Abstract

Background

Professionalism is a key competency in first year medical gross anatomy instruction, yet there is a paucity of longitudinal studies addressing professionalism attributes into year 2. This study longitudinally compared 160 preclinical medical students’ peer professionalism evaluations in two small group settings (year 1 anatomy lab and year 2 team-based learning (TBL) sessions) for 2013–2014 and 2014–2015.

Methods

Students were evaluated by their small group peers on a scale (0–3) on five professionalism domains (teamwork, honor/integrity, caring/compassion/communication, respect, responsibility/accountability) at mid-term and end of semester in years 1 and 2. Statistical comparisons were made between the formative (mid-gross) and summative (post-gross) anatomy ratings and between the summative anatomy (post-gross) and mid-term TBL (mid-iTBL) ratings.

Results

Anatomy professionalism evaluations showed a significant increase from an average ranking of 2.49 at mid-term to 2.6 at the end of the semester, with increases in teamwork, honor/integrity, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Summative anatomy evaluations (post-gross) were compared to mid-term second year TBL (mid-iTBL), showing significant increases in peer professionalism rankings with improvements in teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, and respect.

Conclusions

Significant improvements in peer evaluated professionalism were observed in multiple domains over time in the anatomy lab, with the exception of responsibility and accountability. These gains were maintained into year 2 TBL evaluations, with the exception of caring, compassion, and communication, suggesting that graded peer evaluation may improve professionalism behavior in small group settings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Professionalism is a key competency in medical education [1] and its importance is recognized by governing bodies at all levels [2], including the American Association of Medical Colleges [3], the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education [4], and specialty-specific entities such as the American Board of Internal Medicine [5]. Key elements of professionalism for medical professionals in training include altruism, accountability, excellence, honor, integrity, and respect for others [5]. While most medical schools report incorporating professionalism instruction into their formal curriculum [6], it is often taught in isolated courses or clerkships, without continual monitoring and reinforcement or formative feedback provided to students [7]. When professionalism training is not guided or systematic in its delivery, the informal or “hidden” curriculum may negatively impact students’ progress in this realm of their medical education, particularly in third and fourth years of training [8]. Evaluation of professionalism is critical to the longitudinal mission of undergraduate and graduate medical education, as lapses in medical school can be predictive for subsequent professional misconduct in practice [9].

In the undergraduate medical education literature, much attention has been dedicated to studies on professionalism in the first year gross anatomy experience [10,11,12,13,14,15], specifically addressing changes in professional behaviors that may occur during or as a result of the anatomy laboratory experience. Peer evaluation has been well established as a validated method of professionalism assessment both in gross anatomy [11, 15] as well as in other disciplines in medical education [16,17,18]. While the existing literature has provided robust evidence that the gross anatomy laboratory experience affords students the opportunity to make significant gains in their professionalism development, there is a lack of longitudinal data tracking these students beyond first year [19]. The present study describes a longitudinal, graded peer evaluation program that extends over the first 2 years of medical school (preclinical curriculum), tracking changes in various professionalism domains.

Methods

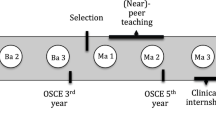

Peer professionalism evaluations were required as a graded activity for medical students from the class of 2017 (n = 160) during the first and second year preclinical curriculum (Fig. 1). In the first year curriculum, the peer evaluations were conducted twice (formatively at mid-term and summatively at the end of the course) based on team interactions in the gross anatomy laboratory. The reciprocal peer teaching model was used in the gross anatomy laboratory [20]. Six students were assigned alphabetically to each dissection group, and each team was divided into two teams of three students (team A and team B). Only one team dissected each day, and these roles alternated with each laboratory session. During the last 30 min of each laboratory, the non-dissecting team returned to the lab for peer teaching of the day’s learning objectives and checklist items. Each team worked together, and peer taught during 19 lab sessions over a 16-week semester (total of 38 labs). Each dissection group member evaluated professionalism for each of their five lab group members, both in teams A and B. In the second year curriculum, the peer evaluations were conducted twice (formatively at mid-term and summatively at the end of the course) based on group interactions in an Integrated Team-Based Learning (i-TBL) course; this second year course was designed to provide a common thread between the Microbiology, Pathology, Pathophysiology, and Pharmacology courses in the second year curriculum. Teams of six second year students were randomly selected (different from the groups in the first year gross anatomy laboratory) and worked together in the traditional team-based learning format during 19 sessions over a yearlong curriculum. Team-based learning requires students to conduct prereading as independent study, followed by an individual readiness assessment test (IRAT), a group readiness assessment test (GRAT), and finally an application exercise to apply the newly gained knowledge in a practical setting [21, 22].

