Abstract

Background

Fruit and vegetable consumption may beneficially affect the odds of primary headaches due to their antioxidant contents. However, no study has examined the association between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches among university students.

Aim

To assess the relation between fruit and vegetable intakes and primary headaches among Iranian university students.

Methods

Overall, 83,214 university students with an age range of ≥ 18 years participated in the present study. Dietary intakes and also data on confounding variables were collected using validated questionnaires. Data on dietary intakes were collected using a validated dietary habits questionnaire. We used the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) criteria to define primary headaches.

Results

Fruit consumption was negatively associated with primary headaches; such that after controlling for potential confounders, greater intake of fruits was associated with 30% lower odds of primary headaches (OR: 0.70, 95% CI 0.58–0.84). Such an inverse association was also found for vegetable consumption. In the fully adjusted model, students in the top category of vegetable consumption were 16% less likely to have primary headaches compared with those in the bottom category (OR: 0.84, 95% CI 0.74–0.95). Subgroup analysis revealed that fruit consumption was inversely associated with primary headaches in females, unlike males, and vegetable consumption was inversely associated with these headaches in males, as opposed to females. Moreover, fruit and vegetable consumption was related to lower odds of primary headaches in normal-weight students.

Conclusion

Fruit and vegetable intakes were associated with reduced odds of primary headaches.

Level of evidence

Level III, cross-sectional analytic studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fruit and vegetables are key components of healthy dietary patterns [1, 2]. These food groups contain a high amount of fiber, antioxidants, and phytochemicals that are responsible for the anti-inflammatory properties of fruit and vegetables [3, 4]. Adequate consumption of fruit and vegetables can play a protective role against the incidence of inflammation-based diseases including obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular diseases [5,6,7]. However, little attention has been paid to the relation between fruit and vegetable consumption and inflammation-based neurovascular diseases such as primary headaches. In addition to anti-inflammatory properties, fruit and vegetables are rich sources of magnesium and some B-vitamins which are essential for neuronal function [8]. In a cross-sectional study, high intakes of fruit and vegetables were associated with reduced odds of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress [9]. Such findings were also reported for other food groups with nutrients similar to fruit and vegetables [10, 11]. Despite the possible beneficial effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on the nervous system, no study has examined the link between the consumption of these food groups and the odds of primary headaches.

Primary headaches include migraine, tension-type headaches, and non-classifiable headaches [12, 13]. The high prevalence of primary headaches is a major concern for health care systems. In total, 10% to 18% of the general population around the world are affected [14]. This prevalence is even higher among youth such as university students, such that 11.3% of male students and 21.7% of female students suffer from primary headaches [14]. Besides, university students usually have different dietary behaviors or dietary patterns compared with general adults. They might adhere to a poor diet because their diet is affected by food prices, busy daily life, and preferences [15]. It has been shown that university students tend to have energy-dense foods such as fast foods and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in their diet rather than fruit and vegetables [16, 17]. Overall, having a poor diet might be a reason for the high prevalence of primary headaches among university students. However, data in this regard are lacking. Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches among a large population of university students.

Materials and methods

Participants

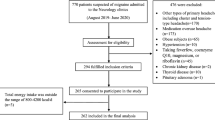

This cross-sectional study was done in the framework of the mental and physical health assessment of university student (MEPHASOUS) project which was carried out in 2012–2013. The purpose of this project was to detect the contributing factors to the health problems and unhealthy behaviors of Iranian university students. Details on the study design, sampling methods, and data gathering in the MEPHASOUS project have been published previously [18, 19]. In the MEPHASOUS study, all students from 74 governmental universities (in 28 provinces of Iran), related to the Ministry of Science and Technology (MST), were asked to participate in the study. Students were included if they were registered at a governmental university and had an age range of ≥ 18 years. To conduct data collection, students were invited to the health centers of universities. All required data on demographic variables, physical activity, anthropometric measures, medical history, and dietary intakes were collected from each student using pre-tested questionnaires. After merging the collected data and removing the students with missing information, 83,214 students with complete data were included in the final analysis. All participants signed the informed consent form. The ethics committee of the MST, Tehran, Iran, approved the whole project (code: 4/5/109779).

