Abstract

Purpose

Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (DEAB) in childhood have been prospectively associated with eating disorders and obesity in adolescence. Therefore, evaluating DEAB in children with a reliable, sensitive and well-adapted scale is very important. The Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT) is one of the most popular measuring tools for DEAB in children, but no French version is available. Moreover, while completion time is an important factor to be considered when working with children, only one recent study proposed a shorter version of the ChEAT. Taking the previous works of Murphy and colleagues (2019) as a starting point, the current study aimed to provide the first French-speaking validated 14-item short version of the ChEAT.

Methods

A sample of 1092 boys and girls aged between 8 and 12 years old were recruited in two urban areas in the province of Quebec, Canada. They completed the ChEAT, and their height and weight were measured at school. Factorial structure and internal consistency were assessed.

Results

After the initial factorial analysis, two “vomiting (or purging)” items were yielded as problematic and were thus removed from the analysis. The remaining 12 items provided a good fit to the data and a good internal consistency. Moreover, the factorial structure was proved to be invariant across sexes.

Conclusion

This study is the first to provide a French assessment of DEAB in elementary school children. The French short version of the ChEAT provided a quick and reliable assessment for DEAB with non-clinical children population and could be used as a screening tool, even though no cut-off was established yet.

Level of evidence

Cross-sectional, descriptive study, Level V.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

While eating disorders (ED) onset occurs commonly during adolescence [1, 2], first signs of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (DEAB) can be encountered in children as young as 6 and 7 years old [3]. DEAB include a broad selection of attitudes and behaviors with regards to weight, shape, and eating [4], like image distortion, dissatisfaction with body weight and shape, fear of weight gain, as well as food restriction, fasting, bulimic behaviors, vomiting, and binge eating [5,6,7]. Moreover, a high level of DEAB in childhood have been prospectively associated with ED development during adolescence [8], as well as with a higher risk of obesity [9], which stresses the importance of early detection of DEAB. Therefore, a reliable and sensitive scale for DEAB that is adapted for children is more than necessary.

Although there is a wide number of measures to assess DEAB among adult population that can be used with adolescents, few are adapted to children [10]. Among available measures for elementary school children, the most used are the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire adapted for children (ChEDE-Q [11, 12]), the Eating Disorder Inventory for children (EDI-C [13, 14]), and the Children’s Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT [15]). Of these three measures, the ChEAT is undoubtedly the preferred one to screen for DEAB in non-clinical populations because it provides a total score reflecting global severity of difficulties related to eating and weight which is simple and quick to calculate [16]. Also, its popularity arises from its wide accessibility, as the ChEAT has been translated and validated in numerous languages and countries such as the USA (English [4, 15, 17]), Spain (Spanish [18, 19]), Portugal (Portuguese [20]), Belgium (Dutch [21]), Japan (Japanese [22]), Sweden (Swedish [23]) and Finland (Finnish [24]). However, to our knowledge, the psychometric properties of a French version of the ChEAT have not been reported yet. Given that French is spoken in Canada as well as in many European (e.g., France, Belgium, Switzerland, Luzembourg) and North-African (e.g., Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia) countries, a French version of this questionnaire is needed. Such version will facilitate cross-linguistic comparisons of children’s DEAB.

The ChEAT is a language-simplified version of the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT [25, 26]), a self-reported questionnaire that assesses DEAB in adults and older adolescents. The most widely used version is the EAT-26 [26]; its 26 items can be summed up for a total score or divided in 3 subscale scores (“Dieting”, “Bulimia and Food Preoccupation”, and “Oral Control”). Both the EAT-26 and the ChEAT demonstrated good basic psychometric properties, making them useful screening tools for DEAB in general populations [16]. Mostly, previous validation studies of the ChEAT have reported good convergent validity with diverse measures of body image [4, 19,20,21]. However, the original 3-factor structure of the EAT-26 [26] have never been replicated with the ChEAT. Instead, most of the validation studies of the ChEAT proposed models with 4 to 6 factors, and some of them excluded items from the original 26-item version based on poor factor loading [27, 28]. Recently, Murphy et al.[29] reviewed 13 studies that included factorial analysis of the ChEAT and found no consistency among the proposed factorial structures. Therefore, they developed a new 5-factor structure keeping only the 14 items that fulfilled at least one of these 2 criteria: (1) in more than one third of the reviewed studies, the item loaded on the same factor with a factor loading > 0.70, or (2) in more than two thirds of the reviewed studies, the item loaded on the same factor with a factor loading > 0.30. They were the first to propose a short version of the ChEAT. The 5 factors they identified with their 14-item version were “Dieting”, “Weight preoccupation”, “Food preoccupation”, “Social pressure (to eat or to gain weight)” and “Vomiting (or purging)” with three items representing each subscale, except for the last factor, “Vomiting (or purging)”, that was only represented by two items. Using a large non-clinical sample of 13,674 boys and girls aged from 10 to 15 years old, they compared their 5-factor structure with the original 3-factor structure [26] and a single-factor structure. They found that their shorter (14-item) 5-factor version had a better fit than the original (26-item) 3-factor or the single-factor structure [29]. To provide support for the good convergent validity of their new version, Murphy et al. [29] demonstrated that their five-factor model could better explain adiposity than the three-factor or the single-factor model.

