Abstract

This study examines how Time-sync Danmaku Comment (Danmaku) affects college students’ attitudes toward characters in TV series using the Implicit Association Test (IAT) and Event-Related Potentials (ERPs) technique. It is based on the hypothesis related to Opinion Climate. The behavioral data found that Danmaku had limited effects on viewers’ attitudinal tendency and strength. First, regardless of Danmaku attitudes, the participants’ tendency toward positive character did not change significantly, while their attitudes toward negative character became significantly positive. Second, the two groups of participants only showed marginal significance in the differences in the strength of their attitudes toward positive character, which was supported by N2 component. Specifically, the congruent group showed stronger cognitive conflict than the other group. This difference indicates potential asymmetry in viewers’ attitudinal evaluations of positive and negative characters at the physiological level, which means they may have a cognitive processing bias toward positive character. This study argues that the opinion climate has only a limited influence on the formation of attitudes and that attitudinal shifts are not always intrinsic drivers of the transformation from the opinion climate to an individual’s conformity. The opinion climate may contribute more to superficial, unstable, and irrational conformity at the behavioral level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

With the development of the internet, an increasing number of people prefer to watch videos on small screens such as computers and cell phones instead of on the big screen, such as in the theater and on TV. Furthermore, video watching has changed from a shared and collective activity to a relatively closed and individual experience, which has led to the thriving development of the online interactive mode represented by Time-sync Danmaku Comments (hereafter abbreviated as Danmaku). Danmaku is made up of real-time comments that overlay the video and sync with the video timeline. As viewers have a stronger awareness of the subject, Danmaku has become increasingly popular throughout China, as evidenced by its much larger user scale and wider application. As it is known that “the medium is the message,” Danmaku videos (videos with overlaid comments) have changed users’ viewing styles, habits, and even perceptions. It encourages a round of innovation for communication in the online video industry and conveys substantial media discourse and social meaning. Therefore, this study adopts an empirical method to investigate whether Danmaku can influence an individual’s attitudes at the psychological level.

Influence of online comments on consumers’ attitudes

The empowerment of users in the Web 2.0 era has facilitated the development of internet Word of Mouth (IWOM) communication, which refers to informal interpersonal communication about a product, brand, service, or company among noncommercial groups (Robert et al. (2007) and serves as an important reference for consumers in decision-making. The mechanism of online reviews’ influence on consumers’ purchasing intentions and consumption decisions has long been a common interest in academia and industry. Under the Model of Attitude Change-Persuasion by Hovland (Rogers 2002), the issues in the literature are mainly classified as follows: the influence of the characteristics of reviewers (persuaders), the attributes of online reviews (persuasive messages), and the characteristics of consumers (persuasive objects) on consumption decisions. Among them, the attributes of online reviews, which involve the feature of format (Yang and Zhu, 2014), biases (Ludwig et al. 2013; Ma 2014), number, and detailed degree (Wang and Li 2014), have attracted the most attention. Meanwhile, consumer attitude is a core indicator that researchers focus on in studying the transition from online reviews to consumption decisions.

Danmaku is a new form of online commentary. With the popularity of Danmaku in live streaming and online videos, the role of Danmaku in online marketing has also gained increasing attention. Following previous studies on the influence of online reviews, the related empirical studies have focused on the influence of the attributes of Danmaku on consumer attitudes. Existing research generally concluded that Danmaku affects consumer attitudes. For example, it was found that in Danmaku Video Advertising (DVA), Danmaku was positively correlated with users’ attitudes toward the ad and the brand. It is worth noting that this effect is more often shown in ads that appeal to rationality but is not applicable to ads that appeal to emotions (Pei and Guo, 2021). In fact, Danmaku has been widely popular in the field of online video long before it was used in online marketing. Some scholars found through the analysis of Danmaku texts that content interpretation is an important function of Danmaku, among which plots and characters are the major objects that viewers interpret with Danmaku (Wang et al. 2019). This suggests that the extensive interaction between Danmaku and TV series may affect the meaning generated by TV series, causing a shift in viewers’ attitudes. However, only a few empirical studies support this idea. Liu and Li (2016) conducted a survey of Danmaku community groups who watched Return of the Princess Pearl twice and found that Danmaku caused a negative shift in the viewers’ attitudes toward the main characters.

Overall, the existing studies of Danmaku’s effects on attitudes have the following limitations. The first is its limited research areas. Heavily influenced by early research on online commentary, Danmaku-related research has mainly focused on the field of internet marketing, resulting in insufficient attention to other fields (e.g., online film, television, and music). Second, the examination of Danmaku attributes is isolated and sporadic. Existing studies focus either on the validity of Danmaku or on the interaction between Danmaku and videos, thus lacking a more comprehensive and multidimensional analysis. Third, regarding the operationalization of concepts, the operational definitions of attitude in existing studies focus on attitudinal tendencies while ignoring other dimensions of attitude (e.g., attitude strength).

