Abstract

Purpose of review

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) leads to significant joint damage and systemic complications. Available treatment options for RA has made it possible to achieve a good control over disease activity and improve patient outcomes. In this review, we discuss management guidelines for RA and their practical application by discussing clinical scenarios commonly encountered in rheumatology practice.

Recent findings

European League Against Rheumatism recently updated treatment recommendations for management of RA. The general fundamentals of these recommendations are similar to those of the 2015 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the treatment of RA but with some key distinctions. We discuss three RA cases to illustrate key aspects of treatment guidelines. New data show increased cardiovascular risk in patients with RA that is possibly related to associated systemic inflammation.

Summary

While several questions about RA remain unanswered, the clinical outcomes have improved in recent years. A strategic approach to manage RA is recommended which involves early diagnosis and treatment and escalating treatments to achieve a therapeutic target. In addition to treating RA disease activity, management of comorbid conditions is imperative to prevent long-term systemic damage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory condition that causes joint damage and increases morbidity and mortality via systemic complications [1]. The treatment paradigm of RA has shifted markedly over the past three decades with the development of new therapeutics enabling a tighter control of the disease activity and improvement in outcomes. This strategy, referred to as treat to target, aims to achieve low disease activity or remission and requires frequent measurement of disease activity at clinic visits, and treatment adjustment/titration to achieve the target. Instruments such as clinical disease activity index (CDAI), simple disease activity index (SDAI), and disease activity score (DAS) 28 which utilizes readily available clinical and/or laboratory parameters are commonly being used in clinical practice already (Table 1). These measures assess RA disease activity quantitatively as high, moderate, low, and remission, and RA therapy is then adjusted in order to target low disease activity or remission.

Management of RA in clinical practice

Case 1

Sixty-year-old female with medical history of hypertension presented to her rheumatologist’s office for follow-up of RA, which was diagnosed 1 year ago. She had been taking methotrexate 25 mg oral weekly with 1 mg daily of folic acid. Two months ago, she began noticing increased pain and swelling in her hands, shoulders, and feet. She ran a local baking business and had noticed reduced productivity at work. Examination at the office visit revealed moderate disease activity as measured by CDAI of 16 and Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) score of 3.7.

Case 2

Fifty-year-old female with history of RA presented with complaint of painful discoloration in her toes for 1 week. Patient had history of RA diagnosed 2 years ago. She had begun treatment with adalimumab 4 weeks ago after failure of methotrexate. Patient had no prior history of Raynaud’s phenomenon or another autoimmune disease. Her examination revealed erythematous, violaceous macules in multiple toes bilaterally.

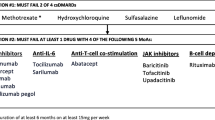

Currently available drugs to treat RA include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), glucocorticoids, conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs; currently approved tsDMARDs in the USA include the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors), and biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs). Biosimilars, products highly similar to already approved biologic drugs, are also being used for the treatment for RA, with a potential for cost-savings. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) have developed treatment algorithms to guide clinicians in management of RA with these drugs [3•, 4••]. While both generally agree on most recommendations, key distinctions are outlined in Table 2. Aletaha et al. highlighted some of the similarities and differences in a recent review [6]. The 2020 ACR RA guideline was pending publication at the time of submission of this article.

Initial therapy

The 2015 ACR treatment guideline distinguishes between early (< 6 months) and established RA (≥ 6 months) based on duration of RA symptoms and offers an algorithm for each scenario, while the EULAR RA treatment guideline does not make this distinction. Nevertheless, the initial treatment recommendations for patients who have not been treated with a DMARD are essentially the same. There is no international consensus on definition of “early RA” based on symptom duration, and is likely to evolve with the discovery of early biomarkers of RA. It is known that joint damage may begin within weeks to months of symptom onset, and radiographic progression may occur in the first 2 years of the disease [7]. Prolonged symptom duration is associated with radiographic progression and a lower chance of sustained remission [8]. Therefore, the treatment of RA should be started as soon as the diagnosis is made with dual goals of improving clinical outcomes and long-term disease prognosis [9].

The preferred initial therapy recommended by both the ACR and the EULAR RA treatment guideline is csDMARD monotherapy. Among csDMARDs, methotrexate (MTX) is the preferred drug of choice as first-line treatment. MTX has several advantages with proven clinical efficacy, safety, and low cost. MTX has shown efficacy in both RA of long duration and early-undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis making it a reasonable initial choice [10]. Although some studies demonstrate superior clinical and radiographic efficacy of using biologic DMARD monotherapy (etanercept) [11] or combination of biologic plus methotrexate (e.g., adalimumab + MTX in PREMIER study, etanercept + MTX in COMET study) or triple therapy [12] as initial treatment for RA compared with MTX alone [13, 14], other studies such as the TEAR study show that long-term outcomes are not impacted if patients start MTX as initial therapy and escalate treatment based on disease activity [15]. Methotrexate in combination with other csDMARDs is also not superior to methotrexate alone when used as initial therapy, with concomitant glucocorticoids [16].