Murphy and colleagues’ shorter version of the ChEAT is of particular interest for screening DEAB in children, since this 14-item version is quicker to administer than the original 26-item version. However, considering that their sample was a mix of children and adolescents aged from 10 to 15 years old, it is impossible to determine with certainty whether this version is suitable for children only. The aim of the present study was to confirm the factorial structure proposed by Murphy et al. [29] and to examine the internal consistency of a French version of the 14-item ChEAT among a French-Canadian sample of children aged from 8 to 12 years old. A second aim was to test the measurement invariance by sex to determine whether the factorial structure applies to both boys and girls.

Methods

Participants

The sample consisted of 1092 children aged between 8 and 12 years old recruited from 27 public elementary schools located in two urban areas in the province of Quebec, Canada. Among participants, 468 were boys (43.1%) and 617 were girls (56.9%). Their mean age was 10.31 (SD = 1.18). Every body mass index (BMI) categories were represented: 5.3% of the children could be classified in the underweight category, 73.9% in the normal weight category, 16.3% in the overweight category and 4.5% in the obese category. Almost all of the children were born in Canada (95%) and came from a family where their parents were either married or living in a common-law relationship (83%). In general, children came from a wide range of social status, although most came from educated and well-off households. Nearly a third of the families had an annual family income of CAD $100,000 or more, and almost half of the children had a parent with a university degree.

Procedure

The children were invited to take part in a large study focusing on eating habits, body weight, and body image. They were informed of the study in class and received an envelope containing questionnaires on various themes related to eating and body image (many of them were not used in this study), and a consent form they could bring home to their parents. For those interested to participate, parental written consent was obtained. Children also provided written assent to participate. They had to complete questionnaires at home without the help of their parents, and to return the completed questionnaires to their teacher. Parents also had to complete questionnaires aside, including demographic information. Completion took approximatively 30 min for children and 45 min for parents. Height and weight were collected individually at school and out of sight of the children’s peers. Measures were took by trained research assistants. Children had to take off their shoes and to remove unnecessary clothes (e.g., hat, hoody, and coat). A metric scale and a numeric weighing scale were used, and height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight to the nearest 0.2 lb.

Measures

Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors (DEAB). The children’s version of the Eating Attitudes Test (ChEAT [15]) was adapted into French using standardized translation back-translation techniques [30]. Accordingly, an iterative process of independent forward- and back-translation was realized. Two independent professional translators were involved in the translation process. Moreover, an expert committee, including members of the research team and the translators, was formed to discuss any inconsistencies between the original and back-translated versions of the questionnaires until a consensus was obtained, as well as to supervise the process and make sure that the translated items were adequate and understandable by the participants. The ChEAT is a 26-item self-report questionnaire, measuring disordered eating attitudes and behaviors through a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always). Its reliability and concurrent validity have been demonstrated previously [4, 31]. In the present study, participants completed the original 26-item version, but only 14 items were retained for the present analyses, according to the 14-item version of Murphy et al. [29]. The items were scored following the original procedure [25]; the three lowest frequency choices (never to sometimes) were scored as 0, and the next three were scored 1 (often), 2 (very often), and 3 (always). The total score derived from the 14 items ranges from 0 to 42, with a higher score reflecting a higher presence and frequency of DEAB.

Body mass index (BMI). Height and weight were measured two times to ensure the validity of the measurement. The mean of the two measures was used to compute BMI (kg/m2). For weight, measurements in pounds were transformed into kilograms. The children’s BMI was classified into four categories (underweight, normal weight, overweight, or obese) according to childhood age- and sex-specific BMI cut-offs proposed by Cole et al. [32,33,34].

