Abstract

Child welfare systems in the Caribbean tend not to take multi-type maltreatment into account when assessing and treating victims of child maltreatment. This study aimed to provide evidence of the prevalence of multi-type maltreatment and patterns of co-occurrence of child abuse and neglect among children and adolescents in community residences across Trinidad. One hundred and two children and adolescents completed the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire which captured five abuse and neglect types: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect. The correlation analyses revealed significant positive relationships among the three types of abuse and a moderate positive correlation between the two types of neglect. T-test results indicated that girls were more likely than boys to experience physical abuse, emotional abuse and sexual abuse, however boys also reported high levels of abuse and neglect. The findings suggest that children are likely to face multiple forms of abuse and neglect that may contribute to its alarming severity and chronicity. Children in community residences are a population of particular interest given that residential care may be considered either a risk or a protective factor depending on the quality of care provided. Recommendations for future research and intervention strategies are proposed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Despite findings that victims of abuse and neglect are highly likely to experience more than one type (Arata et al. 2005; Kim et al. 2017), a multi-type maltreatment approach to child abuse and neglect has been noticeably absent from both research and practice in the Caribbean region. Of the few studies investigating child abuse and neglect (CAN) in the region, most have focused on single types of CAN, primarily physical and sexual abuse. Likewise, child welfare agencies may have been slow to recognize the importance of multi-type maltreatment in their reporting.

While out-of-home care is an important resource for removing children from abusive or neglectful families, the system may have many limitations. Although at-risk children who are removed from the home tend to have a higher quality of life than at-risk children who are not removed (Davidson-Arad et al. 2003), children raised in out-of-home care still do not perform well on several measures of psychosocial and life outcomes (Hodges and Tizard 1989; Viner et al. 2005; Vorria et al. 2003). Research shows however, that the outcomes related to being raised in residential care can be improved or worsened by institutional characteristics such as the provision or lack of individualised care (Merz and McCall 2010; Castle et al. 1999).

To minimize the combined risks associated with being a victim of maltreatment and being raised in residential care, it is necessary to acknowledge the high rate at which child abuse and neglect types co-occur. Evidence of the prevalence of multi-type maltreatment among children in care, will provide an impetus for child welfare agencies in the Caribbean, to implement more thorough assessments to identify and offer personalised treatment to victims of multi-type maltreatment. Such evidence will also prompt researchers in the Caribbean to take a multi-type approach to studying CAN. Finally, an understanding of the types of abuse and neglect which are most likely to co-occur, can provide a better understanding of specific patterns related to maltreatment which can inform broader social interventions and policies for prevention.

The child welfare system in Trinidad and Tobago, though progressing, is still relatively underdeveloped to benefit all abused and neglected children. In a study of child sexual abuse in Trinidad and Tobago, Reddock, & Nickenig, (2014) noted that “the social service structures are not in place to ensure optimal identification of interventions for victims” (p. 258). Several years later, this statement may still be relatively true, as the Children’s Authority of Trinidad and Tobago, the country’s primary child welfare agency, is still at the stage of infancy since it was only established in May 2015. Moreover, similar to the US (Kim et al. 2017), the child welfare services in Trinidad and Tobago tend to focus primarily on a single type of child abuse and neglect in their reports (Children’s Authority of Trinidad & Tobago, 2017). In their Annual Report for 2017, the Children’s Authority detailed the proportions of cases relating to child physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse and neglect, however, no mention is made of the number of multi-type maltreatment cases. Given the high likelihood that various types of abuse and neglect will co-occur, this omission of multi-type maltreatment from all the Authority’s reports is an indication that the Authority may not have placed emphasis on a multi-type approach to dealing with child maltreatment.

Additionally, in the 2017 Annual Report, the Children’s Authority of Trinidad and Tobago indicated that there were 4232 cases of maltreatment reported for the year, however, with regard to assessment, only 125 children (approximately 3% of reported cases) received full medical and psychological assessments. Furthermore, individualised treatment plans were prepared for only 139 children (approximately 3.3% of reported cases). This suggests that, although efforts are being made, a vast majority of the children within public care do not receive thorough assessment nor individualised treatment.

