Abstract

The flipped classroom has garnered significant attention in medical education as a model to better promote student learning outcomes as well as student and faculty perceptions. As a pedagogical approach, the flipped classroom requires students to learn foundational material prior to class so that class time can be spent applying that material through active learning. Collectively, we accrued experience with this model, including facing challenges during the design, implementation, and evaluation of courses. This monograph focuses on common challenges faced and recommendation for solving problems that may occur during its utilization based on experience and scholarship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

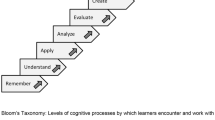

In the flipped classroom, out-of-class self-paced or self-directed learning supports in-class higher-order learning [1,2,3]—essentially reversing the traditional class/homework process. This instructional approach allows students to come to class prepared in terms of foundational knowledge which can yield more impactful learning [4]. Student learning is further enhanced because instructors can then utilize class time more effectively in drawing on these foundations to focus on patient care or more contextualized applications.

The flipped classroom approach has been around in various forms for numerous years. Over this time, various challenges and solutions have been experienced by the practitioners of this model. The purpose of this article is to summarize some of the common challenges and provide corresponding recommendations. As instructors gain more experience with the flipped classroom, the academy can gain a better understanding of common problems and potential solutions—both of which may not necessarily appear in scholarly articles but in hallway conversations or sharing at local and national meetings.

Common Challenges and Solutions Encountered

Each form of pedagogy has potential benefits and drawbacks. The following section describes several of these challenges to the flipped classroom, along with possible solutions:

“I have too much content to cover so I can’t use the flipped classroom.”

This is a common statement with most active learning or engaged learning paradigms [5]. The rate at which information is generated, especially in health care, makes it impossible to cover everything and necessitates educators to weed less relevant topics out of courses. This weeded-out content is replaced by a more in-depth exploration of highly relevant topics and building skills to better ensure life-long learning. One solution in selecting content would be to ask yourself three key questions: (1) What content should students learn that is clinically relevant, and essential for success in subsequent courses and learning experiences?, (2) What knowledge and skills do students need our help to learn and what can they look up and learn on their own?, and (3) What actions can I take in the course that optimizes the opportunities for students to master the learning outcomes of our courses? This process is followed by reviewing the learning outcomes for each session and ensure each objective is clearly defined. The goal is to use benefits of the flipped model (e.g., higher-order learning, development of interpersonal skills) to accomplish the learning goals of the course [6]. Identifying clear learning goals for the course can ensure that the instructional model is appropriate and that other elements of the class (e.g., assessment methods, collaboration work, instructional strategies) are adequately aligned. It is imperative to be mindful that a curriculum is a roadmap for learning and individual courses are part of that roadmap. As such, a school’s curriculum committee or related group may want to play a larger role in determining course-level outcomes and the links between courses, programmatic outcomes and accreditation standards. While your course may not cover all that you may want, the curriculum, through classes and experiential, will cover a very large portion.

“Students need to read this book chapter before class but they don’t do it!”

Moving student learning prior to class requires instructors to select and prioritize key foundational content [7]. Pre-class content should include key definitions and concepts while in-class activities should emphasize higher-order aspects. For example, pre-class content for a pharmacology course might include overview of receptors (e.g., beta-receptors) or physiology (e.g., sympathetic effects) or a therapeutics class might include a review of the organ system (e.g., the heart) and pathophysiology (e.g., arrhythmia). Class time can then be used for clinical application building upon this foundational content. Further, pre-class material that takes too long to complete may discourage students from fully preparing for class. Conversely, material too brief may fail to deliver key information. To promote pre-class preparation, remember RAISE (i.e., Reason, Accountability, Interaction, Student-friendly, and Efficient) [8, 9]. There should be an explicit, transparent, and incentivized reason for having students prepare for class. If students do not see it, the paradigm is less successful [10, 11]. Medical students have various time commitments and their time is spent on what is valued or associated with reward. In a class, points are the reward so hold students accountable by assigning points for pre-class completion. This can be quizzes, cases, submitting outlines, etc. Next, design activities that help students interact with the material, such as answering a pre-class clinical case designed so that students need to acquire the knowledge from the assigned reading to answer questions linked to the case. This strategy could be like that used in just-in-time teaching where students answer a case prior to class and their answers are used to drive class time [12, 13]. The material you assign should also be student-friendly. Most textbooks are written by experts for experts and may not be suitable material for pre-class learning by novices [14]. Finally, make material efficient. Students are under time pressures, just like faculty, so we must design material that delivers the foundational content in an efficient manner. Table 1 includes some recommendations and guidelines

“I don’t know what to do in class if students are learning the information ahead of time.”