Statistical analysis

Group comparisons tests (t-test and ANOVA) were run to examine potential differences on ChEAT total score between sexes and BMI categories. Post Hoc comparisons with Bonferroni correction would be computed to target specific group differences in the case of a significant ANOVA. Confirmatory factorial analyses (CFAs) were performed with Mplus [35] using weighted least square mean and variance (WLSMV) adjusted estimators because normality could not be assumed. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML; maximum likelihood estimation under the missing at random assumption) was used to manage missing data. The sample size reached recommendations of 5–10 observations for each item included in a factor analysis [36]. To measure the fit of the model to the data, the following indices were used: Normed χ2 statistic (χ2/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). A χ2/df ratio of 3 or under, and a value over 0.90 for the CFI indicate an acceptable fit, whereas values of 0.08 and under are acceptable for the RMSEA indices [37, 38]. To test whether the model differed across sexes, measurement invariance with regard to sex was verified using multigroup tests. A first multigroup model was tested with all the factor loadings and intercepts allowed to load freely for both sexes, then a second multigroup model with the factor loadings constrained to be equal across sexes was tested, χ2 statistics of both multigroup model were then compared. To measure internal consistency, ordinal alpha was used to be consequent with the ordinal nature of the data [39, 40]. Ordinal alpha can be interpreted like Cronbach’s alpha, 0.70 being the acceptable lower bound [41].

Results

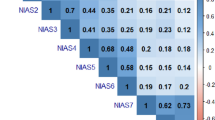

Descriptive statistics and group comparisons tests according to sex and BMI classification are presented in Table 1. Results showed that girls reported significantly higher scores on the ChEAT than boys, and that overweight and obese groups reported significantly higher scores than underweight and normal weight groups. Also, the obese group reported significantly higher scores than the overweight group. Frequency of responses for the 14 items of the ChEAT is presented in Fig. 1. The 5-factor structure with 14 items proposed by Murphy et al. [29] was first tested and revealed a poor fit to the data (normed χ2 (χ2/df) = 11.32; CFI = 0.866; RMSEA = 0.101, 90% CI(0.095 to 0.108)) because factor loadings for items 9 and 26 were very low due to the near absence of variance (only 10 out of 1092 participants did not score 0 on those items). Those two items, which represented the factor “Vomiting (or purging)”, were thus excluded. The analyses were re-conducted with the 12 remaining items and the structure that was tested was composed of the 4 remaining factors. This 4-factor structure with 12 items (henceforth called the ChEAT-12) provided a good fit to the data (normed χ2 (χ2/df) = 2.10; CFI = 0.987; RMSEA = 0.033, 90% CI (0.024 to 0.042)), with factor loadings ranging from 0.61 to 0.97 (see Table 2). Internal consistency of this 12-item version was good (α = 0.86), and each of the 4 subscales reached an acceptable level (α from 0.69 to 0.95; see Table 2). The four-factor structure was proved to be invariant across sexes as no difference were found between the multigroup model with all the factor loadings and intercepts allowed to load freely and the multigroup model with constrained factor loadings (χ2 = 9.61, p = 0.57).

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to confirm the factorial structure of a short version of the ChEAT, previously proposed by Murphy et al. [29], among a large sample of French-speaking children aged from 8 to 12 years old. Our results provided support for a 12-item version that is suitable for elementary school children.

In our non-clinical children population, most of the items of the ChEAT had a low but acceptable endorsement, excepted the items 9 (“I vomit after I have eaten”) and 26 (“I have the urge to vomit after meals”) that turned out to be irrelevant, because less than 1% of the sample endorsed them. Consequently, when computing the CFA, every item loaded properly on their respective factor except for items 9 and 26. After the removal of those items, a second CFA with the 12-item version provided a good fit for the data, which supported the removal of the 2 “vomiting (or purging)” items. Using the original version of the ChEAT, previous studies have reported similar issues with those items. For instance, many validation studies conducted among children samples excluded those two items, either because authors believed they were not suitable for children [19, 42] or because children uniformly scored zero [43, 44]. In their study, using a large community sample, Murphy et al. [29] reported only 4–5% of endorsement for those 2 items, but they kept them in their 14-item version because response frequency was high enough to estimate the parameters in their CFA. Although, we cannot exclude that other factors, linguistic or cultural, may be partly responsible for those difference, the most plausible explanation for this divergence between studies is that the sample of Murphy was older, with a sample ranging from 10 to 14 years old (Mage = 11.6). Indeed, vomiting and purging behaviors, in general, represent extreme behaviors for weight control that may reflect a degree of severity rarely observed in younger children. For instance, with a community sample of over 13,000 children aged from 9 to 14 years, 1-year incidence of purging was around 1% [45], while in a community sample of 5812 adolescents, around 7% reported purging behaviors at age 16 [46]. Taken together, these results support a 12-item version for elementary school children, without items referring to vomiting or purging behaviors, but did not invalidate the use of the 14-item version with adolescents.