The focus on single-type abuse in the Caribbean region is not limited to the child welfare system but also extends to research as well. Of the few empirical research studies conducted on child abuse and neglect in the Caribbean, the primary focus has been on child sexual abuse (CSA) and child physical abuse (e.g. Jones and Trotman Jemmott 2009; Reid et al. 2014), while even fewer, if any, studies have investigated multi-type maltreatment. Furthermore, most official data on child abuse in the Caribbean come from government agencies and NGOs, which provide the necessary preventive, supportive, and remedial social services to the children and their families (Reid et al. 2014). However, less attention has been given to trend analysis of these rich data sources in relation to evidence informed policy development and strategic planning that would facilitate the care and protection of children. This study attempts to address this chasm by providing insight into such multi-type maltreatment in the Trinidadian setting, to deepen the understanding of such vulnerable children in residential care and to spur improvements in the child welfare system.

Theoretical Framework

Bronfenbrenner’s (1974) ecological systems theory emphasized that a child’s development is influenced by the interaction of their innate characteristics (biological and psychological) with factors within their environment. The theory outlines successive environmental levels at which external factors may influence a child’s development. The first environmental level, the micro-system, encompasses those factors in the child’s immediate environment, which are likely to have the strongest influence on the child’s development, such as family and school characteristics. Both child maltreatment and residential care can be classified as micro-level factors and thus are likely to be strong determinants of a child’s life outcomes.

It is widely accepted that multiple risk factors in a child’s environment are likely to have a cumulative negative effect on the child’s development. Child maltreatment is obviously a detrimental factor for development, and the presence of multi-type maltreatment further compounds this risk, however, residential care may represent either a protective factor or even a risk factor depending on the quality of care provided.

Residential Care

Despite efforts made to expand foster care resources in Trinidad and Tobago, community residences are still one of the primary resources for accommodating children in need of care and protection. In a comparative analysis of the quality of life of children in need of care and protection who were either removed from the home or for whom the decision to remove from the home was not implemented (i.e. remained in the home), Davidson-Arad et al. (2003) found that children who were placed in out-of-home care showed significant improvements in quality of life whereas those who remained in the home showed a decline in quality of life. Despite promising findings from studies in the UK and Canada (Ford et al. 2007; Sigal et al. 2003), children who are raised in community residences show lasting deficits in psychosocial functioning. Even after controlling for adversity in childhood or adulthood, being raised in community residences was significantly associated with poor adult socioeconomic, educational, social, and health outcomes (Viner et al. 2005).

Although it is difficult to disentangle the effects of previous trauma on negative life outcomes from the influence of being raised in out-of-home care, studies have found that institutional factors such as the provision of personalised care can improve outcomes for children raised in community residences (Castle et al. 1999; O’Connor and Rutter 2000; Sigal et al. 2003). Likewise, a hierarchical authoritarian administrative structure can worsen outcomes whereas an egalitarian structure can improve them (Wolff and Fesseha 1998).

It is important to note that protective factors may not always be present in residential care. Residential care interacting with pre-existing traumas can aggravate already maladaptive symptoms (Jones and Sogren 2005). Jones and Sogren (2005) posit that in their study of all of the residential care homes in Trinidad that “across many situations in which the shortage of skilled staff created immense pressure for existing carers. Worryingly however, many of these homes reported increasing demands for residential childcare” (p.29). This does not serve to vilify residential care homes in Trinidad; however, it serves to bring awareness to potential issues. Residential care in itself may not be detrimental to a child’s development and may serve to re-direct a child’s maladaptive development course associated with multiple exposure to trauma. These community residences, therefore, provide an essential service to children who would otherwise be displaced.

Multi-Type Maltreatment

Initially, many studies, made the assumption that the types of maltreatment occur in isolation and investigated only single types of abuse and neglect (Higgins and McCabe 2001). The shift towards investigating multi-type maltreatment has been prompted by strong evidence indicating that the various types of child abuse and neglect are more likely to occur simultaneously, in social, familial and ideological contexts (Kim et al. 2017). In an investigation of the occurrence of multi-type maltreatment, Arata et al. (2005) found that 60% of their participants had experienced two or more forms of maltreatment. Similar findings were observed by Kim et al. (2017) who noted that 65% of participants experienced more than one type of abuse or neglect, and that current official statistics reported by child welfare agencies tend to underestimate and underreport the co-occurrence of multiple types of maltreatment. Their study provided evidence of significant discrepancies in prevalence estimates of multi-type maltreatment from the US’ Child Protective Services, compared to estimates from self-report studies which is indicative of a lack of awareness of the prevalent nature of multi-type maltreatment within child welfare agencies.