Dietary habits

In order to collect dietary data, a self-administered validated dietary habits questionnaire was applied. A previously published article revealed the reliability and validity of the questionnaire [18]. Students were asked to report their dietary intakes for fruit, vegetables, dairy products, fast foods, SSBs, and sweets during the last year. In this questionnaire, the response categories for each food item were different according to its usual intake among the Iranian population. For example, the response categories for fruits that are frequently consumed by Iranians were in a daily format, while these categories for sweets which are infrequently consumed were in a weekly format. In addition to dietary intakes, students were asked to report the frequency of breakfast consumption in a week via these options: < 1 day/week, 1-2 days/week, 3–4 days/wk, ≥ 5 days/week. Breakfast skipper was defined as individuals who consumed breakfast ≤ 4 days/week.

To evaluate fruit consumption, students were asked to consider fresh and dried fruit and then, report their intakes based on these options: < 1 serv/day, 1 serv/day, 2–3 serv/day, ≥ 4 serv/day. In addition, students were asked to report vegetable consumption by use of four-choice response categories: < 1 serv/day, 1 serv/week, 2–3 serv/week, ≥ 4 serv/week. Vegetables were considered as mixed vegetables, potato, tomato, other starchy vegetables, legume, yellow vegetables, and green vegetables. Students’ responses to these two food items were considered as the main exposure variables in the current study.

The reliability and validity of the dietary habits questionnaire were examined in a separate study which was done on a subgroup of 70 students in each center of the MEPHASOUS study (total: 1960 students) [18]. Based on the validation study, this questionnaire presented reliable and valid data on the dietary habits of university students. Also, previous studies that applied this questionnaire for the assessment of dietary habits confirmed the reliability and validity of the questionnaire [19,20,21].

Assessment of primary headaches

Students were asked whether they had experienced primary headaches (including migraine, tension-type headache, and non-classifiable headache) during the last 12 months (yes/no). If yes, they were additionally examined by a general practitioner, who was experienced in terms of neurovascular diseases. If the headache was related to cold, fever or any other types of illnesses, it was rejected for further evaluation. Primary headaches were defined according to the criteria introduced by the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 (ICHD-3) with the exceptions that the number of attacks and the duration of headaches were not included [22].

Assessment of other variables

A self-reported pre-tested questionnaire was used to collect data on age, gender (male/female), education [advanced diploma/bachelor of science (BSc)/master of science (MSc)/medical science (MD)/philosophy of doctor (Ph.D.)], marital status (single/married), occupation (having/not-having), health insurance (having/not-having), smoking (non-smoker/ex-smoker or current smoker), and current use of nutritional supplements (including Fe, Ca, vitamins and other nutritional supplements) (yes/no). Students who were in the advanced diploma, BSc and MD courses were defined as the under-graduate students and those in the MSc and Ph.D. courses were considered as the graduate students. Since health insurance in Iran can cost a lot for people, it was considered as an index for the evaluation of economic status. Therefore, we considered students who had health insurance as economically “good” and those who did not have any type of health insurance as economically “weak”. In addition, sleep pattern was assessed by the two questions: “how is your pattern of sleeping and awaking?” and “how many hours do you sleep in a day?” The response options for the first question were “regular”, “irregular” and for the second question were: “< 6 h/day”, “6–8 h/day”, “8–10 h/day”, “> 10 h/day. Due to the possible influence of internet addiction on dietary behaviors and maybe primary headaches, we assessed the time that each student spent for using of internet-connected devices including computer, cell phone, and notebook: “rarely”, “< 2 h/day”, “2–4 h/day”, and “> 4 h/day”. The use of these devices > 4 h/day was considered as frequent use. Physical activity was assessed via a question in which students were asked how many times per week they do exercise for 30 min. The response options for this question were: “rarely”, “1–2 times/week”, “3–4 times/week”, “> 5 times/week”. We considered students who had physical activity ≥ 3 times/week as physically active and those with a rare physical activity as inactive. Also, having physical activity 1–2 times/week was considered moderate physical activity. In order to measure anthropometric measures, we applied a standard procedure to measure weight and height. We calculated the body mass index (BMI) as weight (kg)/height (in square meters). Overweight and obesity were considered as the BMI of 25–30 and ≥ 30 kg/m2, respectively [11, 23]. Blood pressure was measured two times with a 20-min interval in a seated position after a 5-min rest. The average of two measurements was considered as the final systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg [24].

