Abstract

Lifestyle medicine (LM) offers a unique opportunity to address chronic disease globally. Practitioners are able to provide evidence-based suggestions in a way that supports behavior change. One of the barriers to implementing LM more broadly is the lack of training in this rapidly growing field. To fill this gap in LM education, the authors have created Foundations of Lifestyle Medicine, a freely available online curricular template that can be quickly implemented in a variety of health education settings and timelines. This article provides an overview of the curriculum and a discussion of how it may be implemented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 60% of adults in the USA suffer from chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer. Additionally, 40% of American adults have 2 or more chronic diseases [1]. As a result, chronic diseases are amongst the most prevalent types of conditions graduating medical students will see in their future training and practice, regardless of chosen specialty.

Current western treatment approaches for chronic disease have largely focused on pharmaceuticals or surgical procedures to alleviate the complications that result from the disease itself. While these approaches have been able to reduce mortality from chronic disease significantly and have allowed us to diagnose diseases at an earlier stage, they have fallen short of being able to reduce overall incidence. As such, we have a high prevalence of adults with chronic disease living longer lives, but often with significant disability.

A closer look at the top chronic diseases reveals that these are often lifestyle diseases rather than genetic. In fact, robust data suggests that adopting basic lifestyle behaviors such as diet, exercise, and not smoking reduces the incidence of chronic disease by about 80% [2]. Other data has shown the ability of lifestyle changes to halt the progression of and sometimes to even reverse chronic disease [3,4,5].

Having seen the data, the American Medical Association passed a resolution in 2018 calling for, “…increased lifestyle medicine (LM) education in medical school education, graduate medical education, and continuing medical education, including but not limited to education in nutrition, physical activity, behavior change, sleep health, tobacco cessation, alcohol use reduction, emotional wellness, and stress reduction [6].”

LM, founded in the pillars mentioned above, is a rapidly growing field of medicine that focuses on helping patients to prevent, treat, and even reverse chronic disease using lifestyle measures. LM is grounded in the same scientific rigor that medicine has always used. Its approach is unique in that there is a deeper emphasis on using lifestyle as a treatment as well as a focus on how to work with patients for behavior change. Traditionally, healthcare professionals have been inadequately instructed in basic lifestyle measures such as what is a healthy diet or the benefits of exercise. They have certainly not been trained to work with patients to increase self-efficacy for long-term behavioral change.

Although awareness of matters involved in LM, such as physical activity, sleep, and behavior change, is increasing rapidly, curricula still fall far short of what is needed to adequately provide students with the skills they need in these areas. Despite the overwhelming evidence, medical schools (and board exams) have been slow to incorporate this critical training within the curricula [7]. For example, only about a quarter of medical schools nationally meet the minimum guideline set by the National Academy of Sciences for 25 h of nutrition during undergraduate medical education and analysis of these programs shows a lack of consistency [8,9,10]. The reasons for these deficits are varied and complex. Some that have been identified include difficulty finding space in already packed curriculums, pressure to teach to board exams, and a lack of content expertise [11].

Existing Lifestyle Medicine Curricula

Despite these barriers, the chronic disease crisis as well as the growing evidence base for lifestyle approaches are inspiring healthcare professionals and educators to look for a different approach to medicine. They are working to bring this critical information to our next generation of providers. Additionally, the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM), a national organization dedicated to promoting LM, has been instrumental in constructing standards for LM education and advocating for increased curricula.

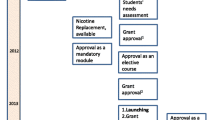

Several pioneers in the field of LM education have already created curriculum which has been shared with ACLM [12,13,14,15]. Each of these curricula, seen in Table 1, fills a specific role in the educational training of healthcare workers.

These materials are a strong start to providing faculty with much-needed resources in teaching LM. However, a comprehensive introduction to LM at the medical student level is not yet available. In this article, we introduce Foundations of Lifestyle Medicine: An introductory curriculum for medical students as an additional resource. This curriculum fills a gap by providing a complete and flexible resource for educators and students alike. The document includes guidance and a suggested schedule for faculty to develop and implement a 2–4 week dedicated medical school elective. Additionally, it consists of discussion questions, activities, experiential learning opportunities, and an abundance of practical clinical tools in addition to instructional content from readings and videos. While the structure provided is geared towards medical students’ clinical training years, the content is also appropriate to use for other healthcare providers in training, such as in nurse practitioner and physician assistant programs.