The need for a multi-type approach to assessing and treating victims of maltreatment, becomes even more apparent when considering findings that indicate victims of multi-type maltreatment perform worse on measures of psychological, health and social outcomes (Arata et al. 2005; Witt et al. 2016). Furthermore, there is evidence that certain patterns predict worse outcomes than others. Schilling et al. (2015), in using a German sample, found that persons who had experienced multi-type maltreatment had more severe psychological disorders than those who had experienced either single-type or no maltreatment. Patterns of maltreatment also significantly predicted victims’ treatment outcomes whereby victims of multi-type maltreatment with sexual abuse responded worse to treatment than victims of multi-type maltreatment without sexual abuse, and victims of single-type or no maltreatment (Schilling et al. 2015).

In addition to recognizing the occurrence of multi-type maltreatment, it is important that studies investigating CAN also consider age and gender differences in the experience of maltreatment. An understanding of the age and gender of children most at risk for certain types or patterns of maltreatment in the Caribbean context can improve the ability of child welfare agencies to identify and assess cases of maltreatment. Data from the CDC-Kaiser (2016) indicated that girls were more likely to be victims of emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional neglect, whereas boys were more likely to be victims of physical abuse and physical neglect. It has been found that male siblings reported more neglect than female siblings (Hines et al. 2006). With regard to age, it has been found that younger children are more likely to be victimized, and that the highest proportion of victims of child abuse and neglect are children under the age of 4 (Child Maltreatment 2007). An understanding of the factors which places children at a greater risk of multi-type maltreatment in the Caribbean context can improve the ability of child welfare agencies to identify and assess cases of maltreatment. For this reason, the present study will also explore the influence of age and gender on the experience of multi-type maltreatment.

Given that previous research on child abuse and neglect in Trinidad and Tobago, focused only on single-type abuse, the current study aimed to strengthen the evidence base in support of a multi-type maltreatment approach to child abuse and neglect. This study fills a gap in the literature by providing evidence of the prevalence of multi-type maltreatment in the Caribbean context and gave valuable insight into the types of abuse and neglect that are most likely to co-occur. Age and gender differences, as they relate to each of the five types of CAN (physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect), were also investigated.

Hypotheses

It was predicted that: A high proportion of victims of maltreatment will experience more than one type of child maltreatment; significant positive correlations will be observed among the five types of child abuse and neglect; significant age differences in the experience of maltreatment will be observed; and significant gender differences in the experience of maltreatment will be observed.

Method

This study employed a correlational design, using psychometric self-report instruments to assess maltreatment among children living in community residences in Trinidad.

Sample

The study utilised a convenience sample. This method of sampling was dependent on the manager’s (of each community residence) approval and the availability of residents to participate in the study. The manager of each community residence was contacted via an email from the principal investigator. The email outlined key information regarding the nature of the study and requested approval to collect data at the community residence. All community residences for which the request to collect data was approved, were included in the study. The final sample consisted of 102 children from 8 community residences (approximately 22% of homes in the country) from different locations (North, South, East and Central) in Trinidad. Approximately 8–25 participants between the ages of 7 to 18 years were selected from each community residence. As the total number of residents in each community residence (10–30 residents) varied, it was not possible to obtain an equal number of participants from each one. The manager of each community residence identified residents within the age range who were eligible to participate in the study. These participants were invited to participate and were informed that their participation in the study was voluntary.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect data on participants’ characteristics such as age, gender, and ethnicity.

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire

Child Maltreatment was measured using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein and Fink 1997). The CTQ is a 28-item self-report inventory specifically designed to measure five types of child maltreatment: physical, sexual and emotional abuse, as well as physical and emotional neglect. The CTQ asks respondents to recollect childhood events and respond using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Never True to Very Often True. The scale provides ranges for interpreting the severity of each type of CAN. Severity can range from none (or minimal) to low, low to moderate, and moderate to severe.

