Abstract

Background

Internalized sociocultural standards of attractiveness are a risk factor repeatedly linked to eating disorders; however, many nonbinary individuals do not conform to these standards.

Purpose

This study investigated the body checking behaviors and eating disorder pathology among nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals.

Methods

Participants (n = 194) completed an online survey assessing body checking behaviors, body appreciation, gender congruence, and eating disorder pathology

Results

Body checking predicted eating disorder pathology, and body image significantly improved the model. Gender congruence did not additional variance in predicting eating pathology

Conclusion

Though gender congruence was not a significant predictor of eating pathology, content analysis revealed unique body behaviors specific to nonbinary individuals’ gender identity and gender expression. Clinical implications include expanding perceptions of eating disorder presentation when working with nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross-sectional descriptive study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The purpose of the current study is to investigate body checking behaviors and the relationship between body checking behaviors and eating disorder pathology in nonbinary individuals. Cisgender refers to an individual who feels as though their gender identity aligns with their sex assigned at birth. Nonbinary is a heterogenous gender identity in which an individual may identify with male and female, neither male or female, or outside of the gender binary [1]. While research on disordered eating, body image, and body checking behaviors has largely been conducted with cisgender heterosexual samples [2], gender minorities are at increased risk for eating and body image concerns as compared to cisgender individuals [2, 3]. Sociocultural standards of attractiveness have been consistently found as a risk factor for disordered eating and body image concerns [4]. These norms center cisgender heterosexual women, and the same standards have been imposed on gender minorities. However, because gender minorities do not adhere to the same standards [5,6,7], this bias has serious diagnostic and treatment implications. The traditional design in studying behaviors in marginalized populations compares individuals to a “normative sample;” this approach fails to capture the heterogeneity of body image concerns expressed within individuals who are gender expansive [3, 8].

As body checking behaviors are a central symptom across eating disorders and may serve to maintain other eating disorder symptoms [9, 10], insight into these behaviors could provide clinical utility. Specific types of body checking behavior differ by gender [11], but little is known about body checking behaviors among nonbinary individuals. Gender differences in body checking behaviors may be partially explained by varying body image ideals among individuals of different genders [12]. For instance, men tend to evaluate their muscularity, whereas women tend to evaluate their thinness [13]. Because nonbinary individuals are less likely to conform to binary gender standards [5, 13], they may check different aspects of their bodies and for different reasons than cisgender individuals. Body checking behaviors may be accompanied by safety beliefs, such as checking their bodies help them avoid consequences of not checking (e.g., weight gain) [14]; for gender minorities, consequences may relate to concealment or social reading [6, 15]. Though gender expression and transgressing sociocultural appearance norms may be experienced positively, individuals who do not conform to cisgender heteronormative standards of attractiveness are more likely to be victims of sexual and gender prejudice [16]; therefore, gender minorities may body check to avoid violence and manage gender dysphoria.

Body image and eating disorders in gender minority individuals

Body image among gender minorities has typically been studied through the minority stress model, which posits that individuals with marginalized identities are at heightened risk to suffer from mental disorders because of gender-based prejudice [17]. Although not all trans individuals are dissatisfied with their bodies, current findings with binary trans individuals suggest that trans individuals are more dissatisfied with their bodies than cisgender individuals [18] and are at increased risk for eating disorders than cisgender individuals [18, 19]. Among binary trans individuals, eating disorder symptoms typically align with one’s gender identity [3, 8, 20]. For instance, a drive for thinness has been reported in both trans-feminine and trans-masculine individuals to suppress physical characteristics associated with their assigned sex [21] and minimize visible dissonance [22]. However, the motivation behind the drive for thinness differs across gender, where trans men intend to reduce curves while trans women intend to accentuate gender through thinness [23, 24]. Although trans individuals, overall, have a high proneness for developing an eating disorder [25], trans men are at a greater risk than are trans women [26]. This could be because trans women’s body dissatisfaction is more likely to center on genitalia [22] which are not altered by eating disorder symptoms or behaviors. In addition, trans men engage in more body checking behaviors than trans women [26]. Qualitative studies reveal that trans individuals’ gender identity relate to their symptom presentation, as their eating disorder symptoms may serve to reduce gender dysphoria [21, 27,28,29]. Another factor that related to identity that may influence eating disorder pathology is minority stress. Indeed, minority stress is related to more disordered eating behaviors and body image concerns [15, 30]. Gender dysphoria may underlie this risk [31], but gender dysphoria is likely rooted in society’s perceptions of trans individuals’ gender and body, thus secondary to the traditional and current understanding of eating disorder pathology and emotion regulation [25].