Attitude change: the perspective of opinion climate

Danmaku, by its nature, is a virtual information environment filled with opinions and knowledge, which can be compared to the “Opinion Climate” proposed by German scholar Elisabeth Noel-Neumann. According to The Spiral of Silence: Public Opinion—Our Social Skin (2013), the opinion climate is an “opinion signal” whereby individuals can sense and judge the distribution and possible trends of opinions in their environment. Danmaku can shape the opinion climate because it reveals to viewers the opinions within the group of Danmaku users (specifically, the producers of Danmaku) who have watched the same video. By displaying numerous viewers’ opinions on the screen, Danmaku creates an illusion that a consensus has been reached among the viewers, and that apparent consensus gains legitimacy.

There are two main approaches to studying the influence of opinion climate: the first focuses on cognitive behavior, especially conformity, and the other studies opinion expression, represented by the Spiral of Silence hypothesis. In terms of research content, the latter is an offshoot of the former. Conformity refers to the phenomenon whereby individuals submit to the will of the majority and adopt attitudes or behaviors consistent with them. Research has shown that the individuals can shape and change their attitudes under a certain opinion climate. Sherif’s light-spot experiment and Asch’s (1955) visual line segment experiment supported the existence of conformity at the perceptual level. Subsequently, relevant experiments also verified the existence of an individual’s conformity when people make moral judgments (Cen et al. 1992). With the development of media, Liu (2019) found that conformity continues to exist even in anonymous online situations.

Research on conformity suggests that normative social influence is an important cause of individual conformity, which agrees with the Spiral of Silence hypothesis. According to the hypothesis, the fear of isolation pushes individuals to judge and predict the opinion climate of their environment, whereby they can decide whether to express their opinions publicly or not. Experiments have found that the opinion climate affects not only an individual’s willingness to express his opinion but also the development and change of his opinion (Gerson, 2002). Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1

Viewers’ attitudes toward characters in TV series will shift to the Danmaku opinion climate.

H1.1

Viewers’ attitudes toward positive characters will shift to the Danmaku opinion climate.

H1.2

Viewers’ attitudes toward negative characters will shift to the Danmaku opinion climate.

The opinion climate has multiple levels. In addition to the opinion climate shaped by mass media, individuals can also obtain clues about the majority opinion through reference groups that are close to them, thus forming a model of “dual opinion claims”. Wang et al. (2019) found that the power comparison between dual opinion climates may influence an individual’s attitudes and behaviors. When the reference group’s opinion is the same as that of the mass media, the reference group will strengthen the influence of the mass media; when the reference group’s opinion is opposed to that of the mass media, whether a spiral of silence occurs depends on which opinion climate is more powerful. If the reference group has less influence than the mass media, the reference group’s opinion will be guided by the mass media and thereby reinforce the influence of the mass media, and vice versa. This indicates that there is competition between different levels of opinion climates, and their varying strengths influence how individuals express their opinions.

Referring to the competition framework of dual opinion climate, we distinguish two levels of Danmaku opinion climate and character setting in TV series in an attempt to examine whether the interaction between them will affect viewers’ attitudes toward the characters. Danmaku creates an atmosphere as if a large number of users were watching a movie at the same time, whose virtual presence provides some degree of psychological closeness. Therefore, in a Danmaku video, Danmaku comments are equivalent to the opinion of the reference group. In addition, in terms of fictional artistic narratives such as TV series, producers tend to deliver certain value judgments to viewers via information restrictions or aesthetic effects to achieve specific ideograph purposes (Zhu 2015). From this perspective, there exist two persuasive subjects in Danmaku videos concurrently, i.e., Danmaku, which represents the opinions of the general audience, and the whole narrative, which represents the opinion of TV series producers. In this study, the whole narrative of the TV series is defined as the character setting. If the Danmaku opinion climate is consistent with the character setting, each may strengthen the other and lead to stronger attitudes toward the characters; in contrast, if the two opinions are different, this may lead to a neutral attitude of viewers. Accordingly, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2

The consistency between the Danmaku opinion climate and character setting will enhance viewers’ attitude strength toward the characters in TV series.

H2.1

The consistency between the Danmaku opinion climate and character setting will enhance viewers’ attitude strength toward positive characters.

H2.1

The consistency between the Danmaku opinion climate and character setting will enhance viewers’ attitude strength toward negative characters.

Method

Participants

The participants were 42 college students from a university in Beijing. They were randomly divided into two groups with the same ratio of males to females in each group. One was the congruent group (age: 21.26 ± 1.29, 12 females), who watched a video that contained the Danmaku opinion climate consistent with the character setting (with a positive attitude toward a positive character and a negative attitude toward a negative character). The other was the conflict group (age: 20.48 ± 1.79, 13 females), who watched a video that had a Danmaku opinion climate opposite to the character setting (with a negative attitude toward a positive character and a positive attitude toward a negative character).

