Abstract

Background

Dietary rules are common in patients with eating disorders, and according to transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural theory for eating disorders, represent a key behaviour maintaining eating-disorder psychopathology. The aim of this study was to describe the design and validation of the Dietary Rules Inventory (DRI), a new self-report questionnaire that assesses dietary rules in patients with eating disorders.

Methods

A transdiagnostic sample of 320 patients with eating disorders, as well as 95 patients with obesity and 122 healthy controls were recruited. Patients with eating disorders also completed the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ), the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, the Brief Symptoms Inventory and the Clinical Impairment Assessment. Dietary rules were rated on a continuous Likert-type scale (0–4), rating how often (from never to always) they had been applied over the previous 28 days.

Results

DRI scores were significantly higher in patients with eating disorders than in patients with obesity and healthy controls. Principal factor analysis identified that 55.8% of the variance was accounted for by four factors, namely ‘what to eat’, ‘social eating’, ‘when and how much to eat’ and ‘caloric level’. Both global score and subscales demonstrated high internal and test–retest reliability. The DRI global score was significantly correlated with the DEBQ ‘restrained eating’ subscale, as well as eating-disorder and general psychopathology and clinical impairment scores, demonstrating good convergent validity.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the DRI is a valid self-report questionnaire that may provide important clinical information regarding the dietary rules underlying dietary restraint in patients with eating disorders.

Level of evidence

V, descriptive study

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Dietary restraint, defined as the attempt to restrict food intake to lose weight or prevent weight gain [1], has been proposed as a key mechanism involved in the maintenance of overeating and binge-eating episodes [2,3,4]. The ‘dietary restraint hypothesis’ has been supported by some laboratory studies, which have found that overeating often occurs as a response to a pre-load disrupting the cognitive attempt of eating control in participants with high dietary restraint levels [3, 5,6,7]. However, the causal relationship between dietary restraint and overeating/binge eating has not been confirmed by other studies [8,9,10,11,12,13]. These discrepancies in the results have been attributed by some authors to different methods used to measure dietary restraint [6, 14, 15].

The first measure of restrained eating (i.e. the restraint scale—RS) was developed by Herman and Polivy in 1975 [1] to identify normal-weight individuals who kept a suppressed body weight with persistent dieting. The use of RS has subsequently permitted to show that normal-weight restrained individuals differ from normal-weight unrestrained individuals in several behavioural, cognitive, and physiological measures [19,20,21]. Nonetheless, the conceptual and psychometric validity of the RS has been called into question [3] because it does not differentiate between food restriction and disinhibition of restraint, and it also measures weight fluctuations [22].

The Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ; [22]) and the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ; [23]), both including a scale measuring dietary restraint, have been proposed as alternative measures of dietary restraint. The DEBQ (DEBQ-R) ‘restrained eating’ scale has 10 items assessing intentions to restrict food intake for weight control reasons.

The restraint scales of the RS, TFEQ and DEBQ questionnaires are often significantly correlated, but they seem to assess different constructs. Indeed, the RS scores are not necessarily related to lower average caloric intake, as it assesses also weight fluctuations and disinhibited eating, whereas the restraint factors of the TFEQ and the DEBQ assess “pure” dietary restraint, as they dissociate restrained eating from overeating [24].

That being said, RS, TFEQ and DEBQ questionnaires were primarily designed for use in normal-weight patients without eating disorders or patients with obesity; to our knowledge, only three prior studies using restraint scales have included individuals with eating disorders, mainly binge-eating disorder. The paucity of restraint studies in patients with eating disorders, especially those with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa [15, 25, 26], in addition to the small sample sizes and mixed findings to date, means that additional research into this topic is warranted.

Indeed, it is well known that most patients with an eating disorder adopt a particularly rigid form of dietary restraint, with multiple extreme dietary rules. Rather than having general guidelines about how they should eat, people with eating disorders set themselves many demanding, and highly specific dietary rules designed to limit the amount that they eat. These rules vary in nature, but typically regard when, how much, and what they should eat. As a result of these rules, their eating becomes restricted and inflexible in nature.

According to cognitive behavioural theory, dietary restraint represents a clinical feature of overvaluation of shape, weight and eating and their control, and is one of the more powerful mechanisms maintaining binge-eating episodes [27]. However, to date, no instrument has been designed to evaluate the dietary rules underlying dietary restraint that patients with eating disorders apply to the control of eating. The assessment of dietary rules (i.e. intentionally trying to limit the food intake) promoting potentially dysfunctional eating behaviours could aid the clinicians and patients to better identify dysfunctional beliefs that sustain these rules and address them during the treatment.