There is a paucity of research investigating body image and eating disorders in trans individuals who identify as nonbinary. Only two known studies have been published on this topic and with conflicting evidence, with one study suggesting nonbinary individuals may experience greater body image satisfaction than trans individuals who identify with the binary [32] and another finding no significant difference in body image between groups [33]. This discrepancy could be explained by the use of different measures to assess body satisfaction. Differences in body satisfaction were found using the Hamburg Body Drawing Scale [34] (a more visual measure) while no such differences were found with the Body Investment Scale [35] (a more affective and behavioral measure). This is consistent with the fact that nonbinary individuals report less satisfaction with aspects of their body that are salient for social recognition (e.g., hairstyles, clothes) [32]. Because of the sources of body image dissatisfaction may differ between nonbinary and binary trans individuals, body checking in nonbinary individuals may be targeted toward mannerisms or dress, rather than their physical bodies.

Nonbinary individuals may have expansive forms of gender expression [36, 37]. Mason et al. proposed an integrative model for understanding disordered eating among sexual minorities that acknowledges the role of gender experiences (i.e. gender expression and sexual objectification), sexual orientation experiences (minority stress), and their interaction in relation to disordered eating [38]. Though this model was proposed for sexual minority women, it may usefully apply to gender minorities given their experiences with minority stress and varying gender expression. Recent studies with sexual minority women have challenged binary notions of gender expression with the surfacing of an androgynous or “boyish” ideal [39,40,41]. Trans and nonbinary individuals may also adopt an androgynous gender expression [5, 42]. Some nonbinary individuals may achieve androgyny through minimizing certain body parts and accentuating others [42], or by embodying a balanced aesthetic of femininity and masculinity [5, 6, 42]. These findings highlight the need for a culturally responsive lens Mason et al. advocate in understanding gender identity in relation with eating disorder pathology [38].

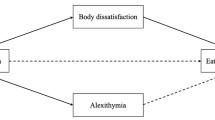

This study used a mixed-method approach to investigate body checking behaviors among nonbinary individuals whose appearance ideals are outside of traditional standards of attractiveness. Quantitative measures allowed us to use inferential statistics to assess the relation between body checking, body image, and eating disorder pathology. Qualitative methods allowed us to explore if there are body checking behaviors unique to nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals. Authors hypothesized that: (H1) higher body checking behaviors will predict increased eating pathology; (H2) body appreciation will moderate the effect of body checking on eating pathology; and (H3) gender congruence will uniquely contribute to the variance of body checking behavior on eating disorder pathology for nonbinary participants with androgynous appearance ideals. Finally, as the current measurement lacks gender inclusivity, some body checking behaviors may not be captured in the Body Checking Questionnaire [43]. This was explored through an open-ended question for participants to describe other checking behaviors they engage in to monitor their bodies.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 194 nonbinary adults (n = 122 assigned female; n = 61 assigned male; n = 4 assigned intersex; and n = 7 who chose not to respond) who endorsed androgynous or non-stereotypical body ideal. Participants identified as agender (n = 20), bigender (n = 1), gender queer/fluid (n = 32), and nonbinary (n = 141). Most participants were between the ages 18 and 24 (63.40%) and identified their racial/ethnic identity as White (78.87%), and 21.12% of individuals reported a racial/ethnic minority identity. See Table 1 for complete demographic data.

Procedure

After institutional review board approval was obtained, participants were recruited primarily through social networking sites and online forums centered on sexual orientation and gender identity. Participants were asked to complete an online survey studying body image of individuals with androgynous or non-stereotypical appearance ideals. Individuals were informed that their participation was completely voluntary, their answers would remain anonymous, and they could opt out of any questions they did not wish to answer. The survey took about 30 min to complete, and upon completion, participants were provided space to leave feedback on their experience and/or how authors can be more inclusive.

Measures

Body checking

The Body Checking Questionnaire (BCQ) is a 23-item measure used to assess body checking behaviors on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) [43]. Higher scores indicate more body checking behaviors. The BCQ yields a global score and three subscale scores: overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic checking. A sample item for overall appearance subscale is “I check my reflection in glass doors or car windows to see how I look.” An example item for specific body parts is “I pinch my stomach to measure fatness.” “I check the diameter of my wrist to make sure it’s the same size as before” is a sample item for the idiosyncratic subscale. Reas et al. [43] reported internal consistency with alpha coefficients of 0.88, 0.92, and 0.83 for overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic checking, respectively. The BCQ total score indicated test–retest reliability [43]. Cronbach’s alpha for the BCQ total score was 0.93 for the sample. Alpha coefficients of 0.81, 0.90, and 0.79 were found for overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic checking, respectively.

Several of the items loading onto specific body parts pertain to thighs or stomach, e.g. “I check to see if my thighs spread when I’m sitting down”, and items that load onto the overall appearance factor center around fatness, e.g. “I try to elicit comments from others about how fat I am.” This may ignore areas of concern for gender minorities who might place more emphasis on their chest or curvature [22]. Because of this, a qualitative question was posed to capture body checking behaviors not measured by the BCQ: Are there any behaviors not listed above that you engage in to check your appearance, size, and/or shape? If yes, please explain. Please do not include any identifying information in your response.

Body image

The Body Appreciation Scale (BAS) is a positive measure of body image comprised of 10 items [44]. The BAS measures an individuals’ acceptance of and respect for their body with high internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s coefficient alpha = 0.93) and construct validity [44]. Participants rated their body appreciation on a Likert-scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Always), where higher scores reflect a more positive body image. Example items include “I am comfortable in my body” and “I feel beautiful even if I am different from media images of attractive people (e.g., models, actresses/actors).” A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.95 was found for the current study.

