Abstract

Purpose

We explored associations between clinical factors, including eating disorder psychopathology and more general psychopathology, and involuntary treatment in patients with anorexia nervosa. Our intention was to inform identification of patients at risk of involuntary treatment.

Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study combining clinical data from a specialized eating disorder hospital unit in Denmark with nationwide Danish register-based data. A sequential methodology yielding two samples (212 and 278 patients, respectively) was adopted. Descriptive statistics and regression analyses were used to explore associations between involuntary treatment and clinical factors including previous involuntary treatment, patient cooperation, and symptom-level psychopathology (Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) and Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)).

Results

Somatization (SCL-90-R) (OR = 2.60, 95% CI 1.16–5.81) and phobic anxiety (SCL-90-R) (OR = 0.43, 95% CI 0.19–0.97) were positively and negatively, respectively, associated with the likelihood of involuntary treatment. Furthermore, somatization (HR = 1.77, 95% CI 1.05–2.99), previous involuntary treatment (HR = 5.0, 95% CI 2.68–9.32), and neutral (HR = 2.92, 95% CI 1.20–7.13) or poor (HR = 3.97, 95% CI 1.49–10.59) patient cooperation were associated with decreased time to involuntary treatment. Eating disorder psychopathology measured by the EDI-2 was not significantly associated with involuntary treatment.

Conclusions

Clinical questionnaires of psychopathology appear to capture specific domains relevant to involuntary treatment. Poor patient cooperation and previous involuntary treatment being associated with shorter time to involuntary treatment raise important clinical issues requiring attention. Novel approaches to acute anorexia nervosa care along with unbiased evaluation upon readmission could mitigate the cycle of repeat admissions with involuntary treatment.

Level of evidence

Level III, cohort study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric disorder characterized by low weight, a distorted body image, and an ego-syntonic nature that makes treatment challenging [1,2,3,4]. Outcome is often poor and treatment avoidance [5], treatment dropout [6, 7], and post-treatment relapse are common [8]. Furthermore, dissent to undergo treatment is frequent resulting in involuntary treatment (IT), e.g., involuntary admission, detention, nasogastric tube feeding, involuntary medication, or restraint, for between 13 and 44% of patients on inpatient wards [9]. Involuntary admission and detention are similar, because they uphold that the patient has to be admitted or remain in hospital, whereas the other IT measures are more limited interventions that logically also result in the patient not being free to leave, but themselves represent more time-limited tangible interactions with treatment staff.

Several factors have been associated with IT in AN including female gender, both lower and higher socioeconomic status, younger age at first admission, early and late onset age, longer duration of illness or treatment, AN symptom severity in the form of a lower body mass index (BMI) and purging behavior, previous hospital admissions, psychiatric comorbidity (depression, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, autism spectrum disorders, and personality disorders), previous IT, self-harm, a history of abuse, lower psychosocial functioning, and lower IQ [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. These studies primarily concern involuntary admission, which to some extent can be considered a proxy for other IT measures [12, 18]. However, the clinical relevance of the factors in identifying patients at risk of IT is limited, as many patients with AN are female and young, and have comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, severe underweight, and purging behavior—and many do not require IT [9, 19, 20]. Moreover, legal routes to IT vary internationally [21], and accordingly, legal factors may moderate associations between clinical factors and IT, thereby complicating cross-country comparisons. Criteria for initiation of IT in Scandinavia are comparable [22]. Initiation of IT in Denmark requires the patient with AN to be in a state equivalent to psychosis and either in need of treatment to aid recovery or to pose a danger to self or others [23].

The literature on psychopathology symptoms associated with IT is sparse [15]. Ayton et al. [16] reported that IT in AN is associated with higher levels of depression (measured using the Beck Depression Inventory-II), whereas they found no association with eating disorder psychopathology (as observed on the Morgan–Russell scale) [16]. Watson et al. [24] found no differences in the scores on the Eating Disorder Inventory, Eating Attitudes Test-26, or Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 for patients with and without involuntary admission. Hence, symptom-level markers of IT still require exploration.

Although several clinical factors have been identified as severity markers increasing the risk of a severe illness course and treatment challenges in AN, they have not been tested in relation to IT. These factors include both eating disorder psychopathology and more general psychopathology. In addition to severe eating disorder symptoms such as severe underweight and purging [25,26,27,28,29], some eating disorder psychopathology symptoms (as measured by the Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2)) [30] have been associated with poorer outcome. Specifically, the subscale "maturity fears" has been associated with poorer outcome [25] and inpatient treatment dropout [31], "perfectionism" has been associated with poorer outcome [25], and "asceticism" has been associated with longer hospital stays [32]. A lower level of "body dissatisfaction" has been found to predict better treatment outcome [33]. Furthermore, cognitive features characteristic of AN have been suggested to affect patients' competence to consent to treatment [34], thereby complicating treatment and illness course.

With reference to general psychopathology, psychiatric and somatic comorbidity [35], including obsessive–compulsive personality [26] and depression [28], have been associated with a poorer outcome in AN. "Paranoid ideation" (as measured by the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R)) [36] has been found to predict treatment dropout [37]. Patients who are more motivated than others for recovery and display better interpersonal functioning have been shown to have better outcomes [29, 38], whereas family problems (measured as parental expressed emotion) have been associated with poorer outcome [29]. Moreover, therapeutic alliance may be important for treatment and post-treatment outcomes [39].

