Abstract

Purpose

Emotion regulation (ER) refers to the processes by which individuals influence the onset, intensity, and duration of emotions. Previous studies have examined the effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER in isolation, but growing evidence suggests that they should be studied in conjunction. This study examined the interactions between habitual adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies with eating disorder (ED) symptoms and ED-related clinical impairment.

Methods

Students (N = 1377) from a Midwestern American university reported ED symptoms, ED-related impairment, habitual adaptive ER (i.e., cognitive reappraisal), and habitual maladaptive ER (i.e., distraction and suppression). Multiple linear regressions were conducted using the PROCESS v3 macro.

Results

The study found that adaptive ER was negatively associated with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment, whereas maladaptive ER was positively associated with both outcome variables. Adaptive ER moderated the association between maladaptive ER and ED symptoms, but not clinical impairment. When habitual adaptive ER was low (< 33.4th percentile), there was no association between maladaptive ER and ED symptoms; however, when habitual adaptive ER was moderate to high (> 33.4th percentile), there was a positive association between frequency of maladaptive ER use and ED symptoms. There was no significant three-way interaction among adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis, for ED-related impairment or symptoms.

Conclusion

Results suggest that irrespective of frequency of maladaptive ER, people with low adaptive ER reported elevated psychopathology. Findings point to the utility of interventions to reduce maladaptive ER and increase adaptive ER in ED populations.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Emotion regulation (ER) strategies are the processes by which individuals influence onset, duration, and intensity of emotions [1]. Previous research has typically examined individual associations between the habitual use of either “adaptive” or “maladaptive ER” strategies and mental-health outcomes [2,3,4]. In general, ER strategies with negative relationships with psychopathology (i.e., greater use of the strategy corresponds to fewer symptoms), such as cognitive reappraisal, problem-solving, and acceptance, have been conceptualized as adaptive [3]. ER strategies with positive relationships with psychopathology (i.e., greater use of the strategy corresponds to more symptoms), such as avoidance, rumination, and suppression, have been referred to as maladaptive [3]. Overall, these distinctions between adaptive and maladaptive strategies have been replicated when predicting a variety of mental health conditions, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, eating, substance-use, and borderline personality disorders (e.g., [1, 2, 5,6,7]), leading many to characterize ER as a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology. It is important to note, however, that strategies are not universally “adaptive” or “maladaptive” [8] and that the adaptiveness of strategies should be evaluated within their context, which includes short-term and long-term outcomes, instrumental goals, and social and behavioral consequences (see [9, 10]).

The interaction between adaptive and maladaptive strategies

However, emerging research suggests that studying adaptive ER and maladaptive ER strategies as independent predictors does not provide an adequate representation of how ER use affects one’s well-being. This is because most people do not exclusively use one strategy to manage emotions; instead, they draw upon a set of available strategies (repertoire) of both adaptive ER and maladaptive ER [2, 11]. Thus, to characterize the nature of how adaptive and maladaptive strategies are associated with psychopathology, one must examine the interactions between these two types of strategies. Consequently, two hypotheses have been put forward to evaluate interactions between strategy types—the compensatory hypothesis and the interference hypothesis [2].

The compensatory hypothesis assumes that an individual flexibly uses a set of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER strategies, depending on the contexts. More specifically, adaptive ER “compensates” for the maladaptive ER included in one’s repertoire. This explains why adaptive ER tends to have a stronger negative relationship with symptoms of psychopathology for people who also report high levels of maladaptive ER, rather than those who report low levels of maladaptive ER [2]. By contrast, the interference hypothesis states that maladaptive ER “interferes” and prevents one from benefiting from adaptive ER [2]. This hypothesis posits that adaptive ER is only associated with psychopathology when the use of maladaptive ER is low.

These hypotheses can also be tested by evaluating adaptive ER as a moderator of the association between maladaptive ER and psychopathology. Using adaptive ER as the moderator, instead of looking at maladaptive ER as the moderator allows us to shed new light on the potential role of incorporating adaptive ER strategy in treatment and prevention efforts, in conjunction with reducing one’s use of maladaptive ER. It may be more clinically important to understand when adaptive ER modifies the influence of maladaptive ER on psychopathology. Previous research that focused on the moderating role of adaptive ER examined the interactions between the two types of ER and their association with psychopathology in an interpersonal context [12] and with the psychophysiological measurement of resting-state respiratory sinus arrhythmia [11]. Both studies found a moderating effect of adaptive ER in the association between maladaptive ER and psychopathology [12], as well as the association with physiological functioning [11]. Evaluating the interaction between adaptive and maladaptive ER is important for understanding for whom maladaptive ER strategies lead to greater psychopathology symptoms. In this context, the compensatory hypothesis suggests that the association between maladaptive ER and psychopathology is stronger when adaptive ER is high, whereas the interference hypothesis implies that the association is stronger when adaptive ER is low.

