Abstract

Purpose

The present study was performed to develop the Persian version of food craving inventory (FCI) (FCI-P) and to assess food craving in Iranian adult population. In addition, individual differences, including sex and body mass index (BMI) in food craving were assessed.

Methods

Eight hundred and twenty subjects who participated in the same study Hill (Proc Nutr Soc 66: 277–285, 2007) were studied (540 women and 280 men). The FCI-P, International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ), and a questionnaire pertaining to demographic characteristics were completed for all participants.

Results

Good content, construct, and convergent validity was observed for the FCI-P. A good reliability was found for both aggregate scores of the FCI-P and scores of its five factors. Exploratory factor analysis showed a five-factor model including “sweets,” “high-fat foods,” “fast food fats,” “carbohydrates/starches” and “high-fat meats”. These five factors accounted for 47.31% of the total variance. The scores of “uncontrolled eating” and “emotional eating” of the TFEQ were significantly correlated with the scores of the FCI-P factors and its total score. A significant correlation was found between BMI and the FCI-P score (r = 0.199). Significant differences were observed in the mean age and physical activity score among normal weight, overweight, and obese participants. Normal weight and overweight groups were more active than obese group. Obese participants had higher FCI-P score (P < 0.001) than the normal and overweight groups. FCI-P score was significantly higher in women than men.

Conclusions

FCI-P can be used as a valid and reliable measure to assess food craving in Iranian populations. Obese individuals experienced food craving more than normal weight subjects. Similarly, women may experience food craving more than men.

Level of evidence

Level V, cross sectional study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is an important health problem in both developing and developed countries. The phenomena of calories in vs. calories out, which was previously thought to be a simple problem has now been turned into a complex and multifactorial condition that is influenced not only by genes but also by current obesogenic environment [1,2,3]. One of the most important factors in obesity is overeating in response to obesogenic environment in which, different highly palatable foods are available [4]. Some forms of overeating have the characteristics similar to addicted behavior. In recent years, the term “food addiction” has been used to refer to addictive-like eating behaviors [5]. There is an increasing evidence supporting the involvement of the “food addiction” in obesity severity and body composition [5,6,7]. “Food addiction” is associated with symptoms such as loss of control over eating, continued consumption in spite of negative consequences, and failure to cut down regardless the desire to do so [8].

Food craving is a core component of food addiction and is defined as “an intense desire to consume a particular food (or type of foods) that is difficult to resist” [9]. People frequently acknowledge food cravings as the reason for failure to adhere to diet [10]. Previous studies revealed that most of the people might experience craving for some kinds of food [11,12,13]. In normal‐weight subjects, food cravings is more often related to eating events, including breakfast, lunch and dinner, and food craving seen mostly for foods that are typically consumed at these eating events [13]. On the other hand, some studies have found that overweight and obese subjects experience food craving more frequently than normal ones [13,14,15]. It has been reported that the obesity prevalence is higher in women than in men [16,17,18]. Although sex differences in food craving may be one of the underlying mechanism explaining the difference in obesity prevalence among men and women [19]. There are relatively few studies which investigated the sex difference in food craving.

Since food craving is a potential risk factor for obesity, developing appropriate tools for measuring craving for different kinds of food is warranted. In this context, the Food Craving Inventory (FCI) has emerged as a psychometrically valid self-reported measure of specific food cravings [20].To date, the FCI has been translated into several languages, including British English [21], German [22], and Japanese [23]. It has been shown that the frequency, strength, and types of food cravings are different between communities and affected by culture [23, 24]. For instance, chocolate is the most craved food in the UK [23], while in Japan, the majority of people have craving for rice and sushi [20], and in Egypt, salty foods are the major targets for craving [25].

There are limited studies investigating the relationship between addictive-like eating, craving, and eating-related concerns. It has been shown that the frequency, strength, and types of food cravings are different between communities [23]. In addition, differences in the levels of physical activity may be a confounding factor in food choices and intake. Given the fact that there are differences across different countries in the frequency, strength, and types of food cravings, possibly because of the differences in ethnic, and cultural and social backgrounds, the present study was performed to develop the Persian version of food craving inventory (FCI-P) and to investigate the psychometric and measurement properties of it. In addition, we sought to assess whether individual differences, including sex and body mass index (BMI) are associated with the food craving measured by the FCI-P.

Materials and methods

Subjects and study design

This study was conducted in Tabriz, North-West of Iran, during December 2016 to August 2017. The subjects were those who participated in the same study reporting the validated Persian version of the Power of Food Scale [26] and the present one is a part of the already published study [26]. However, the present study presents new knowledge, including the development of the Persian version of food craving inventory (FCI-P) and the assessment of whether individual differences, including sex and body mass index (BMI) are associated with the food craving. In addition, any of the data presented in the previous article [26] is not repeat here, except age and BMI of the participants.