This study allows to fill a gap in the present literature by providing a French short-version of the ChEAT that is suitable for children. First, neither the psychometric properties of the ChEAT nor any other DEAB screening tool in French had been previously validated. Therefore, there was no validated assessment for children’s DEAB that was available for French-speaking population. Currently, French is the 5th most spoken language on earth and it is the official language in 29 countries. This represents almost 300 million people and many children [47]. Second, even if a 26-item version of the ChEAT may already seem short, this questionnaire may most likely be used in a context where overall completion time is an issue (e.g., questionnaire battery, along with an interview). In a meta-analysis, the questionnaire length has been targeted as one factor that contributes to the response burden (i.e., the effort required by a person to answer a questionnaire) and that may raise the number of missing answers [48]. Therefore, reducing the questionnaire length and then, the response burden, may prevent methodological problems with children like missing data [48]. Completion time may even be more critical with children as their attentional capacities are more limited when they are under 13 years old [49]. Third, the sample of the current study included more than 1000 young boys and girls, and participants were distributed equally across sexes. Most of the previous validation studies did not include children under 10 or 12 years old, and some of them focused on girls only. In this study, girls showed a higher score of DEAB than boys, which is consistent with previous studies that explored sex differences in children of 10 years of age and up [50]. However, the measurement invariance showed that the factorial structure of the 12-item version did not differ across sexes. Therefore, although there is a difference in DEAB severity across sexes, boys and girls tend to endorse the same DEAB. Moreover, in order to provide a parsimonious tool while maintaining high validity, Murphy et al. [29] rigorous work was taken as a starting point. The fact that the 12-item version proposed in this study has already been validated among adolescents in the almost same version (except for the 2 “vomiting (or purging)” items), give further confidence in its validity. Finally, in this study, children classified in the overweight or obesity categories showed a higher severity of DEAB than those classified in the normal or underweight categories. Therefore, with the 12-item version, the DEAB severity difference between BMI classification observed in previous studies were replicated [51, 52].

The current study has limitations to consider. First, although the sample did offer an adequate representation of boys and girls, it would have been interesting to have more ethnic and socioeconomic diversity. Replication with diverse communities is very important as eating attitudes and behaviors may differ depending on cultural and socioeconomic background [53]. Similarly, the present sample was mostly composed of children without clinical eating or weight problems. Further validation on the 12-item version with a sample of children presenting with more severe DEAB, including children presenting an eating disorder or obesity, would be relevant. Second, other important psychometric properties like test–retest reliability were not examine with this French version and should thus be considered in future research. Third, for the moment, the French version of the ChEAT was proven to fit well a French-Canadian children sample, but the extent to which this factorial structure could be generalized to other French-speaking populations, or to other linguistic groups, remains to explore.

Conclusion

This study is the first to provide psychometric properties of a French assessment of DEAB in elementary school children. The French version of the ChEAT-12 represents a quick and reliable assessment for DEAB with non-clinical population and could be used as a screening tool with elementary school children, even though no cut-off is established yet. Early detection of attitudes and behaviors in regard to weight, shape, and eating is crucial because it can contribute to prevent the development of serious mental and physical health problems like eating disorders and obesity in adolescence.

What is already known on this subject?

-

The ChEAT is one of the most popular measuring tools for disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in children and a short version have been proposed.

What your study adds?

-

This study is the first to provide a French assessment of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in elementary school children and bring support for a short 12-item version.

References

Micali N, Hagberg KW, Petersen I, Treasure JL (2013) The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000–2009: findings from the general practice research database. BMJ open 3(5):e002646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002646

Volpe U, Tortorella A, Manchia M, Monteleone AM, Albert U, Monteleone P (2016) Eating disorders: what age at onset? Psychiatry Res 238:225–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.048

Nicholls DE, Lynn R, Viner RM (2011) Childhood eating disorders: British national surveillance study. Br J Psychiatry 198(4):295–301. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081356

Smolak L, Levine MP (1994) Psychometric properties of the Children’s eating attitudes test. Int J Eat Disord 16(3):275–282. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199411)16:3%3c275::AID-EAT2260160308%3e3.0.CO;2-U