Clinical case status as a contextual factor

Research suggests that which hypothesis (interference or compensatory) is supported depends on the severity of psychopathology in the sample; in other words, whether members of the sample are less or more symptomatic may serve as a moderator of the relationship (three-way interaction among adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis). In general, the compensatory effect tends to be observed among less symptomatic individuals [2, 4, 11], whereas the interference effect is usually found among highly symptomatic individuals [13,14,15].

In past studies, researchers have examined the interactions among symptoms of mental disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder [2, 4, 13,14,15]; however, eating disorders (ED) have yet to be adequately studied with regard to interactions between ER strategies. At present, although there is meta-analytic evidence to support the associations between adaptive and maladaptive strategies and ED symptoms [6], there has yet to be a study that has tested interactions among ER strategies in this population. Understanding interactions among ER strategies is important because examining how strategies function together is a more ecologically valid representation of ER in people with psychopathology than studying strategies as individual predictors. Understanding combinations of strategies may also guide clinical decision making, because it could support the implementation of interventions that seek to increase adaptive strategies and/or decrease maladaptive strategies and provide a shift to more person-centered approaches to implementing ER [16].

For this study, we chose to use reappraisal as the adaptive ER strategy, as it is a commonly utilized skill taught in cognitive-behavioral therapy and has been used as an adaptive strategy in previous studies (e.g., [11, 13, 14]). We used a measure that assessed distraction and suppression for maladaptive ER, as suppression has been linked to elevated psychopathology [3, 6] and distraction is implicated in current models of the maintenance of ED pathology [17,18,19]. Specifically, when distraction is used frequently over time, it is believed to reinforce the avoidance of negative emotions or feared situations (e.g., food), which inhibits adaptive learning processes that may be necessary for recovery from an ED [17,18,19]. Consequently, although distraction may be effective in the short term to decrease intense level of emotional distress [20, 21], it is less effective for long-term adjustment [22, 23].

In this study, the main objective was to examine whether adaptive ER would moderate the association between (1) maladaptive ER and ED symptoms and (2) maladaptive ER and ED-related clinical impairment. We examined ED-related impairment in addition to ED symptoms to provide additional contextual information about how ER may impact functioning. ED-related impairment reliably and validly measures one’s psychosocial impairment secondary to ED symptoms, encompassing three domains such as personal, cognitive, and social, whereas the ED symptom score is more heavily driven by frequency of behaviors. Consequently, symptom endorsement and impairment are separate constructs. We tested a three-way interaction to determine if the maladaptive-adaptive ER interaction varied by probable ED diagnosis status, given the support for the interference hypothesis and the compensatory hypothesis in clinical and non-clinical samples, respectively.

Hypotheses

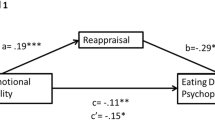

H1: three-way interaction with lower order interactions and conditional effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

We hypothesized that there would be a significant three-way interaction among adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis (i.e., clinical case status) for ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. If the three-way interaction was significant, the pattern of the two-way interaction between maladaptive and adaptive ER would depend on clinical case status, such that participants with probable ED would show maladaptive × adaptive ER interactions consistent with the interference hypothesis and participants without probable ED would show maladaptive × adaptive ER interactions consistent with the compensatory hypothesis (Fig. 1).

H2: two-way interaction with conditional effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

There would be a significant two-way interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. Given that this was an unselected sample (i.e., not selected based on pre-existing clinical characteristics), we predicted that if the three-way interaction was not significant, this sample would show a maladaptive × adaptive ER interaction consistent with the compensatory hypothesis.

H3: main effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

There would be significant main effects of ER (adaptive or maladaptive) on psychopathology. In other words, consistent with prior meta-analyses of ER strategies as individual predictors [3, 6], we predicted that adaptive ER would be negatively associated with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment, whereas maladaptive ER would be positively associated with both outcome variables.

Methods

Participants

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected from a screening of ED behaviors among undergraduate and graduate students from the University of Kansas. Participants were current students from the University of Kansas aged ≥ 18 years who completed a survey assessing eating and body weight concerns (N = 1377; Mage = 23.61, SD = 7.15, range 18–76). A total of 1994 responses were received. After removing invalid responses (refer to “Statistical analysis” for more details), the final analytic sample included 1377 responses. Demographic characteristics of the final analytic sample are summarized in Table 1.