For this reason, the aim of this study was to assess the psychometric proprieties of a novel tool, the Dietary Rules Inventory (DRI), designed to evaluate dietary rules in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders.

Methods

Participants

The sample of patients with eating disorders was recruited from the inpatient unit of Villa Garda Hospital (northern Italy), and from an outpatient eating disorder clinic serving the Verona area of Italy. Inclusion criteria were: (i) meeting the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for feeding and eating disorders [28], (ii) age 13–65 years, and (iii) signing the informed consent. The exclusion criterion was not being available to participate in the study.

The final sample was comprised of 320 patients with eating disorders aged between 13 and 61 years. DSM-5 diagnosis was performed by experts in eating disorders using the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview (Italian version) [29]. Two hundred and eight patients were recruited from the inpatient unit and 112 from the outpatient clinic.

Other two groups were included to enable an analysis of their differences with respect to the eating-disorder sample. The first group comprised individuals with obesity admitted to a residential rehabilitative treatment programme at Villa Garda Hospital, Verona, Italy from May to October 2020. The only inclusion criterion was the availability to participate in the study and the signing of the informed consent. The exclusion criterion was meeting the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders, including binge-eating disorder, as measured using the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview by assessors trained and supervised by RDG, an expert on the tool. A total of 95 patients with obesity were included.

The second group included healthy controls recruited among university students and staff members. Participants were excluded if they scored 20 or more on the validated Italian version of Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26) [30, 31] (N = 8) and/or reported a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (N = 17) and/or they stated that they were dieting, and had lost at least 10% of their weight in the preceding month (N = 8). No participant declared having or being treated for an eating disorder. A total of 122 participants were included. Weight and height were self-reported.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Verona and Rovigo (Project identification code 8571). All participants provided informed written consent for the anonymous use of their data for research purposes. For minors (< 18 years), additional informed consent was provided by their parents.

Measures

Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ)

The DEBQ is a 33-item self-report tool assessing three distinct eating behaviours, namely emotional eating, external eating and restrained eating. Items on the DEBQ are scored on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often), with higher scores indicating greater endorsement of the eating behaviour [23]. The Italian version was administered [32], and the three subscales were used to assess the convergent reliability of DRI.

Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

The EDE-Q [33] is a self-report questionnaire assessing eating disorders attitudes and behaviours in the last 28 days. The tool has four subscales (i.e. “restraint”, “eating concern”, “weight concern” and “shape concern”) and a global score. The validated Italian version of the EDE-Q 6.0 [34] was used to evaluate the relationship between DRI scores and eating-disorder psychopathology and, in particular, to assess the convergent validity of DRI using the EDE-Q “restraint” subscale.

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)

The global severity index (GSI) of the validated Italian version of BSI was used [35, 36] to assess the relationship between DRI scores and general psychopathology.

Clinical impairment assessment (CIA)

The CIA is a 16-item self-report instrument designed to evaluate functional impairment secondary to eating disorder [37]. The validated Italian version was administered [38]. The global score was used to assess the relationship between DRI scores and clinical impairment.

Tool design

Dietary Rules Inventory (DRI)

The DRI was developed in Italy and was designed to identify dietary rules in patients with eating disorders. Items were generated by taking into consideration clinical observations from patients’ reports, and through multiple discussions among researchers and clinicians expert in eating disorders.

An initial pool of items was selected by consensus after discussion among the authors on which to include or discount with a view to obtaining a comprehensive description of dietary restraint behaviours. This process resulted in 30 items, to be rated by participants according to how often they intentionally engaged in these behaviours in the preceding 28 days on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘never’ (0) to ‘always’ (4). The dietary rules mainly concern how much (i.e. establishing a caloric level to adhere to; having small portions; eating less than others), when (i.e. not eating beyond a set time; delaying mealtimes), and what (i.e. not eating foods considered fattening; not eating certain food groups [carbs, fats]; not using condiments) to eat. Other common dietary rules are included, such as, for example, not eating together with others, and not eating food cooked by others.