None of the participants had watched the Chinese TV series Nothing But Thirty before the experiment, with the exception of two participants who had watched the video clip used in the experiment according to the post-test questionnaire. All participants were right-handed with normal or corrected vision, reported no mental illness or family history, and had not taken alcohol, tobacco, or other psychotropic drugs prior to the experiment. They were required to complete the Chinese version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) before the experiment, none of them showed significant anxiety or depression symptoms, and the differences in BAI and BDI scores between the two groups were not significant. All participants signed an informed consent form before the experiment and were paid for their participation. Forty final valid samples (age: 17–24, M = 20.81 ± 1.59, 25 females and 15 males) are shown in Table 1.

Materials

Danmaku videos

The study selected the TV series Nothing But Thirty as the experimental material. The video clip used in the experiment was intercepted from episode 39, which was 5 min and 44 s long and involved only two characters, namely, Gu Jia (the positive character) and Xu Huanshan (the negative character). The video watched by the congruent group was overlaid with real Danmaku gathered from Tencent Video (as of 12:00 on November 20, 2020). A few interference comments were removed to ensure that all Danmaku participants had a positive attitude toward the positive character and a negative attitude toward the negative character. In contrast, the virtual Danmaku, edited by the researcher and viewed by the conflict group, expressed the opposite attitudes toward the characters as the congruent group. The attitudes of the two groups of Danmaku toward the characters are shown in Table 2. Located in the upper half of the screen, Danmaku consisted of five lines that occupied approximately one-half of the screen. The two groups of participants watched a comparable number of Danmaku words (4211 words in total for the real Danmaku and 4,118 words for the virtual Danmaku) to ensure that the Danmaku moved at a similar speed. The Danmaku video materials are shown in Fig. 1.

IAT

Twenty-six pairs of words were used in the IAT test, including 1 pair of target words, namely, “Gu Jia” and “Xu Huanshan”, and 25 pairs of attribute words (10 pairs in the practice phase and 15 pairs in the test phase), with half of the positive words and half of the negative words. The attribute words were rated by 23 other participants on a 7-point scale (1 for negative and 7 for positive). The validity of positive and negative words was significantly different (t (49) = 25.84, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 7.317). According to the Dictionary of Usage Frequency of Modern Chinese Words: Phonological Part (Liu 1990), the difference in the frequency of attribute words was not significant (t (49) = 0.004, p = 0.997, Cohen’s d = 0.001). The results are shown in Table 3.

Procedure

The study aimed to examine whether Danmaku can influence participants’ attitudes toward characters in TV series (both attitude tendency and attitude strength), with the independent variable being the attitude of Danmaku toward characters and the dependent variable being viewer attitudes toward characters. The study employed a method that combined behavioral and EEG experiments. Before the experiment began, participants signed an informed consent form and completed two pretests about their qualifications. During the formal experiment, participants were required to complete one IAT task before and after watching the Danmaku video, and their EEG data were recorded throughout the experiment. The total task took approximately 45 min. The procedures of this study were approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the School of Journalism and Communication, Beijing Normal University (IRB Number: BNUJ&C20220509001).

The behavioral experiment used the Implicit Association Test (IAT) to measure the viewer’s attitudes toward the characters. Implicit attitudes are potential emotional dispositions and behavioral responses to an object based on individual experiences (Zhang and Zhang 2003). The IAT is an important tool for measuring an individual’s implicit attitudes. Compared with external methods such as questionnaires and self-reports, the IAT has an advantage in that it can prevent participants from reflecting on the association and avoid their self-modification or self-defense (Cui and Zhang 2004) and, thus, shows greater validity.

We improved the IAT procedure on the basis of Cai’s (2003) study on the measurement of implicit self-esteem and added two practice modules. There were 7 steps in total. (1) Present the attribute word and ask the participant to respond immediately (press F for positive words and J for negative words). (2) Present the target word and ask the participant to respond (press F for “Gu Jia” and J for “Xu Huanshan”). (3) Present the target word and the attribute word and ask the participant to respond (press F for the positive attribute word or “Gu Jia” and J for the negative attribute word or “Xu Huanshan”). (4) Repeat step 3. (5) Present the target word and ask the participant to respond in the opposite way as in step 2 (press J for “Gu Jia” and F for “Xu Huanshan”). (6) Present the target word and the attribute word and ask the participant to respond (press F for the positive attribute word or “Xu Huanshan” and J for the negative attribute word or “Gu Jia”). (7) Repeat step 6. Among them, steps 4 and 7 were the formal trial stages, in which the words of different types were presented 60 times randomly. The remaining steps were the practice stage, where the words were presented 20 or 40 times randomly. To avoid possible effects of the presentation order, the sequence of steps and key-press requirements were adjusted to maintain a balance among the participants, except for steps 2 and 5, whose orders were fixed. The specific procedures are shown in Tables 4 and 5.

We used E-Prime 3.0 software to write the IAT program, as shown in Fig. 2. First, a red cross fixation point that lasted 500 ms was presented on the empty screen. Then, the target word or attribute word was randomly displayed in the middle of the screen, and the participant was asked to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. The screen was switched immediately after the participant made a response; otherwise, the word remained on the screen for 2,000 ms before switching automatically to another word. Finally, the screen showed no words and remained empty for 500 ms. The procedure was repeated as follows.