Choices for designing and operationalizing a flipped model abound, with new technologies, activities, and strategies, are continuously emerging [7]. While research describes a wide range of successful approaches, selecting appropriate modalities for pre- and in-class engagement is not trivial [7]. Instructors can develop their own active learning exercises or choose from a wide range of published strategies [18,19,20,21]. As a starting point, it may be helpful to begin with strategies that are intuitive and comfortable; case studies, for example, are common and well-described in health professions education [22] along with cooperative learning techniques [23] (e.g., think-pair-share, jigsaw, brainstorming). Regardless of the approach, the planning and design phase of these activities can require significant time (an estimated 10 h to build every 1 h of class) and ongoing refinement [7]. Consider making efforts (e.g., formative assessment) to determine how well-suited new class activities are and to inform improvements moving forward. While it does require investment of time on the front end, a sustainable flipped model can last years unless your field is constantly changing.

“When facilitating class, I get anxiety because I feel I might lose control of the class.”

The sensation or anxiety of losing control of a class discussion is common to active learning [5]. These can be overcome with experience, clarifying expectations, and upfront planning [24]. With experience, we gain some comfort with the unknown—unknown student questions or how cases or discussions will play out. For new instructors, starting with more familiar content may make facilitation easier since there is a larger familiarity and knowledge base. There always will be questions or unplanned situations. Sometimes these can be the most valuable learning experiences to students because they can see how an expert thinks through a situation. One of the most important aspects is upfront expectations which can include amount of time spent on a task or what signals will be used to bring that discussion back to the group if small groups are working (e.g., bell, raising of hands). Finally, up front planning can help with anticipating road blocks. Whether the class has 5 people or 500, an instructor can maintain a controlled discussion.

“I never have enough time in class to cover everything, so I have to lecture.”

In general, faculty tends to underestimate the average amount of time students need to learn new material before class. Since the flipped classroom necessitates learning prior to class, faculty must be thoughtful about the time expectations placed on students and remember that learning can take approximately 2–3 times longer than simply watching a video or reading a text [14, 25]. If the pre-class learning takes an unreasonable amount of time, students are likely to show up unprepared for actively engaging in the classroom. As a common rule of thumb, all out of class activities should require no more than 2 h per 1 h of class time, with videos limited to about 20–30 min each [10, 26]. In addition, chunking material into smaller independent units can help students’ self-regulate learning [27, 28].

Furthermore, managing time in-class is largely a function of the active learning strategies, which may require more time than expected to implement [29]. When planning for class, account for a time cushion as active learning may take more time than expected. Class activities also tend to require facilitation skills to manage the chaos of active learning and engagement. Be mindful of the need to balance between moving class along and spending sufficient time discussing the material or activity.

“Students don’t seem engaged—they are spending time on social media rather than engaging in class activities.”

A common problem in any engaged classroom is student participation. In the flipped classroom design, accounting for student preparation prior to class and for student dispositions toward various learning activities in class may help promote engagement. First, students must be equipped with foundational knowledge and prepared to engage during class. Holding students accountable for learning pre-class material using a quiz or other assignment (e.g., case reports) may encourage them to prioritize the pre-class material appropriately. In one study, students who did not access pre-class material participated less and performed poorer than those that did [30]. In addition, self-paced instructional materials were viewed by 20% of students prior to the first lecture, 42% prior to the second lecture, and 78% prior to the exam. Most students (69%) reported graded assignments as the best incentive for preparing for class [31]. Ensuring that class time is active and applied (as opposed to re lecturing pre-class material or lecturing new material) may further encourage students to participate. Second, there are a variety of “types” of students who may be reluctant to engage in discourse during an average class session, including students who tend to be introverted or shy [32,33,34,35].