Administration of the DRI

To assess the validity of the tool, the DRI questionnaire was administered before treatment (the first day of hospitalisation or of therapy for inpatients and outpatients, respectively) to all participants with eating disorders (Time 1). All patients answered all items. To assess the test–retest reliability of the tool, a randomly selected subgroup of 53 patients (39 inpatients and 14 outpatients) were also administered the questionnaire during their pre-treatment assessment interview, 1–4 weeks before inpatient or outpatient treatment (Time 0).

Statistical analysis

Construct validity was assessed using principal axis factoring (PAF) with oblique rotation (hypothesising that identified factors would be correlated) and Kaiser normalisation [39] applied to the answers of patients with eating disorder to the 30 DRI items, rated along the Likert scale. According to the recommendations of factor analysis [40], the total number of questionnaires to administer was calculated in advance, and to ensure a satisfactory subject-to-item ratio (10:1). Moreover, Kaiser–Meier–Olkin (KMO) analysis and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to assess sampling adequacy (KMO > 0.60) [41]. The number of factors to be extracted was defined by: (i) examining the scree plot; (ii) using components with an eigenvalue > 1; (iii) assessing their interpretability and consistency with the hypotheses used to develop the tool. Items with factor loadings lower than 0.30 were deleted, to include only items that were related to the factor [42, 43]. Item–total correlations were also examined for each factor.

Internal consistency was assessed with Cronbach’s alpha. Then, test–retest reliability was assessed with Pearson’s correlation coefficients in the random subgroup of 53 patients who repeated the DRI (at Time 0 and Time 1). Next, convergent validity was assessed with Pearson’s correlation, relating DRI with DEBQ and EDE-Q global and subscale scores and with BSI and CIA global scores. Finally, criterion validity was tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc for multiple comparisons, comparing global DRI scores for the eating-disorder sample with those of patients with obesity and healthy controls. The same comparison was performed controlling for age and gender. IBM SPSS Statistics 27.0 (SPSS, Chicago, USA) was used to analyse all data.

Results

The characteristics of the 320 subjects with eating disorders, 95 patients with obesity and 122 healthy controls are shown in Table 1. As expected, there was a higher percentage of females and a lower average age in patients with eating disorders than in patients with obesity. Among the patients with eating disorders, about 57% of the sample met the DSM-5 criteria for anorexia nervosa and about 16% for bulimia nervosa.

Construct validity

A correlation between factors potentially obtainable from factor analysis was assumed, and a PAF with oblique rotation was performed. The KMO was 0.94, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (p < 0.001), indicating that data were suitable for factor analysis. The best solution was obtained using promax rotation and excluding two items, specifically #17 and #25. Item 17 (‘not accepting offers of food’) displayed cross-loading in three factors, and item 25 (‘eating certain foods a fixed number of times a week’) yielded a factor loading lower than 0.30; hence both were deleted from the tool.

Thus, the final version of the questionnaire comprised 28 items, with four factors extracted that together accounted for 55.8% of the items’ variance, as shown in Table 2. The first factor identified was termed ‘what to eat’, which comprised 8 items, the second was ‘social eating’, with 7 items, the third was ‘when and how much to eat’ with 11 items, and the fourth ‘caloric level’ with 2 items. All items showed moderate and high item–factor correlation (Table 2). The global score of each subscale was obtained by adding the items and dividing by the number of items.

Reliability

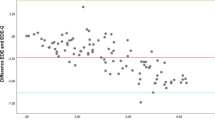

Cronbach’s alpha for the global score was 0.955, and for the four factors, it was: 0.92 for ‘what to eat’, 0.86 for ‘social eating’, 0.88 for ‘when and how much to eat’ and 0.92 for ‘caloric level’. Intraclass correlation indicated a coefficient of 0.95 for the global score, 0.92 for ‘what to eat’, 0.89 for ‘social eating’, 0.88 for ‘when and how much to eat’ and 0.92 for ‘caloric level’. Moreover, the test–retest reliability calculated using the DRI responses given by patients at initial assessment and again 4–22 days (mean 11.6 ± 5.0 days) later, was r = 0.88 for the global score, r = 0.90 for the ‘what to eat’, r = 0.77 for the ‘social eating’, r = 0.84 for the ‘when and how much to eat’, and r = 0.72 for the ‘caloric level’ factors (all ps < 0.001).