The construct of professionalism was defined as student behaviors characterized across five domains, including teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. A survey was developed at University of Louisville to evaluate each of these professionalism parameters in both the gross anatomy laboratory and in iTBL (Appendix 1). Each professionalism domain was evaluated by peers on a scale from 0 to 3, with 3 indicating “advanced,” 2 indicating “competent,” 1 indicating “needs improvement,” and 0 indicating “unacceptable,” with a specific rubric provided for each. The results were aggregated, de-identified, and returned to students so that they could read feedback on their performance to date in the course. Students were graded by the course director on their behavior as evaluators, and additional credit was added or subtracted from the grade awarded by their peers based on timeliness of survey completion, presence of grade variability between students they evaluated, and specificity and helpfulness of constructive criticism comments. Grade variability was required of each student when they evaluated their team members, such that students did not simply award full credit to all team members automatically; in the event that a student believed that a team member deserved full credit in all professionalism domains, the comments provided had to be specific enough to justify this grade when reviewed by the course director. In both the gross anatomy and iTBL courses, the professionalism evaluations were worth 5% of the total grade. There was no discernible difference between the two course directors with respect to grading of students’ professionalism evaluations.

SPSS (2013) version 22.0 was used to analyze the quantitative data. The averaged peer evaluations of the Likert-scaled response format items of teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect along with the overall average of these five items were compared among students’ formative and summative gross anatomy evaluations, as well as students’ formative and summative iTBL evaluations using paired sample t tests. Analysis using the paired sample t test is justified as examination of the peer evaluation difference among the different time points showed the distributions to be relatively normal. All p values were two tailed. Since six multiple t tests were performed on each item, the type I error rate could be inflated. Therefore, the Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the conventional statistical significance level of p ≤ 0.05 to p ≤ 0.008.

An expedited review was conducted for this study (IRB number 15.0150), and ethics approval was granted on March 3, 2015 from the University of Louisville Institutional Review Board. The data was collected as part of the standard medical curriculum in first and second year of medical school. Consent forms were not obtained, but a preamble that explained the purpose of the study was e-mailed to the subjects. Subjects were given the opportunity to opt of the study by responding to research coordinator via e-mail.

Results

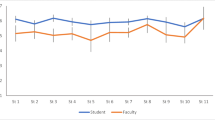

One-hundred-and-fifty students (93.8%) from the class of 2017 agreed to let their data be used in this study. Initially, the scores for all professionalism domains were averaged to yield a mean score for each time point measured (mid-term and end of course for gross anatomy and for iTBL). These time points are designated as “mid-gross,” “post-gross,” “mid-iTBL,” and “post-iTBL.” Significant gains in overall professionalism scores were observed (Fig. 2) when comparing formative and summative gross anatomy evaluations (p < 0.001), summative gross anatomy, and mid-term iTBL evaluations (p = 0.003) as well as formative and summative iTBL evaluations (p = 0.007). Significant changes were observed in specific professionalism domains when comparing results from the various time points. First, in looking at changes from formative to summative evaluations in gross anatomy (Fig. 3), gains occurred in teamwork, honor/integrity, caring/compassion/communication, and in respect (p < 0.001). Additional progress was made in transitioning from gross anatomy to iTBL, with significant gains in honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, and respect occurring from the summative gross anatomy to the mid-term iTBL evaluations (Fig. 4). Teamwork scores declined from summative gross anatomy to mid-term iTBL evaluations (p < 0.05). During the iTBL course, gains were observed in teamwork (p < 0.001) and caring/compassion/communication (p = 0.001) between the formative to the summative evaluations (Fig. 5). Finally, comparison of each professionalism domain between the formative gross anatomy and summative iTBL evaluations, looking at overall professionalism development over the first 2 years, yielded significant gains in all dimensions (Fig. 6).

Overall peer professionalism scores for the four time points measured (mid-gross occurred at the mid-term of the fall of first year, post-gross occurred at the end of the fall of the first year, mid-iTBL occurred at the mid-term of fall of second year, post-iTBL occurred at the end of the spring of second year). Error bars represent standard deviations. N = 150 students

Analysis of scores for five peer professionalism domains during first year gross anatomy. Peer evaluations were conducted at mid-term (mid-gross) and at the end of the semester (post-gross). The five domains included teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Each of these domains was scored from 0 (unacceptable) to 3 (advanced). Error bars represent standard deviations. N = 150 students

Analysis of scores for five peer professionalism domains from the end of gross anatomy in year 1 (post-gross) to the mid-term of iTBL in year 2 (mid-iTBL). The five domains included teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Each of these domains was scored from 0 (unacceptable) to 3 (advanced). Error bars represent standard deviations. N = 150 students