Statistical analysis

At first, students were categorized based on four categories of fruit (< 1 serv/day, 1 serv/day, 2–3 serv/day, ≥ 4 serv/day) and vegetable (< 1 serv/day, 1 serv/week, 2–3 serv/week, ≥ 4 serv/week) consumption. Then, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess significant differences in continuous variables among the categories of fruit and vegetable consumption. Also, the Chi-square test was used to examine the distribution of categorical variables across the increasing categories of fruit and vegetable consumption. Binary logistic regression in crude and multivariable-adjusted models was used to obtain odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches. This analysis was performed in total and separately by gender and BMI status (< 25/≥ 25 kg/m2). To construct the adjusted models, we first included age and gender (not included in the gender-stratified analysis). Then, we included other variables including marital status, education, occupation, economic status, smoking, the use of internet-connected devices, sleep patterns, hypertension, nutritional supplement use, and breakfast skipping in the second model in addition to age and gender. Further adjustment was made for dietary intakes of fruit (included in the vegetable analysis), vegetables (included in the fruit analysis), dairy products, fast foods, SSBs, and sweets in model 3. In the last model, we additionally controlled for BMI to obtain an obesity-independent association. In this analysis, students in the lowest category of fruit and vegetable consumption were considered as the reference group. To calculate the P-trend for odds ratios across increasing categories of fruit and vegetable consumption, we considered these categories as an ordinal variable in the binary logistic regression. All statistical analyses were done using SPSS software (version 19.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago IL). P values were considered significant at < 0.05.

Results

The mean age of students participated in the current study was 21.5 ± 4.01 years. Primary headaches were prevalent among 9% of students.

Demographic characteristics and dietary habits of participants across categories of fruit and vegetable consumption are shown in Table 1. Students in the highest category of fruit consumption were more likely to be female, married, physically active, have a job, regular sleep pattern, overweight or obesity, hypertension, have a good economic status, and less likely to be university graduate, breakfast skipper, current smoker, use nutritional supplements, frequently use net-connected devices, and have primary headaches compared with those in the lowest category. Also, higher intake of fruit was associated with higher intakes of vegetables, dairy products, sweets, and lower intakes of fast foods and SSBs. In terms of vegetable consumption, compared with students in the lowest category of vegetable consumption, those in the highest category were more likely to be female, married, university graduate, physically active, current smoker, have overweight or obesity, hypertension, have an occupation, a good economic status, and less likely to be breakfast skipper, have regular sleep pattern, use nutritional supplements, frequently use net-connected devices, and have primary headaches. Besides, students in the top category of vegetable consumption had higher intakes of fruit, dairy products, and lower intakes of fast foods, SSBs, and sweets.

Multivariable-adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for primary headaches across categories of fruit and vegetable consumption are presented in Table 2: a significant inverse association was seen between fruit consumption and primary headaches (OR: 0.61, 95% CI 0.54–0.70). This association was also seen after controlling for demographic characteristics, physical activity, and BMI, such that students in the highest category of fruit consumption had 30% lower odds for having primary headaches compared with those in the lowest category (OR: 0.70, 95% CI 0.58–0.84). Regarding vegetable consumption, a significant inverse association was found with primary headaches (OR: 0.69, 95% CI 0.54–0.75). After taking potential confounding variables into account, students in the top category of vegetable consumption were 16% less likely to have primary headaches compared with those in the bottom category (OR: 0.84, 95% CI 0.74–0.95).

