an effect. Indeed, studies have sometimes emphasized the procedural separation of the four trial types by choosing to report only the results of a single, theoretically meaningful trial type. However, no research to date has examined the degree to which performance on a given trial type is impacted upon by other stimulus categories employed within the task. The current study examined the extent to which response biases toward “women” are influenced by two different contrast categories: “men” versus “inanimate objects.” Results indicated that greater dehumanization of women was observed in the context of the latter relative to the former category. The findings highlight that the IRAP may be described as a nonrelative, but not acontextual, measure of brief and immediate relational responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) was created as a way to assess natural verbal relations “on the fly” (Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, Stewart, & Boles, 2010). More specifically, the IRAP was designed to capture arbitrarily applicable relational responding, which is posited by Relational Frame Theory (RFT) to account for complex human behavior such as language and higher cognition (see Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, & Roche, 2001; Hughes & Barnes-Holmes, 2016, for detailed treatments). The IRAP has now been employed in a wide range of contexts, including the assessment of such relational responding in domains of both clinical (see Vahey, Nicholson, & Barnes-Holmes, 2015, for a meta-analysis) and social relevance (e.g., Drake et al., 2015; Rönspies et al., 2015) as well as within basic science contexts (e.g., Bortoloti & de Rose, 2012; Hughes, 2012; Hughes & Barnes-Holmes, 2011).

Due to some procedural similarities with other measures such as the Implicit Association Test (IAT; Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwartz, 1998), the IRAP is frequently referred to or employed as a measure of so-called implicit attitudes (e.g., Hussey & Barnes-Holmes, 2012), a term that was borrowed from cognitive psychology and refers to “automatic” behaviors that are emitted outside of awareness or intentionality, under low volitional control and/or with high cognitive efficiency (see De Houwer & Moors, 2010). However, more recent work has emphasized that such references to the IRAP as a measure of implicit attitudes were heuristic in nature and has attempted to clarify the relationship between the cognitive and functional-analytic approaches to such behavioral phenomena (Hughes, Barnes-Holmes, & De Houwer, 2011; Hughes, Barnes-Holmes, & Vahey, 2012; see Barnes-Holmes & Hussey, 2016; De Houwer, 2011, for broader treatments of the relationship between functional-analytic and cognitive psychology). In particular, we have recently called for a refocusing on the IRAP’s original purpose: to aid a fine-grained functional-analysis of arbitrarily applicable relational responding, as it is emitted (Barnes-Holmes, Hayden, Barnes-Holmes, & Stewart, 2008; Hussey, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2015). The current study represents one such effort to more clearly link this procedure (the IRAP) to the theory from which it emerged (RFT).

Previous research using the IRAP often emphasized the task’s ability to produce four separate bias scores (e.g., Dawson, Barnes-Holmes, Gresswell, Hart, & Gore, 2009; Drake et al., 2015; Nicholson et al., 2013; Rönspies et al., 2015) in contrast with the single overall bias score produced by other “relative” measures (e.g., the IAT). Specifically, whereas the IAT presents all four stimulus categories on each trial and assesses the relative bias for one pattern of category pairings over the other (e.g., categorizing “self with life and others with death” vs. “self with death and others with life”; Nock et al., 2010), the IRAP presents individual stimulus category pairings separately across trials and provides separate bias scores for each (e.g., responding to “self–life,” “self–death,” “others–life,” and “others–death” as being true vs. false across blocks; Hussey, Barnes-Holmes, & Booth, 2016). Given that the two label categories and two target categories are never presented within the same trial, the trial types can therefore be described as being procedurally independent (e.g., a “men–objects” trial on the IRAP contains no stimuli from the categories “women” or “humans”).

However, despite this procedural property of the task, no study has ever examined whether behavior emitted on one trial type is influenced by the context set by the other trial types. Given that the IRAP was created as a way to assess natural or preexperimentally established verbal relations, it would seem important to consider how contextual control over such verbal behavior is exerted within the task itself. Indeed, previous research has noted that “the precision of any particular IRAP is fundamentally intertwined with the degree of experimental control it is capable of applying to a given analytic question” (Vahey, Boles, & Barnes-Holmes, 2010, p. 469). The current study therefore sought to explore one such source of contextual control within the task, as will now be expanded upon.