The subjects were recruited through announcements and flyer distribution in public areas of the city and health care centers. At the first visit, the aim of the study was described for the participants. The inclusion criteria were age between 19 and 50 years, and living in Tabriz for at least 5 consecutive years. Female participants were also required to be pre-menopausal as identified by the self-reporting of regular menstrual cycles and they were neither pregnant nor lactating at the time of the study. Subjects with any psychotic disorder, substance abuse, alcoholism, or a serious medical illness such as cardiovascular and/or endocrine diseases and those with significant weight loss during the last 6 months were excluded from the study. The initial sample consisted of 1050 adults and after eligibility screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 820 participants (540womenand280men) were included in the study. The FCI-P, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [27], the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) [28] and a questionnaire pertaining to demographic characteristics were completed for the participants.

Anthropometric measurements

Participants’ weight and height were measured while wearing light clothes and shoeless after a 12-h fasting period. Weight was measured with a calibrated electronic scale (SECA Birmingham, UK) with an accuracy of 0.1 kg. A fixed stadiometer was used to measure height to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI was calculated by dividing the participant’s weight in kilograms by the square of his/her height in meter (kg/m2).

Physical activity

Since differences in the levels of physical activity may be a confounding factor in food choices and intake, we studied the physical activity of the participants. The validated short form of the Persian version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire [27, 29] was used to estimate the participant’s physical activity levels. According to the questionnaire, the participants were divided into low, moderate and high active groups [28]. The high active group was those with vigorous intensity activity on at least 3 days or five or more days of any combination of walking, moderate intensity or vigorous intensity activities. The moderate active group was those who engaged in 3 or more days of vigorous intensity activity and/or walking of at least 30 min per day, or 5 or more days of moderate intensity activity and/or walking of at least 30 min per day, or 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate intensity or vigorous intensity activities achieving a minimum total physical activity of at least 600 MET minutes a week. The low active group was the participants who did not meet any of the criteria for either moderate or high levels of physical activity [29].

FCI questionnaire

The FCI questionnaire was first developed, in 2002, by White et al., to measure cravings of different types of foods [30]. In the present study, the Persian version of FCI was developed which includes 28 food items in four groups: group (1) high fat foods (fried chicken, sausage, gravy, fried fish, bacon, corn bread, hot dog, and steak(, group (2) sweets (brownies, cookies, candy, chocolate, donuts, cake, cinnamon rolls, and ice cream), group (3) carbohydrates/starches (rolls, pancake waffles, biscuits, sandwich bread, rice, baked potato, pasta, and cereal), and group 4) fast food lipids (hamburger, French fries, chips, and pizza). Following instructions: ‘‘A craving is defined as an intense desire to eat a particular food that is so strong that you feel difficulty to resist eating’’ were appeared on the top of the questionnaire. The participants were asked to answer the question of "How often have you experienced a craving for the food listed below over the past month?". The subjects were required to respond the questions using a five-point scale, scoring from 0 to 4, where 0 = never; 1 = rarely; 2 = sometimes; 3 = often; and 4 = always/almost every day) based on the craving intensity.

Validation procedure

Translation process

The English version of the FCI was translated into Persian according to the standardized cross-cultural translation guidelines project [31]. The translation was performed by two independent native Persian speakers who were fluent in English and expert in food eating behavior. The translators discussed their translations and provided an agreed translation. Then, the Persian version of the questionnaire was back translated into English by a third translator who was not aware of the original English version. Finally, the forward–backward and original versions of the questionnaire were compared to obtain a final FCI-P.

Original English version of FCI conveys some food items that are not common in Iranian food culture. These items were assessed by a 10-member panel of academic professionals in the field of nutrition and eating behavior. According to the consensus of the professional panel, food items that were not consistent with Iranian food culture were replaced by popular foods in the studied community. Finally, a preliminary questionnaire with 42 food items was obtained.

Content validity

The content validity of the FCI-P was assessed based on the feedback of a 10-member team experienced in the field of nutrition and food behaviors. They were asked to evaluate the questionnaire qualitatively in terms of the Persian grammar, appropriate word usage, and locating food items in their proper place and then score each item. Considering the team feedback, some modifications were applied which includes removal of some food items from the questionnaire or combination in one food group because of their high similarity. For instance, "Donar Kebab", a highly popular food in Tabriz, and other types of "Kebab" such as "Kebab Koobideh", "Kebab Barg", “Kebab Bonanb”, etc. were considered as a single food group of "Kebabs". Salty/crunchy items such as "Chips" and "Poffak" were regarded as a food group of “junk foods ". In addition, some food items that were not common in Iranian food culture were replaced by those which are popular among Iranians. For instance, "gravy" was substituted by "Abgoosht". Ultimately, a 28 food item questionnaire was achieved. For quantitative assessment, Content Validity Ratio and Content Validity Index were calculated.