The internal consistency of the CTQ reported by Bernstein and Fink (1997) was satisfactory to high, with the total scale yielding a Cronbach’s alpha of .95. For the purposes of this study, five of the six subscales were included (physical neglect, emotional neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse and sexual abuse) each subscale consisted of five items, thus a total of 25 items from the CTQ were included in the analyses. The internal consistency reliability coefficients for emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect and for physical neglect were 0.79, 0.81, 0.91, 0.79 and 0.34 respectively. It must be noted that a similar low internal consistency for the physical neglect scale was also reported by Schilling et al. (2016).

Ethical Protocol

Ethical approval was granted by the Campus Ethics Committee of the University of the West Indies. The study adhered to all ethical protocols so as to maintain the welfare and rights of all child participants (UNICEF 2015). All test instruments or protocols, and informed consent were reviewed by the manager of each community residence. With participants being below the age of 18 years, managers at the community residences were responsible for providing the parental/guardian consent.

In keeping with UNICEF’s procedure for ethical standards in research, assent was also sought from the child participants (UNICEF 2015). Children received a consent form with clear guidelines articulating with full disclosure the planned use of the data collected; this was communicated using age-appropriate language and child-friendly methods. In addition, the consent form also provided children with sufficient guidance, that if for any reason they experienced psychological distress, or wanted to discontinue their participation, they were free to withdraw from the study. The informed consent process was completed prior to and separate from the data collection phase to restrict the ability for anyone to identify the results of any single participant. All data were de-identified to protect participants’ confidentiality and anonymity.

Procedure

Participants were given a brief explanation regarding the nature of the research before the questionnaires were administered. The participants were also afforded with the opportunity to ask any questions or express any concerns that they had prior to completing the questionnaire. Depending on literacy levels, the self-report questionnaires were either administered in group settings or individually, and the researchers explained the items that were unclear or any words that were unfamiliar. Before the questionnaires were collected, participants were reminded to ensure that all items were answered. Participants took approximately 20 to 40 minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Frequency analyses were used to determine the prevalence of the various types of CAN. To assess the co-occurrence of various types of CAN, correlation analyses were conducted. T-tests were carried out to determine whether there were gender and age differences in CAN subtypes.

Results

The final sample consisted of 56 males and 46 females (N = 102). The mean age of participants was 13.79 years old with 32% of the sample in the 7–12 age group whereas the remaining 68% were in the 13–18 age group. The three major ethnic groups in Trinidad were included in the study, 39.6% (N = 40) of the sample were Afro-Trinidadian, 21.8 (N = 22) were Indo-Trinidadian, and 38.6% (N = 39) were of mixed heritage.

Prevalence of Child Abuse and Neglect

Only 15% of participants had not experienced physical neglect, 18% had experienced low levels whereas an alarming 67% had experienced moderate to severe levels. With regard to emotional neglect, 25.7% of participants had not experienced this type of maltreatment, whereas 43.1% had experienced moderate to severe levels. The remaining 31.2% experienced low levels of emotional neglect. The rates of physical and emotional abuse were somewhat similar, 29.4% and 30.4% respectively had not been victims of these two forms of abuse. The lowest, although still worrying, prevalence was reported for sexual abuse, with 45% of participants reporting that they had not experienced this type of maltreatment. The severity of each type of maltreatment reported is outlined in Table 1.

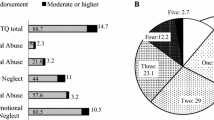

Frequency analyses revealed that only 5 participants (4.9%) had not experienced any of the 5 types of abuse and neglect. As expected, of the 97 participants who had experienced at least one type of child abuse or neglect, only 8 (7.8% of total sample, 8.25% of abuse victims) were victims of just one type of abuse, whereas a vast majority of the total sample (61.8%) were victims of at least 4 types of maltreatment. Data regarding the number of maltreatment types experienced is outlined in Table 2.

Further, analyses revealed that the number of types of maltreatment that participants had experienced, was positively correlated with the severity of the abuse experienced for each of the five abuse types. Thus, those who experienced the most severe levels of abuse were also more likely to have experienced the most types of abuse. The results of the correlation are presented in Table 3.

Correlations among Abuse and Neglect Types

The second hypothesis was tested using a correlation analysis. Most of the abuse and neglect types were significantly associated, while some types were not related, specifically, emotional neglect was not significantly correlated with physical nor sexual abuse. Sexual abuse also was not significantly correlated with physical neglect. The results of the correlation analysis are presented in Table 4.