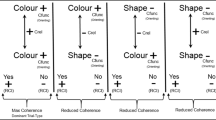

It is worth highlighting that the IRAP attempts to assess the relative strength of relational responding in the presence of pairs of stimulus classes that form the trial types. For example, the left panel of Fig. 1 illustrates the trial types that are formed by the combination of the four categories within a notional gender IRAP: specifically, “women–objects,” “women–human,” “men–objects,” and “men–human.” However, it should be noted that these the trial types represent only a subset of all possible combinations of the four categories. Specifically, trial types are formed by the pairing of one label stimulus (e.g., women or men) and one target stimulus (e.g., objects or human) and not by pairing both label stimulus categories or both target stimulus categories. That is, no “men–women” trial type or “objects–human” trial types would be presented within a typical IRAP. Nonetheless, we argue that it is likely that individuals’ preexperimental history of relating the two label categories and/or two target categories will influence their behavior within the task, even though these specific category pairings are not presented, because the label–label and target–target relations contribute to the broader context that is set within the measure. In order the examine this, the current study manipulated what can be referred to as the “contrast category” (i.e., “men” vs. “inanimate objects”) in order to observe changes on the “category of interest” (i.e., “women”; see Fig. 1; see Karpinski, 2004, for a similar approach).

The stimulus categories employed in the Gender and Agency IRAPs. Note. Solid arrows indicate trial types that were common to both IRAPs (i.e., “women–objects” and “women–human”), whereas dashed arrows indicate trial types that differed between the two IRAPs (e.g., “men–human” vs. “inanimate objects–human”)

We elected to employ dehumanization of women as our target domain (i.e., the denial of women’s subjectivity, individuality, and/or ability to make choices; see Haslam, 2006; Nussbaum, 1995). This domain appeared to be broadly suitable for this research question given society’s mercurial attitudes toward women. Specifically, previous research has shown that there is a general tendency for women to be evaluated more positively than men (e.g., as the more helpful, kind, and empathic gender; see Eagly, Mladinic, & Otto, 1991). However, research elsewhere has demonstrated that women are, simultaneously, all too often stereotyped as being ill-suited to leadership in occupational settings (see Eagly & Karau, 2002, for a review). Importantly, this difference in evaluations of women as either positive (e.g., “empathic”) or negative (i.e., “weak”) has been shown to be highly context-dependent. That is, women are problematically rendered by society as good caretakers and bad leaders (e.g., Glick et al., 2004; see Rudman & Glick, 2001, for an in-depth treatments of these issues). We therefore attempted to utilize these differential, context-dependent evaluations of women in the present study.

Stimulus categories were taken from a published study on the implicit dehumanization of women (Rudman & Mescher, 2012) using the IAT. Two IRAPs were created that differed only in their contrast category. The Gender IRAP employed stimuli identical to those used by Rudman and Mescher (2012; Experiment 2—i.e., women, men, objects, and human). A second IRAP was created as a variant of the first: The Agency IRAP replaced the category “men” with “inanimate objects” (see Table 1), based on the assumption that such everyday items would be more strongly coordinated with “objects” than the “women” stimuli. In so doing, it sought to change the dimension of comparison from the gender of women (i.e., male vs. female) to the agency of women (i.e., capable of independent action, possessing mind and autonomy).

We hypothesized that “women” would be differentially objectified and/or humanized by adult male participants across the two IRAPs depending on the context in which these stimulus classes were presented (i.e., “men” vs. “inanimate objects”), on the basis that the contrast categories were intended to set a different context for responding to “women” within the task (i.e., gender vs. agency), and despite the fact that the stimuli presented on those trial types were identical in both cases. Given the novelty of this manipulation, and the sometimes-counterintuitive nature of implicit biases within socially sensitive domains, no specific hypotheses were made about the direction of such effects. However, it is useful to note that the specific form that such a difference might take is less important here, given that we are primarily interested in the more general argument that the contrast category influences responding to the category of interest. Should such differences emerge, results would therefore demonstrate that the contents of one category within the IRAP provide a potentially important source of contextual control over responding to the other categories.