Eating disorder pathology

The Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire (EDE-Q) [45] is a 28-item self-report measure of eating disorder psychopathology adapted from the interview assessment Eating Disorder Examination [46]. The EDE-Q provides an overall eating disorder pathology score and four subfactors: Restraint, Weight Concern, Shape Concern, and Eating Concern. Participants responded to questions measuring pathology over the past 28 days on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (No days) to 6 (Every day). Higher scores indicate higher pathology and symptomatology. An example item is “Have you been deliberately trying to limit the amount of food you eat to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)?” The EDE-Q has strong internal consistency [47]; for the present study, alpha coefficients of 0.88, 0.91, 0.86 0.88 were found for Restraint, Shape, Weight, and Eating Concern subscales, respectively.

Gender congruence

Gender congruence refers to feeling in harmony with one’s gender and was measured using 17 items from the gender congruence cluster composed of four factors (genitalia, chest, other secondary sex characteristics, and social role recognition) from the Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS) [48]. Participants responded to items using a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Always) to 5 (Never). Higher scores indicate more gender congruence. An example item for gender congruence is “I have felt comfortable with how other people perceive my gender based on my physical appearance.” For the present study, gender congruence was found reliable with an alpha coefficient of 0.77.

Data analysis

Power analysis calculated in G×Power 3.1 indicated that 55 participants would be needed to achieve statistical significance (p < 0.05) and to see a medium effect size of f2 = 0.15 with 80% power for a linear multiple regression fixed model R2 increase with five predictor variables on one degree of freedom. To test the first hypothesis of whether body checking predicts eating disorder pathology, a simple linear regression was performed. To test the second and third hypotheses, body image and gender congruence were added in Step 2 and Step 3, respectively, to assess if they uniquely predicted the variance of eating disorder pathology for nonbinary participants. Participants with less than 90% complete data were removed.

Qualitative responses were coded via content analysis [49] to identify body checking behaviors not captured in the BCQ that participants used to monitor their appearance. After reading participants’ qualitative descriptions, the first and second authors discussed the data and developed a coding scheme. Authors then independently coded the data and achieved a 93.71% agreement. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion.

Results

Prior to conducting primary analyses, bivariate correlations were examined (Table 2). There was a strong, positive relationship between BCQ and EDE-Q (r = 0.85, p < 0.001). BAS was negatively associated with BCQ (r = − 0.49, p < 0.001) and EDE-Q scores (r = − 0.56, p = 0.005). GCLS scores were positively related to BCQ (r = 0.35, p = 0.002) and EDE-Q (r = 0.41, p = 0.005).

Predictors of eating disorder pathology

A simple linear regression showed that participants who reported higher scores on the BCQ were more likely to report higher scores on the EDE-Q, t(83) = 14.25, p < 0.001, ß = 0.85, explaining 71.12% of the variance in EDE-Q scores. Specifically, for each additional increase in BCQ score, the model predicted that EDE-Q score would increase 0.07 points. Thus, H1 was confirmed. To test H2, BAS scores were added to the model in Step 2, demonstrating significant improvement ∆F(2,79) = 4.49, p = 0.014, such that Model 2 explained 73.42% of the variance in EDE-Q scores (∆R2 = 2.91%). As shown in Table 3, BCQ scores (ß = 0.06) and BAS scores (ß = − 0.33) were predictors of EDE-Q scores, but the interaction term was not significant (ß = − 0.01).

To address H3, we tested whether GCLS scores added variance in predicting EDE-Q scores, after accounting for the relationship between BCQ and BAS. GCLS was added in Step 3, and though the overall model was significant, F(7,75) = 33.05, R2 = 73.23%, p < 0.001, GCLS scores did not predict EDE-Q scores (ß = 0.06). Moreover, adding GCLS did not significantly improve the model, ∆F(4,75) = 0.86, ∆R2 = 1.13%, p = 0.450, so Model 2 was upheld.

A visual inspection of residuals revealed homoscedasticity, as residuals were relatively evenly spread, and linearity, as indicated by the fact that the residuals did not show a curved pattern. K–S tests were performed on each model and confirmed normality (ps > 0.09) A Mahalanobis test identified three outliers, which were removed. This did not change the pattern, and the overall relationship of Model 2. BCQ, t = 9.86, ß = 0.73, p < 0.001, and BAS, t = − 2.57, ß = − 0.18, p = 0.012, scores remained significant predictors of EDE-Q scores, and the interaction between the two were not significant, t = − 0.81, ß = − 0.05, p = 0.421.