Event-related potentials (ERPs) are brain waves that are superimposed and amplified by multiple identical stimuli, reflecting the neurophysiology changes in the brain during specific cognitive processing (Communication and Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of Renmin University of China 2010). Attitude information processing is a complex mechanism involving perception, attention, cognitive control, conflict processing, etc. ERP technology is an important tool for exploring humans’ internal mechanisms of information processing. A major advantage of ERPs lies in their millisecond temporal resolution and ability to monitor implicit processing in real time, independent of behavioral responses. Therefore, ERP technology is conducive to a more accurate examination of viewers’ processing of Danmaku and an in-depth understanding of the mechanism of how Danmaku influences viewers’ attitudes.

Data recording and analysis

IAT

The analysis of the IAT behavioral data did not include those in the practice phase in the IAT task. Data from participants whose behavioral responses were less than 80% correct (Xu and Zhang, 2009) and whose response time was outside the range of 100–1000 ms were excluded when calculating reaction time. The difference value of the IAT was defined as the difference in reaction time between the negative association tasks and the positive association tasks. A positive D-value represents a positive attitude toward the character; otherwise, it represents a negative attitude toward the character. The absolute IAT D-value indicated the viewer’s attitude strength; the larger the absolute D-value, the stronger the viewer’s attitude toward the character.

EEG

EEG data were recorded using a Cognionics Quick-30 32-Channel Dry Wireless EEG Headset with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. The electrodes were placed according to the international 10–20 standard. DC potentials and EEG signals were obtained from electrodes placed on the forehead with 0–100 Hz bandwidth recording. The average of bilateral mastoids was used as a reference with a low-pass filter (30 Hz) for offline analysis. The participants completed the experiments in a quiet, interference-free laboratory. After data acquisition, EEGLAB 14.1.1 was used to perform an offline analysis for the EEGs that were time-locked when a stimulus was presented during the formal experiment. The length of the epoch was 1200 ms, including a 200 ms prestimulus baseline. EEGs with large drift were manually removed. Artifacts such as blinks, eye movements, and head movements were eliminated using independent component analysis (ICA). After obtaining clean data, the data from the nine electrode points F3, Fz, F4, C3, Cz, C4, P3, Pz, and P4 were selected for offline analysis. The EEG data evoked in the four tasks, i.e., “positive character-positive association”, “positive character-negative association”, “negative character-positive association” and “negative character-negative association”, were averaged separately, with at least 30 valid trials.

Results

Behavioral data (IAT)

The IAT data of all participants are shown in Table 6. Separate independent sample t tests of the IAT pretest scores of the two groups of participants revealed that the initial attitudes of the two groups toward the positive character (t (39) = 0.085, p = 0.933, Cohen’s d = 0.029) and toward the negative character (t = − 1.536, p = 0.133, Cohen’s d = 0.500) were not significantly different.

Attitudinal tendency

Paragraph use this for the first paragraph in a section, or to continue after an extract.

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on group (congruent group vs. conflict group) × test time point (pretest vs. post-test), with group as a between-group factor and test time point as a within-group factor. The results are as follows:

Positive character The main effect of group was not significant (F (1, 40) = 0.400, p = 0.531, η2p = 0.010); the main effect of test time point was not significant (F (1, 40) = 0.373, p = 0.545, η2p = 0.010); and the interaction between the two was not significant (F (1, 40) = 0.256, p = 0.616, η2p = 0.007).

Negative character The main effect of group was not significant (F (1,40) = 0.075, p = 0.786, η2p = 0.002); the main effect of test time point was significant (F (1, 40) = 4.167, p = 0.048, η2p = 0.099); and the participants’ IAT post-test scores for the negative character (M = 13.043) were significantly higher than pretest scores (M = − 10.115), indicating that after viewing the experimental material, the participants in both groups shifted their attitudes toward the negative character in a positive direction. The interaction between the group and test was not significant (F (1, 40) = 0.583, p = 0.450, η2p = 0.015).

In summary, H1 was partially supported, and the Danmaku effect on viewers’ attitudinal tendency was limited. Specifically, after receiving the experimental stimuli, there was no significant change in the attitudes of participants in either group toward the positive character, and therefore H1.1 was not supported; the participants’ attitudes in both groups toward the negative character significantly shifted in the positive direction. In other words, only the attitudes of the conflict group toward the negative character shifted following the Danmaku opinion climate; thus, H1.2 was not fully supported.

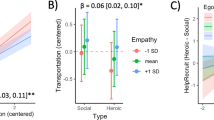

Attitude strength

An inter-group independent sample t test analysis of the absolute values of the post-test IAT scores for the two characters revealed that the difference in attitude strength between the two groups toward the positive character was marginally significant (t = 1.866, p = 0.070, Cohen’s d = 0.587); and there was no significant difference in attitude strength toward the negative character (t = − 0.655, p = 0.516, Cohen’s d = 0.210). The above data results did not support the two sub-hypotheses of H2, and the consistency between the Danmaku opinion climate and the character setting did not significantly influence the strength of viewers’ attitudes toward the characters.