Face validity

To assess the face validity, the final Persian version of the questionnaire with 28 food items (FCI-P) was administered to 30 subjects to assess the difficulty, irrelevancy and ambiguous of the questions. Based on this survey, some required modifications were applied.

Construct validity

The factor structure of the FCI-P was examined using the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) utilizing principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation [21, 22]. A factor loading value of 0.4 was used to allocate an item to the factor. To have a satisfactory factor analysis, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin values of > 0.7 and significance of Bartlett’s test of sphericity (P < 0.05) were used [22]. To confirm the adequacy of the EFA extracted model to the observed data, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was applied. The CFA was carried out on a separate sample, including 100 men and 200 women. In the CFA, the method of weighted least squares for estimation was used. The fit indices and reasonable values of them for the CFA were a Chi-squared to degree of freedom ratio of < 5, root mean square error of approximation of < 0.08, and comparative fit index, and non-normed fit index of > 0.9 [32, 33].

Convergent validity

According to the original FCI validation, we used the TFEQ as a measure of convergent validity. The TFEQ is one of the most widely used instruments for assessing eating behavior worldwide. Therefore, the Persian version of the TFEQ [27] was used in the present study. The questionnaire consists of three subscales measuring "uncontrolled eating", "emotional eating" and "cognitive restraint". It consists of 18 items which are responded on a four-point scale (definitely true/mostly true/mostly false/definitely false). The scores of the items are then summated into the scale scores. Previous studies showed that “uncontrolled eating" and "emotional eating" scales correlated with food craving, but "cognitive restraint” did not [20, 22, 30, 34].

Reliability

Test–retest reliability and internal consistency were used to assess the reliability of the FCI-P. Forty subjects, including 15 men and 25 women completed the questionnaire twice, with a 2-week interval. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and its confidence interval were obtained for each item. For internal consistency, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for the whole questionnaire and its factors separately.

Statistical analysis

Version 23.0 of SPSS software and version 23.0 of Amos software were used to analyze data. Descriptive results are presented as arithmetic mean ± SD and frequency (%). The normality of the distribution of data was assesses using skewness (absolute values < 3) and kurtosis (absolute values < 10) [35, 36]. Each domain was scored by averaging the scores of the related questions of that domain. The missing data were imputed using multiple imputation method utilizing the MCMC procedure. Pearson correlation was used to assess the relationship between questionnaires scales and BMI. Participants were categorized to three group based on their BMI as normal (≥ 18.5 and < 25), overweight (≥ 25 and < 30), and obese (≥ 30). The comparisons between three groups were conducted using analysis of covariance with the age and sex as covariates. The Sidak post hoc test was used as post hoc test. In addition, sex differences in the scores of FCI-I were examined using the Student’s t test. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

All data were normally distributed and about 66% (540subjects) of the participants were women. The mean age of the men and women were 35.99 ± 8.02 and 35.93 ± 8.91 years, respectively (p = 0.92). There was a statistically significant difference in the BMI between men (28.36 ± 3.95 kg/m2) and women (30.50 ± 6.62 kg/m2) (p < 0.001). The obtained 28 item FCI-P (see the sections of face and content validity) were entered into the factor analysis. The adequacy of the factor model was confirmed by the value of 0.877 for the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin values and p < 0.05 for the Bartlett’s test. Table 1 shows the rotated factor loadings. Principal axis factoring and oblimin rotation revealed a five-factor model including “sweets,” “high-fat foods,” “fast food fats,” “carbohydrates/starches” and “high-fat meats”. These five factors accounted for 47.31% of the total variance. “Tah-dig” and “Nuts” were excluded from the final list of items because of the coefficient point lower than 0.4 and FCI-P was obtained with 26 food item. In addition, the five-factor structure obtained in the EFA was approved by the CFA using a structural equation modeling procedure, which was performed in a separate sample (100 men and 200 women). The results of CFA for both original version of FCI with four factors and the exploratory version with five factors proposed by the EFA are presented in Table 2. The Comparison of the modal fit of these two versions indicated that the exploratory version was well-adjusted. We used multigroup CFA to examine the extent of measurement invariance between men and women. No significant difference was observed, and thus the homogenous structure could be inferred.

