Abstract

Job burnout is characterized by feelings of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion within the context of one’s work. Individuals experiencing burnout are at risk for a range of negative outcomes including increased feelings of stress and emotion strain, negative perceptions of work-life balance, and may ultimately lead to exiting one’s current job or field of employment. Given the well-documented shortages of school psychology practitioners across the USA, it is important to understand the extent of feelings of burnout in the field, causes of these feelings, and potentially effective ways of preventing and/or responding to burnout when it occurs. The current study surveyed practitioners in four Southeastern states regarding current and past feelings of burnout, perceptions of causes of burnout, personal strategies used in dealing with burnout when it occurs, and thoughts regarding the role of training programs in preventing burnout among practitioners. Results indicated that most participants noted feeling some level of burnout at some point during their careers. Commonly identified causes of burnout included feelings of role overload and lack of support from administration. Practitioners also reported a range of strategies as particularly helpful in dealing with feelings of burnout including the importance of training programs emphasizing the importance of self-care and presenting a realistic picture of real-world practice. Implications for future research and practice are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

School psychology is a field that relies heavily on the excellence of its practitioners in order to ensure the delivery of high-quality school-based services to students. Therefore, it is important that school psychologists feel a certain level of satisfaction with and a positive outlook about the duties they perform on an everyday basis. Singh et al. (2016) report that having a passion for one’s work is often highly predictive of feelings of mastery and control over one’s job situation. If school psychologists are passionate about what they do, they are more likely to take pride in their work and to feel a certain responsibility to the students they serve. It is then vital to address any negative feelings among school psychologists that might interfere with this passion and disrupt their services provided, namely job burnout.

The Mayo Clinic (2012) defines job burnout as a state of feeling exhausted physically, emotionally, or mentally within the context of one’s work. These feelings can derive from a variety of factors including holding negative attitudes toward one’s job (Bianchi and Schonfeld 2016), increasing demands/feelings of emotional and physical fatigue (Ilies et al. 2015), and experiencing overall role stress (Richards et al. 2016). Signs of job burnout include lacking energy and motivation to engage in productive work, becoming cynical, and experiencing mental health difficulties (Maslach et al. 1996; Tomoyuki 2014). In fact, Bianchi and Schonfeld (2016) have further identified burnout as a depressive syndrome in its own right characterized by dysfunctional attitudes, ruminative feelings, and a tendency toward making negative attributions. Individuals experiencing feelings of job burnout are then at a greater risk for negative outcomes including increased job stress and perceptions of work-life conflict (Clark et al. 2014). In more extreme cases of job burnout, an individual may ultimately decide to leave his/her place of work or field of employment as a result (Gabel Shemueli et al. 2015).

Given that shortages in school psychology practitioners have been well documented across the USA (Castillo et al. 2014), it is important to understand the extent of feelings of job burnout among school psychologists in potentially contributing to retention difficulties and what those in the field might be able to do to best address this issue. The current study aimed to examine such feelings among a sample of practitioners across the Southeastern USA. This study is an expansion of more recent research indicating the scope of feelings of burnout among school psychologists in this region is often expressed to a higher degree with up to 92% of practitioners reporting experienced some degree of burnout at some point in their careers. (Schilling and Randolph 2017).

Job Burnout as a Construct

Most researchers examining the issue of burnout conceptualize the term as first identified by Maslach and Jackson (1986). These researchers postulated that feelings of burnout are most often characterized by three distinct components: emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and a lower sense of personal accomplishment (PA). That is, individuals experiencing burnout in their current employment are more likely to feel overwhelmed by their current job duties, experience difficult feelings toward clients and/or coworkers, and hold general perceptions of their ineffectiveness in their current job roles. It is then important to discover the degree to which feelings of job burnout conceptualized in this way are currently affecting the school psychology workforce in the USA.

