Abstract

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a major public health concern with significant associated economic costs. Although the disease affects all ethnic groups, about 90% of individuals living with sickle cell disease in the USA are Black/African American. The purpose of this study was to assess the health care discrimination experiences of adults living with SCD and the quality of the relationship with their health care providers. We conducted six focus groups from October 2018 to March 2019 with individuals receiving care at a specialized adult sickle cell program outpatient clinic at a private, nonprofit tertiary medical center and teaching hospital in the northeastern USA. The sample of 18 participants consisted of groups divided by gender and current use, past use, or never having taken hydroxyurea. Ten (56%) participants were males; most were Black/African American (83%) and had an average age of 39.4 years. This study reports a qualitative, thematic analysis of two of 14 areas assessed by a larger study: experiences of discrimination and relationships with providers. Participants described experiences of bias related to their diagnosis of SCD as well as their race, and often felt stereotyped as “drug-seeking.” They also identified lack of understanding about SCD and poor communication as problematic and leading to delays in care. Finally, participants provided recommendations on how to address issues of discrimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a serious, chronic, genetic disease that has been estimated to affect approximately 100,000 people in the USA [1], although this number may be an underestimate [2]. SCD is characterized by an array of clinical manifestations including recurrent episodes of severe pain, acute chest syndrome, chronic hemolytic anemia, increased susceptibility to infections, stroke, and multiple organ damage. Untreated, SCD leads to significant morbidity and early mortality [3], and studies suggest that over half of patients may discontinue treatment within a year [4] and discontinuation of treatment has been associated with decreased survival [5]. While newer gene therapy treatments are emerging which could potentially cure hemoglobinopathies such as SCD [6], current management of SCD commonly requires pharmacological pain treatment, frequent hospitalizations, and use of the emergency department [7]. Individuals with SCD frequently report poor quality interactions with health care providers when they seek treatment for pain, and are sometimes labeled “drug seeking” [8, 9]. This often leads to health-related stigma and persists despite research showing opiate overdose is less common in individuals with SCD compared with other chronic pain syndromes [10].

Prior studies have shown that health-related stigma experienced by patients living with SCD contributes to a sense of distrust with health care providers [9, 11, 12]. In addition, poor patient-provider communication among adults living with SCD is associated with lower trust toward the medical system [13]. Adult patients with SCD and caregivers of children and adolescents with SCD report that these health-related stigma and distrust affect their medical decision-making, such as delaying care for fear of being labeled or discriminated against and prematurely self-discharging from the hospital [12, 14]. Health-related stigma and distrust are also negatively associated with stress and pain in adults with SCD [15]. While distrust of health care providers in Black Americans has been associated with lower screening rates and/or worse outcomes for diseases such as colorectal cancer [16] and prostate cancer [17], research on associations between distrust and outcomes in SCD is lacking.

Perceived discrimination due to race and/or disease may further increase the level of stigma and distrust experienced by patients and families affected by SCD, which may worsen quality of life, particularly as patients grow older [18]. Notably, perceptions of discrimination or that race influences interactions are significantly higher in patients than in medical staff [19]. Perceived discrimination is associated with multiple negative psychological and physical health outcomes [20, 21]. In adults living with SCD, perceptions of discriminatory experiences from health care providers are associated with nonadherence to physician recommendation [22] and self-reported pain [23]. The purpose of the current paper is to further evaluate the role of patient trust, patient-provider communication, and discrimination on treatment adherence and health care quality in adults living with SCD. We also provide patient-identified recommendations to address perceived discrimination.

Materials and Methods

These data were collected as part of an assessment of the treatment experiences of adults living with SCD and receiving services through a hospital-based outpatient clinic in a small city in the northeast between October 2018 and February 2019. The data presented in this paper were obtained through focus groups conducted by a team of doctoral-trained psychologists with no affiliation to the clinic. Funding for this assessment was provided by an academic department of psychiatry as part of a project to develop behavioral interventions to improve treatment adherence. The data collection protocols were developed with input from the leadership at the clinic, while the data collection, analysis, and final reporting were conducted independently by the consultants. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (protocol 2000023730).