Age and Gender Differences in Child Maltreatment

T-tests revealed that there were no significant differences in victimization between children (7–12 years) and adolescents (13–18 years) for any of the 5 types of abuse and neglect nor the number of maltreatment types experienced. The results did however reveal significant gender differences in child maltreatment. Specifically, emotional abuse was higher among girls (n = 46, M = 14.85) than among boys (N = 56, M = 9.91), t(83.24) = −4.63, p = .000. Physical abuse was also higher among girls (N = 45, M = 12.82) than for boys (N = 56, M = 10.39), t(99) = −2.22, p = .028. Finally, girls were also more likely to be victims of sexual abuse (N = 45, M = 11.62) than boys (N = 56, M = 7.69), t(74.29) = −3.13, p = .002. There were no significant gender differences in emotional neglect and physical neglect.

Discussion

Although studies on child maltreatment have been moving away from investigating single types of abuse and towards using a multi-type approach, research in Trinidad and Tobago has been slow to follow, with most studies focusing on either sexual or physical abuse. Likewise, the child welfare system often focuses assessment and treatment efforts on the single type of maltreatment that has either been reported or is most evident. As such, this study aimed to strengthen the evidence-base on multi-type maltreatment in the Caribbean and provide an impetus for a multi-type approach to assessment and treatment of children in need of care and protection. Specifically, the study investigated the rate at which victims of abuse experienced more than one type of abuse and the relationships between the five types of abuse and neglect, while also taking age and gender effects into consideration.

As predicted, the results revealed a high prevalence (95.1%) of child abuse and neglect among children in residential care. Most child abuse and neglect victims had also experienced more than one type of maltreatment, in fact, an alarming 61.8% of participants had experienced at least 4 of the 5 types of maltreatment. These findings are consistent with existing literature (Arata et al. 2005; Finkelhor et al. 2011), and provide convincing evidence of the high rate at which the various types of child abuse and neglect co-occur among children in residential care in Trinidad and Tobago.

In their 2017 Annual Report, the Children’s Authority of Trinidad and Tobago indicated that approximately 3% of reported cases received full medical and psychological assessments and, individualised treatment plans were prepared for only approximately 3.3% of reported cases. Although the agency’s protocols for referring children for assessment and for developing treatment plans are unknown, the evidence of the high prevalence of maltreatment, and especially multi-type maltreatment, among children in residential care is indicative of the need for more thorough individualised assessment for most, if not all, of the children in public care.

Additionally, the severity of maltreatment was associated with the number of child abuse and neglect types experienced such that, the more severe the abuse or neglect, the higher the number of abuse and neglect types experienced. Similar to studies in the US (Belsky 1980; Cicchetti and Lynch 1993), these findings fit well within the framework of ecological and transactional perspectives on child maltreatment which assert that maltreatment is likely to occur due to the presence of various risk factors and the lack of protective factors in the child’s environment. It follows logically that the severity and number of abuse types experienced may also be a function of the number of risk factors that are present. Thus, it is likely that the high number of risk factors (and few protective factors) present in a child’s environment may not only increase the likelihood of maltreatment but may also influence the severity of maltreatment, and the likelihood of multi-type maltreatment. Therefore, as children who are exposed to multi-type abuse and neglect are placed in residential care facilities, high quality care standards and conditions must be met for treatment to be effective. However, residential care as it stands in the Trinidadian context may still lack adequate care standards, trained staff, resources and infrastructure (Jones and Sogren 2005). Thus, more should be done by way of improving care standards, assessments, treatments and institutional policies to ensure optimal outcomes for victims of maltreatment raised in residential care. These findings also indicate that severity, and number of maltreatment types experienced are important factors which should be taken into account when assessing and treating children in need of care and protection.

The results of this study revealed correlations among many, but not all, of the five types of maltreatment. There were moderately strong correlations among the three types of abuse (physical, emotional, and sexual) and a moderately strong correlation between the two types of neglect (physical and emotional). Emotional neglect was correlated with only one type of abuse (emotional abuse) and physical neglect was correlated with both physical and emotional abuse, but neither type of neglect was correlated with sexual abuse. These results are consistent with studies that have found that specific patterns of maltreatment exist (Schilling et al. 2015), where certain types of maltreatment are more likely to co-occur. The strongest correlation was observed between physical abuse and emotional abuse, which corroborates the finding that physical maltreatment rarely occurs without psychological maltreatment (Claussen and Crittenden 1991; Hager and Runtz 2012).