Cohen DL, Petrie TA (2005) An examination of psychosocial correlates of disordered eating among undergraduate women. Sex Roles 52(1–2):29–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1191-x

Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Larson NI, Eisenberg ME, Loth K (2011) Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. J Am Diet Assoc 111(7):1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012

Sinton MM, Birch LL (2005) Weight status and psychosocial factors predict the emergence of dieting in preadolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord 38(4):346–354. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20176

Herle M, Stavola B, Hübel C, Abdulkadir M, Ferreira D, Loos R, Micali N (2020) A longitudinal study of eating behaviours in childhood and later eating disorder behaviours and diagnoses. Br J Psychiatry 216(2):113–119. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.174

Wade KH, Kramer MS, Oken E, Timpson NJ, Skugarevsky O, Patel R, Martin RM (2017) Prospective associations between problematic eating attitudes in midchildhoodand the future onset of adolescent obesity and high blood pressure. Am J Clin Nutr 105(2):306–312. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.141697

Micali N, House J (2011) Assessment measures for child and adolescent eating disorders: a review. Child Adolesc Mental Health 16(2):122–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2010.00579.x

Decaluwé V, Braet C (2004) Assessment of eating disorder psychopathology in obese children and adolescents: interview versus self-report questionnaire. Behav Res Ther 42(7):799–811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2003.07.008

Hilbert A, Hartmann AS, Czaja J (2008) Child eating disorder examination-questionnaire: evaluation der deutschsprachigen Version des Essstörungsfragebogens für Kinder [Evaluation of the German-speaking version of the child eating disorder examination questionnaire]. Klin Diagn Eval 1:447–463

Eklund K, Paavonen EJ, Almqvist F (2005) Factor structure of the eating disorder inventory-C. Int J Eat Disord 37(4):330–341. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20097

Garner DM (1991) Eating disorders inventory-C. Psychological Assessment Resources, Lutz

Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, Daniels SR (1988) Reliability testing of a children’s version of the eating attitudes test. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27(5):541–543. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-198809000-00004

Nathan JS, Allison DB (1998) Psychological and physical assessment of persons with eating disorders. In: Hoek H, Treasure J, Katzman M (eds) Neurobiology in the treatment of eating disorders. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, pp 47–96

Erickson SJ, Gerstle M (2007) Developmental considerations in measuring children’s disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eat Behav 8(2):224–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.06.003

Rojo-Moreno L, García-Miralles I, Plumed J, Barberá M, Morales MM, Ruiz E, Livianos L (2011) Children’s eating attitudes test: validation in a sample of Spanish schoolchildren. Int J Eat Disord 44(6):540–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20855

Sancho C, Asorey O, Arija V, Canals J (2005) Psychometric characteristics of the Children’s eating attitudes test in a Spanish sample. Eur Eat Disord Rev 13(5):338–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.643

Teixeira MCB, Pereira ATF, Saraiva JMT, Marques M, Soares MJ, Bos SC, Macedo AF (2012) Portuguese validation of the children’s eating attitudes test. Revista de Psiquiatria Clinica 39(6):189–193. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832012000600002

Theuwis L, Moens E, Braet C (2010) Psychometric quality of the Dutch version of the children’s eating attitude test in a community sample and a sample of overweight youngsters. Psychol Belg 49(4):311–330. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb-49-4-311

Chiba H, Nagamitsu S, Sakurai R, Mukai T, Shintou H, Koyanagi K, Matsuishi T (2016) Children’s eating attitudes test: reliability and validation in Japanese adolescents. Eat Behav 23:120–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.09.001

Edlund B, Hallqvist G, Sjödén PO (1994) Attitudes to food, eating and dieting behaviour in 11 and 14-year-old Swedish children. Acta Paediatr 83:572–577. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13084.x

Lommi S, Viljakainen HT, Weiderpass E, de Oliveira Figueiredo RA (2020) Children’s eating attitudes test (ChEAT): a validation study in Finnish children. Eating Weight Disord 25:961–971. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00712-w

Garner DM, Garfinkel PE (1979) The eating attitudes test: an index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychol Med 9(2):273–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700030762

Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE (1982) The eating attitudes test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 12(4):871–878. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291700049163Harrison,2009

Anton SD, Han H, Newton RL Jr, Martin CK, York-Crowe E, Stewart TM, Williamson DA (2006) Reformulation of the Children’s eating attitudes test (ChEAT): factor structure and scoring method in a non-clinical population. Eat Weight Disord 11(4):201–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327572