Communicating expectations for engagement and creating a safe classroom community that gives time for students to talk to one another, respond to questions, and formulate questions in a discussion may help foster wider student involvement [2, 36]. To ensure accountability by all groups as opposed to a single individual, faculty could advocate simultaneous group responses to questions asked. This is particularly suitable if colored response cards are used but also relevant when using an audience response system (e.g., Poll Everywhere). This could avoid singling out a less engaged learner which is common practice in lectures but rather promote further discussion between groups when explaining and defending their answer choice. On a broader scale, recognize the importance of peer mix and potential pre-existing conflicts between learners, which could hinder engagement [37, 38]. Cooperative learning techniques may be an effective way to promote engagement [39]. In cooperative learning, the first step is individual accountability. This gives the unprepared time to prepare and the introverted time to think and formulate. The second step is smaller group discussion. This allows the shy individuals to test their ideas prior to exposing those ideas to the larger class and potentially allows everyone to speak instead of the most vocal.

“Flipped classes mean we do homework in class, right? So I don’t need to give more homework!”

Flipped courses have been associated with moving homework inside of class time and moving the typical in-class lecture prior to class. As such, some instructors may feel that because students applied the material during class they do not need further application opportunities. Learning does not end when class ends. After a class period, students might spend approximately 1 h on study or additional practice. Providing students with opportunities to further learn and apply material can promote deeper learning and may take the form of traditional homework assignments, papers, or projects [40, 41]. These practices should be spaced and increase in complexity over time to maximize long-term retention [42,43,44].

“I tried the flipped classroom once but students didn’t perform better.”

Some instructors are willing to dismiss the flipped classroom after one attempt. From experience, a flipped or engaged class may not be perfect the first time but if thoughtfully planned, should still be good as the best lecture, if you are to believe the literature about active learning [21, 45,46,47,48]. Why might students not perform better? One reason may be that assessments designed for a lecture-based course are no longer appropriate for an engaged learning paradigm. Literature suggests that the variety and frequency of assessments tend to increase in flipped classrooms while also prompting educators to re-think established approaches to assessment [49]. Focused attention on higher-order cognitive skill development requires assessments that reflect student growth in more complex reasoning skills, such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. In addition, instructors should consider diversifying assessment approaches to more fully evaluate progress toward desired outcomes [50,51,52,53,54]. Various assessment strategies can be built into pre-class material, in-class activities, and post-class practice to provide critical information to the instructor about the efficacy of the class and to the student about mastery of content and key concepts. In-class activities, for example, may be designed to provide real-time feedback to instructors concerning common misconceptions in student knowledge that can immediately be addressed with a short lecture or explanation [55, 56]. Further, advances in technology empower our ability to design and implement various approaches to assessment, including but not limited to embedded self-assessments in pre-class materials, wikis, and discussion forums [6]. Since assessment strategies that target higher-order thinking may require more time and resources to administer (e.g., essays, presentations, projects, or test questions that extend beyond multiple choice items), consideration should be given to the availability of teaching assistants or senior students to help support the commitment required for complex and diverse assessment strategies in the flipped classroom. Taking measurable and strategic steps toward building a diversified assessment plan that is aligned with desired course outcomes can provide critical insight into student outcomes and course functionality.

“Students tell me they pay money to be taught, not to learn in their own or they think it takes more time.”

Another challenge faculty may face is students’ misconceptions of flipped learning. Students may believe, for example, that flipped course require more time or they are doing all the work. Yes, some students may view it as more work with less reward. If planned well, the flipped classroom should not be more work but a simple reallocation of time. Instead of spending time preparing for an exam, less time is needed because the student has been preparing all along. In addition, students tend to look at short-term goals versus long-term goals [57]. If students are focused on course grades and not the ability to retain and use information at some later date, then yes, the flipped classroom may not compare well. Showing students why the approach is taken can be helpful in this respect. Addressing issues up front about time and effort can help alleviate some of the issues. In addition, in the traditional lecture method, students are still doing all the work. They are studying outside of class in response to the lecture material. In the flipped, they are learning on their own first and it is being reinforced in class.