Methotrexate when administered orally or subcutaneously should be escalated within 4–6 weeks to an optimal dose of 20–25 mg weekly. Folic acid should be used, if needed in doses up to 5 mg/day, to reduce the risk of several MTX-associated adverse events [17]. Higher doses of methotrexate may be associated with unwanted adverse effects that may lead to drug discontinuation. In those cases, other csDMARDs, leflunomide or sulfasalazine, should be considered as part of the first-line treatment strategy. Short-term glucocorticoids (< 3 months) as a “bridge therapy” are recommended until csDMARDs has reached its efficacy and should be tapered when feasible. Consideration of intra-articular joint injections is also available as an adjunctive strategy (EULAR). Long-term use of prednisone at dose above 10 mg should be avoided due to the risk of adverse events associated with long-term use. If glucocorticoids cannot be tapered, escalation of DMARD therapy should be strongly considered.

Monitoring should be frequent in active disease, occurring every 1–3 months. If the target disease activity state is not achieved within 3–6 months despite csDMARD monotherapy, treatment should be adjusted. The ACR and EULAR treatment recommendations differ slightly at this stage. The ACR recommends using either combination of csDMARDs or adding or switching to tumor necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) or non-TNFi biologic for both early and established RA. Addition of a tsDMARD (tofacitinib) to methotrexate is a recommended option for established RA (≥ 6 months duration). These options were not in an order of preference due to lack of direct comparative evidence in clinical trials. With most patients with RA present with at least 1–3 months of symptoms and the initial csDMARD monotherapy trial is needed for 2–3 months, almost every patient with early RA meets the established RA definition by the time first escalation from the csDMARD monotherapy is made or within 1–2 months of such a change. After csDMARD monotherapy failure, combinations of csDMARDs (MTX + sulfasalazine (SSZ 3–4 g/day); MTX + leflunomide (20 mg/day); MTX+(hydroxychloroquine (HCQ)400 mg/day); SSZ + HCQ; or triple therapy with MTX + SSZ + HCQ can be used. Triple therapy was non-inferior to etanercept plus methotrexate in patients with RA who had active disease despite methotrexate therapy [18]. A systematic review and network meta-analysis (NMA) of 158 trials with over 37,000 patients with RA demonstrated that triple therapy was similar to methotrexate plus biologic DMARD or tofacitinib in controlling disease activity [12]. However, the discontinuation rates of treatment are higher in triple therapy than combination therapy of MTX plus bDMARDs and there is less persistence and adherence [19, 20]. In one study of 3724 patients on etanercept and methotrexate (ETN-MTX) and 818 patients on triple therapy, compared with triple therapy, ETN-MTX was significantly associated with greater adherence (odds ratio 1.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.47 to 2.17) and persistence (odds ratio 1.45, 95% CI 1.20 to 1.72) [21]. The decision to pursue a csDMARD combination therapy versus biologic therapy needs to be balanced against the risk of adverse effects, drug toxicity, access to medications, patient preference, ease of administration, cost, and adherence.

EULAR, at the stage of DMARD monotherapy failure, recommends stratifying patients into those with poor prognostic factors (positive rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, and failure of two or more csDMARDs, high disease activity, early erosions). In the presence of poor prognostic factors, addition of bDMARDs or a tsDMARDs is recommended rather than another csDMARDs. In the absence of poor prognostic factors, either combination of csDMARDs or switching to another csDMARDs (leflunomide, sulfasalazine alone) can be considered. All prognostic markers are not further specified with regard to their measurement thresholds. Furthermore, there is no universally accepted list of prognostic factors in RA and the relative importance of these factors varies among recommendations and clinical studies. The 2012 ACR RA treatment guideline stratified treatment recommendations by presence/absence of prognostic factors, while the current 2015 ACR RA guideline stresses on disease activity measurement and to treat to target, due to a frequent overlap and concordance between these prognostic factors and active RA. Nevertheless, these prognostic factors are often associated with worse disease outcomes as reported by a study from Corrona registry showing less occurrence of low disease activity or remission in patients with greater number of prognostic factors indicating that their presence may imply moderate/high disease activity in which aggressive management with biologics is equitable [22].