Measures

Habitual ER questionnaires

Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) [24]

The ERQ is a 10-item questionnaire measuring one’s tendency in ER strategy use. Each item is answered on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”). Only the six-item Cognitive Reappraisal subscale assessing an individual’s use of reappraisal in regulating emotion was collected, including items such as “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in.” In our sample, the Cognitive Reappraisal subscale demonstrated good internal consistency (α = 0.89).

Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire (MEAQ) [25]

The MEAQ is a 62-item self-report questionnaire which assesses experiential avoidance, rated from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 6 (“Strongly agree”). In the present study, only the 7-item Distraction/Suppression subscale was collected (e.g., “When something upsetting comes up, I try very hard to stop thinking about it”). In our sample, the Distraction/Suppression subscale showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91).

Eating psychopathology questionnaires

Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale 5 (EDDS) [26]

The EDDS is 22-item self-report measure that assesses eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and other specified feeding and eating disorders, according to DSM-5 criteria [27]. The EDDS assesses cognitive and behavioral symptoms of DSM-5 EDs, as well as impairment, over the past three months. For frequencies of ED behaviors (binge eating, restriction, self-induced vomiting, laxative/diuretic use, compensatory exercise), participants indicate the average number of episodes per month over the past three-months. The EDDS demonstrated great internal consistency (α = 0.89) and test–retest reliability (r = 0.87) [28]. In this study, the night-eating question was removed, and an ad hoc question regarding subjective binge eating was included with permission from the copyright holder (“How many times per month on average over the past 3 months did you feel that your eating was out of control (that you could not stop once you started) after eating a SMALL or NORMAL amount of food (e.g., after eating a few standard-size cookies or a standard-size meal)?”). We calculated the composite severity score by summing all items, but caution that our symptom score should not be compared directly to other studies using EDDS composite scores or norms, given the exclusion of the night-eating question and addition of the subjective binge-eating question. The EDDS provided information about the frequency of ED-related behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting, compensatory fasting, objective binge eating) that were used to establish probable ED diagnosis (see “Probable eating disorder diagnosis”).

The Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA) [29]

The CIA is a self-report measure that consists of 16 items, rated from 0 (“Not at all”) to 3 (“A lot”). This measure assesses the impact of ED psychopathology on one’s psychosocial functioning. A CIA global score is the sum of scores on all items (ranging from 0 to 48), with higher CIA global score demonstrating greater severity of clinical impairment related to ED psychopathology. This measure shows good psychometric properties, including high levels of internal consistency, construct validity, test–retest reliability, sensitivity to change, and discriminant validity in clinical and non-clinical trials [29, 30]. A cutoff score of 16 showed excellent sensitivity and specificity to detect clinical impairment due to ED psychopathology [30]. The internal consistency of the CIA in this sample was excellent (α = 0.95).

Probable eating disorder diagnosis

Combining information from the EDDS and CIA measures (see also procedure in [31]), we categorized participants as having probable anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge-eating disorder (BED), other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED), or no ED diagnosis. Individuals who met full criteria for AN, BN, and BED according to behavioral frequencies using the EDDS and had a score of greater than or equal to 16 on CIA were classified as having a probable ED diagnosis in the respective categories. Individuals who reported significant ED behaviors not meeting full frequency criteria for AN, BN, or BED and had a CIA global score greater or equal to 16 were classified as having a probable ED diagnosis under the OSFED group. Students who did not have significant ED behaviors nor significant ED-related impairment were classified as having no ED diagnosis.

Procedure

All the procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board. Participants were recruited through mass emails that were sent to approximately 18,000 undergraduate and graduate students at the University of Kansas (KU) on September 14th, 2020. Participants were informed that the purpose of the study was to evaluate eating concerns and body- or weight-related issues among KU students and were encouraged to complete the survey, even if they did not think they had eating-related problems. Participants were required to provide informed consent prior to completing the survey using the REDCap database system.

Statistical analysis

To ensure data quality, we took several steps for data cleaning. We wrote SPSS syntax to identify and flag potential invalid responses for removal. We removed 617 responses from the final analytic sample due to reasons such as invalid BMI (e.g., BMI of 0.30), missing critical values on the EDDS, ERQ, and MEAQ, duplicate responses, and medical exclusion criteria from the parent screening study (e.g., pregnant or breastfeeding). After data cleaning, we carried out additional analyses to ensure that statistical assumptions were met; this included removing extreme outliers (3 SD above or below mean), performing natural log transformation on skewed and kurtotic variables; and mean-centering the predictor.