The focus group protocol included questions about participants’ treatment history for SCD; other treatments they are using to manage symptoms related to SCD; their opinion of the safety of hydroxyurea; whether they feel that they had the information they needed to determine whether hydroxyurea should be part of their treatment plan; perceptions of barriers to hydroxyurea and other medication adherence; perceptions of their relationship with their health care provider; experience receiving care for sickle cell disease at the hospital-based clinic; and perceptions of and experiences of discrimination and stigma toward individuals with sickle cell disease or toward them personally by the health care system or health care providers.

This manuscript includes a subset of the data gathered as part of the larger study that focuses on participant perceptions of and experiences of discrimination and stigma as they received care for SCD. The focus group facilitators defined discrimination during the groups as the health care system or health care provider treating them differently and worse than someone else for certain reasons. Participants were asked if they had ever felt discriminated against by the health care system due to their diagnosis of sickle cell disease. Additionally, they were asked if they had ever felt stigmatized, discriminated against, or labeled, or treated like a stereotype by their SCD health care team.

Focus groups were facilitated by authors C.C. and J.K., who have extensive experience in qualitative research including the development of protocols, facilitation, and data analysis. Author C.N. took detailed notes of each group. The focus groups were audio recorded and a verbatim transcript was produced; the notes were used to fill in any voids in the transcriptions and to confirm that each statement was accurately assigned to respondents. The institutional Human Research Protection Program provided oversight of the study with regard to human subjects protections, and participants gave verbal consent for participation in the focus group. No ethical concerns arose during the study. Focus groups were 2 h in length, and participants were provided with a meal and received a $25 stipend for their participation.

Participants

Current patients of the hospital-based outpatient clinic ages 18 and older were eligible to participate in the focus groups. Participants were recruited by clinic staff to one of six groups divided by gender. Prior to participating in the focus groups, participants were informed that the purpose of the focus group was to gather their perceptions of the care provided to individuals with SCD and that their responses would only be shared anonymously and in aggregate. After participants gave verbal consent, they were asked to complete a de-identified written questionnaire to gather participant-specific demographic and descriptive information including gender, age, race, ethnicity, educational level, employment status, household income, and current housing/living situation. In addition, participants provided information about their SCD history and experience, co-occurring health conditions, health insurance status, and current medications taken.

Data Analysis

Multiple strategies were utilized to increase creditability, transferability, dependability, and confirmability of the findings [24]. First, all themes included in the summary were endorsed by three or more informants. Second, respondents recounted their experience receiving treatment at the hospital-based clinic and the treatment they received from other providers both in and outside of this facility. Third, two senior members of the evaluation team independently coded each of the transcripts and then met to review their codes and discuss any discrepancies. Finally, the evaluation consultants have no relationship with the hospital-based clinic. Data was entered into a spreadsheet to allow for sorting by code and analyzed by the doctoral-level psychologists. Grounded theory methods [25] were used to identify themes related to participant perceptions of and experiences of discrimination and stigma experienced as they received care for SCD. This analytic strategy was chosen as its central aim is theory building and therefore appropriate for an exploratory study [26,27,28].

Results

There was a total of 18 participants across the six focus groups including 10 males and 8 females. Most of the participants self-identified as Black/African American (83%), followed by mixed race (11%) and other racial background (6%). One participant (6%) self-identified as Latino/Hispanic. Participants had a mean age of 39.4 years, with a range of 20 to 68 years of age.

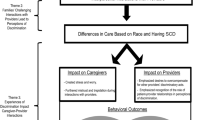

The results provided below represent the qualitative analysis of two domains assessed in this study: experience of discrimination and relationship with providers. The analyses yielded four sub-themes related to participants’ experiences of discrimination: pain and pain management, quality of care, perceived reasons for discrimination and bias experienced, and recommendations to address discrimination. There were four sub-themes regarding patients’ relationship with their providers: communication, sense of trust, power dynamics, and overall satisfaction. Within each sub-theme, examples are provided to demonstrate participants’ experiences with the health care system and their providers. A summary can be found in Table 1.

Experiences of Discrimination

Experiences of and perceptions of discrimination, bias, and stereotyping by the health care system or by their providers emerged in all six of the focus groups conducted. Seventeen of the 18 focus group participants reported direct experiences with discrimination, bias, or stereotyping. Below we describe the discrimination sub-themes that emerged, which include discrimination in care, pain management and quality of care, and perceptions of the cause of discrimination and recommendations to address it.