Table 3 shows the correlation of the five factors of FCI-P with the three subscales of the TFEQ (convergent validity) and BMI. The scores of “uncontrolled eating” and “emotional eating” of the TFEQ significantly correlated with the scores of the FCI-P factors and its total score. Although, such a correlation was not found for “cognitive restraint”, a weak correlation was found between this scale and fast food fat. Also, BMI significantly correlated with the scores of the FCI-P factors and its total score.

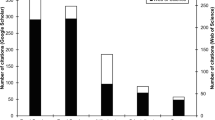

The 10 food items with the highest mean score are illustrated in Fig. 1. As seen, carbohydrates and sweets are at first and second place in the list. "Bread", "rice", and "candies" were the most frequently craved foods with the 2.54, 2.48, and 2.07, scores, respectively.

Table 4 indicates the comparison of food craving between the normal weight, overweight, and obese participants after adjusting for age, sex and physical activity. Significant differences were observed in the mean age and physical activity score among normal weight, overweight, and obese participants. Normal weight and overweight groups were more active than obese group. There were significant differences the total score of FCI-P and its factors between the groups, with the exception for sweets. The least significant difference, as post hoc test, showed significant differences between three groups in food craving total scores.

To examine sex-based food preferences and to compare the scores of men and women in each factor of the FCI-P a series of covariance analysis, adjusted for BMI and physical activity was conducted. As indicated in Table 5, women scored significantly higher on craving for sweets, fast food fat, and carbohydrate/starch. Whereas, the high fat and meat fat subscales were significantly higher in men compared to women. In general, the total score of food craving was remarkably higher in women than men.

The reliability analysis of the FCI-P showed the Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.80 for the total score, 0.80 for “sweets”, 0.72 for “high-fat foods”, 0.79 for “fast food fats”, 0.70 for “carbohydrates/starches”, and 0.70 for “high-fat meats”. Satisfactory internal consistency and ICC (ranged from 0.72 to 0.95) were observed for all factors. These results supported the test–retest reliability of the FCI-P.

Discussion

The present study was performed to develop the Persian version of FCI (FCI-P) and to investigate food craving among an Iranian sample. The studied participants were those who participated in the same study to validate the Persian version of power of food scale [26]. The present study showed that food craving would give rise to obesity and there is sex differences in food craving, which may highlight documented sex differences in obesity prevalence. The FCI-P can be used to identify food craving behavior in Iranian populations. In addition, the present study, provides more evidence that the application of FCI may be useful in understanding the complex etiology of obesity and improving weight loss programs and weight maintenance.

Given the fact that, food patterns of Asian countries varies from that of Western countries, it was not surprising that some food items in the original version of FCI seemed to be unfamiliar to Iranian people. These food items were identified by a panel of experts and replaced by those that are common in the studied community. After the validation procedure, the final version of the FCI-P was obtained with 26 food items which was categorized in five factors, including “sweets,” “carbohydrates/starches,” “high-fat foods,” “high-fat meats” and “fast food fats” that were largely similar to those in the original version of FCI [30]; however, the high fat foods were loaded in two factors, including high-fat foods and high-fat meats. Although, the high-fat meats can also be considered as traditional foods, they were named as “high-fat meats” to match more with the original factors. In a study in Japan, food craving investigation by 21-item FCI-J, also revealed five factors structure that the two factors of “rice” and “sushi” were Japanese traditional foods [20]. A study in Brazil reported a 23 item FCI-Br, distributed in three factors: “high Fat”, “sweet food”, and” traditional meal” without a specific factor for carbohydrates/starches and “traditional meal” dimension was composed of carbohydrates, beans, meat, and cheese [37]. The Spanish version of the FCI was consisted of 28 items and five factors in which high fat foods and fast food fats were loaded in one factor [38]. A brief review of different versions of the FCI questionnaire as well as the one designed in this study indicated that the sweet foods dimension remains stable compared to the other dimensions [20, 21, 30, 37, 38]. Moreover, the results of the CFA confirmed the fit indices of the exploratory model in present study (Table 2). The test–retest and ICC analyses showed acceptable reliability for the FCI-P factors and its total score. The criterion validity of the FCI-P was confirmed by the strong correlations between the factors of FCI-P and its total score with the two subscales of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire, “uncontrolled eating” and “emotional eating” [22]. In line with previous studies [30, 34], no significant correlation was found between the total score of the FCI-P and “cognitive restraint”. Overall, the results indicated that the FCI-P was satisfactory in terms of its content, construct, and criterion validations.