Job Burnout Among School Psychologists

The attrition rate for practicing school psychologists, which can be seen as one potential outcome of job burnout, has been previously estimated to be around 5% annually (Lund and Reschly 1998), which has remained fairly constant over the years. Generally, school psychologists report feeling a fairly high degree of satisfaction with their work. However, previous studies examining rates of practitioners across the USA who report feeling dissatisfied to very dissatisfied with their current jobs indicate that around 10–15% experience such feelings consistently (Anderson et al. 1984; Worrell et al. 2006). Despite these earlier estimates, “it is likely that with the pressure put on schools and the large increase in mental health caseloads for school psychologists, considerable stress is likely” (Kratochwil et al. 2015, pp. 2–3). Given this fact, it is not unreasonable to believe that more recent estimates of the extent of burnout feelings among practitioners may now be higher. Although more recent estimates of burnout in the field are largely lacking, results of a recent study have portrayed that school psychologists may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of emotional exhaustion with one third of practitioners surveyed reporting a high degree of these difficult feelings (Boccio et al. 2016). Furthermore, this same study revealed that school psychologists report higher feelings of depersonalization (noted by less than 5% of practitioners surveyed) and a lower sense of personal accomplishment (noted by 12% of practitioners surveyed) to a lesser degree. As recent research has identified feelings of burnout among school psychologists practicing in the Southeastern USA as a significant concern with 92% of practitioners reporting some level of these feelings throughout their careers (Schilling and Randolph 2017), it is then important to identify what factors are most often noted by school psychologists as contributing to burnout with the ultimate goal of addressing these concerns in a timely manner.

Typical Factors Contributing to Burnout Among School Psychologists

Past research has indicated that a variety of factors may be particularly contributory in leading to feelings of burnout in the field. These factors can be generally categorized as school/job-based characteristics as well as feelings of being supported in one’s current job role. Related to school/job factors, several characteristics of one’s employment have been identified as often leading to feelings of role overload and subsequently to greater feelings of burnout among school psychologists (Proctor and Steadman 2003). These factors include the type of setting worked in (Bolnik and Brock 2005; Gibson et al. 2009) and number of schools served (Proctor and Steadman 2003). In addition, perceptions of one’s worth within the school system including consideration given in school policies (Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006), lack of opportunities for advancement (Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006), and lack of perceived support from administration including supervisors (Gibson et al. 2009; Schilling and Randolph 2017) have also been identified as factors predictive of feelings of burnout in the field. Relatedly, some researchers have identified the pressure to act unethically from others within the school system (i.e., withholding recommendations, supporting inappropriate placements for students) as related to increased feelings of burnout and intention to leave one’s current job (Boccio et al. 2016).

In addition, the results of more recent research have portrayed that it is not only particular school characteristics, but more importantly practitioners’ levels of reported satisfaction with these characteristics that are most predictive of feelings of burnout. For example, stated dissatisfaction with one’s current salary as well as the school psychologist-to-students ratio within the school system in which one works is often more predictive of burnout than merely looking at levels of current salaries or ratios alone (Schilling and Randolph 2017; Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006). That is, one might imagine a school psychologist working in a system with lower salaries and higher practitioner-to-student ratios who is perfectly satisfied with this current situation. As a result, he/she is then less likely to experience feelings of burnout.

Level of perceived social support has also been found to be associated with feelings of burnout among workers in general and particularly among school psychologists (Wang et al. 2016). This support can come in many forms including from family, friends, coworkers, administration, and even from the field in general. Previous studies have shown that support received from one’s district/colleagues (Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006), from direct supervisor (Gibson et al. 2009; Schilling and Randolph 2017), and from state or national school psychology associations (VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006) can be particularly helpful in both preventing and responding to burnout feelings. Interestingly, some practitioners have reported support from friends and family as not as effective in dealing with the issue of burnout as they do not understand the language of the field (Schilling and Randolph 2017).

Finally, research has also focused more recently on identifying protective factors that may exist in preventing the experience of burnout among workers, including school psychologists. These factors include feelings of self-efficacy in being able to competently complete job duties and to navigate the team climate in the work environment (Loeb et al. 2016) as well as resilience in the sense of being able to deal with difficult work situations when they occur (Richards et al. 2016).

Regional Differences in School Psychology Practice and Related Feelings of Burnout

Although a well-informed conclusion regarding regional differences in the extent of job burnout among school psychologists cannot be made at this time, it is reasonable to believe that practitioners in some areas of the USA may be at a greater risk for burnout due to the nature of practice within these respective regions. School psychologists in the Mid- and Southeastern USA often report higher practitioner-to-student ratios, lower satisfaction with salaries, higher numbers of behavioral referrals, and a higher percentage of time spent in assessment activities than their peers in other areas of the country (Hosp and Reschly 2002; Schilling and Randolph 2017). Given that these factors are all well known to be related to negative feelings about one’s job, it is reasonable to believe that they are then more likely to experience higher levels of job burnout in general. It was the goal of the current study to discover the extent to which this is true.