Convergent validity

To measure the convergent validity of the instrument in patients with eating disorders, the global DRI scores and factors were correlated with a validated instrument measuring dietary restraint, and with eating-disorder and general psychopathology measures. As shown in Table 3, DRI global and subscale scores were strongly correlated with DEBQ ‘restrained eating’, but only weakly or not correlated with DEBQ ‘emotional eating’, ‘external eating’ and global score. Moreover, a moderate and high association between DRI and EDE-Q global score and subscales was found; in particular, EDE-Q ‘restraint’ subscale displayed a higher correlation with DRI global and subscale scores than all other EDE-Q subscales. Moreover, DRI ‘social eating’ exhibited a higher correlation with BSI and CIA global scores than other DRI subscales. Finally, only a very weak relationship was found between DRI global and subscale scores and BMI. We also found that age was only weakly correlated with age (Pearson correlation from -0.03 with DRI ‘social eating’ subscale and − 0.16 with DRI ‘when and how much to eat’ subscale).

Group mean comparison

ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni correction was used to compare DRI global and subscale scores in patients with eating disorders, patients with obesity and healthy controls. Data indicated that patients with eating disorders had higher scores than both patients with obesity and healthy controls, whereas scores for patients with obesity and healthy controls did not differ significantly (Table 4). No significantly different results were obtained controlling the data for age and gender.

The three most frequent diagnoses of eating disorders (i.e. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorders) were compared on the DRI global and subscale scores. Data indicated that patients with anorexia nervosa showed higher scores than patients with binge-eating disorders on the global DRI and the subscale ‘what to eat’ and ‘when and how much to eat’ scores (p = 0.22, p = 0.10, p = 0.04, respectively). Moreover, patients with bulimia nervosa showed higher scores than patients with binge-eating disorders on the DRI ‘what to eat’ score (p = 0.017). No other differences were found.

The Appendix A in supplementary material shows the translated and not validated English version of the DRI.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the psychometric proprieties (i.e. internal consistency, test–retest reliability, dimensional structure and convergent validity) of the DRI in a large group of patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders, and to compare their scores with those of a healthy control sample and with patients with obesity. There were four main findings. First, as regards the DRI construct validity, PAF indicated that the four-factor solution was the best for patients with eating disorders, as it accounted for 55.8% of the variance. The four factors identified were ‘what to eat’ (which includes items regarding what types of foods were eaten), ‘social eating’ (concerning items about eating when other people are present), ‘when and how much to eat’ (including items about amount and time to eat), and ‘caloric level’ (two items about establishing a fixed calorie intake). These subscales reflect the specific types of dietary rules postulated by Fairburn as underlying dietary restraint, a specific clinical expression of eating-disorder psychopathology [27].

Second, the four subscales and global score of the DRI also demonstrated excellent internal consistency and high test–retest reliability. This indicates not only that both DRI global and subscales scores measure well-identified constructs, but also that the tool’s performance is stable over time. Similar results were obtained with the original validation of DEBQ restrained eating subscale and with the RS and TFEQ scales measuring dietary restraint in different populations (i.e. patients with obesity, without obesity, men and women) [1, 22, 23].

Third, concerning the convergent validity of the tool, both the global DRI and the four subscale scores were significantly correlated with DEBQ ‘restrained eating’, but weakly or not correlated with DEBQ ‘emotional eating’ and ‘external eating’. In line with previous literature, DEBQ ‘restrained eating’ was also not correlated with the other two DEBQ subscale scores [32, 44, 45]. Similarly, EDE-Q ‘restraint’ subscale showed a higher correlation with DRI global and subscales scores than all other EDE-Q subscales. These data support the ability of the DRI to measure restrained eating specifically, as opposed to eating concerns or other components of eating behaviours. Furthermore, the DRI scores, in particular, DRI ‘social eating’, were highly associated with BSI and CIA global scores, indicating that rules about social eating seem to impair, more than others, the quality of life and general psychopathology of patients with eating disorders.

Fourth, there were significant differences between patients with eating disorders and patients with obesity and healthy controls in terms of DRI scores, confirming the ability of the tool to discriminate between these samples. This difference indicates that, although also patients with obesity and healthy controls may have dietary rules, patients with eating disorders apply these rules with significantly higher rigidity due to specific eating-disorder psychopathology.

Nevertheless, the DRI could be able to detect dietary rules and their rigidity in patients with eating disorders (especially anorexia nervosa), and to discriminate these from other samples without eating disorders. The strength of this finding is bolstered by the use of a large transdiagnostic sample of treatment-seeking individuals with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. Furthermore, the inclusion of healthy control and obesity patient samples lends weight to the psychometric and clinical validity of the tool.