Method

Sample

The current study employed only participants who identified as both male and heterosexual, in order to limit the number of possible sources of contextual control over participants’ performances. It is therefore useful to reemphasize here that the current study employed the domain of dehumanization of women but did not seek to explore this domain directly. Forty-three male undergraduate students at the National University of Ireland Maynooth (M age = 20.2, SD = 2.0) were recruited. Participants reported that they had completed between zero and 10 previous IRAPs (M = 1.4, SD = 2.2). Inclusion criteria were fluent English (determined via self-report), normal or corrected-to-normal vision, age 18–65 years, full use of both hands, and self-identification as male and heterosexual. No incentives were offered for participation. Participants were randomly allocated to two groups in equal numbers, each of which completed either a Gender IRAP or an Agency IRAP (see below). Two self-report measures were also employed in order to establish that the two groups demonstrated equivalent levels of self-reported sexist attitudes.

Screening Measures

Attitudes Toward Women Scale

The Attitudes Toward Women Scale (ATWS) is a widely used measure of sexist beliefs against women, which was used to compare the two groups on their levels of self-reported sexist attitudes toward women. This 25-item scale asks participants to respond to statements which are either overtly sexist or egalitarian, such as “There should be a strict merit system in job appointment and promotion without regard to sex” and “It is insulting to women to have the ‘obey’ clause remain in the marriage service” (Spence, Helmreich, & Stapp, 1973). It uses a 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) response format. Internal consistency was good in the current sample (Cronbach’ss α = .72).

Likelihood to Sexually Harass Scale

The Likelihood to Sexually Harass Scale (LSH; Pryor, 1987) was used to compare the two groups on their levels of self-reported sexual objectification of women. This scale asks participants to read 10 paragraph-length depictions of specific scenarios and then to respond to three items for each scenario. Each item asks the participants to imagine that they are working in a specific position of power (e.g., as an editor for a large publisher) and that they have an interaction with a young, attractive, and/or junior woman. Three questions are then presented that ask whether the participant would be likely to show preferential bias for such a woman under three different conditions. Subscale A does not specify a contingency for this preferential bias (e.g., “Would you agree to read Betsy’s novel?”), Subscale B specifies that it is in return for sexual favors (e.g., “Would you agree to reading Betsy’s novel in exchange for sexual favors?”), and Subscale C specifies that it is in return for going on a date (e.g., “Would you ask Betsy to have dinner with you the next night to discuss your reading her novel?”). Each item employs a 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (very likely) response scale. Internal consistency was excellent in the current sample (α = .91).

Gender and Agency IRAPs

The IRAP’s structure has been detailed at length elsewhere (e.g., Barnes-Holmes, Barnes-Holmes, et al., 2010), thus, only a brief outline of the specific task parameters employed will be provided here. The 2012 version of the IRAP program was used. As previously stated, stimuli for the Gender IRAP were drawn from Rudman and Mescher (2012), who used the categories “women,” “men,” “objects,” and “humans.” In order to create the second IRAP through the use of a contrast category manipulation, the category “men” was replaced with “inanimate objects” in the Agency IRAP (see Table 1). As such, all stimuli were identical in both IRAPs other than those in the contrast categories.

Each of the label and target stimuli presented in Table 1 was entered twice so that each block of trials on the IRAP consisted of 32 trials and contained an equal number of the four trial types (i.e., Gender IRAP: women–objects, women–human, men–objects, and men–human; Agency IRAP: women–objects, women–human, inanimate objects–objects, and inanimate objects–human). Participants were presented with pairs of blocks, across which the required correct and incorrect responses alternated. For example, in an “A” block, when presented with the stimuli “women” and “human,” participants were required to select one response option (“different”), whereas in a “B” block they were required to select the other response option (“similar”). Participants responded using the “d” and “k” keys for the left and right response option, respectively. The location of the response options on screen alternated pseudorandomly between trials. If participants emitted an incorrect response, a red “X” appeared, and a correct response was required to continue to the next trial. If participants took more than 2000 ms to respond on a given trial, a red “!” appeared on screen. After each trial, the screen cleared for 400 ms. Finally, the order of initial presentation of the two blocks (A vs. B) was counterbalanced between participants.

Participants were presented with up to four pairs of practice blocks in which to attempt to meet the mastery criteria (i.e., accuracy ≥80 % and median latency ≤2000 ms on both blocks within a pair) before being presented with exactly three pairs of test blocks. If participants did not meet the mastery criteria after four pairs of blocks, the task ended without presentation of the test blocks. A responding rule was presented to participants before each block. For the Gender IRAP, Rule A was “Women are objects and men are human” and Rule B was “Women are human and men are objects.” For the Agency IRAP, Rule A was “Women are human and inanimate objects are objects” and Rule B was “Women are objects and inanimate objects are human.” After each block, participants were presented with feedback about their accuracy and latency performance on the previous block, as well as the accuracy and latency mastery criteria.