IT can be difficult for patients, staff, and relatives [40,41,42,43,44] and poses ethical questions [e.g., 45, 46]. Therefore, reducing IT is a work in progress [47,48,49,50,51] and improving identification and prevention of IT a necessity. Specifically, improving the ability of clinicians to identify patients at risk of IT as early as possible is important to intervene and prevent future IT [52,53,54]. In light of this and the limited evidence and research on associations between IT and specific clinical symptoms, we explore associations between IT and clinical factors including symptom-level eating disorder psychopathology (EDI-2 [30]) and general psychopathology (SCL-90-R [36]). We did not generate a priori hypotheses due to the exploratory nature of the study.

Materials and methods

Study samples

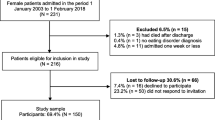

This was an exploratory, retrospective cohort study combining clinical data from the Eating Disorder Centre (EDC) at Aarhus University Hospital in the Central Denmark Region (CDR) with nationwide Danish register-based data. Patients were included if they a) had at least one outpatient contact or inpatient admission at the EDC between 2000 and the end of 2016 and b) had at least one inpatient admission with an AN diagnosis (aged at least 6 years at the time of diagnosis) at the EDC or another psychiatric hospital unit in the CDR in the same period. For patients with more than one admission with AN in the CDR the first one was used as the index admission. Four ICD-10 diagnostic codes—F50.0 (AN), F50.1 (atypical AN), F50.8 (other eating disorders), and F50.9 (unspecified eating disorders) [4]—were included using both primary and secondary diagnoses, because they are sometimes used for patients admitted without a prior thorough eating disorder assessment, but with suspected AN [12]. Because this was an exploratory study, we used sequential methodology, with two sets of inclusion and exclusion criteria, yielding two study samples. The first sample includes patients with a follow-up time of 2 years to explore factors associated with IT (yes/no), as a recent study shows that most IT happens within the first 2 years [12]. The second sample encompassed the first sample and extended it by allowing a varying (i.e., shorter) instead of a fixed follow-up time beginning at the index admission, thereby increasing the sample size and statistical power in the analyses of time to event. The difference between the two samples was predicated on this change in the follow-up time frame. Figure 1 illustrates the selection process. As we wanted to examine IT in connection to admissions for patients as young as age 6 and as the Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register started in 1969, we excluded patients born before 1963 (to ensure that patients were not older than 6 years in 1969). In this way, we avoided patients having an index admission before 1969 that would be unknown to us. Only patients who had at least one clinical eating disorder assessment at the EDC were included. For patients with more than one clinical eating disorder assessment within the study period, the first one was chosen. We excluded patients with an admission with AN before 2000, because the Registry of Coercive Measures in Psychiatric Treatment was either non-existent or incomplete in earlier years [55]. In the first study sample, patients with their first inpatient admission with an AN diagnosis in the CDR (the index admission) after 2014 were excluded to obtain a fixed 2-year follow-up period starting at the index admission. The second study sample differed only in that we retained patients with an index admission after 2014, thereby allowing for varying follow-up periods up to 2 years. In both samples, we further excluded patients who had their clinical eating disorder assessment later than 2 months into, or after, their index admission, expecting the scores to be stable within the first months. Moreover, patients who had their clinical eating disorder assessment more than 2 years before their index admission were excluded, thereby establishing a maximum time period of 2 years from assessment to hospitalization because of our interest in those factors associated with the risk of IT at treatment onset and to avoid a longer time span that might dilute any possible associations. Patients who emigrated, were lost to follow-up, or died were censored.

The study did not require ethical approval in Denmark. The study was registered with the Danish Patient Safety Authority, Danish Health Data Authority, and Danish Data Protection Agency. It conformed to the Helsinki Declaration [56] except regarding informed consent from patients. In accordance with Danish law, permission to access health record data was obtained from the Danish Patient Safety Authority and approval for using register-based data was obtained from the Danish Health Data Authority.

Data sources

We used the unique national Central Person Register number [57] to link the data. Health record data were collected from either the physical records at the Danish National Archives or the CDR's electronic health record systems and entered into an electronic database, REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) [58, 59], hosted at Aarhus University and the CDR's electronic research database, MidtX. Health record data from the different sources were then merged and kept in MidtX before being transferred to Statistics Denmark [60] and linked with data from the national Danish registers. The latter contained demographic data from the Danish Civil Registration System [57], treatment data from the Danish National Patient Register [61] and Danish Psychiatric Central Research Register [62], and IT data from the Registry of Coercive Measures in Psychiatric Treatment [12, 55].

Variables

Clinical data

Patients were identified by the Danish Health Data Authority. Clinical data from the health records of identified patients were retrieved by three clinical assistants and included data on the patients' BMI at index admission, residence (with family, alone, or at a specialized residence), and assessment of patient cooperation (good, neutral, or poor) as generally described at the pre-admission meeting and during the first week of admission. The latter categorical rating was made retrospectively based on a review of text in health records and entered into REDCap by the research assistant, and in case of doubt, group consensus was reached between the research assistants. Data from the clinical eating disorder assessments included self-reported age at onset, BMI at the time of the clinical eating disorder assessment, EDI-2 [30], and SCL-90-R [36] and were retrieved from health records by a clinical psychologist. The questionnaires were routinely conducted as part of a clinical eating disorder assessment at the beginning of the outpatient contact at the EDC. The EDI-2 measures eating disorder psychopathology, consists of 91 questions distributed across 11 scales [30], and has been validated in Denmark [63]. The SCL-90-R measures general psychopathology and consists of 90 questions distributed across nine scales [36]; it has also been validated in Denmark [64]. EDI-2 and SCL-90-R subscales were calculated according to their respective manuals [30, 36]. This included calculating subscales only if a required minimum of items were answered. If one or more subscales were not calculated due to too many missing items, the whole questionnaire was counted as missing. Hence, questionnaires were considered completed when results for all the subscales were available.