However, the study itself does have some limitations. First, the results cannot be generalized to all individuals with eating disorders, as the sample is not big enough to represent the population of patients with eating disorders, and also included few males and a prevalent percentage of patients with anorexia nervosa. Second, the instrument was developed in Italy and the inclusion of items could be influenced by Italian eating tradition. Third, the factor structure of the DRI was determined with an exploratory method. Fourth, DRI was not developed to evaluate the relationship between emotion regulation and dietary restraint and no conclusion may be drawn about the role of restraint as potential emotive regulation strategy. Future studies should assess the performance of DRI items with a confirmatory factor analysis or an item-response theory analysis.

Bearing in mind all the limitations, the DRI could be a useful tool for measuring dietary rules in patients with eating disorders. It is quick and easy to complete and could, therefore, be readily integrated into routine clinical practice, providing a better understanding of the dietary rules driving eating behaviours in patients with eating disorders, and therefore, targets for intervention.

What is already known on this subject?

-

The relationship between dietary restraint and overeating is only partially supported by previous studies.

-

Mixed results of the studies, mainly including patients with obesity or normal-weight subjects, seem due to different methods used to measure dietary restraint.

-

Patients with eating disorders adopt a particular form of dietary restraint, characterised by multiple extreme and rigid dietary rules. To date, no instrument has been specifically designed to evaluate the dietary rules underlying dietary restraint in patients with eating disorders.

What this study adds?

-

The Dietary Rules Inventory is a useful self-report tool to identify dietary rules underlying dietary restraint in patients with eating disorders.

-

In the clinical practice, the instrument could permit to assess the dietary rules to address during treatment with the aim to reduce eating-disorder psychopathology.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Herman CP, Mack D (1975) Restrained and unrestrained eating. J Pers 43(4):647–660

Ruderman AJ, Wilson GT (1979) Weight, restraint, cognitions and counterregulation. Behav Res Ther 17(6):581–590

Ruderman AJ (1986) Dietary restraint: a theoretical and empirical review. Psychol Bull 99(2):247–262

Polivy J, Herman CP (1985) Dieting and binging. A causal analysis. Am Psychol 40(2):193–201

Heatherton TF, Herman CP, Polivy J, King GA, McGree ST (1988) The (Mis)measurement of restraint: an analysis of conceptual and psychometric issues. J Abnorm Psychol 97(1):19–28

Lowe MR, Levine AS (2005) Eating motives and the controversy over dieting: eating less than needed versus less than wanted. Obes Res 13(5):797–806

Polivy J (1996) Psychological consequences of food restriction. J Am Diet Assoc 96(6):589–592

Dritschel B, Cooper PJ, Charnock D (1993) A problematic counter-regulation experiment: implications for the link between dietary restraint and overeating. Int J Eat Disord 13(3):297–304

Jansen A, Merckelbach H, Oosterlaan J, Tuiten A, van den Hout M (1988) Cognitions and self-talk during food intake of restrained and unrestrained eaters. Behav Res Ther 26(5):393–398

Lawson OJ, Williamson DA, Champagne CM, DeLany JP, Brooks ER, Howat PM, Wozniak PJ, Bray GA, Ryan DH (1995) The association of body weight, dietary intake, and energy expenditure with dietary restraint and disinhibition. Obes Res 3(2):153–161

Lowe MR, Kleifield EI (1988) Cognitive restraint, weight suppression, and the regulation of eating. Appetite 10(3):159–168

Smith CF, Geiselman PJ, Williamson DA, Champagne CM, Bray GA, Ryan DH (1998) Association of dietary restraint and disinhibition with eating behavior, body mass, and hunger. Eat Weight Disord 3(1):7–15

Wardle J, Beales S (1987) Restraint and food intake: an experimental study of eating patterns in the laboratory and in normal life. Behav Res Ther 25(3):179–185

Ouwens MA, van Strien T, van der Staak CP (2003) Tendency toward overeating and restraint as predictors of food consumption. Appetite 40(3):291–298

Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR (2004) Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not. Psychol Assess 16(1):51–59

Schachter S, Rodin J (1974) Obese humans and rats. Erlbaum/Halsted, Washington

Nisbett RE (1972) Hunger, obesity, and the ventromedial hypothalamus. Psychol Rev 79(6):433–453