Procedure

All experimental sessions were conducted one-to-one with a trained researcher in an experimental cubicle. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant prior to participation, followed by a verbal assessment by the researcher of all inclusion criteria. First, participants completed a demographics questionnaire, followed by the ATWS and LSH. They were then randomly assigned to the Gender IRAP and Agency IRAP conditions in equal number.

Participants were verbally instructed in how to complete the IRAP in several stages using a prewritten script. No additional written or on-screen instructions were provided. The experimenter’s verbal instructions for both IRAPs contained the following five key points, which were delivered before the participant completed the first practice block. If a participant indicated a lack of clarity around any point, as the researcher worked through the script, and that point was reiterated and clarified to the participant’s satisfaction. (1) For the Gender IRAP, participants were instructed that they would be presented with pairs of words related to “women” and “men” as being “human” or “objects” and would be asked to respond to those pairs as being “similar” or “different.” Instructions for the Agency IRAP referred to “inanimate objects” instead of “men.” (2) They were informed that, unlike a questionnaire that asked for their subjective opinion, this behavioral task simply required that they follow a rule, and this rule would be provided on-screen. (3) Next, participants were instructed that the rule would swap after each block, that there were only two rules, and that they would be reminded of the rule for the following block on-screen. (4) It was emphasized that they were to initially go as slowly as they needed to get as many trials as possible “right” according to the rule, and that they would naturally become faster with practice. Furthermore, it was emphasized to each participant that he must learn how to respond accurately before learning to respond both quickly and fluently. Once he had learned to be accurate, he should then naturally learn to speed up.Footnote 1 (5) Finally, participants were then informed that they would complete pairs of practice blocks until they learned to meet accuracy and speed criteria, which would be presented at the end of the block. Once these were met, they would then complete three pairs of test blocks. Upon completion of the IRAP, participants were fully debriefed and thanked for their time.

IRAP Data Processing

Performances on the IRAP were processed using common practices (see Hussey, Thompson, McEnteggart, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2015, for an article-length treatment). Specifically, raw latencies on the IRAP test blocks were converted into D IRAP scores in order to control for extraneous variables such as age and responding speed. The D IRAP score is a variant of Greenwald and colleagues’ (2003) D 1 score in order to account for the IRAP’s four separate trial types (see Hussey, Thompson, et al., 2015). They will hereafter be referred to as D scores for simplicity. In order to calculate split-half reliability, separate D scores were also calculated for odd and even trials by order of presentation. This too was done separately for each trial type.

Next, D scores were excluded from the analysis based on accuracy (accuracy ≤78 %) and latency (median latency ≥2000 ms) mastery criteria. This was done based on the following criteria: If a participant failed to maintain the criteria on both blocks within a single test-block pair, it was excluded from the calculation of their final D scores. If more than one test-block pair was failed, that participant’s data were excluded from the analysis. The remaining test block pairs were averaged to create four D scores, one for each trial type. Two participants failed only one test block, and therefore the data from that block pair were excluded from the calculation of their final D scores. One further participant failed more than one test-block pair and therefore had his data excluded from the analyses. No participants were excluded on the basis of having failed to meet the mastery criteria in the practice blocks. Forty-two participants therefore remained in the final sample, 21 in each group. Finally, data from two of the trial types (“women–objects” and “women–human”) were inverted (i.e., multiplied by −1). As such, positive D scores may be interpreted as indicating a humanized or deobjectified bias, and negative D scores may be interpreted as indicating an objectified or dehumanized bias.

Results

Demographics and Screening Measures

Independent t tests demonstrated that the Gender IRAP and Agency IRAP groups did not differ in terms of their age (p = .15), IRAP experience (p = .33), or scores on either the ATWS (p = .67) or LSH (p = .75). While the two self-report measures were specifically included only in order to assess the equivalence of the two groups, it is worth noting that performance on the IRAPs’ women–human or women–objects trial types was not correlated with scores on the ATWS (rs = −.02 to .01) or LSH (rs = .10 to .32; differences between IRAP conditions nonsignificant, ps > .29). This lack of correlation with the LSH is consistent with previous research by Rudman and Mescher (2012).