Qualitative descriptions of body checking behaviors

After taking the BCQ, participants completed an open-ended question inquiring of other body checking behaviors in which they engage that were not reflected in the BCQ. The final coding structure was developed from responses (n = 89) to the open-ended prompt asking if there were other body checking behaviors in which they engaged. The coding scheme included three broad categories: (1) traditional body checking behaviors (overall appearance, specific body parts, idiosyncratic checking), (2) gender-specific body checking behaviors (dysphoria, external modifications, androgynous aesthetic), and (3) behaviors beyond checking for thinness (body appreciation, muscularity, outside of thinness). Themes are not mutually exclusive as individual responses could be coded as exemplifying more than one theme. As an example, one participant stated, “I often press down or manipulate my chest to try and imagine what it would look like if it was not there” (White, nonbinary). This response was coded both as specific body parts and dysphoria. Quotes are contextualized with the participants’ racial/ethnic and gender identities.

Traditional body checking behaviors

When asked about body checking behaviors that were not captured in the BCQ, 85.25% participants reported behaviors that did not specifically match the items; however, these behaviors aligned with concepts that the BCQ assesses through its three subscales (overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic checking). Traditional body checking behaviors refer to these subscales. Thirty-four percent of participants’ checking behaviors concerned overall appearance. For example, one participant stated that they “take body pictures in mirrors and take selfies and compare to older pictures of myself” (White, genderqueer). Another participant shared that they “look at [their] body from different angles in the mirror to see if [their] silhouette has changed” (White, nonbinary, bisexual). Twenty-four percent of participants engaged in behaviors that were related to specific body parts. For instance, one participant checked their body by “draw[ing] on the mirror in dry erase marker to see if [their] stomach, butt, or legs are larger or smaller” (White, agender). Twenty-six percent of participants reported idiosyncratic checking behaviors similar to items on the BCQ [43], such as “squeez[ing] my hands around my waist hoping to measure how far my fingers are from touching” (White, nonbinary) and “lying on the floor to see if you’re thicker than the pencil belly button test” (Hispanic/Latinx, genderqueer).

Gender-specific body checking behaviors

Thirty-one percent of participants endorsed gender specific body checking behaviors, 18.03% noting experiences with dysphoria. Participants checked to see if their body matched their ideal, which motivated some to engage in behaviors to achieve gender congruence. For instance, one participant responded, “I draw hair on my arms and chest with makeup” (White, nonbinary). Another participant shared that they “stare at [their] face in the mirror and think for far too long about whether or not [they] are okay with it and wonder if other people notice [they] have a tiny mustache” (White, genderqueer). Six participants reported actions involving external modifications, such as chest binders. These responses were often coded under the dysphoria category as well. For example, a participant reported, “I'll constantly check reflections to see if my binder has flattened me enough, and adjust my shirt to give myself a flatter appearance” (Hispanic/Latinx, nonbinary). One participant noted packing, which was also coded as an external modification. They indicated “I use packers (or socks, or my hands) in the mirror to visualize my body with a penis, and to check the fit of pants meant for penis owners” (White, genderqueer). Ten participants engaged in body checking to evaluate an androgynous aesthetic.

I look at how much do clothes accentuate the narrowness of my shoulders and the wideness of my hips (if they do it too much I usually don’t wear them). I don’t wear clothing that accentuates or makes my breasts look bigger. (White, agender).

Body checking behaviors beyond thinness

Lastly, we coded responses that reflected checking behaviors that question the assumption of thinness. About 30% of participants’ body checking behaviors were explicitly not related to thinness. Three subcategories that comprised the larger idea of questioning thinness included body appreciation, muscularity, and outside of thinness. Seven participants noted they engaged in body checking behaviors to see parts they like and accept about their bodies. One participant stated that when they look at their body it is “not me scrutinizing my body and wishing it were different but positively appreciating it and not wanting it to change” (White, nonbinary). Another participant noted that they do look at themselves in reflective surfaces so they “can constantly check [themselves] out” (Hispanic/Latinx, nonbinary). Twenty-two participants engaged in body checking behaviors to evaluate their muscularity, such as flexing, looking at the shape of abs in the mirror, and tracking muscle tone. A participant reported that they “flex arm muscles in the mirror, flex my arms to look at the definition in my shoulder muscles, try to elicit comments from others about how strong I look, compare my athletic form to others in classes and group settings” (White, nonbinary). Seven participants endorsed checking behaviors that suggested they were checking their bodies beyond a thin or muscular ideal, and some stated that they like being chubby. A participant commented “I’m thin, so I inflate and move around my cheeks to see how I would look more fat” (Hispanic/Latinx, agender).

Discussion

The mixed-method approach to investigating body checking behaviors and eating disorder pathology extend the literature to understand factors unique to individuals who do not adhere to sociocultural standards of attractiveness. These findings demonstrate that the BCQ is an adequate measure of body checking for nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals. Specifically, the three subscales may be useful for understanding different types of checking behaviors when working the nonbinary individuals experiencing body image and eating concerns. The present findings, however, further suggest a point of caution. While it is possible that eating disorder pathology drives the body checking behavior beyond gender minority stress, not everyone has a thin ideal. Even though nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals may be able to complete the BCQ, these qualitative data reveal that existing measures may not be capturing the whole of their experiences, specifically as it relates to their gender identity and androgynous ideal.