Method

Participants

Participants in the current study included 122 school psychologists working in educational settings in four Southeastern states, representing a response rate of 45%. The majority of participants were female (84.6%) with a mean age of 42.6 (SD = 12.9). Most participants (98.3%) reported working in public school settings representing urban (24.8%), suburban (42.5%), and rural (32.75%) geographic locations. Participants represented a nice distribution across the career spectrum with 26.6% providing services for more than 20 years, 30.2% providing services for between 10 and 19 years, 30.9% providing services for between 5 and 9 years, and 13.3% providing services for less than 5 years. Participant characteristics are fairly consistent with nationwide demographic characteristics of school psychologists collected as part of the most recent membership survey distributed by the National Association of School Psychologists (National Association of School Psychologists 2016) in regard to gender (83% Female) and age (mean = 42.4). Participants in the current study who reported primarily working in public schools (98.3%) represented a higher proportion of practitioners working in this setting in comparison to nationwide data estimated at 86% (National Association of School Psychologists 2016).

Measures

Demographic Form

A demographic form was used to gather information about participants’ age, gender, work setting, geographic location, estimated school psychologist-to-student ratio, salary, and number of annual evaluations completed.

School Psychology Satisfaction and Burnout Questionnaire

The SPSBQ was developed as a tool to gather descriptive information from participants regarding feelings of burnout as well as perceptions of factors contributing to these feelings. Participants were asked to rate their current level of satisfaction with their salary, current school psychologist-to-student ratio, and number of evaluations completed annually on a Likert-type scale ranging from Very Dissatisfied to Very Satisfied.

To examine perceptions of burnout, participants were asked to respond to yes/no questions, forced choice items, Likert-type ratings, and open-ended questions. Participants responded to questions about whether they had experienced feelings of burnout, when they first experienced burnout, how frequently they have experienced feelings of burnout, and how they typically deal with feelings of burnout. They also rated how many particular factors including salary, educational setting, relationship with coworkers, support from state and national organizations, support from administration, insignificant recognition of work, level of access to resources, level of parent involvement, extenuating personal circumstances, role overload, and poor fit with training contributed to current feelings of burnout. Open-ended questions solicited participants’ definition of burnout and beliefs about how school psychology training programs might mitigate the issue of burnout.

The SPSBQ was developed in an effort to address the specific variables identified by previous research as correlated with the general experience of burnout in school psychologists. Initial validity of this measure was established by incorporating these variables into an overall conception of burnout in the field as represented by this measure (Schilling and Randolph 2017).

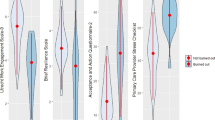

Maslach Burnout Inventory

The Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach and Jackson 1986) for Human Services professionals was administered to participants to examine feelings of Emotional Exhaustion (9 items), Depersonalization (5 items), and Personal Accomplishment (8 items). Emotional exhaustion measures the degree to which individuals report feeling emotionally depleted in relation to work. Depersonalization measures the degree to which health service providers have started to view clients with less personal attachment and connection. Personal Accomplishment measures self-efficacy as it relates to work experiences. Items were rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0, “Never,” to 6, “Every Day.” For each scale, participants could be placed into categories based on their reports of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment. For Emotional Exhaustion, categorization was as follows: Low (scores 0–16), Moderate (scores 17–26), and High (scores 27 and higher). For Depersonalization, categorization was as follows: Low (scores 0–6), Moderate (scores 7–12), and High (scores 13 and higher). For Personal Accomplishment, categorization was as follows: Low (scores 0–31), Moderate (scores 32–38), and High (scores 39 and higher). High scores on the first two scales, Emotional Exhaustion and Depersonalization are considered indicators of burnout. In contrast, low scores on Personal Accomplishment are considered indicators of burnout.

The three-factor structure underlying the construct of job burnout as portrayed on the MBI has been well supported. Additionally, Chronbach’s alpha ratings of .90 for the Emotional Exhaustion scale, .76 for the Depersonalization scale, and .76 for the Personal Accomplishment scale have been reported indicating acceptable to excellent levels of internal consistency of the items representing these scales (Iwanicki and Schwab 1981). Test-retest reliability for the MBI is also acceptable with a reliability coefficient ranging from .60 to .82 over a 4-week span.