T-tests revealed that there were significant differences in maltreatment based on gender. Girls experienced significantly more physical, emotional and sexual abuse than boys. Previous research found that girls experience more emotional and sexual abuse however physical abuse is usually found to be higher among boys (CDC-Kaiser 2016). It is possible that these findings are not consistent with previous research because of culturally held differences in the interpretation and reporting of abuse between males and females. Within the Trinidadian context, gender roles and socialisation are clearly defined and the concept of masculinity is associated with toughness, male honour and dominance (UN Women 2018). It is possible that because of these culturally defined notions of masculinity, boys compared to girls may be less likely to express their emotions as there is evidence to suggest that they often repress memories of abuse in their attempt to cope with painful memories and suppress thoughts and feelings that are distressing (Alaggia and Millington 2008). Research found that non-disclosure of abuse is more adaptive for males than disclosure (O’Leary and Barber 2008). Although the results suggest that girls are more likely to be victims of abuse, it is important to note that boys also reported high levels of abuse and neglect, thus there is need for urgent attention to both boys and girls in residential care.

There was no significant difference in exposure to maltreatment between children and adolescents. While it has been previously reported that younger children are more likely to be maltreated (Child Maltreatment 2007), a study by Finkelhor et al. (2009) found that the patterns of abuse change with age. As such, it is likely that the influence of age on maltreatment is too complex to be reflected in a correlation analysis and may be better investigated using a longitudinal design and time hazard analyses. Further research using Caribbean based samples is required to confirm these results.

These findings present several important implications for the care and protection of children. Firstly, given the findings that 95% of the sample had experienced some form of CAN, and that 87% experienced more than one type, it is imperative that efforts be made to screen all children not only for CAN, but for multi-type maltreatment, regardless of whether maltreatment was reported. The presence of multi-type maltreatment, the pattern of maltreatment, and the severity should inform the development of individual treatment plans that adopt a multi-dimensional approach. While there is evidence of a multidisciplinary approach to assessing and treating with children in residential care in Trinidad and Tobago (Children’s Authority of Trinidad and Tobago Annual Report, 2017), it is unclear whether this approach caters to the specific needs of each child and their vulnerabilities. In adopting a multi-dimensional approach to treatment, there is need for proper follow-up and flow through that includes key stakeholders in the treatment process. Ultimately, public health professionals, clinicians, policy makers, and caregivers should work collaboratively to prevent the complex and often negative outcomes associated with child maltreatment. This calls for the current traditional health models to be revised and to include factors that will explain the risk factors as well as the protective factors for multiple child abuse and neglect types. A revised model that adopts a multi-dimensional approach to treating with child abuse and neglect will be worthwhile to all key stakeholders and contribute to a seamless process that addresses child abuse and neglect in more effective and sensitive ways than the traditional health model in Trinidad.

Limitations

Although this study makes a valuable contribution to the literature on multi-type maltreatment and adds a much-needed Caribbean perspective, there were some limitations which must be highlighted. First, the sensitive nature of child abuse and neglect means that self-report may not provide the most accurate measurement as children may be unwilling to disclose or may have even repressed their past traumatic experiences. However, given the limited availability of verified reports and the social norm of underreporting child maltreatment, self-report measures were the most appropriate assessment tool. Although the physical neglect scale on the Child Trauma Questionnaire lacked internal consistency, a German study also found a lack of internal consistency for the physical neglect scale (Schilling et al. 2016) which may be an indication that this scale is not well suited to measure physical neglect in non-US contexts. There were also some challenges with obtaining a larger sample from this population – there was occasional institutional resistance from community residences which may have influenced the representativeness of the sample of community residences obtained. Finally, there was a lack of interest by some residents to participate in the study and this may have impacted on their willingness to complete the questionnaire.

Conclusion

The current study provided evidence of the high rate at which various types of maltreatment, namely, physical neglect, emotional neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse and sexual abuse, co-occur among children living in community residences in Trinidad. The results showed that the majority of child maltreatment victims had experienced more than one type of abuse. The analyses also revealed a positive correlation between the severity of abuse and the number of abuse and neglect types experienced. Finally, girls were found to be more likely to experience physical abuse, emotional abuse and sexual abuse. These findings indicate the need for future researchers to adopt a multi-type approach when investigating the determinants and effects of child maltreatment in the Caribbean context.