Combination therapy

Biologic DMARDs when initiated after csDMARD failure should be used in combination with a csDMARDs whenever possible. MTX is the most well-studied csDMARDs in the combination therapy and is associated with a lower risk of immunogenicity with monoclonal antibody biologic DMARDs [23]. Other csDMARDs can also be used though less robust data are available. Combination therapy offers advantages of superior efficacy than monotherapy with conventional or biologic DMARD alone. In TEMPO, a double-blind, randomized controlled trial (RCT), 686 patients with active RA who had inadequate response to a csDMARDs other than methotrexate were randomly allocated to treatment with etanercept 25 mg (subcutaneously twice a week), oral methotrexate (up to 20 mg every week), or the combination. The ACR response in 24 weeks and primary radiographic endpoint was significantly better in the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with methotrexate or etanercept alone [24]. Similarly, abatacept plus MTX showed more robust efficacy compared with MTX or abatacept alone [25]. In AVERT trial, higher proportion of RA patients with poor prognostic factors (positive rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody) achieved remission with abatacept plus MTX (60.9%) versus MTX alone (45.2%) or abatacept monotherapy (42.5%) [26]. Similar results have been seen with adalimumab [13] and certolizumab [27]. In a large double-blind RCT (FUNCTION) of MTX-naive patients with early RA, tocilizumab monotherapy achieved DAS 28 ESR remission in patients at week 24 similar to combination of tocilizumab with MTX (39 versus 45% of patients) though suppression of structural joint damage was numerically greater in combination with MTX compared with monotherapy at week 52 [28].

Combination therapy is strongly advocated by the guidelines. Real-world data show that one-third of RA patients are receiving biologic monotherapy [29]. A number of factors likely contribute to this scenario, including contraindications, adverse effects, lack of adherence, and persistence to a csDMARDs. Strategies to mitigate adverse effects from csDMARDs such as dose reduction, conversion of oral methotrexate to subcutaneous, and the use of folate with methotrexate may help improve adherence. If monotherapy is to be used, non-TNFi biologics or tsDMARDs can be considered. Tocilizumab monotherapy displayed greater efficacy to adalimumab [30] and may have equal efficacy in comparison with tocilizumab with MTX. A 2015 NMA of 28 RCT of biologics as monotherapy or combination therapy demonstrated that as monotherapy, tocilizumab displayed better clinical efficacy compared with TNFi or tofacitinib [31]. A Cochrane systematic review and NMA of 46 RCT of biologic or tofacitinib monotherapy in 2017 concluded no significant difference [32]. Combination therapy should be favored whenever possible; however, several patient-related factors including comorbidities will impact the final choice of biologic in clinical practice.

Treatment following failure of first biologic DMARDs

If patient’s disease activity fails to respond to initial bDMARDs or tsDMARDs, treatment with another biologic is indicated [32]. Claims data from commercial and Medicaid healthcare plans in the USA show that TNFi are the most commonly used initial biologics after csDMARD failure [33]. However, TNFi is not effective in all RA patients, similar to any other DMARDs. In fact, only 25–42% of patients reach the treatment target of ACR50 response rate with TNFi [34]. Patients who do not respond to biologics can be classified in those who never showed an adequate response (primary non-responders) or those who initially had a response but lost it over the course of time (secondary non-responders) perhaps from development of anti-drug antibodies. Two options are available in these scenarios, switching to alternative TNFi or switching to a bDMARDs with another mode of action. Both guidelines recommend using a biologic with a different mechanism of action over a second TNFi.