Electroencephalogram results (ERPs)

The EEG data from three participants were lost due to operational errors, and the data from three participants with excessive artifacts were also eliminated, leaving 34 participants’ EEG data for final analysis.

The IAT test requires the target words to be semantically associated with negative or positive attributes, leading to the result that the target words have emotional color. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the influence of early emotional effects on cognitive processing with P1 component. At the same time, the IAT test focuses on cognitive conflict between participants’ performance on compatible and incompatible tasks. A study (Banfield et al. 2006) proposed that participants’ implicit attitude caused the difference in frontal stimulation at the early stage of seeing target words and attribute words. Therefore, the N2 component basically reflects the implicit attitude of the participants.

Based on previous research literature combined with the topographic results of this study, Pz electrodes were selected to measure the P1 component (time window: 130–220 ms for the positive character, 120–230 ms for the negative character), Fz electrodes were selected to measure the N2 component (time window: 230–350 ms for the positive character, 250–350 ms for the negative character), and then the two characters’ differences on ERPs were compared separately under the two association tasks. The specific mean wave amplitudes are shown in Table 7, the waveform plots of ERPs are shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5, and 6, and the topographic plot of ERPs is shown in Fig. 7.

All components were measured by the mean wave amplitude method, and a repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted for group (congruent group vs. conflict group) × association mode (positive association vs. negative association), with group as a between-group factor and association mode as a within-group factor. The statistics were corrected using the Greenhouse–Geisser method.

P1 component

Positive Character The main effect of group was not significant (F (1,34) = 0.027, p = 0.871, η2p = 0.001); and the main effect of association mode was not significant (F (1, 34) = 0.098, p = 0.756, η2p = 0.003). Neither was the interaction between group and association mode significant (F (1, 34) = 0.516, p = 0.478, η2p = 0.016).

Negative Character The main effect of group was not significant (F (1,34) = 1.646, p = 0.209, η2p = 0.049); and the main effect of association mode was not significant (F (1, 34) = 0.562, p = 0.459, η2p = 0.017). Neither was the interaction between group and association mode significant (F (1, 34) = 1.124, p = 0.297, η2p = 0.034).

N2 component

Positive Character The main effect of group was not significant (F (1,34) = 0.181, p = 0.673, η2p = 0.006); the main effect of association mode was significant (F (1, 34) = 6.980, p = 0.013, η2p = 0.179); and the N2 wave amplitude elicited by negative association (incompatible condition) was significantly larger (M = − 3.699) than that elicited by positive association (compatible condition). The interaction of group and association mode was significant (F (1, 34) = 7.122, p = 0.012, η2p = 0.182). Further simple effects analysis using Bonfferoni’s method revealed that in the congruent group, the N2 wave amplitude elicited by negative association (incompatible condition) was significantly greater than that elicited by positive association (compatible condition) (p = 0.001), while in the conflict group, there was no significant difference in the N2 wave amplitude elicited by the two association modes (p = 0.985).

Negative Character. The main effect of group was not significant (F (1,34) = 0.055, p = 0.817, η2p = 0.002); the main effect of association mode was significant (F (1, 34) = 13.437, p = 0.001, η2p = 0.296); and the N2 wave amplitude elicited by positive association (incompatible condition) was significantly larger (M = − 2.897) than that elicited by negative association (compatible condition) (M = − 0.791). The interaction between group and association mode was not significant (F (1, 34) = 2.293, p = 0.140, η2p = 0.067).

Discussion

General discussion

This study investigates the influence of Danmaku on viewers’ attitudes, attempting to answer two research questions: first, can Danmaku attitudes (positive vs. negative) influence viewers’ attitude tendency toward characters; and second, can the consistency between Danmaku attitudes and the character setting (congruent vs. conflict attitudes) affect the strength of viewers’ attitudes toward the characters? The behavioral results found that the direction of viewers’ attitudes toward the characters was less influenced by Danmaku, and only the conflict group’s attitude toward the negative characters shifted following the Danmaku opinion climate, which partially supported H1. The difference in attitude strength between the two groups toward positive characters was marginally significant, and thus H2 was not supported. However, the data still showed the trend that the consistency between the Danmaku opinion climate and the character setting of the TV series may enhance viewers’ attitude strength toward positive characters.