Findings from gender and BMI status-stratified analyses for the association between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches are illustrated in Table 3. In both genders, a significant inverse association was found between fruit consumption and primary headaches; however, in the fully adjusted model, this association remained significant in female students and became non-significant in male ones, such that females in the highest category of fruit consumption had 35% lower odds of primary headaches compared with those in the lowest category (OR: 0.65, 95% CI 0.50–0.84). Moreover, vegetable consumption was inversely associated with primary headaches in either gender, but after taking potential confounders into account, this association was only significant in male students. In this association, compared with males in the lowest category of vegetable consumption, those in the highest category were 28% less likely to have primary headaches (OR: 0.72, 95% CI 0.57–0.91). With regard to stratified analysis based on BMI status, fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with reduced odds of primary headaches in normal-weight students. This association was seen either before or after controlling for potential confounders (fruit; OR: 0.71, 95% CI 0.57–0.87, vegetable; OR: 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.96). Among students with overweight or obesity, no significant association was seen between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches in the fully adjusted model.

Discussion

In the present study, fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with reduced odds of primary headaches. This association was different between male and female students. In females, unlike males, fruit consumption was inversely associated with primary headaches, while vegetable consumption was inversely associated with these headaches in males in contrast to females. In addition, fruit and vegetable consumption was related to decreased odds of primary headaches in normal-weight students. To our knowledge, this study was the first investigation that examined the association of fruit and vegetable consumption with primary headaches.

It is well-known that diet has an important role in the prevention and also the onset of primary headaches [25]. For instance, it has been shown that chocolate, processed meats, and red wine are dietary triggers for primary headaches [26]. Conversely, our group recently showed that dairy consumption has a protective association with these headaches [13]. However, to date, there is no evidence to elucidate the role of fruit and vegetable consumption in the etiology of primary headaches. In the current study, higher intakes of fruit and vegetables were related to decreased odds of primary headaches. In line with our findings, a descriptive study revealed that the fruit and vegetable intakes in women with migraine were lower than healthy individuals [27]. Also, in a cross-sectional study, adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet, that is rich in fruit and vegetables, was associated with reduced severity and duration of headaches in patients with migraine [28]. The beneficial effects of a diet high in fruit and vegetables were also reported in the study of Ferrara et al. in which, adherence to a low-fat diet, containing a high amount of fruit and vegetables, significantly reduced the severity and frequency of migraine attacks [29]. In a randomized clinical trial, a traditional syrup from Citrus medica L. fruit juice had a therapeutic effect on migraine patients so that reduced headache intensity and the duration of migraine attacks [30]. Overall, based on our findings and current evidence, patients with primary headaches may benefit from high consumption of fruit and vegetables, particularly in the context of a healthy diet. However, further studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Fruit and vegetables are rich sources of antioxidants and phytochemicals which provide anti-inflammatory effects [31]. Since the inflammation is a contributing factor to primary headaches, fruit and vegetable intakes can reduce the odds of primary headaches through their anti-inflammatory effects [32]. Fruit and vegetables contain a high amount of fiber and prebiotics through which they can have a beneficial effect on gut microbiota and gut–brain axis [33]. It has been proposed that gut microbiota imbalance is a trigger factor for primary headaches [34]. Furthermore, fruit and vegetables are key components of weight loss programs [35]. Since obesity is a known risk factor for primary headaches, fruit and vegetable consumption might have a protective role against primary headaches via obesity-preventive effects [36].

Surprisingly, the associations between fruit and vegetable consumption and primary headaches were different between male and female students. This disparity might be explained by the different influences of sex hormones on the neurological system and consequently primary headaches [37, 38]. Furthermore, the accuracy of data on dietary intakes might be different between males and females [11, 39]. It has been proposed that actual dietary behaviors, self-reported preferences for foods and the accuracy of reported dietary intakes are different between males and females [2, 40]. Moreover, we found no significant association between fruit and vegetable intakes and primary headaches in students with overweight or obesity as opposed to normal-weight students. Obesity is associated with sub-clinical inflammation [41, 42]. Given the inflammation plays an important role in the etiology of primary headaches [43], it may diminish the beneficial effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on headaches in obese individuals.