The evidence of efficacy of TNFi cycling (sequential use of second TNFi) comes from both uncontrolled studies [35] and controlled RCT. The GO-AFTER trial included patients with RA who had previously received TNFi and showed significantly higher ACR 20 responses with golimumab compared with placebo group [36]. It strengthened the notion that a second TNFi with a different molecular structure may still be effective after initial TNFi failure. Similarly, REALISTIC study [37] and more recent EXXELERATE study proved the efficacy of certolizumab pegol in patients with RA with active disease who have had prior TNFi use [38]. The data supporting a strategy to switch biologics to another mechanism of action are limited. In RA patients from Corrona registry with prior exposure to ≥ 1 TNFi who initiated rituximab or another TNFi, rituximab was associated with an increased likelihood of achieving low disease activity or remission compared with TNFi with comparable adverse effects [39]. Similar results were found in another observational SWITCH RA study in which seropositive (rheumatoid factor) patients had significantly greater improvements in disease activity with rituximab than those with second TNFi [40]. A study from Swedish Rheumatology register compared patients initiating TNFi, rituximab, abatacept, or tocilizumab in 2010–2016 as first bDMARDs (n = 9333), or after switch from TNFi as first bDMARDs (n = 3941). Treatment effectiveness was assessed as the proportion of patients with EULAR Good Response/Health Assessment Questionnaire improvement. Patients receiving non-TNFi in particular tocilizumab and rituximab had better clinical response than TNFi both as first and second biologic [41]. A 52-week multicenter, open-label RCT evaluated a total of 300 patients with RA who had insufficient response to TNFi therapy [42]. These patients were randomized to receive another TNFi or a non-TNFi biologic and the choice of biologic was determined the treating clinician. A total of 69% patients in the non-TNFi group and 52% in the second TNFi group achieved a good or moderate EULAR response (OR, 2.06; 95% CI 1.27 to 3.37; P = 0.004) at week 24. However, this study had limitations with regard to lack of blinding, not allowing certain biologics and lack of power to detect differences in adverse effects. Additionally, the use of wide variety of non-TNFi biologics limited the understanding as to which specific biologic should be used after failure of initial biologic. While both TNFi cycling and switching approaches are considered reasonable after initial TNFi failure, there is lack of direct head to head comparison between them [43]. In patients who are primary non-responders to TNFi, a biologic with a different mechanism of action should be preferred as it is likely that disease activity is dominantly driven by non-TNF pathway in these cases. If patient has persistent disease activity on TNFi monotherapy, addition of csDMARDs can be considered for attaining a better efficacy.

Tapering of RA treatment

Tapering is appealing considering treatment-related adverse effects and financial cost burden but must be weighed against potential harms of tapering such as risk of disease relapses [44,45,46,47,48]. Tapering implies reduction of dose or the frequency of dosing. A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine RCT of bDMARD discontinuation versus continuation showed that discontinuation of bDMARDs lead to an increased risk of losing remission or low disease activity and radiographic progression; however, tapering doses of bDMARDs did not increase the risk of relapse or radiographic progression, even though there was an increased risk of losing remission [49••]. EULAR recommends that if a patient is in “persistent remission,” tapering of glucocorticoids should be done first followed by considering taper of bDMARDs or tsDMARDs. If patient remains in persistent remission, tapering of csDMARDs could be considered. No definition of persistent remission was provided, so we assume that authors might be referring to remission for at least a reasonable period of 6–12 months or longer. The ideal patient profile in which tapering should be considered is not clear. Presence of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies has been linked to higher relapse risk [50]. Tapering should only be considered in patients who are in remission and not with low disease activity. The remission needs to be stable and sustained over time, ideally over a period of at least 6 months. Strict remission criteria such as ACR/EULAR Boolean or CDAI remission criteria should be used as patients may still have active disease with DAS28 criteria [51]. Tapering of treatment should also be a shared decision-making process and patient must be made aware of a possible relapse.

Case 1 continued

Escalation of RA treatment was recommended for active disease. When drug options were discussed, patient expressed hesitancy to do self-injections due to severe needle phobia. She lived 2.5 h away from the clinic location. As a solo owner of her business, she preferred not to take time off for making trips for infusions. Based on patient’s preference to take oral medications, tofacitinib 5 mg twice a day was initiated along with a course of prednisone 15 mg daily, which was tapered off over 4 weeks. At follow-up in 6 months, patient had achieved disease remission on her current regimen.

Case 2 continued

Laboratory evaluation showed positive ANA (1:320 homogenous pattern; previously negative) with negative SSA, SSB, anti-Smith, DsDNA, RNP antibodies, and normal urinalysis, complement, and immunoglobulin levels. Cryoglobulins, hepatitis C antibody, hepatitis B surface antigen, serum protein electrophoresis, and immunofixation tests were negative. Chest radiograph was also negative. Patient was referred to dermatology and they suspected a diagnosis of chilblain lupus. Patient reported that she had been gardening, out in cold without wearing warm footwear. Although cold-induced chilblains were in differential, based on her new positive ANA and temporal association of her symptoms with initiation of adalimumab, drug-induced lupus phenomenon was felt more likely. Patient was advised warming measures, cold avoidance, and adalimumab was stopped, following which her symptoms resolved. Patient was then started on tocilizumab 162 mg every 2 weeks subcutaneously which led disease remission in her case at follow-up.

Management of comorbidities in RA

Case 3

A 59-year-old Caucasian male with seropositive RA for 7 years presented to his rheumatologist for follow-up. The patient reported that he had been feeling well and denied joint swelling or pain. He was taking methotrexate 20 oral weekly, folic acid 1 mg daily, and tocilizumab 162 SQ once weekly. He occasionally used prednisone when he experienced a flare of RA. He smoked 10 cigarettes a day. His father had a history of ischemic heart disease. His blood pressure was 140/86. Examination showed subluxation at metacarpophalangeal joints in hands and mild tenderness in his right wrist. CDAI calculated in the office was 3 consistent with low disease activity. On laboratory evaluation, his total cholesterol level was 202 mg/dl, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level was 42 mg/dl, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level was 160 mg/dl.