Register-based data

All admissions within the follow-up period were examined. We categorized IT events in the same way as Mac Donald et al. [12, p. 2], grouping IT measures into: "involuntary admission; detention; medication and electroconvulsive therapy; nasogastric tube feeding; IT for somatic illness; mechanical restraint including belt, straps and gloves; physical restraint; locked wards; constant observation; and sedative medication." These treatment types are all registered as IT by health care professionals in Denmark if used without consent. For instance, IT for somatic illness refers to treatment of physical conditions against a patient's wishes, such as administration of phosphate and potassium to avoid refeeding syndrome.

We also used the registers to extract information on sex, age at first AN diagnosis, age at index admission, previous admissions (yes/no) with other psychiatric disorders than AN, comorbidity at index admission (yes/no), and previous admissions (yes/no) with IT within 3 years before index admission. We limited the latter variable to 3 years to reduce the number of years with inconsistent or no collection of IT data.

Data analysis

For the first study sample, descriptive statistics, two-tailed t tests, Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney U tests, and chi-squared tests were used to compare patients with and without IT. For analyses with a fixed 2-year follow-up period, we used multivariate logistic regression to estimate the odds ratios for the outcome (IT) associated with an increase or decrease in our exposures, namely, eating disorder psychopathology (EDI-2 scales) and general psychopathology (SCL-90-R scales). Covariates other than the EDI-2 or SCL-90-R subscales were not used in the multivariate analyses to avoid reducing statistical power. The second study sample provided an increase in sample size and statistical power in the inferential statistical analyses. We again used descriptive statistics and tests to compare patients with and without IT. However, we did not conduct tests of significance for the variables that could be affected by the varying follow-up time such as the total number of admissions. Due to the varying follow-up periods, we used Cox regression analyses to estimate the associations, presented as hazard ratios, between our exposures and outcome. Our exposures were factors from the national Danish registers and health records including the scales of the EDI-2 and SCL-90-R, and our outcome was the time to the first IT event measured from 1 day before the index admission. We marked 1 day before the index admission as the starting date to include cases, where the index admission was involuntary (i.e., the starting date of the index admission and of the first IT event is the same). We conducted uni- and multivariate Cox regression analyses for EDI-2 and SCL-90-R scales, respectively. Again, the only covariates were the EDI-2 or the SCL-90-R subscales. For both study samples, the multivariate analyses of the EDI-2 and SCL-90-R were underpowered; however, we justified conducting them given the importance of identifying potential robust associations. Stata 16 software was used to manage and analyze the data [65]. Results for fewer than five individuals were omitted to ensure patient anonymity.

Results

Patient characteristics

The differences between the two samples were as follows. Two hundred and twelve patients were included in the first sample (see Table 1), whereas the second sample included an additional 66 patients (see Table 2). In the first sample, 56 had been treated involuntarily, 179 completed the full EDI-2, and 165 completed the full SCL-90-R with some subscales of both questionnaires having been answered by more patients. In the second sample, 72 had been treated involuntarily, 229 completed the full EDI-2, and 214 completed the full SCL-90-R, again with some patients answering only some subscales of the questionnaires. In the first sample, there were 186 patients with index admissions at the EDC and 26 patients with index admissions at other psychiatric units, whereas in the second sample, there were 252 patients with index admissions at the EDC and still 26 patients with index admissions at other psychiatric units. 55.4% of patients with IT in the first sample and 56.9% in the second sample had involuntary admission and/or detention as well as other IT measures. The outcome variables in the two samples were similar with patients being somewhat younger in the second sample.

Comparing patients in the first sample with (n = 56) and without IT (n = 156), the total number of admissions was the only variable that differed significantly, with the IT group having more admissions (p < 0.001) (see Table 1). Comparing patients with (n = 72) and without IT (n = 206) in the second sample, the level of patient cooperation differed significantly (see Table 2). Furthermore, the proportion of patients with IT within 3 years before index admission was higher among patients with IT than those without IT.

Clinical factors associated with IT

In the first sample, using multivariate logistic regression, increased scores on the subscale somatization were associated with increased odds of IT, whereas increased scores on the subscale phobic anxiety were associated with decreased odds of IT (see Table 3).

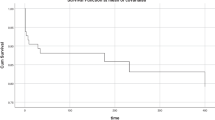

In the second sample, univariate Cox regression did not reveal any separate scale on the EDI-2 or SCL-90-R that was significantly associated with the time to IT (see Table 4). However, when the subscales were analyzed together within each questionnaire using multivariate Cox regression, increased somatization measured by the SCL-90-R was associated with decreased time to the first IT event (see Table 4).

In the second sample, univariate Cox regression revealed that previous admissions with IT within 3 years before index admission and neutral or poor patient cooperation were associated with decreased time to IT.

