Abstract

Background and Objectives

The Dysfunctional Voiding and Incontinence Scoring System (DVISS) is a validated tool to evaluate lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD) severity in children. DVISS provides a quantitative score (0–35) including a quality-of-life measure, with higher values indicating more/worse symptoms. Clinically, variability exists in symptom severity when patients present to pediatric urology with LUTD. We hypothesized that symptom severity at consultation varied based on race, gender, and/or socioeconomic status.

Methods

All urology encounters at a single institution with completed modified DVISS scores 6/2015–3/2018 were reviewed. Initial visits for patients 5–21 years old with non-neurogenic LUTD were included. Patients with neurologic disorders or genitourinary tract anomalies were excluded. Wilcoxon rank sum tests compared scores between White and Black patients and between male and female patients. Multiple regression models examined relationships among race, gender, estimated median household income, and insurance payor type. All statistics were performed using Stata 15.

Results

In total, 4086 initial patient visits for non-neurogenic LUTD were identified. Median DVISS scores were higher in Black (10) versus White (8) patients (p < 0.001). Symptom severity was higher in females (9) versus males (8) (p < 0.001). When estimated median income and insurance payer types were introduced into a multiple regression model, race, gender, and insurance payer type were significantly associated with symptom severity at presentation.

Conclusions

Race, gender, and socioeconomic status significantly impact LUTS severity at the time of urologic consultation. Future studies are needed to clarify the etiologies of these disparities and to determine their clinical significance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract dysfunction (LUTD), bladder and bowel dysfunction, and dysfunctional elimination syndrome all describe functional disorders of the lower urinary tract without clear neurologic or anatomic etiologies. These disorders may include overactive bladder, voiding postponement, underactive bladder, dysfunctional voiding, primary bladder neck dysfunction, giggle incontinence, vaginal reflux, urinary frequency, and enuresis [1,2,3]. LUTD is the most common reason for referral to the pediatric urologists and studies across ethnicities estimate the prevalence rate to be as high as 17–22% among school aged children [4, 5].

Several symptom questionnaires have been developed to better quantify symptom severity in pediatric patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) [6, 7]. Since 2006, our pediatric urology division has used a slight modification of the Dysfunctional Voiding and Incontinence Scoring System (DVISS) for all pediatric patients with LUTD [8, 9]. The DVISS is a validated tool to evaluate lower urinary tract and bowel symptoms in children, which includes a quality of life or degree of bother question. A quantitative score (0–35) is provided with higher values indicating more/worse symptoms and a score of greater than 8.5 was shown to have a 90% sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis bowel and bladder dysfunction in boys and girls [8]. This 14-question questionnaire has been found to have high diagnostic accuracy when compared to physician assessment of bladder and bowel dysfunction as well as excellent internal reliability [7, 10]. A slight modification of the DVISS has been previously published with the minor change of adding infrequent voiding as an option for the question on urination frequency (Fig. 1) [9]. The use of this instrument assists pediatric urologists in determining the severity of a patient’s symptoms at the time of presentation and allows physicians to better assess for improvement over time.

Patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction are often referred to a pediatric urologist to confirm the absence of a neurologic or anatomic cause of these symptoms and to assist with management of these disorders. Significant variability exists in the severity of symptoms with which patients present to pediatric urology with these disorders. Presumably, this variability may be related to the family’s perception of whether these symptoms are problematic, cultural expectations of when children should be continent, the comfort of primary care clinicians with caring for these issues, and their perception of whether or not the presenting symptoms are severe enough to merit urologic consultation.

Studies throughout the medical literature have shown the impact of race, gender, and socioeconomic status on health care access and utilization [11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These disparities often lead to differences that can significantly impact healthcare expenditure and patient outcomes, including quality of life [18]. This study sought to determine whether the symptom severity in patients with bladder and bowel dysfunction at the time of presentation to a pediatric urologist varies depending on the patient’s race, gender, and/or socioeconomic status. We hypothesized that female gender, African-American race, and lower socioeconomic status would be associated with higher DVISS scores at time of initial presentation to a pediatric urologist.

Patients and Methods

All urology encounters at a single institution with a completed modified DVISS score (Fig. 1) between June 2015 and March 2018 were reviewed. Only the first visit for each patient was included in this analysis. All International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes that had been associated with these visits were obtained. Only visits with a primary ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis code related to LUTD (e.g., urgency, incontinence, frequency, constipation) were included (listed in Table 1). Any patients with diagnosis codes related to neurologic disorders (e.g., spina bifida), genitourinary tract anomalies, or complex medical syndromes that have been associated with LUTD were excluded (listed in Table 2).