Analysis of scores for five peer professionalism domains during second year iTBL course. Peer evaluations were conducted at mid-term (mid-iTBL) and at the end of the semester (post-iTBL). The five domains included teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Each of these domains was scored from 0 (unacceptable) to 3 (advanced). Error bars represent standard deviations. N = 150 students

Analysis of scores for five peer professionalism domains from the mid-term of first year (mid-gross) to the end of second year (post-iTBL). The five domains included teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Each of these domains was scored from 0 (unacceptable) to 3 (advanced). Error bars represent standard deviations. N = 150 students

Discussion

A limited number of studies in the literature have addressed peer professionalism measures in either preclinical or clinical medical students, often through the identification of peer professionalism exemplars through a nomination process [23,24,25,26,27]. One recent study by Emke et al. describes professionalism evaluations in the preclinical curriculum during second year, using multisource feedback through paired self- and peer evaluations [28]. While these studies provide some insight into the reliability of professionalism measures at specific time points along the medical curriculum, little is known about the longitudinal growth in preclinical medical student professionalism over time. The present study demonstrated significant and incremental longitudinal gains in peer professionalism measures over the first 2 years of medical school, specifically in the first year gross anatomy and the second year integrated team-based learning courses. Previous work has documented professionalism gains within a gross anatomy course [13, 29,30,31], but this is the first study that has extended this type of longitudinal analysis into the second year of preclinical training. Our data suggest that peer assessment of professionalism can provide effective formative feedback, giving rise to gains that are stable over time, even in different small group settings. We measured gains in teamwork during gross anatomy and the iTBL course; when comparing the summative anatomy scores with the mid-term iTBL scores, however, there was a significant decrease in teamwork scores, likely due to students adjusting to the transition between working in anatomy dissection teams to team-based learning groups. Gains in the honor/integrity domain were observed during gross anatomy and into the mid-term iTBL evaluation, but these improvements plateaued during iTBL, consistent with the findings of Camp et al. [13]. The responsibility/accountability domain remained unchanged during gross anatomy and during iTBL, but a significant gain was observed between the summative anatomy evaluation and the mid-term iTBL evaluation, likely due to students adjusting to new groups in the team-based learning setting in second year. In addition, medical students have a high baseline for responsibility/accountability, and thus, there may not be significant capacity for growth and improvement in this area. The caring/compassion/communication domain was increased during anatomy and during iTBL, with no significant difference between the summative anatomy evaluation and the mid-term iTBL evaluation, likely due to students adjusting to the transition in small group identity and dynamic between anatomy dissection teams and team-based learning groups. Finally, significant gains were observed in respect during anatomy and between the summative anatomy evaluation and the mid-term iTBL evaluation, but no difference was detected between the two evaluations in iTBL, again consistent with the findings of Camp et al. [13].

The strengths of this study include the longitudinal tracking of peer professionalism data over the preclinical years of medical training, along with the ability to discriminate between five discrete domains of professionalism. The primary limitations of this work include data collection from a single class at a single institution. In addition, professionalism measured from year 1 to year 2 took place in two distinct courses, including the gross anatomy laboratory in year 1 and in a lecture-based, team-based learning setting in year 2. Although the course directors for each class worked to ensure comparability in grading of the students’ peer evaluations, several variables may have influenced the students’ peer evaluation process between the two courses, including different subject matter, course format, group interaction format, and/or team members. Further research is needed to determine whether preclinical professionalism gains as measured by peer evaluations are maintained into the clinical clerkship and acting intern experiences in third and fourth years.

Conclusions

This student cohort demonstrated statistically significant peer professionalism gains in five domains across the first 2 years of medical school, including teamwork, honor/integrity, responsibility/accountability, caring/compassion/communication, and respect. Our results demonstrate that gross anatomy and iTBL experiences may promote professionalism in first and second year medical students prior to entering their clinical clerkships.

References

Shrank W, Reed V, Jernstedt C. Fostering professionalism in medical education: a call for improved assessment and meaningful incentives. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:887–92.

Members of the Medical School Objectives Project. Learning objectives for medical student education- guidelines for medical schools: report I of the medical school objectives project. Acad Med. 1999;74:13–8.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements. [downloaded 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_07012015.pdf.

Members of the Medical Professionalism Project. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6.

Lachman N, Pawlina W. Integrating professionalism in early medical education: the theory and application of reflective practice in the anatomy curriculum. Clin Anat. 2006;19:456–60.

Swick H, Szenas P, Danoff D, Whitcomb M. Teaching professionalism in undergraduate medical education. JAMA. 1999;282:830–2.

Kao A, Lim M, Spevick J, Teaching BB. Evaluating students’ professionalism in US medical schools. JAMA. 2003;290:1151–2.