Discussion

Clinical factors associated with IT

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is one of the first to explore associations between either symptom-level eating disorder psychopathology or general psychopathology and IT. Broadly, we were unable to identify any eating disorder-specific variables associated with increased likelihood of IT or decreased time to IT. By contrast, elevated somatization general psychopathology scores were associated with increased likelihood of IT and decreased time to the first IT event at or after the index admission. Elevated phobic anxiety general psychopathology scores were associated with decreased likelihood of IT. Moreover, patient cooperation (as rated by clinical assistants) and previous admissions with IT were also associated with decreased time to IT.

We had hoped to find specific clinical symptom profiles that could alert clinicians to higher likelihood of requiring IT. To some extent we succeeded by identifying somatization and phobic anxiety. Somatization refers to complaints about somatic symptoms and could reflect subjective distress from physical discomfort or pain [36]. It has been associated with irritable bowel syndrome severity scores in patients with AN [66] and it improves with nutritional rehabilitation [67]. Patients with AN and high somatization have also been reported to show illness denial, demoralization, and alexithymia syndrome [68]. Overall, somatization seems to be a significant severity and distress marker in AN, also in connection to IT, that could alert clinicians of a greater risk of IT. With future research it may prove relevant to consider further interventions to prevent IT such as help with relieving or managing somatic symptoms. Phobic anxiety refers to specific fears such as the fear of crowds, buses, and places [36]. The association between phobic anxiety and the decreased likelihood of IT might be spurious, as it was only significant in the first sample. Alternatively, it may point to the possibility of feeling less exposed and vulnerable when admitted to a specialist ward and, therefore, safer and more willing and cooperative to work toward recovery.

We found that neutral patient cooperation and, especially, poor cooperation were associated with decreased time to the first IT event. This is not an unexpected result, because IT is commonly a consequence of dissent to treatment and it points to the importance of establishing patient–staff cooperation. However, overall, cooperation was low among patients with AN in this study with the majority of patients in both groups (with IT (86%) and without IT (64.1%)) judged to have neutral or poor cooperation with treatment by clinical assistants. With these high base rates of low cooperation, the clinical utility of recognizing poor cooperation as a harbinger of IT is low. Less cooperation has previously been found in involuntarily admitted patients with AN than in voluntarily admitted patients [69].

We also found that previous IT at admissions before the index admission decreased the time to the first IT event at or after the index admission. This confirms our previous result that "an IT event is often followed by other events" [12, p. 7]. General psychiatric research has shown that previous involuntary admissions are associated with increased risk of subsequent involuntary readmissions [70]. IT could breed IT, as suggested by Seed et al. [71], and we speculate that patient–staff dynamics such as staff expectations based on patient history could also play a role in recommending IT measures [72]. Furthermore, patients with previous IT may be a particularly unwell subgroup, who are more likely to require IT to ensure safety. However, few patients (n = 17) had a history of IT before their first admission with AN in the CDR and thus they only explain a minority of the IT cases.

Regarding eating disorder psychopathology, none of the odds ratios measured by the EDI-2 differed significantly between the groups. Although our comparisons were underpowered, the estimates were near unity with fairly small 95% confidence bands, suggesting that eating disorder psychopathology symptoms (as measured by the EDI-2) were not reliable factors associated with the risk of IT. Outliers of very high or very low scores were not analyzed separately, but may be of interest, as some patients with AN report low scores possibly due to illness denial [73] or because they feel better at low weights. Our result corresponds to Watson et al.'s [24] result of no difference between patients with and without involuntary admission when examining their EDI scores. BMI at clinical eating disorder assessment and BMI at index admission were also not associated with the time to IT. Patients with AN and IT have been shown to have a lower BMI at admission than voluntarily treated patients [13, 74], but the difference is generally small and not clinically meaningful [15]. Furthermore, neither previous admissions with psychiatric disorders other than AN nor comorbidity at index admission differed significantly between the IT and no IT groups. We cannot rule out the importance of any specific previous psychiatric disorders affecting the time to IT, because there were too few patients to conduct the analyses. However, previous admissions with diagnoses other than AN, including schizophrenia spectrum disorders, autism spectrum disorders, and personality disorders, have been found to be associated with subsequent IT in register-based studies [11, 12]. A study showed more personality disorders in involuntarily admitted patients than voluntarily admitted patients [69]. Moreover, depression has been associated with IT in AN [10, 15].

We found that more than half of the patients with IT had involuntary admission and/or detention as well as other IT measures. This supports that involuntary admission can to some extent be considered a proxy for other IT measures [12, 18]. In fact, Danish law requires that the conditions for involuntary admission are met for other IT measures to be initiated [23].

Strengths and limitations

The present study has the strength of combining health record data with data from the national Danish registers, making it possible to examine all inpatient admissions in Denmark following a clinical eating disorder assessment at the EDC and index admission in the CDR. Moreover, using the Danish registers to identify patients, as done by the Danish Health Data Authority, and admissions maximized the detection of IT, while minimizing recall and selection bias.

There are limitations to our study. Despite employing a sample of 278 patients, the study was underpowered and we did not correct for multiple comparisons; therefore, the risk of type I or II errors is increased and the results should be interpreted with caution. For patients with an index admission in 2000, the variable previous admissions with IT within 3 years before index admission covered the years in which the Registry of Coercive Measures in Psychiatric Treatment [55] either did not yet exist or was inconsistently used. We included the diagnoses of other eating disorders (F50.8) and unspecified eating disorders (F50.9), thereby making the patient group studied more diverse. However, these diagnoses are sometimes used for patients admitted without a prior thorough eating disorder assessment, but with suspected AN [12], and post hoc analysis showed that only 5.4% of the patients in the second sample did not have a lifetime F50.0 or F50.1 diagnosis in relation to a hospital contact (outpatient or inpatient) before the end of follow-up.