Pain and Pain Management

A recurring subtheme that emerged from the data related to experiences of pain and pain management. Participants felt that providers, including physicians, advanced practice providers, and nursing staff, failed to understand and to respect that the pain they experience is real, excruciating, and debilitating, which is the reason they present to the emergency department or are admitted to the hospital. A frequently cited participant experience in the emergency department was that rather than believe patient self-reported pain, patients are often made to wait for laboratory results from blood work to verify SCD and to gauge if their pain is real, even if the condition is well-documented in their medical records. This delay in treatment leads to individuals experiencing more unnecessary pain.

Another common participant experience was being perceived by health care providers as “addicted to the [pain medication] drugs,” “drug-seeking,” “drug-dependent,” and “pharmacy hopping,” which often came from emergency department nurses and physicians, from some of their routine providers and staff in the outpatient clinic where they receive care, and from pharmacies. It was a common experience for health care providers to communicate these perceptions directly to patients. Some of the participants indicated that they were perceived to abuse prescription pain medication especially if they had switched pharmacies for any reason (i.e., felt that the pills were “better” at a different pharmacy), or if there was any type of mistake they made with prescription medications. One participant indicated that their physician stopped medication that worked for them because of one (unspecified) mistake that occurred after many years of taking the medication without incident.

Some participants also experienced providers recommending that they take Tylenol or Motrin instead of morphine or oxycodone for their pain. Participants indicated that these medications do not alleviate their pain. For the individuals in these focus groups, this recommendation to take over-the-counter medication is further evidence that providers do not understand the nature of their pain.

To avoid mistreatment by providers and the assumption that they are abusing drugs, some participants reported that they delay going to or do not go to the emergency department at all when experiencing pain. Some participants also noted they do not openly communicate with their providers when they run out of prescription pain medication. This avoidance of the health care system leads to a delay in treatment or no treatment at all, which can exacerbate the pain episode and lead to a pain crisis.

Quality of and Satisfaction with Care

Another subtheme that emerged from the data related to the overall quality of and satisfaction with care that individuals living with SCD receive is perceived discrimination. Some participants noticed the differential treatment based on race, “I think, sometimes, they [health care providers] look at treatment as, uh—it should be colorblind, but it’s not… When I’m in emergency room… [a] person that might be Caucasian, they come down, they get more general care than I would get.” The experience of being perceived as and, in some cases, directly told they are drug-seeking combined with the experience of receiving inadequate care resulted in participants feeling disrespected by their providers and health care system. For example, one participant indicated, “Some individuals don’t care… Saying your-your pain is not sickle cell pain. And you-you know that person don’t care for you. If you can say that about my painful situation that I’m goin’ through, that I’m sufferin’— that I been goin’ through—for all my life – what makes me think that you have respect.” Another reported having been told by an intern in the emergency department that they could “get up and get out” because the intern was not going to give them anything else, and another participant indicated a similar experience. One participant wished that providers would see individuals living with SCD more holistically rather than just manifesting symptoms of a disease, that they are “not just sitting at home poppin’ opioids and that’s it,” and that they have jobs that are sometimes physical in nature, which could exacerbate their pain.

One participant wished that there was assistance with getting medications for people with SCD because some do not have health insurance and the cost of medication is prohibitive. For these individuals, there is pressure to work, but due to pain, they may be unable to work, and some do not have medication that could help. There was a sentiment that because of the way that providers treated them, in terms of questioning the validity of their pain, providers did not respect them or care for them. There also was a perception that some health care programs (i.e., a program at an affiliated hospital) for SCD were being closed because most individuals experiencing the disease are persons of color.

Finally, there was the perception that individuals living with SCD were not being referred to or recommended for available programs (i.e., summer camp for seriously ill children and their families) because of a lack of knowledge about the disease or the services and support for which individuals living with SCD are eligible. Participants believed that discrimination and bias also occurred based on insurance type. They felt that individuals with private insurance received care much faster than those without insurance.

Perceptions of the Reasons for Health Care System and Health Care Provider Discrimination and Bias

Participants felt that SCD-related discrimination and other forms of bias in the health care system and by providers, physicians, advanced practice providers, and nurses occur due to (1) a lack of knowledge about SCD; (2) SCD affecting Black people and people of color; (3) SCD being a costly disease; (4) providers believing that patients may have shortened lifespan; and (5) increased pressure on physicians to address the opioid crisis.