Predictors of eating disorder pathology for nonbinary individuals

As expected, body checking behaviors predicted eating disorder pathology. However, this relation did not depend on body image. This was surprising because of previous literature correlating body checking behaviors and body image [50]. Though the BAS may be considered a “positive” measure of body image, body appreciation and negative body evaluation may be related yet independent constructs. However, Walker et al.’s meta-analysis [50] included studies with presumably cisgender and heterosexual participants. The present research suggests that the relation between body image and body checking is different for individuals with androgynous gender expressions. A possible explanation as to why body image did not moderate the relationship between body checking and eating disorder pathology is body image may stem from these androgynous gender expressions, such that thinness may be less important to nonbinary individuals than it is for cisgender heterosexual individuals. This could serve as evidence that body image satisfaction and gender dysphoria are distinct constructs, which may not be driven from the same latent entities as eating disorder pathology [8]. This was further bolstered by the third hypothesis not being supported. After accounting for body checking and body appreciation, gender congruence did not add variance in predicting eating disorder pathology reported by nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals. Even though gender congruence did not predict eating disorder pathology, it is worthwhile to note that it was moderately and positively related to both body checking and eating disorder pathology. While the purpose of this study focused on overall eating disorder pathology, it is possible that gender congruence did not explain additional variance of eating disorder pathology because factors such as Eating Concern and Weight may be less salient than Shape Concerns [51]. Additionally, in this community sample, most of the participants were below the cutoff point of 2.2 [52] and similar to community norms evidenced in binary transgender individuals [51]. In regard to body checking, it is possible that if one experiences more gender congruence, they may be more likely to check their bodies in order to maintain feelings of gender congruence and avoid minority stress, such as internalized shame and transphobia. For similar reasons, one then may endorse eating disorder pathology in order to manage one’s dysphoria. These speculations are consistent with literature that posits body checking behaviors serve as a protective strategy to avoid consequences of not checking [14]. As gender dysphoria is a proximal factor of minority stress [53], eating pathology may serve as an avoidant coping skill of minority stress. Though there is evidence that the EDE-Q is a valid measure of eating disorder pathology for transgender individuals, future studies should examine its use in a nonbinary sample.

Body checking behaviors beyond the BCQ

The quantitative data suggest that body checking was a relatively common experience, and the qualitative data reveal that nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals may uniquely engage in body checking behaviors not captured in the BCQ. Thus, it is necessary to explore checking behavior as it relates to pertinent factors unique to their gender identities and expression, such as gender dysphoria and androgynous aesthetic. These behaviors may not be rooted in a drive for thinness, and they may present as external modifications related to secondary sex characteristics and body shape. Body checking was strongly, positively correlated with eating disorder pathology and negatively correlated with body appreciation. Body checking may influence the maintenance of body dissatisfaction [43]. Underlying the BCQ is the assumption of the drive for thinness. This makes sense given that the drive for thinness is a risk and maintenance factor related to eating disorder behaviors [54, 55].

Participants described body checking actions that were not specifically measured in the BCQ, but that could reasonably be mapped onto the existing factor structure related to overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic behaviors. For instance, participants described checking waist size, checking for bones, checking muscles, and taking selfies to compare photos. However, eating disorder pathology is likely more complex than a drive for thinness, as evidenced by the increased attention to the drive for muscularity in men [56, 57]. Participants also described checking behaviors that were characterized as gender specific. Clothes, hiding shape, and checking chest were common experiences for the present sample. For some participants, checking curves was not necessarily about dissatisfaction with fat but instead reflected a dissatisfaction with being read feminine. Individual checking behaviors included external modifications such as chest binding and wearing packers. Some of the behaviors were framed as assessing overall aesthetic in balancing femininity and masculinity. This was typically described with behaviors related to evaluating shape, which described checking in order to reduce curves to achieve flatness and/or a stereotypical muscular appearance with larger shoulders and narrow hips. These data support Mason et al.’s call for an integrative model contextualizing body image and eating disorder pathology with experiences of gender and sexual orientation experiences [38].

Not all body checking behaviors were indicative of body image dissatisfaction or eating disorder pathology. Some participants described checking their body served as a means of appreciating their body or as a neutral appraisal of their body. These participants question the assumption of thinness on which the BCQ focuses. Previous work has found gender differences in drive for thinness, where women endorse higher levels than men [54, 55]. These findings rest on the assumption that gender identity aligns with gender expression. However, given that gender identity and gender expression may have a fluid nature [58], they do not always map onto binary understandings of gender identity, expression, and roles. These qualitative findings suggest that nonbinary individuals with androgynous body ideals may not experience a drive for thinness.

Limitations and future directions

It is necessary to view the results in the context of their limitations. Online convenience sampling allowed us to collect data from nonbinary individuals, who are largely understudied in the literature. The findings advance the eating disorder and body image fields’ understandings of body checking and eating disorder pathology of individuals typically excluded from studies or analyzed with binary trans samples. However, this sample reflected the pitfalls of online convenience sampling in that our sample was predominantly White and young [59]. Moreover, findings from a community sample may not apply to those with clinical eating disorders, which could explain why gender congruence did not predict eating disorder pathology. As most of the participants in the current study did not report clinical eating disorder pathology, future research should consider whether the present findings can be generalized meaningfully to a clinical population.