Procedures

Participants were solicited through contacting leaders in school psychology state associations and requesting them to send surveys to their membership. Online surveys were administered through Qualtrics and responses were analyzed using SPSS.

Results

Descriptive Data Regarding Feelings of Burnout

The overwhelming majority (90%) of participants reported having experienced feelings of burnout in their role as a school psychologist. The mean age of the participants that reported they had not experienced burnout was not significantly younger [F(1, 108) = .33, p = .57] than those who had experienced burnout. The point in one’s career when participants first experienced burnout varied from their first year into their careers (5.26%) to more than 20 years into their careers (6.32%). Descriptive statistics regarding the frequency of current feelings of burnout experienced by participants are provided in Table 1.

Participants reported that they employ several different strategies for dealing with burnout, including talking to coworkers (73.7%), attempting to change the situation that has caused feelings of burnout (53.7%), doing something to distract themselves (53.7%), talking with family (53.7%), talking with friends (43.2%), and engaging in some other behavior such as yoga, meditation, medication, and physical activity (34.7%).

Contributing Factors to Burnout

Participants were asked to rate the degree to which a variety of factors have contributed to their feelings of burnout. The factors that were identified as contributing the most to burnout were support from administration and role overload. The factors that were identified as contributing the least to burnout included support from state and national organizations and poor fit with training. Table 2 provides percentages for ratings falling in the two extreme categories (“not at all” and “a lot”) for contributing factors.

With regard to satisfaction, participants were asked what has been the outcome of their feelings of burnout. Thirty percent of respondents reported that they are planning to stay in their current job, 21.7% reported that they are thinking about leaving for another job, 18.9% reported that they are thinking about leaving the field, and 29.3% indicated that they are not currently experiencing feelings of burnout.

Qualitative Analysis

Participants provided several ideas for ways that training programs can prepare graduate students to handle burnout. A content analysis of participants’ responses to this question resulted in an identification of the following main recommendations from practitioners: emphasize the importance to students of self-care and stress release, train students to handle a range of mental and behavioral health issues in students, provide a more realistic picture of the roles of psychologists in the schools, focus more on “real” practices rather than best practices, prepare students for other options of practice outside of the schools, provide more training with organization and paperwork, and increase focus on systems-level roles. The categories that were most frequently mentioned by participants were related to self-care and stress management and the mismatch between training programs and their experiences and roles in the “real world.” Many participants identified their training programs as being out of touch with practices in the field. Training programs tended to focus on best practices, rather than what actually happens in schools. Programs also tended to emphasize the multifaceted nature of the position, when the practice of the job tended to be more one-dimensional (i.e., assessment focused) with a good bit of administrative work.

Maslach Burnout Inventory Results

Participants completed the MBI as a measure of feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment related to burnout. The Emotional Exhaustion scale measures feelings of being emotionally depleted as a function of one’s work. For this sample, the mean score on the Emotional Exhaustion scale was 24.8 (SD = 11.2). Using the categorization system provided by the instrument, 45.6% of the sample scored in the High range, 27.7% scored in the Moderate range, and 26.7% scored in the Low range for emotional exhaustion.

The Depersonalization scale measures feelings of impersonal connection and care for clients one is serving. For this sample, the mean score on the Depersonalization scale was 4.9 (SD = 4.4). Using the categorization system provided by the instrument, 5.9% of the sample scored in the High range, 27.7% scored in the Moderate range, and 66.4% scored in the Low range for depersonalization.

The Personal Accomplishment scale measures feelings of self-efficacy related to one’s work. For this sample, the mean score on the Personal Accomplishment scale was 36.2 (SD = 6.7). For this scale, low scores are an indicator of burnout. Using the categorization system provided by the instrument, 25.7% of the sample scored in the Low range, 33.7% scored in the Moderate range, and 40.6% scored in the High range for personal accomplishment.