Lynch WC, Eppers-Reynolds K (2005) Children’s eating attitudes test: revised factor structure for adolescent girls. Eating Weight Disord 10:222–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03327489

Murphy TJ, Hwang H, Kramer MS, Martin RM, Oken E, Yang S (2019) Assessment of eating attitudes and dieting behaviors in healthy children: confirmatory factor analysis of the Children’s eating attitudes test. Int J Eat Disord 52:669–680. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23062

Hambleton RK (2005) Issues, designs, and technical guidelines for adapting tests to languages and cultures. In: Hambleton RK, Merenda P, Spielberger C (eds) Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 3–38

Maloney MJ, McGuire JB, Daniels SR, Specker B (1989) Dieting behavior and eating attitudes in children. Pediatrics 84(3):482–489

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. Br Med J. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240

Cole TJ, Flegal KM, Nicholls D, Jackson AA (2007) Body mass index cut offs to define thinness in children and adolescents: international survey. Br Med J. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39238.399444.55

Cole TJ, Lobstein T (2012) Extended international (IOTF) body mass index cut-offs for thinness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes 7(4):284–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2012) Mplus: the comprehensive modelling program for applied researchers: user’s guide, 7th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Arrindell WA, van der Ende J (1985) An empirical test of the utility of the observations-to-variables ratio in factor and components analysis. Appl Psychol Meas 9(2):165–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900205

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS (2001) Using multivariate statistics, 4th edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Zumbo BD (2012) Estimating ordinal reliability for Likert-type and ordinal item response data: a conceptual, empirical, and practical guide. Pract Assess Res Eval 17(3):1–13. https://doi.org/10.7275/n560-j767

Zumbo BD, Gadermann AM, Zeisser C (2007) Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for likert rating scales. J Mod Appl Stat Methods 6(1):21–29. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1177992180

Nunnally JC, Bernstein IH (1994) Psychometric theory, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New-York

Senra C, Seoane G, Vilas V, Sánchez-Cao E (2007) Comparison of 10- to 12-year-old boys and girls using a Spanish version of the children’s eating attitudes test. Personal Individ Differ 42(6):947–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.005

Elizathe LS, Murawski B, Arana FG, Rutsztein G (2012) Propiedades Psicométricas del Children’s eating attitudes test (ChEAT): Unaescala de identificación de riesgo de trastornos alimentarios en niños. Revista Evaluar 11(1):18–39. https://doi.org/10.35670/1667-4545.v11.n1.2840

Pilecki MW, Kowal M, Woronkowicz A, Kryst Ł, Sobiecki J (2013) Psychometric properties of polish version of the children’s eating attitudes test. Arch Psychiatry Psychother 15(1):35–43

Haines J, Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman S, Field AE, Austin SB (2010) Family dinner and disordered eating behaviors in a large cohort of adolescents. Eat Disord 18(1):10–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260903439516

Brown M, Hochman A, Micali N (2020) Emotional instability as a trait risk factor for eating disorder behaviors in adolescents: sex differences in a large-scale prospective study. Psychol Med 50(11):1783–1794. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719001818

Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) (2019) La langue française dans le monde. http://observatoire.francophonie.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Edition-2019-La-langue-francaise-dans-le-monde_VF-2020-.pdf

Rolstad S, Adler J, Rydén A (2011) Response burden and questionnaire length: is shorter better? A review and meta-analysis. Value Health 14(8):1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.003

Weber AM, Segalowitz SJ (1990) A measure of children’s attentional capacity. Dev Neuropsychol 6(1):13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/87565649009540446

Ricciardelli LA, McCabe MP (2001) Children’s body image concerns and eating disturbance. Clin Psychol Rev 21(3):325–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00051-3

Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ (2000) Weight-related behaviors among adolescent girls and boys: results from a national survey. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 154(6):569–577. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.154.6.569

Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA (2004) Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol 72(1):53–61. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53

Cheng ZH, Perko VL, Fuller-Marashi L, Gau JM, Stice E (2019) Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eat Behav 32:23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.11.004

Acknowledgements

We thank Hélène Paradis for statistical analysis guidance. This study was funded by Fonds de Recherche du Québec, Santé.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. Maxime Legendre received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research during this study. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of Canada and received approval from the university’s institutional review board.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This research involved human participants.

Informed consent

Every participant provided informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Legendre, M., Côté, M., Aimé, A. et al. The children’s eating attitudes test: French validation of a short version. Eat Weight Disord 26, 2749–2756 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01158-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-021-01158-9