Future research in this area should provide broader prevalence data on multi-type maltreatment from a population-based sample. More studies are needed to clearly identify some of the risk factors of child maltreatment that may be unique to the region and to provide an effective framework geared towards treatment and prevention. Child-centered research principles should be maintained throughout the research processes and beyond as a part of duty of care to child participants.

Additionally, the correlation findings warrant further investigation into the etiology of maltreatment and the environmental conditions which promote various patterns of abuse. Such research will facilitate the design of more effective social policies and interventions for the identification of at-risk families and the prevention of child maltreatment. This type of research is especially necessary within the Caribbean context as there is currently a dearth of literature on child maltreatment. Specifically, current research from European and North American contexts may fail to capture a range of risk factors for maltreatment that is specific to the Caribbean cultural landscape.

Given the findings that most children placed in community residences in Trinidad have experienced several forms of maltreatment, it is imperative that the child welfare system in Trinidad take multi-type maltreatment into account when assessing and treating victims of maltreatment. Such measures will increase the likelihood that residential care will represent a protective factor rather than an additional risk factor for children in need of care and protection. It is important to note however, that protective factors within community residences may not always be present and alternative care arrangements, such as high-quality family-based care, should be considered.

References

Alaggia, R., & Millington, G. (2008). Male child sexual abuse: A phenomenology of betrayal. Clinical Social Work Journal, 36(3), 265–275.

Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Farrill-Swails, L. (2005). Single versus multi-type maltreatment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. https://doi.org/10.1300/J146v11n04_02.

Belsky, J. (1980). Child maltreatment: An ecological integration. American Psychologist, 36(3), 322–323. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.36.3.322.

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1997). Childhood trauma questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, Harcourt, Brace & Company.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1974). Developmental research, public policy, and the ecology of childhood. Child Development, 45(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127743.

Castle, J., Groothues, C., Bredenkamp, D., Beckett, C., O’Connor, T., & Rutter, M. (1999). Effects of qualities of early institutional care on cognitive attainment. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69(4), 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080391.

CDC–Kaiser Permanent ACE (2016). The ACE Study Survey Data [Unpublished Data].

Child Maltreatment. (2007). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, administration on children, youth and families, Children’s bureau. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved from http://www.ncdsv.org/images/HHS-Children%27sBureau_ChildMaltreatment2010.pdf.

Children's Authority of Trinidad and Tobago. (2017). Statistical report on cases October 2016 to September 2017. Port of Spain: Children's Authority of Trinidad and Tobago. Retrieved from http://www.ttchildren.org/images/CA_ANNUAL_REPORT_FINAL_2016-2017_OCTOBER_1.pdf.

Cicchetti, D., & Lynch, M. (1993). Toward an ecological/transactional model of community violence and child maltreatment: Consequences for children’s development. Psychiatry, 56(1), 96–118. Retrieved from 10.1080/00332747.1993.11024624.

Claussen, A. H., & Crittenden, P. M. (1991). Physical and psychological maltreatment: Relations among types of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 15(1–2), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(91)90085-R.

Davidson-Arad, B., Englechin-Segal, D., & Wozner, Y. (2003). Short-term follow-up of children at risk: Comparison of the quality of life of children removed from home and children remaining at home. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(7), 733–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00113-3.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R., Turner, H., & Holt, M. (2009). Pathways to poly-victimization. Child Maltreatment, 14(4), 316–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559509347012.

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Hamby, S., & Ormrod, R. (2011, October). Polyvictimization: Children’s exposure to multiple types of violence, crime and abuse (juvenile justice bulletin). Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice. Retrieved from http://ojs.library.okstate.edu/osu/index.php/FICS/article/view/1649.

Ford, T., Vostanis, P., Meltzer, H., & Goodman, R. (2007). Psychiatric disorder among British children looked after by local authorities: Comparison with children living in private households. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190, 319–325. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025023.

Hager, A. D., & Runtz, M. G. (2012). Physical and psychological maltreatment in childhood and later health problems in women: An exploratory investigation of the roles of perceived stress and coping strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.02.002.

Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(6), 547–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-1789(00)00030-6.

Hines, D. A., Kantor, G. K., & Holt, M. K. (2006). Similarities in siblings’ experiences of neglectful parenting behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(6), 619–637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.11.008.