The EEG results showed that the wave amplitude of N2 under the incompatible condition was significantly larger than that under the compatible condition for both positive and negative characters. Previous studies have found that the frontal N2 component tends to be closely related to cognitive control and cognitive conflict, and the larger the wave amplitude of N2, the greater the cognitive control and cognitive conflict. In this study, for the positive character, the wave amplitude of the N2 evoked by the incompatible condition was significantly larger than that evoked by the compatible condition in the congruent group. This suggests that in the congruent group, participants differed in their cognitive processing of the different association tasks and that the incompatible task resulted in stronger cognitive conflict than the compatible task. However, this difference in the wave amplitude of the N2 evoked by the two association modes disappeared in the conflict group. This suggests that participants in this group were unable to distinguish between compatible and incompatible conditions by the N2 and that the cognitive conflict was dissipated. The comparison between the two groups indicated that congruent Danmaku reinforced the viewers’ positive attitudes toward the positive character, while incongruent Danmaku had the opposite effect, causing a certain degree of confusion in viewers’ attitudes and making them fail to distinguish a clear tendency. This is basically consistent with the trend presented by the behavioral results: the consistency between Danmaku and character setting will strengthen viewers’ attitudinal tendency toward positive characters and make their positive attitudes clearer, while the conflict between the two will, to some extent, blur viewers’ attitudinal tendency and make their attitudes waver. In the case of the negative characters, the EEG data did not show inter-group differences, and the wave amplitude of the N2 evoked in the incompatible condition was significantly larger than that evoked in the compatible condition for both groups, i.e., the positive association triggered stronger cognitive conflict than the negative association. This indicates that the Danmaku comments did not influence the participants’ cognitive processing of the different association modes toward the negative characters. In particular, the in-congruent Danmaku failed to interfere with viewers’ negative attitudes toward the negative characters.

The above comparison reveals that in the early stages of cognitive processing, viewers’ attitudes toward positive characters are significantly influenced by Danmaku, while their attitudes toward negative characters are less influenced. This asymmetry implies that viewers’ attitudinal evaluations of positive and negative characters may be unequal at the physiological level, which may be relevant to positive emotional bias, i.e., the human brain shows greater sensitivity and processing bias to positive emotional stimuli under certain conditions. Studies have found that people have varying degrees of positive bias in positive, negative, and neutral self-reported expressions (Cornelia et al. 2018). This positive linguistic bias is also supported by evidence from written corpora as well as natural speech samples (Augustine et al. 2011). It has been shown that participants recall positive words at a higher rate than neutral or negative words (Verno et al. 2007). On a physiological level, it was found that pleasant words evoked higher N400 and LPP than unpleasant words during an uninstructed word reading task, suggesting a natural bias toward pleasant content during cognitive processing (Herbert et al. 2008). Similar to the aforementioned studies, the stimuli used in this study were words with low arousal characteristics. In the study, participants may have had a cognitive processing bias toward positive characters. They were more perceptive of different comments on positive characters and thus had deeper cognitive processing, leading to stronger brain responses. This was supported by significant differences in the level of N2 in the ERPs data between the two groups. In contrast, the cognitive processing resources that participants devoted to the negative characters were scarcer, and no difference was found in the N2 component between the two groups of participants who viewed different Danmaku.

In addition, although both groups triggered stronger cognitive conflict toward the negative character in positive association tasks than in negative association tasks, their attitudes toward the negative character were significantly skewed in a positive direction, as shown by the behavioral data. This suggests that there is an inconsistency between participants’ cognitive activities and attitudinal responses regarding the negative character. Additionally, the P1 component revealed that the change in audience attitudes was unrelated to early attention allocation. Consequently, there are several possible explanations. One explanation is that Danmaku still affects the participants’ attitudinal shift, which only occurs in the post-cognitive conflict stage, such as emotional or behavioral responses; thus, the participants form a certain mechanism of attitudinal tendency in the late stage of information processing. This mechanism is independent of the cognitive evaluation and only related to emotional or behavioral responses. Another explanation is that the mere exposure effect has a positive effect on attitude evaluation. Heingartner and Hall (1974) found a significant positive correlation between exposure frequency and liking for both visual and auditory stimuli. It has been shown that the Mere Exposure Effect also acts on an individual’s ethical tolerance for a particular business decision (Weeks et al. 2005). In this study, the participants watched a Danmaku video containing both visual and auditory stimuli, and the video clip addressed ethical issues related to marriage. Thus, this research shared similarities with previous studies. The behavioral results showed that both groups experienced a significant positive shift in their attitudes toward the negative characters. This suggests that regardless of Danmaku attitudes toward the negative character, the act of watching the video may produce a Mere Exposure Effect on the participants, resulting in more favorable opinions of the negative character.

In conclusion, the formation of individual opinion is less influenced by the opinion climate. Prior research has shown that anonymity affects conformity behavior: individuals show less conformity when answering privately and greater conformity when answering publicly or when individuals believe that the answer may be visible to most people (Deutsch and Gerard 1955; Xie 2003; Liu 2019). The most popular explanation for this is that anonymity reduces the effect of group pressure on individuals. In regard to Danmaku videos, although individuals obtain information from the group, they do not need to express their own opinions to other group members and are, thus, less constrained by group pressure. Kelman (1958) found that even if individuals adopt consistent behaviors in public, their underlying processing may be different. Thus, he distinguished three levels of attitude change: compliance, identification, and internalization. Different types of attitude change predict different motivational mechanisms and may lead to different behaviors. This suggests that the influence of opinion climate on attitude formation is limited and that attitude change is not always an intrinsic driver in the transformation from opinion climate to conformity. For this reason, the opinion climate may contribute more to conformity behavior that is superficial, unstable and irrational. These findings remind us that although the development of internet technology and big data makes it possible for more targeted and controllable monitoring of public opinion, the public opinion referred to through behavioral data may be a constructed social reality that does not reliably reflect the real psychological tendency of the public. Therefore, more emphasis should be placed on the physiological aspect of public opinion analysis. Moreover, in addition to evaluating the opinion climate’s effect on different issues, further research is required to examine its impact on different participants under the same issue.