One participant felt that providers do not know what SCD is, partially because the disease is experienced primarily by Black/African American and Latin people in America. Thus, the disease is not seen as a major health care issue in America. Several participants echoed this sentiment indicating that SCD does not get as much attention as other diseases, such as cancer, even though they experience some of the same symptoms as people with these diseases, “…they need to put our disease [sickle cell disease] out there a little bit more…I feel like we go through some of the stuff that cancer patients go through, so why we can’t get the same respect?” They felt that individuals living with leukemia, for example, received more attention and treatment right away and were a priority in the emergency room compared to individuals living with SCD.

Several participants reported that in addition to discrimination when they seek treatment for SCD, they experience medical discrimination because of their race. One participant noted “I feel like I’m discriminated against because of, um—of my race or somethin’.” Another stated “When I’m in emergency room, I know this person that might be Caucasian, they come down, they get more general care than I would get. It’s like, oh, okay, what’s the problem today? That—that’s part of society.”

Other perceptions of discrimination included the cost of sickle cell treatment and the sense that as patients they are not worth investing in by the medical system. One participant indicated, “Maybe they think they [individuals living with sickle cell disease] won’t live longer…People just talk, you could tell by the way they act you could tell. They don’t think you will live longer, so they just push you there. If you make it, good. If you don’t, it’s okay. No surprise.” Finally, participants recognized that physician behaviors toward individuals living with SCD may be due to the opioid crisis and pressure that physicians face not to prescribe or further contribute to the crisis.

Recommendations to Address Discrimination in the Health Care System

Participants were asked what they think could be done to address discrimination in the health care system for patients living with SCD and what health care team behaviors would help to minimize patients’ feelings of discrimination. They felt that to address the discrimination and bias experienced, improve patient-provider interactions, and receive better care for their SCD, health care providers need more and better education about SCD. They provided the following specific recommendations.

First, participants felt that providers could obtain direct feedback from patients, listen to patient experiences, and somehow “walk in your [patient’s] shoes” and gain a deeper understanding of the pain experienced by some individuals with SCD. Second, participants felt that providers and patients could participate in a “doctor-patient roundtable” where providers and patients talk to each other, see each other’s perspectives, and provide feedback to each other. Third, participants indicated that providers could learn from each other, such that providers who specialize in SCD could train and educate other physicians (e.g., emergency department physicians in particular), and physicians of color who have direct experience with SCD could educate other physicians. Finally, participants recommended that providers receive additional education about the nature of pain associated with SCD, the diversity within the SCD patient population, the stereotypes about opioid addiction (i.e., who is most likely to misuse opioids), and the signs and symptoms of individuals who are experiencing an exacerbation of their disease, particularly for providers in the emergency department.

Relationship with Providers

Participants were asked about their relationship with their health care providers, including communication with their provider, sense of trust or the expectation that their provider will do the best that they can for them, and feelings of respect. Participants gave feedback regarding relationships in the health system emergency department, the inpatient unit, and the clinic where participants receive their health care.

Communication

There was a consistent theme that providers do not always listen to what patients living with SCD have to say, particularly regarding the nature of their pain and its management. Participants felt as though they must repeat themselves, and sometimes, yell to get providers to hear and to understand how much pain they are in and the type of treatment they would like. Participants felt frustrated with the failure of some providers to return calls in a timely manner, “The only—w-well, one thing I have a very, very big issue with is, when I call the clinic, let it be at 9:30 or 10:00 in the mornin’, and I don’t get a call back from my provider all the way until 3:00 or 3:00 in the afternoon.” While they understand that providers have other patients, they would like someone to call them back in a reasonable timeframe. Some participants reported liking the health systems’ secure online portal that gives patients personalized access to portions of their electronic medical record and enables patients to manage their care.

Participants like physicians with whom they can talk honestly with and with whom they feel listened to. A consistent theme was that patients learned to stand up for and advocate for themselves so that providers do not “run over” patients so much. Some participants have seriously considered terminating their care at the health center to go elsewhere due to being treated disrespectfully or having disagreements about their care. One participant mentioned the need for a support group for individuals living with SCD so patients could air their concerns.