“I need someone to tell me exactly what to do. Isn’t there only one way to flip a class?”

Descriptions of the flipped classroom vary widely, as the model allows for considerable flexibility in operationalization of pre-class, in-class, and post-class activities as well as assessment strategies [7, 11]. While challenges associated with the core elements of the flipped classroom are described above, common design considerations can overlap across these elements, including the following:

Planning

Designing or redesigning a course can require resources and commitment. Prior to the course, desired learning outcomes should be identified, assessments written addressing the learning outcomes, in-class activities planned, and pre-class content selected and packaged to facilitate the in-class activities. Faculty commonly underestimates the time, skill, resources, technology, and collaboration that may be necessary to successfully flip a course.

Constructive Alignment

Constructive alignment provides a framework for instructional design, namely starting with the clear definition of objectives and ensuring that learning activities are aligned to achieve the desired outcomes [6]. In the context of the flipped classroom, this approach can fully support high level learning outcomes with consideration of desired course outcomes and content delivery, creation of learning activities, use of technology, and development of assessments. To aid alignment, some build a table that lists each learning outcome, where it is assessed, what occurs before and in-class to promote its achievement, and what support materials are needed (see Appendix Table 2).

Collaborative Alignment

Team-taught courses introduce unique complexities in the flipped classroom. Instructors may need to sync their approaches with one another to function effectively as team members and enable students to transition smoothly from one topic or class period to another [10]. Course directors in team-taught courses may need additional support for generating buy-in and consistency among instructors in operationalizing the flipped model.

Communication

While instructors may need ongoing support and resources, students may also require assistance transitioning from instructor-centered to learner-centered environments [58]. Some students may be new to the flipped format, so providing clear expectations for pre-class work, in-class engagement, and tips for studying and staying current with the material may be necessary. In addition, students should be provided opportunities to communicate concerns or challenges, including their ability to balance the course workload.

Continuous Quality Improvement

It is unlikely that the first offering of a flipped course will go smoothly and, as with any course design, it may require ongoing adjustments and improvements. Creating mechanisms for generating data can facilitate an iterative design process. In addition, ensuring that course evaluation questions reflect the core elements of the course will improve the quality and usefulness of evaluation results.

Closing Comments

Educators may face many challenges during the process of transitioning from a passive learning environment to a flipped learning environment. We appreciate that a wide range of flipped models are described in the literature and recommend that educators use careful thought and planning when deciding to flip a classroom. We must appreciate what it is like to be a learner and consider how dynamic learning environments can impact the student journey. Experiment and employ rigorous methodology and evaluation methods, use designs that will promote long-term student gains, and foster environments the promote inclusiveness and access. Above all, report not just positive findings but disseminate situations where challenges were experienced. Further understanding and developing flipped models is crucial for optimizing outcomes and ensuring that the model remains flexible, transferable, and relevant.

References

Sharma N, Lau CS, Doherty I, Harbutt D. How we flipped the medical classroom. Medical Teacher. 2015;37(4):327–30. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159x.2014.923821.

McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, Gharkholonarehe N, Davidson CA, Griffin LM, et al. The flipped classroom: a course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):236–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000086.

Persky AM, Dupuis RE. An eight-year retrospective study in “flipped” pharmacokinetics courses. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(10):190. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe7810190.

Shing YL, Brod G. Effects of prior knowledge on memory: implications for education: prior knowledge, memory, brain, and education. Mind, Brain, and Education. 2016;10(3):153–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12110.

Bonwell CC, Eison JA. Active learning: creating excitement in the classroom. ASHE-ERIC higher education report, vol 1, 1991. Washington, DC: School of Education and Human Development, George Washington University; 1991.

Biggs J. Enhancing teaching through constructive alignment. High Educ. 1996;32(3):347–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00138871.

Moffett J. Twelve tips for “flipping” the classroom. Med Teach. 2015;37(4):331–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.943710.

Preparing for class [database on the Internet]2014. Available from: http://learn.pharmacy.unc.edu/education/. Accessed: June 2017.

Shaffer K, Colbert-Getz J. Best practices for increasing reading compliance in undergraduate medical education. Academic Medicine. 2017;Publish Ahead of Print. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001729.