With this introduction, a bridge is formed to allow students to become LM practitioners early in their careers. Students who are exposed to LM during their formative years already have multiple avenues by which they can become board certified or licensed in this specialty. They can also choose to pursue further training within a residency program, fellowship, or through access to a variety of online resources.

Introduction of Foundations of Lifestyle Medicine (Foundations)

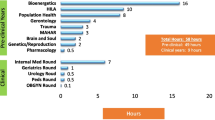

Foundations is composed of 11 sections. It starts by differentiating LM from other approaches and then develops the rationale behind why we need to increase training in this arena. A key to LM is mastering an understanding of behavior change and how to clinically work through that process. As such, the second section is devoted to this topic and provides experiential activities for students to better understand the process and have concrete tools when working with patients. The middle and bulk of the curriculum provides insight into each of the 6 pillars of LM: nutrition, physical activity, restorative sleep, stress management, positive social connection, and avoidance of risky substances. The final part of the curriculum specifically applies LM to the treatment of 3 major chronic diseases in the USA: cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cancer.

Foundations has been created in a modular format so it can meet a variety of educational and structural needs. Within each section, specific learning objectives, discussion questions, resources, and activities are included to facilitate the integration of materials into existing curricula. Articles and videos form the base of curricular materials to allow education to be as asynchronous and as flexible as needed. Specifically, seminal studies and well-respected reviews provide students with a strong foundation in the scientific basis behind LM. Given this is an introductory course, materials also cover the pathophysiological mechanisms rooted in LM. Additionally, clinically oriented articles provide practical information for implementing LM. Discussion questions are derived from didactic materials to assist faculty in exploring concepts further.

Included activities and experiential learning are intended to reinforce concepts reviewed in the readings and videos as well as to add to discussions. Activities specifically introduce learners to helpful clinical tools and engage them in practical tasks such as food label reading, developing skills in culinary medicine and improving motivational interviewing skills. Experiential learning activities ask students to reflect on, measure, and form goals around their own habits. Experiential learning is strongly encouraged as it provides for deeper learning as well as being consistent with the tenet that we as providers must also practice LM if we are to be effective in advocating it for our patients. By asking students to incorporate or try some of these behaviors, we hope to set them up for healthier lifelong habits and increased investment in bringing LM to future patients.

Finally, a separate spreadsheet that characterizes and summarizes the reading material is provided for faculty to gain an overview understanding of information and to assist with curriculum planning. The spreadsheet highlights the findings of each article as well as discusses its significance.

Accessing the Curriculum

The curriculum, including supporting documents, are easily accessible online for free download at https://www.LifestyleMedicineCurriculum.org. Individuals will be asked for their contact details in order to assist the authors with obtaining feedback and revising the document to better meet the needs of educators.

Using the Foundations Curriculum

As mentioned above, this curriculum is specifically written to be as flexible as possible across various settings, timelines, and existing curricula. In terms of settings, it may be used in its entirety within an online format, within a clinical elective, or in a live classroom setting throughout the pre-clinical and clinical years. With regard to timeline, the full curriculum consists of 80 h of material. This could be completed in a full 2-week elective or spread out into 4 or more weeks depending on level of clinical involvement. Additionally, the modules are self-contained so the curriculum may be broken up and inserted as needed into an existing instructional plan to span months or years of training.

It will be easiest to introduce each pillar separately. However, the authors suggest frequently weaving together similar concepts from prior pillars to provide the strongest foundation. Notations have been made within the curriculum to facilitate this process. Finally, a sample schedule is provided that will provide faculty with guidelines on time allocations for activities and how to spread out the material.

For faculty interested in creating an elective, the introduction section of the document outlines a general process that can be used. Planning tips to make the process more efficient are also provided. Topics covered include gaining administrative support, integrating clinical opportunities, and creating a culinary experience with minimal supplies. Finally, resources are provided for the evaluation component of a course.

The available spreadsheet that summarizes the readings is intended to assist faculty in leading discussions that compare the literature as well as to quickly focus in on articles that may be of the most use within existing curricula. Articles are available online to facilitate access for both faculty and learners and are accessible via the spreadsheet as well as via the actual curricular document. The spreadsheet is primarily intended for faculty use only but could be shared at the end of the course to provide students with a succinct summary of notable studies in each LM pillar.