For our statistical analysis, we used the PROCESS v3 macro for SPSS v27 [32]. For all analyses, lower level interactions and conditional effects were included in the models, as appropriate. First, we tested the three-way interaction between adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment using PROCESS Model 3. If this interaction was significant, we planned to divide the sample into two groups based on their clinical case status (i.e., probable ED diagnosis group and no ED group). If the three-way interaction was not significant, the sample would be analyzed as a whole. Second, we ran two models using PROCESS Model 1 examining the interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with (1) ED symptoms and (2) ED-related impairment. In this analysis, adaptive ER was used as the moderator of interest during the interpretation of the results. This is because it may be more clinically important to understand when adaptive ER modifies the influence of maladaptive ER on psychopathology. Third, to replicate prior meta-analytic work [3, 6] and confirm that our adaptive and maladaptive variables were performing as expected, we ran two regression models analyzing the main effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with (1) ED symptoms and (2) ED-related impairment.

Results

H1: three-way interaction with lower order interactions and conditional effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

First, we tested the three-way interaction between adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis including all lower level interactions and conditional effects with ED symptom score and ED-related impairment.Footnote 1 Neither the three-way interaction between adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis with ED symptoms (p = 0.190) nor the three-way interaction with ED-related impairment (p = 0.054) were significant. This was contrary to our hypothesis that there would be a significant three-way interaction between adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and probable ED diagnosis. Given that this interaction was not significant, we continued our analysis by examining the sample as a whole, instead of two groups (i.e., probable ED and non-probable ED status).

H2: two-way interaction with conditional effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

Second, we ran a regression with ED symptom score, entering adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and their interaction. There were conditional effects of both ER strategies, such that adaptive ER was negatively associated with ED symptom score, B = − 0.497, SE = 0.072, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.638, − 0.356], whereas maladaptive ER was positively associated with ED symptom score, B = 0.189, SE = 0.069, p = 0.006, 95% CI [0.054, 0.324]. The interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with the outcome of ED symptoms was significant, B = 0.016, SE = 0.008, p = 0.035, 95% CI [0.001, 0.030]. This model explained about 3.8% of the variance, F(3, 1373) = 18.21, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.0383.

The Johnson–Neyman technique identified the statistically significant transition point at the 33.4th percentile, such that the interaction transitioned from being nonsignificant to being significant beyond this point. At lower levels of adaptive ER (< 33.4th percentile), there was no relationship between maladaptive ER and ED symptoms. Therefore, maladaptive ER was significantly positively associated with ED symptoms for all values above this transition point and there were significant positive relationships between maladaptive ER and ED symptom score for average and high levels of adaptive ER. For average levels of adaptive ER (50th percentile), every unit increase in maladaptive ER resulted in an increase of 0.202 units on ED symptoms, B = 0.202, SE = 0.069, p = 0.004, 95% CI [0.066, 0.338]. At high levels of adaptive ER (84th percentile; 1 SD above mean), every unit increase in maladaptive ER increased 0.297 units on ED symptoms, B = 0.297, SE = 0.088, p = 0.001, 95% CI [0.125, 0.469]. This was consistent with our prediction that adaptive ER would moderate the relationship between maladaptive ER and ED symptom score, specifically supporting the compensatory hypothesis. See Table 2 for a summary of results and Fig. 2 for two-way interaction results.

Third, we ran a regression with ED-related clinical impairment entering adaptive ER, maladaptive ER, and their interaction. Conditional effects were found for adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with ED-related impairment, such that adaptive ER was negatively associated with clinical impairment, B = − 0.406, SE = 0.041, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.488, − 0.325] and maladaptive ER was positively associated with clinical impairment, B = 0.156, SE = 0.040, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.078, 0.234]. The interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER for clinical-related impairment was not significant (p = 0.124). This was contrary to our hypothesis that adaptive ER would moderate the association between maladaptive ER and impairment related to eating disorders.

H3: main effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER

Lastly, we conducted regressions to test the main effects of habitual adaptive ER and maladaptive ER for ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. In the regression model testing for main effects, adaptive ER and maladaptive ER were significantly associated with ED symptoms. The overall regression model was significant, F(2, 1374) = 25.031, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.035. Consistent with H3, adaptive ER was negatively associated with ED symptoms, B =− 0.504, SE = 0.072, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.644, − 0.363], whereas maladaptive ER was positively associated with ED symptoms, B = 0.182, SE = 0.069, p = 0.008, 95% CI [0.047, 0.317]. See Table 2.

Moreover, adaptive ER and maladaptive ER were significantly associated ED-related impairment, consistent with H3. The overall regression model was significant, F(2, 1374) = 49.679, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.067. As predicted in H3, adaptive ER was negatively associated with ED-related impairment, B =− 0.409, SE = 0.041, p < 0.001, 95% CI [− 0.490, − 0.328], whereas maladaptive ER was positively associated with ED-related impairment, B = 0.153, SE = 0.040, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.075, 0.231].