People in diverse cultures tend to eat different foods and, therefore, crave for various foods [39]. For instance, compared to Japanese young females, Spanish people have more craving for white chocolate [20]. In the present study, bread and rice were the most frequent craved foods, a findings that is in line with the Komatsu’s conclusion who showed that rice craving is a characteristic of Asian rice consuming countries [20]. Like many other Asian countries, bread and rice are the most preferred staple in Iran which provide main proportions of calorie intake among Iranians [40, 41]. In addition, with an average annual per capita consumption of about 34 kg, Iran is the 3rd biggest consumer of white rice in the world [42]. Recent studies have suggested that more craving lead to higher intake of the craved foods [43,44,45]. For instance, Martin et al., investigated the association between food cravings and intake of specific foods in a laboratory setting. They found that food craving for a given food, measured by the FCI, was significantly related to the consumption of that food or similar foods. For instance, a person who was craved for sweets consumed more jelly or M&M than other participants (45). Thus, strong associations between food craving, increased food intake and weight gain as a consequence has been demonstrated [46,47,48]. In agreement with other studies [14, 49], in the present study, significant correlations were observed between BMI and the factors of FCI-P as well as its total score; Craving for carbohydrate/starch showed the strongest correlation with BMI. Furthermore, there were significant differences in food craving total score and craved foods between normal weight, overweight, and obese participants, except for sweets. These findings are in accordance with recent studies indicating that self-reported food cravings are usually more among overweight and obese individuals compared to normal weight participants [50,51,52]. It has also been reported that craving plays a major role in food addiction process ending in excessive food consumption which in turn increase weight gain in a subset of obese population [50, 53,54,55,56]. Furthermore, several studies have indicated that obesity is associated with reduced dopaminergic receptor, an important element of the brain reward system, which is correlated with addictive-like eating [57,58,59,60].

Several factors such as the level of nutrition awareness, cultural background, psychological or physiological changes related to menstruation, and differences in dietary and mood-regulating neurotransmitters may lead to sex differences in eating behaviors and food cravings severity [61, 62]. According to some studies, there are sex differences in general food cravings prevalence; being more common in women than men [12, 63, 64]. Similarly, women experienced more food craving than men in the present study which might be explained partially, by the fact that women have greater neural activation in brain regions associated with food cues and reward eating [65, 66]. In this regard, some studies also reported more craving for sweets and carbohydrates in women [12, 63, 67]. Consistent with other studies, women craved also more for sweets, carbohydrate/starch and fast food fat in the present study [19, 68, 69]. Although sweet taste preference is innate in humans, and usually is accompanied by "hedonic reward", the remarkable sweet preferences in women appear to correlate strongly with hormonal changes [61, 70,71,72,73]. As well, the food items included in the high fat meats (e.g., fried fish, Kebabs, fried chicken, and Abgoosht) could be considered as Iranian traditional meals. These kinds of food usually content high fats and interestingly, the both factors scores of high fats and high fat meats were higher in male participants which in line with the previous studies [19, 65, 66]. Higher score of food craving in women than men confirmed the discriminant validity of the FCI-P [21, 38].

Large sample size, especially for women participants which provided adequate statistical power for factor analysis was one of the strengths of the present study. The wide ranges of subjects’ age and BMI could be considered as another strength point of the present study. However, the inequality of male and female participants’ number was one of the limitations. In addition, since this study was carried out in Tabriz, one of the major cities in northwest of Iran, further studies with larger sample sizes in different parts of Iran are recommended to assess Iranian populations’ food craving. Another limitation was the use of a same population to validate two different questionnaires, including power of food scale [26] and food craving inventory. Therefore, further studies considering these limitations are recommended to assess food craving in different cultures and to assess food craving along with food intake to finding out that whether and to what extent food craving can affect food intake in people.

What is already known on this subject?

Food craving is associated with food intake and obesity. The type and intensity of food craving are much depended on food culture and may be different between communities. In addition, few studies showed that gender may affect food craving.

What does this study add?

For the first time, food craving inventory was evaluated in an Iranian population. Obese individuals experienced more food craving than normal weight subjects. In addition, this study provide further evidence in favor of sex differences in food craving.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that food craving would give rise to obesity. In addition, we observed sex differences in food craving, which may highlight documented sex differences in obesity prevalence. Regarding obesity as one of the greatest and most preventable global threats and food craving as the main reason of diet programs failure, application of FCI may be useful in understanding the complex etiology of obesity and improving weight loss programs and weight maintenance. The psychometric properties of the FCI-P were confirmed. It can be used to identify food craving behavior in Iranian populations. Women had higher scores in food craving compared to men. Therefore, food craving would be considered as a reason for higher prevalence of obesity in women.