We conducted our time-to-event analyses under the assumption that the clinical symptoms measured by the questionnaires were stable up to 2 months into the index admission. Although studies have found high test–retest reliability over a week for both the EDI-2 and the SCL-90-R [75, 76], this may not be the case over a longer period. However, post hoc analyses showed that less than 3% in both samples had their clinical eating disorder assessment more than a week into the index admission. Furthermore, the varying time between clinical eating disorder assessments and index admissions may have influenced the non-predictive results for the EDI-2 and SCL-90-R questionnaires. Moreover, the quality of clinical assistants' assessments of patient cooperation may have varied. We ensured that clinical assistants had bachelor's degrees in psychology, had an overall introduction to the content of the health records, and focused on patient cooperation, as described in the pre-admission meeting and within the first week of admission. Assistants collaborated and discussed unclear cases when needed.

The Danish registers do not provide information on which diagnosis is associated with an IT event. In cases with comorbid disorders, whether IT was related to AN (with the exception of nasogastric tube feeding) is unknown. Furthermore, the present study was based on a sample of patients with a clinical eating disorder assessment at the EDC and index admission in the CDR, which may limit its external validity. This should be considered when generalizing to other treatment facilities or countries [77] with different practices. For example, a physician in Denmark who has been alerted can propose IT, after which it is validated by a chief physician; a judge is only involved if a patient appeals a complaint [22, 23]. In addition, registration of IT is not systematic in many countries outside of Scandinavia. Thus, it is difficult to compare the use of IT across European and other non-European countries, where variation in legislation [22] likely also contributes to differences in the use of IT. The use of IT is generally comparable in Scandinavian countries, with some variation in the use of specific IT measures [77]. Finally, a number of patients were excluded due to having no clinical eating disorder assessment at the EDC. Patients directly admitted to inpatient treatment without a prior outpatient contact may not have participated in a clinical eating disorder assessment, including the EDI-2 and the SCL-90-R.

Conclusions

In this study, we used sequential methodology yielding two study samples (one encompassing and extending the other), because the literature on IT in AN is still sparse and we hoped to maximize the information gleaned by taking this exploratory approach. Overall, we did not identify a particular eating disorder profile from the EDI-2 that captured the risk of receiving IT. Notably, this suggests that the EDI-2 dimensions associated with illness course and treatment challenges [25, 31, 32] differ from those that influenced the likelihood of receiving IT or time to the first IT event. In terms of general psychopathology, only somatization on the SCL-90-R, which has been associated with more severe symptoms in AN, was positively associated with both likelihood of IT and time to IT, whereas phobic anxiety was negatively associated with the likelihood of IT.

Our findings of poor patient cooperation and previous IT being associated with shorter time until IT raise important clinical issues that need to be addressed using a more in-depth methodology. Patients' non-cooperation is subjective and decisions to use IT may in part be influenced by clinicians’ awareness of the historical use of IT with any given patient. Knowing that a patient underwent IT in the past may increase the likelihood of clinical staff recommending its use again and may also influence ratings of cooperation. Although historical clinical information is extremely valuable for treatment planning, clinicians should be open to the possibility of patients changing over time in both their level of cooperation and their need for IT. Ensuring unbiased evaluation upon readmission could help break the cycle of repeat readmissions marked by IT. Novel approaches to acute AN care such as self-admission [78, 79] and home-based care [80, 81] that have the potential to increase patient and family agency in recovery could mitigate the cycle of repeat admissions with IT that may contribute to demoralization of patients, family members, and clinicians. The fact that the number of associations between clinical factors and IT found in our study was limited points to the importance of extending future research to examine treatment contexts more broadly.

What is already known on this subject?

Improving the ability of clinicians to identify patients at risk of involuntary treatment (IT) is important to intervene and prevent future IT. Clinical factors including eating disorder psychopathology and more general psychopathology have been identified as severity markers increasing the risk of a severe illness course and treatment challenges in anorexia nervosa (AN), but have not been tested in relation to IT. The literature on psychopathology symptoms associated with IT is sparse and symptom-level markers of IT still require exploration.

What does this study add?

We explored associations between clinical factors and IT. This is one of the first studies to explore associations between either symptom-level eating disorder psychopathology or general psychopathology and IT. Somatization and phobic anxiety as measured by the SCL-90-R were positively and negatively, respectively, associated with the likelihood of IT. Somatization, previous admissions with IT, and neutral or poor patient cooperation were associated with decreased time to the first IT event. Eating disorder psychopathology measured by the EDI-2 was not significantly associated with likelihood of IT or time to the first IT event.

Data availability

The data from health records and the Danish national registers are not publicly available. Stata 16 code from Statistics Denmark’s servers is not publicly available.