This study had several strengths. We recruited a large sample of students and therefore, the accuracy of estimates in the present study would be high. Several covariates were included in adjusted models to exclude their confounding effects and obtain an independent association. Stratified analysis was done to see if the associations were different among male and female students and those with different BMI status. Participants in this study were high-educated and therefore, the accuracy of the collected data is estimated to be high. Despite these strengths, some limitations should be considered. This study had a cross-sectional design. Hence, we could not establish a causal link between fruit and vegetable intake and primary headaches. We assessed overall primary headaches, while specific types of primary headaches might respond to fruits and vegetables differently. In the current study, only health insurance (having/not-having) was considered as an index of economic status. However, considering data on house possession or having a car let us evaluate economic status more accurately. Since no data were available on psychological disorders and residual lifestyle factors, we could not exclude the confounding effects of these variables from the obtained associations. In addition, since the participants of the current study were university students, we could not extrapolate our findings to other populations. Misclassification of study participants in terms of fruit and vegetable consumption is another limitation of this study.

Conclusion

High intakes of fruit and vegetables were associated with decreased odds of primary headaches. Also, fruit consumption was inversely associated with primary headaches in females, in contrast to male students, and vegetable consumption was inversely associated with these headaches in males, but not in females. Moreover, fruit and vegetable consumption was related to lower odds of primary headaches in normal-weight students. Further studies are needed to confirm our findings and examine the association of fruit and vegetable consumption with different types of primary headaches including migraine, tension-type headaches, and non-classifiable headaches.

What is already known on this subject?

Despite the possible beneficial effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on the nervous system, no study has examined the link between the consumption of these food groups and the odds of primary headaches.

What this study adds?

Fruit and vegetable intakes were associated with decreased odds of primary headaches. Also, fruit consumption was inversely associated with primary headaches in females and vegetable consumption was inversely associated with these headaches in males. Moreover, fruit and vegetable consumption was related to lower odds of primary headaches in normal-weight students.

References

Taghavi M, Sadeghi A, Maleki V, Nasiri M, Khodadost M, Pirouzi A et al (2019) Adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension-style diet is inversely associated with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Nutr Res 72:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2019.10.007

Sadeghi O, Keshteli AH, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P (2019) Adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern is inversely associated with depression, anxiety and psychological distress. Nutr Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415x.2019.1620425

Veronese N, Solmi M, Caruso MG, Giannelli G, Osella AR, Evangelou E et al (2018) Dietary fiber and health outcomes: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Am J Clin Nutr 107:436–444. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqx082

Rocha VZ, Ras RT, Gagliardi AC, Mangili LC, Trautwein EA, Santos RD (2016) Effects of phytosterols on markers of inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 248:76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.01.035

Vergnaud AC, Norat T, Romaguera D, Mouw T, May AM, Romieu I et al (2012) Fruit and vegetable consumption and prospective weight change in participants of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition-Physical Activity, Nutrition, Alcohol, Cessation of Smoking, Eating Out of Home, and Obesity study. Am J Clin Nutr 95:184–193. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.111.019968

Julius JK, Fernandez CK, Grafa AC, Rosa PM, Hartos JL (2019) Daily fruit and vegetable consumption and diabetes status in middle-aged females in the general US population. SAGE Open Med 7:2050312119865116. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119865116

Lamb MJ, Griffin SJ, Sharp SJ, Cooper AJ (2017) Fruit and vegetable intake and cardiovascular risk factors in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Eur J Clin Nutr 71:115–121. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2016.180

Mikkelsen K, Stojanovska L, Apostolopoulos V (2016) The effects of vitamin B in depression. Curr Med Chem 23:4317–4337. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867323666160920110810

Saghafian F, Malmir H, Saneei P, Keshteli AH, Hosseinzadeh-Attar MJ, Afshar H et al (2018) Consumption of fruit and vegetables in relation with psychological disorders in Iranian adults. Eur J Nutr 57:2295–2306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1652-y