Sense of Trust in Health Care Providers

Participants were asked if they trusted their health care provider to guide the treatment for SCD. Focus group facilitators defined trust as a set of expectations that your health care provider will do the best for you. Participants also were asked if they feel supported by their health care provider in helping them manage/control symptoms associated with SCD. There was variability in participants’ trust in their providers. Some participants were very trusting and had not experienced challenges with their providers, and others had negative experiences (i.e., lack of confidentiality, negative provider attitude toward patient) with their providers and lacked trust, while others had mixed feelings.

While most of the participants indicated that they experienced discrimination with some aspect of their health care, most also had positive things to say about providers. When trust existed, it was often built through open, straightforward, and honest discussions between patients and providers. Some participants felt respected by their providers and reported the ability to have “real” conversations with their providers. For example, “You know, sometime people can see when you a little down, like nobody really cares about the sickle cell. It’s like, well, okay, let me keep it movin’, and that’s it. Some of ‘em, they stop, have a conversation and it makes you feel better.”

Trust was also created through physicians effectively taking care of patients when they are sick and during medical crises and providing holistic care. There was a sentiment expressed in the groups that good providers and physicians take care of their pain, “…but you know a good, um, provider or doctor that take care of your pain that the one that cares. You know the one that care about what he does for you, that he desire to do—get you a pillow or even provide oxygen for you. Showin’ that you—that he do care because they-they know oxygen will alleviate—will help to alleviate the pain— along with the pain medication and the-the liquids that they give you.” One participant felt as though they were treated holistically, for example, when their use of alcohol was addressed, and their health care provider wanted them to talk with someone about it. Finally, participants expressed that trust was fostered when providers help patients with other aspects of their lives, such as getting their identification card or getting them back into school.

On the other hand, some participants shared several incidents in which they felt disrespected by providers. For instance, one individual recalled that a physician entered their inpatient room with trainees and stated that the reason that he did not want to give the participant a port was because of street drugs, which incorrectly connoted that the participant used illicit drugs. Other examples of situations that led to participants feeling disrespected and invalidated included when providers do not ask patients what their life is like living with SCD, when they indicate that the patient’s pain is not “typical of sickle cell pain” and do not believe the patient’s self-reported pain, and when they are impatient with the patient’s questions.

The opioid epidemic also has influenced the patient-provider relationship, “Um, at one time, I did [trust my provider] a lot, and, uh, now, I be skeptical. I’m like, ‘Are you for my best interest, or you for the medical side?’ Like I said, it only comes down to me cuz I watch what’s goin’ on with the opioid thing. That’s a big thing with medical field right now. I think a lotta doctors are scared like, if I keep prescribin’ this to this patient, it’s gon look like I’m just passin’ this med off. It’s not even like that.”

Power Dynamics

Participants recounted several incidents that highlight the power dynamics between patients and providers, which typically related to pain, medication management, and treatment regime. There were differences in perspectives and sometimes participants had disagreements with their providers. Referencing providers, one participant stated, “And they’ll just feel like if they take something from you, that they have more power over you. And regardless of how much pain you’re in, they’ll just, like—oh, you know, it don’t matter. Or they’ll think that you’re more into the streets and stuff like that when you’re really not. Like, and put you into a category even though…it don’t even fit.”

Others felt that when emergency department physicians lack SCD knowledge and, as a result, do not provide the appropriate care, the physicians seem to become angry that patients come back to the emergency department. Additionally, one participant reported feeling as though visits to the hospital were being held against them, “… the way they address us, it kinda makes us feel like we don’t even wanna go to the hospital for help because they hold that against us when we come back, and they’re like, ‘Oh, well, we notice you weren’t in the hospital. Like, da, da, da, da, da, da.’”.

Finally, another participant said, “I gotta walk on eggshells. And there’s certain times that they feel like they have the power to take stuff away from you because they feel that you don’t need it or however or to punish you. And you’re—you don’t know what I’m going through and what pain I’m going through. And then I can’t go to the emergency room because you have it to the point that I’m not allowed to get any help. And that’s a lot. That’s wrong that you feel, because we had a disagreement—because we had a disagreement that you feel like, okay, well, I’ll stop your meds. Or, you know, you go to emergency room, and I’m gonna tell them that, you know, you’re not allowed to get certain things.”