Race, gender, zip code, and insurance payer type (self-pay, financial assistance/Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), private/military, and international) were extracted from the electronic medical record for each patient. Limited numbers of patients who self-identified as races other than White or Black precluded our ability to include them in our analysis when comparing DVISS scores among racial groups. Data from the 2013–2017 American Community Survey was used to determine median household income by zip code (as provided by the US Census Bureau through the American FactFinder website). International patients (n = 16) were excluded from our analyses.

Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare modified DVISS scores between White and Black patients as well as between male and female patients. Multiple regression models were used to determine how race, gender, estimated median household income, and insurance payer type affected LUTS severity at the time of presentation to urology. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 15 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

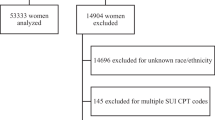

A modified DVISS score was available for a total of 11,758 pediatric urology visits between June 2015 and March 2018. A total of 5645 of these visits had a primary diagnosis code related to LUTD. From these visits, 4226 unique patients were identified. In total, 140 patients had neurologic, genitourinary, or syndromal disorders that excluded them from the final analysis, leaving a total of 4086 patients with an initial visit for non-neurogenic LUTD (Fig. 2). Population characteristics can be found in Table 3.

When symptom severity scores were compared between Black or African-American patients and White patients, the median modified DVISS scores were 10 (IQR 7–15) for Black or African-American patients and 8 (IQR 4–13) for White patients (p < 0.001). When gender differences were examined, the median DVISS scores were found to be 9 (IQR 4–14) for females and 8 (IQR 4–13) for males (p < 0.001). The bother score (as determined by the last question in the questionnaire) was significantly higher in females than in males (p = 0.004). There was no significant difference in bother score between Black or African-American and White patients (p = 0.072). Multiple regression was used to examine how race, gender, and estimated household income by zip code affect symptom severity at the time of initial presentation to urology. The addition of estimated median household income did not eliminate the significant impact of race and gender on LUTS severity at the time of initial visit with urology. In this model, Black or African-American patients would present with DVISS scores 1.59 points higher than White patients (p < 0.001). Female patients would have scores 0.58 points higher than male patients (p = 0.006). Additionally, a $10,000 increase in estimated income was associated with a 0.1 point decrease in symptom severity score (p = 0.015) (Table 4). Upon adding insurance payer type to the model, race, gender, and insurance payer type all had significant relationships with symptom severity at the time of initial presentation to a urologist. However, the effects of estimated income on symptom severity were no longer found to be significant (p = 0.591). In this model, even after factoring in income status, Black or African-American patients presented with DVISS scores 1.0 point higher than White patients (p < 0.001), females presented with scores 0.6 points higher than males (p = 0.004), and financial assistance/Medicaid/CHIP patients presented with DVISS scores 1.0 points higher than self-pay patients (p < 0.001) and 1.8 points higher than private or military insurance patients (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Discussion

Race, gender, and socioeconomic status all appear to be independently associated with symptom severity in children presenting for the first time to a pediatric urology with a complaint of LUTD. Racial disparities in triage and referrals for higher level of care have been noted in many studies across various medical fields [14,15,16,17]. One study examining emergency department waiting times in acute stroke patients revealed significantly longer waiting times for Black patients when compared to White patients. Black patients were also more likely to wait longer than the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) recommended 10 min to see an emergency physician from the time of presentation [15]. These observed racial disparities raise the question of whether or not unconscious bias may play a role in perceived severity of patient symptoms when the decision needs to be made regarding how urgently the individual needs to be seen for further evaluation.

In the Journal of General Internal Medicine, Chapman and colleagues discuss physician susceptibility to implicit bias. Physician training tends to emphasize group level information such as population risk facts, and the uncertainties and time pressures surrounding the diagnostic process can lead to a reliance on stereotypes for efficiency in decision-making. Additionally, a physician’s vast knowledge of scientific data can create a strong belief in one’s own personal objectivity, which can ironically lead to bias in decision-making [19]. This potential for implicit bias within clinical practice was demonstrated in a study performed in Boston, MA, where researchers examined the role of unconscious bias among physicians when making thrombolysis recommendations for Black and White patients with acute coronary syndromes. An internet-based tool with a clinical vignette of a patient presenting to the emergency department with an acute coronary syndrome in addition to a questionnaire measuring explicit (conscious) bias and three Implicit Association Tests (IATs) were sent to internal medicine and emergency medicine residents across four academic medical centers. The IATs revealed implicit stereotypes of Black Americans as less cooperative when compared to White Americans. As these implicit biases increased, physicians’ likelihood of treating White patients and not treating Black patients with thrombolysis also went up [20].