References

Roncero M, Belloch A, Perpiñá C, Treasure J (2013) Ego-syntonicity and ego-dystonicity of eating-related intrusive thoughts in patients with eating disorders. Psychiatry Res 208:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2013.01.006

Gregertsen EC, Mandy W, Serpell L (2017) The egosyntonic nature of anorexia: an impediment to recovery in anorexia nervosa treatment. Front Psychol 8:2273. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02273

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z (2014) Eating disorders: a transdiagnostic protocol. In: Barlow DH (ed) Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: a step-by-step treatment manual, 5th edn. Guilford, NY, pp 670–702

World Health Organization (1992) The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. WHO, Geneva

Forrest LN, Smith AR, Swanson SA (2017) Characteristics of seeking treatment among US adolescents with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 50(7):826–833. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22702

Wallier J, Vibert S, Berthoz S, Huas C, Hubert T, Godart N (2009) Dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: critical review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord 42(7):636–647. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20609

Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba E, Abbate-Daga G (2009) Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BioMed Central Psychiatry 9(1):67. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-67

Khalsa SS, Portnoff LC, McCurdy-McKinnon D, Feusner JD (2017) What happens after treatment? A systematic review of relapse, remission, and recovery in anorexia nervosa. J Eat Disord 5:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-017-0145-3

Clausen L, Jones A (2014) A systematic review of the frequency, duration, type and effect of involuntary treatment for people with anorexia nervosa, and an analysis of patient characteristics. J Eat Disord 2:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-014-0029-8

Elzakkers IFFM, Danner UN, Hoek HW, Schmidt U, van Elburg AA (2014) Compulsory treatment in anorexia nervosa: a review. Int J Eat Disord 47:845–852. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22330

Clausen L, Larsen JT, Bulik CM, Petersen L (2018) A Danish register-based study on involuntary treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 51:1213–1222. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22968

Mac Donald B, Bulik CM, Larsen JT, Carlsen AH, Clausen L, Petersen LV (2021) Involuntary treatment in patients with anorexia nervosa: utilization patterns and associated factors. Psychol Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172100372X

Halvorsen I, Tollefsen H, Rø Ø (2016) Rates of weight gain during specialised inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa. Adv Eat Disord 4(2):156–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/21662630.2016.1138413

Griffiths RA, Beumont PJ, Russell J, Touyz SW, Moore G (1997) The use of guardianship legislation for anorexia nervosa: a report of 15 cases. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 31:525–531. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048679709065074

Atti AR, Mastellari T, Valente S, Speciani M, Panariello F, De Ronchi D (2021) Compulsory treatments in eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Weight Disord 26(4):1037–1048. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01031-1

Ayton A, Keen C, Lask B (2009) Pros and cons of using the Mental Health act for severe eating disorders in adolescents. Eur Eat Disord Rev: J Eat Disord Assoc 17:14–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.887

Di Lodovico L, Duquesnoy M, Dicembre M, Ringuenet D, Godart N, Gorwood P et al (2021) What distinguish patients with compulsory treatment for severely undernourished anorexia nervosa. Eur Eat Disord Rev 29(1):144–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2790

Sashidharan SP, Mezzina R, Puras D (2019) Reducing coercion in mental healthcare. Epidemiol Psychiat Sci 28(6):605–612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000350

Halmi KA (2018) Psychological comorbidities of eating disorders. In: Agras SW, Robinson A (eds) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 229–243

Keel PK (2018) Epidemiology and course of eating disorders. In: Agras SW, Robinson A (eds) The Oxford handbook of eating disorders, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 34–43

Touyz SW, Carney T (2010) Compulsory (involuntary) treatment for anorexia nervosa. In: Grilo CM, Mitchell JE (eds) The treatment of eating disorders: a clinical handbook BT. Guilford Press, New York, NY, pp 212–224

Saya A, Brugnoli C, Piazzi G, Liberato D, Di Ciaccia G, Niolu C et al (2019) Criteria, procedures, and future prospects of involuntary treatment in psychiatry around the world: a narrative review. Front Psychiatry 10:271. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00271

Sundheds- og Ældreministeriet [The Danish Ministry of Health and Senior Citizens] (2019). Bekendtgørelse af lov om anvendelse af tvang i psykiatrien m.v. [Promulgation of the law on the use of coercion in psychiatry, etc.].

Watson TL, Bowers WA, Andersen AE (2000) Involuntary treatment of eating disorders. Am J Psychiatry 157:1806–1810. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.11.1806

Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Crosby RD, Koch S (2017) Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa: results from a large clinical longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord 50(9):1018–1030. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22736

Steinhausen H-C (2002) The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry 159:1284–1293. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284

Støving RK, Andries A, Brixen KT, Bilenberg N, Lichtenstein MB, Hørder K (2012) Purging behavior in anorexia nervosa and eating disorder not otherwise specified: a retrospective cohort study. Psychiatry Res 198(2):253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.009

Franko DL, Tabri N, Keshaviah A, Murray HB, Herzog DB, Thomas JJ et al (2018) Predictors of long-term recovery in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: data from a 22-year longitudinal study. J Psychiatr Res 96:183–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.10.008

Vall E, Wade TD (2015) Predictors of treatment outcome in individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 48(7):946–971. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22411

Garner DM (1991). EDI-2 Eating disorder inventory-2. Professional manual: PAR Psychological assessment resources, Inc.