Discussion

Burnout has been defined as a state of physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion experienced within the context of one’s work (Mayo Clinic 2012). Job burnout appears to occur among workers in all professions for a variety of reasons. In the field of school psychology, the construct of burnout has not been studied as widely as in other school personnel including teachers. Ninety percent of the participants in the current study reported experiencing burnout at some point in their careers as school psychologists, a much higher rate than the 10–15% expressing some level of dissatisfaction with their jobs in previous studies (Anderson et al. 1984; Worrell et al. 2006). These differences may be attributed to a number of factors. For example, it should be noted that while the current study asked participants specifically to indicate whether they have ever experienced feelings of burnout, previous studies have focused more on overall reported feelings of job satisfaction among practitioners. That is, it is reasonable to believe that a school psychologist may feel largely satisfied with his/her job but may also experience some feelings of burnout from time to time in specific areas of their professional lives. The differences may signify a generational shift, with practicing school psychologists now experiencing more burnout than even 11 years ago. That being said, rates of lifetime feelings of burnout expressed by participants in the current study are consistent with results of a more recent study indicating that 92% of school psychologists have experienced feelings of burnout at some point in their careers (Schilling and Randolph 2017). Given that the current study surveyed practitioners in the Southeastern USA, results are also consistent with previous findings that school psychologists practicing in this region of the county often experience work characteristics (e.g., higher assessment caseloads) reflecting the potential for experiencing higher feelings of role overload (Schilling and Randolph 2017).

Feelings of job burnout were measured quantitatively in the current study using the conceptualization of this construct offered by Maslach and Jackson (1986) consisting of three distinct components: feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and a lower sense of personal accomplishment. Participants in the present study noted the highest ratings of burnout related emotional exhaustion. These results are consistent with previous studies linking feelings of overload in response to job responsibilities with burnout (Schilling and Randolph 2017; Wang et al. 2016). The fact that participants in the current study reported relatively lower feelings of depersonalization and higher feelings of personal accomplishment fits with data form other studies indicating that school psychologists report serving the needs of others and feeling that they are making a difference as the most positive aspects of their jobs (Gibson et al. 2009; Singh et al. 2016; Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006; Wang et al. 2016).

In regard to factors typically leading to increased feelings of burnout, previous research has indicated that school/job-related characteristics including salary, school policy, lack of advancement opportunities, a greater need for crisis intervention services, and being assigned to multiple schools are particularly relevant (Bolnik and Brock 2005; Unruh and McKellar 2013; VanVoorhis and Levinson 2006). This study confirmed many of these results indicating that burnout is often determined by a combination of factors, particularly related to role overload and lack of available support from others to deal with subsequent difficult feelings about one’s job.

Protective factors allowing individuals to better deal with feelings of burnout have also been investigated through previous research, and indicate that supportive supervisors and co-workers and increased feelings of self-efficacy, as well as a sense of resilience in being able to deal with difficult situations, are particularly useful (Gibson et al. 2009; Richards et al. 2016; Singh et al. 2016). Results of the current study confirmed many of these with the following strategies noted as particularly useful: talking with co-workers, engaging in solution-focused problem solving methods, and stress reduction techniques.

When examining participants’ responses to a question on the SPSBQ regarding what training programs can do to mitigate the issue of burnout in the field, results from the current study were both consistent and inconsistent with responses from a previous study examining this question (Schilling and Randolph 2017). Participants in both studies stressed the need for training programs to provide a realistic picture of the role of school psychologists (instead of a focus only on best practices). In the current study, the second most common identified theme involved the importance of teaching self-care and stress management versus teaching students how to self-advocate for themselves within the school system as was identified as a major theme in participants’ responses in the previous study (Schilling and Randolph 2017).

Limitations and Future Directions

Limitations of this study include utilizing a relatively small regional sample of practitioners in compared population of school psychologists across the USA. Therefore, it will be important for future research to examine the difficult issue of burnout among practitioners in other areas of the country. A further limitation exists in that the SPSBQ utilized in the current study has not been previously validated as a measure of burnout among school psychology practitioners. The decision to create this survey in the context of a previous study (Schilling and Randolph 2017) was made given the authors’ assertion that a previously validated measure of job burnout such as the MBI is not necessarily sensitive enough to pick up on what factors more specific to the field of school psychology may currently be contributing to feelings of burnout among practitioners. As such, results from both of these instruments were examined together in this study. It is suggested that future research regarding the incidence of burnout in the field continue to utilize such an approach.