Overall Satisfaction with Providers

Finally, overall satisfaction with providers varied. Some were satisfied with their providers, some were not, and some were on the fence. Provider satisfaction was related to the degree to which providers acknowledge the patient’s pain, help the patient speak for themselves, listen to the patient and understand where they are coming from, and have someone return phone calls in a timely manner.

Participants expressed frustration with feeling like their care was a “revolving door” and that there is “no consistency in care.” They felt that a downside to their provider being at a teaching hospital is that they often see new and different physicians. As a result, they had to tell their stories repeatedly, and wished that physicians would review their charts or shadow the previous physicians to learn about their history and experience of SCD. Another aspect of this was the continuously changing medical regimes. Several participants reported being so frustrated with changing medical regimes, feeling that they were not being heard, and/or repeated negative experiences that they considered leaving the hospital system and finding another provider, “There’s times that I’ll get upset, and I’ll be wanting to leave, but I’m just like, this is the only hospital I know.”

Some participants’ satisfaction was colored by the feeling that some physicians put everyone living with SCD in the same category, compare patients, and penalize one patient because of the actions of another patient. To facilitate better patient-provider relationships, participants indicated that providers need to look at individuals with SCD as individuals and not always as a part of a group in that there are individual differences in experiences of the disease, treatment needs, and reactions to treatments, and they also need to return calls in a timely manner.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a qualitative thematic analysis of patients’ perceptions of their care in a specialty SCD clinic associated with a tertiary medical center in the Northeastern USA. Participants in these focus groups specifically described their experiences with discrimination and bias, their relationships with providers, and the treatment and care they received in this medical system. Participants described experiences of bias related to both their diagnosis of SCD and their race, and often felt stereotyped as “drug-seeking” or addicted to opioids. They also identified lack of understanding and poor communication, both between providers and patients and between different aspects of the medical center (e.g., clinic to ED) as problematic and leading to delays in care. They also noted poor consistency in their care, which they associated with frequently changing staff members and lack of education of some staff about SCD. Participants broadly suggested increased education about SCD, more opportunities for open dialogue between patients and providers, more responsive and forthright communication, and tailoring care to the needs of each individual patient as ways the medical center might improve the care of patients with SCD.

Our findings are consistent with those of prior studies in individuals living with SCD and other patient populations with chronic illness that suggest trust and poor provider-patient communication are important factors via which perceived discrimination impacts health care quality. Several prior studies have found that patients seeking treatment for SCD pain crises experience long delays in receiving pain medications, undertreatment of pain, accusations of drug-seeking behavior, lack of individualized treatment, and concerns that medical staff lack understanding of or have negative attitudes regarding SCD [8, 29,30,31,32]. Patients in our study reported they would often avoid care due to issues with trust, bias, and communication, leading to worsening of their pain. This aligns with others’ findings in the literature. Prior studies have identified that discriminatory experiences in the health care setting among individuals living with SCD are associated with decreased patient trust in medical professionals, which in turn is associated with a greater likelihood of nonadherence to physician recommendations [22]. That group also identified associations between perceived disease-based discrimination and self-reported pain [23] and poor provider communication [33], which in turn is associated with decreased trust in the medical profession [13] in patients with SCD. Given the thematic similarities between our study and others, it may be possible to apply recommendations more broadly. However, there is also evidence that there are differences in trust and related behaviors based on location. One study on patients with SCD demonstrated significantly more concerning behaviors such as self-discharges and disputes with staff in Baltimore compared to London [34]. Thus, other health care systems should assess the needs of patients with SCD at their locale before broadly applying interventions that may have worked elsewhere.

Evidence from other populations with chronic diseases with significant stigma supports the concept that improvements in patient-provider trust can improve outcomes. For example, in patients with HIV, measures of the patient-physician relationship were positively correlated with anti-retroviral medication adherence [35]. Similar relationships between trust and adherence have been seen with hypertension [36] and colon cancer screening [37]. One study specifically found that trust mediated 39% of the effects of discrimination on medication adherence for hypertension [38], suggesting trust-building may be particularly important in groups that face discrimination. Trust in physicians may also moderate the impact of cost-related medication nonadherence [39].