Zeeck A, Hartmann A, Buchholz C, Herzog T (2005) Drop outs from in-patient treatment of anorexia nervosa. Acta Psychiatr Scand 111(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2004.00378.x

Kästner D, Löwe B, Weigel A, Osen B, Voderholzer U, Gumz A (2018) Factors influencing the length of hospital stay of patients with anorexia nervosa – results of a prospective multi-center study. BMC Health Serv Res 18:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2800-4

Schlegl S, Diedrich A, Neumayr C, Fumi M, Naab S, Voderholzer U (2016) Inpatient treatment for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: clinical significance and predictors of treatment outcome. Eur Eat Disord Rev 24(3):214–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2416

Tan J, Hope T, Stewart A (2003) Competence to refuse treatment in anorexia nervosa. Int J Law Psychiatry 26:697–707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2003.09.010

Papadopoulos FC, Ekbom A, Brandt L, Ekselius L (2009) Excess mortality, causes of death and prognostic factors in anorexia nervosa. Br J Psychiatry 194(1):10–17. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054742

Derogatis LR (1992). SCL-90-R®. Administration, scoring and procedures manual-II. Towson, MD: Clinical Psychometric Research, Inc.

Huas C, Godart N, Foulon C, Pham-Scottez A, Divac S, Fedorowicz V et al (2011) Predictors of dropout from inpatient treatment for anorexia nervosa: data from a large French sample. Psychiatry Res 185(3):421–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2009.12.004

Sansfaçon J, Booij L, Gauvin L, Fletcher É, Islam F, Israël M et al (2020) Pretreatment motivation and therapy outcomes in eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord 53(12):1879–1900. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23376

Zaitsoff S, Pullmer R, Cyr M, Aime H (2015) The role of the therapeutic alliance in eating disorder treatment outcomes: a systematic review. Eat Disord 23(2):99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2014.964623

Akther SF, Molyneaux E, Stuart R, Johnson S, Simpson A, Oram S (2019) Patients’ experiences of assessment and detention under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Br J Psychiatry Open 5:e37. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.19

Krieger E, Moritz S, Lincoln TM, Fischer R, Nagel M (2020) Coercion in psychiatry: a cross-sectional study on staff views and emotions. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12643

Tingleff EB, Bradley SK, Gildberg FA, Munksgaard G, Hounsgaard L (2017) “Treat me with respect”. A systematic review and thematic analysis of psychiatric patients’ reported perceptions of the situations associated with the process of coercion. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 24:681–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12410

Seed T, Fox JRE, Berry K (2016) The experience of involuntary detention in acute psychiatric care. A review and synthesis of qualitative studies. Int J Nurs Stud 61:82–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.05.014

Jankovic J, Yeeles K, Katsakou C, Amos T, Morriss R, Rose D et al (2011) Family caregivers’ experiences of involuntary psychiatric hospital admissions of their relatives—a qualitative study. PLoS ONE 6(10):e25425. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0025425

Prinsen EJD, van Delden JJM (2009) Can we justify eliminating coercive measures in psychiatry? J Med Ethics 35:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2007.022780

Silber TJ (2011) Treatment of anorexia nervosa against the patient’s will: ethical considerations. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 22:283–288

Finansministeriet [Ministry of Finance] (2013). Aftaler om finansloven for 2014 [Agreements on the Finance Act for 2014]. Albertslund: Rosendahls-Schultz Grafisk.

Gooding P, McSherry B, Roper C (2020) Preventing and reducing “coercion” in mental health services: an international scoping review of English-language studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand 142(1):27–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13152

National Mental Health Commission (2012) A contributing life, the 2012 national report card on mental health and suicide prevention. NMHC, Sydney.

Puras D (2017). Report of the special rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health. UN general assembly A/HRC/35/21.

DeLacy L, Edner B, Hart C, McCann K, Szpak C, Johnson B (2003). Learning from each other: Success stories and ideas for reducing restraint/seclusion in behavioral health. American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Nurses Association, National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems.

Walker S, Barnett P, Srinivasan R, Abrol E, Johnson S (2021) Clinical and social factors associated with involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation in children and adolescents: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 5(7):501–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00089-4

Walker S, Mackay E, Barnett P, Sheridan Rains L, Leverton M, Dalton-Locke C et al (2019) Clinical and social factors associated with increased risk for involuntary psychiatric hospitalisation: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and narrative synthesis. Lancet Psychiatry 6(12):1039–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30406-7

Luciano M, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Pingani L, Palumbo C, De Rosa C et al (2014) Use of coercive measures in mental health practice and its impact on outcome: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother 14(2):131–141. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2014.874286

Sundhedsdatastyrelsen [The Danish Health Data Authority] (2020). Register over anvendelse af tvang i psykiatrien [Register on the use of coercion in psychiatry] [Available from: https://www.esundhed.dk/Dokumentation/DocumentationExtended?id=27.

World Medical Association (2013) World medical association declaration of Helsinki. JAMA 310:2191–2194. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281053

Pedersen CB (2011) The Danish civil registration system. Scand J Public Health 39(7 Suppl):22–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810387965

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L et al (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 42(2):377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Statistics Denmark (2020). Danmarks Statistik [Available from: https://www.dst.dk/da/].

Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M (2011) The Danish national patient register. Scand J Public Health 39(7_suppl):30–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494811401482

Mors O, Perto GP, Mortensen PB (2011) The Danish psychiatric central research register. Scand J Public Health 39:54–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810395825

Clausen L, Rokkedal K, Rosenvinge JH (2009) Validating the eating disorder inventory (EDI-2) in two danish samples: a comparison between female eating disorder patients and females from the general population. Eur Eat Disord Rev 17(6):462–467. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.945

Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P (2006) Mental distress in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 113(6):477–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00743.x

Statacorp (2019) Stata statistical software: release 16. StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX

Kessler U, Rekkedal GÅ, Rø Ø, Berentsen B, Steinsvik EK, Lied GA et al (2020) Association between gastrointestinal complaints and psychopathology in patients with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 53(5):802–806. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23243

Perez ME, Coley B, Crandall W, Di Lorenzo C, Bravender T (2013) Effect of nutritional rehabilitation on gastric motility and somatization in adolescents with anorexia. J Pediatr 163(3):867–72.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.011

Abbate-Daga G, Delsedime N, Nicotra B, Giovannone C, Marzola E, Amianto F et al (2013) Psychosomatic syndromes and anorexia nervosa. BMC Psychiatry 13(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-14

Zohar-Beja A, Latzer Y, Adatto R, Gur E (2015) Compulsory treatment for anorexia nervosa in Israel: clinical outcomes and compliance. Int J Clin Psychiatry Ment Health 3:20–30

Lay B, Kawohl W, Rössler W (2019) Predictors of compulsory re-admission to psychiatric inpatient care. Front Psych 10:120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00120

Seed T, Fox J, Berry K (2016) Experiences of detention under the mental health act for adults with anorexia nervosa. Clin Psychol Psychother 23(4):352–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1963

Perkins E, Prosser H, Riley D, Whittington R (2012) Physical restraint in a therapeutic setting; a necessary evil? Int J Law Psychiatry 35(1):43–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.11.008

Nevonen L, Broberg AG (2001) Validating the eating disorder inventory-2 (EDI-2) in Sweden. Eat Weight Disord - Stud Anorex, Bulim Obes 6(2):59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03339754

Carney T, Wakefield A, Tait D, Touyz S (2006) Reflections on coercion in the treatment of severe anorexia nervosa. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci 43(3):159–165

Thiel A, Paul T (2006) Test–retest reliability of the eating disorder inventory 2. J Psychosom Res 61(4):567–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.02.015

Tomioka M, Shimura M, Hidaka M, Kubo C (2008) The reliability and validity of a Japanese version of symptom checklist 90 revised. Biopsychosoc Med 2(1):19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-2-19

Bak J, Aggernæs H (2012) Coercion within Danish psychiatry compared with 10 other European countries. Nord J Psychiatry 66(5):297–302. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.632645

Strand M, Bulik CM, von Hausswolff-Juhlin Y, Gustafsson SA (2017) Self-admission to inpatient treatment for patients with anorexia nervosa: the patient’s perspective. Int J Eat Disord 50(4):398–405. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22659

Strand M, Bulik CM, Gustafsson SA, von Hausswolff-Juhlin Y, Welch E (2020) Self-admission to inpatient treatment in anorexia nervosa: Impact on healthcare utilization, eating disorder morbidity, and quality of life. Int J Eat Disord 53(10):1685–1695. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23346

Bosanac P, Newton R, Harari E, Castle D (2010) Mind the evidence gap: do we have any idea about how to integrate the treatment of anorexia nervosa into the Australian mental health context? Australas Psychiatry 18(6):517–522. https://doi.org/10.3109/10398562.2010.499433

Latzer Y, Herman E, Ashkenazi R, Atias O, Laufer S, Biran Ovadia A et al (2021) Virtual online home-based treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic for ultra-orthodox young women with eating disorders. Front Psychiatry 12:654589. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.654589

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dr. Janne T. Larsen for her support with data management and Mr. Anders H. Carlsen for his support with data management and analyses.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Dr. Bulik, grant numbers R01MH120170; R01MH124871; R01MH119084; R01MH118278; R01 MH124871); Brain and Behavior Research Foundation Distinguished Investigator Grant (Dr. Bulik); Swedish Research Council Vetenskapsrådet (Dr. Bulik, award 538-2013-8864); the National Institutes of Health (Drs. Bulik and Petersen, grant number R01MH120170); Lundbeckfonden (Drs. Petersen and Bulik, grant number R276-2018-4581); Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, Aarhus University Hospital (Mr. Mac Donald, internal funding without a grant number); and Fru C. Hermansens Mindelegat (Mr. Mac Donald, no grant number available). The funders had no involvement in any aspect of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BMD was involved in the initial idea of the study, the study design, data management, data analysis, interpretation of results, and was responsible for writing the paper. LVP, CMB, and LC were involved in the study design, interpretation of results, and paper revision. LVP and LC also supervised data analysis. All authors approved the final version of the paper. LVP and LC contributed equally to the study and share senior authorship.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Bulik reports: Takeda (grant recipient, scientific advisory board); Idorsia (consultant); Pearson (author, royalty recipient); Equip Health Inc. (clinical advisory board). Mr. Mac Donald and Drs. Petersen and Clausen have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical approval

The study did not require approval by an ethics committee in Denmark. In accordance with Danish law, permission to access health record data was obtained from the Danish Patient Safety Authority (3–3013-2627/1) and approval for using register-based data was obtained from the Danish Health Data Authority (FSEID-00004078; FSEID-00001107). The study conformed to the Helsinki Declaration except regarding informed consent from patients.

Consent to participate

The data were obtained from health records and the Danish national registers. In accordance with Danish law, permission to access health record data was obtained from the Danish Patient Safety Authority (3–3013-2627/1) and approval for using register-based data was obtained from the Danish Health Data Authority (FSEID-00004078; FSEID-00001107).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mac Donald, B., Bulik, C.M., Petersen, L.V. et al. Influence of eating disorder psychopathology and general psychopathology on the risk of involuntary treatment in anorexia nervosa. Eat Weight Disord 27, 3157–3172 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01446-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01446-y