Anjom-Shoae J, Sadeghi O, Keshteli AH, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P (2020) Legume and nut consumption in relation to depression, anxiety and psychological distress in Iranian adults. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-020-02197-1

Sadeghi O, Hassanzadeh-Keshteli A, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P (2019) The association of whole and refined grains consumption with psychological disorders among Iranian adults. Eur J Nutr 58:211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1585-x

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, Jensen R, Katsarava Z (2018) Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50 s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain 19:17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0846-2

Mansouri M, Sharifi F, Varmaghani M, Yaghubi H, Shokri A, Moghadas-Tabrizi Y et al (2020) Dairy consumption in relation to primary headaches among a large population of university students: the MEPHASOUS study. Complement Ther Med 48:102269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102269

Wang X, Zhou HB, Sun JM, Xing YH, Zhu YL, Zhao YS (2016) The prevalence of migraine in university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 23:464–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12784

Vilaro MJ, Colby SE, Riggsbee K, Zhou W, Byrd-Bredbenner C, Olfert MD et al (2018) Food choice priorities change over time and predict dietary intake at the end of the first year of college among students in the U.S. Nutrients. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091296

Hilger J, Loerbroks A, Diehl K (2017) Eating behaviour of university students in Germany: dietary intake, barriers to healthy eating and changes in eating behaviour since the time of matriculation. Appetite 109:100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.016

Betancourt-Nunez A, Marquez-Sandoval F, Gonzalez-Zapata LI, Babio N, Vizmanos B (2018) Unhealthy dietary patterns among healthcare professionals and students in Mexico. BMC Public Health 18:1246. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6153-7

Mansouri M, Sharifi F, Varmaghani M, Yaghubi H, Tabrizi YM, Raznahan M et al (2017) Iranian university students lifestyle and health status survey: study profile. J Diabetes Metab Disord 16:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40200-017-0329-z

Mansouri M, Hasani-Ranjbar S, Yaghubi H, Rahmani J, Tabrizi YM, Keshtkar A et al (2018) Breakfast consumption pattern and its association with overweight and obesity among university students: a population-based study. Eat Weight Disord. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0609-8

Mansouri M, Miri A, Varmaghani M, Abbasi R, Taha P, Ramezani S et al (2019) Vitamin D deficiency in relation to general and abdominal obesity among high educated adults. Eat Weight Disord 24:83–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-018-0511-4

Mansouri M, Abasi R, Nasiri M, Sharifi F, Vesaly S, Sadeghi O et al (2018) Association of vitamin D status with metabolic syndrome and its components: a cross-sectional study in a population of high educated Iranian adults. Diabetes Metab Syndr 12:393–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.01.007

McAbee GN, Morse AM, Assadi M (2016) Pediatric aspects of headache classification in the international classification of headache disorders-3 (ICHD-3 beta version). Curr Pain Headache Rep 20:7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-015-0537-5

Dabbagh-Moghadam A, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Nasiri M, Miri A, Rahdar M, Sadeghi O (2017) Association of white and red meat consumption with general and abdominal obesity: a cross-sectional study among a population of Iranian military families in 2016. Eat Weight Disord 22:717–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0385-x

Vaduganathan M, Pareek M, Qamar A, Pandey A, Olsen MH, Bhatt DL (2018) Baseline blood pressure, the 2017 ACC/AHA high blood pressure guidelines, and long-term cardiovascular risk in SPRINT. Am J Med 131:956–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.12.049

Barbanti P, Fofi L, Aurilia C, Egeo G, Caprio M (2017) Ketogenic diet in migraine: rationale, findings and perspectives. Neurol Sci 38:111–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-017-2889-6

Finocchi C, Sivori G (2012) Food as trigger and aggravating factor of migraine. Neurol Sci 33(Suppl 1):S77–S80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-012-1046-5

Nazari F, Eghbali M (2012) Migraine and its relationship with dietary habits in women. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 17:S65–S71

Mirzababaei A, Khorsha F, Togha M, Yekaninejad MS, Okhovat AA, Mirzaei K (2018) Associations between adherence to dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and migraine headache severity and duration among women. Nutr Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415x.2018.1503848