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to expand our understanding of the ER repertoire as it relates to ED symptoms. To do this, we moved from a framework of looking at ER strategies as individual predictors, to examining interactions between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. We anticipated that the interaction effects would differ according to participants’ clinical case status. However, we did not find a significant three-way interaction for both outcome variables. That is, clinical case status did not play a role as a contextual factor in the sample. This result was not anticipated; however, a possible reason for our finding is that the proportion of clinical participants (n = 510, 37%) was not large enough or of high enough severity to detect the three-way interaction.

In our sample, the overall CIA score mean was 14.669, which was slightly lower the cutoff point (CIA score = 16) that predicts ED case status [29, 30]. Hence, our sample as a whole demonstrated lower level of severity for ED-related impairment than clinical samples, yet may have been elevated compared to other community samples. Furthermore, previous studies that investigated interactions in clinical samples recruited individuals with interviewer-diagnosed mental disorders or treatment-seeking samples, whereas our sample was classified based on self-reported symptoms. For instance, in a research study examining the interactions between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER in generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), the sample consisted of 107 individuals diagnosed via interview with GAD and 98 controls with no diagnosis [15]. The pattern of interactions depended on clinical case status, such that the interference effect was found in individuals diagnosed with GAD; the compensatory effect was found in non-anxious controls. In addition, when Aldao et al. examined interactive effects in a clinical sample [13], they recruited treatment-seeking individuals who were diagnosed for social anxiety disorder according to the DSM-IV. The authors replicated the interference and compensatory hypotheses in treatment-seeking individuals who showed high level of social anxiety symptoms and those who had fewer symptoms after treatment, respectively. It is possible that using treatment-seeking or interviewer-diagnosed participants would produce different results than our sample, which used university students who were self-reporting symptoms. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings in other sample types.

Our second hypothesis was that there would be a significant two-way interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER for ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. Our results partly supported this hypothesis; we found a significant interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER with ED symptoms. Our findings revealed that there were significant positive associations between maladaptive ER and ED symptom score for average and high levels of adaptive ER. In other words, adaptive ER moderated the association between maladaptive ER and ED symptoms only when adaptive ER was at average and high levels. This pattern of interaction is consistent with the compensatory hypothesis, which suggests that maladaptive ER is associated with ED symptoms, only when adaptive ER is high [2]. On the other hand, for those low in the adaptive ER strategy, maladaptive ER was not associated with ED symptoms (rather, these participants reported elevated ED symptoms across all levels). In summary, even small amounts of maladaptive ER are problematic when people report low levels of adaptive ER; however, when adaptive ER is higher, it can temper the extent to which maladaptive ER is associated with elevated ED symptoms. This pattern of results suggests that high adaptive ER “compensates” for the deleterious effects of maladaptive ER.

An alternative explanation to consider is that people with higher levels of ED pathology may have greater emotion dysregulation and, thus, greater need for ER, which could require them to employ both adaptive and maladaptive strategies. There may be some partial support for this hypothesis, as people at medium and high levels of adaptive strategies who also used maladaptive strategies reported greater symptoms than those who used medium and high levels of adaptive strategies and low maladaptive strategies. Conversely, although we did not examine our data using contrast analysis, a visual inspection of the interaction graph suggests that those who were highest in ED symptoms were lowest in adaptive ER (and the level of maladaptive ER is unrelated to pathology). In other words, the most severe participants were not using both strategies most frequently. Another possibility is that for individuals with the highest levels of ED symptoms, who may need to regulate high-intensity emotions, using reappraisal may not be an effective strategy and thus people do not use it (e.g., [21,23, 33, 34]). More research evaluating the need for regulation, as well as which strategies are used and their efficacy, is important to better evaluate this phenomenon.

An important context for these findings is the potential emotion regulatory role of ED behaviors. Theoretical models, such as the Affect Regulation Model, suggest that disordered eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating, compensatory behaviors) may function as ER strategies (e.g., [35,36,37]). For example, individuals with binge eating disorder may engage in binge eating to downregulate negative affect [38]. It is worth investigating how the use of ED behaviors may fit into the ER repertoire and their relationship to cognitive strategies (e.g., if behavioral strategies are used when cognitive strategies are ineffective or vice versa). Along these lines, future research is needed to better understand the temporal ordering of cognitive ER strategies (e.g., distraction, suppression, and reappraisal) and behavioral strategies (i.e., ED behaviors).