Directions for future research and clinical implications

As body checking is a central symptom across eating disorders [9], an updated body checking scale may be necessary in order to be both gender inclusive and to reflect advancements in technology. Additionally, muscularity is an increasing concern for men, and these data suggest muscularity is salient for nonbinary individuals as well. Body checking items that reflect the cognitions and affect in the Drive for Muscularity Scale [60] may be a start in capturing checking behaviors that are outside of a drive for thinness but still related to eating disorder pathology. Overall appearance, specific body parts, and idiosyncratic checking are salient for nonbinary individuals, but the qualitative findings show the specifics may differ both in terms of motivation (driven by gender-related factors) and expression (external modifications and androgynous aesthetic). As most of the existing eating disorder measures have been developed and normed with cisgender heterosexual women’s experiences [61], it is insufficient to study the experiences of nonbinary individuals with these measures without noting their shortcomings [62]. Updating the BCQ may be necessary to capture the heterogeneity of body checking behaviors among nonbinary folks.

The present study found gender congruence was not a significant predictor of eating disorder pathology for nonbinary individuals. Because gender dysphoria is not a fixed state [42, 63], future work could assess gender congruence and gender dysphoria over time to see whether fluctuations in minority stress broadly, as well as gender dysphoria specifically, predict eating disorder symptoms. Previous studies using EMA revealed that changes in eating disorder behaviors may change with mood [64] and behaviors may then influence eating disorder cognitions [65]. Thus, for gender minorities, it will be important to assess how experiencing gender-related stressors, as opposed to negative mood, relates to eating disorder behaviors in the real world.

For clinicians working with nonbinary individuals on body image or eating concerns, it is essential to explore gender identity as a contextual factor. Previous qualitative work has revealed that an androgynous body ideal is central to nonbinary individuals’ gender identity and that they may manage their dysphoria through changing their appearance via clothes and exercise [42, 63]. The present findings extend this literature by studying gender identity and androgyny specific to eating disorder pathology. Though gender congruence was not a significant predictor of eating disorder pathology, the qualitative results suggest that some individuals engage in body checking behaviors that are specific to their gender identity and/or gender expression. It is important that clinicians go beyond assumptions of thinness and view gender identity, gender expression, and eating disorder symptoms collectively [38]. Body image and body dysphoria are distinct but related constructs [8]. This stresses the necessity for health care providers to understand symptoms in the context of gender identity rather than impose gender binary ideas of thinness, which may not apply or may be experienced differently, on nonbinary folks with androgynous appearance ideals.

What is already known on this subject

Body checking is a central maintenance symptom of eating pathology associated with poor body image; however, this body image centers cisgender women, failing to account for nonbinary individuals.

What this study adds

This study reveals body checking behaviors for nonbinary individuals. Clinicians should explore eating pathology in context of gender specific factors (e.g., gender dysphoria and gender expression).

Data availability

Email corresponding author Dr. Paz Galupo, pgalupo@towson.edu.

References

Matsuno E, Budge SL (2017) Non-binary/genderqueer identities: a critical review of the literature. Curr Sex Health Rep 9:116–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8

Diemer EW, Grant JD, Munn-Chernoff MA, Patterson DA, Duncan AE (2015) Gender identity, sexual orientation, and eating-related pathology in a national sample of college students. J Adolesc Health 57:144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003

Jones BA, Haycraft E, Murjan S, Arcelus J (2016) Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in trans people: a systematic review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry 28:81–94. https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2015.1089217

Izydorczyk B, Sitnik-Warchulska K (2018) Sociocultural appearance standards and risk factors or eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Front Psychol 9:429. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00429

Rankin S, Beemyn G (2012) Beyond a binary: the lives of gender-nonconforming youth. Campus 17:2–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21086

McGuire JK, Doty JL, Catalpa JM, Ola C (2016) Body image in transgender young people: findings from a qualitative, community based study. Body Image 18:96–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.06.004

Fassinger RE, Arseneau JR (2007) ‘I’d rather get wet than be under that umbrella’ Differentiating the experiences and identities of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people. In: Bieschke KJ, Perez RM, Debord KA (eds) Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender clients, 2nd edn. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 19–49

Bandini E, Fisher AD, Castellini G et al (2013) Gender identity disorder and eating disorders: similarities and differences in terms of body uneasiness. J Sex Med 10:1012–1023. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12062

Forbush KT, Siew CS, Vitevitch MS (2016) Application of network analysis to identify interactive systems of eating disorder psychopathology. Psychol Med 46:2667–2677. https://doi.org/10.1017/S00329181600012X

Shafran F, Fairburn CG, Robinson P, Lask B (2004) Body checking and its avoidance in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 35:93–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10228