Patients with RA have a high burden of comorbid conditions that are either usually related directly to disease activity or as a result of treatment complications. The risk of cardiovascular disease in markedly increased in RA and increases mortality by 50% compared with the general population [52]. The heightened risk is not fully explained by traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors and RA-related systemic inflammation is thought to be contributing to promotion of atherosclerosis. The commonly used cardiovascular disease risk prediction models often underestimate the risk of CVD in RA patients [53]. EULAR recommends a multiplication factor of 1.5 to predict the risk more accurately [54••]. Studies show that controlling RA inflammation reduces the risk of cardiovascular events [55]. Deploying a strategy of “treat to target” is therefore a very important step to mitigate cardiovascular disease risk in this patient population. Clinicians must also emphasize screening and management of traditional cardiovascular disease risk factors including treating hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obesity, dyslipidemia, encouraging smoking cessation, and recommending lifestyle modifications [56]. Medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and glucocorticoids that are known to cause deleterious adverse effects on cardiovascular health should be kept to a minimum.

The interpretation of lipid profile in RA can be complex due to interplay of lipids with inflammation. Therefore, lipid screening should be best done when the disease activity is in remission or at least stable. Systemic inflammation may decrease lipid levels and thus some patients may not receive adequate treatment as their lipid levels may be in “low category” yet they remain at a high risk of CVD [57]. Patients with low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol are particularly at risk of cardiovascular disease, a concept referred to as “lipid paradox” [58]. A recent study explored the burden of subclinical atherosclerosis in RA patients with low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and found that in RA patients not on lipid lowering therapy with LDL-C less than 70 mg/dl, the coronary artery calcium scores were fourfold higher compared with non-RA controls, including the calcium scores associated with CVD events (≥ 100 units) [59]. The authors concluded that in this subgroup of patients, more advanced investigations for CVD risk assessment and primary prevention measures may be needed.

RA treatments increase the lipid levels [60] that raises a question with regard to cardiovascular risk-benefit balance. However, the findings from the ENTRACTE trial suggest that risk of major adverse cardiovascular events with tocilizumab is comparable with that with etanercept and that perhaps these lipid changes are a result of improved inflammation and may not be detrimental to cardiovascular health [61]. In fact, several studies have shown CVD risk improvement with RA treatments. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 observational studies showed a lower risk of cardiovascular events in patients with TNFi compared with csDMARDs, possibly due to a reduction in systemic inflammation [62]. These findings stress on the importance of tight control over disease activity in addition to management of traditional cardiovascular risk factors to prevent poor cardiovascular outcomes in RA patients.

Case 3 continued

Cardiovascular risk assessment was performed using 10-year risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease based on the risk calculator by American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines from 2013 and was noted to be 17.1% which was an intermediate risk category [63]. When his RA was taken into account, the risk increased considerably to 25.6% (after multiplication × 1.5), which then put him in the high-risk category. Lifestyle modification, nutrition counseling, exercise, smoking cessation, treatment for hypertension, and statin therapy were recommended.

Conclusion

Newer advances in the treatment of RA have made remission or low disease activity achievable and have enabled patients to lead a good quality life. To provide optimal care to RA patients, it is important to diagnose it early, initiate DMARD therapy at the time of diagnosis, and achieve disease control with a treat to target strategy. Monitoring of drug related adverse effects should be done regularly, and steps to mitigate those risks should be taken. Patients with RA are at an increased risk of infections including influenza, pneumococcal disease, and herpes zoster, which can be prevented with vaccinations [64]. EULAR recently updated recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with rheumatic diseases, which is available for use by clinicians in addition to recommendations from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [5]. Emphasis must be placed on management of comorbid conditions, which can adversely affect patient’s health. It is often debated whether the primary care physician or the rheumatologist should take the responsibility of managing the comorbid conditions. Given that rheumatologists are likely more familiar with RA disease process and have increased vigilance for comorbidities, they should take the ownership of these issues and actively collaborate with primary care providers. Establishing this partnership is prudent to provide multi-disciplinary care to RA patients while aiming for excellent clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations

- RA:

-

rheumatoid arthritis

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- EULAR:

-

European League Against Rheumatism

- CDAI:

-

Clinical Disease Activity Index

- SDAI:

-

Simple Disease Activity Index

- DAS:

-

disease activity score

- NSAIDs:

-

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- csDMARDs:

-

conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs

- tsDMARDs:

-

targeted synthetic DMARDs

- JAK:

-

Janus kinase

- bDMARDs:

-

biologic DMARDs

- RCT:

-

randomized controlled trial

- NMA:

-

network meta-analysis

- UAB:

-

University of Alabama at Birmingham

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF, van Zeben D, Kerstens PJ, Hazes JM, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(11):3381–90.

Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64(5):640–7.

• Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2016;68(1):1–26 Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis by the American College of Rheumatology.

•• Smolen JS, Landewé RBM, Bijlsma JWJ, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020. 2019 update of the European League Against Rheumatism) rheumatoid arthritis management recommendations.

Furer V, Rondaan C, Heijstek MW, Agmon-Levin N, van Assen S, Bijl M, et al. 2019 update of EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79(1):39–52.

Aletaha D, Smolen JS. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: a review. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1360–72.

Plant MJ, Jones PW, Saklatvala J, Ollier WE, Dawes PT. Patterns of radiological progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: results of an 8 year prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1998;25(3):417–26.

van Nies JA, Krabben A, Schoones JW, Huizinga TW, Kloppenburg M, van der Helm-van Mil AH. What is the evidence for the presence of a therapeutic window of opportunity in rheumatoid arthritis? A systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(5):861–70.

Aletaha D, Funovits J, Keystone EC, Smolen JS. Disease activity early in the course of treatment predicts response to therapy after one year in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(10):3226–35.

van Dongen H, van Aken J, Lard LR, Visser K, Ronday HK, Hulsmans HM, et al. Efficacy of methotrexate treatment in patients with probable rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(5):1424–32.

Genovese MC, Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, et al. Etanercept versus methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year radiographic and clinical outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(6):1443–50.

Hazlewood GS, Barnabe C, Tomlinson G, Marshall D, Devoe DJ, Bombardier C. Methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate combination therapy with traditional and biologic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for rheumatoid arthritis: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;8:CD010227.

Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(1):26–37.

Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, Durez P, Chang DJ, Robertson D, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):375–82.

Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, Curtis JR, Bathon JM, St Clair EW, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis: the treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(9):2824–35.

Verschueren P, De Cock D, Corluy L, Joos R, Langenaken C, Taelman V, et al. Methotrexate in combination with other DMARDs is not superior to methotrexate alone for remission induction with moderate-to-high-dose glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis after 16 weeks of treatment: the CareRA trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):27–34.

Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Ortiz Z, Katchamart W, Rader T, et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000951.

O’Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, Ahluwalia V, Brophy M, Warren SR, et al. Therapies for active rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):307–18.

Erhardt DP, Cannon GW, Teng CC, Mikuls TR, Curtis JR, Sauer BC. Low persistence rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with triple therapy and adverse drug events associated with sulfasalazine. Arthritis Care Res. 2019;71(10):1326–35.

Curtis JR, Palmer JL, Reed GW, Greenberg J, Pappas DA, Harrold LR, et al. Real-world outcomes associated with triple therapy versus TNFi/MTX therapy. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020.

Bonafede M, Johnson BH, Tang DH, Shah N, Harrison DJ, Collier DH. Etanercept-methotrexate combination therapy initiators have greater adherence and persistence than triple therapy initiators with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2015;67(12):1656–63.

Alemao E, Litman HJ, Connolly SE, Kelly S, Hua W, Rosenblatt L, et al. Do poor prognostic factors in rheumatoid arthritis affect treatment choices and outcomes? Analysis of a US rheumatoid arthritis registry. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(10):1353–60.

Jani M, Barton A, Warren RB, Griffiths CE, Chinoy H. The role of DMARDs in reducing the immunogenicity of TNF inhibitors in chronic inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(2):213–22.

Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, de Jager JP, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9410):675–81.

Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, Nayiager S, Wollenhaupt J, Durez P, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(12):1870–7.

Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP, Combe BG, Furst DE, Barré E, et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):19–26.

Atsumi T, Yamamoto K, Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Tanaka Y, et al. The first double-blind, randomised, parallel-group certolizumab pegol study in methotrexate-naive early rheumatoid arthritis patients with poor prognostic factors, C-OPERA, shows inhibition of radiographic progression. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):75–83.

Burmester GR, Rigby WF, van Vollenhoven RF, Kay J, Rubbert-Roth A, Kelman A, et al. Tocilizumab in early progressive rheumatoid arthritis: FUNCTION, a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(6):1081–91.

Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(12):1897–904.