References

Díez J, Bilal U, Cebrecos A, Buczynski A, Lawrence RS, Glass T et al (2016) Understanding differences in the local food environment across countries: a case study in Madrid (Spain) and Baltimore (USA). Prev Med 89:237–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.013

Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, Justice AE, Pers TH, Day FR et al (2015) Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 518:197–206. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14177

Perry CD, Degeneffe D, Davey C, Kollannoor-Samuel G, Reicks M (2016) Weight gain prevention among midlife women: a randomized controlled trial to address needs related to the physical and social environment. Int J Environ Res Public Health 13:530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13060530

Davis C, Carter JC (2009) Compulsive overeating as an addiction disorder. A review of theory and evidence. Appetite 53:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.018

Meule A, Hermann T, Kübler A (2015) Food addiction in overweight and obese adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Europ Eating Dis Rev 23:193–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2355

Pedram P, Wadden D, Amini P, Gulliver W, Randell E, Cahill F et al (2013) Food addiction: its prevalence and significant association with obesity in the general population. PLoS ONE 8:e74832. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074832

Finlayson G (2017) Food addiction and obesity: unnecessary medicalization of hedonic overeating. Nat Rev Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2017.61

Schulte EM, Avena NM, Gearhardt AN (2015) Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load. PLoS ONE 10:e0117959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117959

Apolzan JW, Myers CA, Champagne CM, Beyl RA, Raynor HA, Anton SA et al (2017) Frequency of consuming foods predicts changes in cravings for those foods during weight loss: the POUNDS lost study. Obesity. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21895

Meule A, Richard A, Platte P (2017) Food cravings prospectively predict decreases in perceived self-regulatory success in dieting. Eat Behav 24:34–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.11.007

Hill J, Heaton-Brown L (1994) The experience of food craving: a prospective investigation in healthy women. J Psychosom Res 38:801–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90068-X

Lafay L, Thomas F, Mennen L, Charles MA, Eschwege E, Borys JM (2001) Gender differences in the relation between food cravings and mood in an adult community: results from the Fleurbaix Laventie Ville Sante study. Int J Eat Disord 29:195–204. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(200103)29:2<195:AID-EAT1009>3.0.CO;2-N

Roefs A, Boh B, Spanakis G, Nederkoorn C, Lemmens LHJM, Jansen A (2019) “Food craving in daily life: comparison of overweight and normal-weight participants with ecological momentary assessment. J Hum Nutr Dietetics 32(6):765–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12693

Franken IH, Muris P (2005) Individual differences in reward sensitivity are related to food craving and relative body weight in healthy women. Appetite 45:198–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2005.04.004

Chao A, Grilo CM, White MA, Sinha R (2014) Food cravings, food intake, and weight status in a community-based sample. Eat Behav 15:478–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.06.003

Garawi F, Devries K, Thorogood N, Uauy R (2014) Global differences between women and men in the prevalence of obesity: is there an association with gender inequality? Eur J Clin Nutr 68:1101–1106. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2014.86

Spahlholz J, Baer N, König HH, Riedel-Heller S, Luck-Sikorski C (2016) Obesity and discrimination–a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Obesity Rev 17:43–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12343

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR (2010) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 303:235–241. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2014

Hallam J, Boswell RG, DeVito EE, Kober H (2016) Focus: sex and gender health: gender-related differences in food craving and obesity. Yale J Biol Med 89:161

Komatsu S (2008) Rice and sushi cravings: a preliminary study of food craving among Japanese females. Appetite 50:353–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.08.012

Nicholls W, Hulbert-Williams L (2013) British English translation of the food craving inventory (FCI-UK). Appetite 67:37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2013.03.010

E. Tarragon, J. Stein, and J. Meyer (2017) Psychometric properties of the german translated version and adaptation of the food craving inventory. Front Psychol 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00736

Massey A, Hill AJ (2012) Dieting and food craving. A descriptive, quasi-prospective study. Appetite 58:781–785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.01.020

Hill AJ (2007) The psychology of food craving. Proc Nutr Soc 66:277–285. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665107005502

Parker S, Kamel N, Zellner D (2003) Food craving patterns in Egypt: comparisons with North America and Spain. Appetite 40:193–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(02)00160-5

Aliasghari F, Jafarabadi MA, Yaghin NL, Mahdavi R (2018) Psychometric properties of power of food scale in Iranian adult population: gender-related differences in hedonic hunger. Eating and weight disorders-studies on Anorexia. Bulimia Obesity:1–9. Doi: 10.1007/s40519–018–0549–3

Moghaddam MB, Aghdam FB, Jafarabadi MA, Allahverdipour H, Nikookheslat SD, Safarpour S (2012) The Iranian version of international physical activity questionnaire (IPAQ) in Iran: content and construct validity, factor structure, internal consistency and stability. World Appl Sci 18:1073–1080. https://doi.org/10.5829/idosi.wasj.2012.18.08.754

Mostafavi S-A, Akhondzadeh S, Mohammadi MR, Eshraghian MR, Hosseini S, Chamari M et al (2017) The reliability and validity of the persian version of three-factor eating questionnaire-R18 (TFEQ-R18) in overweight and obese females. Iranian J Psychiatry 12:100 PMC 5483235

Committee IR (2005) Guidelines for data processing and analysis of the international physical activity questionnaire (ipaq)-short and long forms. http://www.ipaq.ki.se/scoring.pdf. Accessed 2 Jan 2020.