This study is innovative in following aspects. First, in terms of the research area, this study focuses on the influence of Danmaku in the popular field of online television. It starts by investigating the viewers’ attitudes toward the characters and investigates how Danmaku affects college students’ attitudes toward the characters. Second, this study uses the behavioral experiment paradigm in the field of psychology combined with the methods of cognitive neuroscience to measure attitudes. The investigation of the instantaneous effect with the help of ERP method is an important supplement to the long-established research on the communication effect based on behavioral experiments, which focuses on the medium or long-term effect (Yu et al. 2011), and is conducive to more in-depth analysis of each link of the communication phenomenon and the correlation between various variables. At the same time, the emphasis on instantaneous effect is also in line with the current situation of rapid change of media information and quantity overload. Third, by drawing on previous studies, this study examines how the attitudinal tendency of Danmaku and the interaction between Danmaku and video can influence viewers’ attitudes in different ways. Furthermore, this study operationalizes viewers’ attitudes in two dimensions, i.e., attitudinal tendency (positive vs. negative) and attitude strength, to conduct a more detailed and comprehensive investigation of the influence on attitude.

Limitations and future directions

This study also has several limitations. First, since the viewers of TV series are from various backgrounds, college students as a sample are not representative, so this study cannot explain the influence of Danmaku on other types of audiences. Second, as TV series cover multiple topics and Danmaku is widely used in many contexts, it is unclear whether the findings of this study are applicable to other types of TV series or other Danmaku scenarios. Moreover, this study only focuses on the instantaneous effect of a single Danmaku video on viewers’ attitudes while ignoring the cumulative and long-term effects of multiple Danmaku videos. Therefore, further research in the future would benefit from addressing these issues.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, DHQ, upon reasonable request.

References

Asch. 1955. Opinions and social pressure. Scientific American 193 (5): 31–35. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1155-31.

Augustine, Adam, Matthias Mehl, and Randy Larsen. 2011. A positivity bias in written and spoken english and its moderation by personality and gender. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2 (5): 508–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550611399154.

Banfield, Jane, Arie van der Lugt, and Thomas Münte. 2006. Juicy fruit and creepy crawlies: an electrophysiological study of the implicit Go/NoGo association task. NeuroImage (Orlando Fla) 31 (4): 1841–1849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.017.

Cai, Hua-Jian. 2003. 内隐自尊效应及内隐自尊与外显自尊的关系[The Effect of Implicit Self-esteem and the relationship of Explicit Self-esteem and implicit Self-esteem]. Acta Psychologica Sinica 06: 796–801.

Cen, Guozhen, Jinghai Liu, and Yimin Sheng. 1992. 8–12 岁儿童道德判断的从众现象[On the conformity of Moral judgement among children aged from 8 to 12]. Acta Psychologica Sinica 03: 267–275.

Communication and Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of Renmin University of China. 2010. 媒介即信息:一项基于MMN的实证研究——关于纸质报纸和电纸书报纸的脑认知机制比较研究[Medium is message: an empirical analysis based on MMN A comparative study of cognitive mechanisms on newspapers and electronic books]. Chinese Journal of Journalism Communication 11: 33–38.

Deutsch, Morton, and Harold Gerard. 1955. A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 51 (3): 629–636. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046408.

East, Robert, Kathy Hammond, and Malcolm Wright. 2007. The relative incidence of positive and negative word of mouth: a multi-category study. International Journal of Research in Marketing 24 (2): 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2006.12.004.

Gerson, Moreno-Riaño. 2002. Experimental implications for the spiral of silence. The Social Science Journal (Fort Collins) 39 (1): 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0362-3319(01)00174-4.

Guoming, Yu., Ou. Ya, and Li. Biao. 2011. 瞬间效果:传播效果研究的新课题——基于认知神经科学的范式创新[Instantaneous effects: a new topic in the study of communication effects: paradigm innovation based on cognitive neuroscience]. Modern Communication. Journal of Communication University of China 03: 28–35.

Heingartner, Alex, and Joan Hall. 1974. Affective consequences in adults and children of repeated exposure to auditory stimuli. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 29 (6): 719–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036121.

Herbert, Cornelia, Eileen Bendig, and Roberto Rojas. 2018. My sadness - our happiness: writing about positive, negative, and neutral autobiographical life events reveals linguistic markers of self-positivity and individual well-being. Frontiers in Psychology 9: 2522–2522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02522.