Muth JL, Cash TF (1997) Body-image attitudes: what difference does gender make? J Appl Soc Psychol 27:1438–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1997.tb01607.x

Smolak L, Murnen SK (2008) Drive for leanness: assessment and relationship to gender, gender role and objectification. Body Image 5:251–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.03.004

Alfano L, Hildebrandt T, Bannon K, Walker C, Walton KE (2011) The impact of gender on the assessment of body checking behavior. Body Image 8:20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.09.005

Mountford V, Haase A, Waller G (2006) Body checking in the eating disorders: associations between cognitions and behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 39:708–715. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20279

Brewster ME, Velez BL, Breslow AS, Geiger EF (2019) Unpacking body image concerns and disordered eating for transgender women: the roles of sexual objectification and minority stress. J Couns Psychol 66:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000333

Grant JM, Mottet LA, Tanis J, Herman JL, Harrison J, Keisling M (2010) National transgender discrimination survey report on health and health care. Natl Cent Transgender Equal Natl Gay Lesbian Task Force. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf. Accessed 18 June 2020

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129:674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

McClain Z, Peebles R (2016) Body image and eating disorders among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Pediatr Clin North Am 63:1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.008

Simone M, Askew A, Lust K, Eisenberg ME, Pisetsky EM (2020) Disparities in self-reported eating disorders and academic impairment in sexual and gender minority college students relative to their heterosexual and cisgender peers. Int J Eat Disord 53:513–524. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23226

Murray SB, Boon E, Touyz SE (2013) Diverging eating psychopathology in transgendered eating disorder patients: a report of two cases. Eat Dis 21:70–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2013.741989

Ålgars M, Alanko K, Santtila P, Sandnabba NK (2012) Disordered eating and gender identity disorder: a qualitative study. Eat Disord J Treat Prev 20:300–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.668482

Becker I, Nieder TO, Cerwenka S et al (2016) Body image in young gender dysphoric adults: a European multi-center study. Arch Sex Behav 45:559–574. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0527-z

Hepp U, Milos G (2002) Gender identity disorder and eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 32:473–478. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10090

Witcomb GL, Bouman WP, Brewin N, Richards C, Fernandez-Aranda F, Arcelus J (2015) Body image dissatisfaction and eating-related psychopathology in trans individuals: a matched control study. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc 23:287–293. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2362

Bell K, Rieger E, Hirsch JK (2019) Eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and non-conforming adults: comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Front Psychol 9:2692. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02692

Vocks S, Stahn C, Loenser K, Legenbauer T (2009) Eating and body image disturbances in male-to-female and female-to-male transsexuals. Arch Sex Behav 38:364–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9424-z

Couturier J, Pindiprolu B, Findlay S, Johnson N (2015) Anorexia nervosa and gender dysphoria in two adolescents. Int J Eat Disord 48:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22368

Duffey ME, Henkel KE, Earnshaw VA (2016) Transgender clients’ experiences of eating disorder treatment. J LGBT Issues Couns 10:136–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2016.1177806

Ewan LA, Middleman AB, Feldmann J (2014) Treatment of anorexia nervosa in the context of transsexuality: a case report. Int J Eat Disord 47:112–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22209

Velez BL, Breslow AS, Brewster ME, Cox R, Foster AB (2016) Building a pantheoretical model of dehumanization with transgender men: integrating objectification and minority stress theories. J Couns Psychol 63:497–508. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000136

Becker I, Auer M, Barkmann C et al (2018) A cross-sectional multicenter study of multidimensional body image in adolescents and adults with gender dysphoria before and after transition-related medical interventions. Arch Sex Behav 47:2335–2347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1278-4

Jones BA, Bouman WP, Haycraft E, Arcelus J (2019a) Gender congruence and body satisfaction in nonbinary transgender people: a case control study. Int J Transgenderism 20:263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1538840

Morris ER, Galupo MP (2019) ‘Attempting to dull the dysphoria’: nonsuicidal self-injury among transgender individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 6:296–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000327

Becker I, Nieder TO, Cerweka S et al (2016) Hamburg body drawing scale-revised. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t52318-000

Orbach I, Mikulincer M (1998) The body investment scale: construction and validation of a body experience scale. Psychol Assess 10:415–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0154-5

Dargie E, Blair KL, Pukall CF, Coyle SM (2014) Somewhere under the rainbow: exploring the identities and experiences of trans persons. Can J Hum Sex 23:60–74. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2378

Levitt H (2019) A psychosocial genealogy of LGBTQ+ gender: an empirically based theory of gender and gender identity cultures. Psychol Women Q 43:275–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319834641

Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Heron KE (2018) Disordered eating and body image concerns among sexual minority women: a systematic review and testable model. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 5:397–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000293

Hayfield N, Clarke V, Halliwell E, Malson H (2013) Visible lesbians and invisible bisexuals: appearance and visual identities among bisexual women. Womens Stud Int Forum 40:172–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2013.07.015

Huxley C, Clarke V, Halliwell E (2014) Resisting and conforming to the ‘lesbian look’: the importance of appearance norms for lesbian and bisexual women”. J Community Appl Soc Psychol 24:205–219. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2161