IRAPs

The current study was concerned with whether IRAP effects would differ on trial types that presented exactly the same stimuli but in which the context provided by the contrast categories (i.e., on the other trial types) differed. As such, only the data from the “women” trial types (i.e., “women–objects” and “women–human”) will be presented and analyzed here (data analyses for the other trial types are available from the first author upon request).

Mean D scores on both IRAPs are depicted in Fig. 2. As predicted, the contrast category manipulation appeared to influence performances on one of the “women” trial types (i.e., “women–human”). A 2 × 2 mixed within-between ANOVA was conducted, with IRAP type (gender vs. agency) as the between-participants variable and IRAP trial type (women–objects vs. women–human) as the within-participants variable. No main effects for IRAP type (p = .13) or trial type (p = .11) were found, but the interaction was significant, F(1, 40) = 4.10, p < .05. Follow-up independent t tests were then used to explore differences on the individual trial types between the two IRAPs. Critically, a large and significant difference was found between the “women–human” trial type across the two IRAPs, t(40) = 2.27, p < .03, Hedges’ g s = .69. Participants therefore dehumanized women differentially, depending on whether “women” were contrasted with “men” (i.e., along the dimension of gender: M = −.14, SD = .41) or with “inanimate objects” (i.e., along the dimension of agency: M = −.41, SD = .33). However, no such differences emerged for the “women–objects” trial type: participants objectified women to a similar extent in the context of “men” (M = −.16, SD = .35) and “everyday objects” (M = −.20, SD = .42, p = .4).

Finally, split-half reliability was calculated using Spearman-Brown correlations. This was found to be good on both the Gender IRAP (women–human: ρ = .63; women–objects: ρ = .77) and Agency IRAP (women–human: ρ = .79; women–objects: ρ = .55). Fischer’s r-to-z tests revealed no significant differences between the split-half reliability of either trial type between IRAPs (all ps > .23).

Discussion

The Gender IRAP and Agency IRAP groups did not differ in their age, IRAP experience, their sexist attitudes toward women, or their level of self-reported likelihood to sexually harass women. Therefore, we concluded that any differences between the two IRAPs’ “women” trial types were likely due to the contrast category manipulation (i.e., responding to “women” in the context of “men” vs. “inanimate objects”). Critically, behavior on one of the trial types of interest (i.e., women–human) was found to differ based on the context provided by the contrast category. As such, while the IRAP’s trial types are procedurally nonrelative, behavior within the task is not acontextual. This is the first time that this form of contextual control has been demonstrated within the IRAP. Furthermore, it is worth noting that while the current study manipulated the contents of a label stimulus category between IRAPs, similar contrast category manipulations could in principle be made to the IRAP’s target stimulus categories (i.e., using a target category other than “humans” or “objects” between IRAPs).

Research elsewhere using the IRAP has sometimes targeted a single trial type (e.g., Nicholson et al., 2013). However, the current results indicate that this must be done in the knowledge that behavior within that trial type may be influenced in important ways by the contents of the others. Future research should therefore note that the theoretical reasons for targeting specific trial types in an analysis should be ideally supported by the contextual control brought to bear by the contrast categories. This support could be either (a) theoretical, for example, by selecting optimal contrast categories with considered reference to domain-relevant literature, or (b) empirical, for example, by manipulating the contrast category across IRAPs in order to attempt to target specific functions (e.g., the gender vs. agency of women).

It is worth noting that the current research differs in a key way to previous work on the role of the contrast category within the IAT. Such work pivoted on two central questions: (a) whether the necessity of a contrast category is inherently problematic and, (b) if so, how to overcome it (e.g., De Houwer, 2006; Houben & Wiers, 2006; Huijding, de Jong, Wiers, & Verkooijen, 2005; Karpinski, 2004; Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2005; Ostafin & Palfai, 2006; Palfai & Ostafin, 2003; Pinter & Greenwald, 2005; Robinson, Meier, Zetocha, & McCaul, 2005; Swanson, Rudman, & Greenwald, 2001). Such research has—either tacitly or explicitly—treated the requirement of a contrast category as a procedural “nuisance” that serves to limit the ability to interpret results. In contrast, the procedural separation of the IRAP’s four trial types allows for a different narrative: specifically, that the contrast category could instead be seen as a potentially manipulable source of contextual control within the task. Increased consideration of the choice or manipulation of the IRAP’s contrast category may serve to enhance the precision with which specific relational responses can be targeted, thereby facilitating increasingly fine-grained analyses. Specifically, while the majority of research to date using measures such as the IRAP and IAT has operated under a common assumption about the nature of the relation between stimulus categories (i.e., that they should be “obvious opposites”; see Robinson et al., 2005, p. 208), the current research highlights the fact that relatively less attention has been paid to which specific psychological functions are specified by this relation (e.g., opposite gender vs. opposite in agency), and how this influences behavior within the task.