Bandini J, Mitchell C, Epstein-Peterson Z, Amobi A, Cahill J, Peteet J, Balboni T, Balboni M. Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum: how does the hidden curriculum shape students’ medical training and professionalization? Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017;34:57–63.

Yates J, James D. Risk factors at medical school for subsequent professional misconduct: multicenter retrospective case control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2040.

Escobar-Poni B, Poni E. The role of gross anatomy in promoting professionalism: a neglected opportunity. Clin Anat. 2006;19:461–7.

Swartz W. Using gross anatomy to teach and assess professionalism in the first year of medical school. Clin Anat. 2006;19:437–41.

Pearson W, Hoagland T. Measuring change in professionalism attitudes during the gross anatomy course. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:12–6.

Camp C, Gregory J, Lachman N, Chen L, Juskewitch J, Pawlina W. Comparative efficacy of group and individual feedback in gross anatomy for promoting medical student professionalism. Anat Sci Educ. 2010;3:64–72.

Wittich C, Pawlina W, Drake R, Szostek J, Reed D, Lachman N, et al. Validation of a method for measuring medical students’ critical reflections on professionalism in gross anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6:232–8.

Spandorfer J, Puklus T, Rose V, Vahedi M, Collins L, Giordano C, et al. Peer assessment among first year medical students in anatomy. Anat Sci Educ. 2014;7:144–52.

Alakija P, Lockyer J. Peer and self-assessment of professionalism in undergraduate medical students at the University of Calgary. Can Med Ed J. 2011;2:65–72.

Papinczak T, Young L, Groves M, Haynes M. An analysis of peer, self and tutor assessment in problem based learning tutorials. Med Teach. 2007;29:122–32.

Speyer R, Pilz W, Van Der Kruis J, Brunings J. Reliability and validity of student peer assessment in medical education: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2011;33:572–85.

Jones T. Creating a longitudinal environment of awareness: teaching professionalism outside the anatomy laboratory. Acad Med. 2013;88:304–8.

Krych A, March C, Bryan R, Peake B, Pawlina W, Carmichael S. Reciprocal peer teaching: students teaching students in the gross anatomy laboratory. Clin Anat. 2005;18:296–301.

Michaelsen L, Parmelee D, McMahon L, Revine R. Team-based learning for health professions education: a guide to using small groups for improving learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing; 2008.

Michaelsen L, Richards B. Drawing conclusions from the team-learning literature in health-sciences education: a commentary. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17:85–8.

Finn G, Sawdon M, Clipsham L, McLachlan J. Peer estimation of lack of professionalism correlates with low conscientiousness index scores. Med Educ. 2009;43:960–7.

Hojat M, Michalec B, Veloski JJ, Tykocinski ML. Can empathy, other personality attributes and level of positive social influence in medical school identify potential leaders in medicine. Acad Med. 2015;90:505–10.

McCormack WT, Lazarus C, Stern D, Small PA. Peer nomination: a tool for identifying medical student exemplars in clinical competence and caring, evaluated at three medical schools. Acad Med. 2007;82:1033–9.

Pohl CA, Hojat M, Arnold L. Peer nominations as related to academic attainment, empathy, personality and specialty interest. Acad Med. 2011;86:747–51.

Emke AR, Cheng S, Chen L, Tian D, Dufault C. A novel approach to assessing professionalism in preclinical medical students using multisource feedback through paired self- and peer evaluations. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29:402–10.

Kavas M, Demiroren M, Kosan A, Karahan S, Yalim N. Turkish students’ perceptions of professionalism at the beginning and end of medical education: a cross-sectional qualitative study. Med Educ Online. 2015;20:26614.

Youdas J, Krause D, Hellyer N, Rindflesch A, Hollman J. Use of individual feedback during human gross anatomy course for enhancing professional behaviors in doctor of physical therapy students. Anat Sci Educ. 2013;6:324–31.

Pawlina W, Hromanik MJ, Milanese TR, Dierkhising R, Viggiano T, Carmichael S. Leadership and professionalism curriculum in the gross anatomy course. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2006;35:609–14.

Bryan R, Krych A, Carmichael S, Viggiano T, Pawlina W. Assessing professionalism in early medical education: experience with peer evaluation self evaluation in the gross anatomy course. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2005;34:486–91.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the School of Medicine Class of 2017 for their participation in the peer professionalism evaluation study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Prior Presentation

A preliminary version of this study was presented as a platform presentation at the 2015 annual meeting of the American Association of Clinical Anatomists.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brueckner-Collins, J., Klein, P., Ziegler, C. et al. Tracking Peer Professionalism Measures in Preclinical Medical Students. Med.Sci.Educ. 28, 503–513 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0578-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-018-0578-6