Based on recommendations made by the focus group participants and the themes that emerged from our analysis, several recommendations were made to improve the treatment experience in our medical system. Providers who often see patients with SCD should be provided with ongoing opportunities to learn about SCD and its treatment. This is in line with the literature [40], and recommendations for the best practices of the management of SCD are well established [41]. Reports of discrimination and bias should be addressed at both individual and systematic levels, including additional training on implicit bias and the development of policies to identify and respond to these experiences. Providers should listen to patients’ accounts of their pain, recognize their experiences of discrimination, and refrain from minimizing their experiences. Providers should acknowledge patients’ frustrations, including with personal factors such as bias and frequent transitions of care as well as environmental factors such as overcrowding and noise, and their individual concerns should be addressed. Patients’ pain should be treated in a timely manner, through the use of medications, IV fluids, oxygen, and heated blankets. Hospitals should ensure that their emergency departments follow the evidence-based management recommendations by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute on the management of SCD [41], which outline the recommended timeline from arrival and triage to first administration of pain medication. Social work and case management support to address needs such as insurance, identification, and employment, as well as providing connections to other resources for patients with SCD in the community, may help build trust with the medical team. Forums to allow dialogue between patients and providers should be considered to improve communication and address the power dynamic.

There are notable limitations to our study. Our sample size is 18 participants, and all are patients within a single SCD clinic and health system. Within that sample, there may be self-selection bias among patients who chose to participate. Patients with more distrust for the system may have been less inclined to join a research study, for example. We also do not have specific outcome data relating to participant’s past experiences, which could further characterize our sample. The purpose of this study is to describe the lived experience of individuals living with SCD. As such, it does not provide the perspectives of medical providers or the complexities of pain management from a medical standpoint.

Conclusions

This study finds that perceived discrimination, poor trust with many providers, and perceived differences in the quality of treatment are overarching concerns in patients with SCD. Participants identified lack of knowledge about SCD, bias based on race and diagnosis, poor communication and not feeling heard by providers, the ongoing opioid crisis, and systemic issues including pressures on providers to see many patients and hospital overcrowding as potential contributing factors to these issues. These findings are largely consistent with other studies of patients with SCD, and interventions that improve patient-provider trust may help improve treatment adherence and, in turn, health outcomes.

Data Availability

Upon request, limited by nature of study and participant privacy protection.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(4 Suppl):512–21.

Fu Y, Andemariam B, Herman C. Estimating sickle cell disease prevalence by state: a model using US-born and foreign-born state-specific population data. Blood. 2023;142(Supplement 1):3900–3900.

Platt OS, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease – life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(23):1639–44.

Shah N, et al. Treatment patterns and economic burden of sickle-cell disease patients prescribed hydroxyurea: a retrospective claims-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2019;17(1):155.

Steinberg MH, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on mortality and morbidity in adult sickle cell anemia: risks and benefits up to 9 years of treatment. JAMA. 2003;289(13):1645–51.

Leonard A, Tisdale JF, Bonner M. Gene therapy for hemoglobinopathies: beta-thalassemia, sickle cell disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2022;36(4):769–95.

Lovett PB, Sule HP, Lopez BL. Sickle cell disease in the emergency department. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2017;31(6):1061–79.

Maxwell K, Streetly A, Bevan D. Experiences of hospital care and treatment seeking for pain from sickle cell disease: qualitative study. BMJ. 1999;318(7198):1585–90.

Jenerette C, Funk M, Murdaugh C. Sickle cell disease: a stigmatizing condition that may lead to depression. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2005;26(10):1081–101.

Ballas SK, et al. Opioid utilization patterns in United States individuals with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2018;93(10):E345-e347.

Lattimer L, et al. Problematic hospital experiences among adult patients with sickle cell disease. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(4):1114.

Wesley KM, et al. Caregiver perspectives of stigma associated with sickle cell disease in adolescents. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(1):55–63.

Haywood C Jr, et al. The association of provider communication with trust among adults with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):543–8.

Haywood C, et al. Hospital self-discharge among adults with sickle-cell disease (SCD): associations with trust and interpersonal experiences with care. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):289–94.

Ezenwa MO, et al. Perceived injustice predicts stress and pain in adults with sickle cell disease. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(3):294–306.

Adams LB, et al. Medical mistrust and colorectal cancer screening among African Americans. J Community Health. 2017;42(5):1044–61.

Lillard JW Jr, et al. Racial disparities in Black men with prostate cancer: a literature review. Cancer. 2022;128(21):3787–95.