Gabay C, Emery P, van Vollenhoven R, Dikranian A, Alten R, Pavelka K, et al. Tocilizumab monotherapy versus adalimumab monotherapy for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (ADACTA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase 4 trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9877):1541–50.

Buckley F, Finckh A, Huizinga TW, Dejonckheere F, Jansen JP. Comparative efficacy of novel DMARDs as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional DMARDs: a network meta-analysis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21(5):409–23.

Singh JA, Hossain A, Tanjong Ghogomu E, Mudano AS, Maxwell LJ, Buchbinder R, et al. Biologics or tofacitinib for people with rheumatoid arthritis unsuccessfully treated with biologics: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;3:CD012591.

Jin Y, Desai RJ, Liu J, Choi NK, Kim SC. Factors associated with initial or subsequent choice of biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):159.

Johnson KJ, Sanchez HN, Schoenbrunner N. Defining response to TNF-inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: the negative impact of anti-TNF cycling and the need for a personalized medicine approach to identify primary non-responders. Clin Rheumatol. 2019;38(11):2967–76.

Nikas SN, Voulgari PV, Alamanos Y, Papadopoulos CG, Venetsanopoulou AI, Georgiadis AN, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from infliximab to adalimumab: a comparative controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(2):257–60.

Smolen JS, Kay J, Doyle M, Landewé R, Matteson EL, Gaylis N, et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors: findings with up to five years of treatment in the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 GO-AFTER study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:14.

Weinblatt ME, Fleischmann R, Huizinga TW, Emery P, Pope J, Massarotti EM, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol in a broad population of patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results from the REALISTIC phase IIIb study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51(12):2204–14.

Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Combe B, Curtis JR, Hall S, Haraoui B, et al. Head-to-head comparison of certolizumab pegol versus adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year efficacy and safety results from the randomised EXXELERATE study. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2763–74.

Harrold LR, Reed GW, Magner R, Shewade A, John A, Greenberg JD, et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of rituximab versus subsequent anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with prior exposure to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies in the United States Corrona registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:256.

Emery P, Gottenberg JE, Rubbert-Roth A, Sarzi-Puttini P, Choquette D, Taboada VM, et al. Rituximab versus an alternative TNF inhibitor in patients with rheumatoid arthritis who failed to respond to a single previous TNF inhibitor: SWITCH-RA, a global, observational, comparative effectiveness study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):979–84.

Frisell T, Dehlin M, Di Giuseppe D, Feltelius N, Turesson C, Askling J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of abatacept, rituximab, tocilizumab and TNFi biologics in RA: results from the nationwide Swedish register. In: Rheumatology (Oxford); 2019.

Gottenberg JE, Brocq O, Perdriger A, Lassoued S, Berthelot JM, Wendling D, et al. Non-TNF-targeted biologic vs a second anti-TNF drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis in patients with insufficient response to a first anti-TNF drug: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1172–80.

Todoerti M, Favalli EG, Iannone F, Olivieri I, Benucci M, Cauli A, et al. Switch or swap strategy in rheumatoid arthritis patients failing TNF inhibitors? Results of a modified Italian Expert Consensus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(57 Suppl 7):vii42–53.

Tanaka Y, Hirata S, Kubo S, Fukuyo S, Hanami K, Sawamukai N, et al. Discontinuation of adalimumab after achieving remission in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis: 1-year outcome of the HONOR study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):389–95.

Nishimoto N, Amano K, Hirabayashi Y, Horiuchi T, Ishii T, Iwahashi M, et al. Drug free REmission/low disease activity after cessation of tocilizumab (Actemra) Monotherapy (DREAM) study. Mod Rheumatol. 2014;24(1):17–25.

Haschka J, Englbrecht M, Hueber AJ, Manger B, Kleyer A, Reiser M, et al. Relapse rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in stable remission tapering or stopping antirheumatic therapy: interim results from the prospective randomised controlled RETRO study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):45–51.

Emery P, Hammoudeh M, FitzGerald O, Combe B, Martin-Mola E, Buch MH, et al. Sustained remission with etanercept tapering in early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(19):1781–92.

Fautrel B, Pham T, Alfaiate T, Gandjbakhch F, Foltz V, Morel J, et al. Step-down strategy of spacing TNF-blocker injections for established rheumatoid arthritis in remission: results of the multicentre non-inferiority randomised open-label controlled trial (STRASS: Spacing of TNF-blocker injections in Rheumatoid ArthritiS Study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(1):59–67.

•• Henaux S, Ruyssen-Witrand A, Cantagrel A, Barnetche T, Fautrel B, Filippi N, et al. Risk of losing remission, low disease activity or radiographic progression in case of bDMARD discontinuation or tapering in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic analysis of the literature and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):515–22 A systematic analysis of the literature and meta-analysis that demonstrate that tapering of biologic DMARD does not increase the risk of radiographic progression, though there is a risk of losing remission.