We did not find a significant interaction between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER for ED-related impairment, although we found significant associations between both ER strategies and ED-related impairment. This may be because ED-related clinical impairment may be a more distal outcome than symptoms (e.g., impairment may be influenced by symptoms, social support, context), and thus could be subject to additional mitigating factors. Hence, it might be easier to detect the interactive effects of ER strategies on ED symptoms than ED-related impairment outcome. On the other hand, one previous study found a significant interaction in support of the compensatory hypothesis that used disability as an outcome variable [15]; however, these findings have yet to be replicated. Thus, it is necessary to continue to examine disability and impairment status in the ED population.

For our third hypothesis, we predicted that adaptive ER would be negatively associated with ED symptoms and ED-related impairment, whereas maladaptive ER would be positively associated with both outcome variables. Our results were consistent with this hypothesis and replicated previous findings that the two categories of ER (i.e., adaptive and maladaptive) are associated with psychopathology in opposite directions [3, 6].

Results from this study may contribute to future research on the potential effectiveness of teaching adaptive ER in clinical settings. Although additional longitudinal research is needed to confirm our findings, the current study provides initial evidence to suggest that ER repertoire is associated with symptom severity. Future research may wish to examine if changing ER repertoires can decrease ED symptoms.

Strengths and limits

This study is the first study to examine the interactive effects of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER in ED and contributes to a more nuanced understanding of the role of ER strategies in ED and ED-related impairment. However, it is important to note several limitations. Our sample did not use a clinically diagnosed or treatment-seeking sample, which could be why we did not find a significant three-way interaction. Future studies may recruit these types of participants to better study differences in the interactions of adaptive ER and maladaptive ER between those with and without ED diagnoses. The study relied on self-report data on measures of ED symptoms. Although the EDDS demonstrated criterion validity with clinical interview diagnoses [28], the use of self-report has some shortcomings, including potential inconsistencies in how questions are interpreted and tendencies to under-report weight and over-report height [39]. However, self-report data is not necessarily problematic, as some research has suggested that increased rates of eating pathology are found in self-report assessments as compared to interview diagnoses because participants might feel more anonymous when completing a questionnaire [40]. Relatedly, the use of retrospective self-report measure to assess ER could be influenced by participants’ recall biases. For instance, people might report emotional experiences differently, when they depend on either episodic or semantic memory according to the phrasing of the questions (e.g., when asked to report on emotions over short or long timeframe) [41]. Furthermore, work using ecological momentary analysis has found no or low associations between reports of habitual ER strategy use and actual daily ER strategy use [42]. Thus, conducting studies that examine daily-level associations between ER strategies and ED symptoms could be informative to address potential recall bias. We only assessed three types of ER in this study, which are cognitive reappraisal (adaptive), distraction (maladaptive), and suppression (maladaptive). One’s repertoire of ER likely contains several additional ER strategies. Future studies are needed to replicate and extend by measuring other types of strategies. In line with previous research, this study measured the frequency of habitual ER use. Consequently, the results should not be interpreted as the effectiveness of a single ER strategy or the effectiveness of a repertoire of adaptive and maladaptive ER. An important next step for future research would be examining the effectiveness of ER, especially taking consideration the role of context in which the emotion is experienced and regulated. In addition, the majority of the participants in this study were cisgender White women; thus, we had less representation of men and individuals from other social groups. Consequently, findings might not generalize to the general population. Gender differences in emotion regulation have been discovered, revealing that women have the tendency to use ER strategies more than men [43, 44]. As compared to their heterosexual counterparts, individuals who identify as members of the LGBTQIA2S + community also report greater use of rumination and expressive suppression, which might result from greater minority stress experienced as a result of discrimination due to their sexual orientation and gender identities [45,46,47]. Future research should address these intergroup differences and examine any differing interactional effects of ER on ED symptoms and ED-related impairment. Lastly, given that our findings are based on a cross-sectional research design, the results cannot establish any causal link. Future studies could use experimental or ecological momentary assessment designs to test causality.

Conclusion

This paper extends the current knowledge of the ER as it relates to ED pathology by examining the interactions between adaptive ER and maladaptive ER, rather than main effects of each strategy. We found that adaptive ER and maladaptive ER interacted with each other in the association with ED symptoms, consistent with the compensatory hypothesis, but clinical case status did not play a role as a contextual factor. Given the null findings related to diagnosis, future studies are needed to test interactions in clinical or treatment-seeking samples. Overall, the results suggest the utility of considering ER repertoires and incorporating person-centered ER insights into clinical practice.

What is already known on this subject? Multiple studies have examined links between ER strategies and ED by studying the individual associations between different types of strategies and ED symptoms (see meta-analysis in [6]). However, growing evidence suggests that to better characterize ER profiles and risks for psychopathology, ER strategies must be examined in conjunction with each other. Two types of interaction patterns have been observed in clinical and non-clinical samples, which represent the interference and compensatory hypotheses, respectively.