Smith ML, Telford E, Tree JJ (2019) Body image and sexual orientation: the experiences of lesbian and bisexual women. J Health Psychol 24:1178–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317694486

Galupo MP, Pulice-Farrow L, Pehl E (2020) There is nothing to do about it: nonbinary individuals experience of gender dysphoria. Transgend Health. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2020.0041

Reas DL, Whisenhunt BL, Netemeyer R, Williamson DA (2002) Development of the body checking questionnaire: a self-report measure of body checking behaviors. Int J Eat Disord 31:324–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10012

Tylka TL, Wood-Barcalow NL (2015) The body appreciation scale-2: item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image 12:53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006

Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ (1994) Eating disorder examination questionnaire. PsycTESTS. https://doi.org/10.1037/t03974-000

Cooper Z, Fairburn CG (1987) The eating disorder examination: a semi-structured interview for the assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 6:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198701)6:1%3c1::AID-EAT2260060102%3e3.0.CO;2-9

Luce KH, Crowther JH (1999) The reliability of the eating disorder examination-self-report questionnaire version (EDE-Q). Int J Eat Disord 25:349–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3%3c349::aid-eat15%3e3.0.co;2-m

Jones BA, Bouman WP, Haycraft E, Arcelus J (2019b) The gender congruence and life satisfaction scale (GCLS): development and validation of a scale to measure outcomes from transgender health services. Int J Transgenderism 20:63–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1453425

Mayring P (2014) Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173

Walker DC, White EK, Srinivasan VJ (2018) A meta-analysis of the relationships between body checking, body image avoidance, body image dissatisfaction, mood, and disordered eating. Int J Eat Disor 51:745–770. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22867

Nagata JM, Murray SB, Compte EJ et al (2020) Community norms for the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) among transgender men and women. Eat Behav 37:101381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101381

Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C, Beumont PJV (2004) Validity of the eating disorder examination questionnaire (EDE-Q) in screening for eating disorders in community samples. Behav Res Ther 42:551–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00161-X

Lindley L, Galupo MP (2020) Gender dysphoria and minority stress: support for inclusion of gender dysphoria as a proximal stressor. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 7:265–275. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000439

Anderson CB, Bulik CM (2004) Gender differences in compensatory behaviors, weight and shape salience, and drive for thinness. Eat Behav 5:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2003.07.001

Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Moerk KC, Striegel-Moore RH (2002) Gender differences in eating disorder symptoms in young adults. Int J Eat Disord 32:426–440. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10103

Brewster ME, Sandil R, DeBlaere C, Breslow A, Eklund A (2017) ‘Do you even lift, bro?’ objectification, minority stress, and body image concerns for sexual minority men. Psychol Men Masculinity 18:87–98. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000043

Murray SB, Nagata JM, Griffiths S et al (2017) The enigma of male eating disorders: a critical review and synthesis. Clin Psychol Rev 57:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.001

Galupo MP, Pulice-Farrow L, Ramirez JL (2017) ‘Like a constantly flowing river’: gender identity flexibility among nonbinary transgender individuals. In: Sinnott JD (ed) Identity flexibility during adulthood: perspectives in adult development. Springer, London, pp 163–177

Christian LM, Dillmann DA, Smyth JD (2007) The effects of mode and format on answers to scalar questions in telephone and web surveys. In: Lepkowski JM, Tucker C, Brick JM, de Leeuw ED, Japec L, Lavrakas PJ, Link MW, Sangster RL (eds) Advances in telephone survey methodology. Wiley, New York, pp 250–275

McCreary DR, Sasse DK (2000) An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. J Am Coll Health J ACH 48:297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/074484800009596271

Darcy AM, Lin IH (2012) Are we asking the right questions? a review of assessment of males with eating disorders. Eat Disord 20:416–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2012.715521

Shulman GP, Holt NR, Hope DA, Mocarski R, Eyer J, Woodruff N (2017) A review of contemporary assessment tools for use with transgender and gender nonconforming adults. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 4:304–313. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000233

Pulice-Farrow L, Cusack CE, Galupo MP (2020) ‘Certain parts of my body don’t belong to me’: trans individuals’ descriptions of body-specific gender dysphoria. Sex Res Soc Policy 17:654–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00423-y

Kraus N, Lindenberg J, Zeeck A, Kosfelder J, Vocks S (2015) Immediate effects of body checking behaviour on negative and positive emotions in women with eating disorders: an ecological momentary assessment approach. Eur Eat Disord Rev 23:399–407. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2380

Bailey N, Waller G (2017) Body checking in non-clinical women: experimental evidence of a specific impact on fear of uncontrollable weight gain. Int J Eat Disord 50:693–697. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22676

Funding

The authors received no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Towson University (Ethics approval number: 1908054269).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The article is part of the Topical Collection on males and eating and weight disorders.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cusack, C.E., Galupo, M.P. Body checking behaviors and eating disorder pathology among nonbinary individuals with androgynous appearance ideals. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1915–1925 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01040-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-01040-0