The discussion questions and activities included in this document work best with scheduled live (in-person or online) sessions for discussion and practice. If these are not possible, the questions may be formatted for discussion boards or reflective assignments that can provide a forum for deeper thinking. Most of the activities lend themselves well to partnering with a classmate for a more interactive learning experience. Finally, the experiential activities will be best done when students can partner with each other, especially as they create goals for themselves and work through the process of implementing them. The dialogue generated in helping a classmate through the stages of change as well as being on the receiving end of a behavioral change is particularly instructional in developing patient skills. If this is not possible, alternatives are provided for students to work with a family member or friend.

Some of the experiential activities require students to log their exercise, sleep, diet, or other activities. These are highly recommended as they will provide students with familiarity of apps they can use with patients and skills to meaningfully use the programs. These activities are designed to help students develop strong habits themselves, as well as better understand the process of change at a personal level.

Conclusion

Early exposure to LM is critical to helping students develop their foundational approach to medicine, their role as a provider, and to developing personal habits that support health and resilience. Through LM, students learn not only how to manage chronic diseases but how to actively prevent and at times reverse them.

The Foundations curriculum fills a need for a comprehensive introduction to LM for students in training. We recognize that the design of medical and other healthcare educational programs is varied across the country and that curricula need to be able to mold into a variety of settings. It is our hope that the structure used here will provide the flexibility needed to fill both small and large spaces as the opportunity for LM curricula arises and the interest grows.

In developing this curriculum, it has been our aim to provide faculty with an innovative and practical curriculum that will peak the natural curiosity of students to further explore and apply LM principles in patient care throughout their careers.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention authors. About chronic diseases. In: NCCDPHP. 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kröger J, Schienkiewitz A, Weikert C, Boeing H. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1355–62. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.237.

Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, Brown SE, Gould KL, Merritt TA, Sparler S, Armstrong WT, Ports TA, Kirkeeide RL, Hogeboom C, Brand RJ. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2001–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.280.23.2001.

Esselstyn CB Jr, Gendy G, Doyle J, Golubic M, Roizen MF. A way to reverse CAD? J Fam Pract. 2014;63(7):356–364b.

Gregg EW, Chen H, Wagenknecht LE, Clark JM, Delahanty LM, Bantle J, Pownall HJ, Johnson KC, Safford MM, Kitabchi AE, Pi-Sunyer FX, Wing RR, Bertoni AG, Look AHEAD Research Group. Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2012;308(23):2489–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.67929.

AMA authors. Healthy Lifestyles H425.972. In: American Medical Association Policy Finder. 2023. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/Healthy%20%20Lifestyles%20H-425.972?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-3746.xml. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

Vij V. Integration of lifestyle medicine into the medical undergraduate curriculum. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2022;10(2):133–4. https://doi.org/10.30476/JAMP.2022.93916.1559.

Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med. 2010;85(9):1537–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181eab71b.

Adams KM, Butsch WS, Kohlmeier M. The state of nutrition education at US medical schools. J Biomed Educ. 2015;4:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/357627.

Bassin SR, Al-Nimr RI, Allen K, Ogrinc G. The state of nutrition in medical education in the United States. Nutr Rev. 2020;78(9):764–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuz100.

Trilk J, Elkhider I, Asif I, Buchanan A, Emerson J, Kennedy AB, Masocol R, Motley E, Tucker M. Design and implementation of a lifestyle medicine curriculum in undergraduate medical education. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2019;13(6):574–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1559827619836676.

ACLM authors. Lifestyle Medicine 101 Curriculum. In: The American College of Lifestyle Medicine. https://lifestylemedicine.org/project/lm-101/. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

ACLM authors. Culinary Medicine Curriculum. In: The American College of Lifestyle Medicine. https://lifestylemedicine.org/project/culinary-medicine-curriculum/. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

ACLM authors. Lifestyle medicine residency curriculum. In: The American College of Lifestyle Medicine. https://lifestylemedicine.org/residency-lmrc/. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

ILM authors. Lifestyle medicine education. In: Lifestyle medicine education. http://www.lifestylemedicineeducation.org/. Accessed 2 Oct 2022.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sandefur, K., Bansal, S. Filling the Gap: An Innovative Lifestyle Medicine Curriculum for Medical Students. Med.Sci.Educ. 34, 485–489 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-01985-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-024-01985-2