What this study adds: This study extends previous work on associations between ER and eating pathology by examining how interactions between ER strategies are associated with ED symptoms. This is the first study to test the interference and compensatory hypotheses of ER strategy interactions in predicting ED symptoms and ED-related clinical impairment.

Availability of data and material

Participants of this study did not consent for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Notes

Of note, for all analyses, we initially entered age as a covariate. Age was not significantly associated with any outcomes and its inclusion did not change patterns of significance for other variables, therefore, for ease of interpretation, we present analyses unadjusted for age.

References

Gross JJ (1998) The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol 2(3):271–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2012) When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? J Abnorm Psychol 121(1):276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023598

Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S (2010) Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev 30(2):217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

McMahon TP, Naragon-Gainey K (2018) The moderating effect of maladaptive emotion regulation strategies on reappraisal: a daily diary study. Cognit Ther Res 42(5):552–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-018-9913-x

Berking M, Wupperman P (2012) Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directions. Curr Opin Psychiatr 25(2):128–134. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503669

Prefit AB, Cândea DM, Szentagotai-Tătar A (2019) Emotion regulation across eating pathology: a meta-analysis. Appetite 143:104438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104438

Visted E, Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Schanche E (2018) Emotion regulation in current and remitted depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 9:756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00756

Aldao A (2013) The future of emotion regulation research: capturing context. Perspect Psychol Sci 8(2):155–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459518

Aldao A, Christensen K (2015) Linking the expanded process model of emotion regulation to psychopathology by focusing on behavioral outcomes of regulation. Psycho Inq 26(1):27–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.962399

Christensen K, Aldao A (2015) Tipping points for adaptation: connecting emotion regulation, motivated behavior, and psychopathology. Curr Opin Psychol 3:70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.015

Plate AJ, Dunn EJ, Christensen K, Aldao A (2020) When are worry and rumination negatively associated with resting respiratory sinus arrhythmia? It depends: the moderating role of cognitive reappraisal. Cognit Ther Res 44:874–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10099-z

Christensen KA, van Dyk IS, Southward MW, Vaset MW (2021) Evaluating interactions between emotion regulation strategies through the interpersonal context of female friends. J Clin Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23214

Aldao A, Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Gross JJ (2014) Adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies: interactive effects during CBT for social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord 28(4):382–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.03.005

Conklin LR, Cassiello-Robbins C, Brake CA, Sauer-Zavala S, Farchione TJ, Ciraulo DA, Barlow DH (2015) Relationships among adaptive and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies and psychopathology during the treatment of comorbid anxiety and alcohol use disorders. Behav Res Ther 73:124–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.08.001

Plate AJ, Aldao A, Quintero JM, Mennin DS (2016) Interactions between reappraisal and emotional nonacceptance in psychopathology: examining disability and depression symptoms in generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Ther Res 40(6):733–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9793-x

Dixon-Gordon KL, Aldao A, De Los RA (2014) Repertoires of emotion regulation: a person-centered approach to assessing emotion regulation strategies and links to psychopathology. Cogn Emot 29(7):1314–1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.983046

Kleifield EI, Wagner S, Halmi KA (1996) Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr Clin North Am 19(4):715–737. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(05)70377-4

Levinson CA, Sala M, Fewell L, Brosof LC, Fournier L, Lenze EJ (2018) Meal and snack-time eating disorder cognitions predict eating disorder behaviors and vice versa in a treatment seeking sample: a mobile technology based ecological momentary assessment study. Behav Res Ther 105:36–42

Vanzhula IA, Sala M, Christian C, Hunt RA, Keshishian AC, Wong VZ, Ernst S, Spoor SP, Levinson CA (2020) Avoidance coping during mealtimes predicts higher eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 53(4):625–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23254

Sheppes G, Brady WJ, Samson AC (2014) In (visual) search for a new distraction: the efficiency of a novel attentional deployment versus semantic meaning regulation strategies. Front Psychol 5:346. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00346

Sheppes G, Meiran N (2007) Better late than never? On the dynamics of on-line regulation of sadness using distraction and cognitive reappraisal. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 33(11):1518–1532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207305537

Li P, Wang W, Fan C, Zhu C, Li S, Zhang Z, Qi Z, Luo W (2017) Distraction and expressive suppression strategies in regulation of high- and low-intensity negative emotions. Sci Rep 7:13062. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12983-3

Sheppes G, Scheibe S, Suri G, Radu P, Blechert J, Gross JJ (2014) Emotion regulation choice: a conceptual framework and supporting evidence. J Exp Psychol Gen 143(1):163–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030831