Rech J, Hueber AJ, Finzel S, Englbrecht M, Haschka J, Manger B, et al. Prediction of disease relapses by multibiomarker disease activity and autoantibody status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis on tapering DMARD treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(9):1637–44.

Mäkinen H, Kautiainen H, Hannonen P, Sokka T. Is DAS28 an appropriate tool to assess remission in rheumatoid arthritis? Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(10):1410–3.

Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(12):1690–7.

D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743–53.

•• Agca R, Heslinga SC, Rollefstad S, Heslinga M, McInnes IB, Peters MJ, et al. EULAR recommendations for cardiovascular disease risk management in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of inflammatory joint disorders: 2015/2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):17–28 Recommendations on management of cardiovascular disease in patients with RA.

Arts EE, Fransen J, Den Broeder AA, van Riel PLCM, Popa CD. Low disease activity (DAS28≤3.2) reduces the risk of first cardiovascular event in rheumatoid arthritis: a time-dependent Cox regression analysis in a large cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017.

Burggraaf B, van Breukelen-van der Stoep DF, de Vries MA, Klop B, Liem AH, van de Geijn GM, et al. Effect of a treat-to-target intervention of cardiovascular risk factors on subclinical and clinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(3):335–41.

Semb AG, Kvien TK, Aastveit AH, Jungner I, Pedersen TR, Walldius G, et al. Lipids, myocardial infarction and ischaemic stroke in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in the Apolipoprotein-related Mortality RISk (AMORIS) Study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):1996–2001.

Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Roger VL, Fitz-Gibbon PD, Therneau TM, et al. Lipid paradox in rheumatoid arthritis: the impact of serum lipid measures and systemic inflammation on the risk of cardiovascular disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(3):482–7.

Giles JT, Wasko MCM, Chung CP, Szklo M, Blumenthal RS, Kao A, et al. Exploring the lipid paradox theory in rheumatoid arthritis: associations of low circulating low-density lipoprotein concentration with subclinical coronary atherosclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2019;71(9):1426–36.

Jagpal A, Navarro-Millán I. Cardiovascular co-morbidity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a narrative review of risk factors, cardiovascular risk assessment and treatment. BMC Rheumatol. 2018;2:10.

Giles JT, Sattar N, Gabriel S, Ridker PM, Gay S, Warne C, et al. Cardiovascular safety of tocilizumab versus etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2020;72(1):31–40.

Singh S, Fumery M, Singh AG, Singh N, Prokop LJ, Dulai PS, et al. Comparative risk of cardiovascular events with biologic and synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res. 2020;72(4):561–76.

Goff DC, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB, Gibbons R, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2935–59.

Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr, Akl EA, Bannuru RR, Sullivan MC, et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(1):1–25.

Acknowledgments

The views in this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Funding

No direct funding was obtained for preparing this article. Dr. Singh is supported by the resources and use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Birmingham, AL, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Aprajita Jagpal (AJ) declares that she has no conflict of interest. Jasvinder A Singh (JAS) has received consultant fees from Crealta/Horizon, Medisys, Fidia, UBM LLC, Trio health, Medscape, WebMD, Clinical Care options, Clearview healthcare partners, Putnam associates, Spherix, Practice Point communications, the National Institutes of Health, and the American College of Rheumatology. JAS owns stock options in Amarin pharmaceuticals and Viking therapeutics. JAS is on the speaker’s bureau of Simply Speaking. JAS is a member of the executive of OMERACT, an organization that develops outcome measures in rheumatology and receives arms-length funding from 12 companies. JAS serves on the FDA Arthritis Advisory Committee. JAS is a member of the Veterans Affairs Rheumatology Field Advisory Committee. JAS is the editor and the Director of the UAB Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Satellite Center on Network Meta-analysis. JAS previously served as a member of the following committees: member, the American College of Rheumatology’s (ACR) Annual Meeting Planning Committee (AMPC) and Quality of Care Committees, the Chair of the ACR Meet-the-Professor, Workshop and Study Group Subcommittee, and the co-chair of the ACR Criteria and Response Criteria subcommittee.

Role of the Funder/Supporter

The funding bodies did not play any role in design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

IRB Approval

Since this was not a research study, no IRB approval was needed.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jagpal, A., Singh, J.A. Treatment Guidelines in Rheumatoid Arthritis—Optimizing the Best of Both Worlds. Curr Treat Options in Rheum 6, 354–369 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-020-00163-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40674-020-00163-w