Pediatric patients are not protected from the effects of implicit bias. Multiple studies reveal the impact of race and ethnicity on treatment of pain in pediatric patients. The treatment of pain due to fractures, abdominal pain, and appendicitis in minority children has been shown to involve less pain medication, which may suggest variability in the threshold to treat moderate to severe pain based on race and ethnicity [21,22,23]. In fact, Raphael and Oyeku discuss the importance of addressing these implicit biases that clearly color the care of our vulnerable patients in their recent commentary in Pediatrics [24].

In this study, it is possible that the differences seen between Black and White patients at the time of presentation to pediatric urology were related to differences in cultural expectations related to toileting or cultural perceptions with regard to when a bothersome urinary symptom warrants a specialist’s evaluation. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that implicit bias may play a role in the decision to consult a specialist.

Gender or sex disparities have also been noted in the medical literature with regard to how subjective complaints are interpreted by health care providers. In the pediatric population, the parents’ and/or providers’ perceptions of whether a child is exaggerating or minimizing their symptoms could directly affect the decision to seek higher levels of care. In a study examining health care providers’ judgments of trustworthiness among chronic pain patients, female patients were estimated to have less pain and be more likely to exaggerate their pain when compared to male patients [25]. Resultantly, female patients were less likely to be recommended analgesics and more likely to be recommended psychological treatment [25]. Therefore, the higher symptom severity scores seen in girls with LUTD at the time of presentation to pediatric urology may be reflective of how their subjective symptoms are being perceived by parents, caregivers, and primary care providers as being exaggerated. Alternatively, cultural expectations regarding the prevalence and therefore “normalcy” of LUTS among girls may lead to higher thresholds for referral. The difference in DVISS scores at the time of presentation to urology may also be related to pathophysiologic differences in how symptoms present in girls versus boys and a resultant tendency for LUTD to initially present with higher severity in girls.

Estimated median household income by zip code was initially found to significantly affect severity scores when examined alongside race and gender. However, once insurance status was included in the analysis, this effect was lost. This loss of significance may be related to the fact that income levels even within the same zip code can be vastly variable. Future research using census tract data could potentially show that estimated income remains significant when the data obtained has a higher level of accuracy. Based on the available data, it appears that income levels may only be relevant due to their relationship with insurance type as those with lower financial means may need to rely on insurance plans available through state or federally funded programs such as Medicaid and CHIP. Patients who have not been able to obtain one of these plans also turn to financial assistance programs through the hospital. Patients with financial assistance plans, Medicaid, or CHIP tend to present with more severe LUTS when compared to self-pay patients and when compared to patients with private or military insurance. This difference may be related to differing thresholds regarding when a problem is considered severe enough to seek specialty care related to ease of access through various insurance plans. It is also possible that referrals and insurance authorizations take more time to process among patients with financial assistance or state/federally funded programs, leading to a delay in arrival to a pediatric urology clinic.

This study has several limitations including its retrospective design and use of diagnosis codes to query the electronic medical record. Incorrect diagnoses and patients ultimately diagnosed with a neurogenic or anatomic anomaly may also have been included inadvertently. Use of zip code for income estimation is also limited as discussed above. Ultimately, the difference in DVISS scores among these various populations was 2 points or less. While these differences were noted to be statistically significant, the clinical significance of these score differences is less clear. The optimal DVISS score cutoff to distinguish children with voiding abnormalities from those who are normal has been previously reported to be 8.5; however, the clinical meaningful difference in score has not been previously reported.8 While there is concern that these differences in symptom severity at the time of presentation may translate to longer time to resolution or higher levels of patient distress, future studies are needed to clarify how these differences may or may not impact the course of the disease. Additionally, our study was conducted at a free-standing children’s hospital with a large referral population including patients seeking second and third opinions. Therefore, it is unclear how generalizable our results are.

Conclusions

Race, gender, and socioeconomic status all significantly impact the severity of LUTS in patients who are initially seen by pediatric urology. While socioeconomic status clearly appears to play an important role in this patient population’s access to pediatric urology, it does not negate the role of race and gender as demonstrated by our model. Future studies are needed to clarify the reasons behind why these disparities exist and to determine the clinical significance of these findings. Additionally, these findings may merit the initiation of quality improvement and/or community outreach projects to enhance the availability of resources to potentially at-risk populations.