Implications for School Psychologists, Schools, and Training Programs

Results of the current study suggest that school psychologists may experience greater levels of burnout than was once reported. Additionally, a substantial number of participants indicated considering leaving the field as a result of these feelings. Participants in this study provided some valuable information for training programs and employers regarding how they may assist in preventing and/or dealing with burnout when it occurs. Training programs may need to provide a more realistic view to students of what the practice of school psychology typically looks like in their region. This includes moving beyond a focus on “best practices” to also regularly discuss issues relevant to the day-to-day functioning of practitioners within the school setting (i.e., working with school administration, navigating professional relationships with coworkers, working with uncooperative individuals, addressing issues faced by school psychologists that may not have reached the level of national attention or issues that may be specific to certain areas of the country, etc.). Additionally, while the role of the school psychologist should include consultation, collaboration, and direct service provision, many states still have psychologists that are predominately assessors for eligibility. Students may feel a disconnection between their training that emphasizes the multidimensional nature of school psychology and the actual unidimensional nature of being a school psychologist in their particular school.

Training programs might accomplish this goal more fully through efforts such as providing more opportunities for practitioners to provide some input regarding the material that is covered in courses. For example, instructors of graduate-level courses in school psychology programs might benefit from sending out syllabi to practitioners in the region or members of their advisory board before the start of a semester in order to get feedback on whether topics covered are best reflective of real-world practices. Programs could also incorporate events in the form of roundtable discussions and other opportunities for students to interact with school psychologists in the region around issues affecting practice in schools. The current researchers’ program does this with an advisory board. The advisory board, composed of school psychologist from the surrounding eight counties, meets with the faculty and current graduate students once per semester to share issues from the field and answer questions from the students. This meeting is both formal (e.g., a roundtable discussion), and informal (e.g., including a dinner).

In the Schilling and Randolph (2017) study, participants suggested trainers need to adequately teach graduate students to advocate for themselves as practitioners (e.g., emphasizing the role they can play in serving students and schools, teaching them grant-writing skills to obtain needed resources, teaching them how to work effectively within the larger community, and how to determine and integrate community resources). One of the practices the researchers have incorporated effectively into their own training program to address this “real world” issue is involving students in a professional service activity for 20 h across each semester. In this setting, they must synthesize information from their training that is rarely a stand-alone “best practice”—but rather requires them to analyze multiple perspectives (e.g., staff, clients, parents, volunteers at the site, resources available) before developing a solution. Students have responded positively to this activity, indicating that it requires them to draw on a number of skills only tangentially taught in the training program (e.g., time management, organizational skills, communicating across a wide range of individuals, and even developing marketing materials for some of the programs they developed). Training programs may also need to address (formally or informally) one of the often-mentioned issues practitioners mentioned: stress reduction. Programs may want to incorporate this as a small part of a course on the profession of school psychology—or direct students to services their colleges or universities provide for stress reduction (e.g., most universities have fitness centers or counseling center groups that offer programs handling stressing).

Finally, there are protective factors that schools and training programs can help to ensure are in place (i.e., providing adequate support in the form of supervision and access to needed materials) to increase the likelihood that school psychologists can prevent or address burnout early before it becomes a significant issue. Again, training programs can begin to emphasize the importance of advocating for such supports as graduates enter the field and schools can assist practitioners in building the level of support needed in ultimately diminishing the likelihood that feelings of burnout will occur. It is believed by the authors that support in the form of adequate post-graduate supervision can be particularly useful to practitioners as they learn to navigate challenging workplace dynamics and perceived impasses to effective service delivery. This can be especially helpful for new practitioners as they enter the field and can take the form of more formal weekly supervision meetings or more informal mentoring relationships with more senior colleagues. Establishing professional mentorships between school psychologists that have been in the field for an extended time and those that are at the early stages of the career may also be beneficial. At the very least, training programs may need to look at current issues practitioners are facing in terms of their curriculum to determine if they are preparing students to practice in the real world—or what practitioners are indicating is the “real world” for them.

References

Anderson, W. T., Hohenshil, T. H., & Brown, D. T. (1984). Job satisfaction among practicing school psychologists: a national study. School Psychology Review, 13, 225–230.

Bianchi, R., & Schonfeld, I. S. (2016). Burnout is associated with a depressive cognitive style. Personality and Individual Differences, 10, 1–5.

Boccio, D. E., Weisz, G., & Lefkowitz, R. (2016). Administrative pressure to practice unethically and burnout within the profession of school psychology. Psychology in the Schools, 53(6), 659–672.

Bolnik, L., & Brock, S. E. (2005). The self-reported effects of crisis intervention work on school psychologists. The California School Psychologist, 10, 117–124. doi:10.1007/BF03340926.