White MA, Whisenhunt BL, Williamson DA, Greenway FL, Netemeyer RG (2002) Development and validation of the food-craving inventory. Obesity 10:107–114. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2002.17

Guillemin F, Bombardier C, Beaton D (1993) Cross-cultural adaptation of health-related quality of life measures: literature review and proposed guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol 46:1417–1432. https://doi.org/10.1016/0895-4356(93)90142-N

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88:588. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Tinsley HE, Brown SD (2000) Handbook of applied multivariate statistics and mathematical modeling. Academic Press, Cambridge

Rodin J, Mancuso J, Granger J, Nelbach E (1991) Food cravings in relation to body mass index, restraint and estradiol levels: a repeated measures study in healthy women. Appetite 17:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(91)90020-S

Chou C-P, Bentler PM (1990) Model modification in covariance structure modeling: a comparison among likelihood ratio, lagrange multiplier, and Wald tests. Multivar Behav Res 25:115–136. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr2501_13

Kline RB (2015) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications, New York

De Medeiros ACQ, Pedrosa LDFC, Yamamoto ME (2017) Food cravings among Brazilian population. Appetite 108:212–218

I Jáuregui Lobera, P Bolaños, R Carbonero, E Valero Blanco (2010) Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of food craving inventory (FCI-SP). Nutrición Hospitalaria 25 https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2012.687667

Hormes JM, Niemiec MA (2017) Does culture create craving? Evidence from the case of menstrual chocolate craving. PLoS ONE 12:e0181445. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0181445

Akhoundan M, Shadman Z, Jandaghi P, Aboeerad M, Larijani B, Jamshidi Z et al (2016) The association of bread and rice with metabolic factors in type 2 diabetic patients. PLoS ONE 11:e0167921. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167921

Navadeh S, Sajadi L, Mirzazadeh A, Asgari F, Haghazali M (2011) Housewives’ obesity determinant factors in iran; national survey-stepwise approach to surveillance. Iranian J Publ Health 40:87 PMCID: PMC3481779

Golozar A, Khalili D, Etemadi A, Poustchi H, Fazeltabar A, Hosseini F et al (2017) White rice intake and incidence of type-2 diabetes: analysis of two prospective cohort studies from Iran. BMC Public Health 17:133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3999-4

Boswell RG, Kober H (2016) Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: a meta-analytic review. Obesity Rev 17:59–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12354

Hill AJ, Weaver CF, Blundell JE (1991) Food craving, dietary restraint and mood. Appetite 17:187–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0195-6663(91)90021-J

Martin CK, O’Neil PM, Tollefson G, Greenway FL, White MA (2008) The association between food cravings and consumption of specific foods in a laboratory taste test. Appetite 51:324–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.03.002

Gilhooly C, Das S, Golden J, McCrory M, Dallal G, Saltzman E et al (2007) Food cravings and energy regulation: the characteristics of craved foods and their relationship with eating behaviors and weight change during 6 months of dietary energy restriction. Int J Obesity 31:1849–1858. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803672

Cushing CC, Benoit SC, Peugh JL, Reiter-Purtill J, Inge TH, Zeller MH (2014) Longitudinal trends in hedonic hunger after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents. Surg Obesity Related Dis 10:125–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2013.05.009

Demos KE, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM (2012) Individual differences in nucleus accumbens activity to food and sexual images predict weight gain and sexual behavior. J Neurosci 32:5549–5552. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5958-11.2012

C. L. Carpenter, A. M. Wong, Z. Li, E. P. Noble, and D. Heber (2013) Association of dopamine D2 receptor and leptin receptor genes with clinically severe obesity. Obesity 21. DOI: 10.1002/oby.20202

Joyner MA, Gearhardt AN, White MA (2015) Food craving as a mediator between addictive-like eating and problematic eating outcomes. Eat Behav 19:98–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.07.005

Crowley N, Madan A, Wedin S, Correll JA, Delustro LM, Borckardt JJ et al (2014) Food cravings among bariatric surgery candidates. Eating Weight Dis-Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity 19:371–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-013-0095-y

Cushing CC, Peugh JL, Brode CS, Inge TH, Benoit SC, Zeller MH (2015) Longitudinal trends in food cravings following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in an adolescent sample. Surg Obesity Related Dis 11:14–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2014.05.035

Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, Carter JC, Kaplan AS, Kennedy JL (2011) Evidence that ‘food addiction’is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite 57:711–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.017

Pepino MY, Stein RI, Eagon JC, Klein S (2014) Bariatric surgery-induced weight loss causes remission of food addiction in extreme obesity. Obesity 22:1792–1798. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20797

Pelchat ML, Johnson A, Chan R, Valdez J, Ragland JD (2004) Images of desire: food-craving activation during fMRI. Neuroimage 23:1486–1493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.08.023

Meule A, Kübler A (2012) Food cravings in food addiction: the distinct role of positive reinforcement. Eat Behav 13:252–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.02.001

Wang G-J, Volkow ND, Logan J, Pappas NR, Wong CT, Zhu W et al (2001) Brain dopamine and obesity. The Lancet 357:354–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03643-6

Volkow ND, Wang G-J, Telang F, Fowler JS, Thanos PK, Logan J et al (2008) Low dopamine striatal D2 receptors are associated with prefrontal metabolism in obese subjects: possible contributing factors. Neuroimage 42:1537–1543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.06.002

de Weijer BA, van de Giessen E, Janssen I, Berends FJ, van de Laar A, Ackermans MT et al (2014) Striatal dopamine receptor binding in morbidly obese women before and after gastric bypass surgery and its relationship with insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia 57:1078–1080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-014-3178-z

Volkow N, Wang G, Fowler J, Tomasi D, Baler R (2011) Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction, In: Brain imaging in behavioral neuroscience, ed: Springer, pp 1–24. DOI: 10.1007/7854_2011_169

Hormes JM, Timko CA (2011) All cravings are not created equal. Correlates of menstrual versus non-cyclic chocolate craving. Appetite 57:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2011.03.008

Kiefer I, Rathmanner T, Kunze M (2005) Eating and dieting differences in men and women. J Men's Health Gender 2:194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmhg.2005.04.010

Cepeda-Benito A, Fernandez MC, Moreno S (2003) Relationship of gender and eating disorder symptoms to reported cravings for food: construct validation of state and trait craving questionnaires in Spanish. Appetite 40:47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(02)00145-9

Imperatori C, Innamorati M, Tamburello S, Continisio M, Contardi A, Tamburello A et al (2013) Gender differences in food craving among overweight and obese patients attending low energy diet therapy: a matched case–control study. Eating Weight Dis-Stud Anorexia Bulimia Obesity 18:297–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0195-6663(02)00145-9

Chao AM, Grilo CM, Sinha R (2016) Food cravings, binge eating, and eating disorder psychopathology: exploring the moderating roles of gender and race. Eat Behav 21:41–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.007

Ward MA, Carlsson CM, Trivedi MA, Sager MA, Johnson SC (2005) The effect of body mass index on global brain volume in middle-aged adults: a cross sectional study. BMC Neurol 5:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-5-23

Burton P, Smit HJ, Lightowler HJ (2007) The influence of restrained and external eating patterns on overeating. Appetite 49:191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2007.01.007

Macedo DM, Diez-Garcia RW (2014) Sweet craving and ghrelin and leptin levels in women during stress. Appetite 80:264–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.05.031

Lim D (2015) But why do women like sweets? Discourses on women's sweets consumption in contemporary south korea.

Lemon CH (2015) Perceptual and neural responses to sweet taste in humans and rodents. Chemosens Percept 8:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12078-015-9177-8

Lampuré A, Schlich P, Deglaire A, Castetbon K, Péneau S, Hercberg S et al (2015) Sociodemographic, psychological, and lifestyle characteristics are associated with a liking for salty and sweet tastes in French adults. J Nutr 145:587–594. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.201269

Preedy VR, Watson RR, Martin CR (2011) Handbook of behavior, food and nutrition, Springer Science & Business Media

Yen J-Y, Chang S-J, Ko C-H, Yen C-F, Chen C-S, Yeh Y-C et al (2010) The high-sweet-fat food craving among women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Emotional response, implicit attitude and rewards sensitivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35:1203–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.02.006

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their time, patience, and cooperation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Vice Chancellor for Research Affairs [grant number: 5/D/996710].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

Authors declared no conflicts of interests.

Ethical approval

The protocol of the study was approved by the university ethic committee [IR.TBZMED.REC.1395.1013]. All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the committee and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 as revised in 2000.

Informed consent

The participants signed an informed consent before the commencement of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Food and addiction

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aliasghari, F., Jafarabadi, M.A., Yaghin, N.L. et al. The food craving inventory in an Iranian population: post-hoc validation and individual differences. Eat Weight Disord 26, 1529–1539 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00976-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00976-7