Khanova J, Roth MT, Rodgers JE, McLaughlin JE. Student experiences across multiple flipped courses in a single curriculum. Med Educ. 2015;49(10):1038–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12807.

Persky AM, McLaughlin JE. The flipped classroom—from theory to practice in health professional education. Am J Pharm Ed accepted.

Kraft A, Carter T, editors. Just-in-Time Teaching (JiTT) Applied To Pathology Residency Training 2015; New York: Nature Publishing Group.

Novak GM. Just-in-time teaching. New Dir Teach Learn. 2011;2011(128):63–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.469.

Persky A. Qualitative analysis of animation versus reading for pre-class preparation in a “flipped” classroom. J Excel College Teach. 2015;26(1):5–28.

Rowland M, Tozer TN. Clinical pharmacokinetics: concepts and applications. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995.

DiPiro JT. Pharmacotherapy: a pathophysiologic approach. 8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical; 2011.

Ritzhaupt AD, Barron A. Effects of time-compressed narration and representational adjunct images on cued-recall, content recognition, and learner satisfaction. J Educ Comput Res. 2008;39(2):161–84. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.39.2.d.

Angelo TA, Cross KP. Classroom assessment techniques: a handbook for college teachers. 2nd ed. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1993.

Barkley E. Student engagement techniques: a handbook for college faculty: Wiley; 2009.

Gleason BL, Peeters MJ, Resman-Targoff BH, Karr S, McBane S, Kelley K, et al. An active-learning strategies primer for achieving ability-based educational outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(9):1.

Graffam B. Active learning in medical education: strategies for beginning implementation. Med Teach. 2007;29(1):38–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590601176398.

Srinivasan M, Wilkes M, Stevenson F, Nguyen T, Slavin S. Comparing problem-based learning with case-based learning: effects of a major curricular shift at two institutions. Acad Med. 2007;82(1):74–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ACM.0000249963.93776.aa.

Barkley EF, Major CH, Cross KP. Collaborative learning techniques: a handbook for college faculty. Second edition. ed. The Jossey-Bass Higher and Adult Education series. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley; 2014.

Davis BG. Tools for teaching. 2nd ed. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

Persky AM, Hogg A. Influence of Reading Material Characteristics on Study Time for Pre-Class Quizzes in a Flipped Classroom. Am J Pharm Ed. 2017;81(6):Article 103.

Persky AM, Pollack GM. Transforming a large-class lecture course to a smaller-group interactive course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(9):170. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7409170.

Doolittle P. The effects of segmentation and personalization on superficial and comprehensive strategy instruction in multimedia learning environments. J Ed Multimed Hypermed. 2010;19(2):159.

Doolittle PE, Bryant LH, Chittum JR. Effects of degree of segmentation and learner disposition on multimedia learning: segment length and learner disposition. Br J Educ Technol. 2015;46(6):1333–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12203.

Howard M, Persky AM. Helpful tips for new users of active learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4):46. https://doi.org/10.5688/ajpe79446.

McLaughlin JE, Gharkholonarehe N, Khanova J, Deyo ZM, Rodgers JE. The impact of blended learning on student performance in a cardiovascular pharmacotherapy course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2):1.

Gharkholonarehe N, McLaughlin, J, Rodgers JE, editors. Impact of a blended-learning approach on student engagement, performance, and satisfaction in a pharmacotherapy course. American Associations of College of Pharmacy; 2013; Chicago, IL.

Blau I, Barak A. How do personality, synchronous media, and discussion topic affect participation? Ed Technol Soc. 2012;15(2):12–24.

Cen L, Ruta D, Powell L, Hirsch B, Ng J. Quantitative approach to collaborative learning: performance prediction, individual assessment, and group composition. Int J Comput-Support Collab Learn. 2016;11(2):187–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-016-9234-6.

Latham A, Hill NS. Preference for anonymous classroom participation: linking student characteristics and reactions to electronic response systems. J Manag Educ. 2014;38(2):192–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562913488109.

Ulbig SG, Notman F. Is class appreciation just a click away?: using student response system technology to enhance shy students introductory American government experience. J Polit Sci Ed. 2012;8(4):352–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2012.729450.