Castillo, J. M., Curtis, M. J., & Tan, S. Y. (2014). Personnel needs in school psychology: a 10-year follow-up study on predicted personnel shortages. Psychology in the Schools, 51(8), 832–849.

Clark, M. A., Michel, J. S., Zhdanova, L., Pui, S. Y., & Baltes, B. B. (2014). All work and no play? A meta-analytic examination of the correlates and outcomes of workaholism. Journal of Management. February 1–38. doi: 10.1177/0149206314522301.

Gabel Shemueli, R., Dolan, S. L., Suárez Ceretti, A., & Nuňez del Prado, P. (2015). Burnout and engagement as mediators in the relationship between work characteristics and turnover intentions across two Ibero-American nations. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. December 1–10. doi: 10.1002/smi.2667.

Gibson, J. A., Grey, I. M., & Hastings, R. P. (2009). Supervisor support as a predictor of burnout and therapeutic self-efficacy in therapists working in ABA schools. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 2012–1030. doi:10.1007/s10803-009-0709-4.

Hosp, J. L., & Reschly, D. J. (2002). Regional differences in school psychology practice. School Psychology Review, 31, 11–29.

Ilies, R., Huth, M., Ryan, A. M., & Dimotakis, N. (2015). Explaining the links between workload, distress, and work-family conflict among school employees: physical, cognitive, and emotional fatigue. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(4), 1136–1149.

Iwanicki, E., & Schwab, R. (1981). A cross validation study of the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association Annual Convention, Los Angeles, CA.

Kratochwil, T. R., Elliott, S. N., & Gettinger, M. (Eds.). (2015). Advances in school psychology (Vol. Vol. 8). New York: Routledge.

Loeb, C. A., Stempel, C., & Isaksson, K. (2016). Social and emotional self-efficacy at work. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57, 152–161.

Lund, A. R., & Reschly, D. J. (1998). School psychology personnel needs: correlates of current patterns and historical trends. School Psychology Review, 27, 816–830.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1986). Maslach burnout inventory (Second ed.). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach burnout inventory manual (3rd ed.). Mountain View: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Mayo Clinic (2012). Job burnout: how to spot it and take action. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-living/adult-health/in-depth/burnout/art-20046642?pg=1.

National Association of School Psychologists (2016). 2015 Member Survey Results. Retrieved from https://www.nasponline.org/research-and-policy/nasp-research-center.

Proctor, B. E., & Steadman, T. (2003). Job satisfaction, burnout, and perceived effectiveness of “in-house” versus traditional school psychologists. Psychology in the Schools, 40, 237–243. doi:10.1002/pits.10082.

Richards, K. A. R., Levesque-Bristol, C., Templin, T. J., & Graber, K. C. (2016). The impact of resilience on role stressors and burnout in elementary and secondary teachers. Social Psychology of Education, 19, 511–536.

Schilling, E. J., & Randolph, M. (2017). School psychologists and job burnout: what can we learn as trainers? Trainers’ Forum: The Journal of the Trainers of School Psychologists, Winter, 69–94.

Singh, P., Burke, R. J., & Boekhorst, J. (2016). Recovery after work experiences, employee well-being and intent to quit. Personnel Review, 45(2), 232–254.

Tomoyuki, K. (2014). Stress model in relation to mental health outcome: job satisfaction is also a useful predictor of the presence of depression in workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(4), e6-e7.

Unruh, S., & McKellar, N. A. (2013). Evolution, not revolution: school psychologists’ changing practices in determining specific learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 50, 353–365.

VanVoorhis, R. W., & Levinson, E. M. (2006). Job satisfaction among school psychologists: a meta-analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 21, 77–90.

Wang, W., Yin, H., & Huang, S. (2016). The missing links between job demand and exhaustion and satisfaction: testing a moderated mediation model. Journal of Management and Organization, 22(1), 80–95.

Worrell, T. G., Skaggs, G. E., & Brown, M. B. (2006). School psychologists’ job satisfaction: a 22 year perspective in the USA. School Psychology International, 27, 131–145. doi:10.1177/0143034306064540.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schilling, E.J., Randolph, M. & Boan-Lenzo, C. Job Burnout in School Psychology: How Big Is the Problem?. Contemp School Psychol 22, 324–331 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0138-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-017-0138-x