To take a concrete example, imagine a researcher was interested in brief and immediate responses around self (cf. Remue, De Houwer, Barnes-Holmes, Vanderhasselt, & De Raedt, 2013). The stimulus categories “I am,” “positive,” and “negative” might therefore be used to target self-related evaluative responses. It should be noted, however, that previous research has argued that multiple aspects of self-evaluation are important to psychological well-being, such as evaluations of self relative to others (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), and the relationship between conceptualized self and idealized self (Foody, Barnes-Holmes, & Barnes-Holmes, 2012). Different aspects of self-evaluations such as these could therefore be brought to bear within the IRAP via contrast category manipulations. Two IRAPs could be created, with one targeting the distinction between evaluations of self versus others (e.g., “I am” vs. “Others are”) and a second targeting the conceptualized self versus idealized self (e.g., “I am” vs. “I want to be”). Although the “I am–positive” or “I am–negative” trial types would be identical across both tasks, it is possible that differences would emerge across the across the two tasks (e.g., in mean bias scores and/or predictive validity). Importantly, any differences would be accompanied by greater clarity as to what functional dimension of comparison drives such effects, thereby helping to link such results directly with the domain-specific theories to which they attempt to speak.

It is worth mentioning that, in taking such an approach, one could seriously question the logic of attempting to develop a procedure (e.g., to measure “attitudes,” “associative strengths,” or “relational responding”) that is acontextual or “absolute” in some sense as others have argued (see O’Shea, Watson, & Brown, 2016). That is, we would argue that all measures of so-called implicit attitudes are moderated to some extent by contextual variables. As such, we suggest that it may be more useful to attempt to harness rather than eliminate such sources of contextual control in the service of meeting our analytic goals.

In closing, while we have focused on the question of whether contrast category manipulations can influence behavior on other trial types, it is also worth considering possible reasons for the direction of the specific effect that was found. The current results indicate that women were more strongly dehumanized on the IRAP in the context of “inanimate objects” relative to “men.” Intuitively, one might have expected the opposite pattern (i.e., that women would be humanized when compared with objects). The reasons for this apparently counterintuitive result are unclear at present. One possible post hoc explanation is that the Gender IRAP employed two immediately salient categories (i.e., male vs. female), whereas the Agency IRAP employed a relatively clear category for two trial types (i.e., female) and stimuli that were less clearly a category for two other trial types (i.e., a list of inanimate objects). As such, the orthogonality of the categories within the Gender IRAP may have made it easier to complete than the Agency IRAP, thereby influencing the results. Indeed, a post hoc analysis of the average reaction times on each measure indicated that participants were significantly faster overall to respond on the Gender IRAP (M = 1561 ms, SD = 171) than the Agency IRAP (M = 1824 ms, SD = 282), t(40) = −3.66, p < .001, Hedges’ g s = 1.11. Additionally, it should be noted that two of the “human” stimuli could be said to be stereotyped male traits (i.e., logic and rational). Thus, there may have been a tendency to respond to “women” and “logic” with “different” rather than “similar,” especially in a context where there was a lack of orthogonality elsewhere in the task. Regardless of how such variables impacted on the direction of the effects observed in the current study, it is important to remember that the contrast category did significantly impact on the categories of interest across the two IRAPs.

Notes

Previous articles have often emphasized both speed and accuracy to the participant from the beginning of the task. More recent research, including the present study, has sought to lower attrition rates by separating out the accuracy and speed training aspects of the practice blocks.

References

Barnes-Holmes, D., Barnes-Holmes, Y., Stewart, I., & Boles, S. (2010). A sketch of the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) and the Relational Elaboration and Coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record, 60, 527–542.