Ferrara LA, Pacioni D, Di Fronzo V, Russo BF, Speranza E, Carlino V et al (2015) Low-lipid diet reduces frequency and severity of acute migraine attacks. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 25:370–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2014.12.006

Jafarpour M, Yousefi G, Hamedi A, Shariat A, Salehi A, Heydari M (2016) Effect of a traditional syrup from Citrus medica L. fruit juice on migraine headache: a randomized double blind placebo controlled clinical trial. J Ethnopharmacol 179:170–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2015.12.040

Almeida-de-Souza J, Santos R, Lopes L, Abreu S, Moreira C, Padrao P et al (2018) Associations between fruit and vegetable variety and low-grade inflammation in Portuguese adolescents from LabMed Physical Activity Study. Eur J Nutr 57:2055–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1479-y

Ramachandran R (2018) Neurogenic inflammation and its role in migraine. Semin Immunopathol 40:301–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00281-018-0676-y

Henning SM, Yang J, Shao P, Lee RP, Huang J, Ly A et al (2017) Health benefit of vegetable/fruit juice-based diet: role of microbiome. Sci Rep 7:2167. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-02200-6

Arzani M, Jahromi SR, Ghorbani Z, Vahabizad F, Martelletti P, Ghaemi A et al (2020) Gut-brain Axis and migraine headache: a comprehensive review. J Headache Pain 21:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-020-1078-9

Williams RL, Wood LG, Collins CE, Callister R (2016) Comparison of fruit and vegetable intakes during weight loss in males and females. Eur J Clin Nutr 70:28–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.123

Miri A, Nasiri M, Zonoori S, Yarahmad F, Dabbagh-Moghadam A, Askari G et al (2018) The association between obesity and migraine in a population of Iranian adults: a case-control study. Diabetes Metab Syndr 12:733–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.04.020

Merki-Feld GS, Imthurn B, Gantenbein AR, Sandor P (2019) Effect of desogestrel 75 microg on headache frequency and intensity in women with migraine: a prospective controlled trial. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 24:175–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2019.1605504

Roque C, Mendes-Oliveira J, Duarte-Chendo C, Baltazar G (2019) The role of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 on neurological disorders. Front Neuroendocrinol 55:100786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.100786

Anjom-Shoae J, Sadeghi O, Hassanzadeh Keshteli A, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A, Adibi P (2018) The association between dietary intake of magnesium and psychiatric disorders among Iranian adults: a cross-sectional study. Br J Nutr 120:693–702. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114518001782

Anjom-Shoae J, Keshteli AH, Sadeghi O, Pouraram H, Afshar H, Esmaillzadeh A et al (2019) Association between dietary insulin index and load with obesity in adults. Eur J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02012-6

Sadeghi O, Sadeghian M, Rahmani S, Maleki V, Larijani B, Esmaillzadeh A (2019) Whole-grain consumption does not affect obesity measures: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Adv Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmz076

Cox AJ, West NP, Cripps AW (2015) Obesity, inflammation, and the gut microbiota. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3:207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(14)70134-2

Cavestro C, Ferrero M, Mandrino S, Di Tavi M, Rota E (2019) Novelty in inflammation and immunomodulation in migraine. Curr Pharm Des 25:2919–2936. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612825666190709204107

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the staffs, fieldworkers, and participants of the MEPHASOUS project that without whom this work would not have been possible. This study was supported by the Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran.

Funding

The study was financially supported by the Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran, in collaboration with the health organization of Ministry of Science and Technology (CHOMST), Tehran, Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MM, FS, MV, and AK contributed to study conception, design, and data collection. OS contributed to statistical analysis. OS, HR and AS contributed to manuscript drafting. All authors acknowledge the full responsibility for the analyses and interpretation of the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants provided a signed written consent form. The ethics committee of the MST, Tehran, Iran, approved the whole project (code: 4/5/109779).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mansouri, M., Sharifi, F., Varmaghani, M. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to primary headaches: the MEPHASOUS study. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1617–1626 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00984-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00984-7