Hodges, J., & Tizard, B. (1989). Social and family relationships of ex-institutionalinal adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 30(1), 77–97. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/3220/6d646fe2361b6cdb07b952d82a17ed44250b.pdf.

Jones, A., & Sogren, M. (2005). A study of children’s home in Trinidad and Tobago. St. Augustine, Trinidad: Social Work Unit, Department of Behavioural Sciences, The University of the West Indies.

Jones, A.D. & Trotman Jemmott, E. (2009) Child Sexual Abuse in the Eastern Caribbean: Perceptions of, attitudes to, and opinions on child sexual abuse in the Eastern Caribbean. Retrieved from http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/8923/.

Kim, K., Mennen, F. E., & Trickett, P. K. (2017). Patterns and correlates of co-occurrence among multiple types of child maltreatment. Child and Family Social Work, 22(1), 492–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12268.

Merz, E. C., & McCall, R. B. (2010). Behavior problems in children adopted from psychosocially depriving institutions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(4), 459–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-009-9383-4.

O’Connor, T. G., & Rutter, M. (2000). Attachment disorder behavior following early severe deprivation: Extension and longitudinal follow-up. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(6), 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200006000-00008.

O’Leary, P., & Barber, J. (2008). Gender differences in silencing following childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 17(2), 133–143.

Reid, S. D., Reddock, R., & Nickenig, T. (2014). Breaking the silence of child sexual abuse in the Caribbean: A community-based action research intervention model. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(3), 256–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2014.888118.

Schilling, C., Weidner, K., Brähler, E., Glaesmer, H., Häuser, W., & Pöhlmann, K. (2016). Patterns of childhood abuse and neglect in a representative German population sample. PLoS One, 11(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159510.

Schilling, C., Weidner, K., Schellong, J., Joraschky, P., & Pöhlmann, K. (2015). Patterns of childhood abuse and neglect as predictors of treatment outcome in inpatient psychotherapy: A typological approach. Psychopathology, 48, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368121.

Sigal, J. J., Perry, J. C., Rossignol, M., & Ouimet, M. C. (2003). Unwanted infants: Psychological and physical consequences of inadequate orphanage care 50 years later. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 73(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.73.1.3.

UN Women (2018). Gender based violence in Trinidad and Tovago. Office of the Prime Minister, Child and geder affairs. Retrieved from https://www.undp.org/content/dam/unct/caribbean/docs/20181011%20AF%20Trinidad%20and%20Tobago%20Health%20for%20digital.pdf

UNICEF. (2015). Procedure for ethical standards in research evaluation and data collection and analysis (p. 23). New York City: UNICEF. Accessed at: http://www.unicef.org/supply/files/ATTACHMENT_IV-UNICEF_Procedure_for_ethical_standards.PDF.

Viner, R. M., Taylor, B., Risley-Curtiss, C., & Heisler, A. (2005). Adult health and social outcomes of children who have been in public care: Population-based study. Pediatrics, 115(4), 894–899. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2004-1311.

Vorria, P., Papaligoura, Z., Dunn, J., Van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Steele, H., Kontopoulou, A., & Sarafidou, Y. (2003). Early experiences and attachment relationships of Greek infants raised in residential group care. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 44(8), 1208–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00202.

Witt, A., Münzer, A., Ganser, H. G., Fegert, J. M., Goldbeck, L., & Plener, P. L. (2016). Experience by children and adolescents of more than one type of maltreatment: Association of different classes of maltreatment profiles with clinical outcome variables. Child Abuse & Neglect, 57, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHIABU.2016.05.001.

Wolff, P. H., & Fesseha, G. (1998). The orphans of Eritrea: Are orphanages part of the problem or part of the solution? American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(10), 1319–1324. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.10.1319.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of the West Indies Campus Research and Publication Fund (CRP.3. NOV15.6). We would also like to thank the managers of the community residences in Trinidad for their continued support throughout the data collection process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure of Interest

Authors declare that we have no conflicts to report.

Ethical Standards and Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation [institutional and national] and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Descartes, C.H., Maharaj, P.E., Quammie, M. et al. It’s Never One Type: the Co-Occurrence of Child Abuse and Neglect among Children Living in Community Residences in Trinidad. Journ Child Adol Trauma 13, 419–427 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00293-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-019-00293-x