Barnes-Holmes, D., Hayden, E., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Stewart, I. (2008). The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a response-time and event-related-potentials methodology for testing natural verbal relations: A preliminary study. The Psychological Record, 58(4), 497–516.

Barnes-Holmes, D., & Hussey, I. (2016). The functional-cognitive meta-theoretical framework: Reflections, possible clarifications and how to move forward. International Journal of Psychology, 51(1), 50–57. doi:10.1002/ijop.12166.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Bortoloti, R., & de Rose, J. C. (2012). Equivalent stimuli are more strongly related after training with delayed matching than after simultaneous matching: A study using the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP). Psychological Record, 62(1), 41–54.

Dawson, D. L., Barnes-Holmes, D., Gresswell, D. M., Hart, A. J., & Gore, N. J. (2009). Assessing the implicit beliefs of sexual offenders using the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure: A first study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 21(1), 57–75. doi:10.1177/1079063208326928.

De Houwer, J. (2006). What are implicit measures and why are we using them? In R. W. Wiers & A. W. Stacy (Eds.), The handbook of implicit cognition and addiction (pp. 11–28). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Houwer, J. (2011). Why the cognitive approach in psychology would profit from a functional approach and vice versa. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(2), 202–209. doi:10.1177/1745691611400238.

De Houwer, J., & Moors, A. (2010). Implicit measures: Similarities and differences. In B. Gawronski & B. K. Payne (Eds.), Handbook of implicit social cognition: Measurement, theory, and applications (pp. 176–193). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Drake, C. E., Kramer, S., Habib, R., Schuler, K., Blankenship, L., & Locke, J. (2015). Honest politics: Evaluating candidate perceptions for the 2012 U.S. election with the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4(2), 129–138. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.04.004.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. doi:10.1037//0033-295X.109.3.573.

Eagly, A. H., Mladinic, A., & Otto, S. (1991). Are women evaluated more favorably than men? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15(2), 203–216. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00792.x.

Foody, M., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2012). The role of self in acceptance and commitment therapy. In L. McHugh & I. Stewart (Eds.), The self and perspective taking: Research and applications (pp. 125–142). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., . . . Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(5), 713–728. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713.

Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464–1480.

Greenwald, A. G., Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197–216. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197.

Haslam, N. (2006). Dehumanization: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(3), 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4.

Hayes, S. C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Roche, B. (2001). Relational frame theory: A post-Skinnerian account of human language and cognition. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press.

Houben, K., & Wiers, R. W. (2006). Assessing implicit alcohol associations with the Implicit Association Test: Fact or artifact? Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 1346–1362. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.009.

Hughes, S. (2012). Why we like what we like: A functional approach to the study of human evaluative responding (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Maynooth, Maynooth, Ireland: National University of Ireland. Retrieved from http://eprints.maynoothuniversity.ie/4329/.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2011). On the formation and persistence of implicit attitudes: New evidence from the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP). The Psychological Record, 61, 391–410.

Hughes, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2016). Relational Frame Theory: The basic account. In R. D. Zettle, S. C. Hayes, D. Barnes-Holmes, & A. Biglan (Eds.), Handbook of contextual behavioral science (pp. 129–178). New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hughes, S., Barnes-Holmes, D., & De Houwer, J. (2011). The dominance of associative theorizing in implicit attitude research: Propositional and behavioral alternatives. The Psychological Record, 61(3), 465–498.

Hughes, S., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Vahey, N. A. (2012). Holding on to our functional roots when exploring new intellectual islands: A voyage through implicit cognition research. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 1(1/2), 17–38. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2012.09.003.

Huijding, J., de Jong, P. J., Wiers, R. W., & Verkooijen, K. (2005). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward smoking in a smoking and a nonsmoking setting. Addictive Behaviors, 30(5), 949–961. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.09.014.

Hussey, I., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2012). The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure as a measure of implicit depression and the role of psychological flexibility. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(4), 573–582. doi:10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.03.002.

Hussey, I., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2015). From Relational Frame Theory to implicit attitudes and back again: Clarifying the link between RFT and IRAP research. Current Opinion in Psychology, 2, 11–15. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.009.