Herbert, Cornelia, Markus Junghofer, and Johanna Kissler. 2008. Event related potentials to emotional adjectives during reading. Psychophysiology 45 (3): 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00638.x.

Kelman, Herbert. 1958. Compliance, identification, and internalization: three processes of attitude change. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 2 (1): 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/002200275800200106.

Li-Juan, Cui, and Zhang Gao-Chan. 2004. 内隐联结测验(IAT)研究回顾与展望[The studies of the Implicit Association Test(IAT)]. Journal of Psychological Science 01: 161–164.

Noelle-Neumann, Elisabeth. 2013. The spiral of silence: public opinion - our social skin. Beijing: Peking University Press.

Rogers, E. M. 2002. A history of communication study: A biographical approach (X. R. Yin, Trans). Shanghai Translation Publishing House (Original Work Published 1997).

Ruyter, Stephan, Mike Friedman, Elisabeth Brüggen, Martin Wetzels, and Gerard Pfann. 2013. More than words: the influence of affective content and linguistic style matches in Online Reviews on Conversion Rates. Journal of Marketing 77 (1): 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.11.0560.

Verno, Karri Bonner, Stanley Cohen, and Julie Hicks Patrick. 2007. Spirituality and cognition: does spirituality influence what we attend to and remember? Journal of Adult Development 14: 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-007-9020-9.

Wang, Cheng-Jun. 2019. 找回失落的参考群体:对沉默的螺旋理论的边界条件的考察[Bringing back the reference group: the boundary condition of the spiral of silence theory]. Journalism Research 04: 116–117.

Wang, Jun. 2014. 网络评论信息对消费者购买态度的影响研究[Research on the Impact of network review information on customers’ purchasing attitude]. Information Studies: Theory Application 09: 121–124.

Wang, R., R.Y. Liu, L.B. Jiao, and J.Y. Xu. 2019. 走向大众化的弹幕:媒介功能及其实现方式[Toward a popular Danmaku: media functions and their realization]. Shanghai Journalism Review 05: 44–54.

Weeks, William, Justin Longenecker, Joseph McKinney, et al. 2005. The role of mere exposure effect on ethical tolerance: a two-study approach. Journal of Business Ethics 58: 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-004-2167-4.

Xie, X.Z. 2003. 沉默的螺旋假说在互联网环境下的实证研究[An empirical study of the spiral of silence hypothesis in the internet environment] Modern Communication. Journal of Communication University of China 06: 17–22.

Xu-Ying, Liu. 2019. 互联网时代下阿希从众实验在中国的探索性实证研究[Asch conformity experiments in the internet era: an exploratory empirical research in China]. Modern Communication. Journal of Communication University of China 09: 13–18.

Xu, Ying, and Zhang Qing-Lin. 2009. 吸烟者内隐态度的ERP研究[An ERP Study of Implicit attitude of smokers]. Psychological Exploration 02: 33–37.

Yang, Ying, and Zhu Yi. 2014. 无图无真相?图片和文字网络评论对服务产品消费者态度的影响[No picture, no truth? the affect of pictorial and verbal service online reviews on consumer attitudes]. Psychological Exploration 01: 83–89.

Yanli, Ma. 2014. 冲突的在线评论对消费态度的影响[The influence of conflict of online reviews on consumer attitudes]. On Economic Problems 03: 37–40.

Yanli Pei, and Ting Guo. 2021. Can Danmaku video advertising lead to better advertising effects? Wanfangdata. https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/conference/10208322.

Yuan, Liu, and Qiu-LI. Li. 2016. 网络荧屏互动对受众态度的影响——以弹幕互动对《还珠格格》角色形象的影响为例[The influence of online screen interaction on audience’s attitude: a case study of the influence of Danmaku interaction on the character image in return of the princess pearl]. Youth Journalist 27: 34–35.

Yutang, Lin. 1990. 现代汉语常用词词频词典:音序部分[Dictionary of usage frequency of modern Chinese words: phonological part]. Beijing: China Astronautic Publishing.

Zhang, Lin, and Xiang-Kui. Zhang. 2003. 态度研究的新进展:双重态度模型[Recent progress of research on attitudes: a model of dual attitudes]. Advances in Psychological Science 02: 171–176.

Zhu, Hong. 2015. 视点与聚焦:影视叙事的信息传播及审美动机[Point-of-view and the focus: Information dissemination and aesthetic motive of film; TV narrative]. Contemporary Cinema 09: 59–63.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Project of Beijing Social Science Fund “Research on Cognition and Expression characteristics and Governance of Online Public Opinion in Beijing” under Grant number 21XCA004. We thank all the participants for their help during this research. Besides, any comments and suggestions are really appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethical approval

The experiments comply with the current laws of the country in which they were performed.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanqing, D., Lichao, X. & Huali, C. How Danmaku influences college students’ attitudes toward characters in TV series: evidence from ERPs. Int. Commun. Chin. Cult 11, 133–153 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40636-024-00279-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40636-024-00279-x