Abbreviations

- LUTD:

-

Lower urinary tract dysfunction

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- DVISS:

-

Dysfunctional Voiding and Incontinence Scoring System

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- CHIP:

-

Children’s Health Insurance Program

- NINDS:

-

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- IAT:

-

Implicit Associations Test

References

Austin P, Gino V. Functional disorders of the lower urinary tract in children. In: Wein A, Kavoussi L, Partin A, Peters C, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. 11th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Ltd; 2016. p. 3297–316.

Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the standardization committee of the international children’s continence society. J Urol. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.110

Nevéus T, von Gontard A, Hoebeke P, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: report from the Standardisation Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00305-3

Sureshkumar P, Jones M, Cumming R, Craig J. A population based study of 2,856 school-age children with urinary incontinence. J Urol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.044

Vaz GT, Vasconcelos MM, Oliveira EA, et al. Prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms in school-age children. Pediatr Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00467-011-2028-1

Jiang R, Kelly MS, Routh JC. Assessment of pediatric bowel and bladder dysfunction: a critical appraisal of the literature. J Pediatr Urol. 2018;14(6):494–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.08.010.

Altan M, Çitamak B, Bozaci AC, Mammadov E, Doğan HS, Tekgül S. Is there any difference between questionnaires on pediatric lower urinary tract dysfunction? Urology. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.055

Akbal C, Genc Y, Burgu B, Ozden E, Tekgul S. Dysfunctional voiding and incontinence scoring system: quantitative evaluation of incontinence symptoms in pediatric population. J Urol. 2005;173(3):969–73. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000152183.91888.f6.

Schast AP, Zderic SA, Richter M, Berry A, Carr MCS. Quantifying demographic, urological and behavioral characteristics of children with lower urinary tract symptoms. J Pediatr Urol. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.10.007

Goknar N, Oktem F, Demir AD, Vehapoglu A, Silay MS. Comparison of two validated voiding questionnaires and clinical impression in children with lower urinary tract symptoms: ICIQ-CLUTS versus Akbal survey. Urology. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.011

Wheeler SM, Bryant AS. Racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ogc.2016.10.001

Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1243

Brown ZD, Bey AK, Bonfield CM, et al. Racial disparities in health care access among pediatric patients with craniosynostosis. In: Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics. ; 2016. https://doi.org/10.3171/2016.1.PEDS15593

Eberly LA, Richterman A, Beckett AG, et al. Identification of racial inequities in access to specialized inpatient heart failure care at an academic medical center. Circ Hear Fail. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.119.006214

Karve SJ, Balkrishnan R, Mohammad YM, Levine DA. Racial/ethnic disparities in emergency department waiting time for stroke patients in the United States. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20(1):30–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.10.006.

Riad M, Dunham DP, Chua JR, et al. Health disparities among hispanics with rheumatoid arthritis: delay in presentation to rheumatologists contributes to later diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000001085

Schrader CD, Lewis LM. Racial disparity in emergency department triage. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(2):511–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.05.010.

Zhang X, Carabello M, Hill T, He K, Friese CR, Mahajan P. Racial and ethnic disparities in emergency department care and health outcomes among children in the United States. Front Pediatr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2019.00525

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1.

Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for Black and White patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5.

Goyal MK, Johnson TJ, Chamberlain JM, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in emergency department pain management of children with fractures. www.aappublications.org/news.

Johnson TJ, Weaver MD, Borrero S, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with management of abdominal pain in the emergency departmente858. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):851. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-3127.

Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):996–1002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1915.

Raphael JL, Oyeku SO. Implicit bias in pediatrics: an emerging focus in health equity research. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-0512

Schäfer G, Prkachin KM, Kaseweter KA, Williams ACDC. Health care providers’ judgments in chronic pain: the influence of gender and trustworthiness. Pain. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000536

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number KL2TR001879 (JPV), the Urology Care Foundation Rising Stars in Urology Research Award Program and Frank and Marion Hinman Urology Research Fund (JPV), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K08DK120934 (JPV). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Joan Ko conceptualized and designed the study, acquired the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Christopher Corbett acquired the data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Jason Van Batavia conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. Amanda Berry, Stephen Zderic, Dana Weiss, and Chris Long contributed to conception and design of the study, and revision of the article. Katherine Fischer revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Research was completed at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Division of Urology, Philadelphia, PA.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ko, J.S., Corbett, C., Fischer, K.M. et al. Impact of Race, Gender, and Socioeconomic Status on Symptom Severity at Time of Urologic Referral. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 10, 1735–1744 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01357-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-022-01357-9