Gross JJ, John OP (2003) Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 85(2):348–362. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348

Gámez W, Chmielewski M, Kotov R, Ruggero C, Watson D (2011) Development of a measure of experiential avoidance: the Multidimensional Experiential Avoidance Questionnaire. Psychol Assess 23(3):692–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023242

Stice E, Telch CF, Rizvi SL (2000) Development and validation of the eating disorder diagnostic scale: a brief self-report measure of anorexia, bulimia, and binge-eating disorder. Psychol Assess 12(2):123–131. https://doi.org/10.1037//1040-3590.12.2.123

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, New York

Stice E, Fisher M, Martinez E (2004) Eating disorder diagnostic scale: additional evidence of reliability and validity. Psychol Assess 16(1):60–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.60

Bohn K, Fairburn CG (2008) The clinical impairment assessment questionnaire (CIA). In: Fairburn CG (ed) Cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders. Guilford Press, New York, pp 315–317

Reas D, Rø Ø, Kapstad H, Lask B (2010) Psychometric properties of the clinical impairment assessment: norms for young adult women. Int J Eat Disord 43(1):72–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20653

Christensen KA, Forbush KT, Richson BN, Thomeczek ML, Perko VL, Bjorlie K, Christian K, Ayres J, Wildes JE, Chana SM (2021) Food insecurity associated with elevated eating disorder symptoms, impairment, and eating disorder diagnoses in an American University student sample before and during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Eat Disord. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23517

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach, 2nd edn. Guilford Publications, New York

Sheppes G, Meiran N (2008) Divergent cognitive costs for online forms of reappraisal and distraction. Emotion 8:870–874. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013711

Sheppes G, Catran E, Meiran N (2009) Reappraisal (but not distraction) is going to make you seat: physiological evidence for self control effort. Int Psychophysiol 71:91–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.06.006

Cooper MJ, Wells A, Todd G (2004) A cognitive theory of bulimia nervosa. Br J Clin Psychol 43:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466504772812931

Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R (2003) Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: a ‘transdiagnostic’ theory and treatment. Behav Res Ther 41(5):509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8

Waller G, Kennerley H, Ohanian V (2007) Schema focused cognitive-behaviour therapy with eating disorders. In: Riso LP, du Poit PT, Young JE (eds) Cognitive schemas and core beliefs in psychiatric disorders: A scientist-practitioner guide. American Psychiatric Association, New York, pp 139–175

Evers C, Marijn Stok F, de Ridder DT (2010) Feeding your feelings: emotion regulation strategies and emotional eating. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 36(6):792–804. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210371383

Gorber SC, Tremblay M, Moher D, Gorber B (2007) A comparison of direct vs self-report measures for assessing height, weight and body mass index: a systematic review. Obes Rev 8(4):307–326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00347.x

Keel PK, Crow S, Davis TL, Mitchell JE (2002) Assessment of eating disorders: comparison of interview and questionnaire data from a long-term follow-up study of bulimia nervosa. J Psychosom Res 53(5):1043–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00491-9

Robinson MD, Clore GL (2002) Episodic and semantic knowledge in emotional self-report: evidence for two judgment processes. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(1):198–215. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.83.1.198

Brockman R, Ciarrochi J, Parker P, Kashdan TB (2016) Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cogn Behav Ther 46(2):1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1218926

Nolen-Hoeksema S (2012) Emotion regulation and psychopathology: the role of gender. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 8:161–187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109

Delhom I, Melendez JC, Satorres E (2021) The regulation of emotions: gender differences. Eur Psychiatry 64(S1):S836. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.2209

Hatzenbuehler ML, Dovidio JF, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Phills CE (2009) An implicit measure of anti-gay attitudes: prospective associations with emotion regulation strategies and psychological distress. J Exp Soc Psychol 45(6):1316–1320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.08.005

Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S (2008) Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 49(12):1270–1278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x

Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J (2009) How does stigma “get under the skin”? The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci 20(10):1282–1289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x

Funding

This research is supported by the University of Kansas Research Excellence Initiative (REI) Grant to Kelsie Forbush (PI). KAC is supported by a CTSA grant from NCATS awarded to the University of Kansas for Frontiers: University of Kansas Clinical and Translational Science Institute (# TL1TR002368). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the University of Kansas, NIH, or NCATS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have not disclosed any competing interests.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board, thereby in accordance with the ethical standards (STUDY00144380).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Won, Y.Q., Christensen, K.A. & Forbush, K.T. Habitual adaptive emotion regulation moderates the association between maladaptive emotion regulation and eating disorder symptoms, but not clinical impairment. Eat Weight Disord 27, 2629–2639 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01399-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-022-01399-2