Herman CP, Polivy J (1975) Anxiety, restraint, and eating behavior. J Abnorm Psychol 84(6):66–72

Herman CP, Polivy J (1984) A boundary model for the regulation of eating. In: Stunkard AJ, Stellar E (eds) Eating and its disorders. Raven Press, New York, pp 141–156

Lowe MR (1993) The effects of dieting on eating behavior: a three-factor model. Psychol Bull 114(1):100–121

Lowe MR, Kral TV (2006) Stress-induced eating in restrained eaters may not be caused by stress or restraint. Appetite 46(1):16–21

Stunkard AJ, Messick S (1985) The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 29(1):71–83

van Strien T, Frijters JER, Bergers GPA, Defares PB (1986) The Dutch eating behavior questionnaire (DEBQ) for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating behavior. Int J Eat Disord 5(2):295–315

Laessle RG, Tuschl RJ, Kotthaus BC, Pirke KM (1989) A comparison of the validity of three scales for the assessment of dietary restraint. J Abnorm Psychol 98(4):504–507

Stice E, Sysko R, Roberto CA, Allison S (2010) Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of dietary restriction? Additional objective behavioral and biological data suggest not. Appetite 54(2):331–339

Sysko R, Walsh BT, Fairburn CG (2005) Eating disorder examination-questionnaire as a measure of change in patients with Bulimia Nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 37(2):100–106

Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guilford Press, New York

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association, Washington

Calugi S, Ricca V, Castellini G, Lo Sauro C, Ruocco A, Chignola E, El Ghoch M, Dalle Grave R (2015) The eating disorder examination: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord 20(4):505–511

Garner DM, Olmsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12(4):871–878

Dotti A, Lazzari R (1998) Validation and reliability of the Italian Eat-26. Eat Weight Disord 3(4):188–194

Dakanalis A, Zanetti MA, Clerici M, Madeddu F, Riva G, Caccialanza R (2013) Italian version of the Dutch eating behavior questionnaire. Psychometric proprieties and measurement invariance across sex, bmi-status and age. Appetite 71:187–195

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ Eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0). In: Fairburn CG (2008) Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. Guiford Press, New York, pp 309–313

Calugi S, Milanese C, Sartirana M, El Ghoch M, Sartori F, Geccherle E, Coppini A, Franchini C, Dalle Grave R (2016) The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire: reliability and validity of the Italian version. Eat Weight Disord 22:509–514

De Leo D, Frisoni GB, Rozzini R, Trabucchi M (1993) Italian Community norms for the brief symptom inventory in the elderly. Br J Clin Psychol 32(Pt 2):209–213

Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N (1983) The brief symptom inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med 13(3):595–605

Bohn K, Doll HA, Cooper Z, O’Connor M, Palmer RL, Fairburn CG (2008) The measurement of impairment due to eating disorder psychopathology. Behav Res Ther 46(10):1105–1110

Calugi S, Sartirana M, Milanese C, El Ghoch M, Riolfi F, Dalle Grave R (2018) The clinical impairment assessment questionnaire: validation in Italian patients with eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 23(5):685–694

Tabachnick BG, Fidell SL (2013) Principal components and factor analysis. In: Using multivariate statistics. Pearson, Boston

Gorusch RL (1983) Factor analysis, 2nd edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39:31–36

Kline P (1994) An easy guide to factor analysis. Routledge, New York

Stevens JP (1992) Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences, 2nd edn. Erlbaum, Hillsdale

Baños RM, Cebolla A, Etchemendy E, Felipe S, Rasal P, Botella C (2011) Validation of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire for Children (DEBQ-C) for use with Spanish children. Nutr Hosp 26(4):890–898

Halvarsson K, Sjoden PO (1998) Psychometric properties of the Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire (DEBQ) among 9–10-year-old Swedish girls. Eur Eat Disord Rev 6:115–125

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RDG and SC contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by SC, NM, CM, LD, MS and DF. The first draft of the manuscript was written by SC and RDG. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Verona and Rovigo (Project identification code 8571). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to participate

All the participants provided informed written consent for the anonymous use of their data for research purposes. For minors (<18 years), additional informed consent was provided by their parents.

Consent for publication

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Calugi, S., Morandini, N., Milanese, C. et al. Validity and reliability of the Dietary Rules Inventory (DRI). Eat Weight Disord 27, 285–294 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01177-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01177-6