Hood AM, et al. The influence of perceived racial bias and health-related stigma on quality of life among children with sickle cell disease. Ethn Health. 2022;27(4):833–46.

Nelson SC, Hackman HW. Race matters: perceptions of race and racism in a sickle cell center. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(3):451–4.

Lockwood KG, et al. Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular health disparities: a multisystem review and health neuroscience perspective. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1428(1):170–207.

Britt-Spells AM, et al. Effects of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms among Black men residing in the United States: a meta-analysis. Am J Mens Health. 2018;12(1):52–63.

Haywood C, et al. Perceived discrimination, patient trust, and adherence to medical recommendations among persons with sickle cell disease. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1657–62.

Haywood C, et al. Perceived discrimination in health care is associated with a greater burden of pain in sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):934–43.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG, Naturalistic inquiry. 1985: Sage

Strauss A, Corbin J, Grounded theory methodology: an overview., in Handbook of qualitative research, N.K. Denzin and Y.S. Lincoln, Editors. 2000, Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA. 273–285

Cullen MM, Brennan NM, Grounded theory: description, divergences and application. Accounting, Finance & Governance Review, 2021. 27

Thornberg R, Dunne C, Literature review in grounded theory., in The SAGE handbook of current developments in grounded theory, A. Bryant and K. Charmaz, Editors. 2019, Sage: London, UK

Creswell JW, Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed. 2007, London, UK: Sage

Harris A, Parker N, Barker C. Adults with sickle cell disease: psychological impact and experience of hospital services. Psychol Health Med. 1998;3(2):171–9.

Murray N, May A. Painful crises in sickle cell disease–patients’ perspectives. BMJ. 1988;297(6646):452–4.

Butler DJ, Beltran LR. Functions of an adult sickle cell group: education, task orientation, and support. Health Soc Work. 1993;18(1):49–56.

Alleyne J, Thomas V. The management of sickle cell crisis pain as experienced by patients and their carers. J Adv Nurs. 1994;19(4):725–32.

Haywood C, et al. An unequal burden: poor patient-provider communication and sickle cell disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96(2):159–64.

Elander J, Beach MC, Haywood C Jr. Respect, trust, and the management of sickle cell disease pain in hospital: comparative analysis of concern-raising behaviors, preliminary model, and agenda for international collaborative research to inform practice. Ethn Health. 2011;16(4–5):405–21.

Schneider J, et al. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1096–103.

Jones DE, et al. Patient trust in physicians and adoption of lifestyle behaviors to control high blood pressure. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):57–62.

Born W, et al. Colorectal cancer screening, perceived discrimination, and low-income and trust in doctors: a survey of minority patients. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:363.

Cuffee YL, et al. Reported racial discrimination, trust in physicians, and medication adherence among inner-city African Americans with hypertension. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e55-62.

Piette JD, et al. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(15):1749–55.

Linton EA, et al. A survey-based needs assessment of barriers to optimal sickle cell disease care in the emergency department. Annal Emerg Med. 2020;76(3, Supplement):S64–72.

National Heart L, Institute B, Evidence-based management of sickle cell disease: expert panel report. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health, 2014;161

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff at the Adult Sickle Cell Program outpatient clinic at Yale New Haven Hospital for their efforts in recruiting focus participants and for arranging meeting space. We would like to thank the individuals receiving care at the Adult Sickle Cell Program outpatient clinic at Yale New Haven Hospital who participated in the focus groups.

Funding

The project was funded through the Sickle Cell Fund, Department of Psychiatry, Yale University School of Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cindy Crusto: conceptualization; methodology (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); review and editing. Joy Kaufman: conceptualization; methodology (equal; formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); writing—original draft (equal); review and editing. Zachary Harvanek: writing—original draft; review and editing. Christina Nelson: formal analysis, investigation. Ariadna Forray: conceptualization (lead); funding acquisition; methodology; supervision; writing—original draft (equal); review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The Human Research Protection Program at Yale University approved (IRB protocol ID#2000023730) and provided oversight of the study with regard to human subjects protections.

Consent to Participate and for Publication

Participants gave verbal consent for participation in the focus group and permission to publish.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Crusto, C.A., Kaufman, J.S., Harvanek, Z.M. et al. Perceptions of Care and Perceived Discrimination: A Qualitative Assessment of Adults Living with Sickle Cell Disease. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02153-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-024-02153-3