Seidel SB, Tanner KD. “What if students revolt?”—considering student resistance: origins, options, and opportunities for investigation. CBE-Life Sci Ed. 2013;12(4):586–95. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe-13-09-0190.

Lei SA, Kuestermeyer BN, Westmeyer KA. Group composition affecting student interaction and achievement: instructors’ perspectives. J Instr Psychol. 2010;37(4):317.

Post C. Deep-level team composition and innovation: the mediating roles of psychological safety and cooperative learning. Group Organ Manag. 2012;37(5):555–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601112456289.

Millis BJ. Cooperative learning in higher education: across the disciplines, across the academy. 1st ed. New pedagogies and practices for teaching in higher education series. Sterling, Va.: Stylus; 2010.

Fathima MP, Sasikumar N, Roja MP. Memory and learning a study from neurological perspective. i-Manager’s. J Educ Psychol. 2012;5(4):9.

Phan HP. Deep processing strategies and critical thinking: developmental trajectories using latent growth analyses. J Educ Res. 2011;104(4):283–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671003739382.

Maddox GB, Balota DA. Retrieval practice and spacing effects in young and older adults: an examination of the benefits of desirable difficulty. Mem Cogn. 2015;43(5):760–74. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-014-0499-6.

Spruit EN, Band GPH, Hamming JF. Increasing efficiency of surgical training: effects of spacing practice on skill acquisition and retention in laparoscopy training. Surg Endosc. 2015;29(8):2235–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3931-x.

Toppino TC, Gerbier E. About practice: repetition, spacing, and abstraction. SAN DIEGO: ELSEVIER ACADEMIC PRESS INC; 2014. p. 113–89.

Deslauriers L, Schelew E, Wieman C. Improved learning in a large-enrollment physics class. Science. 2011;332(6031):862–4. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1201783.

Haak DC, HilleRisLambers J, Pitre E, Freeman S. Increased structure and active learning reduce the achievement gap in introductory biology. Science. 2011;332(6034):1213–6. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1204820.

Hake RR. Interactive-engagement versus traditional methods: a six-thousand-student survey of mechanics test data for introductory physics courses. Am J Phys. 1998;66(1):64–74. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.18809.

Zoller JK, He JH, Ballew AT, Orr WN, Flynn BC. Novel use of a noninvasive hemodynamic monitor in a personalized, active learning simulation. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41(2):266–9. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00185.2016.

O'Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: a scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.002.

Allaire JL. Assessing critical thinking outcomes of dental hygiene students utilizing virtual patient simulation: a mixed methods study. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(9):1082–92.

Athari Z-S, Sharif S-M, Nasr AR, Nematbakhsh M. Assessing critical thinking in medical sciences students in two sequential semesters: does it improve? J Ed Health Promot. 2013;2:5. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277-9531.106644.

Gorton KL, Hayes J. Challenges of assessing critical thinking and clinical judgment in nurse practitioner students. J Nurs Educ. 2014;53(3):S26–S9. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20140217-02.

Liu OL, Mao LY, Frankel L, Xu J. Assessing critical thinking in higher education: the HEIghten approach and preliminary validity evidence. Assess Eval Higher Ed. 2016;41(5):677–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1168358.

Javed M, Nawaz MA, Qurat-Ul-Ain A. Assessing postgraduate students’ critical thinking ability. J Educ Psychol. 2015;9(2):19.

Ogden WR. Reaching all the students: the feedback lecture. J Instr Psychol. 2003;30(1):22.

Schwartz DL, Bransford JD. A time for telling. Cogn Instr. 1998;16(4):475–522. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532690xci1604_4.

Rawson KA, Dunlosky J. Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: how much is enough? J Exp Psychol Gen. 2011;140(3):283–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023956.

White PJ, Larson I, Styles K, Yuriev E, Evans DR, Short JL, et al. Using active learning strategies to shift student attitudes and behaviours about learning and teaching in a research intensive educational context. Pharm Educ. 2015;15

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Persky, A.M., McLaughlin, J.E. Troubleshooting the Flipped Classroom in Medical Education: Common Challenges and Lessons Learned. Med.Sci.Educ. 28, 235–241 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-017-0505-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40670-017-0505-2