Hussey, I., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Booth, R. (2016). Individuals with current suicidal ideation demonstrate implicit “fearlessness of death.”. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 51, 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.11.003.

Hussey, I., Thompson, M., McEnteggart, C., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Barnes-Holmes, Y. (2015). Interpreting and inverting with less cursing: A guide to interpreting IRAP data. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 4(3), 157–162. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2015.05.001.

Karpinski, A. (2004). Measuring self-esteem using the Implicit Association Test: The role of the other. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(1), 22–34. doi:10.1027/1618-3169.52.1.74.

Nicholson, E., McCourt, A., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). The Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) as a measure of obsessive beliefs in relation to disgust. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2(1/2), 23–30. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2013.02.002.

Nock, M. K., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., Deliberto, T. L., Dour, H. J., & Banaji, M. R. (2010). Measuring the suicidal mind: Implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science, 21(4), 511–517. doi:10.1177/0956797610364762.

Nosek, B. A., Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (2005). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(2), 166–180. doi:10.1177/0146167204271418.

Nussbaum, M. C. (1995). Objectification. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 24(4), 249–291. doi:10.1111/j.1088-4963.1995.tb00032.x.

O’Shea, B., Watson, D. G., & Brown, G. D. A. (2016). Measuring implicit attitudes: A positive framing bias flaw in the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP). Psychological Assessment, 28(2), 158–170. doi:10.1037/pas0000172.

Ostafin, B. D., & Palfai, T. P. (2006). Compelled to consume: The Implicit Association Test and automatic alcohol motivation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 322–327. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.322.

Palfai, T. P., & Ostafin, B. D. (2003). Alcohol-related motivational tendencies in hazardous drinkers: Assessing implicit response tendencies using the modified-IAT. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(10), 1149–1162. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00018-4.

Pinter, B., & Greenwald, A. G. (2005). Clarifying the role of the “other” category in the self-esteem IAT. Experimental Psychology, 52(1), 74–79. doi:10.1027/1618-3169.52.1.74.

Pryor, J. B. (1987). Sexual harassment proclivities in men. Sex Roles, 17(5/6), 269–290. doi:10.1007/BF00288453.

Remue, J., De Houwer, J., Barnes-Holmes, D., Vanderhasselt, M. A., & De Raedt, R. (2013). Self-esteem revisited: Performance on the implicit relational assessment procedure as a measure of self-versus ideal self-related cognitions in dysphoria. Cognition & Emotion, 27(8), 1441–1449. doi:10.1080/02699931.2013.786681.

Robinson, M. D., Meier, B. P., Zetocha, K. J., & McCaul, K. D. (2005). Smoking and the Implicit Association Test: When the contrast category determines the theoretical conclusions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 27(3), 201–212. doi:10.1207/s15324834basp2703_2.

Rönspies, J., Schmidt, A. F., Melnikova, A., Krumova, R., Zolfagari, A., & Banse, R. (2015). Indirect measurement of sexual orientation: Comparison of the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure, viewing time, and choice reaction time tasks. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(5), 1483–1492. doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0473-1.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 743–762. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00239.

Rudman, L. A., & Mescher, K. (2012). Of animals and objects: Men’s implicit dehumanization of women and likelihood of sexual aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 734–746. doi:10.1177/0146167212436401.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1973). A short version of the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (AWS). Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 2(4), 219–220. doi:10.3758/BF03329252.

Swanson, J. E., Rudman, L. A., & Greenwald, A. G. (2001). Using the Implicit Association Test to investigate attitude-behaviour consistency for stigmatised behaviour. Cognition and Emotion, 15(2), 207–230. doi:10.1080/02699930125706.

Vahey, N. A., Boles, S., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2010). Measuring adolescents’ smoking-related social identity preferences with the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) for the first time: A starting point that explains later IRAP evolutions. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10(3), 453–474.

Vahey, N. A., Nicholson, E., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2015). A meta-analysis of criterion effects for the Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure (IRAP) in the clinical domain. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 48, 59–65. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.01.004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The first author was supported by a Government of Ireland Scholarship from the Irish Research Council.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hussey, I., Mhaoileoin, D.N., Barnes-Holmes, D. et al. The IRAP Is Nonrelative but not Acontextual: Changes to the Contrast Category Influence Men’s Dehumanization of Women. Psychol Rec 66, 291–299 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0171-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-016-0171-6